SUMMARY

Coffin-Siris Syndrome (CSS) is an intellectual disability disorder caused by mutation of components of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex. We describe the evolution of the phenotypic features for a male patient with CSS from birth to age 7 years and 9 months and by review of reported CSS patients, we expand the phenotype to include neonatal and infantile hypertonia and upper airway obstruction. The propositus had a novel de novo heterozygous missense mutation in exon 17 of SMARCA4 (NM_001128849.1:c.2434C>T (NP_001122321.1:p.Leu812Phe)). This is the first reported mutation within motif Ia of the SMARCA4 SNF2 domain. In summary, SMARCA4-associated CSS is a pleiotropic disorder in which the pathognomic clinical features evolve and for which the few reported individuals do not demonstrate a clear genotype-phenotype correlation.

Keywords: chromatin remodeling, mental retardation, scoliosis, expressivity, choanal stenosis

INTRODUCTION

CSS is caused by mutations in SMARCB1, SMARCA4, SMARCE1, ARID1A and ARID1B [Schrier Vergano et al. 2013; Tsurusaki et al. 2012]. Each encodes a component of the SWI/SNF complex, which modulates eukaryotic gene expression and DNA repair via nucleosome remodeling [Park et al. 2006; Sudarsanam and Winston 2000 ]. In vitro studies have shown that the SWI/SNF complex disrupts nucleosome structure at promoter sites to allow the binding of transcription factors [Kingston et al. 1996; Romero and Sanchez-Cespedes 2013].

By modulating or buffering gene expression, the SWI/SNF complex contributes to cellular differentiation. Formation of an organism from a single zygote is achieved by stepwise changes in gene expression throughout development and occurs in response to cell autonomous and cell non-autonomous mechanisms [Bernstein et al. 2012; Meissner et al. 2008; Mikkelsen et al. 2007]. The loss of functional SWI/SNF will therefore alter modulation of gene expression and predispose to pathological gene expression changes and consequently the pleiotropic manifestations of CSS [Raj et al. 2010].

Besides CSS, mutations of the SWI/SNF complex are also associated with cancer and Nicolaides-Baraitser Syndrome (NBS) [Santen et al. 2012]. NBS arises from mutations in SMARCA2, which encodes another SWI/SNF complex component. Although characterized by facial features and developmental delay similar to CSS, individuals with NBS can be distinguished by the absence of hypoplastic fifth fingernails and distal phalanges and by prominent finger joints, sparse hair and more frequent internal organ malformations [Sousa et al. 2009].

The genotype-phenotype correlation for the broad spectrum of features and the different disorders associated with dysfunction of the SWI/SNF complex are incompletely understood. We review therefore the reported phenotypic characteristics of CSS and expand the phenotypic spectrum to include infantile hypertonia, vocal cord paralysis, and upper airway obstruction for individuals with mutations of SMARCA4.

CLINICAL REPORT

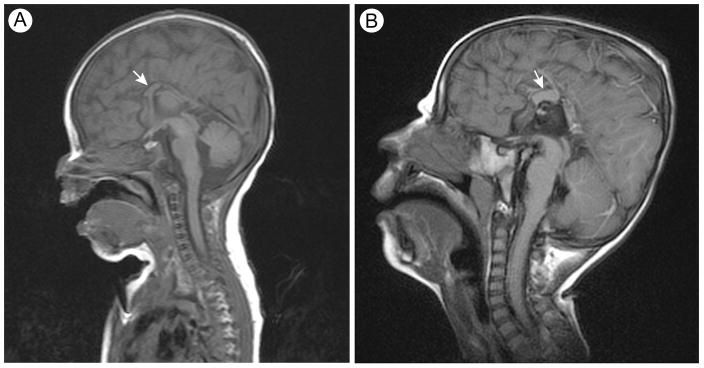

Following an uncomplicated pregnancy, the propositus was born at 41 weeks of gestation to a non-consanguineous couple of Northern European ancestry. There was no family history of intellectual disability or congenital malformations. He had a birth weight of 3.06 kg (20th centile), length of 50.5 cm (58th centile) and head circumference of 34 cm (19th centile). He had respiratory distress and required mechanical ventilation for the first few days of life. At 2 days of age, microlaryngobronchoscopy and nasolaryngoscopy identified laryngomalacia, a shortened left aryepiglottic fold and vocal cords fixed in the abducted position; reevaluation at 21 days revealed vocal cord granulomas, laryngeal erythema and edema and mobile vocal cords. He also had several dysmorphic features (Fig. 1) including short palpebral fissures, blepharophimosis, micrognathia, short midface with malar hypoplasia, deviated nasal septum, cryptorchidism, fisting of the right hand, left knee contracture, distal fifth finger and toe phalanx hypoplasia, long broad toes and hypoplasia of all toenails. Additional findings included an absent left brainstem auditory evoked response (BAER) and partial agenesis of the corpus callosum but no other brain malformations (Fig. 2).

