Abstract

The emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections with multi-drug resistance needs effective and alternative control strategies. In this study we investigated the adjuvant effect of a novel furan fatty acid, 7,10-epoxyoctadeca-7,9-dienoic acid (7,10-EODA) against multidrug-resistant S. aureus (MDRSA) strain 01ST001 by disc diffusion, checker board and time kill assays. Further the membrane targeting action of 7,10-EODA was investigated by spectroscopic and confocal microscopic studies. 7,10-EODA exerted synergistic activity along with β-lactam antibiotics against all clinical MRSA strains, with a mean fractional inhibitory concentration index below 0.5. In time-kill kinetic study, combination of 7,10-EODA with oxacillin, ampicillin, and penicillin resulted in 3.8–4.2 log10 reduction in the viable counts of MDRSA 01ST001. Further, 7,10-EODA dose dependently altered the membrane integrity (p < 0.001) and increased the binding of fluorescent analog of penicillin, Bocillin-FL to the MDRSA cells. The membrane action of 7,10-EODA further facilitated the uptake of several other antibiotics in MDRSA. The results of the present study suggested that 7,10-EODA could be a novel antibiotic adjuvant, especially useful in repurposing β-lactam antibiotics against multidrug-resistant MRSA.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12088-017-0680-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Furan fatty acids; 7,10-Epoxyoctadeca-7,9-dienoic acid; Synergistic antibacterial agent; β-Lactam antibiotics; Multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Introduction

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is an important human pathogen associated with many clinical conditions [1, 2]. Development of multidrug-resistance in MRSA [3] severely impacts public health. According to World Health Organizations, MDRSA annually cause 19,000 deaths in US alone [4]. The increasing healthcare burden of MDRSA has led researcher to consider new control strategies. One attractive approach is to repurpose old antibiotics with unorthodox combinations of natural products against MDRSA. Antibiotic adjuvants have been reported to reduce the antibiotic resistance of pathogens [5]. Several plant extracts, food-products and essential oils have been used to repurpose various classes of antibiotics against MDRSA [6]. Nonetheless, huge clinical demand exists for novel non-antibiotic adjuvants with multiple health benefits.

Fatty acids are important structural and functional molecules in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. The importance of various free fatty acids as antimicrobials in food, agriculture, and biomedical fields has been reviewed [7]. Natural furan fatty acids possess cardioprotective, neuroprotective, radical scavenging, anti-inflammatory and antifungal properties [8–12]. However, antimicrobial properties of furan fatty acids are not investigated and hence remained unknown. Recently, a novel furan fatty acid, 7,10-epoxyoctadeca-7,9-dienoic acid (7,10-EODA), was produced using a dihydroxy fatty acid [13]. Earlier, we reported the antimicrobial potential of 7,10-EODA with the ability of sub-lethal concentration to reduce the virulence factor production in MRSA [14]. Based on this report, we postulated that sub lethal concentration of 7,10-EODA could also exert adjuvant activity with commercial antibiotics against MDRSA. In the present study, we investigated the antibiotic adjuvant potential of 7,10-EODA with several commercial antibiotics. Further we describe the β-lactam antibiotic potentiating ability of 7,10-EODA against MDRSA and specific membrane targeting role of 7,10-EODA in this process.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

All Antibiotics and solvent (dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO) used in the present study were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ethidium bromide (EtBr), Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP), 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and Bocillin-FL were purchased from life technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The 7,10-EODA (> 95% pure) was produced according to a previously described method [13].

Strains and Growth Conditions

Clinical isolates of MRSA strains 01ST001, 165, 018, and 093, 02ST 085, 136, 03ST 120, were obtained from National Culture Collection for Pathogen (Osong, South Korea), a member of world data center for microorganisms (WDCM 852). Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (ATCC 29213) was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Baltimore, USA). S. aureus 1199 and 1199B (clinical isolates) were kind gift from Dr. G. W. Kaatz (Wayne State University, MI, USA). All strains were grown in either trypticase soy broth (TSB) or nutrient broth (NB) purchased from Becton–Dickinson (Cockeysville, MD, USA). Strains were stored at – 80 °C in NB containing 30% glycerol.

Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The MIC of the test agents was determined according to CLSI guidelines [15]. Briefly, each test sample was prepared in a 2-fold serial dilution in Mueller–Hinton Broth (MHB) in 96-well microtiter plates. Mid-log phase bacteria were diluted 10-fold with MHB (5 × 105 c.f.u/ml), and 0.1-ml aliquots were added to the wells and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The optical density of cell growth was determined at 610 nm (OD610). The minimum concentration required to prevent > 90% cell growth was considered as MIC.

