Abstract

Introduction

Dementia is one of the major health threats to our aging society, and Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the leading cause. In Japan, ∼15% of the elderly population has dementia. The apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype and a polymorphism (rs10524523) in the translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40 (TOMM40) gene have been associated with the age of onset of AD. However, differences in allele frequencies of these markers in different ethnic populations are not well known.

Methods

Whole blood samples were collected from 300 Japanese subjects, and genomic DNA was extracted to determine APOE alleles and TOMM40 rs10524523 genotypes.

Results

Our results indicated that the APOE ε3–TOMM40′523 short haplotype is less frequent in Japanese subjects than in Caucasians, whereas the APOE ε3–TOMM40′523 long and APOE ε3–TOMM40′523 very long haplotypes are more frequent in Japanese subjects than in Caucasians. We also showed that the APOE ε4–TOMM40′523 short haplotype, which was noted to be frequently observed in African Americans, was also found in the Japanese population, although it is extremely rare in the Caucasian population.

Discussion

A biomarker risk assignment algorithm, using a combination of APOE, TOMM40′523 genotype, and age, has been developed to assign near-term risk for developing the onset of mild cognitive impairment due to AD and is being used as an enrichment tool in an ongoing delay-of-onset clinical trial. Understanding the characterization of APOE and TOMM40 allele frequencies in the Japanese population is the first step in developing a risk algorithm for AD research and clinical applications for AD prevention in Japan.

Keywords: Allele frequency, Alzheimer's disease, Apolipoprotein E (APOE), Japanese, Poly-thymine (poly-T) variants, Translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40 (TOMM40)

Highlights

-

•

Linkage between the translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40 (TOMM40′523) and apolipoprotein E (APOE) allele differs depending on the population.

-

•

The APOE ε3–TOMM40′523 short haplotype is less frequent in the Japanese population than in Caucasian ones.

-

•

The APOE ε3–TOMM40′523 long and very long haplotypes are more frequent in the Japanese population than in Caucasian ones.

1. Introduction

In developed countries, the number of dementia patients is increasing rapidly as the population ages. Therefore, identifying ways to delay or treat dementia is important from both medical and socioeconomic perspectives. In Japan, approximately 15% of the elderly population (aged ≥65 years) has dementia. The estimated number of patients with dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is approximately 4.6 million and 4.0 million, respectively (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare research group, 2012). Alzheimer's disease (AD), cerebrovascular dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies are common forms of dementia; the most common is AD, accounting for ∼40%–60% of all dementia patients.

Both genetic and environmental factors are considered to be involved in the development of AD. A number of genes have been implicated as risk factors for development of late-onset AD [1], [2]. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) is the most thoroughly studied gene among those related to AD. It is located on human chromosome 19 and is known to have three allelic variations (ε2, ε3, and ε4). Because the frequency of the ε4 allele is higher in patients with AD than in healthy controls, and the number of ε4 alleles correlates with the age of onset of AD [3], ε4 is considered to be the major genetic risk factor for AD. However, not all AD patients have the APOE ε4 allele, and not all individuals with the ε4 allele develop AD. Therefore, risk factors other than APOE ε4 have been explored extensively in recent years [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. Moreover, there is increasing evidence that the genetic risk for AD in different ethnic groups may, in part, be explained by variation in genes in addition to the APOE-epsilon alleles. For example, variation in ABCA7 has been associated with increased AD risk in African Americans [9]. Therefore, it is important to understand the genetic contribution to AD risk in the Japanese population.

Recently, variation in the gene for outer mitochondrial membrane protein, translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40 (TOMM40), has been associated with age of onset of AD in Caucasians [10], [11]. The TOMM40 gene is located on chromosome 19, adjacent to and 5′-upstream of the APOE gene. The TOMM40 gene contains poly-thymine (poly-T) repeats within intron 6, and there are genetic polymorphisms in the length of the poly-T repeat (rs10524523; 523 hereafter). Genetic analysis of Caucasians has revealed linkage disequilibrium between APOE and 523 polymorphisms. The poly-T length of either ≤19 bp (short [S]) or ≥30 bp (very long [VL]) is tightly linked with the ε3 allele, whereas poly-T length of 20–29 bp (long [L]) is associated with ε4 in Caucasians. Recently, it has been reported that 523 polymorphisms are associated with the age of onset of AD [10], [12], [13]. Accordingly, it is expected that the combination of APOE and TOMM40′523 polymorphisms can predict the risk and onset of AD more precisely.