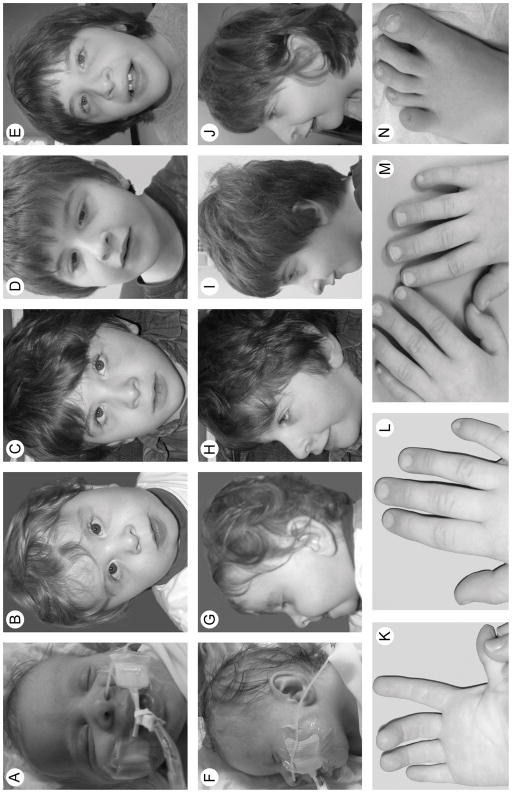

FIG. 1.

Clinical photographs of the propositus from birth to age 7 years and 9 months. Frontal and profile photographs from birth (A, F), 1 year (B, G), 5 years (C, H), 6 years (D, I), and 7 years (E, J) show the evolution of CSS-associated features. Anterior and posterior views of the hands at age 4 years 2 months (K, L) and a posterior view at age 6 years 8 months (M) show the distal fingers and hypoplastic fingernails. Photograph of the propositus’ left foot at age 7 years and 9 months (N) shows the hypoplastic toenails.

FIG. 2.

T1 weighted brain MRI images of the propositus showing the partial agenesis of the corpus callosum (arrows). Images are from scans performed at birth (A) and at age 3 years (B).

During the first year of life, the propositus manifested global developmental delay (GDD) and multiple medical problems. These problems included gastroesphageal reflux, uncoordinated swallowing, continued upper airway obstruction, laryngomalacia, muscular hypertonia with fisting of the hands and scissoring of the legs, growth restriction treated with gastrostomy tube (G-tube) feeding, hearing loss and right cryptorchidism. When examined at 12 months of age, his height, weight and head circumference were 71.1 cm (5th centile), 9.1 kg (13th centile), and 43.5 cm (1st centile) respectively. Besides microcephaly and hypertonic posturing, his dysmorphisms included brachycephaly, plagiocephaly, frontal bossing with bitemporal narrowing, bilateral supraorbital ridge hypoplasia, malar hypoplasia, short palpebral fissures, mild alar hypoplasia, a broad nasal bridge with anteverted nares, low-set and posteriorly rotated ears, a bifid uvula, prominent lower lip, ankyloglossia, hypoplastic nails and distal phalanges, particularly of the 5th digits and 5th finger clinodactyly.

During the second year of life, he had an adenoidectomy and tonsillectomy to reduce his airway obstruction and orchiopexy for his cryptorchidism. Despite these interventions and gradual improvement of his gastroesophageal reflux, he continued to have multiple problems including increasing central hypotonia and convex right thoracic scoliosis; the latter was treated with Risser serial casting after bracing failed. On examination at 2 years, he had a weight of 11.6 kg (20th centile), height of 81.3 cm (7th centile), and a head circumference of 45 cm (<1st centile). Additional dysmorphic features included a high arched palate and a mild pectus excavatum. His neurological examination was notable for the ability to sit and pull to a standing position.