Antibiotic Adjuvant Screening by Disc Diffusion Assay

For antibiotic adjuvant screening, TSA plates were seeded with 5 × 105 CFU/ml of MDRSA01ST001 and ATCC 29213 cultures and placed with two sets of sterile filter paper discs. One set was impregnated with antibiotics (1/4MIC), and the other set was impregnated with the mixture of antibiotics and 7,10-EODA (1/4MIC, 31.2 µg). Discs containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 7,10-EODA (1/4MIC) alone served as controls. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Potential synergistic effect was inferred when the size of the zone of inhibition (ZOI) was ≥ 5 mm (≥ 70%) around the antibiotic and 7,10-EODA containing discs.

Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index Determination

The interaction between selected antibiotics and 7,10-EODA was evaluated by the checker board method [16]. Two-fold serial dilutions of 7,10-EODA and test antibiotics (2 × MIC) from a stock were prepared in the columns and the rows of a 96-well microtiter plate to obtain combinations of 7,10-EODA and antibiotics at various concentrations. Then, test strains (5 × 105 CFU/ml) was added to the well of microtiter plate and incubated without shaking at 37 °C for 24 h. At the end of the incubation, cell growth (OD610) was determined using spectrophotometer (Tecan M200 Infinite Pro, Mannedorf, Switzerland). The FIC index (FICI) was calculated as follows: FICI = FIC A + FIC B, where FIC A is MIC of drug a in combination/MIC of drug a alone and FIC B is MIC of drug B in combination/MIC of drug B alone. FICI was as follows: ≤ 0.5, synergy; > 0.5 to ≤ 1.0, additive; > 1.0 to ≤ 4.0, indifference, and > 4.0, antagonism.

In-Vitro Time Kill Kinetics

Glass tubes containing β-lactam antibiotics (1/4MIC) or 7,10-EODA (1/8 and 1/4MIC) or a combination there of in 10 ml of MHB were inoculated with of MDRSA01ST001 (5 × 105 CFU/ml). DMSO (10 µl) treated samples served as negative controls. The treatments were incubated at 37 °C in a shaking incubator (150 rpm) for 24 h. At 0, 3, 6, and 24 h, culture suspension (0.1 ml) was aseptically removed and serially diluted and plated on MHA plates and viable counts were determined.

EtBr Uptake Assay

The membrane integrity was determined according the method of [17] with slight modifications. Briefly, cell suspension of mid-log phase cells of MDRSA 001 (0.5 OD610) was prepared in 1 ml of PBS (pH 7.4). Aliquots (0.1 ml) were transferred to the wells of microtiter plate containing 0.1 ml PBS (pH 7.4) containing 7,10-EODA (15.6–31.2 µg/ml). CCCP (A proton motive force disrupting agent) served as positive control. Finally EtBr (5 µM) was added to each well and the fluorescence intensity of cells was monitored at 360 nm (exi) and 616 nm (emi) wavelengths using fluorescence spectrophotometer (Tecan M200 Infinite Pro, Mannedorf, Switzerland) till 30 min. The relative final fluorescence was determined using the formula; RFF = (Fcompound − Fcontrol)/Fcontrol, where Fcompound corresponds to the fluorescence of the EtBr accumulation curve at 30 min in the presence of a 7,10-EODA. Fcontrol is the fluorescence of the EtBr accumulation curve at 30 min in the absence of 7,10-EODA.

Visualization of Bacterial Cell Membrane Permeation

MDRSA 01ST001 cells (2 × 105 CFU/ml) was treated with 7,10-EODA (0–31.2 µg/ml) in MHB for 1 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000×g for 5 min, washed twice with PBS (pH 7.4), and then incubated with DAPI/PI (5 µM) for 5 min. After harvesting and three washes with PBS, the cell pellet was resuspended in PBS, and a 10-µl aliquot of the sample was mounted on a 1% agarose pad and imaged using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon Co., Tokyo, Japan) with an excitation wavelength of 494 nm.

