Abstract

Objective

Many studies have identified early-life risk factors for subsequent childhood overweight/obesity, but few have evaluated how they combine to influence risk of childhood overweight/obesity. We examined associations, individually and in combination, of potentially modifiable risk factors in the first 1000 days after conception with childhood adiposity and risk of overweight/obesity in an Asian cohort.

Methods

Six risk factors were examined: maternal pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2), paternal overweight/obesity at 24 months post-delivery, maternal excessive gestational weight gain, raised maternal fasting glucose during pregnancy (≥5.1 mmol/L), breastfeeding duration <4 months and early introduction of solid foods (<4 months). Associations between number of risk factors and adiposity measures [BMI, waist-to-height ratio(WHtR), sum of skinfolds(SSF), fat mass index(FMI) and overweight/obesity] at 48 months were assessed using multivariable regression models.

Results

Of 858 children followed up at 48 months, 172 (19%) had none, 274 (32%) had one, 244 (29%) had two, 126 (15%) had three and 42 (5%) had ≥4 risk factors. Adjusting for confounders, significant graded positive associations were observed between number of risk factors and adiposity outcomes at 48 months. Compared to children with no risk factors, those with 4 or more risk factors had SD-unit increases of 0.78 (95% CI 0.41-1.15) for BMI; 0.79 (0.41-1.16) for WHtR; 0.46 (0.06-0.83) for SSF and 0.67 (0.07-1.27) for FMI. The adjusted relative risk of overweight/obesity in children with four or more risk factors was 11.1(2.5-49.1) compared to children with no risk factors. Children exposed to maternal pre-pregnancy [11.8(9.8-13.8)%] or paternal overweight status [10.6(9.6-11.6)%] had the largest individual predicted probability of child overweight/obesity.

Conclusions

Early-life risk factors added cumulatively to increase childhood adiposity and risk of overweight/obesity. Early-life and preconception intervention programmes may be more effective in preventing overweight/obesity if they concurrently address these multiple modifiable risk factors.

Introduction

Recent findings have highlighted the importance of pre-conceptional health and nutrition on later offspring health(1, 2). Mounting evidence also suggests that the first 1000 days of life, spanning from conception to age 24 months, represents a crucial period for the development of later overweight/obesity, and hence an opportunity for prevention(3). A number of potentially modifiable risk factors spanning this important window, such as parental obesity(4, 5), excessive gestational weight gain (GWG)(6, 7), maternal smoking during pregnancy(8, 9), gestational glycemia(10, 11), and short breastfeeding duration(12, 13), have been positively associated with risk of subsequent childhood overweight or obesity. However, most prior studies have assessed these risk factors individually only; few have evaluated how they combine to influence risk of childhood overweight/obesity. To better understand their potential public health impact, these risk factors should be evaluated in combination, rather than one at a time. Gillman and Ludwig(14) reported that a combination of four modifiable risk factors (excessive GWG, smoking during pregnancy, breastfeeding <12 months and infant sleep <12 hours per day) predicted an obesity prevalence of 28% at 7-10 years, compared with 4% in children who had none of those risk factors. Similar findings were observed in a UK mother-offspring cohort, which reported that children with four or five risk factors (pre-pregnancy obesity, excessive GWG, smoking during pregnancy, breastfeeding <1 month and low maternal vitamin D) were at higher risk of developing obesity at 4 and 6 years, compared to children who had none(15). Neither of these studies however, included information on paternal overweight/obesity or maternal fasting glucose in their analyses. Both risk factors have been shown to impair subsequent metabolic health of offspring(16, 17) and are potentially modifiable through behavior change intervention (3, 18). Including paternal overweight/obesity and maternal fasting glucose in our analysis simultaneously allows comparison of their independent contributions to the offspring’s risk for subsequent overweight/obesity.

We are not aware of any similar studies conducted in Asian populations, whose susceptibility to obesity and metabolic disease differs from that of Europeans(19). Among school-going children in Singapore, the prevalence of overweight/obesity has risen steadily from 1.4% in 1976 to 11% in 2013(20). Therefore, studies on the relation between the combined effects of early-life risk factors on child overweight/obesity and direct measures of adiposity in Asian populations are needed to inform clinical practice and public health policies. Such information is increasingly important in Western countries as well, given current and future immigration patterns in those settings.

Using data from a prospective mother-offspring Asian cohort in Singapore, we aimed to examine the associations of six potentially modifiable risk factors in combination (maternal pre-pregnancy and paternal overweight, excessive GWG, raised fasting glucose (FPG) during pregnancy, duration of any breastfeeding <4 months and early solid food introduction) with adiposity and overweight/obesity at age 48 months. We hypothesized a positive and graded association between the number of these risk factors and child adiposity and risk of overweight/obesity.

Materials and Methods

Study population

The Growing Up in Singapore Towards healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) study has been previously described in detail(21). Briefly, pregnant women in their first trimester were recruited from two major public maternity hospitals in Singapore (KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital and National University Hospital) between June 2009 and September 2010. Of 3751 women screened, 2034 met eligibility criteria (detailed in Soh et al(21)), 1247 were recruited and 1170 had singleton deliveries (Supplemental Figure 1). Informed written consent was obtained from the women, and the study was approved by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board and SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board.

Maternal and paternal data

Socio-demographic data (age, self-reported ethnicity, education level and parity) were obtained at recruitment. Pregnant women underwent a 2-hour 75-g oral glucose tolerance test after an overnight fast at 26-28 weeks of gestation, as detailed previously(10). Women diagnosed with gestational diabetes, based on World Health Organization’s (WHO) criteria [FPG ≥7.0 mmol/L or 2-hour glucose ≥7.8 mmol/L], were placed on a diet and/or treated with insulin; these women were included in the analysis. Gestational age was assessed by trained ultrasonographers at the first dating scan after recruitment, and reported in completed weeks.