Over the next two years, he had a z-plasty for his ankyloglossia and manifested fragmented sleeping patterns, strabismus, laryngomalacia and staring spells. Seizures were ruled out. On examination at 4 years and 2 months, his height, weight and head circumference were 96.43 cm (5th centile), 15 kg (19th centile), and 47 cm (<1st centile) respectively. Additional dysmorphic features included prominent eyebrows, a short forehead, a low posterior hairline and prominent pads on all fingers. His neurological evaluation was remarkable for distal spasticity with central hypotonia, brisk deep tendon reflexes, and a wide-based unsteady gait.

Due to the worsening of his scoliosis, the propositus had spinal rods inserted at the age of 6 years. He remains closely monitored for this.

The propositus was re-evaluated at the age of 6 years and 8 months. His weight, height and head circumference were 21.7 kg (43rd centile), 106.5 cm (1st centile) and 48 cm (<1st centile) respectively. His dysmorphic features were unchanged; he had no new health problems.

His fifth and most recent evaluation at age 7 years and 9 months revealed the presence of all previously stated dysmorphic features and health issues with continued slow and steady developmental progress. His weight, height and head circumference were 24 kg (40th centile), 112.5 cm (1st centile) and 48.75 cm (1st centile) respectively.

The propositus underwent extensive testing that was not diagnostic of his underlying disorder. He had a cardiac echocardiogram that showed normal cardiac anatomy and function, a normal abdominal ultrasound and hand and wrist radiographs showing hypoplasia of the 5th distal phalanx and normal bone age. Genetic testing revealed a normal male karyotype (46, XY; 450–500 band resolution), absence of deletions or duplications of 22q.11.2 or subtelomeric regions detectable by FISH. Microarray (CGH) analysis did not detect any abnormal copy number variants (SignatureChipOS; hg18 assembly). He had normal transferrin iso-electric focusing and SNRPN methylation.

MOLECULAR ANALYSES

Based on his features and negative testing, the diagnosis of CSS was first entertained when the propositus was age 4 years. This diagnosis remained contentious though because of the prominent unassociated features of neonatal and infantile hypertonia, vocal cord paralysis, and upper airway obstruction (Table I and Supplementary Table III).

Table I.

Phenotypic comparison of the propositus to other CSS patients with SMARCA4 mutations¶

| Patient | Propositus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Feature | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Age (years) | 18 | 20 | 9 | 11 | 16 | 4 | 8 | 7.75 |

| Sex | M | M | M | M | F | M | F | M |

| Mutation (NP_001122321.1) | p.Lys546del | p.Thr859Met | p.Arg885Cys | p.Leu921Phe | p.Met1011Thr | p.Arg1157Gly | p.Arg885His | p.Leu812Phe |

| SNF2 domain affected | outside of SNF2 domain | Ia–II linker | Motif II/IIa | Motif III | III–IV linker | Motif V | Motif II/IIa | Motif Ia |

| Growth | ||||||||

| Birth weight (SD) | −1.77 | −2.2 | −1.2 | −1.7 | −1.0 | −1.1 | −2.6 | −1.5 |

| Birth length (SD) | NR | NR | −0.9 | −1.6 | −1.9 | −2.3 | −2.7 | −0.9 |

| Birth OFC (SD) | NR | NR | −0.9 | −0.6 | +0.1 | −1.3 | −3.9 | −1.6 |

| Weight (SD)* | NR | −0.2 | −1.5 | −1.8 | −1.9 | −3.0 | −1.9 | −0.2 |

| Height (SD)* | −1.8 | −2.6 | −3.2 | −3.1 | −1.9 | −3.4 | −1.8 | −2.6 |

| OFC (SD)* | −2.3 | −3.8 | −3.6 | −2.9 | −2.3 | −2.7 | −3.0 | −2.6 |

| Psychomotor | ||||||||

| Developmental delay/intellectual disability | Mild | Severe | Severe | Severe | Severe | Severe | Moderate | Severe |

| Speech delay | Mild | SW | NW | NW | SC | NW | Mild | NW |

| Seizures | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Hypotonia | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| Autistic features/behavioral abnormalities | NR | H, Imp | ASD (H, HST, Ob, SHB) | − | RB | NR | H | RB |