Identification of cognitively normal individuals at high risk for developing AD symptoms may allow early medical intervention or preventive therapies. Using longitudinally collected cohorts of elderly Caucasian subjects, a biomarker risk assignment algorithm (BRAA) comprising the APOE genotype, TOMM40′523 genotype, and age of an individual was developed to predict the risk of developing MCI due to AD within the next 5 years in people aged 65–83 years [14], [15]. A clinical study (TOMMORROW; ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01931566) is being conducted to qualify the BRAA and evaluate the efficacy of pioglitazone 0.8 mg sustained release to delay the onset of MCI due to AD in high-risk subjects as determined by the BRAA. However, it is unknown if the BRAA developed for Caucasians is informative for the Japanese population.

In this article, we describe the genetic architecture of this region of chromosome 19 in a Japanese cohort as the initial step to understanding the role this region plays in AD risk in individuals of Japanese ancestry. Knowledge of the genetic factors contributing to AD risk will contribute to clinical development of effective therapeutics to ease the burden of AD.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This study consisted of clinical research to investigate the frequencies of APOE alleles and TOMM40′523 genetic polymorphisms in the Japanese population.

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the “Ethical Guidelines on Clinical Studies” [16], “Ethical Guidelines for Human Genome/Gene Analysis Research” [17], and all other applicable laws and regulations. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards at the participating study sites. All patients provided written informed consent.

2.2. Study subjects

Subjects who met all the following inclusion criteria were eligible for the study: (1) healthy men or women aged ≥20 years at the time of consent, and (2) subjects whose parents and grandparents were all self-reported native Japanese. Exclusion criteria included subjects: (1) who had already participated in this study, (2) whose relatives up to the third degree had participated in this study, (3) with poor peripheral venous access, (4) who had received whole blood transfusion ≤3 months before participation, or (5) who had received bone marrow, organ, or stem cell transfusion/transplantation.

The number of subjects in this study was expected to be 150 men and 150 women, a total of 300 subjects.

2.3. Study endpoints

The endpoints were frequencies of APOE alleles (ε2, ε3, ε4), the frequencies of TOMM40′523 alleles (S, L, VL), the frequencies of APOE genotypes (ε2/ε2, ε2/ε3, ε2/ε4, ε3/ε3, ε3/ε4, ε4/ε4), the frequencies of TOMM40′523 genotypes (S/S, S/L, S/VL, L/L, L/VL, VL/VL), the frequencies of APOE–TOMM40′523 haplotypes (ε2–S, ε2–L, ε2–VL, ε3–S, ε3–L, ε3–VL, ε4–S, ε4–L, ε4–VL), and the TOMM40′523 poly-T length.

2.4. Genetic analysis

Whole blood samples were collected for genetic analysis from subjects who met the eligibility criteria described previously. Blood samples were anonymized with unique subject identification codes at the research site, and the samples were then sent to the clinical laboratory. Genomic DNA was extracted from the blood samples at the clinical laboratory, and an aliquot of the extracted DNA was sent to the genetic laboratory (Polymorphic DNA Technologies, Inc., Alameda, CA, USA). Genotyping of APOE alleles and TOMM40′523 was performed, and the haplotype of each subject was analyzed according to the following sections.

2.4.1. APOE genotyping

There are two single-nucleotide polymorphisms located on the APOE gene, that is, rs429358 and rs7412. APOE single-nucleotide polymorphisms were determined using the extracted genomic DNA as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) templates by means of nested PCR methods and DNA sequencing.

2.4.2. TOMM40′523 poly-T genotyping and length analysis

Genotyping was performed as previously described at Polymorphic DNA Technologies (Alameda, CA, USA). For genotyping of TOMM40′523 poly-T, a variation of the PCR amplicon sequencing method was used. As described previously, nested PCRs were performed to create a purified amplicon, and it was then subjected to the Sanger sequencing reaction and processed using a capillary DNA analyzer to create electropherograms. The electropherograms were analyzed using proprietary software by Polymorphic DNA Technologies to interpret the complex A-peak pattern seen at the end of electropherograms containing TOMM40′523 poly-T genotypes. To determine the 523 poly-T length accurately, the amplified DNA was cloned into plasmids, transformed into bacteria, and the DNA was recovered and subjected to Sanger sequencing.