Bocillin Binding Study

The effect of 7,10-EODA on the Bocillin-FL binding was studied according to the method of [18] with slight modifications. Briefly, the MDRSA 01ST001 in TSB medium and antibiotics were added with Bocillin-FL (2 μg/ml) or a combination of Bocillin-FL (2 μg/ml) and 7,10-EODA (15.6 or 31.2 μg/ml). After 30 min incubation, cultures were centrifuged at 9000×g for 4 min, washed four times with PBS and ground with 0.2 µm glass beads for 15 min and resuspended in a 0.1 ml of saline. The Bocillin-FL fluorescence was determined by microplate reader (Tecan M200 Infinite Pro, Mannedorf, Switzerland) operated at 485 nm (exc) and 530 nm (emi) wavelengths, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Where applicable the data were analyzed for statistical significance by a two tailed student’s t test for unpaired data using Graph Pad Prism’version 5.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

7,10-EODA Exhibits Selective β-Lactam Potentiation Activity

MRSA 01ST001 shows resistance to multiple antibiotics (Fig. S1) and hence it is referred as MDRSA 01ST001 in this study. In viability assays, 7,10-EODA (125 µg/ml) was bactericidal (3.6 log10 reduction). However, sub MIC of 7,10-EODA (15.6, 31.2 µg/ml) showed no growth inhibition against MDRSA 01ST001 (Fig. 1). The results of antibiotic adjuvant screening suggested that 7,10-EODA (31.2 µg/ml) increased the size of ZOI of β-lactam antibiotics (oxacillin, ampicillin, and penicillin) by 92–135% when compared to antibiotic controls (Table 1). A representative synergistic interaction between 7,10-EODA and penicillin against MDRSA 01ST001 was represented in Fig. 2. Interestingly, 7,10-EODA could not sensitize β-lactams against methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA, ATCC 29213). All other antibiotics had nil to moderate activity (falling below 70% cutoff).

Fig. 1.

Determination of susceptibility of MDRSA01ST001 to 7,10-EODA treatment. MDRSA 01ST001 cells (5 × 105 CFU/ml) were cultured in presence of 7,10-EODA (0–125 µg/ml) in MHB (10 ml) at 37 °C for 24 h. A 1 ml aliquot from each treatment was serially diluted in saline and 0.1 ml was placed on MHA for viable counts. Mean log CFU/ml ± SD value was given (n = 4). Student’s t test: *** p < 0.001 compared with controls. The line spanning two adjacent bars are not significantly different (ns) form controls

Table 1.

Antibiotic adjuvant effect of 7,10-EODA against methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive S. aureus

| Antibiotica | MIC (µg/ml) | ZOI (mm) without/with 7,10-EODAb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01ST001 | 29213 | MRSA01ST001 | ATCC29213 | |

| STP | 62.5 | 3 | 6.0 ± 0.0/12.9 ± 0.2 | 6.0 ± 0.0/11.4 ± 0.7 |

| CIP | 6.0 | 2.5 | 6.0 ± 0.0/13.2 ± 0.1 | 9.6 ± 0.2/13.2 ± 0.2 |

| CPL | 10 | 10 | 13.2 ± 0.4/13.9 ± 0.4 | 7.4 ± 0.2/7.21 ± 0.2 |

| CPZ | 62.5 | 125.0 | 7.2 ± 0.1/12.0 ± 0.5 | 6.0 ± 0.0/8.05 ± 0.5 |

| RIF | 5 | 5 | 18.3 ± 0.2/20.2 ± 0.1 | 21.0 ± 0.8/23.7 ± 1.2 |

| IRG | 0.1 | 0.1 | 12.4 ± 0.3/13.8 ± 1.1 | 11.1 ± 0.5/10.0 ± 0.3 |

| TMP | 7.8 | 7.8 | 6.0 ± 0.0/6.00 ± 0.0 | 8.9 ± 0.1/12.3 ± 0.2 |

| OXA | 62.5 | 0.04 | 6.0 ± 0.1/14.1 ± 0.2 | 8.3 ± 0.1/9.60 ± 0.4 |

| AMP | 1000 | 1.97 | 7.3 ± 0.2/14.2 ± 0.6 | 16.9 ± 0.3/17.0 ± 0.5 |

| CEP | 1000 | 1.97 | 10.1 ± 1.3/13.1 ± 0.6 | 15.3 ± 0.1/15.3 ± 0.2 |

| PEN | 1000 | 0.5 | 7.1 ± 0.1/13.6 ± 0.5 | 12.9 ± 0.4/13.2 ± 0.4 |

a STP streptomycin, CIP ciprofloxacin, CPL chloramphenicol, CPZ chlorpromazine, RIF rifampicin, IRG irgasan, TMP trimethoprim, OXA oxacillin, AMP ampicillin, CEP cephalexin, PEN penicillin

bThe antibiotics and 7,10-EODA used for synergy was 1/4 MIC and 1/4 MIC (31.2 µg), respectively

