Abstract

This retrospective study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of 3 surgical procedures for Spontaneous Supratentorial Intracerebral Hemorrhage (SICH).

A total of 63 patients with SICH were randomized into 3 groups. Group A (n = 21) underwent craniotomy surgery, group B (n = 22) underwent burr hole, urokinase infusion and catheter drainage, and group C (n = 20) underwent neuroendoscopic surgery. The hematoma evacuation rate of the operation was analyzed by 3D Slice software and the average surgery time, visualization during operation, decompressive effect, mortality, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) improvement, complications include rebleeding, pneumonia, intracranial infection were also compared among 3 groups.

All procedures were successfully completed and the hematoma evacuation rate was significant differences among 3 groups which were 79.8%, 43.1%, 89.3% respectively (P < .01), and group C was the highest group. Group B was smallest traumatic one and shared the shortest operation time, but for the lack of hemostasis, it also the highest rebleeding group (P = .03). Although there were different in complications, but there was no significant in pneumonia, intracranial infection, GCS improvement and mortality rate.

All these 3 methods had its own advantages and shortcomings, and every approach had its indications for SICH. Although for neuroendoscopic technical's minimal invasive, direct vision, effectively hematoma evacuation rate, and the relatively optimistic result, it might be a more promising approach for SICH.

Keywords: craniotomy, minimally invasive surgery, neuroendoscopic, spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage

1. Introduction

Spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage (SICH) is the second most common subtype and responsible for 9% to 27% of all strokes[1] worldwide, which affects more than 5 million people each year.[2] SICH is one of the deadliest disease, with a 30-day mortality of approximately 40%[3] and increasing to 54% at 1-year.[4] Long-term survivors are often saddled with permanent deficits, with up to 75% suffering significant disability[5] and only 12% to 39% of the survivors have favorable neurological functions recovered.[3,6] Although the incidence and mortality of hemorrhagic stroke decreased by 19%, 38% respectively in high-income countries, it increased by 6% in low- and middle-income countries and the burden of hemorrhagic stroke has increased between 1990 and 2010 by 47%.[7] In China, there was a noticeable increase of stroke incidence over the last 3 decades and the current stroke incidence (247/100,000) and mortality rates (115/100,000) in China appear to be the highest in the world. The proportion of SICH in China (25%) in 201 to 2013 was significantly greater than in high-income countries and similar to that observed in other low- to middle-income countries (14%–27%).[8]

Although such a poor outcome and no effective interventions available,[9] timely medical treatment was critical for SICH and optimal management was a priority. Even most patients could be managed conservatively; for patients with an extensive ICH, surgical evacuation of the hematoma was required available immediate.[10,11] Recent reports have shown that the surgical methods which mainly including craniotomy, burr hole, urokinase infusion, and catheter drainage, neuroendoscopic surgery for SICH are safe and effective.[12,13] However, which method is more better for SICH still lacking supporting evidence from controlled trials and remains difficult to select. In this study, we attempted to compare these 3 surgical methods for SICH and want to find a more promising treatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patient population

A total of 63 patients with SICH was studied retrospectively in our department between June 2015 and December 2016. All patients were diagnosed with SICH on initial computed tomography (CT) scans and the intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) volume was calculated by 3D Slicer Software (http://www.slicer.org). These patients were divided into 3 groups: craniotomy group (Group A, n = 21), burr hole, urokinase infusion, and catheter drainage group (Group B, n = 22), and neuroendoscopic surgery group (Group C, n = 20).

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for the patients in this study were as follows: diagnosed with acute SICH; CT scan showed hemorrhage from the subcortex, basal ganglia, internal capsule or thalamus, with or without intraventricular extension, and hematoma volume was 20 mL or above; Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores ≥ 5; stable vital signs. Exclusion criteria: the intracerebral hemorrhage was caused by secondary factors (eg, arteriovenous malformation; aneurysm; tumor stroke; head injury); GCS < 5; multiple intracranial hemorrhage; serious visceral disease or clotting disorders.

2.3. Surgical management

This study was approved by ethics committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and informed consents were obtained from all the subjects.

2.3.1. Craniotomy

In the craniotomy group, all patients underwent general anesthesia and hematoma evacuation was assisted by operative microscope. After open the dura, a small cortisectomy site was created and the hematoma cavity was entered. The hematoma was gradually evacuated by mild suction and active bleeding was controlled with standard neurosurgical techniques. After hematoma removal, the dura mater was closed by tension suture. Bone flap decompression was performed depending on the patients’ preoperative condition and the degree of intraoperative control of cerebral pressure. In some conditions, an extraventricular drainage was conducted before or after the operation.

2.3.2. Burr hole, urokinase infusion, and catheter drainage

Under general anaesthesia in the operating room, we placed a soft catheter into hematoma through a burr hole. The entry spot will be based on the result of image guidance to avoid functional domains and blood vessels. Clot aspiration was done with a 10 mL syringe until there was no longer any fluid component of the clot in the aspirate or until first resistance. And then the soft catheter connected to a 3-way stopcock and closed drainage system. Postoperative CT was done to confirm positioning of the soft catheter and stability of the residual hematoma. Hematoma was continuously liquefied by fibrinolysis agent (containing 20000U–40000U urokinase/2–3 mL saline solution) for 2 to 4 days. Routine CT follow-up was carried out 24 hours postoperatively and at 72 hours before catheter removal.

