Abstract

Niemann-Pick type C (NPC) disease is an inherited, progressive neurodegenerative disorder principally caused by mutations in the NPC1 gene. NPC disease is characterized by the accumulation of unesterified cholesterol in the late endosomes (LE) and lysosomes (Ly) (LE/Ly). Vorinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi), restores cholesterol homeostasis in fibroblasts derived from NPC patients; however, the exact mechanism by which Vorinostat restores cholesterol level is not known yet. In this study, we performed comparative proteomic profiling of the response of NPC1I1061T fibroblasts to Vorinostat. After stringent statistical criteria to filter identified proteins, we observed 202 proteins that are differentially expressed in Vorinostat-treated fibroblasts. These proteins are members of diverse cellular pathways including the endomembrane dependent protein folding-stability-degradation-trafficking axis, energy metabolism, and lipid metabolism. Our study shows that treatment of NPC1I1061T fibroblasts with Vorinostat not only enhances pathways promoting the folding, stabilization and trafficking of NPC1 (I1061T) mutant to the LE/Ly, but alters the expression of lysosomal proteins, specifically the lysosomal acid lipase (LIPA) involved in the LIPA->NPC2->NPC1 based flow of cholesterol from the LE/Ly lumen to the LE/Ly membrane. We posit that the Vorinostat may modulate numerous pathways that operate in an integrated fashion through epigenetic and post-translational modifications reflecting acetylation/deacetylation balance to help manage the defective NPC1 fold, the function of the LE/Ly system and/or additional cholesterol metabolism/distribution pathways, that could globally contribute to improved mitigation of NPC1 disease in the clinic based on as yet uncharacterized principles of cellular metabolism dictating cholesterol homeostasis.

Niemann-Pick type C (NPC)1 is a genetic disorder that exhibits an autosomal-recessive mode of inheritance (1). It is a progressive rare neurodegenerative disorder that affects one in every 150,000 children. NPC disease is characterized by the abnormal accumulation of cholesterol and other lipids in late endosomal (LE) and lysosomal (Ly) (LE/Ly) compartments (2, 3). NPC disease is caused by mutations in either NPC1 (95% of the cases) or NPC2 (5%) gene (1). Both NPC1 and NPC2 are predominately localized in the LE/Ly compartments, and play an important role in the recycling of LDL-derived cholesterol from the Ly to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and/or the plasma membrane (4). To date, over 300 disease-causing NPC1 mutants, including both missense and nonsense mutations, have been reported to be responsible for clinical disease (5). The most common mutation is a missense mutation of isoleucine to threonine at the 1061 position in NPC1 (denoted henceforth as NPC1I1061T). The NPC1I1061T mutant is a misfolded protein largely restricted to the ER where it is targeted for ER-associated degradation (ERAD) (6). As a consequence, and despite similar NPC1 mRNA levels found in wild-type (WT) and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts, NPC1 protein levels are decreased by 85% in NPC1I1061T fibroblast cells (6). Recent studies have shown the association of multiple chaperones such as heat shock proteins (Hsps) Hsp70/Hsp90 with the NPC1 protein, and have identified potential lysine residues that could contribute to ubiquitin-mediated degradation in the ER (7).

To date there is no cure for NPC disease, although several clinical trials are underway that focus on indirectly improving cholesterol homeostasis through bulk cholesterol management. These studies have shown that the treatment with the hydroxyl-propyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD), a chemical chaperone that can cage and extract cholesterol from membranes (8), reduces the accumulation of cholesterol and other lipids in both cellular and animal models (mice and feline) lacking NPC1 (null) or variant NPC1 protein that contain mutated (missense, nonsense, truncated) residues (9–12), substantially delaying disease onset by reducing intraneuronal storage and secondary markers of neurodegeneration. Moreover, HPβCD significantly increased the lifespan of both Npc1 (−/−) and Npc2 (−/−) mice (10). Recently, it has been shown that treatment of the NPC1 mutant cell lines with oxysterols, the oxidized derivatives of cholesterol, can act as pharmacological chaperones for enhancing the folding/trafficking pathways of the NPC1I1061T mutant, restoring cholesterol homeostasis in patient-derived fibroblasts (13, 14).

In addition to direct management of cholesterol homeostasis through bulk phase chemical chaperones such as HPβCD, histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors (HDACi's) have been shown to reduce the cholesterol accumulation in patient-derived fibroblasts (15). Several HDAC genes are transcriptionally upregulated in fibroblasts from patients with NPC disease (16). Application of the HDAC inhibitor Vorinostat reverses the impact of dysregulated HDAC genes on NPC1I1061Tfunction (16). Moreover, HDACi increases NPC1 protein level and reduce cholesterol accumulation in lysosomes (15, 16). Even though NPC1I1061T is misfolded, it retains functional activity (6), indicating that proper relocalization to the LE/Ly could contribute to mitigation of disease. Our recent study demonstrated that the treatment of HDACi's Vorinostat or Panabinostat while having no effect on npc1 null cells, leads to substantial correction of cholesterol homeostasis on expression ∼80% of clinically validated NPC1 mutants transiently expressed in npc1 null cells (17). Recently, a triple combination formulation (TCF) that included the HDACi Vorinostat, HPβCD, and polyethylene glycol (PEG) delayed the neuronal symptoms and extended the lifespan of the NPC1 (nmf164-D1005G) mouse model of NPC disease from 4 to 9 months of age (18). Combined, studies raise the possibility that HDAC inhibitors could potentially be used alone or in combination with HPβCD to manage NPC1 in the clinic.

Given the global impact of HDACi on the transcriptome and the cellular acetylome (19), it is of great interest to identify proteins whose expression level and/or stability in the cell is significantly altered by Vorinostat. Unbiased proteomics profiling could lead to a more comprehensive understanding of efficacy of Vorinostat in NPC1 disease from both basic and clinical perspectives. For comparative proteomics, we used amine-reactive tandem mass tag (TMT) to differentially label and quantify the proteome in NPC1I1061T cells treated in the absence or presence of Vorinostat. The labeled samples were analyzed by multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT) (20). We found 202 differentially expressed proteins that are involved in pathways related to protein folding, degradation and trafficking, energy metabolism, oxidation-reduction, and lipid metabolism. In addition, we found that Vorinostat modulated the expression of lysosomal proteins- most importantly lysosomal acid lipase (LIPA), a protein that contributes to the known LIPA->NPC2->NPC1 axis mediating cholesterol efflux in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (4). Our quantitative proteomics approach using Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061Tfibroblasts provides mechanistic insights of the impact of Vorinostat on NPC1 pathophysiology to further the development of HDACi as a potential drug for the treatment of NPC disease.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Histone deacetylase inhibitor Vorinostat/suberoylanilide hydroxamine (SAHA) was purchased from Cayman chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). DMSO, filipin, 4-Methylumbelliferyl Oleate (4-MUO), and lysosomal acid lipase (LIPA) inhibitor Orlistat were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Endo glycosidase H (endo H) was purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). The primary antibodies used in the experiments are described in the supplemental Table S1.

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

Human wild-type (GM05659), homozygous NPC1I1061T (GM18453) and LIPA (GM11851) fibroblasts were purchased from Coriell Cell Repositories (Coriell Institute for Medical Research). The cells were grown in DMEM medium supplemented with 2 mm l-Glutamine, 10% FBS, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin antibiotics. For expression studies, HeLa-shNPC1, HeLa-NPC1, and HeLa-NPC1I1061T stable cell lines were generated using a Lentiviral expression system. Briefly, Mission shRNA clone was purchased from Sigma against 3′UTR (TRCN000000542) of human NPC1 (pLKO-shNPC1) for knockdown of npc1 gene in human cell lines. The endogenous npc1 gene in HeLa cells was silenced with 3′-UTR shNPC1 Lentivirus (Sigma) to generate the npc1-deficient cells and stable clones were selected with 3 μg/ml puromycin antibiotics for 2 weeks. HeLa-shNPC1 cells stably expressing human NPC1 WT or the I1061T mutant were generated using Lentiviral construct (pLVX-Neo) and selection was performed with 600 μg/ml G418 antibiotics. Stable clones expressing the WT or I1061T NPC1 mutant protein were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 units/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 3 μg/ml puromycin, and 600 μg/ml G418.

Drug Treatment on NPC1 Fibroblasts

WT or NPC1I1061T patient fibroblasts were treated with DMSO (0.2%) (vehicle control) or Vorinostat (10 μm) for 72 h. Vorinostat (10 μm) was added to the WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts every 24 h to maintain the effect of drugs on NPC cells. Orlistat, a lysosomal acid lipase inhibitor was added to the cells as indicated in the figure legends.

Filipin Staining

Filipin staining was performed to visualize the intracellular cholesterol accumulation in NPC1 fibroblasts. Briefly, human WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts were grown on a 22-mm coverslip in a 6-well plate until they were 60–80% confluent. The cells were treated with DMSO (0.2%) or Vorinostat (10 μm) for 72 h. Medium was exchanged every 24 h in the presence Vorinostat (10 μm) to maintain the effect of the drug. The cells were washed twice with 1× PBS (phosphate-buffer saline), fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min and subsequently washed three times with PBS, followed by incubation with 1.5 mg/ml glycine for 10 min to quench the formaldehyde effect. The cells were then stained with 25 μg/ml filipin for 30 min at room temperature and rinsed three times with PBS. The coverslip was mounted on a glass slide using a Fluoromount G solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and visualized by fluorescence microscopy using a UV filter set at 340–380 nm excitation.

