Abstract

BACKGROUND

A validated scale is needed for objective and reproducible comparisons of static forehead lines before and after treatment in practice and clinical studies.

OBJECTIVE

To describe the development and validation of the 5-point photonumeric Allergan Forehead Lines Scale.

METHODS

The Allergan Forehead Lines Scale was developed to include an assessment guide, verbal descriptors, morphed images, and real subject images for each scale grade. The clinical significance of a 1-point score difference was evaluated in a review of multiple image pairs representing varying differences in severity. Interrater and intrarater reliability was evaluated in a live-subject validation study (N = 295) completed during 2 sessions occurring 3 weeks apart.

RESULTS

A difference of ≥1 point on the scale was shown to reflect a clinically significant difference (mean [95% confidence interval] absolute score difference, 1.06 [0.91–1.21] for clinically different image pairs and 0.38 [0.26–0.51] for not clinically different pairs). Intrarater agreement between the 2 live-subject validation sessions was almost perfect (mean weighted kappa = 0.87). Interrater agreement was almost perfect during the second rating session (0.86, primary end point).

CONCLUSION

The Allergan Forehead Lines Scale is a validated and reliable scale for physician rating of static horizontal forehead lines.

Horizontal forehead lines are one of the first manifestations of facial wrinkles in the aging face1 and one of the areas patients are most likely to treat first, particularly women aged 30 to 34 years.2 Two different types of horizontal lines can occur on the forehead: dynamic lines and static lines.3 Dynamic forehead lines are visible during contractions of the muscles associated with facial expressions.3–6 Static forehead lines remain visible when muscles are relaxed and are caused by repeated muscle contractions in combination with age-related decreases in skin elasticity.3–6 Dynamic forehead lines are generally best treated with botulinum toxin, whereas static forehead lines may be treated with filler injections, alone or in combination with botulinum toxin.7–10

Because the treatment approaches differ for static and dynamic forehead lines, assessment scales for evaluating appearance before and after treatment should consider each type of line separately. This report describes the development and validation of a new photonumeric scale designed to rate static horizontal forehead lines (Allergan Forehead Lines Scale) that may be appropriate for treatment with filler injections (alone or in combination with botulinum toxin). The scale was created to meet FDA requirements for outcome assessments in clinical trials of new treatments.11 The objectives of this study were to determine the clinically significant difference in scale scores and to establish the interrater and intrarater reliability of the scale for rating severity of static horizontal lines of the forehead in live subjects.

Methods

Scale Development

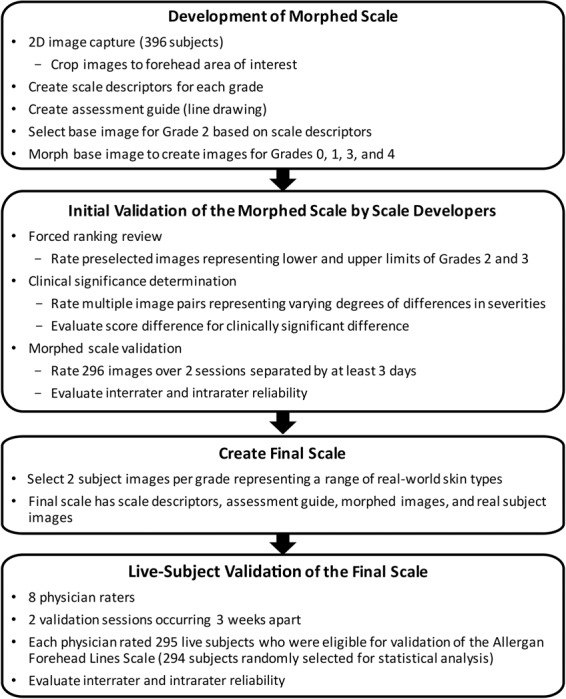

Figure 1 summarizes key steps in the creation and validation of the Allergan Forehead Lines Scale. A 9-member team comprising 5 external members (3 board-certified dermatologists, 1 board-certified oculoplastic surgeon, and 1 board-certified facial plastic surgeon) and 4 Allergan employees (2 dermatologists, 1 plastic surgeon, and 1 clinical scientist) developed the scale from a pool of subject images captured by Canfield Scientific, Inc. (Canfield, Fairfield, NJ). A total of 396 men and women aged 18 years or older with Fitzpatrick skin Types I through VI and in good general health volunteered for image capture. All subjects provided informed photograph consent before image collection. Subjects were excluded if they had anything that would interfere with visual assessment of the area of interest. Full facial 2-dimensional (2D) images were obtained using a 2D custom suite for facial imaging (Nikon D7100 Hi Res SLR). Images were cropped on the left and right sides at the temporal/lateral hairline and from the anterior hairline down to the upper eyelids to produce images of the forehead for the Allergan Forehead Lines Scale.