For genomic samples in which the phase for TOMM40′523 and APOE could not be established by genotyping alone (e.g., heterozygous genotypes for APOE or TOMM40′523, including APOE ε2/ε4 and APOE ε3/ε4), the phase was instead established through methods described previously [18]. Briefly, a 9.5 kb genomic fragment was generated by long-range PCR, cloned into plasmids, and had the DNA sequence determined by Sanger sequencing.

2.5. Caucasian clinical data sets

Data for the Caucasian population were obtained from DNA samples purchased from The Human Genetic Cell Repository at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, NJ, USA, www.coriell.org/). This biobank is sponsored by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Bethesda, MD, USA, www.nigms.nih.gov). In all cases, samples with the APOE ε3/ε3, APOE ε3/ε4, or APOE ε4/ε4 genotypes were used for this analysis. Seventy Caucasian DNA samples (140 haplotypes) were used in the analysis: 54% were female, mean age was 39 years (standard deviation [SD] = 15), and 11% of the haplotypes had an APOE ε4 allele.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of allele frequencies of APOE and TOMM40′523 between the Japanese and Caucasian populations

The proportions of TOMM40′523 allele polymorphisms associated with APOE allele types in the Japanese and Caucasian populations are shown in Table 1. When the APOE allele was ε4, the numbers of Japanese subjects for each type of 523 allele were 16 for the S (29.6%), 33 for the L (63.0%), and 4 for the VL (7.4%); the most frequent type was L. Two notable differences in haplotype frequencies between the Japanese and Caucasian cohorts are observed: with rare exceptions, only the APOE ε3/ε4–TOMM40′523 L haplotype is observed in Caucasians; however, in the Japanese cohort, the APOE ε4–TOMM40′523 S haplotype is fairly common (29.6%). The APOE ε4–TOMM40′523 VL haplotype frequency also differs between Japanese (7.4%) and Caucasian (0.0%) subjects. When the APOE allele was ε3, the numbers of Japanese subjects with each type of 523 allele were 159 for the S (31.4%), 47 for the L (9.3%), and 300 for the VL (59.3%); the most frequent APOE ε3 allele was VL. The numbers of Caucasian subjects showed a slightly different trend: the most frequent types were S (52.0%) and VL (48.0%).

Table 1.

Proportion of TOMM40′523 alleles connected to APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 chromosomes

| APOE ε4 | Japanese (N = 54), n (%) | Caucasian (N = 15), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| S | 16 (29.6) | 0 (0) |

| L | 34 (63.0) | 15 (100) |

| VL |

4 (7.4) |

0 (0) |

|

APOE ε3 |

Japanese (N = 506), n (%) |

Caucasian (N = 125), n (%) |

| S | 159 (31.4) | 65 (52.0) |

| L | 47 (9.3) | 0 (0) |

| VL | 300 (59.3) | 60 (48.0) |

Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; L, long; S, short; TOMM40, translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40; VL, very long.

3.2. TOMM40′523 alleles linked to APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 in the Japanese and Caucasian populations

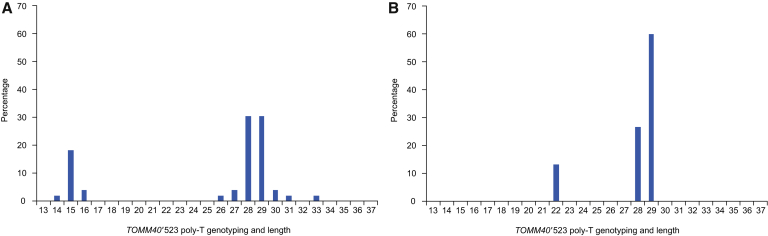

Histograms of TOMM40′523 poly-T length connected to APOE ε4 in Japanese subjects are shown in Fig. 1A, and in Caucasians in Fig. 1B. The Japanese population had peaks in the T14–16 (S) and T26–29 (L) poly-T groupings, whereas the Caucasian population had two distinct peaks in the T22 (L) and T28–29 (L) poly-T groupings.