Sample Preparation and TMT Labeling

Protein extracts were obtained from NPC fibroblasts treated with Vorinostat or DMSO (vehicle control). Cell lysis was performed as described previously (21). TMT labeling was performed on three biological experiments according to the manufacturer's instructions with some modifications in the protocol. Briefly, 50 μg of a protein aliquot from each sample was acetone precipitated. The protein pellets were resolubilized in 100 mm TEAB supplemented with 0.1% SDS, reduced with TCEP for 1 h at 55 °C, and then alkylated with iodoacetamide for 30 min in the dark. The denatured proteins were digested with trypsin by overnight incubation at 37 °C. The tryptic digests were then labeled with TMT isobaric reagents from a TMT-duplex kit. For TMT labeling, TMT reagents were reconstituted in acetonitrile and TMT-126 label was added to 50 μg digests from three Vorinostat-treated samples whereas TMT-127 label was added to 50 μg digests from three DMSO-treated samples. The samples were incubated for 1 h at the room temperature. After incubation, 15 μl of 5% hydroxylamine solution was added to quench the labeling reaction. The TMT-labeled samples were combined to get three samples of Vorinostat- and the DMSO-treated pair. Acetonitrile was evaporated from the samples, diluted with buffer A (5% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid in water), and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 min to remove particulates. Vorinostat- and the DMSO-treated WT cells were labeled with TMT sixplex reagent; TMT labels 126, 127, and 128 were added to three biological replicates of DMSO-treated WT cells whereas labels 129, 130, and 131 were added to the three biological replicates of Vorinostat-treated WT cells. The samples were loaded into a biphasic trapping column for LC-MS/MS data acquisition by Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology (MudPIT) technology.

Mass Spectrometric Data Acquisition

MS analysis of the samples was performed using fully automated 12-step MudPIT method as previously described (22). Samples were loaded into a biphasic trapping column, which was successively packed with strong cation exchange particles (Partisphere SCX, 5 μm dia., 100 Å pores, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) and reverse phase particles (Aqua C18, 5 μm dia., 90 Å pores, Phenomenex) for about 2.5 cm length each. A 15-cm analytical column packed with reverse phase particles (Aqua C18, 3 μm dia., 90 Å pores, Phenomenex) was assembled with the trap column using a zero-dead-volume union (Upchurch Scientific, Oak Harbor, WA). LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on LTQ Orbitrap Velos (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) using a Top-10 data-dependent acquisition method. Full-scan MS spectra (m/z range 300–1600) were acquired in the Orbitrap with a resolution of 30,000 at m/z 400. Each full scan was followed by MS/MS scan of the most intense ions, up to 10, selected in the Orbitrap for higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD)-MS/MS with a resolution of 7500. The MS/MS spectra were collected using an isolation window of 2 Th and normalized collision energy of 45%. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD006005.

Data Analysis

Tandem mass spectra were extracted from the Xcalibur data system format (.raw) into MS2 format using RawXtract1.9.9.2. MS/MS spectra were searched with the ProLuCID algorithm (Version: October 2014) against human SwissProt database (downloaded in July 2013; number of protein entries = 20,210) that was concatenated to a decoy database in which sequence for each entry in the original database was reversed. The search parameters include 10 ppm precursor mass tolerance and 25 ppm for the fragment mass tolerance acquired in the Orbitrap. Trypsin was specified as cleavage enzyme with specificity selected to “semi-specific” and maximum number of internal missed cleavage selected to “unlimited.” The cut position were c-terminal of amino acids lysine and arginine. In addition, carbamidomethylation (57.02146) on cysteine and TMT modification (225.155833) on N terminus and lysine were defined as fixed modifications. No variable modifications were considered. ProLuCID outputs were assembled and filtered using the DTASelect2.0 (12) program to achieve a user-specified protein false discovery rate (1% for the current study). The proteins and peptides identified in the three experiements is given in supplemental Table S5.

Census (13), a software tool for quantitative proteomics analysis, was used for the extraction of TMT reporter ion intensities from the identified tandem mass spectra, correction of isotope contamination, and normalization. In Census, mass tolerance and intensity thresholds (sum of six reporter ion intensities in each spectrum) of the reporter ions were set at 0.05 Da and 10,000. Box plot of the log10-transformed normalized reporter ion intensities of the three TMT-duplex experiments is shown in supplemental Fig. S2A in the supporting information. Ratios of the normalized reporter ion intensities of peptides from 126- and 127-labeled samples (i.e. Vorinostat compared with DMSO treated cells) of each TMT-duplex experiment were computed. Protein ratios were derived as the median of the reporter ion intensity ratios of all MS/MS spectra (the ones that meet the threshold mentioned above) of all identified peptides associated with the protein. The protein ratios were then Z-score transformed: each protein's ratio was subtracted by the average ratio of all the quantified proteins in a TMT duplex experiment and the results were then divided by the standard deviation of the ratios. Z score of 1 indicates the protein is at least one standard deviation away from the mean protein expression ratio in the entire data set.

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

The relative expression of proteins in vorinostat-treated NPC1-I1061T cells were compared with DMSO-treated cells. The experimental design comprised three biological replicates of NPC1-I1061T cells that are treated with DMSO and three biological replicates that are treated with Vorinostat. One-sample t-tests were performed on the peptide spectra ratios to assign a p value to all the quantified proteins. All the p values were then corrected for multiple hypotheses testing by Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method. Differentially expressed proteins were selected based on BH-corrected p value, which should be < 0.05, and Z-scores, which should be ≤ −1 or ≥ 1 in each of the three TMT-duplex experiments. supplemental Table S3 in the supporting information includes the list of 202 differentially expressed proteins in Vorinostat-treated compared with DMSO-treated NPC fibroblasts. supplemental Table S6 provides the list of proteins quantified in WT cells treated with Vorinostat and DMSO.

For Western blotting statistical analysis between groups was performed using the GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA) with unpaired Student's t tests or one-way ANOVA. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D., unless otherwise stated. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks in the figures.

Proteins at the Borderline of Statistical Significance Threshold

Setting a threshold for selecting differentially expressed proteins can leave proteins on the other side of the threshold border that cannot be included in the differentially expressed list, but can be of functional significance regarding the system under study. For example, LIPA and NPC2 proteins are not in the differentially expressed list because the z-scores and p value selection criteria were not fulfilled in all the three replicates; however, the changes in their expression level was validated by Western blotting (Fig. 7A). Hence, we made an additional list that includes 45 proteins that qualified based on the z-score threshold (-1 ≤ z ≥ 1) in all three replicates but the BH-corrected p value threshold was found in only two of the three replicates, and 107 proteins that had a qualified BH-corrected p value threshold in all three replicates but the z-score threshold found for only two of the replicates. supplemental Table S4 in the supporting information lists these 152 proteins.

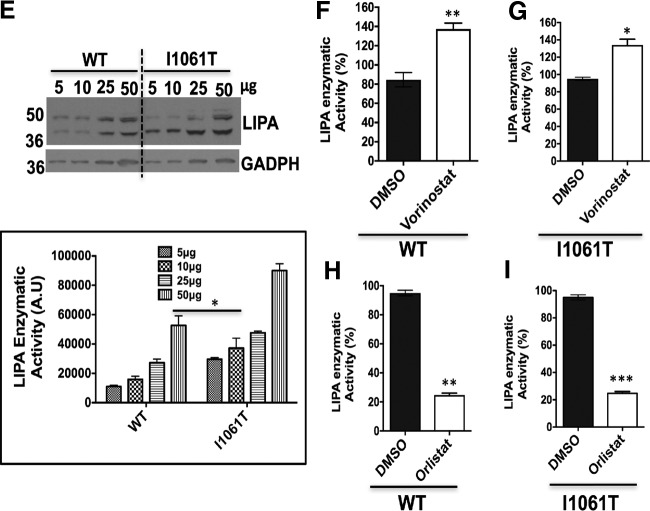

Fig. 7.

Vorinostat enhances the expression and activity of lysosomal acid lipase (LIPA) in WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. A, Human WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts were treated with DMSO and Vorinostat. Cell lysates were resolved using SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with LIPA specific antibody. GADPH was used as the loading control. Bar graph represents the relative amount of LIPA protein normalized to the loading control protein from three independent experiments. ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05. B, DMSO- or Vorinostat-treated WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts were treated with endo H as described in Methods. Endo H treated samples were resolved in 10% SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with LIPA specific antibody. Tubulin was used as loading control. Graph shows the quantification of endo H sensitive (white) or endo H resistant (black) form of LIPA proteins relative to total protein in each lane from two independent experiments. ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05. C, Effect of Vorinostat on LIPA trafficking in HeLa-shNPC1 (npc1−/−) cells stably expressing either WT or I1061T NPC1. Both WT and I1061T HeLa cells were treated with DMSO or Vorinostat (10 μm) for 72 h; cell lysates were incubated in the presence (+) or absence (-) of endo H. Samples were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and Western blotted using a LIPA specific antibody. D, Effect of Vorinostat on LIPA trafficking in HeLa-shNPC1 (npc1−/−) cells was analyzed using endo H digestion as described above followed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Graph represents the quantification of endo H sensitive (white) or endo H resistant (black) form of LIPA proteins relative to total protein in each lane. E, Various concentrations of cell lysates from WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts were immunoblotted to LIPA specific antibody (Top) and specific activity of LIPA (bottom) was performed as described in the Methods. F–G, Specific activity of LIPA found in DMSO- or Vorinostat-treated WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. WT and I1061T fibroblasts were treated with DMSO or Vorinostat (10 μm) for 72 h, followed by measurement of LIPA specific activity as described in the Methods. H–I, Specific activity of LIPA in the presence of DMSO or Orlistat (40 μm), an LIPA inhibitor for 72 h from WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. Cell lysates were obtained from drug-treated WT or NPC1I1061T fibroblasts and the specific activity of LIPA were measured as described in the Methods. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05. Graph shows the percent of LIPA enzymatic activity from three independent experiments.

