Abstract

Background:

Intensive Care Unit (ICU) nurses have a vital role in the implementation of end of life (EOL) care. There is limited data on the attitude of ICU nurses toward EOL and palliation.

Aim:

This study aimed to investigate knowledge, attitude, and beliefs of intensive care nurses in eastern India toward EOL.

Materials and Methods:

A self-administered questionnaire was distributed to delegates in two regional critical care nurses' training programs.

Results:

Of 178 questionnaires distributed, 138 completed, with a response rate of 75.5*. About half (48.5*) had more than 1 year ICU experience. A majority (81.9*) agreed that nurses should be involved in and initiate (62.3*) EOL discussions. Terms “EOL care or palliative care in ICU” were new for 19.6*; 21* and 55.8* disagreed with allowing peaceful death in terminal patients and unrestricted family visits, respectively. Work experience was associated with wanting unrestricted family visitation, discontinuing monitoring and investigations at EOL, equating withholding and withdrawal of treatment, and being a part of EOL team discussions (P = 0.005, 0.01, 0.01, and 0.001), respectively. Religiousness was associated with a greater desire to initiate EOL discussions (P = 0.001).

Conclusion:

Greater emphasis on palliative care in critical care curriculum may improve awareness among critical care nurses.

Keywords: Attitude, belief, end of life, India, intensive care, knowledge, nurses, palliative care

INTRODUCTION

All disease processes are not cured with advanced medical care. Intensive Care Unit (ICU) care in many cases prolongs the process of inevitable death. Over time, palliation and end of life (EOL) care have become inexorably entwined in ICU practices and protocols. In the ICUs, nurses form a closer relationship with the patients and their relatives than the other members of the treating team.[1] Practices of EOL care vary worldwide, and the knowledge, attitude, and involvement of nurses differ.[2,3,4,5,6,7] In India, there has been a major drive from the Indian Society of Critical care Medicine and the Indian Association of Palliative Care to incorporate the requisite ideologies in medical and critical care training.[8] However, there is no information on the degree of percolation of this training into the Indian nursing curriculum and practice. This may be vital to the holistic implementation of the principles of palliation and EOL practices in ICUs. We aimed to study the knowledge and attitude of critical care nurses about EOL and palliative care in ICUs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Institutional Ethical Committee approved the study; waiver of written consent was granted. Permission was obtained to conduct the study in two separate critical care nurses' training programs. The participants were distributed the questionnaires at the end of a 20 min lecture on palliation in critical care with a request to anonymously complete the survey forms. Nurses with experience of <3 months in an ICU (in this part of the world includes mixed medical-surgical, neurosurgical, cardiac, and pediatric critical care units) were excluded from the study. Registrants common to both the trainings were excluded the second time.

The researchers did a literature survey; the VENICE tool, which has been used earlier,[5,6,7] was used as a standard guideline to enable comparability with international surveys. Two meetings among the three researchers (all critical care physicians) and one meeting with two senior critical care nurses were held to modify and build on the questions according to cultural and regional practices. In an iterative fashion, the number of questions in each domain (demographic details, personal attitude toward EOL care, involvement in EOL decisions, and beliefs about EOL practice issues) was decreased to avoid survey fatigue (English, the language of medical teaching and scientific communication, is not the first language in the population) while retaining its ability to capture essential information. A five-point Likert scale (agree strongly, agree, disagree, strongly disagree, and do not know/cannot say) was used for all domains. An explanation of four basic terminologies–withdrawal, withholding, palliation, and EOL care–was added to the introduction of the questionnaire to ensure clarity. A pilot study was carried out on ten ICU nurses to remove imperfections, wherein two questions were found to be ambiguous by the team and were reframed. The time taken to complete the questionnaire in the pilot study was <10 min.

Data analysis

The data were entered into an excel sheet and analyzed by SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Descriptive analysis for qualitative and dichotomous variables was presented as frequencies and percentages. In the data analysis, percentage means and standard deviations were employed in the calculations for the demographics. Association between independent variables was measured by Chi-square test. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographics

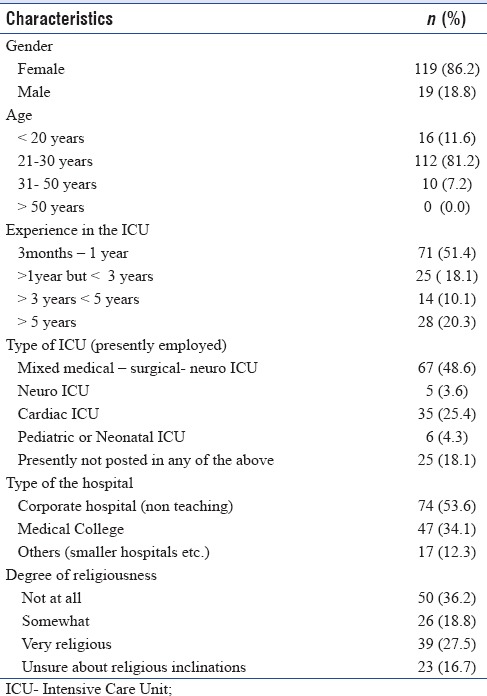

Of the 178 questionnaires distributed, 138 were returned fully filled (75.5% full response rate). Female nurses comprised 86.2% of the respondents. A majority was between 20 and 30 years of age (81.2%) with maximum respondents having 3 months to 1 year of experience in the ICU (51.4%). More nurses (48.6%) were employed in mixed medical-surgical-neuro ICUs and majority (53.6%) were from corporate centers (private hospitals not attached to teaching units) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographics of respondents (n= 138)

Knowledge and attitude

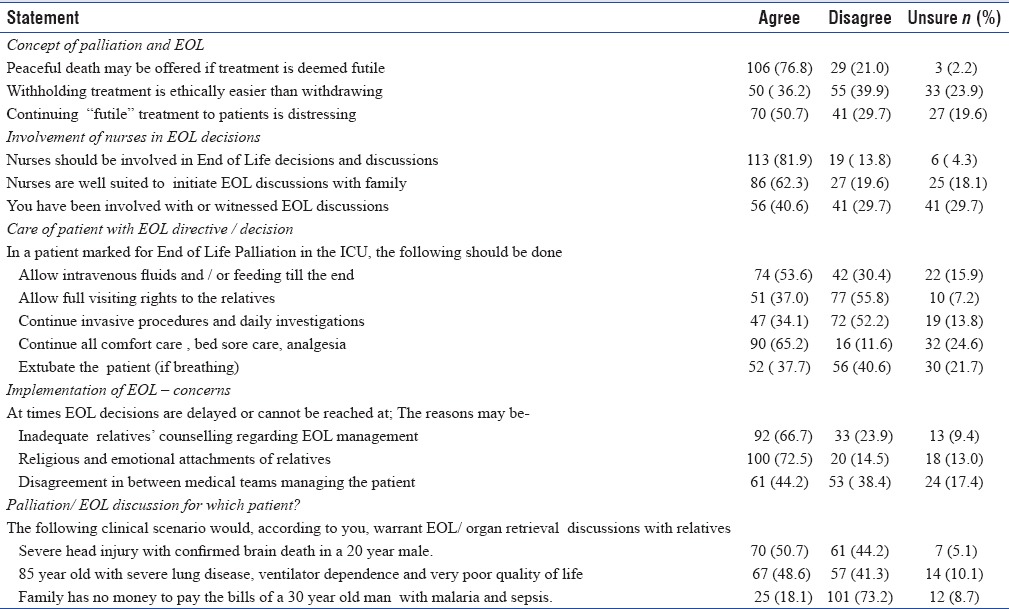

In the questions related to testing the knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes of the nurses, a majority (76.8%) agreed to offering a peaceful death in cases where further treatment is considered futile and that doing otherwise caused distress (50.7%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Nurses knowledge, beliefs and opinions regarding EOL practices in the ICU

Most nurses (81.9%) agreed that they should be involved in EOL discussions with the family: nearly 62.3% felt that they should be among the first to initiate these discussions with the family members. Almost 40.6% of respondents among those present had ever been actively involved in or witnessed this.

A greater part of respondents (53.6%) considered it correct to continue hydration and feeding till a patient under EOL directives passed away; nearly 52.2% disagreed to invasive procedures and investigations. Almost 37% believed that the relatives of these patients should have full visitation rights at the end of their patient's life.

Respondents felt that inadequate counseling, religious and emotional sentiments of relatives, and disagreement among treating teams (66%, 72.5%, and 44.2%, respectively) led to delay in EOL care discussion and implementation.

Among three clinical scenarios presented to the respondents, 50.7% agreed to start EOL/organ retrieval discussions in a young patient of traumatic brain injury and confirmed brain death; nearly 48.6% agreed for the same in an old woman with end-stage lung disease, poor quality of life, and ventilator dependence. Almost 73% disagreed to initiating EOL care discussions for financial reasons (“family runs out of money while treating a young patient with malaria”).