Maternal pre-pregnancy weight was self-reported at study enrollment. Measurements of weight and height for mothers (during pregnancy) and fathers (at 24 months post-delivery) were obtained using SECA 803 Weighing Scale and SECA 213 Stadiometer (SECA Corp, Hamburg, Germany). These measurements were used to calculate body mass index (BMI, in kg/m2) and GWG (in kg). GWG was calculated as the difference between final measured weight before delivery and pre-pregnancy weight.

Childhood data

Mothers were asked about infant milk feeding (as detailed previously(22)) and the age at which their child had been introduced to solid foods using interviewer-administered questionnaires. At 12 months, energy intake was derived using either a 24-h recall or a food diary. At 24 months, mothers were asked the average number of hours per day their child spent playing/exercising outdoors using interviewer-administered questionnaires.

At 48 months, measurements of weight, height, waist circumference and four skinfold thicknesses (triceps, biceps, subscapular and suprailiac) were obtained, as detailed previously(23). Anthropometric training and standardization sessions were conducted every 3 months; reliability was estimated by inter-observer technical error of measurement and coefficient of variation (Supplemental Table 1). Fat mass was measured in a subset of children (n=274) whose parents provided written consent when approached, using air displacement plethysmography (BOD POD®, Life Measurement Inc, Concord, CA, USA). These measurements were used to calculate BMI, sum of skinfolds (SSF, in mm), waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) and fat mass index (FMI, in kg/m2). Sex-specific BMI z-scores were calculated using the local Singapore(24) and WHO(25) references. Overweight/obesity was defined as sex-specific BMI >85th percentile of the local Singapore reference.

Risk factors

We selected four risk factors that have been empirically demonstrated to be independently associated with higher childhood adiposity in our cohort: pre-pregnancy BMI (ppBMI)(26), GWG(26), gestational hyperglycemia(10) and breastfeeding duration(27). We also selected two other risk factors that have previously been associated with childhood obesity: paternal BMI(28) and timing of solid food introduction(29). Maternal smoking during pregnancy was not included as a risk factor, owing to low prevalence in our study sample (2%), and was unrelated to child adiposity in previous analyses(30). Risk factor definitions were maternal pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity: ppBMI ≥25 kg/m2; paternal overweight/obesity: BMI ≥25 kg/m2; excessive GWG: Institute of Medicine 2009 guidelines(31); raised FPG during pregnancy: FPG ≥5.1 mmol/L (International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups criteria(32)); duration of any breastfeeding: <4 months; and early introduction of solid foods: <4 months(33). Risk factor scores were computed by calculating the cumulative number of risk factors for each individual, as described in previous studies(14, 15).

Statistical analysis

Child adiposity data (BMI, WHtR, SSF and FMI) were log-transformed and standardized to z-scores with a mean of 0 and SD of 1, which reduced the skewness and non-normality. Linear regression models were fitted with risk factor scores as a continuous predictor, or a categorical predictor using children with no risk factors as the reference. Parameter estimates were back-transformed to their original units, by multiplying them by the observed SD of the corresponding logged adiposity data, followed by exponentiation to the base 10. Logistic regression models were used to estimate probabilities of child overweight for different risk factor combinations. Poisson regression models with robust variance were used to estimate the relative risk of child overweight for each number of risk factors, with no risk factors as the reference. All models were adjusted for maternal education level, height, parity and ethnicity, along with child sex and actual age at measurement to improve precision. As these risk factors may be considered as markers of the child’s postnatal environment, the models were further adjusted for energy intake at 12 months and child physical activity level at 24 months (< 1, 1- <2 or ≥2 hours per day). Potential effect modification by ethnicity and sex was assessed by including multiplicative interaction terms with the risk factor scores in the fully adjusted model.

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted; first, as self-reported pre-pregnancy weight may have limited validity, we re-ran the analyses using maternal overweight at booking (mean 8.7 ± 2.8 weeks of gestation) as a risk factor instead. Second, three risk factor categorizations were changed: ppBMI and paternal BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (n=66 and 165 respectively), and FPG during pregnancy ≥5.6 mmol/L (n=10), according to National Institute of Health Care and Excellence 2015 guidelines(34). Third, child overweight was re-categorized according to International Obesity Task Force (IOTF)(35) (n=56) and WHO(25) (n=10) cutoffs. Lastly, missing values for any risk factors and/or covariates were imputed by multiple imputation, using the Markov-chain Monte Carlo technique generated from 20 imputed datasets. All analyses were performed using Stata 13 software (StataCorp LP, TX).

Results

Of 1170 infants delivered, 73.3% (n=858) were followed up at 48 months (Supplemental Figure 1). Between subjects with and without (n=312) follow-up data, no significant differences were observed in maternal and child characteristics, with the exception of breastfeeding duration and child physical activity (Supplemental Table 2). Among those followed up, maternal characteristics differed by ethnicity, including age, education level, parity, height and proportion with pre-pregnancy overweight, excessive GWG, raised FPG during pregnancy and short breastfeeding duration (Table 1). Compared to Chinese mothers, Malay mothers had lower educational attainment, were younger, shorter, more likely to be overweight, had excessive GWG, and less likely to breastfeed ≥4 months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants according to ethnicity

| Chinese (n=485) | Malay (n=217) | Indian (n=156) | p value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 31.9 ± 4.71 | 29.0 ± 5.53 | 30.2 ± 4.8 | <0.001 |

| Maternal education level | <0.001 | |||

| < 12 years | 144 (30)1 | 148 (68) | 43 (28) | |

| ≥ 12 years | 339 (70) | 67 (32)3 | 112 (72) | |

| Parity | 0.007 | |||

| Primiparous | 243 (50) | 90 (41) | 58 (37) | |

| Multiparous | 242 (50) | 127 (59) | 98 (63)3 | |

| Maternal height (cm) | 159 ± 6 | 157 ± 63 | 157 ± 53 | <0.001 |

| Pre-pregnancy overweight | <0.001 | |||

| No | 341 (76) | 95 (47) | 59 (41) | |

| Yes | 107 (24) | 105 (53)3 | 84 (59)3 | |

| Paternal overweight | 0.01 | |||

| No | 195 (54) | 69 (41) | 43 (43) | |

| Yes | 168 (46) | 98 (59)3 | 57 (57) | |

| Raised FPG during pregnancy | 0.006 | |||

| No | 442 (97) | 187 (92) | 125 (91) | |

| Yes | 15 (3) | 17 (8) | 12 (9)3 | |

| Excessive GWG4 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 286 (65) | 94 (48) | 77 (55) | |