Endoglycosidase H (endo H) Assay

Vehicle control or Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts were lysed with TNI lysis buffer as described previously (21). For endo H analysis of NPC1 protein, 300 μg of cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with rat anti-NPC1 antibody, followed by incubation with Protein A/G Sepharose beads to capture the antibody-antigen complex. NPC1 protein was eluted with 1× denaturation buffer (0.5% SDS, 40 mm DTT) and the samples were treated with the presence or absence of endo H overnight at 37 °C. The resultant samples were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. For the LIPA endo H assay, 20-μg of cell lysates was incubated with endo H overnight at 37 °C, followed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Lysosmal Acid Lipase (LIPA) Activity Assay

LIPA activity was performed according to the methods described previously (23, 24). The 4-methylumbelliferyl oleate (4MUO) stock solution was prepared in DMSO, then dissolved in 4% (w/v) Triton X-100 to 1 mm final concentration. Briefly, cells were washed with 1× PBS twice and lysed the cells with 1% Triton X-100 and passaged through a 23-gauge needle. Cell lysates were obtained by high-speed centrifugation at 14,000 rpm. Cell extract was diluted in a reaction buffer (200 mm sodium acetate pH 5.5, 0.02% Tween-20) and then added to the pre-mixed substrate of 50 μl of 1 mm 4MUO. Reactions were stopped with 1 m Tris pH 8.0 after 30 min and the fluorescence (355 nm excitation/450 nm emission) was monitored using a SpectraMax M2 fluorometer (Molecular Devices).

RESULTS

Vorinostat Restores the Function of NPC1 Protein in NPC1I1061T Fibroblasts

NPC1 is a glycoprotein with 13-transmembrane domains that is synthesized in the ER where it acquires 14 N-linked high-mannose glycans that are conserved between humans and mouse (1, 25). NPC1 is subsequently exported from the ER to the Golgi from where it is targeted to the late endosomal/lysosomal (LE/Ly) compartments to actively manage cholesterol homeostasis (26). Mutations in the NPC1 protein impair its ability to fold, traffic and/or properly manage cholesterol homeostasis in patient derived NPC fibroblasts leading to human disease (2, 27).

The NPC1I1061T mutation is the most prevalent mutation found in patients presenting with disease in the clinic in either the homozygous or, more often, the heterozygous state with another NPC1 variant. The heterozygous state with WT NPC1 lacks disease found in the carrier population (28). The expression level of NPC1 protein in NPC fibroblasts GM18453 in which both alleles carry the I1061T mutation in NPC1 gene (NPC1I1061T/I1061T, referred to hereafter as NPC1I1061T) is considerably lower compared with control fibroblasts (GM05659) that are derived from healthy individuals (Fig. 1A). The lower level of NPC1 in mutant fibroblasts reflects a folding defect that targets the misfolded and unstable NPC1I1061T mutant to ER-associated degradation (ERAD) (6).

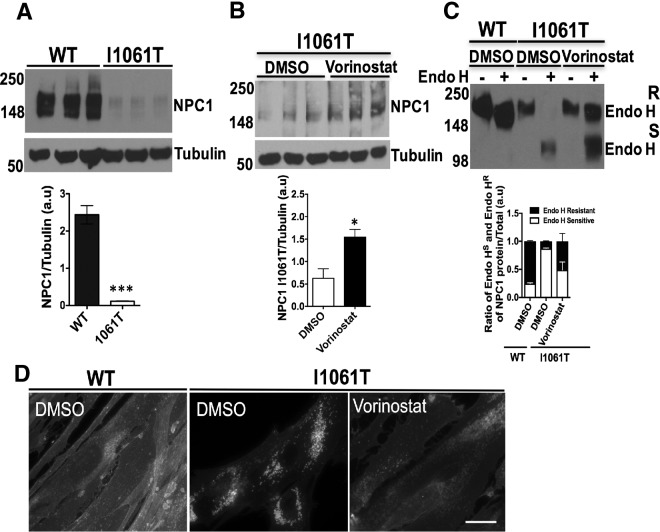

Fig. 1.

HDAC inhibitor Vorinostat restores NPC1 function in human NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. A, Expression level of NPC1 protein in human wild-type (GM05659) and I1061T mutant (GM18453) fibroblasts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with a rat anti-NPC1 antibody as described in Methods. B, I1061T mutant fibroblasts were treated with DMSO or HDAC inhibitor (HDACi) Vorinostat (10 μm) for 72 h. Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using a rat anti-NPC1 antibody. ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05. Bar graph shows the relative amount of NPC1 protein normalized to tubulin quantified from three independent experiments. C, Endoglycosidase H (endo H) sensitivity of NPC1 protein obtained from homogenates of WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts as described in Methods. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using a rat anti-NPC1 antibody. Bar graphs: endo H sensitive (white) or endo H resistant (black) glycoforms are quantified as percent of total NPC1 in each lane. D, Vorinostat reduces the cholesterol accumulation in LE/Ly compartments in NPC1I1061T cells. WT and I1061T fibroblasts were treated with DMSO or Vorinostat (10 μm) for 72 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with 25 μg/ml filipin for 30 min and examined using fluorescence microscopy as described in the Methods. Scale 10 μm.

Vorinostat is an FDA approved compound for cancer chemotherapy. It is currently one of the best-described HDAC inhibitors with a strong clinical history. It inhibits enzymatic activity of class I and II histone deacetylases by binding to its catalytic sites (29). Based on previous work that demonstrated the impact of Vorinostat on NPC1I1061T fibroblasts to restore cholesterol homeostasis (15), we treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts with DMSO (0.2%, vehicle control) or Vorinostat (10 μm) for 72 h. Using Western blotting with an NPC1 specific antibody, we observed a more than 2-fold increase the steady state level of human NPC1I1061T in fibroblasts as compared with vehicle control (Fig. 1B), a result consistent with the observation that Vorinostat has been shown to increase the expression of NPC1I1061T mutant in both human and murine embryonic fibroblasts (30). To further understand the effect of Vorinostat in correcting the folding, stability, trafficking and/or functional defect of NPC1I1061T in LE/Ly compartments, we employed endoglycosidase H (endo H). Incubation of immunoprecipitated cell lysates with endo H removes immature high-mannose N-linked glycans found in the ER resulting in an increase in migration using SDS-PAGE. Following ER export to the Golgi compartment, NPC1 glycoforms are processed to complex oligosaccharides that are endo H resistant in NPC1 wild-type protein. Treatment of NPC1I1061T fibroblasts with Vorinostat substantially restores the folding and trafficking defects of I1061T mutant to the LE/Ly compartments as shown by the acquisition of endo H resistance (Fig. 1C). This data suggests, that Vorinostat promotes the folding and stabilization for exit from the ER for delivery to the LE/Ly. In contrast, Vorinostat treatment has no significant effect on the NPC1 WT protein folding and trafficking, exhibiting similar endo H resistant to control vehicle (supplemental Fig. S1). Consistent with these observations, treatment of NPC1I1061T fibroblasts with 10 μm Vorinostat for 48 h resulted in a potent reduction in the punctate distribution of cellular cholesterol accumulated in the LE/Ly based on filipin staining (Fig. 1D, right panel) when compared with vehicle control treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 1D, middle panel), a diffuse distribution characteristic of that seen in WT NPC1 (Fig. 1D, left panel) as observed previously (15, 16).

Proteomic Profiling of Vorinostat Treated NPC1I1061T Fibroblasts Using TMT

Our recent isobaric labeling-based quantitative proteomic study identified differentially expressed proteins in WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts that might be causal or a consequence of pathogenesis in NPC disease (21). To now understand the impact of HDACi on restoring I1061T function in native patient fibroblasts, we used amine-reactive tandem mass tagging (TMT) to label and quantify the proteome of NPC1I1061T fibroblasts in the absence or presence of Vorinostat. Tandem mass tags (TMTs) are isobaric reagents with three structural components: a reporter ion, mass balancer, and a primary amine reactive group (20, 31). TMTs react with peptide N termini and the ε-amino group of lysine. After labeling, identical peptides in different samples appear as single peaks in MS scans. TMTs allow simultaneous identification and quantification of proteins during the tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) mode. In this method, the quantification relies on the reporter ions generated during MS/MS fragmentation of TMT-labeled precursor ions. The labeled samples were analyzed by multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT) (20). Isobaric labeling-based quantitative proteomics allows relative comparison of protein abundances across samples by measuring peak intensities of reporter ions released from labeled peptides. For comparative analysis of the NPC1I1061T proteome, three biological replicates of NPC1I1061T fibroblasts were treated with either vehicle control or 10 μm Vorinostat for 72 h. The samples were then processed, labeled with TMT reagents, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS as described in Methods. Fig. 2a shows a schematic representation of the experimental workflow used. A summary of the number of proteins, peptides, and spectra identified and quantified in the three TMT duplex experiments is given in supplemental Fig. S2 in the supporting information. The median of the ratios of the reporter ion intensities (126/127) from MS/MS spectra of peptides were used as protein ratios in the Vorinostat treated samples relative to vehicle control treated fibroblasts (supplemental Fig. S2C). In order to compare the three TMT experiments, the protein ratios were first transformed into Z-scores (see Methods). The boxplot in Fig. 2B shows the distribution of protein Z-scores in the three TMT-duplex experiments. A high correlation of Z scores was observed among all three replicates (Fig. 2C).

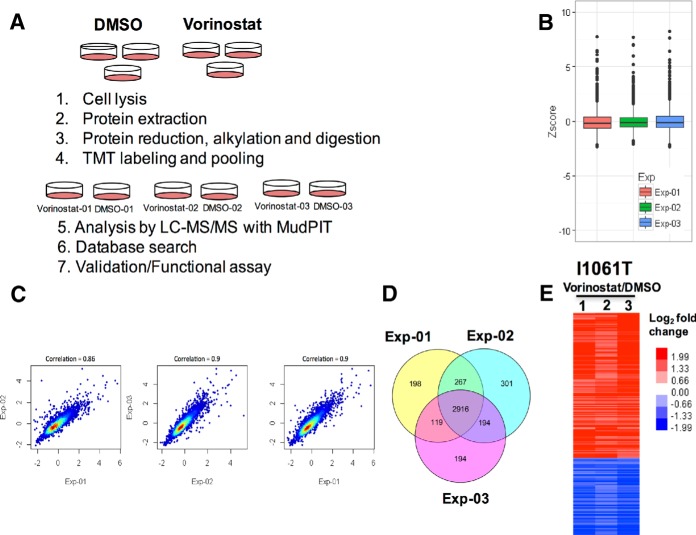

Fig. 2.