| Brain anomaly | NR | NR | HCC,HCV | NR | NR | HCC | − | HCC |

| Craniofacial | ||||||||

| Sparse hair | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| Thick eyebrows | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Thick eyelashes | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ptosis | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| Abnormal ears | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Nasal bridge | Narrow | Narrow | Normal | Flat | Flat | Flat | Flat | Narrow |

| Thick, anteverted alae nasi | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Wide mouth | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| Philtrum | Short | Short | Short | NR | Short | NR | Short | NR |

| Upper lip vermilion | Everted | Everted | Everted | Thin | Everted | Normal | NR | Thin |

| Thick lower lip vermilion | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Palatal abnormality | SCP | HP | CP | HP | HP | CP | HP | HP |

| Skeletal-limb | ||||||||

| Hypoplastic/absent fifth finger/toe | Fr | Fr/T | T | Fr/T | Fr/T | Fr/T | T | Fr/T |

| Hypoplastic/absent nail (fifth finger/toe) | Fr | Fr/T | T | Fr/T | Fr/T | Fr/T | T | Fr/T |

| Hypoplastic/absent nail (other fingers/toes) | NR | Fr/T | T | Fr/T | Fr/T | Fr/T | − | Fr/T |

| Prominent interphalangeal joins | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Prominent distal phalanges | − | + | + | + | + | − | NR | − |

| Scoiosis/spinal abnormalities | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Joint laxity | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| Others | ||||||||

| Hirsutism | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Congenital heart defects | − | − | − | VtSD,PDA | − | MA,PA,SRV,AtSD,PDA | + | − |

| Genitourinary defects | − | NR | Crp | − | − | Crp | − | Crp |

| Gastrointestinal abnormalities | NR | GO | C | DU | C | GR | GR | GR |

| Inguinal (I)/umbilical (U) hernia | − | I | − | I | − | Om | I/U | − |

| Sucking difficulty | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Feeding difficulty | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hearing impairment | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| Visual impairment | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| Recurrent infections | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; AtSD, atrial septal defect; C, constipation; CP, cleft palate; Crp, cryptorchidism; DU, duodenal ulcer; F, female; Fr, finger; GO, gastric outlet obstruction; GR, gastroesophageal reflux; H, hyperactivity; HCC, hypoplastic corpus callosum; HCV, hypoplastic cerebellar vermis; HP, high palate; HST, hypersensitivity; I, inguinal; Imp, impulsiveness; M, male; MA, mitral atresia; NR, not reported; NW, no words; Ob, obsession; OFC, occipital-frontal circumference; Om, omphalocele; PA, pulmonary atresia; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; RB, repetitive behavior; SC, simple conversation; SCP, submucosal cleft palate; SD, standard deviation; SHB, self-harming behavior; SRV, single right ventricle; SW, several words; T, toe; VtSD, ventricular septal defect

Excepting the propositus, all patients with SMARCA4 mutations included in this table were reported by [Kosho et al. 2013]

Standard deviation (SD) of the respective growth parameter recorded for individual at the age he or she was reported.