Two demographic factors, work experience of the nurses and religious inclination, were found to affect their knowledge and attitude toward EOL care and palliation in the ICU: the more experienced nurses considered withholding and withdrawing to be of similar significance (P = 0.01), rooted for unrestricted visits by relatives (P = 0.005), disagreed upon continuing invasive procedures and monitoring for patients with EOL care directives (P = 0.01), and had been a part of or a witness to an EOL care decision or discussion (P = 0.001).

The desire to initiate EOL care discussions with family members was significantly greater in nurses who considered themselves religious (P = 0.001).

DISCUSSION

The practice of incorporating palliation and EOL care in the ICU has gained momentum in India.[8,9,10,11,12,13] Our research throws light on the attitude, beliefs, and knowledge of EOL and palliative care among critical care nurses in eastern India. The nurses belong to a wide spectrum of ICUs with a minimum critical care experience of 3 months. Data from this part of the world are unavailable. Similar research has been done in Europe, South Africa, and Turkey, among others; interesting similarities emerge, as do pertinent differences.

The survey questions were modified from the original VIENA pattern (on which the later studies from South Africa and Turkey were based). Instead of asking the respondents' religion, we enquired about how religious they were, keeping in mind secular sensitivities. Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity are the predominant religions in the area. Questions regarding family involvement in the decision and fear of litigation were avoided as there is limited physician autonomy in taking EOL decisions, and the usual procedure followed is that of taking the consent of the family members; litigation is an issue of debate and more of a concern for the physician in these situations. Three clinical scenarios were put up to judge the intuitive assessment of the respondents about where EOL care is meaningful–two of these mirrored questions in the VIENA study–the third scenario was to assess a common situation faced in this part of the world–financial difficulties of the family precluding critical care treatment in a patient whose life is salvageable. Direct questions were asked to determine where the respondents had learned about EOL issues in ICU, if at all, as this is a relatively new concept in the country.

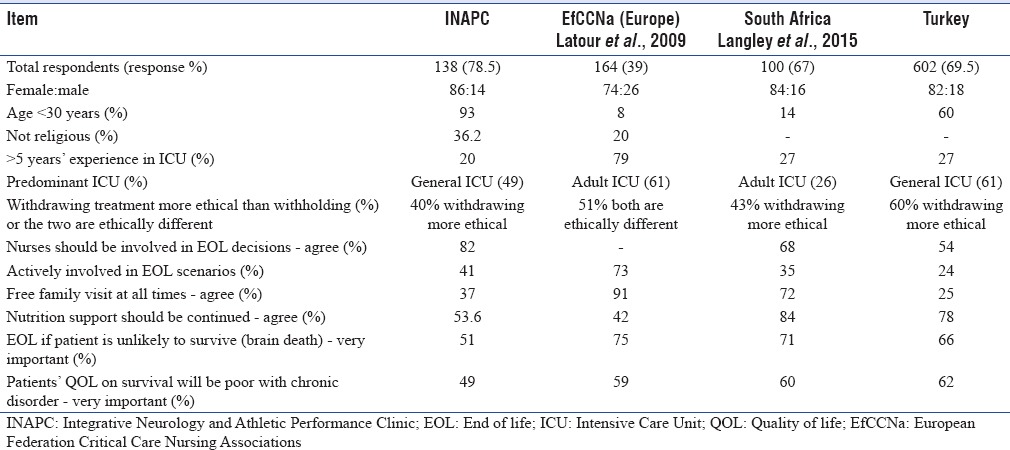

The process of withholding or withdrawing treatment at EOL, deemed similar by clinicians, is considered to be ethically different by our critical care nurses.[13,14] This dilemma has been seen uniformly in similar studies [Table 3] and has been attributed to lack of clarity surrounding ethical concepts. It is possible, however, that to the hands-on caregiver, it is more acceptable to start treatment and then withdraw if no benefit is documented than to “do nothing at all.”

Table 3.

Comparison between international studies regarding nurses knowledge and attitude

Among the case-based scenarios presented to the respondents, a larger proportion (as compared to the previous studies) disagreed on initiating EOL discussions in a young patient with brain death and in an elderly patient with poor quality of life. This could indicate poor understanding of the concepts of brain death and quality of life.

Our study had a larger number of respondents who considered themselves nonreligious [Table 3]. Religiousness, however, was associated strongly with greater desire to initiate EOL discussions when indicated.