2.3.3. Neuroendoscopic surgery

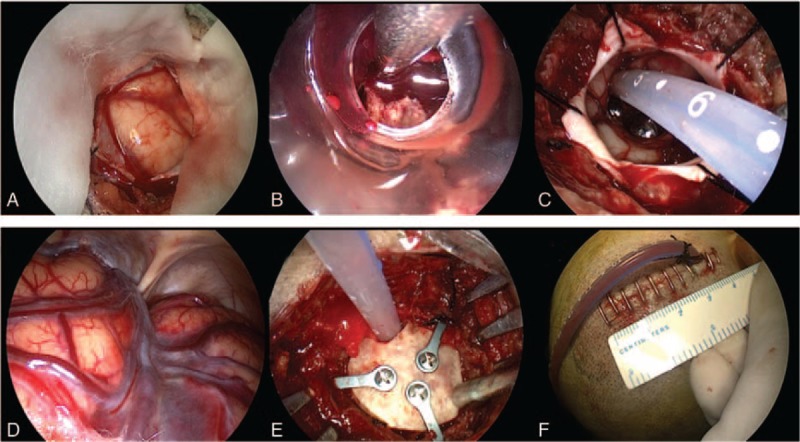

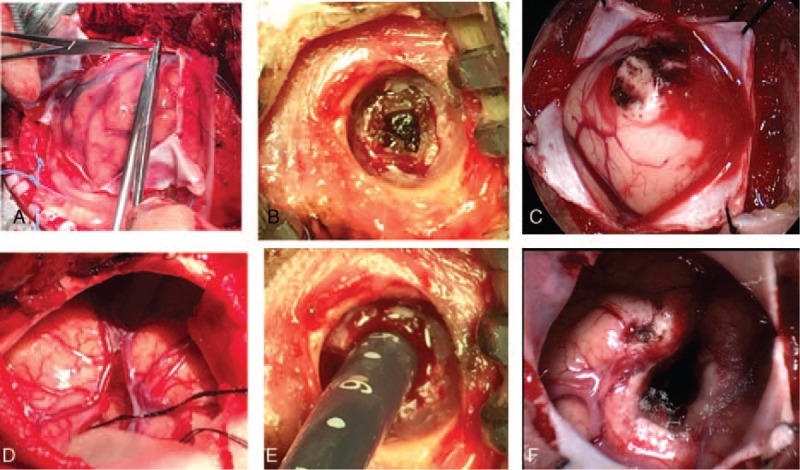

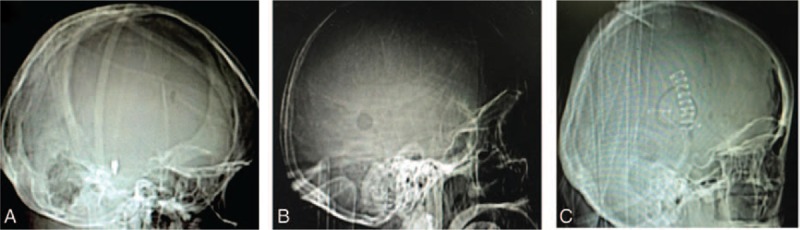

The surgical procedure was performed with patients under general anesthesia and in the supine position. For patients with nondominant-side, we used the corridor that traverses the shortest distance to the hematoma. Although for patients with deep hemorrhage on the dominant side, usually the transcortical corridor through the middle temporal gyrus was used. Usually, a linear scalp incision (4–5 cm) was made at the entry site. Then, a small circular craniotomy bone flap (approximately 2.5 cm in diameter) was made and the dura was tending. With the dura opened in cruciate fashion and a cortical incision was made (Fig. 1 A), a transparent sheath was inserted into the hematoma cavity (Fig. 1 B). A endoscope (Karl Storz, Germany) was introduced into the space and the hematoma will be evacuated under direct vision (Fig. 1 B). With adjusting the endoscope, most of the hematoma could be removed. But for the stiffly attached clot which usually the bleeding source, the suction power was controlled and this part of the clot was kept to avoid bleeding. For small bleeding vessels, a monopolar tip was used for coagulation the bleeding. To avoid brain tissue damage, the hematoma was removed under direct vision and hemostasis was completed by endoscopy. After removal of the hematoma, a soft catheter was inserted into the hematoma cavity to drain any residual liquid hematoma (Fig. 1 C) and the subdural space was checked (Fig. 1 D). After evacuation of the hematoma, the bone flap was reset and fixed, and then the scalp was closed (Fig. 1 D, E).

Figure 1.

Intraoperative images of neuroendoscopic surgery. A, After open the dura matter, the ICP was high. B, A transparent sheath was inserted into the hematoma cavity and hematoma was evacuated. C, A catheter was inserted into the hematoma cavity to drain any residual liquid hematoma after the hematoma removed. D, When operation finished, the ICP was drop and subdural space was checked. E, The small bone flap was recovered and fixed. F, The skin incision was short, only about 4 cm long.

