Abstract

Zinc is an essential microelement to sustain all forms of life. However, excess of zinc is toxic, therefore dedicated import, export and storage proteins for tight regulation of the zinc concentration have evolved. In Enterobacteriaceae, several membrane transporters are involved in zinc homeostasis and linked to virulence. ZntB has been proposed to play a role in the export of zinc, but the transport mechanism of ZntB is poorly understood and based only on experimental characterization of its distant homologue CorA magnesium channel. Here, we report the cryo-electron microscopy structure of full-length ZntB from Escherichia coli together with the results of isothermal titration calorimetry, and radio-ligand uptake and fluorescent transport assays on ZntB reconstituted into liposomes. Our results show that ZntB mediates Zn2+ uptake, stimulated by a pH gradient across the membrane, using a transport mechanism that does not resemble the one proposed for homologous CorA channels.

The bacterial zinc transporter ZntB is important for maintaining zinc homeostasis and is mechanistically not well understood. Here, the authors present the cryo-EM structure of ZntB at 4.2 Å resolution, perform transport assays and propose a model for its Zn2+ transport mechanism.

Introduction

Zinc is one of the few ‘essential-but-also-toxic’ divalent cations required for the cell and is an important ‘token coin’ in host:pathogen interactions1: whenever host organisms try to sequester all available zinc at the host:pathogen interface to reduce the virulence of invading bacteria2, the latter employ highly specific uptake systems to scavenge zinc3. Conversely, if the zinc concentration is elevated in hosts to oppress pathogens4, the latter regulate their intracellular zinc concentration by scaling up the export of zinc3. Due to this ambidexterity, the tight regulation of zinc homeostasis is crucial. Different bacteria cope with this task in a variety of ways—for example, by storage of zinc by metallothioneins as in cyanobacteria5, by assembly of redundant importers as in Cupriavidus metallidurans 6 or via a controlled shunt of zinc export–import as in Escherichia coli, where zinc–iron permeases (ZIPs) family transporter ZupT7 and the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter ZnuABC8,9 are recruited for import, and P-type ATPase ZntA10 and cation-diffusion facilitator YiiP11 for export of zinc (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, the zinc transporter ZntB, which belongs to the CorA metal ion transporter (MIT) family is widespread in Enterobacteriaceae12,13. There is controversy over the question whether ZntB is an exporter12 or importer6. Furthermore, mechanistic insight is lacking because crystal structures are available of only cytoplasmic parts of ZntB14,15, and scarce transport activity measurements have been performed only in whole cells. We have obtained the structure of full-length ZntB from E. coli and performed isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), radiolabelled zinc uptake and fluorescent transport experiments with ZntB reconstituted into liposomes. This study shows that ZntB mediates Zn2+ transport, which is stimulated by a pH gradient across the membrane. The comparison of the full-length structure of ZntB with previously resolved structures of ZntB soluble domains in different conditions (in the presence and absence of Zn2+) and structures of homologous CorA proteins, is indicative that ZntB and CorA proteins utilize different transport mechanisms.

Results

Structure of ZntB

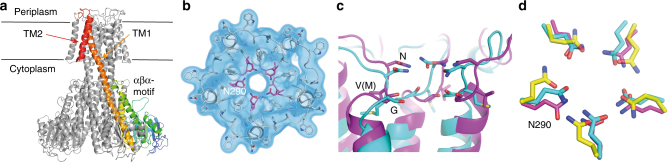

The apo structure of ZntB was obtained by single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) using n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DDM)-solubilized and purified E. coli ZntB (EcZntB) (pre-treated with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)) and resolved at an overall resolution of 4.2 Å (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3, Table 1). The structure of ZntB revealed a pentameric arrangement (Fig. 1a, b), similar to that reported for other members of the CorA family13,16,17 (Supplementary Fig. 4) even though CorA and ZntB share very little sequence identity (below 20%) (Supplementary Fig. 5). Each protomer of ZntB consists of a large N-terminal cytoplasmic domain folded into an αβα motif. A long α-helix protrudes from the cytoplasmic domain into the membrane (TM1) and is joined to a second transmembrane helix (TM2) (Fig. 1a) via the only periplasmic loop, which bears the signature motif GxN of the CorA MIT family13 (Fig. 1b, c). In the resolved structure of EcZntB, the cytoplasmic domain is very similar to the isolated domain of ZntB from Vibrio parahaemolyticus (Vp)14 (rmsd ~2.5 Å), but significantly different from the homologous domain of Salmonella typhimirium (St) ZntB15 (rmsd ~12 Å). Taking into account very high sequence conservation between EcZntB and StZntB of 92.6% (Supplementary Fig. 5), the structural difference is intriguing. This difference could be attributed to the two structures representing two different states in the transport cycle (discussed below). Analysis of the substrate translocation pore revealed a wider profile in ZntB than in the magnesium channels TmCorA and MjCorA (Supplementary Fig. 6). All three proteins have short extracellular loops between TM1 and TM2, where the family signature motif GxN that forms the selectivity filter (Fig. 1b, c) is located. Whereas in CorA proteins the signature motif has the sequence GMN, ZntBs show a Met to Val substitution, potentially having consequences for the substrate recognition, as in ZntB, the radius of the filter is ~4.5 vs 3.5–4.0 Å in CorAs (Fig. 1d).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

| Microscope | Titan KRIOS with K2-detector |

| Voltage | 300 kV |

| Pixel size (Å) | 1.43 |

| Micrographs collected (#) | 2655 |

| Refinement | |

| Particles (#) | 333,490 |

| Resolution (Å; at FSC = 0.143) | 4.2 |

| CC (model to map fit) | 0.81 (0.83) |

| RMS deviations | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.007 |

| Angles (°) | 1.152 |

| Chirality (°) | 0.065 |

| Planarity (°) | 0.008 |

| Validation | |

| Clash score | 12 |

| Favoured rotamers (%) | 98.77 |

| Ramachandran favoured (%) | 91.69 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 8.31 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0 |

Fig. 1.