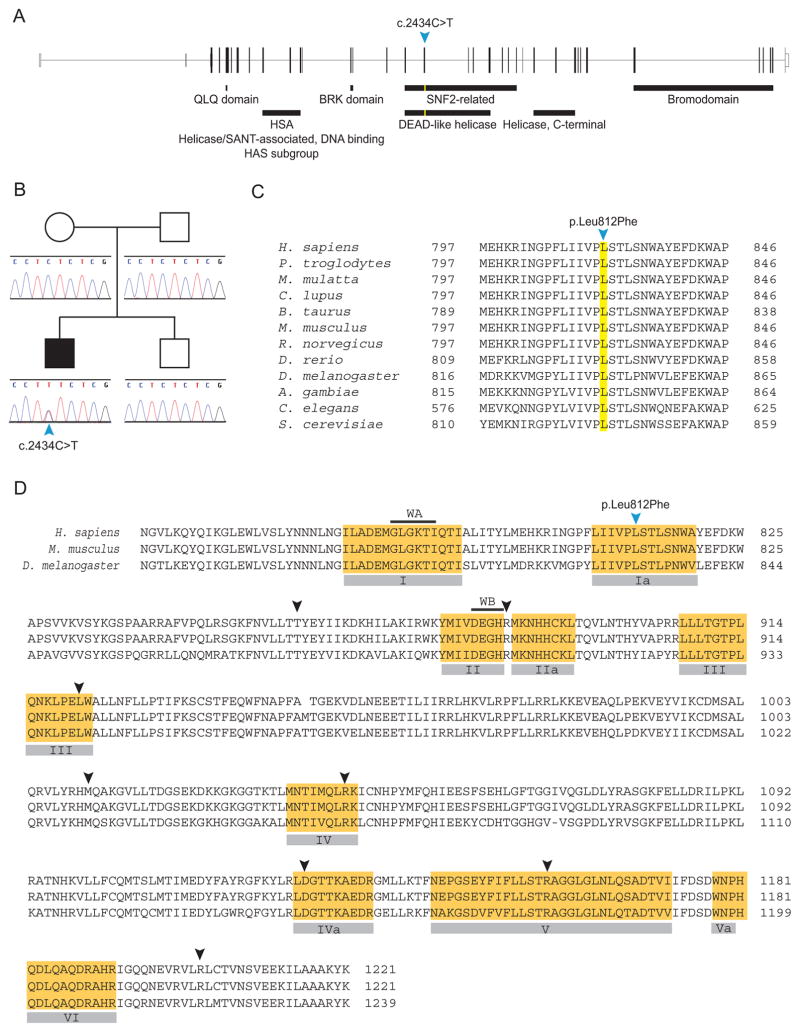

Upon report of the molecular cause of CSS [Tsurusaki et al. 2012], we chose to clarify the propositus’ diagnosis through molecular testing. Using the primers and methods described in the Supplementary Methods and Results, we sequenced all coding exons of the SWI/SNF complex genes (SMARCB1, SMARCA4, SMARCA2, SMARCE1, ARID1A, ARID1B) excepting exon 1 of ARID1A and ARID1B. This revealed several polymorphisms (Supplementary Table II) and a de novo SMARCA4 heterozygous missense mutation in exon 17 (NM_001128849.1:c.2434C>T; p.Leu812Phe)(Fig. 3). This mutation resides in motif Ia of the SNF2 conserved domain of SMARCA4 and is predicted to alter the active site (Fig. 3D) [Smith and Peterson 2005].

FIG. 3.

The propositus carries a novel de novo heterozygous missense mutation in SMARCA4. (A) Structure of the SMARCA4 gene and the motifs encoded by the exons. The propositus’ mutation c.2434C>T was located in exon 17, which encodes a portion of the SNF2 domain. (B) The propositus was heterozygous for c.2434C>T. This mutation was not detected in the blood DNA of any other family members. (C) The mutation p.Leu812Phe alters an amino acid conserved across species. (D) Amino acid sequence of the SMARCA4 SNF2 domain with the location of CSS-associated mutations represented by arrowheads. The conserved motifs characteristic of SNF2 domains are highlighted in orange and labeled below the sequence. The amino acids of the Walker A (WA, phosphate binding) and Walker B (WB, magnesium binding) sites are represented by black bars over the sequence. Compared to reported CSS-associated SMARCA4 mutations (black arrows), the propositus’ mutation (blue arrow) is the only one located in motif Ia.

DISCUSSION

We report a 7 year 9 month old patient with CSS and the first SMARCA4 mutation within the SNF2 Ia motif. With the exception of p.Lys546del, which removes a conserved amino acid between the HAS and BRK domains (Table I and Fig. 3), all reported SMARCA4 CSS-associated variants alter conserved amino acids within the SNF2 domain (Fig. 3D). Given that the SMARCA4 SNF2 domain forms the active site for ATP hydrolysis and couples ATP hydrolysis to chromatin-remodeling activity [Smith and Peterson 2005] and that the altered amino acids are conserved, we hypothesize that each mutation impedes SMARCA4 chromatin remodeling. A caveat to this explanation is the absence of deletion, nonsense or frameshift mutations of SMARCA4 among CSS patients; this observation could suggest that hemizygosity for SMARCA4 is lethal or causes a different disease, or that the genetic mechanism is not that of a hypomorph or amorph but rather that of a neomorph or antimorph. Arguing against these considerations, however, is the observation that loss of one dose of SWI/SNF complex members SMARCA2 or ARID1A is sufficient to cause CSS [Tsurusaki et al. 2012].