2.4. Postoperative management

After hematoma evacuation, the patients were managed in the neurosurgical intensive care unit. Postoperative systolic blood pressure must be strictly controlled at <160 mmHg, and the presence of excessive fluid was not allowed. All patients underwent a follow-up CT scan within 3 days after surgery, 1 week after surgery, and at discharge. Hematoma volumes were calculated by 3D Slice software and the hematoma evacuation rate was calculated as follows: [(preoperative hematoma volume − postoperative hematoma volume)/preoperative hematoma volume] × 100%.

Outcomes include average surgery time, hematoma evacuation rate, visualization during operation, decompressive effects, mortality, GCS improvement, complications include rebleeding, pneumonia, and intracranial infection were analyzed.

2.5. Statistical analysis

SPSS 20.0 was used in this study, and measure mean data were expressed as mean ± SD. Significance level was set to 5%. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants were compared between groups upon admission using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). One-way ANOVA was also used to examine the GCS improvement, whereas categorical data were compared using χ2 tests.

3. Results

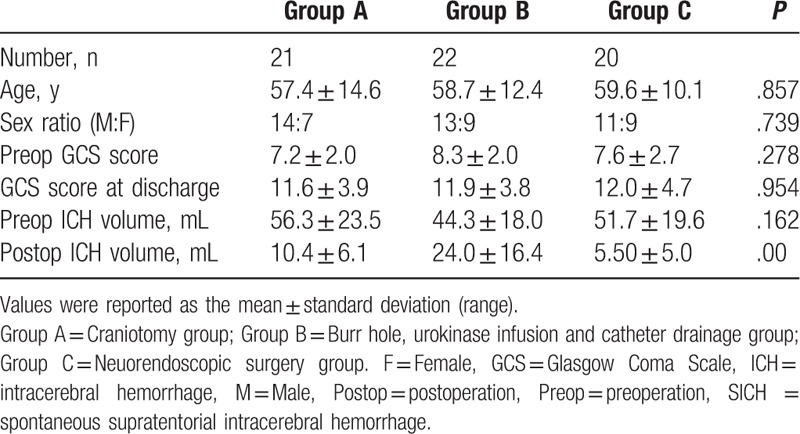

All cases among 3 groups could be matched each other and there was no significant differences among 3 groups in the baseline characteristics which including age, sex, the median preoperative GCS score, preoperative hematoma volume (Table 1).

Table 1.

General information of the 63 SICH patients.

In group A, the total number of patients was 21, 14 men and 7 women, ranging in age from 24 to 81 years (mean age, 57.4 ± 14.6 ys). The median preoperative GCS score was 7.2 ± 2.0 and preoperative hematoma volume was between 27 and 90 mL (mean, 56.3 ± 23.5 mL). In group B, the total number of patients was 22, including 13 men and 9 women, ranging in age from 35 to 86 years (mean age, 58.7 ± 12.4 ys). The median preoperative GCS score was 8.3 ± 2.0 and preoperative hematoma volume was between 21 and 84 mL (mean, 44.3 ± 18.0 mL). In group C, the median age of the 20 patients, 11 men and 9 women, who underwent endoscopic hematoma evacuation was 59.6 years. The median preoperative GCS score was 7.6 ± 2.7 and preoperative hematoma volume was between 30 and 122 mL (mean, 51.7 ± 19.6 mL) (Table 1).

All procedures were successfully completed and the average surgery time was compared among these 3 groups. In group A, the operation time ranged from 141.6 to 378.6 minutes, with mean length of 218.7 minutes. In group B, the operation time ranged from 27.6 to 50.6 minutes, with mean length of 36.9 minutes. In group C, the operation time ranged from 56.8 to 85.6 minutes, with mean length of 68.3 minutes. The average operation time was significant differences among these 3 groups (P < .01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Operative result of 63 patients with SICH.