Figure 1.

Scale development and validation processes.

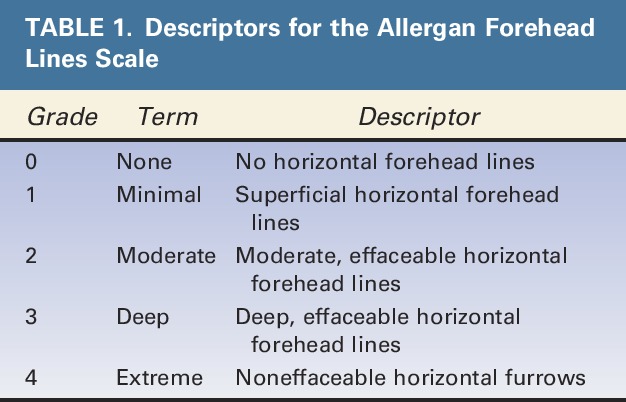

Scale descriptors were created for each of the 5 grades of the scale (Table 1). Two members of the Allergan team met with each member of the external scale development team for preliminary input on each scale grade. After preliminary scale grades were established, all 9 individuals involved in scale creation had a collaborative discussion about the scale grades and descriptors. The wording for each grade was then finalized by the Allergan team.

TABLE 1.

Descriptors for the Allergan Forehead Lines Scale

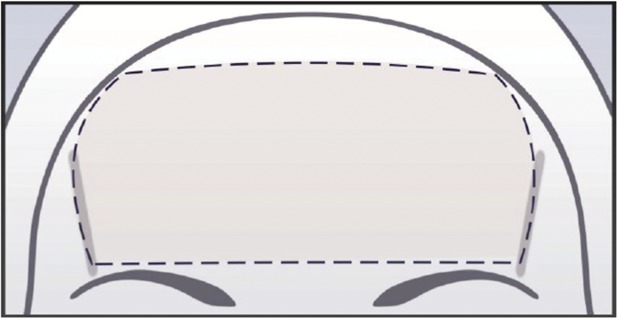

An assessment guide with a line drawing of anatomic markers demarcating the forehead area of interest was created by Canfield based on detailed instructions from the Allergan team regarding anatomic markers (Figure 2). The drawing was then revised by Canfield multiple times based on careful review by the Allergan team. The area of assessment was defined as the area between the left and right temporal fusion lines, from the eyebrows to the hairline.

Figure 2.

Assessment guide for the Allergan Forehead Lines Scale.

A base image to demonstrate Grade 2 was selected, and this image was morphed to represent all 5 grades of the scale. A Canfield graphics technician morphed the anatomic area of interest in the base image to match the descriptors provided for Grades 0, 1, 3, and 4. Alignment of the morphed images with the scale descriptors was achieved through an interactive process with the Allergan team.

A forced ranking review was performed to delineate the range of severity between Grades 2 and 3 and to confirm the selection of the best representative image to be used as Grade 2 on the scale. The 5 external scale developers performed the web-based forced ranking exercise on preselected images that represented the upper and lower boundaries of Grades 2 and 3.

To determine whether there was a clinically significant difference between grades of the scale, the 5 external scale developers were asked to perform an on-line clinical significance review. Multiple image pairs were selected to represent varying degrees of differences in severity (ranging from no difference to a 4-point difference). During the session, the scale developers determined whether there was a clinically significant difference (Yes/No) between images for each pair. After the session, the individual images from all image pairs were randomly mixed in with other images to be used in the morphed image scale validation (described in the following paragraph) and assigned a score by scale developers so that score differences between each image in each pair could be calculated.

The morphed image scale was validated by having the 5 external scale developers use the scale to rate randomized images representing all grades of the scale during 2 web-based sessions occurring at least 3 days apart. The scale developers rated a total of 296 images (120 images in Session 1 and 176 images in Session 2). The scale had acceptable interrater and intrarater agreement (>0.5), so scale development proceeded using the morphed images.