| Yes | 156 (35) | 102 (52)3 | 64 (45) | |

| Any BF < 4 months4 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 229 (57) | 57 (33) | 64 (54) | |

| Yes | 171 (43) | 115 (67)3 | 54 (46) | |

| Early introduction to solids | 0.003 | |||

| No | 444 (99) | 176 (95) | 124 (95) | |

| Yes | 4 (1) | 9 (5)3 | 6 (5)3 | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38.4 ± 1.3 | 38.0 ± 1.33 | 38.1 ± 2.13 | 0.007 |

| Child gender | 0.65 | |||

| Male | 235 (48) | 97 (45) | 75 (48) | |

| Female | 250 (52) | 120 (55) | 81 (52) | |

| Child energy intake at 12-months (kcal) | 734 ± 187 | 806 ± 242 | 784 ± 205 | <0.001 |

| Child physical activity at 24-months | 0.04 | |||

| < 1 hour per day | 268 (61) | 137 (65) | 73 (49) | |

| 1 to < 2 hours per day | 123 (28) | 52 (25) | 54 (36) | |

| ≥ 2 hours per day | 49 (11) | 22 (10) | 23 (15) | |

| BMI at 48 months4 | 15.3 ± 1.4 | 16.1 ± 2.23 | 15.6 ± 2.3 | <0.001 |

| SSF at 48 months4 | 16.0 ± 3.8 | 17.1 ± 6.63 | 16.9 ± 6.9 | <0.001 |

| WHR at 48 months4 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 0.50 ± 0.043 | 0.49 ± 0.05 | <0.001 |

| FMI at 48 months4 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 4.0 ± 1.3 | 4.2 ± 1.73 | 0.02 |

Mean ± SD or n (%)

p value across 3 ethnic groups were determined with the use of a chi-square analysis (categorical) or 1-factor ANOVA (continuous)

p<0.05 compared with Chinese [determined with the use of a chi-square analysis (categorical) or 2-sample t-test]

GWG: gestational weight gain; BF: breastfeeding; BMI: body mass index; SSF: sum of skinfolds; WHR: waist-toheight ratio; FMI: fat mass index

Compared to Chinese children, Malay children had the highest BMI (16.1 vs 15.3 kg/m2), SSF (17.1 vs 16.0 mm) and WHtR (0.50 vs 0.48), while Indian children had the highest FMI (4.2 vs 3.7 kg/m2) at 48 months. 172 children (19%) had no risk factors, 274 (32%) had one, 244 (29%) had two, 126 (15%) had three and 42 (5%) had four or more risk factors (Supplemental Table 3). Children with no risk factors were more likely to be of Chinese ethnicity and born to mothers with higher educational attainment, while children with four or more risk factors were more likely to be of Malay ethnicity and born to mothers with lower educational attainment (Supplemental Table 4).

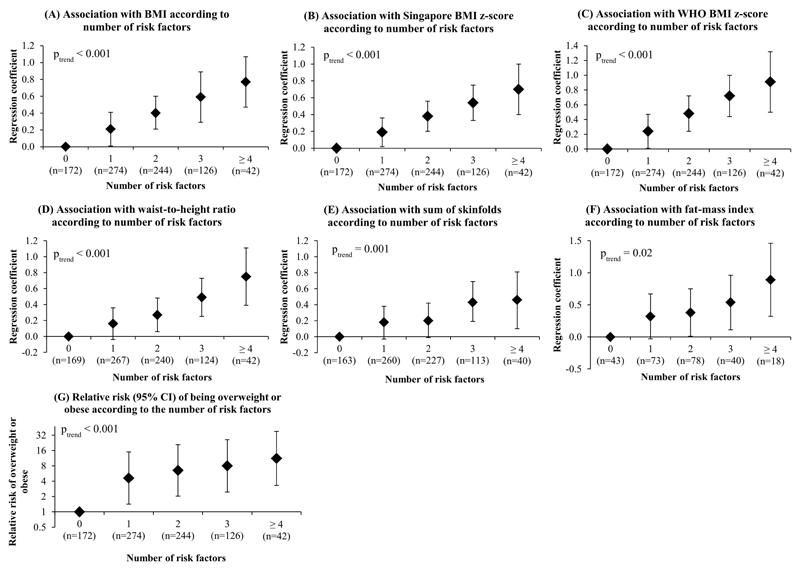

After adjusting for potential confounders, graded increases in BMI (Figure 1A), BMI z-score (Figures 1B–C), WHtR (Figure 1D), SSF (Figure 1E) and FMI (Figure 1F) were observed with increasing risk factor score. The linear trends were highly significant (ptrend < 0.001) for all adiposity outcomes: 0.21 (95% CI: 0.14-0.28) SD unit per additional risk factor for BMI; 0.19 (0.12-0.26) SD unit for WHtR; 0.12 (0.05-0.19) SD unit for SSF and 0.14 (0.02-0.25) SD unit for FMI. Children with four or more risk factors had increases of 0.78 (0.41-1.15) SD units for BMI; 0.79 (0.41-1.16) SD units for WHtR; 0.46 (0.06-0.83) SD units for SSF and 0.67 (0.07-1.27) SD units for FMI compared to those with no risk factors; this corresponded to differences of 1.1 kg/m2 for BMI, 1.1 for WHtR, 1.1 mm for SSF and 1.3 kg/m2 for FMI. The relative risk [RR (95% CI)] of child overweight was 1.5 (1.3-1.7) per additional risk factor, after adjusting for potential confounders. Children with four or more risk factors had the highest RR [11.1 (2.5-49.1)] compared to children who had none (Figure 1G). Further analyses showed that graded increases in adiposity and overweight risk with increasing risk factor score persisted even when maternal ppBMI was included as a covariate, rather than a risk factor in the model (Table 2), thereby supporting the observed additive effect. No interactions were observed between ethnicity and risk factor score, nor between child sex and risk factor score, for any of the outcomes.