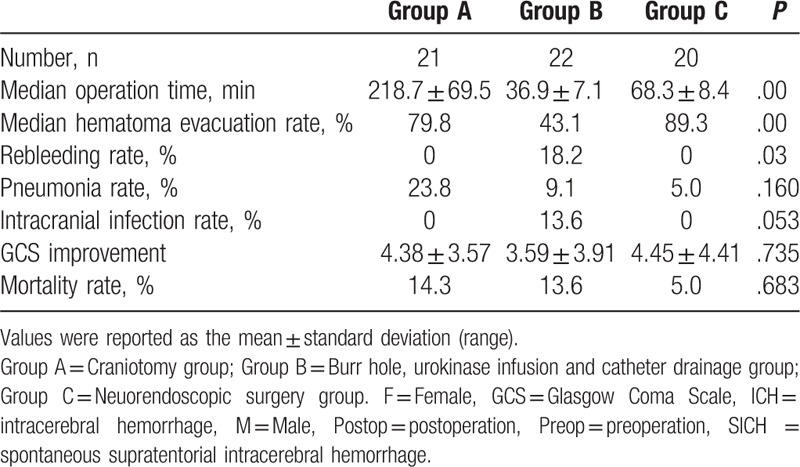

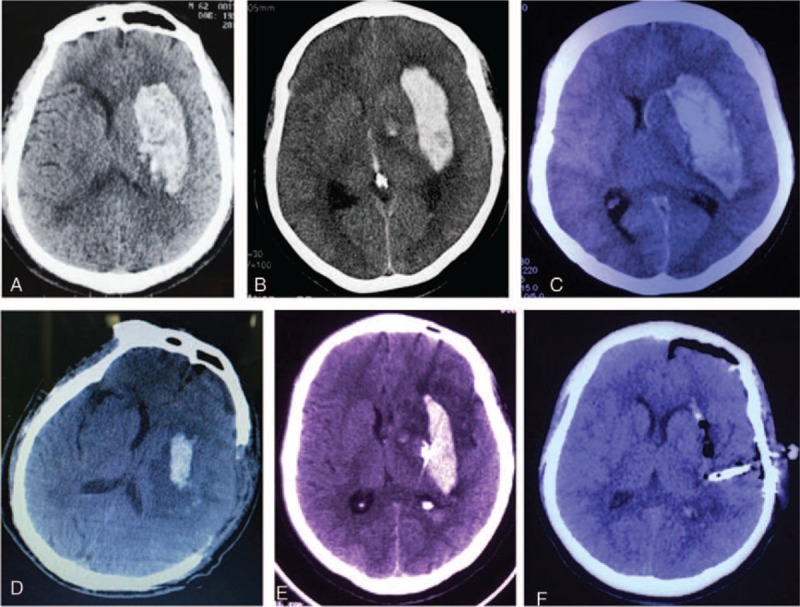

No significant difference in the preoperative hematoma volume was observed among these 3 groups (P = .162). The volume of the remaining hematoma measured by CT after the operation was 10.4 ± 6.1 mL in the group A, 24.0 ± 16.4 mL in group B, and 5.50 ± 5.0 mL in group C. The hematoma evacuation rate was significant differences among 3 groups which were 79.8%, 43.1%, 89.3% respectively (P < .01), and group C was the highest group (Figs. 2–8) (Table 2).

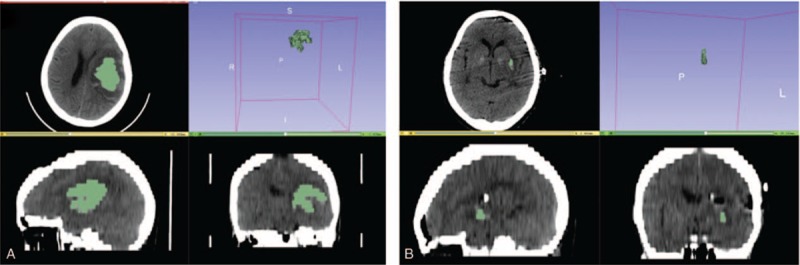

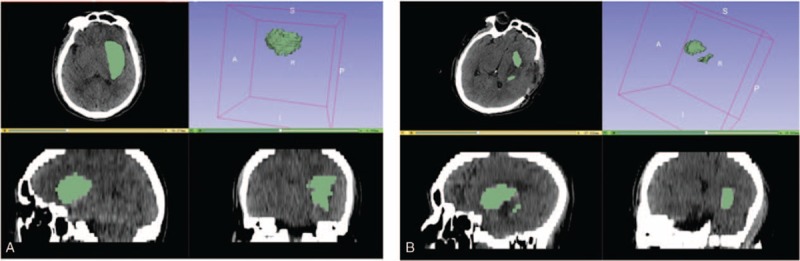

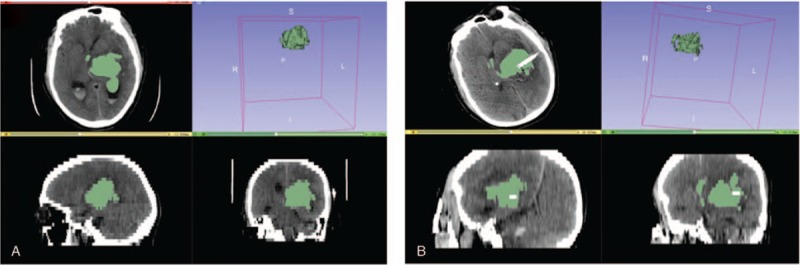

Figure 2.

Comparison the hematoma evacuation effect among 3 surgical approaches for left putaminal ICH. A and D, Preoperative and postoperative CT scan show that the hematoma was mostly removed by craniotomy approach. B and E, Preoperative and postoperative CT scan show that the hematoma was partially removed by burr hole, urokinase infusion and catheter drainage method. C and F, Preoperative and postoperative CT scan show that the hematoma was almost completely removed partially removed by neuroendoscopic surgery. CT = computed tomography.

Figure 8.

Calculation and analysis of hematoma volumes and hematoma evacuation rate by 3D Slice software in neuroendoscopic surgery patients. A, Preoperative hematoma volume was 30.9 mL. B, postoperative hematoma volume was 0.3 mL. The hematoma evacuation rate was 99.0%.