For both the clinical significance review and the morphed image scale validation, scale developers were provided uniform hardware by Canfield to complete the reviews. Before the reviews, the scale developers completed a web‐based PowerPoint training to familiarize themselves with the hardware, the review platform, and the purpose of the clinical significance and morphed image validation reviews. The scale developers were not allowed to discuss the reviews with one another, and each completed the image review independently.

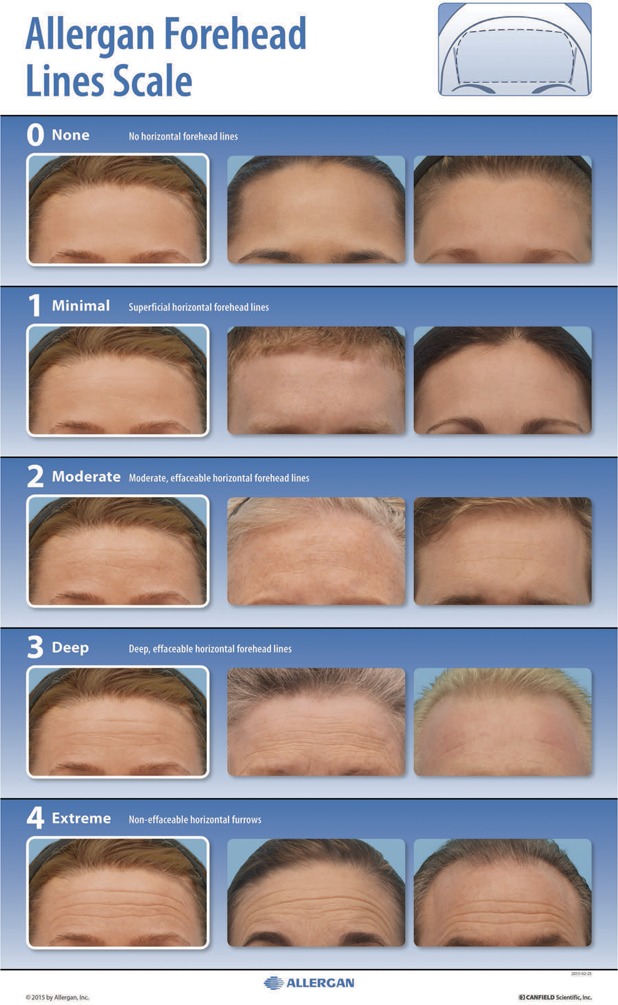

After the morphed image scale was created, 2 subject photographs representing each grade of the scale were selected to represent diversity in sex and Fitzpatrick skin type per grade. The final scale contained the scale descriptors for each grade, an assessment guide, the morphed images, and the real subject images (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Allergan Forehead Lines Scale assigns a grade from none (0) to extreme (4) that describes the depth and effaceability of static horizontal forehead lines defined by the diagram in the upper right corner.

Scale Validation

The interrater and intrarater reliability of the final scale was evaluated in a live-subject rating validation study. Eight physician raters experienced in using aesthetic photonumeric scales who were not involved in scale development participated in two 2-day live validation sessions occurring 3 weeks apart. Before the first live validation session, all physician raters were trained on the use of the scale in an interactive group training session using 4 example subjects. Raters were instructed to rate only static horizontal lines, to disregard vertical lines (e.g., glabellar lines), to select a grade based on the most severe line present (with 1 line being sufficient to determine grade), and to assess effaceable versus noneffaceable lines visually, not through attempts to manually efface lines.

All subjects who qualified for the initial image-capture events were invited to attend the live validation sessions. Subjects were instructed to arrive at the study center clean-shaven, to remove make-up and jewelry, to wear dark pants or jeans and a provided black T-shirt, to not drink alcohol excessively before the sessions, to try not to alter their usual routine (e.g., their facial care routine and normal sleep or hydration patterns) between sessions, and to not have tanning sessions or extensive sun exposure between sessions. On arrival at the study center for the first live validation session, subjects signed informed consent and were assessed for eligibility, age, sex, race (as reported by the subject), and Fitzpatrick skin type (determined by the investigator). Subjects were excluded if they had their photographs included in the scale, anything that would interfere with visual assessment of the forehead; any treatment with toxin/fillers, or surgery that would alter forehead appearance within 2 weeks of the first validation session or plans to have one of these procedures between the 2 sessions; or diagnosis of pregnancy. 2D images of each subject were collected at the first live validation session using a custom studio suite for facial imaging with Nikon D7100 Hi Res SLR. The first 5 subjects rated during the first validation session were considered run-in training subjects and were excluded from the analysis.