Figure 1.

Associations with (A) BMI, (B) BMI z-score (Singapore reference), (C) WHO BMI z-score, (D) waist-to-height ratio, (E) sum of skinfolds, (F) fat mass index (subset n=274), and (G) relative risk of overweight or obese at 48 months, according to number of risk factors. All models were adjusted for maternal education level, height, parity, child daily physical activity level, total energy intake and ethnicity. Figures 1A, D-F were additionally adjusted for child sex and actual age at measurement. Data points represent regression coefficients (Figs 1A-F) or relative risk (Fig 1G) estimates; error bars represent 95% confidence intervals

Table 2.

Estimated regression coefficients and relative risk (95% CIs) of the associations between number of modifiable risk factors (paternal overweight, excessive GWG, BF < 4 months, raised glucose during pregnancy and early introduction of solid foods) with child adiposity and overweight/obesity risk at 48 months, independent of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI.

| Number of risk factors | BMI1 |

SG BMI z-score2,3 |

WHO BMI z-score2,4 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (95% CI) | p value | B (95% CI) | p value | B (95% CI) | p value | |

| 0 | ref | - | ref | - | ref | ref |

| 1 | 0.14 (-0.05, 0.33) | 0.15 | 0.14 (-0.02, 0.31) | 0.11 | 0.19 (-0.05, 0.43) | 0.12 |

| 2 | 0.28 (0.08, 0.48) | 0.01 | 0.27 (0.09, 0.44) | 0.002 | 0.42 (0.17, 0.66) | 0.001 |

| 3 | 0.39 (0.14, 0.65) | 0.003 | 0.34 (0.11, 0.56) | 0.003 | 0.43 (0.12, 0.74) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 4 | 0.45 (0.01, 0.89) | 0.04 | 0.38 (0.001, 0.76) | 0.05 | 0.67 (0.04, 1.30) | 0.04 |

| β-trend | 0.14 (0.06, 0.23) | <0.001 | 0.13 (0.05, 0.20) | 0.001 | 0.17 (0.07, 0.28) | 0.001 |

| Number of risk factors |

WHtR1 |

SSF1 |

FMI1,5 |

|||

| B (95% CI) | p value | B (95% CI) | p value | B (95% CI) | p value | |

| 0 | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - |

| 1 | 0.12 (-0.08, 0.33) | 0.22 | 0.08 (-0.12, 0.28) | 0.45 | 0.19 (-0.18, 0.56) | 0.31 |

| 2 | 0.27 (0.06, 0.48) | 0.01 | 0.18 (-0.03, 0.39) | 0.09 | 0.38 (0.04, 0.73) | 0.03 |

| 3 | 0.31 (0.05, 0.58) | 0.02 | 0.38 (0.11, 0.65) | 0.01 | 0.52 (0.04, 1.00) | 0.04 |

| ≥ 4 | 0.73 (0.20, 1.26) | 0.01 | 0.37 (-0.11, 0.85) | 0.13 | 0.75 (-0.10, 1.51) | 0.05 |

| β-trend | 0.13 (0.05, 0.22) | 0.002 | 0.08 (0.00, 0.16) | 0.05 | 0.16 (0.02, 0.29) | 0.02 |

| Number of risk factors |

Overweight by Singapore reference2 |

Overweight by IOTF reference2 |

Overweight by WHO reference2 |

|||

| Relative risk (95% CI) | p value | Relative risk (95% CI) | p value | Relative risk (95% CI) | p value | |

| 0 | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - |

| 1 | 1.62 (0.73-3.59) | 0.23 | 2.46 (0.74-8.21) | 0.14 | 4.24 (0.56-32.31) | 0.16 |

| 2 | 2.53 (1.15-5.56) | 0.02 | 4.40 (1.34-14.45) | 0.02 | 7.01 (1.00-51.70) | 0.05 |

| 3 | 2.49 (1.07-5.84) | 0.04 | 4.83 (1.42-16.42) | 0.01 | 8.62 (1.15-64.48) | 0.03 |

| ≥ 4 | 2.92 (1.09-7.87) | 0.03 | 5.48 (1.44-20.89) | 0.01 | 5.21 (0.58-47.15) | 0.14 |

| β-trend | 1.31 (1.04, 1.63) | 0.02 | 1.43 (1.09, 1.90) | 0.01 | 1.36 (1.06, 1.76) | 0.02 |

Adjusted for maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, education level, height, parity, child sex, daily physical activity level, total energy intake, ethnicity and actual age at measurement

Adjusted for maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, education level, height, parity, child daily physical activity level, total energy intake and ethnicity

BMI z-score calculated using local Singapore reference

BMI z-score calculated using WHO reference

FMI measured in a subset of infants (n=274)