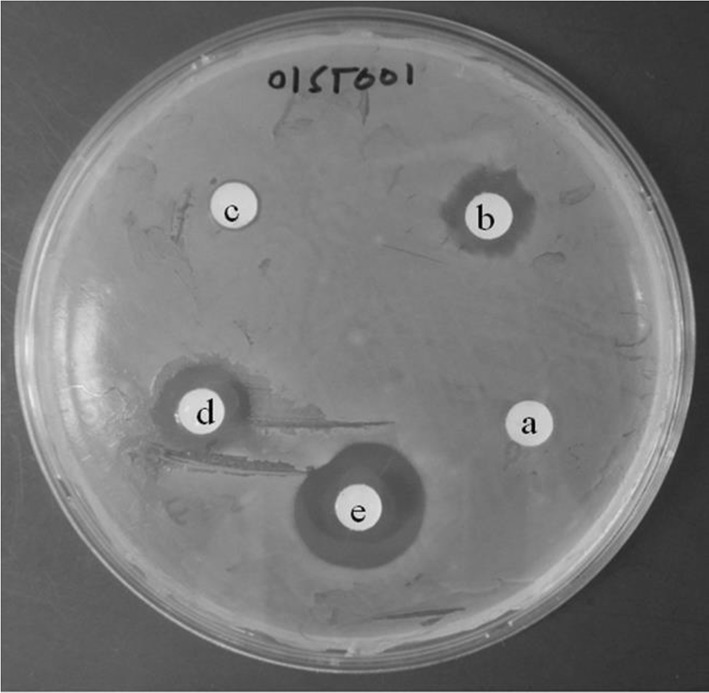

Fig. 2.

Representative adjuvant screening agar plate exhibiting a potential synergy between penicillin and 7,10-EODA in MDRSA01ST001. Disc a penicillin (5 µg), b penicillin (125 µg), c 7,10-EODA (31.2 µg). d Penicillin (5 µg) + 7,10-EODA (31.2 µg), e penicillin (125 µg) + 7,10-EODA (31.2 µg), All compounds were dissolved in DMSO (20 µl)

Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index

In primary screening, 7,10-EODA was identified as a potentiator of β-lactam activity against MDRSA 01ST001. The interaction between the combinations of 7,10-EODA and β-lactam antibiotics was confirmed in clinically relevant MRSA strains using checker board assay. As summarized in the Table 2, the FIC indices of oxacillin, ampicillin, and penicillin were from 0.15–0.62, 0.18–0.62, and 0.28–0.74, in combination with 15.6 and 31.2 µg/ml of 7, 10-EODA against MRSA isolates. Specifically in 01ST001, the MIC of oxacillin (62.5 µg/ml) and ampicillin (1000 µg/ml) was reduced by 4 and 16 folds in the presence of 15.6 and 31.2 µg/ml of 7,10-EODA, respectively. Similarly, the MIC of penicillin (500 µg/ml) was reduced by 2 and 16 folds in the presence of 15.6 and 31.2 µg/ml of 7,10-EODA, respectively. 7,10-EODA exhibited indifference (FICI, 2.0) against E. coli and S. typhimurium. From primary screening, it was evident that 7,10-EODA was adjuvant with some non β-lactam antibiotics (> 70% increase in ZOI). From the checkerboard assays (Table 3), 7,10-EODA exhibited synergy (FICI range, 0.24–0.37) with streptomycin in 83% of the strains. In contrast 7,10-EODA with chlorpromazine (FICI range, 0.64–1.25) and ciprofloxacin (FICI range, 0.74–1.25) exhibited weak synergy or additive effect in most of the S. aureus strains tested.

Table 2.

In vitro inhibitory activity of 7,10-EODA in combination with β-lactam antibiotics against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

| Straina | Oxacillin | Ampicillin | Penicillin | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (µg/ml) | FIC index | MIC (µg/ml) | FIC index | MIC (µg/ml) | FIC index | ||||||||||

| Ab | B | C | b | c | A | B | C | b | c | A | B | C | b | c | |

| 01ST001 | 62.5 | 15.6 | 3.90 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 1000 | 125 | 62.5 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 500 | 250 | 31.2 | 0.74 | 0.31 |

| 01ST093 | 2000 | 1000 | 125 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 31.2 | 15.6 | 3.90 | 0.62 | 0.37 | 15.6 | 7.81 | 1.95 | 0.62 | 0.37 |

| 01ST165 | 31.2 | 7.81 | 3.90 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 2000 | 500 | 7.81 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 1000 | 500 | 31.2 | 0.62 | 0.28 |

| 02ST085 | 250 | 125 | 7.81 | 0.62 | 0.15 | 1000 | 500 | 62.5 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 125 | 31.2 | 7.81 | 0.37 | 0.31 |

| 02ST136 | 62.5 | 15.6 | 3.90 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 1000 | 125 | 15.6 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 1000 | 250 | 62.5 | 0.37 | 0.31 |