The structure of the full-length ZntB. a Side view, four subunits of ZntB pentamer are coloured grey, and one is coloured rainbow from blue (N-terminus) to red (C-terminus); the position of the membrane is indicated, trans membrane helices 1 and 2 as well as αβα-motif are labelled. b Top view (from periplasm) onto ZntB—10 trans membrane helices are arranged cylindrically, with TM2 ring at the periphery. Experimental density is contoured in blue. The connecting loops provide residues for the selectivity filter (in magenta), further exemplified in (c) structural comparison of selectivity filters from EcZntB (magenta) and TmCorA (cyan), only three out five monomers are shown (d). The overlay of Asn rings (of GxN motif) from ZntB (magenta), TmCorA (cyan) and MjCorA (yellow). Note that ZntB forms a slightly wider entry point to the pore

Substrate selectivity of ZntB

One of the puzzling features of the CorA family is substrate selectivity. The geometry of the selectivity filter is thought to define the correct distances between (partially) hydrated cation and amino acid side chains of the filter, and hence recognition18,19. Intriguingly, although the hydrated radii of known transported substrates for the CorA family are very similar (2.10 Å, 2.09 Å, 2.10 Å, 2.07 Å for Zn2+ 20, Mg2+ 21, Co2+ 21,22 and Ni2+ 23, respectively) and all these cations have a similar octahedral arrangement of six water molecules in their first hydration shell in aqueous solution; different subfamilies have distinct substrate specificities. It has been proposed that this selectivity might be based on the rigidity of ion solvation shells and rates of water exchange18.

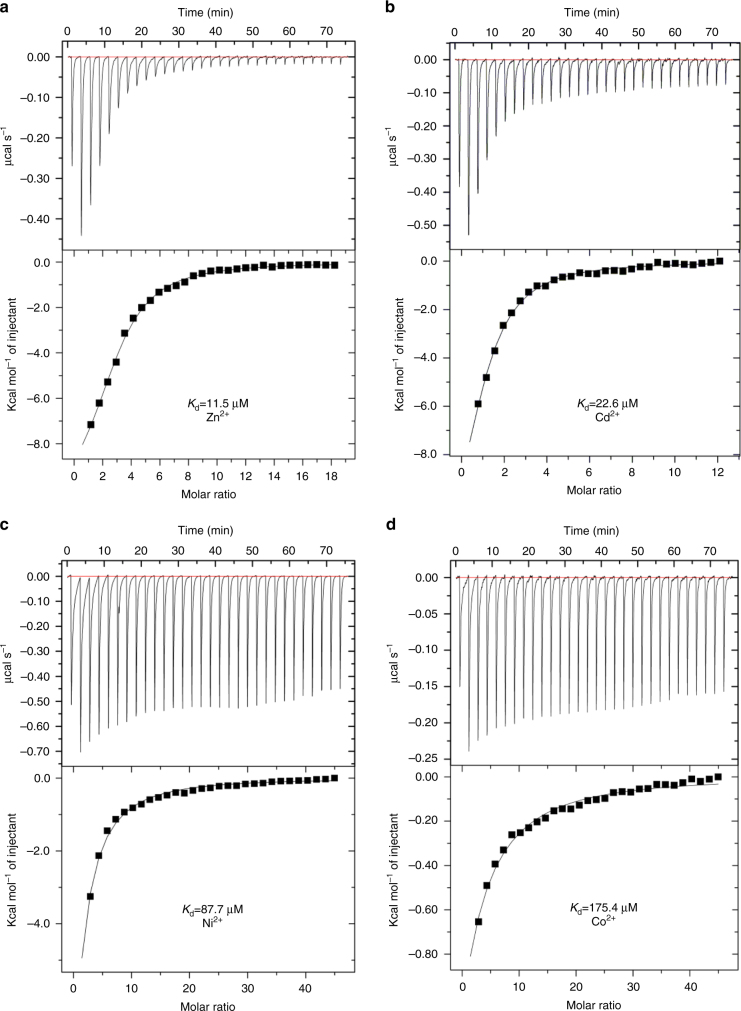

To characterize the specificity, we performed ITC experiments and fluorescent transport assays. ITC experiments revealed binding of Zn2+, Cd2+, Ni2+ and Co2+ to ZntB, with K d values of 11.5, 22.6, 87.7 and 175.4 µM, respectively, in 1:1 stoichiometry (Fig. 2). No binding of Mn2+, Mg2+ and Cu2+ was detected. The ability of ZntB proteins to select Zn2+ over Mg2+, and conversely the ability of CorA proteins to select Mg2+ over Zn2+, may be explained by different sizes of the pore—the substitution of a single amino acid in the signature motif (see above) might be enough. However, Co2+ and Ni2+ appear to be substrates of both ZntB and CorA24,25, thus the precise determinants of selectivity are still elusive. We additionally tested the transport of the cations by ZntB reconstituted into the liposomes, and found that the ions that bind to the protein in ITC assay are also transported (see below).