Tandem mass Tags (TMT) analysis of proteome of DMSO- and Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. A, Schematic representation of TMT-based quantitative proteomics of vehicle control (DMSO) and drug (Vorinostat) treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts cells. B, Distribution of protein z-scores in the three TMT-duplex experiments. Note: To fit the y axis scale, 4 data points were excluded from the plot. C, Scatterplot showing correlation of the z-scores among three TMT experiments of DMSO and Vorinostat treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. Note: To fit the x and y axes scale, 8 data points were excluded from the scatterplot. D, Venn diagram of overlap of proteins quantified across three TMT-duplex experiments. E, Heat map of differentially expressed proteins in Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts relative to vehicle control (DMSO) fibroblasts.

Differentially Expressed Proteins

Proteins identified and quantified in all three TMT experiments were used to generate a Venn diagram (Fig. 2D) that shows that 2916 of the total 4189 quantified proteins are detected in all three experiments. supplemental Table S2 lists the 2916 proteins identified in all three TMT experiments. We required the differentially expressed proteins to be identified with a Z-score −1 ≤ or ≥ 1, and BH (Benjamini Hochberg)-corrected p value ≤ 0.05 in each of the three TMT-duplex experiments. A total of 202 proteins fit the criteria among which 132 proteins were upregulated and 70 were downregulated (Fig. 2E). These proteins were identified with at least two MS/MS spectra. A list of the differentially expressed proteins is given in supplemental Table S3 in the supporting information. To understand whether changes in NPC1I1061T proteome is because of the mutation or nonspecific, we also performed TMT experiment on WT cells treated with either Vorniostat or vehicle control (supplemental Table S6)

Gene Ontology and Pathway Analyses

Total proteins quantified in all three replicates (i.e. 2916 proteins) were mapped for cellular ontology using the DAVID bioinformatics resources tool. 63% of the input proteins (supplemental Fig. S3, left panel) could be assigned to different cellular functions that showed minimum overlap in the ontology categories including cytosol, mitochondrial, ER, Golgi, and cytoskeleton (supplemental Fig. S3, right panel). Next, we used the differentially expressed proteins (202 proteins), as an input for gene ontology analysis, which revealed that one-third of the proteins were mitochondrial associated. Although other cellular components were not significantly enriched in a particular category, we observed proteins that have functions consistent with contribution to the activity of ER, Golgi, and LE/Ly compartments.

We further analyzed the biological functions of the differentially expressed proteins by mapping against the KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathways (accessed through DAVID analysis tool). Most of the proteins in the data set mapped to metabolic pathways, indicating that Vorinostat treatment increased the expression of many metabolic enzymes. supplemental Fig. S4 shows significantly enriched metabolic pathways including TCA cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, and branched-chain amino acid (valine, leucine, and isoleucine) degradation pathways. In addition, the differentially expressed data set contains proteins that regulate the folding and degradation of proteins, membrane trafficking, ROS, metabolism and transport of lipids (supplemental Table S3).

Validation of the Protein Response to Vorinostat in NPC1I1061T Fibroblasts

Protein Folding and Degradation

A subset of differentially expressed proteins in our TMT data set suggests the potential involvement of protein folding and degradation pathways in the Vorinostat response. We validated seven proteins including FKBP10, SERPINH1, BAG2, GALNT5, TRAP1, USP15, and ERP44 by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A–3G). FK506 binding protein 10 (FKBP10) belongs to peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase family, resides in ER, and functions as molecular chaperone. Studies have shown that the depletion of FKBP10 promotes folding and trafficking of β-glucocerebrosidase (GBA) protein in Gaucher's disease (32). The expression level of FKBP10 is significantly reduced in Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 3A). SERPINH1/Hsp47 belongs to the serpin superfamily of serine proteinase inhibitors and is an ER localized chaperone that, for example, is involved in collagen biosynthesis and folding pathways (33). Vorinostat reduces the expression level of SERPINH1 in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 3B). Although validated as being significantly differentially expressed by TMT, BAG2 is a critical regulator of cytosolic Hsc/Hsp70 chaperone activity (34). BAG2 showed a modest but not statistically significant change based on Western blotting (Fig. 3C). ERP44 is a multifunctional ER-associated chaperone and involved in protein folding, calcium signaling, and normal redox homeostasis (35). Upon treatment with Vorinostat the expression level of ERP44 is significantly increased in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 3D). USP15 belongs to ubiquitin-specific protease (USP) family of deubiquitinating enzymes. USP15 mediates polyubiquitin chain disassembly through hydrolysis of ubiquitin-substrate bonds in the target proteins (36). The upregulation of USP15 in response to Vorinostat treatment in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts suggests a potential role of USP15 in stabilizing NPC1I1061T protein for exit from the ER in patient fibroblasts (Fig. 3E). In the Golgi, GalNT5 enzyme transfers N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) from UDP-GalNAc to the hydroxyl group of serine or threonine in target proteins (37). With Vorinostat treatment, the expression level of GALNT5 was reduced in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 3F), potentially indicating a role for this activity in NPC1 function or stability in downstream LE/Ly. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated protein 1 (TRAP1) is a mitochondrial associated Hsp90 chaperone and interacts with tumor necrosis factor type 1. TRAP1 may be involved in regulating cellular folding related stress responses in the mitochondria (38) as Vorinostat treatment leads to an upregulation of the level of TRAP1, an activity that could perhaps help cope the elevated stress conditions in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts in response to cholesterol dys-homeostasis (Fig. 3G). Taken together, our study suggests that the treatment of Vorinostat modulates many stress related proteins involved in managing protein misfolding in response to the maladaptive environment of the NPC1I1061T related loss of cholesterol homeostasis.

Fig. 3.

Impact of Vorinosat on the expression level of proteins involved in protein folding pathways in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. A–G, Western blot analysis of cell lysates from DMSO or Vorinostat treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. Cell lysates were resolved in SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the indicated antibodies as described in Methods. In Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts FKBP10 (A), SERPINH1 (B), BAG2 (C), and GALNT5 (F) were downregulated whereas ERP44 (D), USP15 (E), and TRAP1 (G) were upregulated. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, and n.s., not significant (p > 0.05). Bar graph represents the relative amount of the indicated protein normalized to the loading control GADPH or tubulin from three independent experiments.

Oxidation Stress and Energy Metabolism

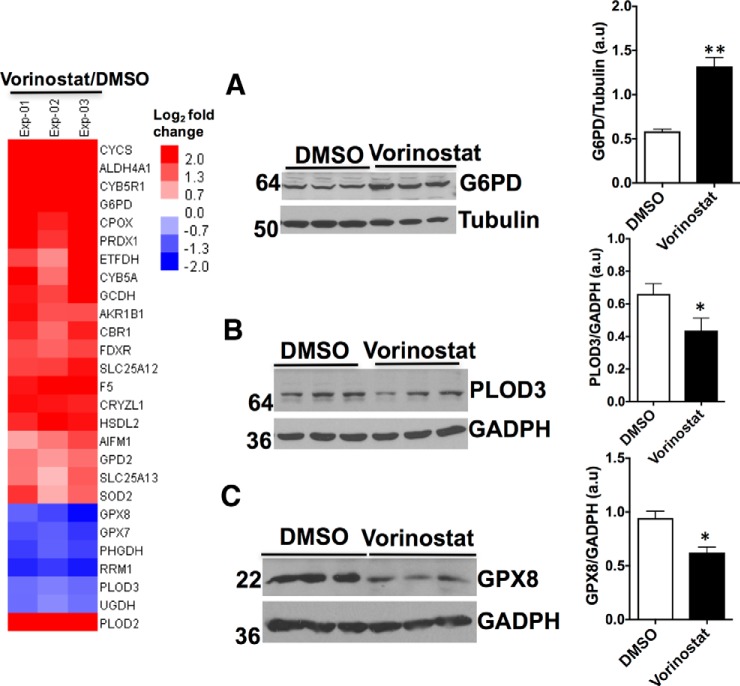

NPC disease is associated with increased level of cholesterol in the mitochondria that impairs their normal biological functions (39). Energy metabolism is significantly altered in both NPC disease patient-derived fibroblasts and murine models leading to sensitivity to oxidative stress (40). Consistent with these observations, we have recently shown using TMT that proteins involved in energy metabolism are markedly altered in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts compared with WT fibroblasts (21). Quantitative analysis of Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts showed a strong reversal of this trend (Fig. 4 and 5). For example, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) catalyzes the rate-limiting step of glucose-6-phosphate into the pentose-phosphate pathway (41). Whereas its level is reduced by the I1061T mutation (21), its level is increased in Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 4A. Other examples include PLOD3 that catalyzes oxido-reductase activity in the hydroxylation of lysine residues in collagen-like peptides. It is significantly reduced in Vorinostat-treated NPC1 fibroblasts, reversing the trend seen in NPC1I1061T cells compared with wild-type cells (21) (Fig. 4B). Moreover, the expression level of GPX8, a member of the glutathione peroxidase redox family, that is elevated in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts was markedly reduced with Vorinostat treatment (Fig. 4C), perhaps limiting oxidative stress imposed by improper distribution of cholesterol.

Fig. 4.

Effect of Vorinostat on the expression level of proteins involved in oxidation-reduction reactions in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. Heat map of differentially expressed proteins involved in oxidation-reduction reactions in DMSO or Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts quantified by TMT. A–C, Western blot analysis of cell lysates from DMSO or Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. Cell lysates were resolved using SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with the indicated antibodies as described in Methods. G6PD (A) was upregulated, whereas PLOD3 (B), and GPX8 (C) were downregulated. ** p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Bar graph represents the relative amount of protein normalized to the loading control GADPH, or tubulin from three independent experiments.