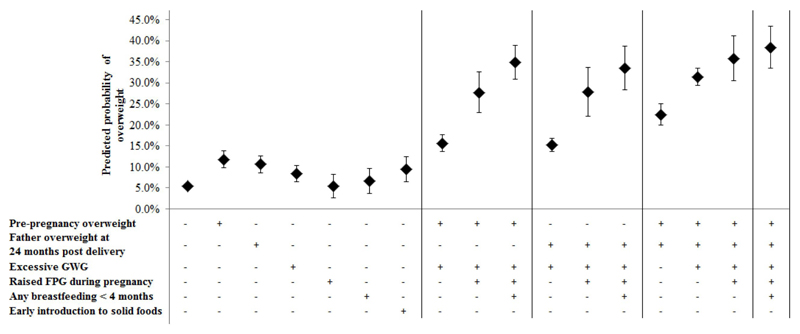

Figure 2 shows the adjusted predicted probability of child overweight/obesity for each risk factor, as well as different risk factor combinations. Children exposed to maternal pre-pregnancy or paternal overweight status had predicted probabilities of overweight/obesity of 11.8 (9.8-13.8)% and 10.6 (9.6-11.6)% respectively, which were the largest relative to the other individual risk factors. Risk factor combinations involving maternal pre-pregnancy or paternal overweight showed similar graded increases in estimated probability of child overweight/obesity, and these estimates were further amplified when risk factor combinations included both maternal pre-pregnancy and paternal overweight (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of overweight or obese at 48 months according to different risk factor combinations. “+” indicates presence of risk factor, “–” indicates absence of risk factor. All models were additionally adjusted for maternal education level, height, parity, child daily physical activity level, total energy intake and ethnicity

Sensitivity analyses showed that the observed associations were robust to replacing pre-pregnancy overweight with booking overweight (Supplemental Table 5), re-categorization of three risk factors (Supplemental Table 6), re-categorization of child overweight according to IOTF or WHO cutoffs (Supplemental Table 7), and multiple imputation for missing risk factors and/or covariates (Supplemental Table 6), which is reassuring with respect to potential for measurement or selection bias.

Discussion

By using risk factor categorizations defined a priori, we observed graded associations of an increasing risk factor score with higher child adiposity and overweight/obesity. Children with four or more risk factors showed an 11-fold increased risk of overweight/obesity compared to children with no risk factors, along with 1.1 mm and 1.3 kg/m2 increases in SSF and FMI, respectively. These associations remained after adjusting for potential confounders, child physical activity level, total energy intake, and after various sensitivity analyses. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to evaluate the combined effects of early-life risk factors on direct measures of adiposity in an Asian cohort.

Our findings are in line with those from cohort studies in the United States(14) and United Kingdom(15). In Project Viva, a 7-fold difference in predicted obesity prevalence was observed between 7-10-year-old children with four risk factors and those with none(14). In the Southampton Women’s Survey, a 4-fold difference in relative risk of overweight at 4 and 6 years was observed between children with four or five risk factors and those with none. Each risk factor assessed in our study is potentially modifiable through behavior change intervention. For example, interventions to limit GWG(36), promote breastfeeding duration(37) and educate mothers regarding timing of solid food introduction(38) have had some success. A recent randomized clinical trial has demonstrated the ability of an exercise intervention in reducing the incidence of gestational diabetes and improving glucose metabolism during pregnancy(18). Prevention of maternal pre-pregnancy overweight is often encouraged, but few interventions have successfully achieved persistent reductions in parental BMI, and we are aware of no randomized controlled trials that have assessed the effects of BMI-focused preconception interventions on pregnancy and infant outcomes(39). Interventions that aim to address other early-life risk factors concurrently may, however, amplify their individual positive effects on preventing childhood overweight/obesity.

These risk factors are known to be interlinked and may stem from maternal overweight; assortive mating would induce correlations between maternal and paternal BMI (40). In addition, maternal overweight or excessive GWG are known to increase the risk of gestational hyperglycemia(41). In some settings, overweight or hyperglycemic women are more likely to be referred for planned cesarean delivery (42, 43), which reduces the likelihood of initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding (44). Nevertheless, our observations of graded increases in adiposity and overweight risk with increasing risk factor score persisted independently of maternal ppBMI, thereby supporting the observed additive effect.

The risk factors assessed are socially patterned and reflect socio-economic inequalities in the population; children with none of the studied risk factors were more likely to be from a higher socio-economic background, while children with four or more risk factors were more likely to be from a disadvantaged background. Risk factors such as parental overweight, shorter breastfeeding duration and early solid food introduction are known to be more prevalent in low socio-economic status groups(22). Children with multiple risk factors may also be living in an “obesogenic” family environment established by their parents. Earlier studies have described the fathers’ role in their child’s feeding practices(45), fathers’ parenting style on their child’s BMI(46), and the father’s positive influence on their child’s physical activity involvement(47). A recent systematic review had found that early-life interventions effective at preventing childhood overweight focused on family-level behavior changes(3). Findings from a randomized controlled trial also showed positive effects of a “responsive parenting” intervention on reducing rapid infancy weight gain and early childhood overweight risk(48). Taken together, the evidence suggests that early-life interventions aimed at addressing childhood obesity should target not just mothers before and during pregnancy, but fathers as well, with meaningful and practical lifestyle guidance at the family-level.

It is noteworthy that parental overweight showed the largest association with child overweight. The positive relation between maternal ppBMI and child adiposity is widely recognized(49). Maternal ppBMI represents the mother’s nutritional status prior to conception and may reflect a genetic contribution to offspring adiposity. Our finding that paternal BMI is a significant risk factor of child overweight confirms the study of Freeman et al (50), which reported an overweight or obese father, but a healthy-weight mother, significantly increased the odds of child obesity. The influence of paternal obesity on subsequent offspring obesity could be driven by a persistent unhealthy paternal lifestyle, contributing to an obesogenic family environment, as well as inheritance of obesity susceptibility genetic variants(51). Recent animal studies by Fullston et al(52) and Carone et al(53) have described how paternal exposure to high-fat diet affects the metabolic function of offspring into late adulthood (52), which may be partly explained by epigenetic alterations to sperm caused by diet-induced obesity (53). More recently, Soubry et al(54) reported how children of obese fathers showed altered methylation levels at multiple genes involved in normal human growth and development, compared to children of non-obese fathers. This evidence, along with ours, suggests that paternal health is an important consideration when identifying offspring at risk for childhood overweight/obesity.