Fig. 1.

Haplotypes of TOMM40′523 alleles connected to APOE ε4. The poly-T allele lengths are indicated in Japanese and Caucasian individuals. (A) Japanese subjects had S, L, and VL poly-T groupings at T14–16, T26–29, and T30–31/33, respectively (number of alleles = 54). (B) Caucasians had two L poly-T groupings at T22 (number of alleles = 15) and T28/29 and no S poly-T groupings. The data show that the first peak in Japanese subjects (T14–16) was slightly shorter than that in Caucasians (T22). Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; L, long; poly-T, poly-thymine; S, short; TOMM40, translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40; VL, very long.

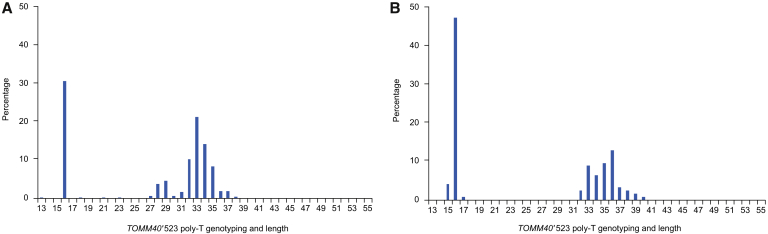

Histograms of TOMM40′523 poly-T length connected to APOE ε3 in Japanese subjects are shown in Fig. 2A, and in Caucasians in Fig. 2B. The Japanese population had peaks in the T16 (S), T28–29 (L), and T32–35 (VL) poly-T groupings. The Caucasian population had peaks in the T16 (S) and T33–36 (VL) poly-T groupings.

Fig. 2.

Haplotypes of TOMM40′523 alleles connected to APOE ε3. The poly-T allele lengths are indicated in Japanese and Caucasian individuals. (A) Japanese subjects had S, L, and VL poly-T groupings at T16, T27–29, and T30–38, respectively (number of alleles = 506). (B) Caucasians in several series had two well-characterized peaks in the S range at T15–16 and the VL range at T32–40 range (number of alleles = 125). Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; L, long; poly-T, poly-thymine; S, short; TOMM40, translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40; VL, very long.

3.3. Comparison of allele frequencies of APOE between the Japanese and the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study populations

The results of allele frequencies of APOE in the Japanese population were compared with those of the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study (HAAS) population [19] and are shown in Table 2. The HAAS comprised elderly males of Japanese ancestry residing in Hawaii [20]. The most frequently observed allele type of APOE was ε3 (86% in the Japanese group; 83% in the HAAS group), followed by ε4 (10% in the Japanese group; 11% in the HAAS group) and ε2 (5% in the Japanese group; 6% in the HAAS group), suggesting that these two populations had similar allele frequencies of APOE.

Table 2.

APOE allele frequencies

| Allele frequency | Japanese | HAAS |

|---|---|---|

| APOE ε2, n (%) | 28 (5) | 70 (6) |

| APOE ε3, n (%) | 515 (86) | 1057 (83) |

| APOE ε4, n (%) | 57 (10) | 145 (11) |

Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; HAAS, Honolulu-Asia Aging Study.

NOTE. Subject numbers: Japanese (N = 300), HAAS (N = 649).

3.4. Comparison of genotype and allele frequencies of TOMM40′523 between the Japanese and the HAAS populations

The results of genotype and allele frequencies of TOMM40′523 in the Japanese population were compared with those in the HAAS [19] and are shown in Table 3. The most frequently observed 523 genotype was S/VL (33% in the Japanese group; 36% in the HAAS group), followed by VL/VL (29% in the Japanese group, 26% in the HAAS group) and L/VL (13% in the Japanese group, 16% in the HAAS group), suggesting that these two populations had similar 523 genotypes.

Table 3.