Fig. 2.

ITC profiles of substrate binding to ZntB of (a) Zn2+ (b) Cd2+ (c) Ni2+ (d) Co2+

Zinc transport by ZntB is stimulated by pH gradient

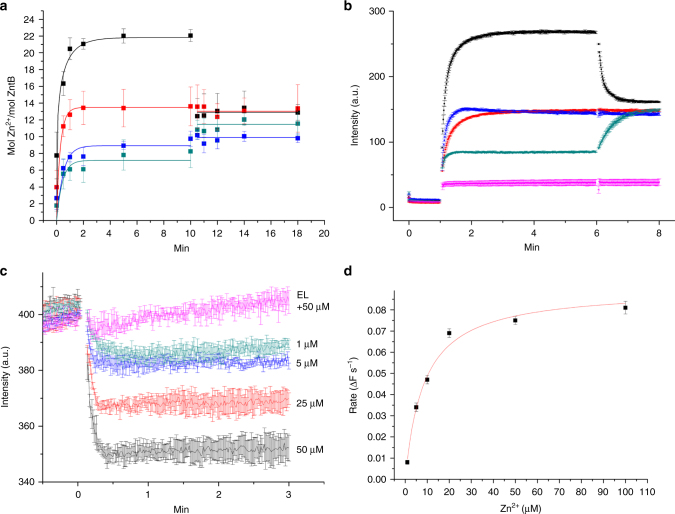

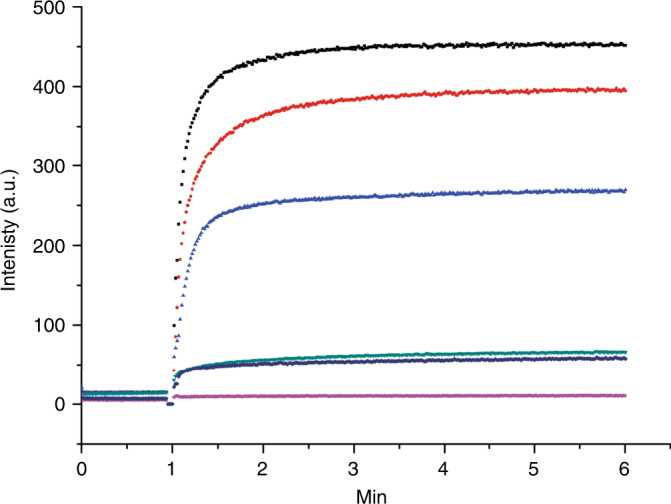

To characterize the mode of transport, we performed the 65Zn2+ uptake assays with purified ZntB reconstituted into liposomes. Transport was measured using either equal pH on the inside and outside of the liposomes, or using pH gradients. Zn2+ was taken up by the liposomes containing ZntB, and uptake was enhanced by a pH gradient with the lumen of the liposomes more basic than the outside. In contrast, uptake was suppressed in the presence of a reverse pH gradient. These experiments suggest that zinc transport is driven by the pH gradient. Consistently, addition of the proton ionophore FCCP at a time point when the uptake had reached a plateau led to efflux of the accumulated 65Zn2+ in case of a pH gradient that was basic inside (Fig. 3a), and addition of FCCP to liposomes with the opposite pH gradient stimulated additional uptake. FCCP did not affect the Zn2+ accumulation in the absence of a pH gradient (Fig. 3a). These results were confirmed by performing the transport assays with the specific zinc reporting dye fluozin-126, encapsulated into liposomes. The fluorescence signal increased upon Zn2+ transport into the liposomes and FCCP had a similar effect as in uptake assays with radiolabelled Zn2+ (Fig. 3b). The observed stimulation of Zn2+ uptake by an inward pH gradient suggests a mechanism in which protons are co-transported with Zn2+. We directly measured Zn2+-dependent proton transport using pH-sensitive fluorophore 9-amino-6-chloro-2-methoxyacridine (ACMA) (Fig. 3c) with proteoliposomes that had equal pH in the lumen and exterior. Zn2+ uptake into these proteoliposomes was accompanied by generation of a pH gradient, consistent with coupled H+-Zn2+ transport mechanism. A Na+ gradient instead of a proton gradient did not stimulate transport (Supplementary Fig. 7). These experiments show that Zn2+ transport is stimulated by a proton gradient across the membrane. Finally, the transport of Zn2+ saturated with increasing Zn2+ concentrations with a K M of ~7.5 µM (Fig. 3d), again indicative of a transporter mechanism.

Fig. 3.