| 03ST120 | 250 | 125 | 31.2 | 0.62 | 0.37 | 250 | 31.2 | 7.81 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 62.5 | 15.6 | 3.91 | 0.37 | 0.31 |

| ATCC 8739 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.31 | 1.25 | 0.72 | 125 | 125 | 62.5 | 1.25 | 1.00 |

| KCTC 2515 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 1.25 | 1.50 |

aThe MIC of 7,10-EODA against MRSA strains was 125 µg/ml and against Gram negative strains (8739 and 2515) was > 500 µg/ml

bA, without 7,10-EODA. B to, C and b to c, 7,10-EODA at 15.6 and 31.2 µg/ml for MRSA strains, and 125 and 250 μg/ml for Gram negative strains, respectively

Table 3.

In vitro synergy of 7,10-EODA in combination with non β-lactam antibiotics against clinical strains of S. aureus

| Straina | MIC of antibiotics (µg/ml) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomycin | FICI | Chlorpromazine | FICI | Ciprofloxacin | FICI | ||||||||||

| Ab | B | C | b | c | A | B | C | b | c | A | B | C | b | c | |

| 01ST001 | 62.5 | 15.6 | 7.81 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 125 | 31.2 | 15.6 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 3.90 | 1.24 | 0.49 |

| 01ST018 | 2000 | 1000 | 250 | 0.67 | 0.37 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 31.2 | 1.12 | 0.49 | 7.80 | 7.80 | 3.90 | 1.12 | 0.74 |

| 01ST093 | 31.2 | 7.81 | 1.97 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 250 | 125 | 31.2 | 0.62 | 0.39 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 0.31 | 1.12 | 0.49 |

| 29213 | 6.25 | 1.56 | 0.78 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 31.2 | 7.81 | 15.6 | 0.37 | 0.64 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 1.12 | 0.74 |

| SA1199 | 6.25 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 31.2 | 1.12 | 0.74 | 1.95 | 1.95 | 1.95 | 1.24 | 1.24 |

| SA1199B | 7.81 | 7.81 | 3.90 | 1.12 | 0.74 | 125 | 62.5 | 125 | 0.64 | 1.24 | 7.81 | 7.81 | 3.90 | 1.24 | 0.74 |

Boldface represents potential synergy (FIC index <1.0)

a001, 018 and 093 are clinical MRSA. SA 1199 and SA 1199 B, and ATCC 29213 are methicillin-sensitive S. aureus reference strain

bA, without 7,10-EODA. B to, C and b to c, 7,10-EODA at 15.6 and 31.2 µg/ml, respectively. The MIC of 7,10-EODA is 125 µg/ml

Time Kill Kinetics

7,10-EODA/β-lactam combinations showing synergy interaction in checkerboard assay were confirmed by time kill kinetics. The time kill kinetics of 7, 10-EODA-oxacillin, 7,10-EODA-ampicillin, and 7,10-EODA-penicillin combination against MDRSA 01ST001 are illustrated in Fig. 3a–c. In all cases, the untreated controls quickly reached the stationary phase (9.2–9.5 log c.f.u/ml) with in 6 h and remained stable thereafter during 24 h. 7,10-EODA at 15.6 µg/ml did not affect the growth of MDRSA 01ST001. 7,10-EODA (31.2 µg/ml), oxacillin (3.9 µg/ml, 1/16MIC), and ampicillin (62.5 µg) all had temporary growth inhibition by 3 h but the growth seems to be comparable to controls during 24 h incubation. Combination of 7,10-EODA (15.6 µg/ml) with oxacillin (3.9 µg/ml, 1/16MIC), ampicillin (62.5 µg/ml, 1/16MIC), and penicillin (31.2 µg/ml) exhibited additive effect (Range, 1.2–2.6 log reduction). Interestingly, combinations of 7,10-EODA/oxacillin (31.2 µg/ml/3.9 µg/ml), 7,10-EODA/ampicillin (31.2 µg/ml/62.5 µg/ml), and 7,10-EODA/penicillin (31.2 µg/ml/31.2 µg/ml) yielded 3.88, 3.89, and 4.27 log reductions suggesting a bactericidal interaction.

Fig. 3.