TOMM40′523 genotype and allele frequencies

| 523 genotype | Japanese, n (%) | HAAS, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| S/S | 68 (11) | 70 (11) |

| S/VL | 198 (33) | 229 (36) |

| VL/VL | 172 (29) | 163 (26) |

| L/VL | 76 (13) | 97 (16) |

| S/L | 70 (12) | 61 (10) |

| L/L |

12 (2) |

15 (2) |

| 523 allele |

Japanese, n (%) |

HAAS, n (%) |

| S | 198 (34) | 430 (34) |

| L | 82 (14) | 188 (15) |

| VL | 304 (52) | 652 (51) |

Abbreviations: HAAS, Honolulu-Asia Aging Study; L, long; S, short; TOMM40, translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40; VL, very long.

In addition, the allele frequencies of TOMM40′523 were examined and the results showed that the most frequently observed 523 allele was VL (52% in the Japanese group, 51% in the HAAS group), followed by S (34% in the Japanese group, 34% in the HAAS group) and L (14% in the Japanese group, 15% in the HAAS group), suggesting that the two populations had similar 523 allele frequencies.

4. Discussion

Although the genetic architecture of the chromosome 19 region containing APOE and TOMM40 has been well characterized in Caucasians and African Americans [11], [18], it is less well characterized in other ethnicities. However, it is important to note that most of these studies were done in elderly cohorts at risk for AD, and it is known that the APOE-ε4 allele frequency decreases with the age of the population. For example, one large meta-analysis of populations with European ancestry reported that the frequency of the APOE-ε4 allele decreased from 17.6% to 8.3% (−9.3%) with increasing age (from age 60 to 90 years), whereas the frequency of the ε3 allele increased from 73.3% to 83.3% (+10.0%) [21]. Therefore, to compare the allele and haplotype frequencies of the APOE–TOMM40′523 variants, it was important to have a Caucasian cohort (age range 20–73 years, mean age 39 years; SD = 15; 54% female) that reflects the demographic characteristics of the Japanese cohort (age range 20–68 years, mean age 32 years; SD = 12; 50% female) and is unbiased/neutral with respect to AD risk. We therefore used well-characterized samples from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research, which were matched with these demographic characteristics. In addition to AD age of onset, the APOE locus has been associated with longevity [22], underscoring the importance of balancing for age. Although the Caucasian cohort examined in this article is relatively small (140 chromosomes compared with 300 chromosomes in the Japanese cohort), the TOMM40′523 allele and genotype frequencies are consistent with larger Caucasian cohorts of elderly subjects [11], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27].

We determined the frequencies of APOE and TOMM40′523 genetic polymorphisms and haplotypes in the Japanese population (aged 20–68 years, N = 300, 150 men and 150 women) using whole blood samples and compared the results with those of previous findings in Caucasians, as well as in the HAAS [19]. Our studies show that the specific linkage between the TOMM40′523 allele and APOE allele and the frequencies of these haplotypes differ depending on the population (e.g., Japanese, Africans, African Americans, and Caucasians). In the present study, we showed that the APOE ε3–TOMM40′523 S haplotype is less frequent in Japanese subjects than in Caucasians, whereas the APOE ε3–TOMM40′523 L and APOE ε3–TOMM40′523 VL haplotypes are more frequent in Japanese subjects than in Caucasians. We also showed that the APOE ε4–TOMM40′523 S haplotype, which was noted to be frequently observed in African Americans, was also found in the Japanese population although it is extremely rare in the Caucasian population. The TOMM40′523 L allele, considered to be associated with earlier AD onset, is connected to ɛ4 in Caucasians. On the other hand, a subset of the L alleles was found to be in cis with APOE ε3 in the Japanese population.

We previously reported that Japanese subjects appear to have a lower frequency of the APOE ε4 allele compared with Caucasians and Africans [28]. In addition, an earlier report observed ethnic differences in APOE–TOMM40 haplotype frequencies. Both African (Yorubans) and African American populations had TOMM40′523 S on the same chromosome as APOE ε4 [18].

Our study also showed that Japanese subjects appeared to have higher frequencies of the TOMM40′523 poly-T T28–29 and T32–34 alleles connected to APOE ε3 compared with Caucasians and Africans. In addition, Japanese subjects appeared to have lower frequencies of the TOMM40′523 poly-T T16 allele connected to APOE ε3 compared with Caucasians and Africans [28]. However, we did not find any extra-long alleles (T40–57), which have occasionally been observed in African and African American subjects [18].