Radioactive and fluorescent transport assays (a) 65Zn2+ uptake via ZntB reconstituted in liposomes under different conditions (colour-coded: black—inward pH flux (7.5 in/6.5 out); green—outward pH flux (6.5 in/7.5 out); red and blue—no pH flux at 6.5 and 7.5 pH, respectively). Ionophore FCCP was added at the time point of 10 min. Note the opposite effect of FCCP on direct and reverse pH gradient. Error bars represent s.e.m. from more than three technical replicates of independent batches of proteoliposomes. b Changes in fluorescent signal by the reporter dye FluoZin-1 during uptake of Zn2+ (added at 1 min time point) via ZntB reconstituted in liposomes under different conditions (colour-coding as in a, additionally the signal from empty liposomes in magenta). FCCP was added at the time point of 6 min. Error bars represent s.e.m. from more than three technical replicates of independent batches of proteoliposomes. c Zn2+-dependent transport of H+ via ZntB. Quenching of the pH-dependent fluorophore ACMA at different Zn2+ concentrations is shown by unique colours. d Rate of transport dependence on Zn2+ concentration. The solid line represents the fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation with a K M of ~7.5 µM (based on FluoZin-1 experiments)

To complement the ITC experiments on substrate binding (see above), we tested whether Ni2+, Co2+, Cd2+ could be transported by ZntB reconstituted into the liposomes using the fluozin-1 dye, and observed comparable levels of transport for Ni2+ and Cd2+, but not for Co2+. The failure to detect transport of Co2+ is likely caused by lower sensitivity of the dye for this cation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Transport of different cations by ZntB. Transport of different cations (added at 1 min and colour-coded: black—20 µM Zn2+, red—20 µM Cd2+, blue—100 µM Ni2+, green—200 µM Co2+, dark blue—empty liposomes with 20 µM Zn2+, magenta—empty liposomes with 200 µM Co2+) assayed by the fluorophore Fluozine-1 trapped inside the proteoliposomes

Discussion

ZntB is a distant homologue of CorA proteins, which are well-characterized magnesium (and cobalt) channels13,16,17,27. Based on whole-cell transport experiments on ZntB12 and structures of soluble domains14,15, it has been proposed that CorA superfamily contains both channels (CorA) and transporters (ZntB), the latter possibly using a different transport mechanism12. A recently reported cryo-EM structure of TmCorA in Mg2+-free conditions, obtained upon EDTA treatment, revealed an unprecedented asymmetry of the pentamer28. It was concluded that CorA proteins might use a transport mechanism that involves a partial loss of the fivefold symmetry in the open state28–30 to create a pore wide enough for the transport of partially hydrated magnesium. Our work on ZntB shows that the mechanism cannot be extrapolated to other members of the family, because even after an extensive treatment with EDTA ZntB maintained its symmetrical pentameric state (Supplementary Fig. 8). There are several possible explanations for the differences between CorA and ZntB. First, the structural differences are genuine, and related to mechanistic differences between CorA and ZntB. Second, ZntB can also form a collapsed state, but under different conditions than CorA (perhaps in the membrane). Third, the observed symmetry-collapsed state of CorA is an artefact, possibly induced by the Mg2+-free conditions that were used to obtain the structure. Such conditions are probably never encountered by the protein under physiological conditions, as the intracellular concentration of free Mg2+ is estimated to be around 0.5–1mM31. Also, other intracellular divalent and monovalent cations were shown to bind to TmCorA30. Therefore, it is possible that the observed symmetry-collapsed structure is not part of the mechanism of channel opening. In contrast to stringent removal of Mg2+ from CorA channels, the depletion of Zn2+ from ZntB is likely to be physiologically relevant because intracellular concentrations of free Zn2+ are extremely low (i.e., in the pM–fM range32,33). Therefore the symmetrical structure of ZntB may better represent the apo state than the asymmetrical structure of CorA.

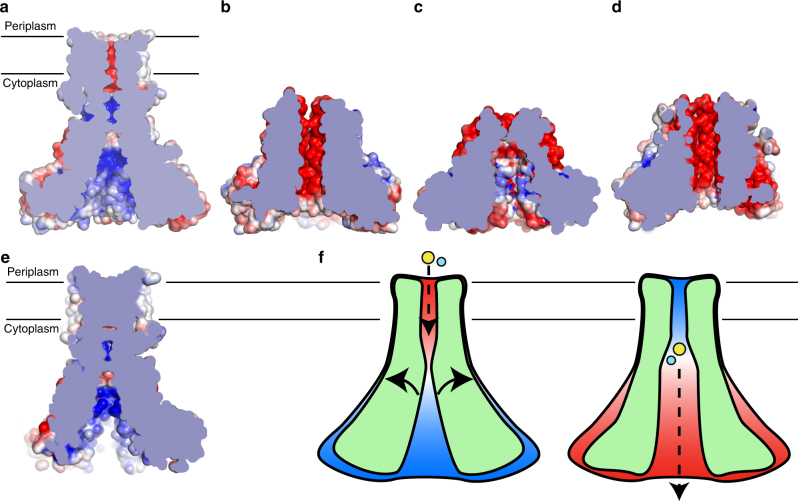

To understand the mechanism of transport used by ZntB, the structures of the different states are essential. A comparison of our full-length structure with the structure of the soluble domain of StZntB provides a first indication of the movements that may occur within the symmetrical scaffold to provide a pathway for the transported zinc (Fig. 5). Whereas our structure was obtained in the absence of Zn2+, StZntB was crystallized in the presence of Zn2+. Calculation of the surface potentials revealed dramatic differences between full-length EcZntB and soluble StZntB (Fig. 5a, b). The cytoplasmic domain of full length EcZntB has a strong positive electrostatic surface potential (resembling VpZntB (Fig. 5c)), whereas the potential in the isolated domain of StZntB is negative15. Threading of the EcZntB sequence in the StZntB produced a similar result of more negative surface potential (Fig. 5d) and the reverse threading (StZntB sequence in EcZntB model) produced a positive surface potential (Fig. 5e). Furthermore, the shape of the internal pore between two forms is different (Fig. 5) possibly resembling two conformational states. The charge inversion of the pore surface (Fig. 5f) between the two symmetrical states might be caused by helical rotation of TM1, which bears a patch of highly conserved basic and acidic residues on the adjacent faces of the helix.

