Abstract

The intercellular communication between leukemia cells and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) plays more important role in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) than we previously understood. Recently, we found that microvesicles released from human leukemia cell line K562 (K562-MVs) containing BCR-ABL1 mRNA malignantly transformed normal hematopoietic transplants. Here, we investigated whether K562-MVs contribute to the transformation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs). We showed that K562-MVs could be integrated into co-cultured normal BM-MSCs and dose-dependently enhanced the proliferation of BM-MSCs. Meanwhile, K562-MVs (400 ng/mL) significantly increased the expression of BCR-ABL1 in these BM-MSCs, accompanied by the enhanced secretion of TGF-β1. These BM-MSCs in turn could trigger the TGF-β1-dependent proliferation of K562 cells. Moreover, we confirmed the presence of BCR-ABL1 in circulating MVs from 11 CML patients. Compared to the normal BM-MSCs, the BM-MSCs from CML patients more effectively increased the BCR-ABL1 expression and TGF-β1 secretion in K562 cells as well as the proliferation of K562 cells. Our findings enrich the mechanisms involved in the interaction between leukemia cells and BM-MSCs and provide novel ways to monitor minimal residual disease and worthwhile approaches to treat CML.

Keywords: chronic myeloid leukemia, microvesicle, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell, BCR-ABL1, TGF-β1

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a hematological malignancy originating from a primitive hematopoietic cell transformed by the BCR-ABL1 oncogene, which results from a reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 9 and 221,2. Currently, the BCR-ABL1 inhibitor (TKI) imatinib, as well as other new drugs, is highly effective in the treatment of CML, resulting in major reductions in BCR-ABL1 transcript levels in most patients with chronic-phase CML. However, due to the presence of minimal residual disease (MRD), as measured by copies of BCR-ABL1 transcripts, complete eradication of the disease has not been possible, and cessation of TKI therapy leads to disease recurrence in most CML patients1,3,4,5,6,7,8.

It is becoming increasingly evident that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) associated with tumors are recruited to tumors and play an important role in shaping the nature of both solid and hematological malignancies9,10. Recent studies have revealed a more important role for the bone marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs) in the sustained MRD and disease progression of CML than previously understood1,3,6,11,12. Jin et al12 found that the up-regulation of CXCR4 by a TKI promotes the migration of CML cells to bone marrow stroma, causing G0-G1 cell cycle arrest and ensuring the survival of quiescent CML progenitor cells. Zhang et al1 reported that when co-cultured with human BM-MSCs, the apoptosis of CML stem/progenitor cells is significantly inhibited and survival is increased following TKI exposure. However, the mechanisms underlying the crosstalk between leukemia cells and BM-MSCs have not been elucidated.

In the last two decades, the intercellular transfer of extracellular vesicles (EVs) has emerged as a novel mechanism for intercellular communication13. Generally, EVs are mainly reported as two different types, exosomes and microvesicles (MVs) (also called shedding vesicles, shedding microvesicles, or microparticles)14. Irrespective of their origin, MVs are circular membrane fragments retaining the characteristics of the parental cell, whereas exosomes are more homogeneous and smaller than MVs with sizes ranging from 30 to 120 nm and have an endosomal origin15. It is becoming increasingly recognized that one of the features of tumor biology involves human cancer cells releasing EVs that can then influence the surrounding cells. Tumor cell-derived EVs can horizontally transfer active molecules to target cells, inducing epigenetic changes, gene regulation, signal transduction and tumor cell migration and adhesion, reflecting the special potential of tumor cells for survival and expansion13,16,17,18,19.

In CML, the exosomes released by K562, a CML cell line, were reported to play a key role in leukemia-to-endothelial cell communication and to promote angiogenesis in a src-dependent fashion20,21; Corrado et al reported that CML exosomes stimulate BM stromal cells to produce IL-8, which modulates the leukemia cell malignant phenotype22; it was also reported that BCR-ABL1 DNA was transferred from injected K562-EVs and induced partial CML characteristics in rats23. Few reports have focused on the role of K562-MVs. We recently found that K562-MVs contain BCR-ABL1 transcripts and fully transform normal hematopoietic transplant cells into leukemia cells24. Here, we provide data indicating that these BCR-ABL1-positive K562-MVs can activate BM-MSCs, which in turn secrete TGF-β1 to promote the proliferation of leukemia cells.

Materials and methods

Patient characteristics

Patients (n=14) with newly diagnosed CML in the initial chronic phase (as verified by morphology, molecular methods and cytogenetics) were included for the present study. Primary CML BM-MSCs (LMSCs) and circulating MVs were obtained from the bone marrow of three patients and peripheral serum of eleven patients, respectively. The included CML patients were diagnosed at our institute from January 2011 to April 2017, and none had any TKI treatments prior to the study. The demographics of the patients are shown in Table 1. For the isolation of non-leukemia BM-MSCs (NMSCs), bone marrow from donors without leukemia but with benign hematological disorders (n=18; 7 with iron deficiency anemia, 10 with immunothrombocytopenia, and 1 with leukocytopenia) was obtained. Among them, 10 were female, 8 were male, and the median age was 37 (range, 22-49) years. According to the Declaration of Helsinki and approval by the Ethics Committee of Union Hospital, samples were obtained after each of the patients and the donors had presented provided informed consent.

Table 1. Presenting features of patients with CML at diagnosis and sampling.

| Patient | Age | Sex | Diagnosis time (month/year) | Sampling time (month/year) | Treatment prior tosampling | Immature Neutrophils (%) | Diagnosis | Ph+ (%) | BCR-ABL1a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation of MVs | |||||||||

| 1 | 32 | M | 8 / 2011 | 9 / 2011 | Noneb | 93 | CML-CPc | 98 | + |

| 2 | 26 | F | 8 / 2011 | 9 / 2011 | None | 91 | CML-CP | 95 | + |

| 3 | 14 | F | 1 / 2011 | 11 / 2011 | Hud | 90 | CML-CP | NAe | + |

| 4 | 19 | M | 1 / 2011 | 1 / 2012 | Hu | 97 | CML-CP | 100 | + |

| 5 | 32 | F | 12 / 2011 | 1 / 2012 | None | 99 | CML-CP | 100 | 0.411 |

| 6 | 35 | M | 12 / 2011 | 1 / 2012 | None | 93 | CML-CP | 100 | 0.451 |

| 7 | 42 | M | 2 / 2012 | 3 / 2012 | None | 56 | CML-CP | 78 | 0.209 |

| 8 | 13 | F | 3 / 2012 | 3 / 2012 | None | 94 | CML-CP | 100 | + |

| 9 | 45 | F | 3 / 2012 | 3 / 2012 | None | 80 | CML-CP | 100 | + |

| 10 | 19 | M | 2 / 2012 | 4 / 2012 | Hu | 94 | CML-CP | 100 | + |

| 11 | 40 | M | 3 / 2012 | 4 / 2012 | None | 99 | CML-CP | 100 | + |

| Isolation of BM-MSCs | |||||||||

| 1 | 41 | M | 3 / 2012 | 3 / 2012 | None | 98 | CML-CP | 100 | + |

| 2 | 46 | F | 4 / 2012 | 4 / 2012 | None | 96 | CML-CP | 97 | + |

| 3 | 29 | M | 4 / 2012 | 4 / 2012 | None | 98 | CML-CP | 100 | + |

| 4 | 22 | F | 3 / 2017 | 3 / 2017 | None | 91 | CML-CP | 97 | 0.653 |

| 5 | 36 | F | 3 / 2017 | 3 / 2017 | None | 95 | CML-CP | 96 | 0.524 |

| 6 | 43 | M | 4 / 2017 | 4 / 2017 | None | 96 | CML-CP | 98 | 0.412 |

aBCR-ABL gene was detected for all of the patients by reverse transcription PCR (+/−) or real-time quantitative PCR.

bNone means no treatments prior to diagnosis.

cCML-CP, chronic phase of CML.

dHu stands for treatment of oral hydroxyurea.

eNo data available.