Since the SWI/SNF complex is a chromatin regulator of gene expression, there are several nonexclusive explanations for the pleiotropism of CSS and the presence of additional features in the propositus. These include differences in the consequences of the SMARCA4 mutations on enzymatic function, differences in the sensitivity of the genetic background to SWI/SNF dysfunction, and stochastic events.

Prior biochemical studies of the S. cerevisiae homologue Swi2/Snf2 have found that mutagenesis of the different conserved SNF2 domains have qualitatively and/or quantitatively different enzymatic consequences [Smith and Peterson 2005]. In S. cerevisiae substitution of an alanine for the proline immediately preceding the leucine mutated in motif Ia of the propositus reduced enzymatic activity, increased the Km for ATP, decreased the Vmax of ATP hydrolysis and decreased substrate turnover. This suggests that the p.Leu812Phe mutation observed in the propositus is a loss of function mutation. Secondly, because the S. cerevisiae mutation in domain Ia had different enzymatic consequences than mutations in the other domains, we speculate that the unusual phenotypic features of the propositus might be attributable to the distinctive enzymatic consequence of a mutation in SNF2 domain Ia of SMARCA4.

Alternatively, besides differences in genetic susceptibility, the pleiotropism of CSS might reflect a more general principle of SWI/SNF complex biology. Specifically, because individuals reported with SMARCA4 mutations inconsistently manifest cardiac malformations, behavioral and cognitive problems, skeletal anomalies and abdominal wall malformations, the manifestation of disease features might be arising from stochastic movement of gene expression past a disease threshold as demonstrated in model organisms for trait penetrance [Raj et al. 2010].

The propositus also demonstrates the evolution of the features of CSS. As an infant and young child, his face lacked the coarseness and thick lips typically associated with CSS. His facial features became more pronounced by 4 years and allowed a clinical diagnosis. Interestingly, the propositus and others reported with SMARCA4-associated CSS do not commonly have a thick upper lip as do individuals with other genetic causes of CSS [Kosho et al. 2013; Santen et al. 2013; Schrier et al. 2012; Tsurusaki et al. 2012; Van Houdt et al. 2012].

In summary, we associate a novel SMARCA4 mutation with CSS and expand the phenotypic spectrum of SMARCA4-associated CSS. We also find that the pathognomic clinical features of SMARCA4-associated CSS evolve and that the few reported individuals with this condition do not demonstrate a clear genotype-phenotype correlation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rosemarie Rupps for critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the Common Fund, Office of the Director, the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland) and grants from the Child & Family Research Institute (C.F.B.). C.F. Boerkoel is a scholar of the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and a Clinical Investigator at the Child & Family Research Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