During the first and second live scale validation sessions, each physician rater evaluated all subjects on all scales (7 additional scales for other anatomic features were evaluated at the same sessions and are reported separately12–18). Raters had separate evaluation stations with an examination lamp, table, a stool for subject seating, supplies, and the photonumeric scale mounted and displayed for use in subject evaluation. Subjects presented themselves to each rater individually and proceeded from one rating station to the next in the same order until evaluated by all 8 raters. Raters were instructed to not discuss ratings with subjects or other raters. The raters took at least a 10-minute break every hour and at least a 30-minute lunch break to avoid rater fatigue.

Statistics

To determine the utility of the scale grades for detecting clinically significant differences in static horizontal forehead lines, absolute score differences for the image pairs deemed “clinically different” or “not clinically different” during scale development were summarized (mean, SD, range, 95% confidence interval [CI]). For the live-subject scale validation study, intrarater reliability was compared between Round 1 and Round 2 scores by calculating weighted kappa scores using Fleiss-Cohen weights.19 Kappa scores within the range of 0.0 to 0.20 indicate slight agreement, 0.21 to 0.40 indicate fair agreement, 0.41 to 0.60 indicate moderate agreement, 0.61 to 0.80 indicate substantial agreement, and 0.81 to 1.00 indicate almost-perfect agreement.20 Interrater agreement was measured by determining the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC [2,1]) and 95% CIs calculated using the formula described by Shrout and Fleiss.21 The a priori primary end point for the interrater agreement analysis was ICC (2,1) for the second rating session. SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses.

Sample Size Considerations

The sample size for the live-subject validation sessions was calculated using the method described by Bonett.22 With up to 10 raters and an ICC of 0.5, a total of 66 subjects were needed to have a 95% CI with a width of 0.2 for interrater reliability. Considering potential loss of subjects between the 2 rounds, at least 80 subjects were to be enrolled for the scale. Because 295 subjects were eligible for the scale validation analysis, the number of subjects evaluated using the scale was substantially larger than the preplanned sample size of 80, and the overall number of assessments for some grades of this scale was larger than that for the other grades. To minimize imbalance in the number of subjects across scale grades and to meet the sample size requirement, the mean score across the 8 raters for each subject was used to assign an overall grade for each subject and a subset of 83 subjects with minimal imbalance across the grades (∼16 subjects per each of the 5 grades) was randomly selected from the eligible subjects using a prespecified procedure. This random selection of the subset was performed 20 times. Interrater and intrarater agreements calculated for each of the 20 subsets were combined using SAS procedure PROC MIANALYZE to obtain the overall interrater and intrarater agreements.

Results

Clinical Significance Determination by Scale Developers

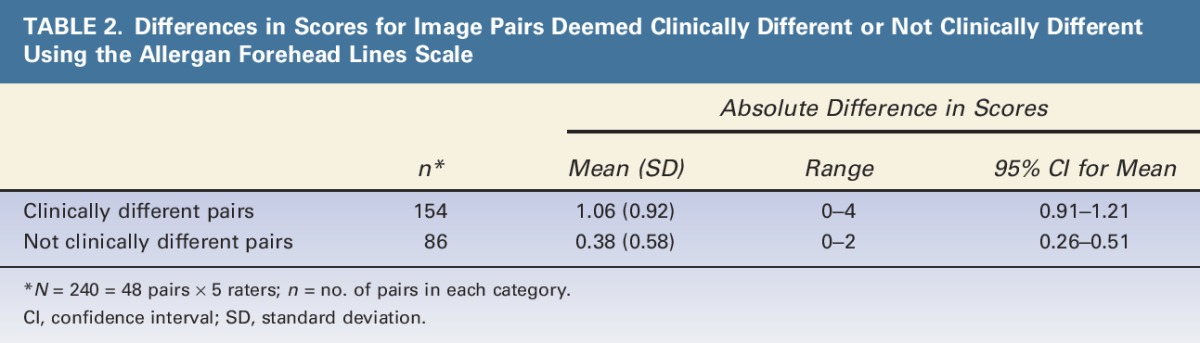

The mean (95% CI) absolute difference in scores was 1.06 (0.91–1.21) for image pairs deemed clinically different and 0.38 (0.26–0.51) for image pairs deemed not clinically different (Table 2). The 95% CIs for clinically different pairs did not overlap with the CIs for pairs deemed not clinically different, confirming that a 1-point difference in scores is clinically significant.