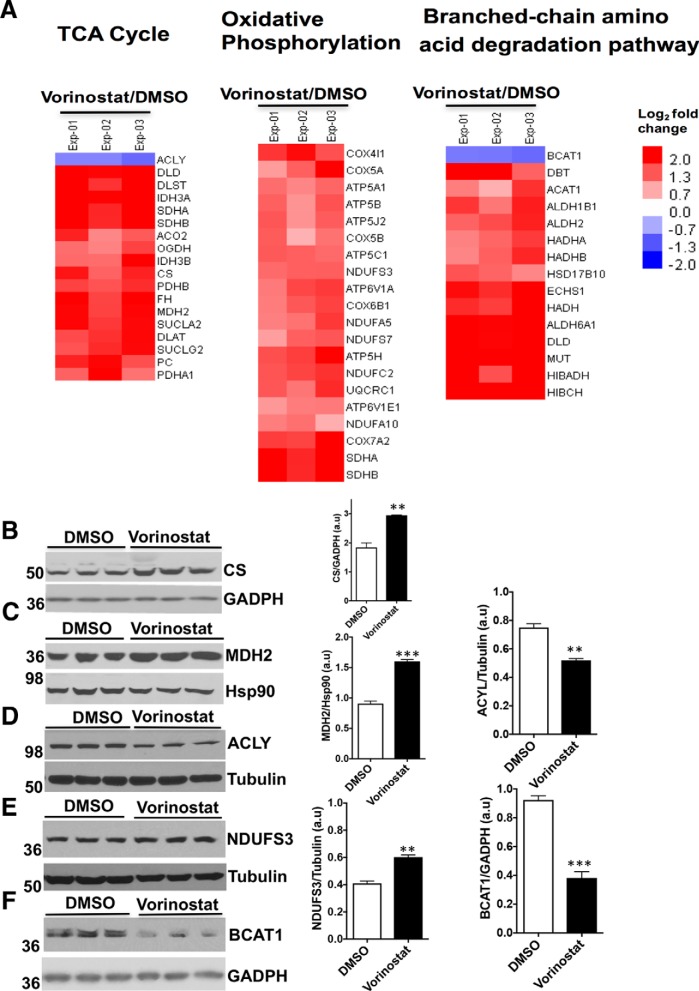

Fig. 5.

Effect of Vorinostat on the expression level of proteins in energy metabolic pathways in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. A, Heat map of differentially expressed proteins of energy metabolic pathways in DMSO or Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts quantified by TMT experiments. B–F, Western blotting of cell lysates from DMSO or Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. Cell lysates were resolved using SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with the indicated antibodies as described in Methods. The TCA cycle proteins CS (B), and MDH2 (C) were upregulated, whereas ACLY (D) was downregulated. The oxidative phosphorylation protein NDUFS3 (E) was upregulated whereas the branched-chain amino acid degradation (BCAA) pathway component BCAT1 (F) was downregulated. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Bar graph represents the relative amount of protein normalized to the loading control GADPH, Hsp90, or tubulin from three independent experiments.

Strikingly, Vorinostat treatment upregulates the expression of most of the proteins found in TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation pathways (Fig. 5A). Western blot analysis showed the expression of citrate synthase (CS), which catalyzes the synthesis of citrate from oxaloacetate and acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), and malate dehydrogenase (MDH2), which catalyzes the reversible oxidation of malate to oxaloacetate in the TCA cycle, is increased in Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 5B, and 5C). ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) catalyzes the formation of cytosolic acetyl-CoA from the substrate citrate and CoA. The product acetyl-coA serves as an important source for several biosynthetic pathways, including lipogenesis and cholesterogenesis, and acetylation through histone acetylases (HATs) (42). With Vorinostat treatment, the level of ACLY is significantly reduced in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 5D). The expression level of NDUFS3, a subunit of the Complex I in the mitochondria involved in electron transfer from NADPH to the respiratory chain, is significantly increased in Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061Tfibroblasts (Fig. 5E), perhaps reflecting an improved environment for managing oxidative stress and energy metabolism. Treatment of Vorinostat also upregulated most of the proteins in the branched-chain amino acid degradation (BCAA) pathway in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. Branched Chain Amino-Acid Transaminase 1 (BCAT1) catalyzes the reversible transamination of branched-chain alpha-keto acids to branched-chain l-amino acids and promotes the catabolism of branched chain amino acids leucine, isoleucine, and valine (43). In Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts, the expression level of BCAT1 is significantly reduced suggesting a modulation of amino acid pools impacting protein synthesis or metabolic flux pathways (Fig. 5F). Together, these studies demonstrate the impact of Vorinostat in mediating restoration or activation of energy metabolic pathways and the potential need to improve the mitochondrial function in response to NPC disease.

Lysosomal Proteins

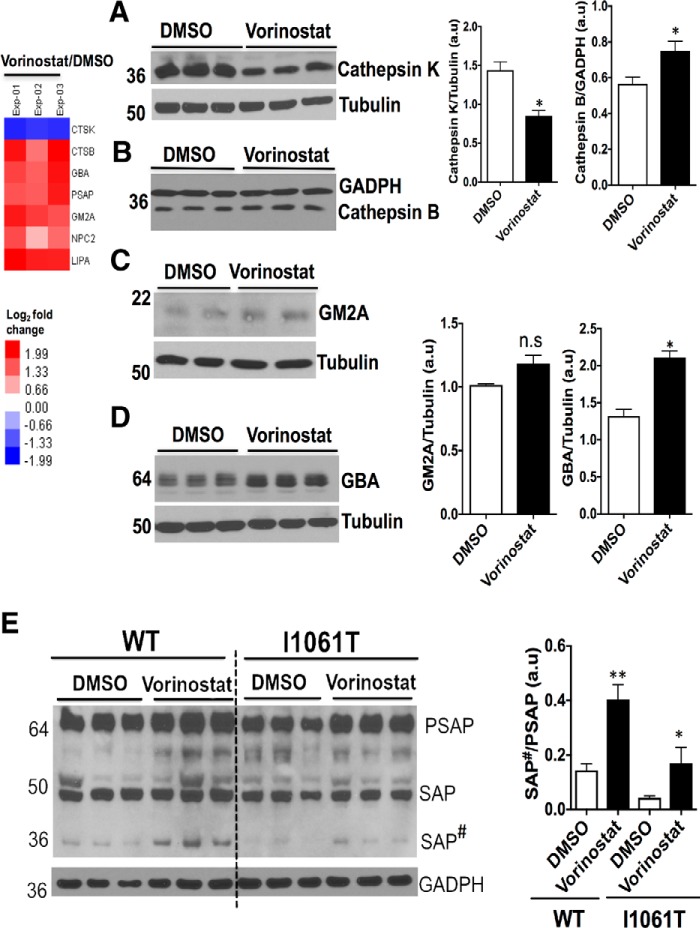

NPC disease is characterized by LE/Ly dysfunction in response to accumulation of sphingosine, glycosphingolipids, sphingomyelin and cholesterol (44–46). Moreover, cathepsin family protein expression levels and activity are severely altered in NPC disease. Cathepsins may impact the post-translational processing of lipid metabolizing enzymes (47, 48). We validated the expression level of two lysosomal cysteine proteases, cathepsin K (CTSK) and cathepsin B (CTSB). Western blot analysis revealed the downregulation of cathepsin K and the upregulation of cathepsin B in Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 6A and 6B). Although documented as being differentially expressed using TMT, GM2 ganglioside activator (GM2A) protein (49) that stimulates the enzymatic processing and degradation of glycosphingolipids in the lysosome was marginally increased with Vorinostat treatment in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts based on Western blotting (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the relative expression of β-glucocerebrosidase (GBA) and prosaposin (PSAP) exhibited statistically significant increased expression with Vorinostat treatment in WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 6D, and 6E). Mutations in the GBA and PSAP genes are responsible for Gaucher's disease raising the possibility that reduced levels in response to loss of cholesterol homeostasis contribute to disease (50). PSAP is a neurotrophic factor that promotes neurite outgrowth and neuronal development (51). PSAP exists as an unprocessed protein in brain and secretory fluids (52), but it is also a precursor for four smaller glycoproteins, saposins A, B, C, and D. The biosynthesis, processing, and targeting of precursor SAP from the ER to LE/Ly in cultured fibroblasts has been demonstrated in fibroblasts (53). Saposins activate the degradation of sphingolipids by Ly enzymes (54). PSAP level is decreased in NPCI1061T fibroblasts when compared with fibroblasts from healthy individuals (Fig. 6E). Treatment with Vorinostat increased the level of PSAP and promoted the processing of PSAP to SAP#, a intermediate forms in the NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 6E). Although, the intermediate forms of SAP# undergo proteolytic processing in the LE/Ly compartments leading to the generation of saposins A-D glycoproteins, TMT was not able to resolve which of the specific isoforms of saposins A-D were generated in response to Vorinostat. In addition, Vorinostat was found to upregulate other lysosomal proteins and downregulated apolipoprotein B (APOB), an important component of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (supplemental Fig. S5). These observations are consistent with the recent studies that Vorinostat alters liver APOB level in both Npc1−/− and Npc1nmf164 mouse model of NPC disease (55). In general, our data suggest that Vorinostat affects the differential expression of many lysosomal proteins in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts, together which may contribute to the improvement in overall LE/Ly cholesterol homeostasis. The improvement in cholesterol homeostasis might be achieved because of more efficient folding, stability and trafficking of NPC1I1061T to the LE/Ly, and/or by providing a favorable environment for rescued NPC1I1061T to function.

Fig. 6.