Time-kill kinetics for MDRSA 01ST001 in presence of individual and combinations of β-lactam antibiotics. Cultures were incubated with a 3.9 µg/ml of oxacillin; b 62.5 µg/ml of ampicillin; c 31.2 µg/ml of penicillin in combination with 7,10-EODA at 15.6 µg/ml (E1) and 31.2 µg/ml (E2). Controls with DMSO served as blank. Samples treated with only 7,10-EODA and antibiotics served as controls. Samples were obtained at various time points and plated for viable counts. The results are the mean ± SD (n = 4)

7,10-EODA Causes Membrane Integrity Loss in MDRSA 01ST001

From fluorimetric assay (Fig. 4), it was evident that cells treated with DMSO exhibited a small increase in RFF value (1.26 ± 0.11) over 30 min. A significant increase in the RFF value of EtBr (4.96 and 4.58 folds, p < 0.001) was evident in presence of 15.6 and 31.2 µg/ml of 7,10-EODA, respectively. Positive control (CCCP, 5 µM) exhibited a 2 fold increase in RFF of EtBr (p < 0.05). Further, microscopic visualization of MDRSA 01ST001 cells (Fig. 5) revealed that cells treated with increasing concentration of 7,10-EODA found to contained increased concentration of propidium iodide (PI).

Fig. 4.

Effects of 7,10-EODA on the fluorescent intensity of EtBr incubated with clinical isolate of MDRSA 01ST001 at 15.6 and 31.2 µg/ml. CCCP served as positive control. The results are the mean ± SD of two separate experiments with triplicates (n = 6). Student’s t test: ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 compared with controls

Fig. 5.

Confocal microscopic visualization of 7,10-EODA induced influx of propidium iodide (PI) in MDRSA 01ST001. DAPI was used as a counter stain. Each experiment was repeated two times with 3 replicates and representative image were presented. (Scale bar: 10 µm)

Bocillin-FL Binding Study

Using fluorescent penicillin analog, bocillin-FL, the interaction between penicillin binding proteins and β-lactam antibiotic was studied. It was found that cells grown in the presence of 7,10-EODA (31.2 µg/ml) had moderate, yet statistically significant binding of (31.7%, p < 0.05) of Bocillin-FL (Fig. 6). However, 7,10-EODA (15.6–31.2 µg/ml) did not enhance the binding of Bocillin-FL in the case of ATCC 29213 (Fig. S2).

Fig. 6.

Biocillin-FL binding in Staphylococcus aureus in presence of 7,10-EODA. a Uptake of Bocillin-FL by MDRSA01ST001 and ATCC 29213. Each experiment was repeated 3 times with four replicates (n = 12). Student’s t test: ** p < 0.01 in comparison with controls. b Confocal microscopy visualization of bocillin-FL uptake in MDRSA01ST001. Each experiment was performed two times with three replicates (n = 6) and representative images were presented

7,10-EODA May be a Potential Inhibitor of Efflux Pump Activity in MDRSA 01ST001

We studied the reversal of MIC of EtBr by 7,10-EODA in MDRSA01ST001, SA1199B (Nor A over expressing), and SA1199 (wild type) strains. From the checkerboard assay (Table 4), it is evident that the MIC of EtBr (25 µg/ml) was reduced by 8, 4, and 4 folds in presence of 31.2 µg/ml of 7,10-EODA against MDRSA 01ST001, SA 1199B, and SA1199, respectively and this effect was comparable with CCCP, an ionophore, which at 6.25 µg/ml, reduced the MIC of EtBr by 8 fold against test strains. Verapamil reduced the MIC of EtBr by 4–16 folds against the tested strains.

Table 4.

Effect of 7,10-EODA on antibiotic delivery in S. aureus with efflux pump activity

| Drug (µg/ml) | MIC of EtBr (µg/ml)/(fold reduction) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 01ST001 | SA1199B | SA1199 | |

| Controls | 25 | 25 | 6.25 |

| 7,10-EODA | |||

| 15.6 | 6.25/(4) | 12.5/(2) | 3.12/(2) |

| 31.2 | 3.12/(8) | 6.25/(4) | 1.56/(4) |

| CCCP | |||

| 3.95 | 6.25/(4) | 12.5/(2) | 1.56/(4) |

| 7.81 | 3.12/(8) | 3.12/(8) | 0.78/(8) |

| Verapamil | |||

| 62.5 | 3.12/(8) | 6.25/(4) | 3.12/(2) |

| 125 | 1.56/(16) | 1.56/(16) | 1.56/(4) |

Boldface represents increased accumulation of ethidium bromide in presence of efflux inhibitors

Discussion

MRSA has become resistant to vancomycin, teicoplanin, daptomycin, and linezolid [3]. Further, pharmaceutical companies with diminished profits, reduced its research on novel antibiotic discovery. Hence a clinical demand exists for safe non-antibiotic agents to against MRSA. The antimicrobial and virulence inhibitory role of 7,10-EODA was reported [14]. In light of these facts, the present study evaluated the adjuvant action of 7,10-EODA with conventional antibiotics against MDRSA 01ST001. 7,10-EODA at 125 µg/ml is bactericidal against many S. aurues strains including MRSA. However, In vitro synergy was observed with 7,10-EODA and β-lactam antibiotics against clinical isolates of MRSA strains with MDR phenotype. Time-kill kinetics revealed that the combinations of 7,10-EODA and β-lactams are bactericidal against MDRSA 01ST001. However, to the best our knowledge, we have described for the first time the β- lactam adjuvant potential of 7,10-EODA against MDRSA.