Cell culture

Both NMSCs and LMSCs were cultured and selected in plastic flasks. MSCs were validated and used at the second to third passage, as previously described25,26. The human leukemia cell lines K562 and KG-1 were purchased from the China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC, Wuhan, China) and American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA), respectively, and were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere (v/v) in culture flasks.

Isolation of MVs from CML sera and K562 cell supernatant

Following approval by the Ethics Committee of Union Hospital and according to the Declaration of Helsinki, 10 mL of peripheral venous blood was extracted from each of the eleven included patients via the median cubital vein for the isolation of MVs as reported previously19. The plasma samples were centrifuged at 2500×g for 20 min (repeated two or more times) to remove platelets and cellular debris. The platelet-free plasma was then centrifuged at 16 000×g for 1 h at 4 °C to precipitate the MVs. After washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the MVs were resuspended in PBS and stored at 4 °C for characterization. The K562-MVs were also isolated as described in our previous protocol24,27. The protein of the prepared MVs was quantified using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad Labarotories, Hercules, CA, USA) as reported previously18, and the concentrations of MVs used in the present study were defined with the protein content. All the centrifugations were performed at 4 °C, and the isolated MVs were stored in PBS at -20 °C until experiments.

Analysis of K562-MVs by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and Western blotting

For the validation of K562-MVs, the characteristics of K562-MVs were detected by TEM (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) as previously described24. For the detection of BCR-ABL1 and TGF-β1 proteins, each K562-MV or cell fraction equivalent to 20 μg of protein was extracted and prepared as previously described18,28. The protein samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST (0.05% Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline) for 1 h, followed by incubation with monoclonal c-ABL antibodies (Abcam, 1:1000) or TGF-β1 antibodies (Boster, Wuhan, China) overnight at 4 °C. The blots were developed using a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-human secondary antibody (1:500) and a chemiluminescent detection kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

To examine the interaction between K562-MVs and NMSCs, confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed as previously reported27. Briefly, K562-MVs were stained with 1 μmol/L PKH26 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), a phospholipid dye, following the manufacturer's instructions. NMSCs were incubated with 400 ng/mL PKH26-stained K562-MVs at 37 °C for 0, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h, respectively. The cells on the coverslips were washed with PBS three times, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, counterstained with DAPI (Beyotime, China), a classic nuclear counterstain for immunofluorescence microscopy, and visualized by confocal microscopy (NikonA1Si, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) after treatment with an anti-fluorescein quencher.

Cell proliferation assay

Briefly, to evaluate the proliferation of NMSCs treated with K562-MVs (K562-MSCs), NMSCs (1×105/mL) were seeded onto each well of a 96-well microplate in a final volume of 100 μL and were cultured overnight at 37 °C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere (v/v). Next, 100 μL of K562-MVs were added at various final concentrations of 50, 100, 200, 400, 800 and 1000 ng/mL, respectively, and were subsequently cultured for another 72 h. Next, MTT (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was added to the cells to a final concentration of 0.05%, followed by incubation for another 3 h. Finally, the medium was removed and replaced with 50 μL of DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), and the plates were shaken for 3 min. The optical density (OD) of each well was determined using a microplate reader at a wavelength of 490 nm. To analyze the proliferation of K562 cells (1×105/mL, 100 μL) co-cultured with NMSCs, K562-MSCs or LMSCs (1×106/mL, 100 μL) or their supernatants for 24 h, the modified MTT test with a Cell Counting Kit (CCK-8, Zoman, China) was used as instructed. Briefly, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated for another 3 h, and the OD of each well was determined using a microplate reader at a wavelength of 450 nm. The percentage of viability was calculated from the OD value of treated cells normalized by the OD value of control cells. The data represented the mean±SEM of at least three independent experiments.

Cytogenetic analysis

Before harvest, NMSCs at passage 2 were incubated with K562-MVs at 37 °C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere (v/v) flask. Next, these K562-MSCs were fixed and spread following standard procedures, and metaphase cells were Q-banded and karyotyped as previously described26.

Quantitation of messenger RNA

RNA of K562-MVs, NMSCs, K562-MSCs, and LMSCs was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and a 5-μL RNA sample was used for the generation of cDNA using a ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays were performed using SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM (Takara, Otsu, Japan) and a real-time PCR system (ABI 7500, Applied Biosystems, USA). The primers (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were designed as follows: β-actin (285 bp), 5′-AGCGAGCATCCCCCAAAGTT-3′ (F) and 5′-GGGCACGAAGGCTCATCATT-3′ (R); TGF-β1 (182 bp), 5′-TGCTTCAGCTCCACAGAGAA-3′ (F) and 5′-TGGTTGTAGAGGGCAAGGAC-3′ (R); and BCR-ABL1 (179 bp), 5′-GATGCTGACCAACTCGTGTG-3′ (F) and 5′-GTTGGGGTCATTTTCACTGG-3′ (R). The amplification conditions consisted of an initial progressive incubation at 94 °C for 4 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 30 cycles of 54 °C for 30 s and 30 cycles of 72 °C for 25 s. Quantitation was performed using the comparative CT method, with β-actin as the normalization gene.

ELISA

ELISA was performed according to the manual of the ELISA kit (RayBiotech, Inc, Norcross, GA, USA) to detect human TGF-β1 in conditioned medium, secreted by the NMSCs, K562-MSCs or LMSCs.

Statistical analysis

The results are shown as the mean±SEM of at least three independent experiments. All of the data were analyzed using Student's t test and/or one-way ANOVA utilizing SPSS10.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA), taking a P value <0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