Fig. 5.

Possible mechanism of Zn2+ transport by ZntB. a Calculated electrostatic potential (±5 kT e−1) of ZntB (cross-section of the pore is shown) (b) same for Zn2+-bound soluble domain of StZntB and (c) Zn2+-free soluble domain of VpZntB. d Phyre2-based model of putative Zn2+-bound EcZntB using StZntB as a template (pdb id 3NWI). e Phyre2-based model of full-length apo StZntB using EcZntB as a template. f Putative mechanism of Zn2+ transport via ZntB. ZntB cross-section is shown schematically; Zn2+ and H+ are shown as yellow and cyan spheres, respectively; arrows indicate possible movements of trans membrane helix 1, which are possibly caused by Zn2+ and/or H+ binding, eventually leading to the change in electrostatic potential (from positive (blue) to negative (red)) within the pore that stimulates ion advancement through it

It has been debated whether ZntB is primarily used for import or export. Whole-cell assays have indicated that ZntB is a Zn2+ and Cd2+ exporter12. This conclusion was based on experiments using a knockout strain, from which it was assumed that all zinc transporters had been deleted. However, recent studies revealed that additional transporters, such as PitA6, HoxN, ActP34 and the STM0353 gene product (homologous to CadA35), might contribute significantly to zinc transport. Nevertheless, these results showed that ZntB at least affected the transport of Zn2+ and Cd2+. Interestingly, the analysis of regulation of ZntB expression in C. metallidurans revealed that it was downregulated in the presence of high concentrations of Zn2+, Cd2+ and Cu2+6, which suggests that it is an importer, rather than an exporter. Additionally the expression of homologous ZntB from Agrobacterium tumefaciens was not induced by treatments with Zn2+ in a range from 100 to 750 µM36. Our experiments show that ZntB most likely mediates Zn2+/H+ co-transport, and thus indicate that ZntB is an importer for zinc. This indeed confirms that the same fold within CorA superfamily can be used either as a channel (CorA) or a transporter (ZntB).

In conclusion, we have resolved the full-length structure of a ZntB transporter, a member of the CorA MIT family. We have performed ligand binding and ligand-transport assays that unambiguously show that ZntB is involved in zinc transport. By combining all available data from us and other groups, we conclude that ZntB is a zinc importer that is driven by a proton gradient. Its transport mechanism appears distinct from that of CorA Mg2+ channels. Unlike CorA, ZntB does not collapse into a highly asymmetrical state upon depletion of divalent cations. The elucidation of different conformational states of ZntB will be essential to describe its transport mechanism in greater detail.

Methods

Protein expression and membrane vesicle preparation

Expression of ZntB was performed in a 5-l flask containing 2 l of LB medium (10 g l−1 Bacto trypton, 5 g l−1 Bacto yeast extract, 10 g l−1 NaCl), supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin and 34 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol. The E. coli BL-21(DE3) cells with pNIC_BSA4_ZntB (pNIC28-Bsa4 was a gift from Opher Gileadi (Addgene plasmid #26103)37) were grown at 37 °C, 200 r.p.m. to an OD600 of 0.8, with an induction by addition of 0.1 mM IPTG. After 3 h of expression, the cells were collected by centrifugation (15 min, 7446×g, 4 °C), washed in buffer A (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0) and resuspended in the buffer B (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol). Straight away, membrane vesicles were prepared or alternatively the resuspended cells were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

MgSO4 of 1 mM and 50–100 μg ml−1 DNase were added to the cells before membrane vesicle preparation. Next, the cells were disrupted and lysed by high-pressure (Constant Cell Disruption System Ltd., UK, two passages at 25 kPsi, 5 °C) cell debris was removed by low-speed centrifugation (30 min, 12,074×g, 4 °C), and membrane vesicles were collected by ultracentrifugation (120 min, 193,727×g, 4 °C). After that, the collected membrane vesicles were resuspended in buffer C (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 15% glycerol) to a final volume of 5 ml per 1 liter of cell culture. Subsequently, aliquoted membrane vesicles were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C. Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad) was used to determine the total protein concentration in the prepared membrane vesicles.

Protein purification

Prepared membrane vesicles were rapidly thawed and immediately solubilized in buffer D (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 1% (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DDM, Anatrace)) at 4 °C for 1 h, while gently rocking. To remove unsolubilized material the centrifugation step (30 min, 442,907×g, 4 °C) was applied. After that, the supernatant was incubated for 1 h with Ni2+-sepharose resin (column volume of 0.5 ml) at 4 °C, pre-equilibrated with 20 CV of buffer E (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM imidazole, 0.03% DDM). Next, the flow through was collected after the suspension had been poured into a 10-ml disposable column (Bio-Rad). The column material was washed with 10 ml of buffer E. ZntB was eluted in three fractions of buffer F (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, 0.03% (w/v) DDM) of 200, 750 and 500 µl, respectively. The second elution fraction was treated with 2 mM of EDTA to remove co-eluted Ni2+ ions and any residual zinc. Later on, the second elution fraction was subjected to size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 10/300 gel filtration column (GE-Healthcare), pre-equilibrated with buffer G (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 0.03% (w/v) DDM). Fractions containing purified were combined and used directly for proteoliposome reconstitution, or concentrated by the use of a Vivaspin 500 concentrating device with a molecular weight cutoff of 100 kDa (Sartorius stedim) to a final concentration of 3–6 mg ml−1 with or without additional 1 mM EDTA added when prepared for Cryo-EM.