Strengths of our study include its prospective design, which is crucial for assessing the relationship between early-life risk factors and subsequent childhood overweight. We are aware of no similar studies previously conducted in Asian populations, and even those in Western populations have not considered paternal overweight/obesity or maternal fasting glucose during pregnancy. Our study also has the advantage of several measures of adiposity, including BMI, WHtR, skinfolds and fat mass. Limitations of our study include the fact that some cohort children were not followed up, and differences between included and excluded children might conceivably have biased our findings. Maternal pre-pregnancy weight was self-reported during study enrollment, which may be affected by recall limitation. However, our data showed a strong correlation between self-reported pre-pregnancy weight and measured booking weight (ρ = 0.96), and sensitivity analyses using booking overweight as a risk factor showed similar observations. Paternal BMI was obtained at 24 months post-delivery, rather than at pre-pregnancy. Nonetheless, BMI in adults is known to track strongly over time; fathers who were overweight at 24 months post-delivery were likely to have been overweight at pre-pregnancy as well.

Although other potentially modifiable risk factors for child overweight have been reported before (infant sleep duration(14), maternal smoking during pregnancy(14, 15) and maternal vitamin D(15)), they had no association with child overweight/obesity in our cohort(30, 55); hence, we did not include them in our analysis. In addition, while birthweight is known to be associated with childhood overweight/obesity (56), we did not include it as a risk factor because it is not directly modifiable through behavior change intervention. We were unable to account for childhood dietary patterns that may reflect exposure to an obesogenic environment. Our observed associations accounted for the child’s energy intake at 12 months, although we are aware that this may not be representative of their diet at later ages. There is an ongoing debate regarding the causal effect of some risk factors, such as breastfeeding duration or age at introduction of solid foods, on childhood obesity; such risk factors may act merely as markers of the postnatal environment(57, 58). As ours is an observational study, it is not possible to determine whether the associations observed are causal. Finally, our study lacked other obesity-related measures such as insulin, triglycerides and C-peptide, which would be helpful in understanding the long-term health implications of our findings.

In conclusion, our findings should help understand the contribution of multiple modifiable risk factors towards development of childhood overweight/obesity, especially in Asian populations. Interventions to prevent childhood obesity may be more effective if conducted early in life or during pre-conception(59). Novel approaches during the first 1000 days of life may help prevent obesity and its long-term adverse consequences.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information is available at International Journal of Obesity’s website

Acknowledgements

The GUSTO study group includes Allan Sheppard, Amutha Chinnadurai, Anne Eng Neo Goh, Anne Rifkin-Graboi, Anqi Qiu, Arijit Biswas, Bee Wah Lee, Birit F.P. Broekman, Boon Long Quah, Borys Shuter, Carolina Un Lam, Chai Kiat Chng, Cheryl Ngo, Choon Looi Bong, Christiani Jeyakumar Henry, Claudia Chi, Cornelia Yin Ing Chee, Yam Thiam Daniel Goh, Doris Fok, E Shyong Tai, Elaine Tham, Elaine Quah Phaik Ling, Evelyn Xiu Ling Loo, Falk Mueller- Riemenschneider, George Seow Heong Yeo, Helen Chen, Heng Hao Tan, Hugo P S van Bever, Iliana Magiati, Inez Bik Yun Wong, Ivy Yee-Man Lau, Jeevesh Kapur, Jenny L. Richmond, Jerry Kok Yen Chan, Joanna D. Holbrook, Joanne Yoong, Joao N. Ferreira, Jonathan Tze Liang Choo, Joshua J. Gooley, Kenneth Kwek, Kok Hian Tan, Krishnamoorthy Niduvaje, Kuan Jin Lee, Leher Singh, Lieng Hsi Ling, Lin Lin Su, Lourdes Mary Daniel, Marielle V. Fortier, Mark Hanson, Mary Rauff, Mei Chien Chua, Mary Foong-Fong Chong, Melvin Khee-Shing Leow, Michael Meaney, Neerja Karnani, Ngee Lek, Oon Hoe Teoh, P. C. Wong, Paulin Tay Straughan, Pratibha Agarwal, Queenie Ling Jun Li, Rob M. van Dam, Salome A. Rebello, See Ling Loy, S. Sendhil Velan, Seng Bin Ang, Shang Chee Chong, Sharon Ng, Shiao-Yng Chan, Shirong Cai, Sok Bee Lim, Stella Tsotsi, Chin-Ying Stephen Hsu, Sue Anne Toh, Swee Chye Quek, Victor Samuel Rajadurai, Walter Stunkel, Wee Meng Han, Yin Bun Cheung, Yiong Huak Chan, and Zhongwei Huang.

Funding

This study is under Translational Clinical Research (TCR) Flagship Programme on Developmental Pathways to Metabolic Disease, NMRC/TCR/004-NUS/2008; NMRC/TCR/012-NUHS/2014 funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF) and administered by the National Medical Research Council (NMRC), Singapore. KMG is supported by the National Institute for Health Research through the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre and by the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013), project EarlyNutrition under grant agreement n°289346.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Keith M Godfrey, Yap Seng Chong and Yung Seng Lee have received reimbursement for speaking at conferences sponsored by companies selling nutritional products. Keith M Godfrey and Yap Seng Chong are part of an academic consortium that has received research funding from Abbot Nutrition, Nestec and Danone. All other authors declare no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Clinical Trial Registration

This study is registered under the Clinical Trials identifier NCT01174875; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01174875?term=GUSTO&rank=2