Interestingly, the allele frequencies of APOE in the Japanese population and the HAAS population showed a similar frequency (Table 2). In addition, TOMM40′523 genotype and allele frequencies between the Japanese and HAAS populations appeared to have similar trends, although the study criteria were slightly different: dementia in an elderly (>72 years) Asian male population for the HAAS, and healthy male and female subjects aged ≥20 years for the Japanese population. These data further imply that similarity in the ethnicity of populations would provide similar APOE–TOMM40′523 haplotypes.

There is growing interest in the AD research community in intervening in the cognitive decline associated with AD earlier in the disease continuum. A number of interventional studies have been proposed to enroll subjects with normal cognition and follow them until there is evidence of cognitive decline [11]. By necessity, this type of study design puts significant requirements on identifying subjects at increased risk of cognitive decline during the study period, and a variety of biomarkers are being investigated [11], including genetic markers. Understanding the genetic architecture of APOE and TOMM40 allele frequencies in the Japanese population is the first step in developing an algorithm to use for AD research and clinical applications for AD prevention in Japan.

A recent perspective article pointed out that genetic markers have a number of important attributes that make them attractive for enrichment in prevention trials [29]. In general, genetic testing features widely available assay methods, a stable analyte measured with a simple blood sample, and offers favorable cost efficiencies.

In conclusion, we compared the allele frequencies of APOE and TOMM40′523 polymorphisms in the Japanese population, and a potential unique haplotype in the Japanese population, namely, APOE-ε4–TOMM40′523 S, was identified. The findings reported here characterize the APOE–TOMM40 haplotypes in a population of Japanese ancestry.

Research in Context.

-

1.

Systematic review: It is well accepted that genetic factors are involved in the process of dementia that is likely caused by Alzheimer's disease (AD). Previous studies have identified candidate gene polymorphisms and their associations with different types of AD. Among these genes, apolipoprotein E (APOE) allelic variation and translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40 (TOMM40) genetic polymorphisms in intron 6 have been well studied, and relevant studies were included in the background section and cited.

-

2.

Interpretation: Our findings suggest that APOE–TOMM40 rs10524523 haplotype frequency likely differs in different populations. Our data revealed the presence of the APOE-ε4–TOMM40 rs10524523 short haplotype in the Japanese population, although it has rarely been identified in Caucasians.

-

3.

Future directions: The present work demonstrates the need to investigate the genetic architecture of the chromosome 19 region to better understand the genetic risk for AD.

Acknowledgments

Mitsuharu Tanaka, of WysiWyg Co, Ltd, Japan, provided medical writing assistance on this manuscript.

This study and manuscript were supported by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Osaka, Japan. The sponsor designed the study, was involved in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing a report of findings, and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

All of the authors were employees of their affiliated institutions at the time the study was done.