Vorinostat alters the expression of lysosomal proteins in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. A–D, Western blot analysis of cell lysates from DMSO- or Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. Cell lysates were resolved using SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with the indicated antibodies as described in Methods. Cathepsin K (A) was downregulated, whereas Cathepsin B (B), GM2A (C), and GBA (D) were upregulated in Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts when compared with control DMSO treated cells. E, Western blotting of cell lysates from DMSO- or Vorinostat-treated WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts using an anti-PSAP antibody. Cell lysates were separated in 4–20% Bis-Tris gradient gel and immunoblotted with rabbit anti-PSAP antibody (SAP#, Intermediate form). **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Bar graph shows the relative amount of protein normalized to the loading control GADPH or tubulin proteins from three independent experiments.

Vorinostat Enhances LIPA Expression and Activity in NPC1I1061T Fibroblasts

Lysosomal acid lipase (LIPA) is a soluble glycoprotein of 41–46 kDa synthesized in the ER and modified by acquisition of N-linked glycan chains (56). LIPA processes LDL-derived cholesteryl esters and triglycerides into free cholesterol and fatty acids, respectively, in the lumen of the Ly (57). The free cholesterol is subsequently bound by the soluble NPC2 protein and transferred to NPC1 which delivers cholesterol to the lysosomal membrane through sequential transfer to the middle lumenal and N-terminal domain of NPC1 (4, 58), referred to herein as the LIPA->NPC2->NPC1 cholesterol flow axis. Loss-of-function of LIPA because of mutations lead to the accumulation of cholesterol esters and other lipids and are known to cause the development of two major disease phenotypes: infantile-onset Wolman disease and later-onset cholesteryl ester storage disease (CESD) (59, 60). To date, over 40 LIPA disease-causing mutations have been reported in Wolman and CESD diseases (61). From the TMT analysis, there was an upregulation of LIPA in Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. Our validation study revealed that the treatment of Vorinostat leads to a statistically significant increase in the expression of LIPA in both WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 7A).

To assess the folding and trafficking pathway of LIPA in WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts, we examined the maturation of LIPA from the ER to post-ER compartments using endo H analysis. Addition of Vorinostat leads to a modest improvement in the endo H resistant glycoform of LIPA in WT cells and nearly 2-fold increase of LIPA in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 7B). Similarly, LIPA exhibits a folding and trafficking defect in HeLa-shNPC1 cells stably expressing NPC1I1061T when compared with cells expressing WT NPC1. Upon treatment with Vorinostat, LIPA showed an improvement in folding and trafficking with acquisition of increased endo H resistance in both WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 7C). Further, analysis of LIPA folding and trafficking in npc1-deficient (shNPC1) cells indicates that LIPA is targeted to the Ly independent of NPC1 protein (Fig. 7D). Given the effect of Vorinostat on the expression and folding, stability and trafficking of LIPA protein, we measured the LIPA enzymatic activity from WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblast cell homogenates. NPC1I1061T fibroblasts exhibited a significant reduction in LIPA specific activity when compared with that found in WT fibroblasts (Fig. 7E). Upon treatment with Vorinostat, LIPA specific activity was significantly increased in both WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 7F, 7G). Treatment with Orlistat, a potent inhibitor of LIPA, as expected, reduced the LIPA specific activity in both WT and NPC1I1061T fibroblasts (Fig. 7H, 7I).

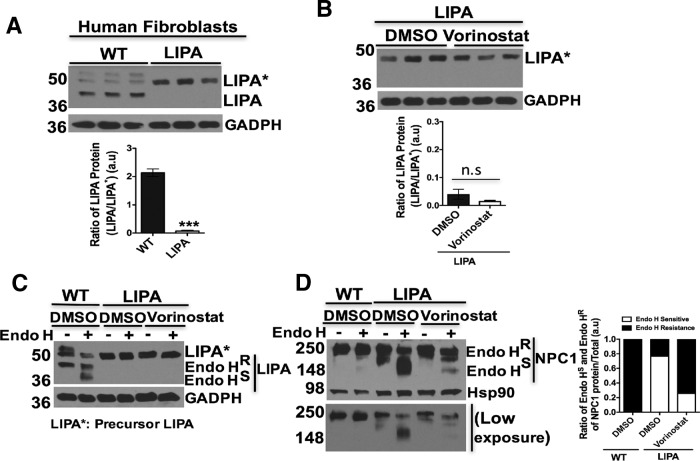

Effect of Vorinostat on LIPA Expression and Trafficking in LIPA Fibroblasts

To gain further insight into the impact of Vorinostat on LIPA on the folding, stability and/or trafficking of NPC1I1061T, we compared the levels of the LIPA polypeptide in WT and in fibroblasts with deficient LIPA activity (GM11851) derived from Wolman disease patients. The processing of mutant LIPA is deficient in LIPA fibroblasts and mostly retained in a precursor form in the ER when compared with control WT LIPA expressing fibroblasts (Fig. 8A). Upon Vorinostat treatment, we did not observe any effect on the folding, stability or trafficking of the mutant LIPA protein in LIPA fibroblasts derived from Wolman patients (Fig. 8B, 8C). In contrast, when we analyzed the effect of Vorinostat on endogenous NPC1 protein folding and trafficking in mutant LIPA expressing fibroblasts, we found that the folding, stability and trafficking of WT NPC1 protein from the ER was increased as shown by the acquisition of increased endo H-resistance when compared with the DMSO control (Fig. 8D), as was observed in WT LIPA containing fibroblasts (Fig. 8D, lane 1–2). Given the above response of WT LIPA to Vorinostat in the presence NPC1I1061T (Fig. 7B), these data raise the possibility that Vorinostat treatment improves the folding, stability, trafficking and function of LIPA in an NPC1I1061T sensitive fashion, thereby contributing to more efficient processing of LDL-derived cholesterol esters. One possibility is that this improved nascent cholesterol pool could serve as a more effective substrate for the LIPA->NPC2->NPC1 axis than the aberrantly accumulated pools in response to the absence or limiting residual NPC1I1061T function in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. Thus, our proteomic analysis suggests that Vorinostat may selectively impact endogenous LIPA function in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts to help manage cellular cholesterol homeostasis.

Fig. 8.

Impact of Vorinostat on expression and trafficking of human LIPA and NPC1 protein from LIPA mutant fibroblasts. A, Western blotting of LIPA protein from WT and LIPA mutant fibroblasts. Cell lysates were extracted, and equal amount of cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with mouse anti-LIPA antibody. GADPH was used as a loading control. Graph represents the ratio of LIPA protein (LIPA*/LIPA), ***p < 0.001. B, Western blotting of LIPA protein from DMSO or Vorinostat treated LIPA fibroblasts. LIPA fibroblast was treated with DMSO or Vorinostat (10 μm) for 72 h., cell lysates were obtained and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. GADPH was used as a loading control. Graph represents the ratio of LIPA protein (LIPA*/LIPA), n.s (no significant). C, Endo H digestion of cell lysates derived from DMSO-treated WT fibroblasts and DMSO or Vorinostat treated LIPA fibroblasts. Samples were separated in 10% SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with LIPA antibody. D, Endo H digestion of cell lysates derived from DMSO-treated WT fibroblasts and DMSO or Vorinostat treated LIPA fibroblasts. Samples were separated in 10% SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with NPC1 antibody. For equal loading control, GADPH or Hsp90 was used in the Western blotting. Bar graphs: endo H sensitive (white) or endo H resistant (black) glycoforms are quantified as percent of total NPC1 in each lane.

DISCUSSION

The pathophysiology of Niemann-Pick type C (NPC) disease is complex and incompletely understood. The NPC1I1061Tmissense variant in fibroblasts is poorly expressed and targeted for proteasomal degradation (6) disrupting the normal LIPA->NPC2->NPC1 axis of cholesterol flow in the LE/Ly, resulting in impaired cholesterol efflux and LE/Ly accumulation of cholesterol and other lipids. Given the clinical presentation of disease and its rare disease status in the population, there has been strong interest in repurposing therapeutics that are currently FDA approved for human use. These include HPβCD as a bulk phase chemical chaperone that extracts cholesterol in both cell-based, mouse, and cat models, resulting in significant restoration of function and lifespan (9, 62–64). The efficacy in model systems has been successfully translated to the clinic where HPβCD is now entering Phase IIb clinical trials because of its striking impact in arresting progression of disease (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02534844) (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02534844?term=Niemann-pick+disease&rank=23). In addition, antioxidants, δ-Tocopherol (65), the pharmacological chaperone Miglustat, that serves as a substrate reduction therapy for glycospingolipid load in disease (66, 67), and HDACis positively impact the cholesterol phenotype observed in disease (68). Previous studies have shown that Vorinostat increases the level of NPC1 (I1061T) and reduces cholesterol accumulation in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts and MEFs (15, 30), providing the basis for the current studies. Indeed, multiple studies have shown that HDACis are effective in treating inherited diseases caused by misfolding of many proteins (69, 70). For example, HDACis restore function of misfolded CFTR (ΔF508) in cystic fibrosis (71), they promote the secretion of an active form of Z-α1AT in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) (72), and prevent the premature degradation and restore the enzymatic activity of glucocerebrosidase (GBA), a LY protein that, when mutated, is responsible for Gaucher's disease (73). In a recent study, we have shown that the Vorinostat treatment restores the cholesterol storage defects in a large fraction of patient-derived NPC1 mutants (17) The exact mechanism by which Vorinostat restores cholesterol homeostasis in NPC fibroblasts remains unknown, although recent studies have shown that combining HPβCD and Vorinostat results in a significant improvement in both lifespan and cognitive function in the NPC1 (nmf164-D1005G) mouse model (18) suggesting that the forced clearance of aberrantly stored cholesterol pools in the LE/Ly by HPβCD may establish a normal LE/Ly environment for HDACi to achieve efficient function in controlling cholesterol flux.