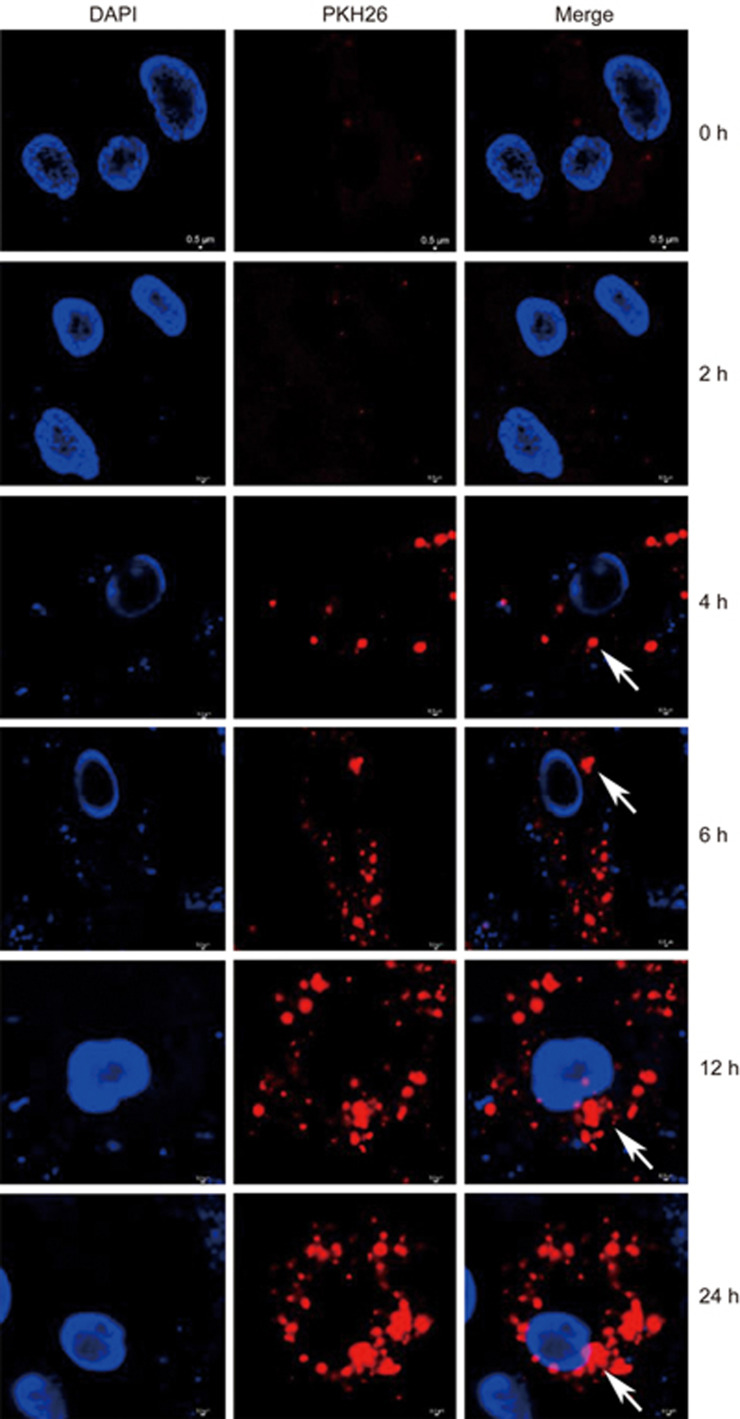

K562-MVs are integrated into BM-MSCs

Because we found that the K562-MVs initiated malignant transformation of normal hematopoietic transplants24, we next focused on the role of BM-MSCs as key microenvironment cells in CML3,5,11 and investigated whether and how K562-MVs affected the biological characteristics of BM-MSCs. K562-MVs had been validated in our previous study24. In the present study, they were additionally validated as positive for BCR-ABL1 protein, as shown in Supplementary Figure S1, and the level was substantially higher in K562-MVs than in K562 cells. MVs have been reported to be internalized by the target cells29; therefore, we used K562-MVs to treat NMSCs and observed whether K562-MVs could be incorporated into these normal BM-MSCs. As shown in Figure 1, under confocal microscopy, after 2 h of co-incubation of the NMSCs with K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL, PKH26-labeled K562-MVs were found to be internalized into NMSCs, which increased over time, and appeared around the DAPI-labeled nuclei of NMSCs after 6 h. These results show the integration of K562-MVs into NMSCs.

Figure 1.

Incorporation of K562-MVs into BM-MSCs. BM-MSCs were grown in 96-well plates for 24 h, and then PKH26-stained K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL were added. After 2, 4, 6, 12, 18 and 24 h of co-culture, the incorporation of K562-MVs into BM-MSCs with nuclei counterstained by DAPI was observed. Arrows show PKH26-stained K562-MVs (red) within the cytoplasm of BM-MSCs, around DAPI-labeled nuclei (blue), indicating the incorporation of K562-MVs into BM-MSCs. Stained cells and MVs were imaged using a confocal microscope (NikonA1Si, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) after treatment with an anti-fluorescein quencher.