Reconstitution into proteoliposomes

Reconstitution in proteoliposomes was performed as follows (please see ref. 38 for details): polar lipids of E. coli and egg phosphatidylcholine (in 3:1 (w/w) ratio) were dissolved in chloroform, then dried in a rotary evaporator and subsequently resuspended in buffer containing 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5 to the concentration of 20 mg ml−1. After three freeze-thaw cycles, large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) were obtained and stored in liquid nitrogen. To prepare proteoliposomes, LUVs were extruded through a 400-nm-diameter polycarbonate filter (Avestin, 11 passages). Obtained liposomes were diluted to 4 mg ml−1 in buffer H (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) or buffer I (50 mM HEPES, pH 6.5) and subsequently destabilized beyond R sat with Triton X-100. Purified ZntB was added to the liposomes at a weight ratio of 1:250 (protein/lipid), followed by detergent removal using Bio-beads (50 mg ml−1, four times after 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h and overnight incubation). Afterwards, proteoliposomes were collected by centrifugation (25 min, 285,775×g, 4 °C) and resuspended in buffer H or buffer I to a lipid concentration of 10 mg ml−1. Finally, after three freeze-thaw cycles, obtained proteoliposomes were stored in liquid nitrogen until subsequent experiments.

Radiolabelled 65Zn2+ transport assay

To use in the transport assay, proteoliposomes with desired pH were thawed and extruded through a 400-nm pore size polycarbonate filter (Avestin, nine passages). Subsequently, two active units of ProTev Plus (Promega) were added to the protein sample and incubated overnight. The proteoliposomes were diluted 10 times to a final volume of 2 ml in the same buffer. Following centrifugation step (25 min, 285,775×g, 4 °C), the proteoliposomes were resuspended in buffer H or I to a final concentration of 0.5 μg ul−1 ZntB. For each time point in the transport assays, a reaction volume of 200 μl of buffer (with desired pH) with 22 μM of 65ZnCl2 added, was incubated at 30 °C while being stirred. Transport was initiated by adding 1 μg of ZntB, previously reconstituted in proteoliposomes. Stop buffer of 2 ml (ice-cold outside buffer) was added at the indicated time point, and the reaction was rapidly filtered over a BA-85 nitrocellulose filter. After the filter was washed with another 2 ml of stop buffer, the levels of radioactivity were determined using a Packard Cobra II 5010 Gamma counter.

Fluorescent transport assays

Zinc transport was measured with the Zn2+-sensitive fluorophore FluoZin-1 (ThermoFisher, USA). To avoid bleaching of the fluorophore, the sample was shielded from the direct light as much as possible. FluoZin-1 (stock concentration 3 mM in H2O) was added to a final concentration of 5 μM to the proteoliposomes with desired pH. FluoZin-1 encapsulation was performed by three freeze–thaw cycles and subsequent extrusion through 0.4-µm polycarbonate filters. Extravesicular dye was removed from ~500 μl of liposome suspension by size exclusion chromatography on a 2 ml Sephadex G-75 column equilibrated with buffer H or I. Proteoliposomes were collected by ultracentrifugation (25 min, 285,775×g, 4 °C), and the supernatant was removed. Proteoliposomes were resuspended with 10 μl buffer H or I per 2.5 mg of proteoliposomes (protein to lipid ratio 1:250). Transport assays with or without proton gradient were initiated by the addition of 10 mM stock solution of zinc acetate to the desired final concentration. For each measurement, 0.3 mg of proteoliposomes (protein to lipid ratio 1:250) was diluted in 1 ml of desired buffer. A fluorescence time course was measured in a 1 ml cuvette with a stirrer using an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm. Experiments with empty liposomes were performed in parallel as controls. Initial transport rates (ΔF s−1) were calculated by performing a linear regression on the transport data between 1 and 10 s after addition of zinc acetate. The resulting data was fitted to a Michaelis–Menten equation. All measurements were at least triplicated.

For H+ transport assays, the lumenal buffer of the proteoliposomes was exchanged for buffer J (5 mM HEPES pH 6.7) by resuspension of the liposomes in this buffer followed by three freeze-thaw cycles and extrusion through 0.4-μm polycarbonate filters. Proteoliposomes were collected by ultracentrifugation (25 min, 285,775×g, 4 °C), and the supernatant was removed. Proteoliposomes were resuspended with 10 μl buffer J per 2.5 mg of proteoliposomes (protein to lipid ratio 1:250). For each measurement, 0.3 mg of proteoliposomes was diluted in 1 ml of buffer K (5 mM HEPES, pH 6.7, 150 nM ACMA). A fluorescence time course was measured in a 1 ml cuvette with a stirrer using an excitation wavelength of 419 nm and an emission wavelength of 483 nm; zinc was added after 3 min of equilibration time. Experiments with empty liposomes were performed in parallel as controls. All measurements were triplicated.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

ITC200 instrument (MicroCal) was used to perform all ITC experiments. The thermally equilibrated ITC cell was filled with 280 μl of ZntB in buffer G (10–15 µM) and studied substrates (in the same buffer) were titrated into the cell. Temperature was fixed at 25 °C. Analysis of data was performed using the origin-based software provided by MicroCal.