References

- Bernstein BE, Birney E, Dunham I, Green ED, Gunter C, Snyder M. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489(7414):57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston RE, Bunker CA, Imbalzano AN. Repression and activation by multiprotein complexes that alter chromatin structure. Genes Dev. 1996;10(8):905–20. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.8.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosho T, Okamoto N, Ohashi H, Tsurusaki Y, Imai Y, Hibi-Ko Y, Kawame H, Homma T, Tanabe S, Kato M, Hiraki Y, Yamagata T, Yano S, Sakazume S, Ishii T, Nagai T, Ohta T, Niikawa N, Mizuno S, Kaname T, Naritomi K, Narumi Y, Wakui K, Fukushima Y, Miyatake S, Mizuguchi T, Saitsu H, Miyake N, Matsumoto N. Clinical correlations of mutations affecting six components of the SWI/SNF complex: detailed description of 21 patients and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161(6):1221–37. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner A, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, Wernig M, Hanna J, Sivachenko A, Zhang X, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Jaffe DB, Gnirke A, Jaenisch R, Lander ES. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature. 2008;454(7205):766–70. doi: 10.1038/nature07107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen TS, Ku M, Jaffe DB, Issac B, Lieberman E, Giannoukos G, Alvarez P, Brockman W, Kim TK, Koche RP, Lee W, Mendenhall E, O’Donovan A, Presser A, Russ C, Xie X, Meissner A, Wernig M, Jaenisch R, Nusbaum C, Lander ES, Bernstein BE. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. 2007;448(7153):553–60. doi: 10.1038/nature06008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Park EJ, Lee HS, Kim SJ, Hur SK, Imbalzano AN, Kwon J. Mammalian SWI/SNF complexes facilitate DNA double-strand break repair by promoting gamma-H2AX induction. Embo J. 2006;25(17):3986–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Rifkin SA, Andersen E, van Oudenaarden A. Variability in gene expression underlies incomplete penetrance. Nature. 2010;463(7283):913–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero OA, Sanchez-Cespedes M. The SWI/SNF genetic blockade: effects in cell differentiation, cancer and developmental diseases. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santen GW, Aten E, Vulto-van Silfhout AT, Pottinger C, van Bon BW, van Minderhout IJ, Snowdowne R, van der Lans CA, Boogaard M, Linssen MM, Vijfhuizen L, van der Wielen MJ, Vollebregt MJ, Breuning MH, Kriek M, van Haeringen A, den Dunnen JT, Hoischen A, Clayton-Smith J, de Vries BB, Hennekam RC, van Belzen MJ. Coffin-Siris syndrome and the BAF complex: genotype-phenotype study in 63 patients. Hum Mutat. 2013;34(11):1519–28. doi: 10.1002/humu.22394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santen GW, Kriek M, van Attikum H. SWI/SNF complex in disorder: SWItching from malignancies to intellectual disability. Epigenetics. 2012;7(11):1219–24. doi: 10.4161/epi.22299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrier SA, Bodurtha JN, Burton B, Chudley AE, Chiong MA, D’Avanzo MG, Lynch SA, Musio A, Nyazov DM, Sanchez-Lara PA, Shalev SA, Deardorff MA. The Coffin-Siris syndrome: a proposed diagnostic approach and assessment of 15 overlapping cases. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(8):1865–76. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrier Vergano S, Santen G, Wieczorek D, Wollnik B, Matsumoto N, Deardorff MA. Coffin-Siris Syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Fong CT, Stephens K, editors. GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CL, Peterson CL. A conserved Swi2/Snf2 ATPase motif couples ATP hydrolysis to chromatin remodeling. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(14):5880–92. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.5880-5892.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa SB, Abdul-Rahman OA, Bottani A, Cormier-Daire V, Fryer A, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Horn D, Josifova D, Kuechler A, Lees M, MacDermot K, Magee A, Morice-Picard F, Rosser E, Sarkar A, Shannon N, Stolte-Dijkstra I, Verloes A, Wakeling E, Wilson L, Hennekam RC. Nicolaides-Baraitser syndrome: Delineation of the phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A(8):1628–40. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsanam P, Winston F. The Swi/Snf family nucleosome-remodeling complexes and transcriptional control. Trends Genet. 2000;16(8):345–51. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsurusaki Y, Okamoto N, Ohashi H, Kosho T, Imai Y, Hibi-Ko Y, Kaname T, Naritomi K, Kawame H, Wakui K, Fukushima Y, Homma T, Kato M, Hiraki Y, Yamagata T, Yano S, Mizuno S, Sakazume S, Ishii T, Nagai T, Shiina M, Ogata K, Ohta T, Niikawa N, Miyatake S, Okada I, Mizuguchi T, Doi H, Saitsu H, Miyake N, Matsumoto N. Mutations affecting components of the SWI/SNF complex cause Coffin-Siris syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44(4):376–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houdt JK, Nowakowska BA, Sousa SB, van Schaik BD, Seuntjens E, Avonce N, Sifrim A, Abdul-Rahman OA, van den Boogaard MJ, Bottani A, Castori M, Cormier-Daire V, Deardorff MA, Filges I, Fryer A, Fryns JP, Gana S, Garavelli L, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Hall BD, Horn D, Huylebroeck D, Klapecki J, Krajewska-Walasek M, Kuechler A, Lines MA, Maas S, Macdermot KD, McKee S, Magee A, de Man SA, Moreau Y, Morice-Picard F, Obersztyn E, Pilch J, Rosser E, Shannon N, Stolte-Dijkstra I, Van Dijck P, Vilain C, Vogels A, Wakeling E, Wieczorek D, Wilson L, Zuffardi O, van Kampen AH, Devriendt K, Hennekam R, Vermeesch JR. Heterozygous missense mutations in SMARCA2 cause Nicolaides-Baraitser syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44(4):445–9. S1. doi: 10.1038/ng.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.