In general penicillin binding proteins (PBP2a) and β-lactamases confer β-lactam resistance in MDRSA. 7,10-EODA due to lipophilicity can accumulate and quickly alter the membrane integrity of MDRSA01ST001 in a non lethal manner. In contrast, membrane integrity loss by several toxic lipids was lethal against S. aureus [19]. Considering the fact that membrane integrity is important for cell wall synthesis and transport [20], we propose that mechanism of β-lactam synergy by 7,10-EODA is a dual step process with a fast acting membrane damage step followed by a slow interference with PBP/2a activity in MDRSA/MRSA. Therefore, 7,10-EODA and β-lactams combination would sequentially impact membrane integrity as well as cell wall biosynthesis. In support of our hypothesis, 7,10-EODA enhanced Bocillin-FL binding to PBPs in MDRSA01ST001 and did not synergize β-lactams in MSSA. Earlier a fatty acid derivative (HAMLET) potentiated β-lactam activity against wide range of pathogens by virtue of membrane disruption [21].

Among the non β-lactams tested for synergy 7,10-EODA/streptomycin combination was the more potent in terms of FIC index against MRSA and MSSA. Besides being membrane active, lipids potentiate aminoglycoside activity by facilitating its uptake and inhibition of protein synthesis in S. aurues. These two mechanisms might have simultaneously acted to result in strong synergy observed with 7,10-EODA/streptomycin combination. These results are consistent with aminoglycoside potentiating activity of glyceryl monolaurate, tridecan-1-ol against S. aureus strains [22, 23]. In our study, chlorpromazine/7,10-EODA combination resulted in synergy against MRSA strains. We speculate that such combination might work sequentially on the β-lactam resistance factors. In support of our observation, chlorpromazine was shown to reduce mec A and bla genes expression in MRSA [24]. MRSA resistance to fluoroquinolones may be due to the activation of multidrug transporters such as nor A proteins [25]. 7,10-EODA/ciprofloxacin combination elicited a weak synergy against MRSA/MSSA and this effect was attributed to the efflux inhibitory potential of 7,10-EODA in MDRSA. MDRSA01ST001 is an efflux phenotype (data not shown) and we further shown that 7,10-EODA inhibited EtBr efflux in MDRSA 01ST001 and SA1199B (Nor A over expressing) strains. These results are consistent with previous studies pertaining to the efflux inhibitory activity of linoleic and oleic acids from purslane (32–64 µg/ml) potentiating erythromycin activity against MRSA [26].