The activity of HATs and HDACs control post-translationally the acetylation/deacetylation balance that not only manages the fate of the transcription through histones, but also for many proteins in cell—referred to as the acetylome. For example, HAT acetylates histone and relaxes chromatin, resulting in transcriptional activation of many genes. In contrast, HDACs deacetylate histones causing DNA compaction and, consequently repression of transcriptional activity. HDACi reverse compaction and thereby strongly impact the new and/or elevated expression of numerous proteins. HATs and HDACs also regulate acetylation/deacetylation of numerous non-histone proteins, including nuclear import factors, cytoskeletal proteins, and molecular chaperones and their regulated expression through heat shock response (HSR) pathways managing cytosolic proteostasis (74–76). Moreover, acetylation protects proteins from proteasomal degradation by preventing access to lysine residues for ubiquitination by E3 ubiquitin ligases (74). Thus, by preventing the activity of HDACs, HDACi's derepress the expression and/or activity of many genes that could directly or indirectly contribute to improved cellular health in NPC1I1061T disease.

To directly address the role of acetylation/deacetylation balance in NPC disease, we used a TMT-based quantitative proteomics approach to identify proteins that are significantly changed in response to treatment of fibroblasts derived from NPCI1061T patients with Vorinostat. Following data acquisition and analysis of TMT-duplex labeled samples, we quantified 2916 proteins in all three biological replicates of NPC1I1061T fibroblasts treated with Vorinostat and the vehicle control. Based on z-scores (−1 ≤ z-score ≥ 1) and BH-corrected one-sample t test p value (< 0.05), 202 proteins were observed as differentially responsive to Vorinostat. In all cases tested, Western blotting analysis matched TMT results by showing a similar trend in protein levels in response to Vorinostat compared with the vehicle control. KEGG pathway analysis showed significant enrichment of proteins involved in energy metabolism and oxidative stress in the differentially expressed data set. We also observed change in expression of proteins involved in folding, degradation and trafficking pathways as well as lipid metabolism.

Dysfunction of energy metabolism and oxidative stress pathways are among the key features underlying pathophysiology of NPC disease (39, 40). Our previous study showed that proteins associated with oxidative stress and energy metabolism were downregulated in NPC1 fibroblasts when compared with WT fibroblasts (21). Moreover, other studies have shown the alteration of oxidative stress response in the cerebellum of Npc1−/− murine model (77). In response to Vorinostat-treatment, proteins involved in these pathways were notably upregulated. This may help to counteract the oxidative stress response found in NPC1 fibroblasts because of loss of cholesterol homeostasis.

Loss of cholesterol homeostasis disrupts mitochondrial function (78). Consistent with this view, a recent study showed that fibroblasts derived from NPC1 disease patients exhibited altered mitochondrial energy metabolic pathways (39). In our study, following Vorinostat treatment, most of the differentially expressed proteins were found to be involved in energy metabolism. For example, proteins involved in metabolic pathways, such as TCA cycle, oxidative phosphorylation and others were upregulated. We validated the increased expression of three proteins associated with the energy metabolism pathway: citrate synthase (CS) and malate dehydrogenase 2 (MDH2) which catalyze the first and last step of the TCA cycle, respectively, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) which catalyzes the rate-limiting step of the oxidative pentose-phosphate pathway. ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY), that catalyzes the formation of cytosolic acetyl-CoA, has been shown to be upregulated in cancer cells and activate fatty acid synthesis (42). Following Vorinostat treatment, the expression level of ACYL is downregulated. This could impede the signaling pathways that direct the synthesis of lipids in NPC1 fibroblasts and thereby indirectly help reduce the lipid burden.

Furthermore, we have provided evidence for increased expression of proteins involved in the BCAA pathway in Vorinostat-treated NPC fibroblasts. A recent study demonstrated the altered amino acid metabolic pathways in the cerebellum of the NPC mouse model (79). The mRNA levels of both BCAT1/BCAT2, the key enzymes of glutamine/glutamate metabolism are elevated in the cerebellum of NPC1−/− -deficient mice. One possibility is that the downregulation of BCAT1 protein observed in Vorinostat-treated NPC1I1061T fibroblasts could improve the amino acid balance in NPC disease. Because HDACi, in addition to their effects on transcription, promotes the lysine acetylation of metabolic proteins and regulates their activity (19), the actual mechanism by which a new level of protein stability and/or change in enzymatic activity of key proteins influencing these metabolic pathways and perhaps other Vorinostat sensitive pathways remains to be determined (80–82). A speculative possibility is that Vorinostat acts through inhibiting HDAC and takes advantage of the coordination normally found in healthy cells to modulate the expression of a cohort of related pathways involved in energy metabolism, leading to the generation of a larger acetyl-coA pool that can provide precursors for the acetylation of proteins involved in several cellular functions impacting restoration of cholesterol homeostasis.

Lysosomes (Ly) are the primary degradative compartment of the cell and play key role in maintaining protein homeostasis in conjunction with the metabolome through mTOR. Accumulation of cholesterol because of mutation of NPC1 impairs the function of LE/Ly pathway in NPC1 disease. Very recently, studies have showed the NPC1 contributes to transfer of cholesterol across the Ly glycocalyx, a critical lysosomal glycoprotein coat that impairs cholesterol homeostasis in the absence of NPC1 (83). Another study has reported the altered expression and subcellular distribution of Ly proteins including cathepsin in the brain of npc1-deficient mice (48), possibly reflecting the generation of a maladaptive LE/Ly environment because of impairment of cholesterol homeostasis (84). The cathepsin B activity in primary fibroblasts from NPC1I1061T patients was reduced to ∼50% of control WT fibroblasts (85). With Vorinostat treatment the cathepsin B was increased along with other Ly proteins such as GBA, PSAP, GM2A, and NPC2 mediating the lipid metabolism. These findings provide evidence that Vorinostat-mediated alteration of the Ly protein pool may help to counterbalance the defective function and pathology of the LE/Ly in NPC disease.

To qualify as differentially expressed in response to Vorinostat, we only selected proteins that met our significance threshold in all three replicates (supplemental Table S2). TMT-based quantification is affected by interference from the co-eluting peptides. Hence, we have also included a separate list with proteins that either met the BH-corrected p value in all three replicates, but fulfills the Z-score threshold in only two of the replicates, or vice-versa (supplemental Table S4). Among these, our Western blot analysis confirmed the differential expression of LIPA, a lysosomal acid lipase involved in the processing of LDL-derived cholesterol ester into free cholesterol. Aberrant function of LIPA impairs the cholesterol transport through LIPA->NPC2->NPC1 axis found in lysosomes. Interestingly, studies have shown that targeting LIPA protein with small molecule compounds that directly inhibit its activity reduces the sterol accumulation in NPC1I1061T disease (23, 24). Our data, in contrast, suggest that Vorinostat may either directly or indirectly improve the folding and trafficking of LIPA to lysosomes to improve function in disease harboring NPC1 mutants, raising the possibility that Vorinostat manages an unknown balance of several LE/Ly components that favor improved cholesterol homeostasis at elevated levels reflecting a more global modulation of Ly content through community interactions.

Our explorative study with TMT-based quantitative proteomics identified a collective of differentially expressed proteins in NPCI1061T fibroblasts, thus providing the first global perspective of changes in the cellular processes in response to Vorinostat treatment that could be responsible in mitigating the disease pathology. Although we have focused on protein abundance, additional studies focused on identifying proteins whose functional activity, cellular localization, and/or posttranslational modifications through acetylation/deacetylation are affected by Vorinostat will be also useful. Moreover, comparing the interactome of NPC1I1061T fibroblasts in the vehicle control and Vorinostat-treated conditions will help to understand its mode of action in restoring cholesterol homeostasis, similar to the impact of interactome analysis of the dynamics of the CFTR (ΔF508) response to Vorinostat that can restore function in cystic fibrosis (86). We anticipate that quantitative analysis of the proteome and interactome changes in response to Vorinostat using diverse mass spectrometry approaches may lead to the identification of new therapeutic targets and/or improved specificity of HDACi (86) that target unique features of the read-write-erase program that contributes uniquely to the acetylation/deacetylation balance that can be altered to improve the function of NPC1 variants.

CONCLUSION

NPC is a rare, neurodegenerative and lipid storage disorder with no effective treatment. Vorinostat is currently in clinical trials for the treatment of adult NPC patients, although it has poor blood-barrier penetrance so that its impact on NPC disease progression in the patient could be limited. A supplementation strategy with HDACi linked to current HPβCD intrathecal delivery protocols may be an option (18). In the case of NPC1, our current understanding of the impact of Vorinostat is that it increases the expression of the I1061T NPC1 variant and improves its trafficking, both events that lead to restoration of cholesterol homeostasis (15, 30). Thus, identification of additional proteins affected by Vorinostat treatment will be of potential value in understanding more precisely how Vorinostat mediates restoration of cholesterol homeostasis. Using TMT-based quantitative proteomics, we identified 202 differentially expressed proteins in NPC fibroblasts treated with Vorinostat. These proteins map to diverse compartments, such as mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi, and LE/Ly, all of which may contribute to the Vorinostat response. The proteins are also involved in diverse biological processes. For example, these include metabolic, protein folding, and lipid homeostasis pathways representatives of which, we validated by Western blot analysis. In addition, we have shown that Vorinostat upregulates LIPA, a protein responsible for Wolman disease, and facilitates its folding and trafficking to the LE/Ly compartments in NPC1I1061T fibroblasts. In conclusion, targeting differentially expressed proteins revealed by our study with Vorinostat may provide a useful framework for a broader range of therapeutic intervention strategies for treatment of NPC disease in the clinic.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD006005 (Project Webpage: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD006005; FTP Download: ftp://ftp.pride.ebi.ac.uk/pride/data/archive/2017/09/PXD006005).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author contributions: K.S., N.R., J.R.Y., and W.E.B. designed research; K.S. and N.R. performed research; K.S., N.R., M.L., J.R.Y., and W.E.B. contributed new reagents or analytic tools; K.S., N.R., and M.L. analyzed data; K.S., N.R., and M.L. wrote the paper; J.R.Y. and W.E.B. served as project supervisors for all aspects of the study.