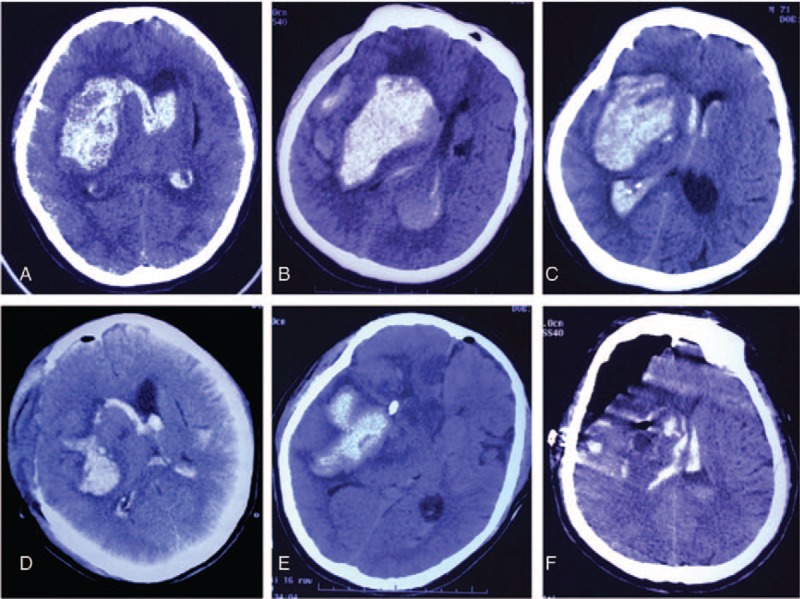

Figure 3.

Comparison the hematoma evacuation effect among 3 surgical approach surgical methods for right basal ganglionic hematoma. A and D, Preoperative and postoperative CT scan show that the hematoma was mostly removed by craniotomy approach. B and E, Preoperative and postoperative CT scan show that the hematoma was partially removed by burr hole, urokinase infusion and catheter drainage method. C and F, Preoperative and postoperative CT scan show that the hematoma was almost completely removed by neuroendoscopic surgery. CT = computed tomography.

Figure 4.

Comparison the hematoma evacuation effect among 3 surgical approach surgical methods for right parietal lobe hematoma. A and D, Preoperative and postoperative CT scan show that the hematoma was almost completely removed by craniotomy approach. B and E, Preoperative and postoperative CT scan show that the hematoma was partially removed by burr hole, urokinase infusion, and catheter drainage method. C and F, Preoperative and postoperative CT scan show that the hematoma was almost completely removed by neuroendoscopic surgery. CT = computed tomography.

Figure 5.

Comparison the hematoma evacuation effect among 3 surgical approach surgical methods for right frontal lobe hematoma. A and D, Preoperative and postoperative CT scan show that the hematoma was mostly removed by craniotomy approach. B and E, Preoperative and postoperative CT scan show that the hematoma was partially removed by burr hole, urokinase infusion, and catheter drainage method. C and F, Preoperative and postoperative CT scan show that the hematoma was almost completely removed by neuroendoscopic surgery. CT = computed tomography.

Figure 6.

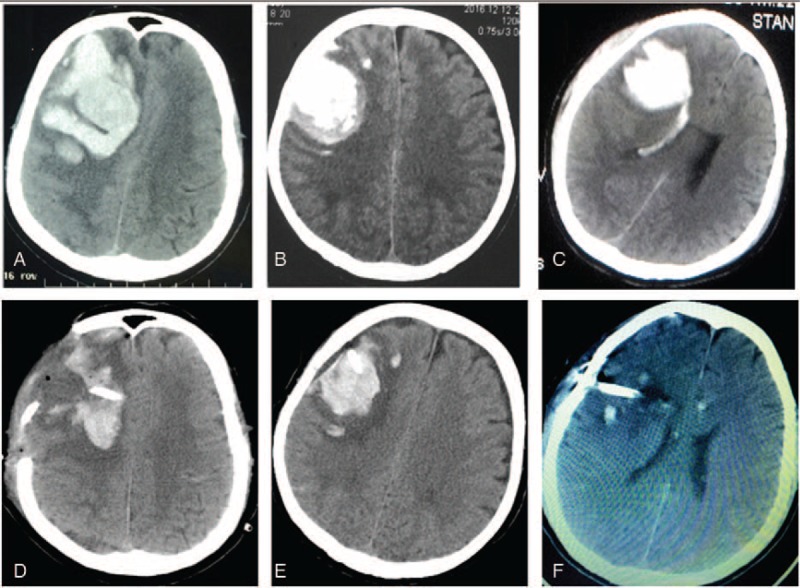

Calculation and analysis of hematoma volumes and hematoma evacuation rate by 3D Slice software in craniotomy patients. A, Preoperative hematoma volume was 56.2 mL. B, postoperative hematoma volume was 10.8 mL. The hematoma evacuation rate was 80.1%.

Figure 7.

Calculation and analysis of hematoma volumes and hematoma evacuation rate by 3D Slice software in burr hole, urokinase infusion and catheter drainage patients. A, Preoperative hematoma volume was 58.6 mL. B, postoperative hematoma volume was 45.1 mL. The hematoma evacuation rate was 23.0%.

In group A, the median preoperative GCS score was 7.2 ± 2.0 before surgery and it was going to 11.6 ± 3.9 at discharge. And in group B and C, there were 8.3 ± 2.0, 7.6 ± 2.7 before surgery, and 11.9 ± 3.8, 12.0 ± 4.7 at discharge respectively. The GCS score was significant improved after surgery in all 3 groups but there was no significant in GCS improvement (P = .735) (Table 2).