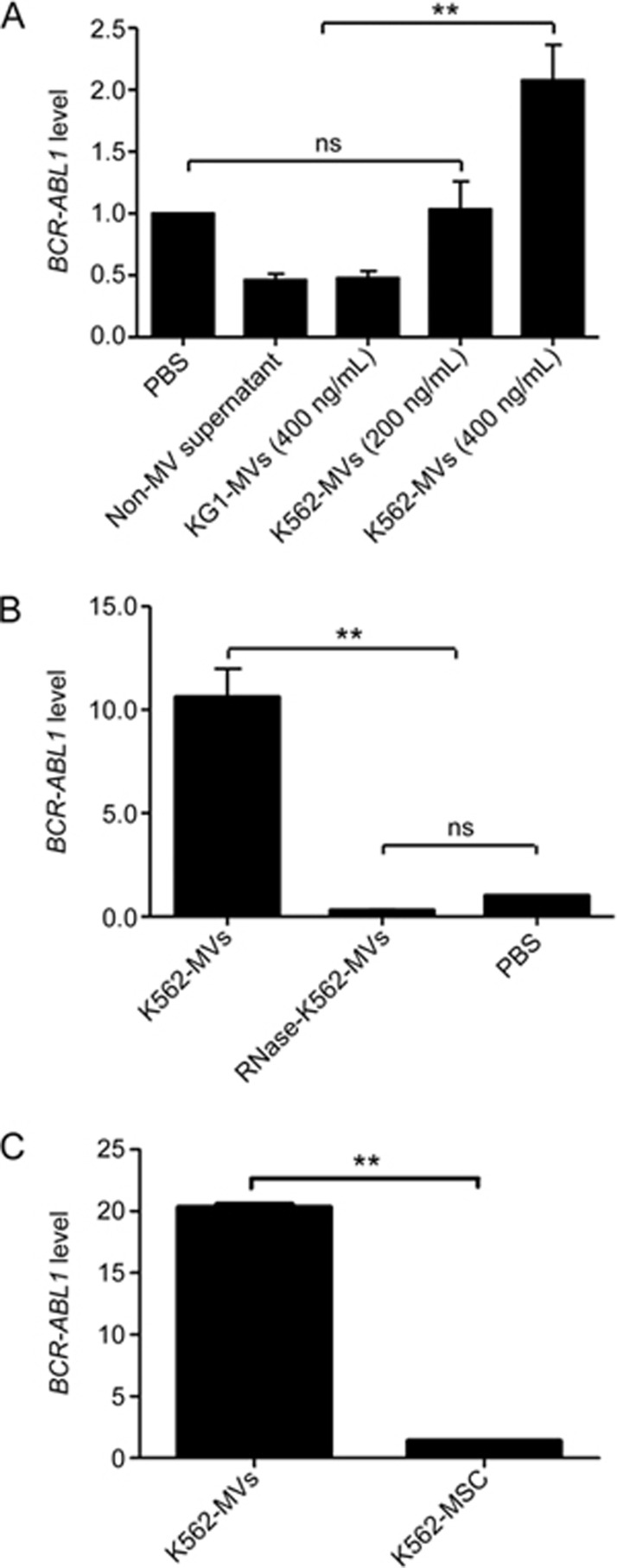

RNA cargo of K562-MVs induces BM-MSCs to express BCR-ABL1

It is well known that MVs contain a variable spectrum of molecules, whose pattern specifically reflects that of the parental cells16,17,30, and the horizontal and non-infectious transfer of nucleic acids via MVs between highly specialized cells is especially attractive to many studies15,17,31. We previously confirmed that BCR-ABL1, the hallmark and key regulator in the pathogenesis of CML32, is expressed by K562-MVs24. Thus, we determined whether K562-MV-containing BCR-ABL1 could be transferred to NMSCs. MVs released by KG1 leukemia cells (KG1-MVs at 400 ng/mL and negative for BCR-ABL1), PBS and non-MV supernatants were designed as negative controls, and K562-MVs at 200 or 400 ng/mL were used to treat NMSCs for 72 h to investigate whether BCR-ABL1-postive K562-MVs could induce NMSCs to express BCR-ABL1. We found that K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL educated MSCs to express BCR-ABL1, but those at 200 mg/mL failed (Figure 2A). To determine whether the induced expression of BCR-ABL1 was caused by the packed BCR-ABL1 within the K562-MVs, we additionally used 1 U/mL RNase (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) to treat K562-MVs for 3 h at 37 °C, and then the reaction was stopped by ultracentrifugation at 13 000×g for 1 h at 4 °C to discard the supernatant. This treatment was reported to digest the RNA content of MVs and abolish their functions via transferred RNA to receipt cells33. It was shown that RNase-treated K562-MVs failed to induce NMSCs to express BCR-ABL1, indicating that the RNA cargo of K562-MVs was responsible for the expression of BCR-ABL1 by K562-MSCs (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

K562-MVs induce BM-MSCs to express BCR-ABL1 via an RNA cargo. KG1-MVs at 400 ng/mL and negative for BCR-ABL1 (KG1-MVs), PBS, non-MV supernatant, and K562-MVs at 200 or 400 ng/mL were used to treat BM-MSCs for 72 h. (A) The detected BCR-ABL1 mRNA of K562-MSCs is shown for negative controls and the K562-MV groups. n=6; nsP>0.05; **P<0.01. (B) The detected BCR-ABL1 mRNA of K562-MSCs in which K562-MVs were pretreated with RNase (1 U/mL) for 3 h at 37 °C, and the PBS group served as a control. (C) Comparison of the level of BCR-ABL1 mRNA between K562-MVs and K562-MSCs. n=5, nsP>0.05; **P<0.01. Bars, SD. K562-MVs represent the K562-MSCs transfected with K562-MVs in panel A but themselves in panel C.

K562-MVs stimulate BM-MSCs to proliferate and horizontally transfer BCR-ABL1 to BM-MSCs

To further investigate whether the expressed BCR-ABL1 in K562-MSCs was endogenous or exogenous, NMSCs (1×104 cell/well) were cultivated with K562-MVs at various concentrations of 50–1000 ng/mL on 96-well culture plates for 72 h. First, it was shown that K562-MVs at 200–1000 ng/mL significantly promoted NMSCs to proliferate (Figure 3A). Interestingly, the proliferative effect of K562-MVs at 800 ng/mL on NMSCs was not significantly different from that of K562-MVs at 1000 ng/mL (P>0.05) and reached the highest level, suggesting that the effect of K562-MVs at 800 ng/mL on NMSCs reached the upper limit. Next, we investigated whether K562-MVs cause NMSCs to form abnormal chromosomes to determine whether the K562-MV-induced BCR-ABL1 expression in K562-MSCs was endogenous or exogenous. Previously, we and others confirmed that LMSCs do not harbor the Philadelphia chromosome26,31,34,35. In the present study, we found that K562-MVs at 800 ng/mL for 72 h did not lead to the formation of the Philadelphia chromosome in the K562-MSCs (Figure 3B), suggesting that BCR-ABL1 expressed by K562-MSCs originated not from formed t(9;22) but from the transferred BCR-ABL1 from K562-MVs. Together, our data indicate that K562-MVs horizontally transfer BCR-ABL1 to NMSCs and efficiently educated NMSCs to be K562-MSCs with a greater capacity to proliferate.

Figure 3.

BCR-ABL1 is exogenously expressed by K562-MV-MSCs with enhanced proliferation. (A) BM-MSCs treated with different concentrations of K562-MVs from 0 to 1000 ng/mL, and cell proliferative activity was observed. BM-MSCs treated with K562-MVs at 200 to 1000 ng/mL show enhanced proliferation with the compared results shown as nsP>0.05; **P<0.01; n=6. Bars, SD. (B) Chromosomal analysis of BM-MSCs treated with K562-MVs at 800 ng/mL for 72 h. No formed aberrant chromosomes can be observed, n=3.

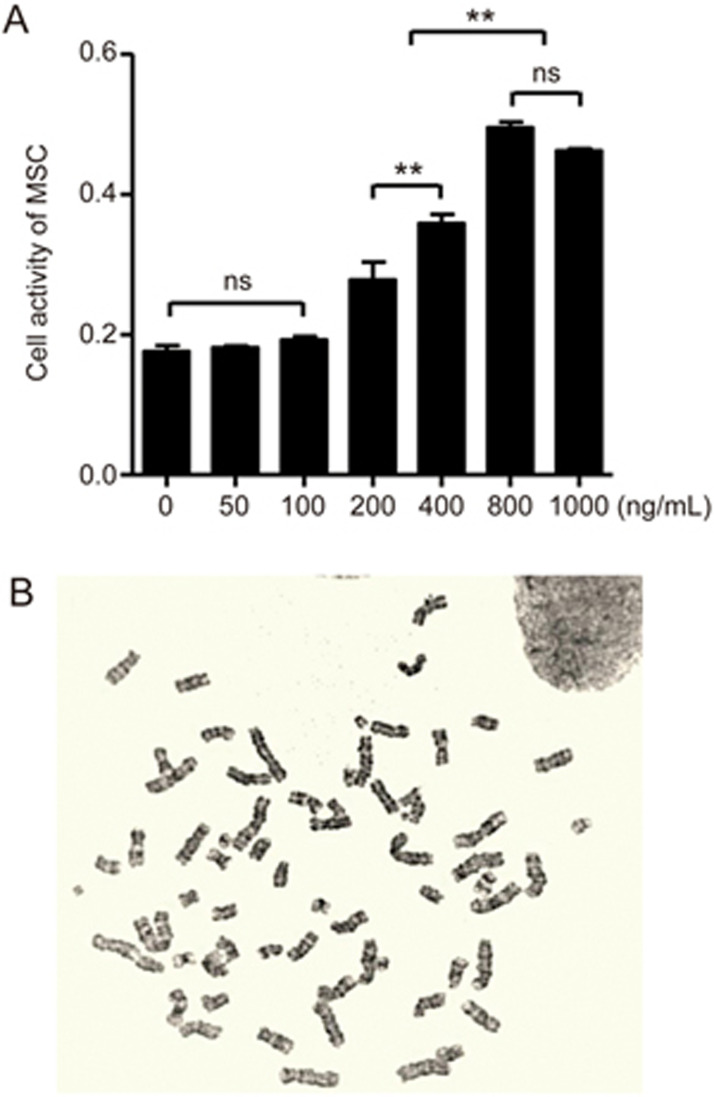

K562-MVs educate BM-MSCs to secrete TGF-β1 via transferred nucleic acid

TGF-β1 is known to be tightly associated with BM-MSC-induced progression of CML. To further evaluate the K562-MV-induced effects on BM-MSCs, we assessed the changes in TGF-β1 gene expression in BM-MSCs and TGF-β1 secretion in the supernatant. Thus, PBS, the non-MV supernatant of K562 cells (non-MV supernatant) and KG1-MVs (400 ng/mL) were used as negative controls; gene expression was detected by real-time quantitative PCR and the relative changes were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method. We found that, after 72 h of cultivation of K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL with NMSCs, the levels of TGF-β1 mRNA and protein were significantly enhanced in these K562-MSCs compared with those in other groups (Figure 4A and 4D). In keeping with the enhanced gene expression, the levels of TGF-β1 secreted by K562-MSCs, as assessed by ELISA, were also significantly higher in the group of K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL than in the controls (P<0.05, Figure 4B). However, K562-MVs at 200 ng/mL could not induce NMSCs to show these changes, indicating that this K562-MV-induced increase in TGF-β1 for BM-MSCs is MV-concentration dependent. These results indicate that K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL can promote BM-MSCs to express and secrete more TGF-β1, suggesting the increased malignant potential of these K562-MSCs.