References

- 1.Corchia C, Mastroiacovo P. Health promotion for children, mothers and families: here's why we should "think about it before conception". Ital J Pediatr. 2013 Oct 25;39:68. doi: 10.1186/824-7288-39-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss JL, Harris KM. Impact of maternal and paternal preconception health on birth outcomes using prospective couples' data in Add Health. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015 Feb;291(2):287–98. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3521-0. Epub 2014 Nov 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake-Lamb TL, Locks LM, Perkins ME, Woo Baidal JA, Cheng ER, Taveras EM. Interventions for Childhood Obesity in the First 1,000 Days A Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Jun;50(6):780–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.010. Epub 6 Feb 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lake JK, Power C, Cole TJ. Child to adult body mass index in the 1958 British birth cohort: associations with parental obesity. Arch Dis Child. 1997 Nov;77(5):376–81. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.5.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godfrey KM, Reynolds RM, Prescott SL, Nyirenda M, Jaddoe VW, Eriksson JG, et al. Influence of maternal obesity on the long-term health of offspring. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Jan;5(1):53–64. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30107-3. Epub 2016 Oct 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diesel JC, Eckhardt CL, Day NL, Brooks MM, Arslanian SA, Bodnar LM. Is gestational weight gain associated with offspring obesity at 36 months? Pediatr Obes. 2015 Aug;10(4):305–10. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.262. Epub 2014 Sep 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oken E, Taveras EM, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. Gestational weight gain and child adiposity at age 3 years. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Apr;196(4):322.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorog K, Pattenden S, Antova T, Niciu E, Rudnai P, Scholtens S, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and childhood obesity: results from the CESAR Study. Matern Child Health J. 2011 Oct;15(7):985–92. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0543-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Kries R, Toschke AM, Koletzko B, Slikker W., Jr Maternal smoking during pregnancy and childhood obesity. Am J Epidemiol. 2002 Nov 15;156(10):954–61. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aris IM, Soh SE, Tint MT, Saw SM, Rajadurai VS, Godfrey KM, et al. Associations of gestational glycemia and prepregnancy adiposity with offspring growth and adiposity in an Asian population. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Nov;102(5):1104–12. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.117614. Epub 2015 Sep 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woo Baidal JA, Locks LM, Cheng ER, Blake-Lamb TL, Perkins ME, Taveras EM. Risk Factors for Childhood Obesity in the First 1,000 Days: A Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Jun;50(6):761–79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.012. Epub 6 Feb 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buyken AE, Karaolis-Danckert N, Remer T, Bolzenius K, Landsberg B, Kroke A. Effects of breastfeeding on trajectories of body fat and BMI throughout childhood. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008 Feb;16(2):389–95. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Araujo CL, Victora CG, Hallal PC, Gigante DP. Breastfeeding and overweight in childhood: evidence from the Pelotas 1993 birth cohort study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006 Mar;30(3):500–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillman MW, Ludwig DS. How early should obesity prevention start? N Engl J Med. 2013 Dec 5;369(23):2173–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1310577. Epub 2013 Nov 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson SM, Crozier SR, Harvey NC, Barton BD, Law CM, Godfrey KM, et al. Modifiable early-life risk factors for childhood adiposity and overweight: an analysis of their combined impact and potential for prevention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Feb;101(2):368–75. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.094268. Epub 2014 Dec 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lane M, Zander-Fox DL, Robker RL, McPherson NO. Peri-conception parental obesity, reproductive health, and transgenerational impacts. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Feb;26(2):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.11.005. Epub Dec 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiersch L, Yogev Y. Impact of gestational hyperglycemia on maternal and child health. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014 May;17(3):255–60. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang C, Wei Y, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Xu Q, Su S, et al. Effect of Regular Exercise Commenced in Early Pregnancy on the Incidence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Overweight and Obese Pregnant Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care. 2016 Oct;39(10):e163–4. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurpad AV, Varadharajan KS, Aeberli I. The thin-fat phenotype and global metabolic disease risk. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011 Nov;14(6):542–7. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32834b6e5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foo LL, Vijaya K, Sloan RA, Ling A. Obesity prevention and management: Singapore's experience. Obes Rev. 2013 Nov;14(Suppl 2):106–13. doi: 10.1111/obr.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soh SE, Tint MT, Gluckman PD, Godfrey KM, Rifkin-Graboi A, Chan YH, et al. Cohort profile: Growing Up in Singapore Towards healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) birth cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2014 Oct;43(5):1401–9. doi: 10.093/ije/dyt125. Epub 2013 Aug 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pang WW, Aris IM, Fok D, Soh SE, Chua MC, Lim SB, et al. Determinants of Breastfeeding Practices and Success in a Multi-Ethnic Asian Population. Birth. 2016 Mar;43(1):68–77. doi: 10.1111/birt.12206. Epub 2015 Dec 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aris IM, Bernard JY, Chen LW, Tint MT, Pang YW, Lim WY, et al. Infant body mass index peak and early childhood cardio-metabolic risk markers in a multi-ethnic Asian birth cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2016 Sep 20;20 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Healthcare Group Polyclinics. Age and gender-specific national BMI cut-offs (Singapore) 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Onis M. WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006 Apr;450:76–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin X, Aris IM, Tint MT, Soh SE, Godfrey KM, Yeo GS, et al. Ethnic Differences in Effects of Maternal Pre-Pregnancy and Pregnancy Adiposity on Offspring Size and Adiposity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Oct;100(10):3641–50. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1728. Epub 2015 Jul 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aris IM, Soh SE, Tint MT, Saw SM, Rajadurai VS, Godfrey KM, et al. Associations of infant milk feed type on early postnatal growth of offspring exposed and unexposed to gestational diabetes in utero. Eur J Nutr. 2015 Sep 28;28:28. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-1057-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kubota M, Nagai A. Recent Advances in Obesity in Children. Avid Science; 2015. Factors Associated with Childhood Obesity in Asian Countries: A Review of Recent Literature. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huh SY, Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, Oken E, Gillman MW. Timing of solid food introduction and risk of obesity in preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2011 Mar;127(3):e544–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0740. Epub 2011 Feb 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Y, Aris IM, Tan SS, Cai S, Tint MT, Krishnaswamy G, et al. Sleep duration and growth outcomes across the first two years of life in the GUSTO study. Sleep Med. 2015 Oct;16(10):1281–6. doi: 10.016/j.sleep.2015.07.006. Epub Jul 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute of Medicine. Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. Washington, DC: The National Acadamines Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, Buchanan TA, Catalano PA, Damm P, et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010 Mar;33(3):676–82. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huh SY, Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, Oken E, Gillman MW. Timing of Solid Food Introduction and Risk of Obesity in Preschool-Aged Children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):e544–e51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Diabetes in pregnancy: management from preconception to the postnatal period 2015. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng3. [PubMed]