References

- 1.Hollingworth P., Harold D., Sims R., Gerrish A., Lambert J.C., Carrasquillo M.M. Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:429–435. doi: 10.1038/ng.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambert J.C., Ibrahim-Verbaas C.A., Harold D., Naj A.C., Sims R., Bellenquez C. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1452–1458. doi: 10.1038/ng.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corder E.H., Saunders A.M., Strittmatter W.J., Schmechel D.E., Gaskell P.C., Small G.W. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertram L., Lange C., Mullin K., Parkinson M., Hsiao M., Hogan M.F. Genome-wide association analysis reveals putative Alzheimer's disease susceptibility loci in addition to APOE. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H., Wetten S., Li L., St Jean P.L., Upmanyu R., Surh L. Candidate single-nucleotide polymorphisms from a genome-wide association study of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:45–53. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beecham G.W., Martin E.R., Li Y.J., Slifer M.A., Gilbert J.R., Haines J.L. Genome-wide association study implicates a chromosome 12 risk locus for late-onset Alzheimer disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrasquillo M.M., Zou F., Pankratz V.S., Wilcox S.L., Ma L., Walker L.P. Genetic variation in PCDH11X is associated with susceptibility to late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:192–198. doi: 10.1038/ng.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambert J.C., Heath S., Even G., Campion D., Sleegers K., Hiltunen M. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1094–1099. doi: 10.1038/ng.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reitz C., Jun G., Naj A., Rajbhandary R., Vardarajan B.N., Wang L.S. Variants in the ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCA7), apolipoprotein E ε4,and the risk of late-onset Alzheimer disease in African Americans. JAMA. 2013;309:1483–1492. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roses A.D., Lutz M.W., Amrine-Madsen H., Saunders A.M., Crenshaw D.G., Sundseth S.S. A TOMM40 variable-length polymorphism predicts the age of late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacogenomics J. 2010;10:375–384. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crenshaw D.G., Gottschalk W.K., Lutz M.W., Grossman I., Saunders A.M., Burke J.R. Using genetics to enable studies on the prevention of Alzheimer's disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93:177–185. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roses A.D. An inherited variable poly-T repeat genotype in TOMM40 in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:536–541. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roses A.D., Lutz M.W., Crenshaw D.G., Grossman I., Saunders A.M., Gottschalk W.K. TOMM40 and APOE: Requirements for replication studies of association with age of disease onset and enrichment of a clinical trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lutz M.W., Sundseth S.S., Burns D.K., Saunders A.M., Hayden K.M., Burke J.R. A Genetics-based Biomarker Risk Algorithm for Predicting Risk of Alzheimer's Disease. Alzheimers Dement (N.Y.) 2016;2:30–44. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roses A.D., Saunders A.M., Lutz M.W., Zhang N., Hariri A.R., Asin K.E. New applications of disease genetics and pharmacogenetics to drug development. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2014;14:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Studies. Ministerial Notification No. 415 of MHLW, July 31, 2008.

- 17.Ethical Guidelines for Human Genome/Gene Analysis Research. Ministerial Notification No. 1 of MEXT, MHLW and METI, February 8, 2013.

- 18.Roses A.D., Lutz M.W., Saunders A.M., Goldgaber D., Saul R., Sundseth S.S. African-American TOMM40'523-APOE haplotypes are admixture of West African and Caucasian alleles. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:592–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lutz MW, Goldgaber D, Burns DK, Saunders AM, White LR, Roses AD. Genetic analysis of TOMM40 and APOE for the onset of dementia in the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Poster presented at: Annual meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics; October 22-26, 2013; Boston, MA, USA.

- 20.Gelber R.P., Launer L.J., White L.R. The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study: epidemiologic and neuropathologic research on cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:664–672. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKay G.J., Silvestri G., Chakravarthy U., Dasari S., Fritsche L.G., Weber B.H. Variations in apolipoprotein E frequency with age in a pooled analysis of a large group of older people. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1357–1364. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garatachea N., Emanuele E., Calero M., Fuku N., Arai Y., Abe Y. ApoE gene and exceptional longevity: Insights from three independent cohorts. Exp Gerontol. 2014;53:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caselli R.J., Dueck A.C., Huentelman M.J., Lutz M.W., Saunders A.M., Reiman E.M. Longitudinal modeling of cognitive aging and the TOMM40 effect. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayden K.M., McEvoy J.M., Linnertz C., Attix D., Kuchibhatla M., Saunders A.M. A homopolymer polymorphism in the TOMM40 gene contributes to cognitive performance in aging. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jun G., Vardarajan B.N., Buros J., Yu C.E., Hawk M.V., Dombroski B.A. Comprehensive search for Alzheimer disease susceptibility loci in the APOE region. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:1270–1279. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linnertz C., Saunders A.M., Lutz M.W., Crenshaw D.M., Grossman I., Burns D.K. Characterization of the poly-T variant in the TOMM40 gene in diverse populations. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenbaum L., Springer R.R., Lutz M.W., Heymann A., Lubitz I., Cooper I. The TOMM40 poly-T rs10524523 variant is associated with cognitive performance among non-demented elderly with type 2 diabetes. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:1492–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nonomura H, Nishimura A, Tanaka S, Yoshida M, Maruyama Y, Aritomi Y, et al. Characterization of APOE and TOMM40 allele frequencies in a Japanese population. Poster presented at: Annual meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics; October 6-10, 2015; Baltimore, MD, USA.

- 29.Breitner J.C.S. How can we really improve screening methods for AD prevention trials? Alzheimers Dement (N.Y.) 2016;2:45–47. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]