Figure 4.

K562-MVs educate BM-MSCs to secrete TGF-β1 by nucleic acid transfer. PBS, non-MV supernatant and KG1-MVs (400 ng/mL) served as controls. NMSCs were treated with K562-MVs at 200 or 400 ng/mL for 72 h. (A) TGF-β1 mRNA was detected with real-time quantitative PCR and analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method. K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL were found to promote NMSCs to express significantly higher levels of TGF-β1 mRNA (nsP>0.05; **P<0.01, n=5), and (B) the levels of TGF-β1 secreted by K562-MV-treated NMSCs were also significantly enhanced (nsP>0.05; **P<0.01, n=5). (C) Pretreatment of K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL with RNase (1 U/mL) abolished the enhanced effect of K562-MVs on TGF-β1 mRNA expressed by the NMSCs (**P<0.01, n=4). (D) K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL were found to promote NMSCs to express significantly higher levels of TGF-β1 protein (nsP>0.05; **P<0.01, n=5). Bars, SD.

We next determined whether the enhanced TGF-β1 of K562-MSCs was associated with the packed BCR-ABL1 within K562-MVs. Thus, K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL (K562-MVs), K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL and pretreated with RNase (RNase-K562-MVs), and PBS were used to treat NMSCs, after which TGF-β1 gene expression was detected. As shown in Figure 4C, 2−ΔΔCT analysis showed that the level of the TGF-β1 gene expression in K562-MSC-treated group was 1.54±0.21 times that in the PBS-treated group. The TGF-β1 gene expression for the RNase-K562-MV-treated group was 0.70±0.24 times that in the PBS-treated group and was significantly lower than that in the K562-MV-treated group (P<0.01). These results suggest that K562-MVs enhance the TGF-β1 gene expression of BM-MSCs by the transfer of nucleic acid, most likely BCR-ABL1.

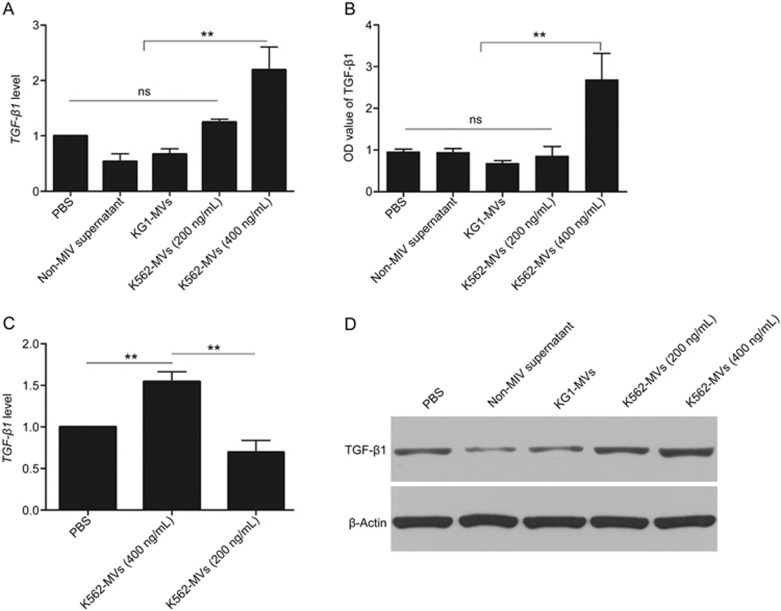

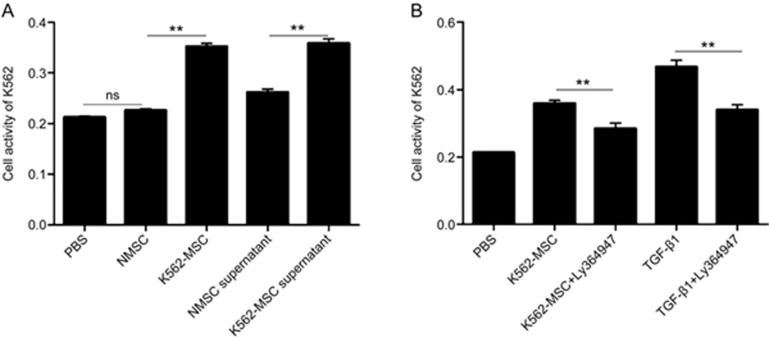

K562-MSCs promote K562 cells to proliferate partially via the enhanced secretion of TGF-β1

To further assess the transformation of K562-MSCs, we investigated the ability of these K562-MSCs to promote the proliferation of K562 cells. NMSCs, NMSC supernatant, K562-MSCs, K562-MSC supernatant, and PBS were used to treat K562 cells for 24 h. Compared with the PBS control, the NMSC supernatant, K562-MSCs and the K562-MSC supernatant all significantly increased the cell activity of K562 cells (0.26±0.01, 0.35±0.01 and 0.36±0.02 vs 0.21±0.01, respectively; P<0.05; Figure 5A), as detected by the CCK-8 kits. Additionally, the K562-MSCs and K562-MSC supernatant were both significantly different from the NMSC supernatant (P<0.05, respectively). These data indicate the efficient malignant transformation of BM-MSCs by K562-MVs.

Figure 5.

K562-MSCs promote K562 cells to proliferate partially via the enhanced secretion of TGF-β1. With PBS, NMSCs and NMSC supernatant as controls, the abilities of K562-MSCs and K562-MSC supernatant to support the proliferation of K562 cells were examined using a CCK-8 kit. (A) NMSCs showed no significant different effects with PBS on the proliferation of K562 cells (nsP>0.05, n=4), whereas K562-MSCs enhanced the proliferation of K562 cells compared with NMSCs and PBS (**P<0.01, n=4). The K562-MSC supernatant significantly promoted the proliferation of K562 cells compared with the NMSC supernatant. (B) Ly364947, a TGF-β1 inhibitor, was used to examine whether K562-MSCs induced the proliferation of K562 cells in a TGF-β1-dependent manner. PBS and TGF-β1 served as negative and positive controls, respectively, and Ly364947 could efficiently inhibit the K562-MSC-induced proliferation of K562 cells via the supernatant (**P<0.01, n=3).

Furthermore, we used Ly364947, an inhibitor of TGF-β1, to probe whether the induced cell activity of K562 cells by K562-MSCs required TGF-β1. K562-MSC supernatant, K562-MSC supernatant+Ly364947, TGF-β1, TGF-β1+Ly364947 or PBS were used to treat K562 cells for 24 h. As shown in Figure 5B, the cell activities of K562 in the K562-MSC supernatant group and TGF-β1 group were significantly increased compared with those in the PBS group (0.36±0.02 and 0.47±0.03 vs 0.21±0.01, respectively; P<0.05) but significantly decreased by Ly364947 (0.36±0.02 vs 0.28±0.27 and 0.47±0.03 vs 0.34±0.03, respectively; P<0.05). These results indicate that the TGF-β1 inhibitor can efficiently abolish the effect of K562-MSCs on the proliferation of K562 cells, indicating the key role of TGF-β1 secreted by the K562-MSCs.