* This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants P41 GM103533 and R01 HL079442-09 (to J.R.Y); the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation (APMRF), SOARS, NIH 1P01 AG049665-01, 5R01 DK051870-19, and 5R01 HL079442-10 (to W.E.B). K.S. was supported by both APMRF and a National Niemann-Pick Disease Foundation (NNPDF) Peter Pentchev Fellowship.

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- NPC1

- Niemann-Pick Type C1

- TMT

- Tandem Mass Tags

- SAHA

- Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid

- HDAC

- Histone deacetylase

- HDACi

- Histone deacetylase inhibitor

- LIPA

- Lysosomal Acid Lipase

- LE

- Late endosomes

- Ly

- Lysosomes

- ER

- Endoplasmic Reticulum

- ERAD

- ER-associated degradation

- WT

- Wild-type

- HPβCD

- Hydroxyl-propyl-β-cyclodextrin

- TCF

- Triple combination formulation

- PEG

- Polyethylene glycol

- MudPIT

- Multidimensional protein identification technology

- EndoH

- Endoglycosidase H

- KEGG

- Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- FKBP10

- FK506 binding protein 10

- GBA

- β-glucocerebrosidase

- GalNAc

- N-acetylgalactosamine

- TRAP1

- Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated protein 1

- G6PD

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- CS

- Citrate synthase

- MDH2

- Malate dehydrogenase

- ACLY

- ATP citrate lyase

- BCAA

- Branched-chain amino acid

- BCAT1

- Branched Chain Amino-Acid Transaminase 1

- CTSB

- Cathepsin B

- CTSK

- Cathepsin K

- GM2A

- GM2 ganglioside activator

- PSAP

- Prosaposin

- APOB

- Apolipoprotein

- LDL

- Low-density lipoprotein

- CESD

- Cholesteryl ester storage disease

- AATD

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

- HAT

- Histone acetyltransferase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Carstea E. D., Morris J. A., Coleman K. G., Loftus S. K., Zhang D., Cummings C., Gu J., Rosenfeld M. A., Pavan W. J., Krizman D. B., Nagle J., Polymeropoulos M. H., Sturley S. L., Ioannou Y. A., Higgins M. E., Comly M., Cooney A., Brown A., Kaneski C. R., Blanchette-Mackie E. J., Dwyer N. K., Neufeld E. B., Chang T. Y., Liscum L., Strauss J. F. 3rd, Ohno K., Zeigler M., Carmi R., Sokol J., Markie D., O'Neill R. R., van Diggelen O. P., Elleder M., Patterson M. C., Brady R. O., Vanier M. T., Pentchev P. G., and Tagle D. A. (1997) Niemann-Pick C1 disease gene: homology to mediators of cholesterol homeostasis. Science 277, 228–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vanier M. T. (2015) Complex lipid trafficking in Niemann-Pick disease type C. J. Inherited Metabolic Dis. 38, 187–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vanier M. T., and Millat G. (2003) Niemann-Pick disease type C. Clin. Gen. 64, 269–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kwon H. J., Abi-Mosleh L., Wang M. L., Deisenhofer J., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S., and Infante R. E. (2009) Structure of N-terminal domain of NPC1 reveals distinct subdomains for binding and transfer of cholesterol. Cell 137, 1213–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Runz H., Dolle D., Schlitter A. M., and Zschocke J. (2008) NPC-db, a Niemann-Pick type C disease gene variation database. Human Mutation 29, 345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gelsthorpe M. E., Baumann N., Millard E., Gale S. E., Langmade S. J., Schaffer J. E., and Ory D. S. (2008) Niemann-Pick type C1 I1061T mutant encodes a functional protein that is selected for endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation due to protein misfolding. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8229–8236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nakasone N., Nakamura Y. S., Higaki K., Oumi N., Ohno K., and Ninomiya H. (2014) Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of Niemann-Pick C1: evidence for the role of heat shock proteins and identification of lysine residues that accept ubiquitin. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 19714–19725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ottinger E. A., Kao M. L., Carrillo-Carrasco N., Yanjanin N., Shankar R. K., Janssen M., Brewster M., Scott I., Xu X., Cradock J., Terse P., Dehdashti S. J., Marugan J., Zheng W., Portilla L., Hubbs A., Pavan W. J., Heiss J., Vite C. H., Walkley S. U., Ory D. S., Silber S. A., Porter F. D., Austin C. P., and McKew J. C. (2014) Collaborative development of 2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin for the treatment of Niemann-Pick type C1 disease. Current Topics Med. Chem. 14, 330–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vite C. H., Bagel J. H., Swain G. P., Prociuk M., Sikora T. U., Stein V. M., O'Donnell P., Ruane T., Ward S., Crooks A., Li S., Mauldin E., Stellar S., De Meulder M., Kao M. L., Ory D. S., Davidson C., Vanier M. T., and Walkley S. U. (2015) Intracisternal cyclodextrin prevents cerebellar dysfunction and Purkinje cell death in feline Niemann-Pick type C1 disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 276ra226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu B., Turley S. D., Burns D. K., Miller A. M., Repa J. J., and Dietschy J. M. (2009) Reversal of defective lysosomal transport in NPC disease ameliorates liver dysfunction and neurodegeneration in the npc1-/- mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 2377–2382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pontikis C. C., Davidson C. D., Walkley S. U., Platt F. M., and Begley D. J. (2013) Cyclodextrin alleviates neuronal storage of cholesterol in Niemann-Pick C disease without evidence of detectable blood-brain barrier permeability. J. Inherited Metabolic Dis. 36, 491–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosenbaum A. I., Zhang G., Warren J. D., and Maxfield F. R. (2010) Endocytosis of beta-cyclodextrins is responsible for cholesterol reduction in Niemann-Pick type C mutant cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 5477–5482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ohgane K., Karaki F., Dodo K., and Hashimoto Y. (2013) Discovery of oxysterol-derived pharmacological chaperones for NPC1: implication for the existence of second sterol-binding site. Chem. Biol. 20, 391–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohgane K., Karaki F., Noguchi-Yachide T., Dodo K., and Hashimoto Y. (2014) Structure-activity relationships of oxysterol-derived pharmacological chaperones for Niemann-Pick type C1 protein. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24, 3480–3485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pipalia N. H., Cosner C. C., Huang A., Chatterjee A., Bourbon P., Farley N., Helquist P., Wiest O., and Maxfield F. R. (2011) Histone deacetylase inhibitor treatment dramatically reduces cholesterol accumulation in Niemann-Pick type C1 mutant human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 5620–5625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Munkacsi A. B., Chen F. W., Brinkman M. A., Higaki K., Gutierrez G. D., Chaudhari J., Layer J. V., Tong A., Bard M., Boone C., Ioannou Y. A., and Sturley S. L. (2011) An “exacerbate-reverse” strategy in yeast identifies histone deacetylase inhibition as a correction for cholesterol and sphingolipid transport defects in human Niemann-Pick type C disease. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 23842–23851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pipalia N. H., Subramanian K., Mao S., Ralph H., Hutt D. M., Scott S. M., Balch W. E., and Maxfield F. R. (2017) Histone deacetylase inhibitors correct the cholesterol storage defect in most NPC1 mutant cells. J. Lipid Res. 58, 695–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alam M. S., Getz M., and Haldar K. (2016) Chronic administration of an HDAC inhibitor treats both neurological and systemic Niemann-Pick type C disease in a mouse model. Sci Transl. Med. 8, 326ra323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Choudhary C., Weinert B. T., Nishida Y., Verdin E., and Mann M. (2014) The growing landscape of lysine acetylation links metabolism and cell signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 536–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rauniyar N., and Yates J. R. 3rd. (2014) Isobaric labeling-based relative quantification in shotgun proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 13, 5293–5309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rauniyar N., Subramanian K., Lavallee-Adam M., Martinez-Bartolome S., Balch W. E., and Yates J. R. 3rd. (2015) Quantitative proteomics of human fibroblasts with I1061T mutation in Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1) protein provides insights into the disease pathogenesis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 14, 1734–1749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Washburn M. P., Wolters D., and Yates J. R. 3rd. (2001) Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 242–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rosenbaum A. I., Rujoi M., Huang A. Y., Du H., Grabowski G. A., and Maxfield F. R. (2009) Chemical screen to reduce sterol accumulation in Niemann-Pick C disease cells identifies novel lysosomal acid lipase inhibitors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 1155–1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosenbaum A. I., Cosner C. C., Mariani C. J., Maxfield F. R., Wiest O., and Helquist P. (2010) Thiadiazole carbamates: potent inhibitors of lysosomal acid lipase and potential Niemann-Pick type C disease therapeutics. J. Med. Chem. 53, 5281–5289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loftus S. K., Morris J. A., Carstea E. D., Gu J. Z., Cummings C., Brown A., Ellison J., Ohno K., Rosenfeld M. A., Tagle D. A., Pentchev P. G., and Pavan W. J. (1997) Murine model of Niemann-Pick C disease: mutation in a cholesterol homeostasis gene. Science 277, 232–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Davies J. P., and Ioannou Y. A. (2000) Topological analysis of Niemann-Pick C1 protein reveals that the membrane orientation of the putative sterol-sensing domain is identical to those of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase and sterol regulatory element binding protein cleavage-activating protein. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 24367–24374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vanier M. T. (2010) Niemann-Pick disease type C. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 5, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Millat G., Marcais C., Rafi M. A., Yamamoto T., Morris J. A., Pentchev P. G., Ohno K., Wenger D. A., and Vanier M. T. (1999) Niemann-Pick C1 disease: the I1061T substitution is a frequent mutant allele in patients of Western European descent and correlates with a classic juvenile phenotype. Am. J Human Gen. 65, 1321–1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]