TABLE 2.

Differences in Scores for Image Pairs Deemed Clinically Different or Not Clinically Different Using the Allergan Forehead Lines Scale

Live-Subject Scale Validation

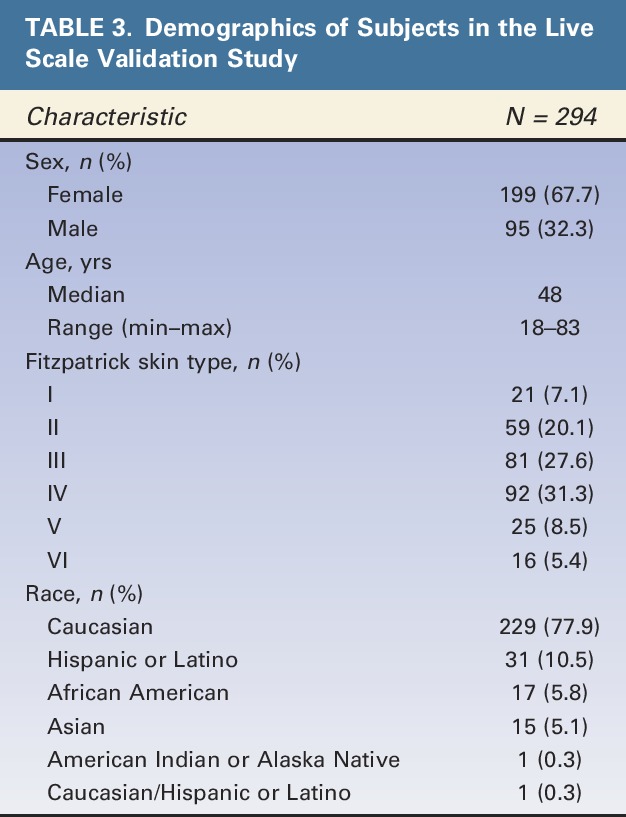

Of the 295 subjects eligible for the Allergan Forehead Lines Scale validation, 294 subjects were selected in at least one of the 20 random subsets for analysis of intrarater and interrater agreement. Demographic characteristics of subjects in the final scale validation set are shown in Table 3. Most subjects were female (68%), Caucasian (78%), and had Fitzpatrick skin Type III (28%) or IV (31%). Median age was 48 years, and a broad span of ages was represented (18–83 years).

TABLE 3.

Demographics of Subjects in the Live Scale Validation Study

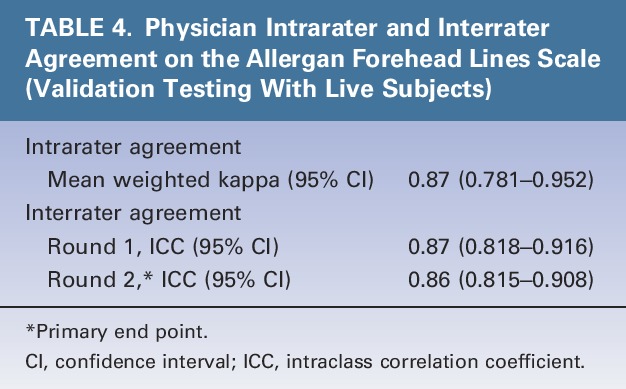

Intrarater agreement between the 2 live-subject rating sessions was almost perfect (mean weighted kappa = 0.87) (Table 4). Interrater agreement was almost perfect during the first (ICC = 0.87) and second rating sessions (ICC = 0.86, primary end point) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Physician Intrarater and Interrater Agreement on the Allergan Forehead Lines Scale (Validation Testing With Live Subjects)

Discussion

This study demonstrated almost-perfect interrater and intrarater agreement for the Allergan Forehead Lines Scale, indicating that this scale is reliable for multiple assessments of the same subject and across different raters. A 1-point difference in ratings on the scale was shown to reflect clinically significant differences, indicating that the scale has sufficient sensitivity for detecting clinically significant changes in the severity of static horizontal forehead lines.