Circulating MVs from CML patients contain BCR-ABL1 mRNA

As shown in Table 2, circulating MVs from all 11 CML patients who had not been treated with TKIs before sampling were confirmed to contain BCR-ABL1 mRNA, similar to K562-MVs, possibly suggesting that the hijacked BCR-ABL1 mRNA in circulating MVs in CML patients could play a potential role in the genetic cell-cell communication between leukemia cells and their environmental cells. If so, the BM-MSCs in CML patients were likely to be continuously affected by circulating MVs with BCR-ABL1.

Table 2. Detected BCR-ABL1 fusion gene in primary circulating MVs from CML patients.

| Case | Age | Sex | BCR-ABL1 (copies) | ABL1 (copies) | BCR-ABL1/ABL1 (ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32 | M | 143.5 | 195.4 | 0.734 |

| 2 | 26 | F | 37.9 | 91.2 | 0.416 |

| 3 | 14 | F | 166 | 187 | 0.888 |

| 4 | 19 | M | 77.5 | 107.1 | 0.724 |

| 5 | 32 | F | 192.4 | 282.3 | 0.682 |

| 6 | 35 | M | 160.6 | 92.7 | 1.732 |

| 7 | 42 | M | 154.3 | 88.16 | 1.75 |

| 8 | 13 | F | 102.9 | 190.78 | 0.539 |

| 9 | 45 | F | 93.4 | 90.1 | 1.037 |

| 10 | 19 | M | 188.3 | 278.5 | 0.676 |

| 11 | 40 | M | 55.34 | 37.2 | 1.488 |

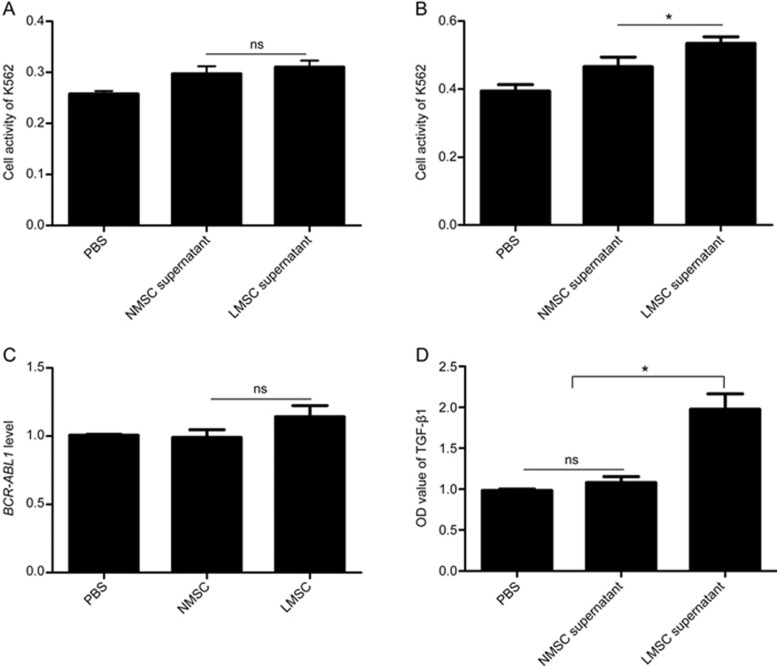

We then isolated LMSCs, which could be regarded as BM-MSCs educated by BCR-ABL1-positive MVs in vivo, and incubated K562 cells with the supernatant of LMSCs and NMSCs for 24 h and 48 h, respectively. The cell activities of K562 cells treated with the supernatant of NMSCs and LMSCs for 24 h were assessed to be 0.30±0.06 and 0.31±0.05, respectively, significantly higher than those in the PBS control (0.26±0.02; P<0.05). Meanwhile, there were no significant differences between the LMSC and NMSC supernatants (Figure 6A; P>0.05). After 48 h (Figure 6B), the same trend existed for NMSC (0.47±0.11) and LMSC (0.53±0.08) supernatants compared with that in the PBS control (0.39±0.07; P<0.05); however, the LMSC supernatant showed a significantly higher capacity to promote K562 to proliferate than NMSC supernatant (0.53±0.08 vs 0.47±0.11; P<0.05). These data imply that LMSCs, which are continuously educated by CML-MVs in vivo, can support leukemia cells. In addition, the expression of the BCR-ABL1 gene and the level of secreted TGF-β1 in MSCs, as well as the MSC supernatants (NMSCs and LMSCs), were assayed, and no differences in BCR-ABL1 expression but significant differences in secreted TGF-β1 levels were observed, as shown in Figure 6C, 6D.

Figure 6.

LMSCs support the proliferation of K562 cells more than NMSCs. The proliferation of K562 cells treated with the supernatants of NMSCs and LMSCs for 24 h (A) and 48 h (B), respectively, was assessed using the CCK-8 assay (n=3). The detected BCR-ABL1 mRNA of NMSCs and LMSCs (C) and secreted TGF-β1 protein in their supernatants (D) were compared (n=3). LMSCs and BM-MSCs from CML patients and NMSCs and BM-MSCs from patients with benign hematological disease. nsP>0.05; *P<0.05.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that BCR-ABL1-containing K562-MVs can be integrated into BM-MSCs with BCR-ABL1 mRNA by horizontal transfer. K562-MVs promote the proliferation of BM-MSCs and activate TGF-β1 signaling possibly via transferred BCR-ABL1 mRNA, which in turn triggers the proliferation of K562 cells. We further demonstrated that BCR-ABL1 mRNA is hijacked by circulating MVs in CML patients.

Improved discoveries of the interactions between leukemia cells and environmental cells are critical for a better understanding of CML pathogenesis and progression. Recently, many studies have demonstrated the key role of BM-MSCs in the TKI resistance and disease progression of CML1,2,3,6,11,12. However, the mechanisms underlying leukemia-related alterations in BM-MSCs remains poorly understood. It has been identified that G-CSF produced by leukemia cells reduces CXCL12 expression in CML BM stromal cells, and leukemia cell-related cytokine alterations contribute to leukemia-induced alterations in the CML BM microenvironment. In the present study, we demonstrate that leukemia cell-derived MVs play a part in promoting CML-induced alterations in BM-MSCs. Actually, Corrado et al22 have reported that CML exosomes, another type of EV, can also activate bone marrow stromal cells to support enhanced survival of leukemia cells, supporting the present study showing that MVs play a vital role in the crosstalk between CML cells and BM-MSCs. In addition, it has been reported that the exosomes released by K562 cells promote angiogenesis, another key leukemia-related environmental alteration20. These studies support important and new concepts regarding the contribution of CML-EVs to the transformation of BM environmental cells, which in turn provides a growth advantage for leukemia cells. Although TKI treatment corrects several abnormalities in cytokine and chemokine expression in CML cells, it may not block the secretion of EVs from CML cells that may result in the consequent activation of tumor-environmental cells, including BM-MSCs. Furthermore, it is well known that CML stem cells cannot be eliminated by TKIs and that BM-MSCs are critical key components of the niche for leukemia stem cells2. Therefore, we can reasonably infer that the activated BM-MSCs could support quiescent CML stem cells, which also release EVs to activate BM-MSCs in the niche. Thus, this vicious crosstalk could contribute to the persistence of MRD and disease progression of CML, and therapeutic strategies to block the CML-EV-mediated crosstalk would be attractive in further investigations.