Single particle cryo-electron microscopy

The purified ZntB sample was adjusted to a final concentration of ~10 mg ml−1. Aliquots of 3 μl were applied to a freshly glow-discharged holey carbon grids (Quantifoil Au R1.2/1.3, 300 mesh), excess liquid was blotted for 4–5 s using a FEI Vitrobot Mark IV and the sample was plunge frozen in liquid ethane at a temperature of approximately 100 K. TEM grids were transferred into a Titan Krios 300 keV microscope (FEI, Netherlands), equipped with a K2 direct-electron detector. Zero-loss images were recorded semi-automatically, using the UCSF Image4 script39. The GIF-quantum energy filter was adjusted to a slit width of 20 eV. Images were collected at a nominal magnification of ×81,000 (yielding a pixel size of 1.43 Å) and a defocus range of −1.5 to −3.0 μm. A total of 2655 movie images were collected with 24 frames dose-fractionated over 18 s, in super-resolution counting mode.

Beam-induced motion in the raw movie frames was corrected for using whole-frame motion correction with MOTIONCORR 1.040, followed by contrast transfer function (CTF) estimation using gctf41. All subsequent data processing steps were performed using the RELION 2.0 software suite42. References for template-based particle picking were obtained from two-dimensional (2D) classes obtained from manually picked particles from a subset of micrographs. The initial run of template-based algorithm picked 1 million particles from all 2655 images. To reduce the number of false-positive particle picks from the initial template-based particle picking, several rounds of 2D classification were applied to the full extracted data set, resulting in a subset of 333,490 particle projections. The resulting particles were submitted to three-dimensional auto-refinement, particle-based motion correction and damage-based weighting of individual frames43. An additional round of 2D classification was performed on these ‘polished’ particles to further discard false-positive or low-quality particles. The obtained map was used for manual model building in Coot44 using the previously published CorA structure (pdb id: 4I0U) as a reference model. Refinement was performed in Phenix45 with the final validation check in Molprobity46. The ‘Zn2+-bound’ model of EcZntB and ‘Zn2+-free’ model of StZntB were obtained by threading EcZntB sequence into StZntB model with the Phyre2 server47. Electrostatic potentials were calculated with APBS48 after the initial preparation of files at PDB2PQR server49. Images were prepared with the open source version of PyMol (https://sourceforge.net/projects/pymol/).

Data availability

Atomic coordinates and the corresponding electron microscopy density map are deposited in the Protein Data Bank and the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under accession number 5N9Y and EMD-3605, respectively. Other data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to M. Guskova for help with figures preparation. This research was supported by HFSP fellowship (LTF000087/2015-L) to C.G. and NWO Vidi grant 723.014.002 to A.G.

Author contributions

A.G. conceived the project. Expression, purification, ITC, radioactive zinc uptakes and transport assays were performed by A.S. Cryo-EM was carried out by C.G. and S.H.W.S. Model building and refinement was done by A.G. A.S., C.G., D.J.S., S.H.W.S. and A.G. analysed the data. A.G. and D.J.S. wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Cornelius Gati and Artem Stetsenko contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01483-7.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sjors H. W. Scheres, Email: scheres@mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk

Albert Guskov, Email: a.guskov@rug.nl.