There were 3 patients died and the mortality rate was 14.3% in group A. Two patients died from severe pneumonia and one died because of multiple organ function failure. Whereas in group B, there were also 3 cases died and the mortality rate was 13.6%. One patient died from rebleeding in the brain and 2 died from brain infection. In group C, there was 1 patient died from the multiple systemic organ failure and mortality rate was 5.0%. And there was no significant differences among these 3 groups (P = .683) (Table 2).

The rebleeding rate was also different among these 3 groups (P = .03) (Table 2). In group A and group C, no case of rebleeding happened whereas 4 cases suffered from rebleeding in group B and rebleeding rate was 18.2% and 1 case died for this complication (Table 2).

Pneumonia was another severe complication, which might affect patient's prognosis. In group A, 5 patients suffered pneumonia and 2 of them died. Whereas in group B and C, there were only 2 cases and 1 case happened respectively and no case died from this complication. This might associated with a more aggressive and injury management in group A. There were 3 cases suffered intracranial infection and all these cases in group B, which might be caused by a placement of catheter in the brain longer than 7 days (Table 2).

4. Discussion

SICH caused high levels of morbidity and mortality and the pathophysiology was considered into ≤ 2 conceptual phases.[14] The first phase was immediate cellular injury caused by the acute bleed and early hemorrhagic expansion. The second phase was the persistent hematoma phase characterized by progressive damage to perihematomal tissue caused by mass effect, excitotoxic edema, progressive neurotoxicity, and so on. Animal models demonstrated that persistence of the hematoma results in progressive brain edema and metabolic distress which result in long-term disability. Surgical evacuation of SICH was a theoretically promising approach and early removal of hematoma would result in avoidance or mitigation of these secondary insults and substantially enhanced neurological recovery in humans.[14]

Although the benefit of surgical intervention for SICH was challenged by the surgical trial and the choice of the treatment always been a frequently discussed topic in neurology and neurosurgery.[15,16] There was no doubt that a large, life-threatening ICH should be evacuated,[17] and it was the second most common nontraumatic cerebral emergency surgery, which was currently performed in most neurosurgical departments.[18,19]

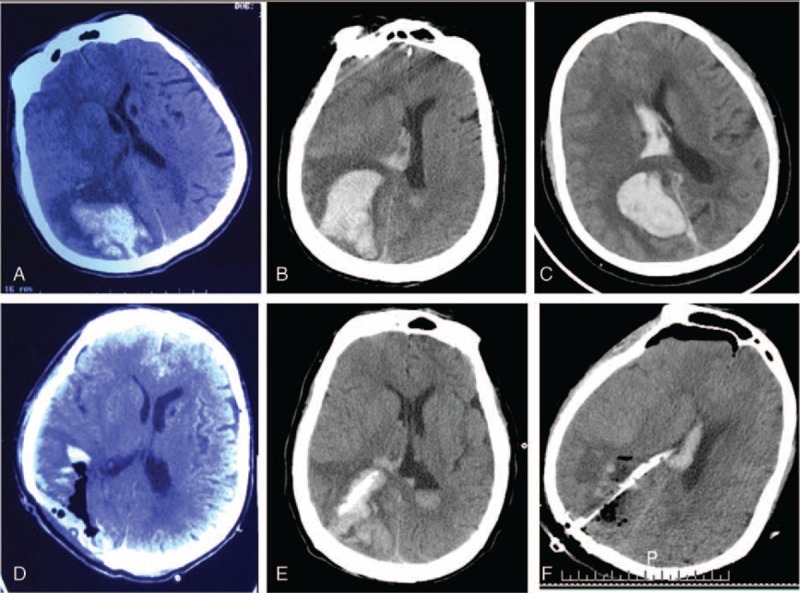

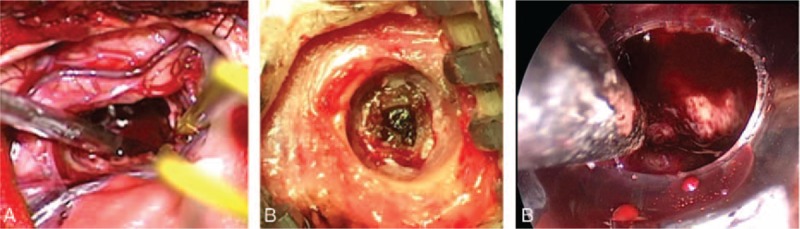

The intracranial pressure (ICP) was the main cause of death in patients with SICH which could increase suddenly and lead to brain herniation during the first 12 hours because of a mass effect associated with hematoma volume.[20] At the same time, increased ICP could cause a significant reduction in cerebral blood flow to the brain tissue surrounding the hematoma, potentially leading to ischemia. So, it was one of the most important parameters to evaluate in the surgical decision and reduce the mortality rate.[21] The early craniotomy surgery could immediate removal of the hematoma, dramatic reduction of ICP, relief of cerebral edema, improvement in local blood circulation, and a reduction in mortality.[22] A recent study showed that decompressive craniotomy (DC) might be useful to decrease the ICP and improve the prognosis in patients with large basal ganglia hemorrhage.[11] In 2015, edition of AHA/ASA guideline hold the opinion that DC with or without hematoma evacuation might reduce mortality for patients with SICH who were in a coma, had large hematomas with significant midline shift, or had elevated ICP refractory to medical management.[23] Moreover, in our study, we found craniotomy could evacuate hematoma effectively and remove the bone flap at the same time, whereas the drilling drainage and neuroendoscopic surgery could only removal hematoma, so the craniotomy was the most effectively treatment to decrease the ICP in patients with SICH (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Comparative analysis of decompression effect among 3 surgical approaches for SICH. The craniotomy (A and D) was better than or equal to the endoscopic surgery (E and F), whereas the decompression effect in drilling drainage (B and E) was not obvious. SICH = spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage.