The role of MSCs may act as a source of cancer stem cells in malignancies, as suggested by Houghton et al, whereby BM-MSCs are directly responsible for the development of epithelial gastric cancers triggered by chronic Helicobacter infections36,37. It is also of great interest to determine whether the BM-MSCs of CML patients are benign or malignant and with or without the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene. We and other teams25,26,31,35 have previously found that BM-MSCs from CML patients show relatively normal functions of proliferation, differentiation and hematopoietic support capabilities and are negative for BCR-ABL1, suggesting that BM-MSCs from CML patients are not malignant. By contrast, a recent study by Chandia et al38 reported that highly purified mesenchymal precursor cells (MPCs) from CML patients, without expansion in vitro, express the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene. In the present study, it can be further inferred that BM-MSCs continuously activated by CML-MVs in vivo were positive for BCR-ABL1 but were negative after being isolated from the CML tumor-microenvironment and after expansion in vitro without activation by BCR-ABL1-positive CML-MVs. The underlying mechanisms need to be further investigated in ex vivo and in vivo studies, which may benefit our understanding of the nature of CML BM-MSCs.

Numerous proteins, lipids and nucleic acids originating from parent cells have been evidenced to be carried by MVs as cargo and to be horizontally transferred between cells16,17,29,30. In the present study, similar to our recent study of K562-MVs in the transformation of hematopoietic cells, BCR-ABL1 enriched in K562-MVs also acts as the key component in the malignant education of BM-MSCs induced by K562-MVs. We observed that K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL significantly enhanced the BCR-ABL1 levels of BM-MSCs, whereas pretreatment with 1 U/mL RNase successfully abolished this effect. In addition, K562-MVs were shown to stimulate BM-MSCs to proliferate but had no effects on chromosomes, suggesting that the enhanced BCR-ABL1 levels were induced not by the Ph chromosome but by exogenous BCR-ABL1 mRNA horizontally transferred from K562-MVs. Interestingly, we found that K562-MVs at 200 mg/mL failed to the enhance expression level of BCR-ABL1 in BM-MSCs, implying that BCR-ABL1 was horizontally transferred depending on the K562-MV concentration. However, BCR-ABL1 protein was also expressed by K562-MVs (Supplementary Figure S1), and other biologically active molecules such as microRNAs should also be enriched inside K562-MVs. Thus, except for BCR-ABL1 mRNA, it is important to further investigate their expression and function in the K562-MV-mediated interactions between K562 cells and BM-MSCs.

It has been reported that MV-mediated cargo can be transferred to adjacent or remote cells to affect tumor progression and can provide a potential source of disease-related biomarkers13,18,29,30. Although a few studies concerning EVs from CML cells have emerged, none of them have studied circulating MVs from CML patients. Our study showed BCR-ABL1 mRNA to be expressed by circulating MVs of CML patients, indicating that these circulating MVs are novel and potential CML-related biomarkers. If so, we could monitor disease progression and MRD in CML patients by detecting circulating MVs. Furthermore, for CML stem cells that are believed to fuel the progression and relapse of CML, the BCR-ABL1-postive MVs released from them could be used to observe their aberrant behavior and to identify novel targets that represent important avenues for future therapeutic approaches aimed at selectively eradicating them. Thus, MV-enriched BCR-ABL1 indeed exists in CML patients, and further investigations are valuable.

Among the different downstream signaling molecules of BCR-ABL1 in CML, transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) can be released by BM-MSCs to play an essential role in the maintenance of CML stem cells and survival of leukemia cells39,40,41. In this study, we demonstrated that BCR-ABL1-positive K562-MVs at 400 ng/mL significantly increased both the mRNA and protein levels of TGF-β1 in BM-MSCs, whereas BCR-ABL1-negative KG-MVs failed. Additionally, this enhanced effect could be abolished by the destruction of the RNA content inside K562-MVs using RNase digestion. These data support the role of transferred BCR-ABL1 in the enhanced levels of TGF-β1 in K562-MSCs. We consequently investigated and found that the enhanced levels of TGF-β1 were partially responsible for the increased abilities of BM-MSCs to support the proliferation of K562 cells, using Ly364947 as a TGF-β1 inhibitor41. Herein, we provide a pathway of interaction between CML cells and BM-MSCs: CML cells release MVs enriched with BCR-ABL1 to stimulate the secretion of TGF-β1 in BM-MSCs that in turn supports the proliferation of leukemia cells. These findings are consistent with the report by Corrado et al22, although they focused on the functions of exosomes released from CML leukemia cells, another type of EV. Importantly, the packed BCR-ABL1 in MVs was shown to play a potential role in our findings on the crosstalk between CML leukemia cells and BM-MSCs.

In conclusion, based on the present and past findings, BCR-ABL1-positive K562-MVs enrich the proposed model of EV-driven CML-stroma interactions22, facilitating a favorable microenvironment for leukemic cell survival partially via TGF-β1 signaling. Our study will help to identify novel methods of MRD monitoring and worthwhile approaches for the treatment of CML.

Author contribution

Qiu-bai LI designed the study; Fen-fen FU and Xiao-jian ZHU performed the work; Hong-xiang WANG, Li-ming ZHANG, and Guo-lin YUAN collected clinical samples and patient's profile; Zhi-chao CHEN contributed to the design of the study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China to Qiu-bai LI (No 81272624 and 81071943) and to Zhi-chao CHEN (No 81170497).

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available at the website of Acta Pharmacologica Sinica.

Supplementary Information

Characteristics of K562-MVs.