One other validated scale for horizontal forehead lines has been published, which includes separate scales for static and dynamic forehead lines.3,23 The Allergan Forehead Lines Scale is intended only for the assessment of static lines that may be treated with filler injections. Static lines may be effaceable or noneffaceable (effaceable lines are not visible when the skin is manually stretched and tend to be shallower in depth, whereas noneffaceable lines remain visible when the skin is stretched and are typically deeper). The descriptors for each grade of the Allergan Forehead Lines Scale instruct the rater to visually determine whether the lines are effaceable (i.e., without manually stretching the skin). Most physicians with experience in the treatment of forehead rhytides are able to determine whether lines are effaceable by visual inspection alone.

Unlike the previously published forehead lines scale, which was validated using subject photographs, the Allergan Forehead Lines Scale was validated in live subjects. Scale validation in live subjects is important in establishing broad reliability for rating patients in the clinic and subjects in the setting of clinical trials. The Allergan Forehead Lines Scale uses morphed images to represent each grade to focus the rater's attention on the change from one grade to the next, with all other features remaining constant across scale grades. Real-world images representing a diverse range of skin types across sexes and races are an important component of the scale, as morphed images may not always translate to the broad array of appearances or physical changes observed in the clinic. Inclusion of both sexes and multiple ethnic groups in rating scales is important, as growing numbers of men and members of diverse ethnic groups are seeking aesthetic facial treatment.5,24

In the authors' experience, horizontal forehead lines may be worse in those people who habitually contract the frontalis muscle or have low eyebrow placement or descent. Males tend to have low eyebrow placement, making horizontal forehead lines a masculine attribute that may be considered unattractive in females. Mild horizontal forehead lines may be perceived as expressing interest, curiosity, and positivity. More severe static and dynamic lines indicate advanced age, however, and may be perceived as expressing disdain and surprise. In addition, they tend to be associated with bilateral brow ptosis, which may add perceived expressions of anger, concern, and sadness.5 In the author's experience, patients are usually satisfied with the rejuvenated appearance of a smoother brow; such satisfaction can lead to positive effects on self-esteem and overall outlook.

Study Limitations

The verbal descriptors for each grade on the scale are subjective. However, the descriptors were developed and refined during extensive collaboration between 9 clinical experts to minimize inherent subjectivity. The clinical significance of scale scores was determined solely by the scale developers. Although a 1-point change on the scale was considered clinically significant to the external scale developers, it may or may not be meaningful to patients. Changes less than 1 point may be meaningful for patients desiring a subtle change, whereas for some patients only dramatic changes may be meaningful. Hence, this scale is not intended for patient self-assessment of meaningful improvement. The FACE-Q is a validated patient satisfaction scale with subscales for appraisal of forehead lines and satisfaction with forehead that may be helpful for capturing a patient's perspective on forehead appearance before and after treatment.25,26

Conclusions

The Allergan Forehead Lines Scale demonstrated almost-perfect intrarater and interrater agreement among physicians, and 1-point score differences were shown to reflect clinically significant differences in horizontal lines of the forehead. This unique scale includes user-friendly diagrams, detailed verbal descriptions, and morphed and real subject images representative of both sexes and diverse skin types to provide standardized ratings that can be uniformly applied in day-to-day clinical practice and potentially in clinical trials, due to its validation in live subjects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following physicians for completing the scale validation study: David E. Bank, MD, FAAD; Sue Ellen Cox, MD; Timothy M. Greco, MD, FACS; Z. Paul Lorenc, MD, FACS; David J. Narins, MD, PC, FACS; William B. Nolan, MD; Robert A. Weiss, MD; and Margaret Weiss, MD. Statistical support was provided by Yijun Sun, PhD, and Shraddha Mehta, PhD of Allergan plc, Irvine, CA.

Footnotes

Supported by Allergan plc, Dublin, Ireland. Editorial support for this article was provided by Peloton Advantage, Parsippany, New Jersey, and was funded by Allergan plc. The authors received an honorarium for participating in scale development and validation.