- 35.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000 May 6;320(7244):1240–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanentsapf I, Heitmann BL, Adegboye AR. Systematic review of clinical trials on dietary interventions to prevent excessive weight gain during pregnancy among normal weight, overweight and obese women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011 Oct 26;11:81. doi: 10.1186/471-2393-11-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kramer MS. "Breast is best": The evidence. Early Hum Dev. 2010 Nov;86(11):729–32. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.08.005. Epub Sep 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paul IM, Savage JS, Anzman SL, Beiler JS, Marini ME, Stokes JL, et al. Preventing Obesity during Infancy: A Pilot Study. Obesity. 2011;19(2):353–61. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Opray N, Grivell RM, Deussen AR, Dodd JM. Directed preconception health programs and interventions for improving pregnancy outcomes for women who are overweight or obese. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jul;14(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010932.pub2. CD010932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abrevaya J, Tang H. Body mass index in families: spousal correlation, endogeneity, and intergenerational transmission. Empirical Economics. 2011;41(3):841–64. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang C, Rawal S, Chong YS. Risk factors for gestational diabetes: is prevention possible? Diabetologia. 2016 Jul;59(7):1385–90. doi: 10.007/s00125-016-3979-3. Epub 2016 May 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheiner E, Levy A, Menes TS, Silverberg D, Katz M, Mazor M. Maternal obesity as an independent risk factor for caesarean delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004 May;18(3):196–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorgal R, Goncalves E, Barros M, Namora G, Magalhaes A, Rodrigues T, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus: a risk factor for non-elective cesarean section. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012 Jan;38(1):154–9. doi: 10.1111/j.447-0756.2011.01659.x. Epub 2011 Oct 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hobbs AJ, Mannion CA, McDonald SW, Brockway M, Tough SC. The impact of caesarean section on breastfeeding initiation, duration and difficulties in the first four months postpartum. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016 Apr 26;16:90. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0876-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johannsen DL, Johannsen NM, Specker BL. Influence of parents' eating behaviors and child feeding practices on children's weight status. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006 Mar;14(3):431–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wake M, Nicholson JM, Hardy P, Smith K. Preschooler obesity and parenting styles of mothers and fathers: Australian national population study. Pediatrics. 2007 Dec;120(6):e1520–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Finn K, Johannsen N, Specker B. Factors associated with physical activity in preschool children. J Pediatr. 2002 Jan;140(1):81–5. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.120693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Savage JS, Birch LL, Marini M, Anzman-Frasca S, Paul IM. Effect of the insight responsive parenting intervention on rapid infant weight gain and overweight status at age 1 year: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reilly JJ, Armstrong J, Dorosty AR, Emmett PM, Ness A, Rogers I, et al. Early life risk factors for obesity in childhood: cohort study. BMJ. 2005 Jun 11;330(7504):1357. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38470.670903.E0. Epub 2005 May 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freeman E, Fletcher R, Collins CE, Morgan PJ, Burrows T, Callister R. Preventing and treating childhood obesity: time to target fathers. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012 Jan;36(1):12–5. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.198. Epub Oct 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Isganaitis E, Suehiro H, Cardona C. Who's your daddy?: paternal inheritance of metabolic disease risk. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017 Feb;24(1):47–55. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fullston T, Ohlsson Teague EM, Palmer NO, DeBlasio MJ, Mitchell M, Corbett M, et al. Paternal obesity initiates metabolic disturbances in two generations of mice with incomplete penetrance to the F2 generation and alters the transcriptional profile of testis and sperm microRNA content. FASEB J. 2013 Oct;27(10):4226–43. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-224048. Epub 2013 Jul 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carone BR, Fauquier L, Habib N, Shea JM, Hart CE, Li R, et al. Paternally Induced Transgenerational Environmental Reprogramming of Metabolic Gene Expression in Mammals. Cell. 2010;143(7):1084–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soubry A, Murphy SK, Wang F, Huang Z, Vidal AC, Fuemmeler BF, et al. Newborns of obese parents have altered DNA methylation patterns at imprinted genes. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015 Apr;39(4):650–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.193. Epub Oct 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ong YL, Quah PL, Tint MT, Aris IM, Chen LW, van Dam RM, et al. The association of maternal vitamin D status with infant birth outcomes, postnatal growth and adiposity in the first 2 years of life in a multi-ethnic Asian population: the Growing Up in Singapore Towards healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) cohort study. Br J Nutr. 2016 Aug;116(4):621–31. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516000623. Epub 2016 Jun 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qiao Y, Ma J, Wang Y, Li W, Katzmarzyk PT, Chaput JP, et al. Birth weight and childhood obesity: a 12-country study. Int J Obes Suppl. 2015 Dec;5(Suppl 2):S74–9. doi: 10.1038/ijosup.2015.23. Epub Dec 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kramer MS, Guo T, Platt RW, Shapiro S, Collet JP, Chalmers B, et al. Breastfeeding and infant growth: biology or bias? Pediatrics. 2002 Aug;110(2 Pt 1):343–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kramer MS, Matush L, Vanilovich I, Platt RW, Bogdanovich N, Sevkovskaya Z, et al. Effects of prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding on child height, weight, adiposity, and blood pressure at age 6.5 y: evidence from a large randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007 Dec;86(6):1717–21. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Godfrey KM, Cutfield W, Chan SY, Baker PN, Chong YS. Nutritional Intervention Preconception and During Pregnancy to Maintain Healthy Glucose Metabolism and Offspring Health ("NiPPeR"): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2017 Mar 20;18(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1875-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.