References

- Zhang B, Li M, McDonald T, Holyoake TL, Moon RT, Campana D, et al. Microenvironmental protection of CML stem and progenitor cells from tyrosine kinase inhibitors through N-cadherin and Wnt–β-catenin signaling. Blood 2013; 121: 1824–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair RR, Tolentino J, Hazlehurst LA. The bone marrow microenvironment as a sanctuary for minimal residual disease in CML. Biochem Pharmacol 2010; 80: 602–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair RR, Tolentino JH, Argilagos RF, Zhang L, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Hazlehurst LA. Potentiation of Nilotinib-mediated cell death in the context of the bone marrow microenvironment requires a promiscuous JAK inhibitor in CML. Leukemia Res 2012; 36: 756–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana A, Ali G, Ali S, Khan A, Mansoor S, Malik S, et al. BCR-ABL1 in leukemia: Disguise master outplays riding shotgun. J Cancer Res Ther 2013; 9: 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Li M, McDonald T, Holyoake TL, Moon RT, Campana D, et al. Microenvironmental protection of CML stem and progenitor cells from tyrosine kinase inhibitors through N-Cadherin and Wnt-β-catenin signaling. Blood 2013; 121: 1824–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff Daniel J, Recart Angela C, Sadarangani A, Chun HJ, Barrett Christian L, Krajewska M, et al. A pan-Bcl2 inhibitor renders bone-marrow-resident human leukemia stem cells sensitive to tyrosine kinase inhibition. Cell Stem Cell 2013; 12: 316–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton-Gillespie E, Schemionek M, Klein HU, Flis S, Hoser G, Lange T, et al. Genomic instability may originate from imatinib-refractory chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells. Blood 2013; 121: 4175–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon FX, Réa D, Guilhot J, Guilhot F, Huguet F, Nicolini F, et al. Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who have maintained complete molecular remission for at least 2 years: the prospective, multicentre Stop Imatinib (STIM) trial. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 1029–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Coussens Lisa M. Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2012; 21: 309–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meads MB, Gatenby RA, Dalton WS. Environment-mediated drug resistance: a major contributor to minimal residual disease. Nat Rev Cancer 2009; 9: 665–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vianello F, Villanova F, Tisato V, Lymperi S, Ho KK, Gomes AR, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells non-selectively protect chronic myeloid leukemia cells from imatinib-induced apoptosis via the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis. Haematologica 2010; 95: 1081–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Tabe Y, Konoplev S, Xu Y, Leysath CE, Lu H, et al. CXCR4 up-regulation by imatinib induces chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) cell migration to bone marrow stroma and promotes survival of quiescent CML cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2008; 7: 48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol 2013; 200: 373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Pol E, Boing AN, Harrison P, Sturk A, Nieuwland R. Classification, functions, and clinical relevance of extracellular vesicles. Pharmacol Rev 2012; 64: 676–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camussi G, Deregibus MC, Bruno S, Grange C, Fonsato V, Tetta C. Exosome/microvesicle-mediated epigenetic reprogramming of cells. Am J Cancer Res 2011; 1: 98–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nedawi K, Meehan B, Micallef J, Lhotak V, May L, Guha A, et al. Intercellular transfer of the oncogenic receptor EGFRvIII by microvesicles derived from tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol 2008; 10: 619–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebawy M, Combes V, Lee E, Jaiswal R, Gong J, Bonhoure A, et al. Membrane microparticles mediate transfer of P-glycoprotein to drug sensitive cancer cells. Leukemia 2009; 23: 1643–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellana D, Zobairi F, Martinez MC, Panaro MA, Mitolo V, Freyssinet JM, et al. Membrane microvesicles as actors in the establishment of a favorable prostatic tumoral niche: a role for activated fibroblasts and CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axis. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 785–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh AK, Secreto CR, Knox TR, Ding W, Mukhopadhyay D, Kay NE. Circulating microvesicles in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia can stimulate marrow stromal cells: implications for disease progression. Blood 2010; 115: 1755–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineo M, Garfield SH, Taverna S, Flugy A, De Leo G, Alessandro R, et al. Exosomes released by K562 chronic myeloid leukemia cells promote angiogenesis in a src-dependent fashion. Angiogenesis 2011; 15: 33–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezu T, Ohyashiki K, Kuroda M, Ohyashiki JH. Leukemia cell to endothelial cell communication via exosomal miRNAs. Oncogene 2013; 32: 2747–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrado C, Raimondo S, Saieva L, Flugy AM, De Leo G, Alessandro R. Exosome-mediated crosstalk between chronic myelogenous leukemia cells and human bone marrow stromal cells triggers an interleukin 8-dependent survival of leukemia cells. Cancer Lett 2014; 348: 71–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loges S, Cai J, Wu G, Tan X, Han Y, Chen C, et al. Transferred BCR/ABL DNA from K562 extracellular vesicles causes chronic myeloid leukemia in immunodeficient mice. PLoS One 2014; 9: e105200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, You Y, Li Q, Zeng C, Fu F, Guo A, et al. BCR-ABL1–positive microvesicles transform normal hematopoietic transplants through genomic instability: implications for donor cell leukemia. Leukemia 2014; 28: 1666–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZG, Xu W, Sun L, Li WM, Li QB, Zou P. The characteristics and immunoregulatory functions of regulatory dendritic cells induced by mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow of patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Eur J Cancer 2012; 48: 1884–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Tang X, You Y, Li W, Liu F, Zou P. Assessment of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell biological characteristics and support hemotopoiesis function in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia Res 2006; 30: 993–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhu XJ, Zeng C, Wu PH, Wang HX, Chen ZC, et al. Microvesicles secreted from human multiple myeloma cells promote angiogenesis. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2014; 35: 230–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepanski MJ, Szajnik M, Welsh A, Whiteside TL, Boyiadzis M. Blast-derived microvesicles in sera from patients with acute myeloid leukemia suppress natural killer cell function via membrane-associated transforming growth factor- 1. Haematologica 2011; 96: 1302–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pap E. Pállinger É, Falus A. The role of membrane vesicles in tumorigenesis. Crit Rev Oncol Hema 2011; 79: 213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysoczynski M, Ratajczak MZ. Lung cancer secreted microvesicles: Underappreciated modulators of microenvironment in expanding tumors. Int J Cancer 2009; 125: 1595–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wöhrer S, Rabitsch W, Shehata M, Kondo R, Esterbauer H, Streubel B, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells in patients with chronic myelogenous leukaemia or bi-phenotypic Ph+ acute leukaemia are not related to the leukaemic clone. Anticancer Res 2007; 27: 3837–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TP, Kaeda J, Branford S, Rudzki Z, Hochhaus A, Hensley ML, et al. Frequency of major molecular responses to imatinib or interferon alfa plus cytarabine in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. New Engl J Med 2003; 349: 1423–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deregibus MC, Cantaluppi V, Calogero R, Lo Iacono M, Tetta C, Biancone L, et al. Endothelial progenitor cell–derived microvesicles activate an angiogenic program in endothelial cells by a horizontal transfer of mRNA. Blood 2007; 110: 2440–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jootar S, Pornprasertsud N, Petvises S, Rerkamnuaychoke B, Disthabanchong S, Pakakasama S, et al. Bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells from chronic myeloid leukemia t(9;22) patients are devoid of Philadelphia chromosome and support cord blood stem cell expansion. Leukemia Res 2006; 30: 1493–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrara RCV, Orellana MD, Fontes AM, Palma PVB, Kashima S, Mendes MR, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia do not express BCR-ABL and have absence of chimerism after allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Braz J Med Biol Res 2007; 40: 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton J, Stoicov C, Nomura S, Rogers AB, Carlson J, Li H, et al. Gastric cancer originating from bone marrow-derived cells. Science 2004; 306: 1568–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagg J. Mesenchymal stem cells in cancer. Stem Cell Rev 2008; 4: 119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandia M, Sayagués JM, Gutiérrez ML, Chillón ML, Aristizábal JA, Corrales A, et al. Involvement of primary mesenchymal precursors and hematopoietic bone marrow cells from chronic myeloid leukemia patients by BCR-ABL1 fusion gene. Am J Hematol 2014; 89: 288–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller GMO, Frost V, Melo JV, Chantry A. Upregulation of the TGFβ signalling pathway by Bcr-Abl: Implications for haemopoietic cell growth and chronic myeloid leukaemia. FEBS Lett 2007; 581: 1329–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka K, Hoshii T, Muraguchi T, Tadokoro Y, Ooshio T, Kondo Y, et al. TGF-β–FOXO signalling maintains leukaemia-initiating cells in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nature 2010; 463: 676–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DS, Fulzele K, Catic A, Sun CC, Dombkowski D, Hurley MP, et al. Differential regulation of myeloid leukemias by the bone marrow microenvironment. Nat Med 2013; 19: 1513–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Characteristics of K562-MVs.