Beside the extraordinary decompression effective, with the help of microscopy, craniotomy had also some other advantages such as good view and clearance of hematoma completely, easy hemostasia and so on, which could also help in outcomes (Fig. 10). However, conventional surgical hematoma evacuation through craniotomy was an invasive procedure and failed to protect the still functional brain tissue surrounding the hematoma and caused too much damage. A analysis of more than 45,000 patients from a study by Patil et al[24] demonstrated that the complication rate of this method was 41.2% and the mortality rate inhospital was 27.2%. The International Surgical Trial in Intracerebral Hemorrhage (STICH) concluded that there was no overall benefit to early surgery as compared with initial conservative treatment.[15] Furthermore, the STICH II trial found that early surgery did not significantly reduce the rates of death or disability at 6-month follow-up.[16] Even though, for patients who have lobar ICH > 30 mL and within 1 cm of the surface, removal of SICH by standard craniotomy might be considered.[15] Especially in patients with huge hemorrhage volume, or the state of illness progress rapidly, or in the early state of cerebral hernia, craniotomy should be the better choice.[23]

Figure 10.

Comparative analysis: the operation view of 3 surgical approaches for SICH. The endoscopic surgical operation field (C) was the best, better than microscope surgery (A), and there was almost no operation field (B) for burr hole, urokinase infusion and catheter drainage patients. SICH = spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage.

Another shortcoming of craniotomy was the longer time of operation. Although the influence of surgical procedures’ durations on mortality and morbidity has not been specifically studied, the results from a report on patients aged 80 years and older demonstrated that duration of surgical interventions might exacerbate detrimental effects of existing comorbidities.[25] Therefore, shortening of the surgical intervention's duration through minimally invasive approaches may also reduce perioperative morbidity.[26]

Minimally invasive surgery (MIS), including stereotactic aspiration and endoscopic surgery, had the advantage of minimal surgical injury and been widely used in the treatment of SICH (Figs. 11 and 12). It was obvious that the catheter drainage was the most minimally invasive and easiest surgery with the shortest duration among these 3 types of operation. In our study, the operation time of soft catheter drainage was 32.5 minutes which was much less than other 2 groups. Other advantages of this method includes: it could be performed bedside with local anesthesia in case of an emergency; the soft catheter avoided mechanical injury; and it was particularly suitable for sufficiently small ICHs and so on. However, this method had the limitation of cannot stop the bleeding directly and the rebleeding rate was much high than other groups. The average rebleeding rate for a simple aspiration was 5%,[27] whereas in our study it was 18.2%. The decompression effect of this method was also limited because clearance of hematomas was partially (Fig. 9). And this stereotactic aspiration was usually associated with longer waiting time before surgery, thus it was not suitable for unstable bleeding or herniation at an ultra-early stage of ICH.[28]

Figure 11.

Comparative analysis defects of bone in 3 surgical approaches for SICH. The craniotomy (A) was much large than endoscopic surgery (C) and drilling drainage (B). SICH = spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage.

Figure 12.

Comparative analysis skin incision in 3 groups. The craniotomy (A) was much longer than endoscopic surgery (C) and drilling drainage (B).

Even though, this method was adopted by more and more neurosurgeon. More recently, the MISTIE II (Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Rt-PA for ICH Evacuation Phase II) trial showed a strong trend toward clinical benefit in patients with ICH treated with MIS followed by catheter drainage with daily recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) irrigation.[29]

Volume of hematoma was another important parameter to evaluate the severity condition in SICH patients. Early evacuation of hematoma might protect brain tissue from the ischemia caused by the elevated ICP and reduce the noxious chemicals generated from hematoma. Therefore, effective removal of hematoma was the crucial principle of treatment with SICH for saving life and improving the long-term quality of life. In recent years, with good lighting and high-definition, amplified images endoscopes used in SICH, the treatment effect got a great progress (Fig. 10). The recent reports had demonstrated a high rate of SICH evacuation of 84% to 99%,[30] and in our study, we also got the same result which the average hematoma evacuate rate was 89.3% which was much high than other 2 groups (Figs. 2–8). The endoscopic technical also had other merits which including: short operative time in the skull; surgery can be performed and stop bleeding under direct vision, and had lower incidences of postoperative infection. However, its decompression was weaker than large bone flap craniotomy and it was more surgically invasive and took a longer time than the drilling method[28] (Fig. 9).

When all these data were analyzed, it became obvious that all these 3 methods had its own advantages and shortcomings, and every approach had its indications, so it was difficult to decide which method was the best approach for SICH. The major problem in all these studies might be the heterogeneity of the SICH patient groups with regard to their preoperative neurological status, different degrees of neurological impairment, consciousness levels, experience of the surgeon, and so on. Thus, it was an essential issue to select appropriate patients and homogenous group for determining whether patients truly benefit from different methods. But at the same time, for the relatively optimistic result, we believed that neuroendoscopical technical might be a more promising approach to SICH for its minimal invasive, direct vision and effectively hematoma evacuation rate.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: DC = decompressive craniotomy, GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale, ICP = intracranial pressure, MIS = minimally invasive surgery, SICH = spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage.