References

- 1.Capdevila DA, Wang J, Giedroc DP. Bacterial strategies to maintain zinc metallostasis at the host-pathogen interface. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:20858–20868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.742023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kehl-Fie TE, Skaar EP. Nutritional immunity beyond iron: a role for manganese and zinc. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010;14:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blindauer CA. Advances in the molecular understanding of biological zinc transport. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:4544–4563. doi: 10.1039/C4CC10174J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ong C-LY, Gillen CM, Barnett TC, Walker MJ, McEwan AG. An antimicrobial role for zinc in innate immune defense against group A Streptococcus. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;209:1500–1508. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blindauer CA, et al. A metallothionein containing a zinc finger within a four-metal cluster protects a bacterium from zinc toxicity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:9593–9598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171120098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herzberg M, Bauer L, Kirsten A, Nies DH. Interplay between seven secondary metal uptake systems is required for full metal resistance of Cupriavidus metallidurans. Metallomics. 2016;8:313–326. doi: 10.1039/C5MT00295H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karlinsey JE, Maguire ME, Becker LA, Crouch M-LV, Fang FC. The phage shock protein PspA facilitates divalent metal transport and is required for virulence of Salmonella enterica sv. Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;78:669–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ammendola S, et al. High-affinity Zn2+ uptake system ZnuABC is required for bacterial zinc homeostasis in intracellular environments and contributes to the virulence of Salmonella enterica. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:5867–5876. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00559-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perry RD, Bobrov AG, Fetherston JD. The role of transition metal transporters for iron, zinc, manganese, and copper in the pathogenesis of Yersinia pestis. Metallomics. 2015;7:965–978. doi: 10.1039/C4MT00332B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang K, et al. Structure and mechanism of Zn2+−transporting P-type ATPases. Nature. 2014;514:518–522. doi: 10.1038/nature13618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu M, Fu D. Structure of the zinc transporter YiiP. Science. 2007;317:1746–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.1143748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worlock AJ, Smith RL. ZntB is a novel Zn2+ transporter in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:4369–4373. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.16.4369-4373.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Payandeh J, Pfoh R, Pai EF. The structure and regulation of magnesium selective ion channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1828:2778–2792. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan K, et al. Structure and electrostatic property of cytoplasmic domain of ZntB transporter. Protein Sci. 2009;18:2043–2052. doi: 10.1002/pro.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan Q, et al. X-ray crystallography and isothermal titration calorimetry studies of the Salmonella zinc transporter ZntB. Structure. 2011;19:700–710. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordin N, et al. Exploring the structure and function of Thermotoga maritima CorA reveals the mechanism of gating and ion selectivity in Co2+/Mg2+ transport. Biochem. J. 2013;451:365–374. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guskov A, et al. Structural insights into the mechanisms of Mg2+ uptake, transport, and gating by CorA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:18459–18464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210076109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guskov A, Eshaghi S. The mechanisms of Mg2+ and Co2+ transport by the CorA family of divalent cation transporters. Curr. Top. Membr. 2012;69:393–414. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394390-3.00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dudev T, Lim C. Importance of metal hydration on the selectivity of Mg2+ versus Ca2+in magnesium ion channels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:17200–17208. doi: 10.1021/ja4087769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bock CW, Katz AK, Glusker JP. Hydration of zinc ions: a comparison with magnesium and beryllium ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:3754–3765. doi: 10.1021/ja00118a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohtaki H, Radnai T. Structure and dynamics of hydrated ions. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1157–1204. doi: 10.1021/cr00019a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus Y. Ionic radii in aqueous solutions. Chem. Rev. 1988;88:1475–1498. doi: 10.1021/cr00090a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inada Y, Mohammed AM, Loeffler HH, Rode BM. Hydration structure and water exchange reaction of nickel(II) ion: classical and QM/MM simulations. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2002;106:6783–6791. doi: 10.1021/jp0155314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia Y, et al. Co2+ selectivity of Thermotoga maritima CorA and its inability to regulate Mg2+ homeostasis present a new class of CorA proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:16525–16532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.222166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibson MM, Bagga DA, Miller CG, Maguire ME. Magnesium transport in Salmonella typhimurium: the influence of new mutations conferring Co2+ resistance on the CorA Mg2+ transport system. Mol. Microbiol. 1991;5:2753–2762. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman M, et al. Probing metal ion substrate-binding to the E. coli ZitB exporter in native membranes by solid state NMR. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2008;25:683–690. doi: 10.1080/09687680802495267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lunin VV, et al. Crystal structure of the CorA Mg2+ transporter. Nature. 2006;440:833–837. doi: 10.1038/nature04642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthies D, et al. Cryo-EM structures of the magnesium channel CorA reveal symmetry break upon gating. Cell. 2016;164:747–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cleverley RM, et al. The Cryo-EM structure of the CorA channel from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii in low magnesium conditions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1848:2206–2215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfoh R, et al. Structural asymmetry in the magnesium channel CorA points to sequential allosteric regulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:18809–18814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209018109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romani AMP. Cellular magnesium homeostasis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011;512:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Outten CE, O’Halloran TV. Femtomolar sensitivity of metalloregulatory proteins controlling zinc homeostasis. Science. 2001;292:2488–2492. doi: 10.1126/science.1060331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang, D., Hurst, T. K., Thompson, R. B. & Fierke, C. A. Genetically encoded ratiometric biosensors to measure intracellular exchangeable zinc in Escherichia coli. J. Biomed. Opt. 16, 087011 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Elías A, et al. The ActP acetate transporter acts prior to the PitA phosphate carrier in tellurite uptake by Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Res. 2015;177:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maynaud G, et al. CadA of Mesorhizobium metallidurans isolated from a zinc-rich mining soil is a P(IB-2)-type ATPase involved in cadmium and zinc resistance. Res. Microbiol. 2014;165:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaoprasid P, Nookabkaew S, Sukchawalit R, Mongkolsuk S. Roles of Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 ZntA and ZntB and the transcriptional regulator ZntR in controlling Cd2+/Zn2+/Co2+ resistance and the peroxide stress response. Microbiology. 2015;161:1730–1740. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savitsky P, et al. High-throughput production of human proteins for crystallization: the SGC experience. J. Struct. Biol. 2010;172:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geertsma ER, Nik Mahmood NAB, Schuurman-Wolters GK, Poolman B. Membrane reconstitution of ABC transporters and assays of translocator function. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:256–266. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X, Zheng S, Agard DA, Cheng Y. Asynchronous data acquisition and on-the-fly analysis of dose fractionated cryoEM images by UCSFImage. J. Struct. Biol. 2015;192:174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X, et al. Electron counting and beam-induced motion correction enable near-atomic-resolution single-particle cryo-EM. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang K. Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol. 2016;193:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheres SHW. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheres SH. Beam-induced motion correction for sub-megadalton cryo-EM particles. Elife. 2014;3:e03665. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams PD, et al. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution; pp. 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJE. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dolinsky TJ, et al. PDB2PQR: expanding and upgrading automated preparation of biomolecular structures for molecular simulations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W522–W525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates and the corresponding electron microscopy density map are deposited in the Protein Data Bank and the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under accession number 5N9Y and EMD-3605, respectively. Other data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.