B. Hardas, A. Marx, and D.K. Murphy are employees of Allergan plc. L. Creutz provided medical writing services at the request of the authors, which was funded by Allergan plc. The remaining authors have indicated no significant interest with commercial supporters.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors. The authors received no honorarium or other form of financial support related to the development of this article.

References

- 1.Luebberding S, Krueger N, Kerscher M. Quantification of age-related facial wrinkles in men and women using a three-dimensional fringe projection method and validated assessment scales. Dermatol Surg 2014;40:22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narurkar V, Shamban A, Sissins P, Stonehouse A, et al. Facial treatment preferences in aesthetically aware women. Dermatol Surg 2015;41(Suppl 1):S153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Hardas B, Kaur M, et al. A validated grading scale for forehead lines. Dermatol Surg 2008;34(Suppl 2):S155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujimura T. Investigation of the relationship between wrinkle formation and deformation of the skin using three-dimensional motion analysis. Skin Res Technol 2013;19:e318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carruthers JD, Glogau RG, Blitzer A. Advances in facial rejuvenation: botulinum toxin type a, hyaluronic acid dermal fillers, and combination therapies–consensus recommendations. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;121(Suppl 5):5S–30S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langsdon P, Petersen D. Management of the aging forehead and brow. Facial Plast Surg 2014;30:422–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monheit G. Neurotoxins: current concepts in cosmetic use on the face and neck–upper face (glabella, forehead, and crow's feet). Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;136:72S–5S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandt FS, Cazzaniga A. Hyaluronic acid gel fillers in the management of facial aging. Clin Interv Aging 2008;3:153–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubina M, Tung R, Bolotin D, Mahoney AM, et al. Treatment of forehead/glabellar rhytide complex with combination botulinum toxin a and hyaluronic acid versus botulinum toxin A injection alone: a split-face, rater-blinded, randomized control trial. J Cosmet Dermatol 2013;12:261–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Facial Esthetics. Wrinkles Treatment. 2015. Available from: http://www.facialesthetics.org/patient-info/facial-esthetics/wrinkle-treatment/. Accessed July 21, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. 2009. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones D, Donofrio L, Hardas B, Murphy DK, et al. Development and validation of a photonumeric scale for evaluation of volume deficit of the hand. Dermatol Surg 2016;42(Suppl 10):S195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carruthers J, Jones D, Hardas B, Murphy DK, et al. Development and validation of a photonumeric scale for evaluation of volume deficit of the temple. Dermatol Surg 2016;42(Suppl 10):S203–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sykes JM, Carruthers A, Hardas B, Murphy DK, et al. Development and validation of a photonumeric scale for assessment of chin retrusion. Dermatol Surg 2016;42(Suppl 10):S211–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donofrio L, Carruthers A, Hardas B, Murphy DK, et al. Development and validation of a photonumeric scale for evaluation of facial skin texture. Dermatol Surg 2016;42(Suppl 10):S219–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carruthers J, Donofrio L, Hardas B, Murphy DK, et al. Development and validation of a photonumeric scale for evaluation of facial fine lines. Dermatol Surg 2016;42(Suppl 10):S227–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones D, Carruthers A, Hardas B, Murphy DK, et al. Development and validation of a photonumeric scale for evaluation of transverse neck lines. Dermatol Surg 2016;42(Suppl 10):S235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donofrio L, Carruthers J, Hardas B, Murphy DK, et al. Development and validation of a photonumeric scale for evaluation of infraorbital hollows. Dermatol Surg 2016;42(Suppl 10):S251–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measure of reliability. Educ Psychol Meas 1973;33:613–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979;86:420–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonett DG. Sample size requirements for estimating intraclass correlations with desired precision. Stat Med 2002;21:1331–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flynn TC, Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Geister TL, et al. Validated assessment scales for the upper face. Dermatol Surg 2012;38:309–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. 2014 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report. 2015. Available from: http://www.plasticsurgery.org/Documents/news-resources/statistics/2014-statistics/plastic-surgery-statsitics-full-report.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwitzer JA, Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Baker SB, et al. Measuring satisfaction with appearance: validation of the FACE-Q scales for the nose, forehead, cheekbones, and chin. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;136:140–1.26397670 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Cano SJ. Development and psychometric evaluation of the FACE-Q satisfaction with appearance scale: a new patient-reported outcome instrument for facial aesthetics patients. Clin Plast Surg 2013;40:249–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]