We found certain differences between senior and junior nurses. Younger nurses in our study (as in the Turkish ICUs) were not comfortable with increased visitation rights for relatives, unlike their South African and European counterparts. This may indicate that younger/less experienced ICU nurses are nervous and unsure around relatives when dealing with EOL issues. The basic need for a human being to feel safe, with relatives available around him/her as death approaches, is well recognized, and the causes for this mindset may need to be explored further.[15,16] Experience in the ICU was also associated with greater acceptance of withdrawal as being similar to withholding. Greater experience also translated into greater involvement or witnessing of EOL discussions with families; only 40% of our nurses had been involved in (or witnessed) EOL discussions: this could indicate that there is a lack of a systematic policy of inviting nurses to be a part of the team during family meetings, senior nurses being able to join of their own desire and juniors being left behind.

A recent survey of the attitudes of Asian doctors toward withholding or withdrawal of care reveals that 70% would withhold treatment and only 20% would withdraw. The attitudes and practice varied widely across countries and regions: difference in attitude toward EOL care, patient selection, and family involvement in the ICU were also seen among doctors from low-middle-income versus high-income countries in Asia. In light of these findings, it may be pertinent to develop consensus guidelines and curriculum common for both doctors and nurses, taking into account local and regional policies.[17,18]

Our study has several strengths: it is the first such study in the Asian region. The questionnaire was developed on the basis of a tool which has been previously tested internationally; an iterative modification was applied by experts in the field. The limitations of our study include those inherent to all surveys – inability to ensure the reliability of individual responses. There was an underrepresentation of nurses with >5 years' experience in ICUs. As experience is seen to be associated with many important beliefs, our conclusions may be skewed. The results of this study, like the Asian doctors' studies, may not be generalizable to a large region. A larger pan country study will help to delineate the cultural and regional influence on nurses' perceptions to make more generalized observations.

CONCLUSION

Nurses are best placed to understand the patients' and relatives' needs and expectations. They are in a unique position to initiate EOL discussions. Our results show the strong desire of critical care nurses in this part of the world to be involved in EOL care and palliation in ICUs. Younger nurses may need further understanding of the concepts involved. The inclusion of relevant modules in nursing curriculum and regular training in the ICUs may improve the scenario.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vanderspank-Wright B, Fothergill-Bourbonnais F, Malone-Tucker S, Slivar S. Learning end-of-life care in ICU: Strategies for nurses new to ICU. Dynamics. 2011;22:22–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckstrand RL, Callister LC, Kirchhoff KT. Providing a “good death”: Critical care nurses' suggestions for improving end-of-life care. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMillen RE. End of life decisions: Nurses perceptions, feelings and experiences. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2008;24:251–9. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams JA, Bailey DE, Jr, Anderson RA, Docherty SL. Nursing roles and strategies in end-of-life decision making in acute care: A systematic review of the literature. Nurs Res Pract. 2011;52:83–4. doi: 10.1155/2011/527834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latour JM, Fulbrook P, Albarran JW. EfCCNa survey: European intensive care nurses' attitudes and beliefs towards end-of-life care. Nurs Crit Care. 2009;14:110–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2008.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langley G, Schmollgruber S, Fulbrook P, Albarran JW, Latour JM. South African critical care nurses' views on end-of-life decision-making and practices. Nurs Crit Care. 2014;19:9–17. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badir A, Topçu I, Türkmen E, Göktepe N, Miral M, Ersoy N, et al. Turkish critical care nurses' views on end-of-life decision making and practices. Nurs Crit Care. 2015 doi: 10.1111/nicc.12157. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12157. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myatra SN, Salins N, Iyer S, Macaden SC, Divatia JV, Muckaden M, et al. End-of-life care policy: An integrated care plan for the dying: A joint position statement of the Indian society of critical care medicine (ISCCM) and the Indian association of palliative care (IAPC) Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:615–35. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.140155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh M, Hwee PC. End-of-life care in the Intensive Care Unit: How Asia differs from the West. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:371–2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gursahani R, Mani RK. India: Not a country to die in. Indian J Med Ethics. 2016;1:30–5. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2016.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aslakson RA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE. The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:2418–28. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mani RK. Constitutional and legal protection for life support limitation in India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:258–61. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.164903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iyer S. Challenges in the implementation of “end-of-life care” guidelines in India: How to open the “Gordian Knot”? Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:563–4. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.140140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mani RK. Coming together to care for the dying in India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:560–2. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.140139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, Cassell J, Cox P, Hill N, et al. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:770–84. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtis JR, Vincent JL. Ethics and end-of-life care for adults in the Intensive Care Unit. Lancet. 2010;376:1347–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phua J, Joynt GM, Nishimura M, Deng Y, Myatra SN, Chan YH, et al. Withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in intensive care units in Asia. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:363–71. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phua J, Joynt GM, Nishimura M, Deng Y, Myatra SN, Chan YH, et al. Withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in low-middle-income versus high-income Asian countries and regions. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1118–27. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]