The results of the present study suggested that 7,10-EODA has potential to synergize β-lactam antibiotics against clinical MRSA with MDR phenotype. The benefit of using 7,10-EODA as adjuvant is twofold, as it adds to the antimicrobial library and extends the use of β-lactam antibiotics. The concentration of 7,10-EODA used in this study can be clinically achievable. Further, the benefit of using anti-oxidant molecule, 7,10-EODA as adjuvant is twofold, as it acts as a preservative in topical preparations as well as repurpose the use of β-lactam in patients with chronic secondary infections or sepsis. 7,10-EODA is a new chemical entity, therefore thorough investigation on the in vivo efficacy and molecular mechanism of antibiotic synergy is required.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and future planning (2015R1A2A2A01005656).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12088-017-0680-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Gould IM, David MZ, Esposito S, Garau J, Lina G, Mazzie T, Peters G. New insights into meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) pathogenesis, treatment and resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.David MZ, Daum RS. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:616–687. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundmann H, Aires-de-sousa M, Boyce J, Tiemersma E. Emergence and resurgence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a public-health threat. Lancet. 2006;368:874–885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Townes JM, Craig AS, Zell ER, Fosheim GE, McDougal LK, Carey RB, Fridkin SK, Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) MRSA Investigators Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown D. Antibiotic resistance breakers can repurpose drugs to fill the antibiotic discovery void. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:821–832. doi: 10.1038/nrd4675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman M. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria: prevalence in food and inactivation by food compatible compounds and plant extracts. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:3805–3822. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b00778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desbios AP, Smith VJ. Antibacterial free fatty acids: activities, mechanisms of action and biotechnological potential. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;85:1629–1642. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Speiteller G. Furan fatty acids: occurrence, synthesis, and reactions. Are furan fatty acids responsible for cardioprotective effect of fish diet? Lipids. 2005;40:755–771. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1438-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishii K, Okajima H, Okada Y, Watanabe H. Effects of phosphatidylcholines containing furan fatty acid on oxidation in multi lamellar liposomes. Chem Pharm Bull. 1989;37:1396–1398. doi: 10.1248/cpb.37.1396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teixeira A, Cox RC, Egmond MR. Furan fatty acids efficiently rescue brain cells from cell death induced by oxidative stress. Food Funct. 2013;4:1209–1215. doi: 10.1039/c3fo60094g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wakimoto T, Kondo H, Nii H, Kimura K, Egami Y, Oka Y, Yoshida M, Kida E, Ye Y, Akahoshi S, Asakawa T, Matsumura K, Ishida H, Nukaya H, Tsuji K, Kan T, Abe I. Furan fatty acid as an anti-inflammatory component from the green lipped mussel Perna canaliculus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:17533–17537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110577108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knechtle P, Diefenbacher M, Greve KB, Brianza F, Folly C, Heider H, Lone MA, Long L, Meyer JP, Roussel P, Ghannoum MA, Schneiter R, Sorensen AS. The natural diyene-furan fatty acid EV-086 is an inhibitor of fungal delta-9 fatty acid desaturation with efficacy in a model of skin detmatophytosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:1455–1466. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01443-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellamar JB, Song KS, Kim HR. One-step production of a biologically active novel furan fatty acid from 7,10-dihydroxy-8(E)-octadecenoic acid. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:8175–8179. doi: 10.1021/jf2015683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dasagrandhi C, Ellamar JB, Kim YS, Kim HR. Antimicrobial activity of a novel furan fatty acid, 7,10-epoxyoctadeca-7,9-dienoic acid against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2016;25:1671–1675. doi: 10.1007/s10068-016-0257-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinical and Laboratory and Standards Institute . Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standards. CLSI document M07-A10. 10. Pennsylvania: Clinical and Laboratory and Standards Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nair DR, Monteiro JM, Memmi G, Thanassi J, Pucci M, Schwartzman J, Pinho MG, Cheung AL. Characterization of a novel small molecule that potentiates β-lactam activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1876–1885. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04164-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cabral V, Luo X, Junqueira E, Costa SS, Mulhovo S, Duarte A, Couto I, Viveiros M, Ferreira MJ. Enhancing activity of antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus: Zanthoxylum capense constituents and derivatives. Phytomedicine. 2015;25:769–772. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cottagnoud P, Cottagnoud M, Tauber MG. Vancomycin acts synergistically with gentamicin against penicillin-resistant pneumococci by increasing the intracellular penetration of gentamicin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:144–147. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.144-147.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsons JB, Yao J, Frank MW, Jackson P, Rock CO. Membrane disruption by antimicrobial fatty acids releases low molecular weight proteins from Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:5294–5530. doi: 10.1128/JB.00743-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernal P, Lemaire S, Pinho MG, Mobashery S, Hinds J, Taylor PW. Insertion of epicatechin gallate into the cytoplasmic membrane of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disrupt penicillin-binding protein (PBP) 2a mediated β-lactam resistance by delocalizing PBP2. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24055–24065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.114793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marks LR, Clement EA, Hakansson AP. Sensitization of Staphylococcus aureus to methicillin and other antibiotics in vitro and in vivo in the presence of HAMLET. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e63158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hess DI, Stanley MJH, Wells CL. Antibacterial synergy of glycerol monolaurate and aminoglycosides in S. aureus biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:6970–6973. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03672-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilbertson JR, Langkamp HH, Connamacher R, Platt D. Use of lipids to potentiate the antibacterial activity of aminoglycosides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;26:306–309. doi: 10.1128/AAC.26.3.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang R, Kang OH, Seo YS, Mun SH, Zhou T, Shin DW, Kwon DY. The inhibition effect of chlorpromazine against the β-lactam resistance of MRSA. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2016;9:542–546. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalia VC, Wood TK, Kumar P. Evolution of resistance to quorum sensing inhibitors. Microb Ecol. 2014;68:13–23. doi: 10.1007/s00248-013-0316-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan BC, Han XQ, Lui SL, Wong CW, Wang TB, Cheung DW, Cheng SW, Ip M, Han SQ, Yang XS, Jolivalt C, Lau CB, Leung P, Fung KP. Combating against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-two fatty acids from Purslane (Portulaca oleracear L) exhibit synergistic effect with erythromycin. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2014;67:107–116. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.