Drs. Huaping Zhang, Dong Zhao and Qianxue Chen are co-corresponding authors.

This work was supported by Nature Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China (2015CFB182), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81671306), Wuhan Science and Technology plan project (2016060101010067) and the foundation of China Scholarship Council. In this study, Q.C designed the clinical trial and performed the operation, collected and analyzed data, prepared figures, wrote, and reviewed the article. H.P.Z., D.Z., Z.H.Y., and K.Q.H. collected and analyzed the date and wrote the article. L.W., W.F.Z., and Z.B.C. collected and analyzed data, prepared figures and Q.X.C. designed the clinical trial, prepared figures, wrote and reviewed the article. H.Z., D.Z. and Q.C. are the co-corresponding author of this article. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, et al. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:355–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Krishnamurthi RV, Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, et al. Global and regional burden of first-ever ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet Glob Health 2013;1:e259–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, et al. Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Poon MT, Fonville AF, Al-Shahi Salman R. Long-term prognosis after intracerebral haemorrhage: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:660–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Anderson CS, Huang Y, Wang JG, et al. Intensive blood pressure reduction in acute cerebral haemorrhage trial (INTERACT): a randomised pilot trial. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:391–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mayer SA, Rincon F. Treatment of intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol 2005;4:662–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, et al. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2014;383:245–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wang W, Jiang B, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and mortality of stroke in China: results from a nationwide population-based survey of 480 687 adults. Circulation 2017;135:759–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Keep RF, Hua Y, Xi G. Intracerebral haemorrhage: mechanisms of injury and therapeutic targets. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:720–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kaya RA, Turkmenoglu O, Ziyal IM, et al. The effects on prognosis of surgical treatment of hypertensive putaminal hematomas through transsylvian transinsular approach. Surg Neurol 2003;59:176–83. discussion 183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li Q, Yang CH, Xu JG, et al. Surgical treatment for large spontaneous basal ganglia hemorrhage: retrospective analysis of 253 cases. Br J Neurosurg 2013;27:617–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kim SH, Kim JS, Kim HY, et al. Transsylvian-transinsular approach for deep-seated basal ganglia hemorrhage: an experience at a single institution. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg 2015;17:85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhou X, Chen J, Li Q, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke 2012;43:2923–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vespa PM, Martin N, Zuccarello M, et al. Surgical trials in intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2013;44(6 Suppl 1):S79–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mendelow AD, Gregson BA, Fernandes HM, et al. Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral haematomas in the International Surgical Trial in Intracerebral Haemorrhage (STICH): a randomised trial. Lancet 2005;365:387–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mendelow AD, Gregson BA, Rowan EN, et al. Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial lobar intracerebral haematomas (STICH II): a randomised trial. Lancet 2013;382:397–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Choo YS, Chung J, Joo JY, et al. Borderline basal ganglia hemorrhage volume: patient selection for good clinical outcome after stereotactic catheter drainage. J Neurosurg 2016;125:1242–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gaab MR. Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH): improvement of bad prognosis by minimally invasive neurosurgery. World Neurosurg 2011;75:206–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Angileri FF, Cardali S, Conti A, et al. Telemedicine-assisted treatment of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurosurg focus 2012;32:E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Arboix A, Comes E, Garcia-Eroles L, et al. Site of bleeding and early outcome in primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurol Scand 2002;105:282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zheng J, Li H, Zhao HX, et al. Surgery for patients with spontaneous deep supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage: a retrospective case-control study using propensity score matching. Medicine 2016;95:e3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang HZ, Li YP, Yan ZC, et al. Endoscopic evacuation of basal ganglia hemorrhage via keyhole approach using an adjustable cannula in comparison with craniotomy. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:898762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hemphill JC, 3rd, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2015;46:2032–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Patil CG, Alexander AL, Hayden Gephart MG, et al. A population-based study of inpatient outcomes after operative management of nontraumatic intracerebral hemorrhage in the United States. World Neurosurg 2012;78:640–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Turrentine FE, Wang H, Simpson VB, et al. Surgical risk factors, morbidity, and mortality in elderly patients. J Am Coll Surg 2006;203:865–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Beynon C, Schiebel P, Bosel J, et al. Minimally invasive endoscopic surgery for treatment of spontaneous intracerebral haematomas. Neurosurg Rev 2015;38:421–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gebel JM, Broderick JP. Intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurol Clin 2000;18:419–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wang WM, Jiang C, Bai HM. New insights in minimally invasive surgery for intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Neurol Neurosci 2015;37:155–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Spiotta AM, Fiorella D, Vargas J, et al. Initial multicenter technical experience with the Apollo device for minimally invasive intracerebral hematoma evacuation. Neurosurgery 2015;11suppl 2:243–51. discussion 251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang WH, Hung YC, Hsu SP, et al. Endoscopic hematoma evacuation in patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. J Chin Med Assoc 2015;78:101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]