Abstract

Study Objective:

To compare the operative and reproductive outcome of hysteroscopic myomectomy using unipolar resectoscope versus bipolar resectoscope in patients with infertility and menorrhagia.

Design:

Randomized, prospective, parallel, comparative, single-blinded study.

Design Classification:

Canadian Task Force classification I.

Setting:

Tertiary care institute.

Patients:

Sixty women with submucous myoma and infertility.

Interventions:

Hysteroscopic myomectomy performed with unipolar resectoscope or bipolar resectoscope.

Measurements:

Primary outcome measures were the pregnancy-related indicators. Secondary outcome measures were the operative parameters, harmful outcomes related to the procedure, and comparison of improvement levels in the menstrual pattern after surgery between the two groups.

Main Results:

A total of 60 patients were randomized into two groups of equal size. Baseline characteristics were not significantly different between the two groups. Reduction in sodium level from pre- to postsurgery was significantly (P = 0.001) higher in the unipolar group. Nine patients (30%) in the unipolar group had hyponatremia in the postoperative period compared to none in the bipolar group (P = 0.002). However, there was no significant difference in the other operative parameters between the two groups. In both the groups, a significant improvement in the menstrual symptoms was observed after myomectomy. Pregnancy-related outcomes were similar in both the groups.

Conclusion:

The use of bipolar resectoscope for hysteroscopic myomectomy is associated with lesser risk of hyponatremia compared to unipolar resectoscope. Bipolar resectoscopic myomectomy is found to be an effective and safer alternative to unipolar resectoscopy with similar reproductive outcome.

KEYWORDS: Bipolar, myomectomy, reproductive outcome, resectoscope, unipolar

INTRODUCTION

Submucous fibroids constitute 5–10% of all uterine fibroids.[1] Submucous fibroids are associated with poor reproductive outcomes such as recurrent abortions and preterm births.[2] Infertility has also been linked to submucous myomas.[2] Significantly lower rates of pregnancy were found in patients with submucous fibroids as compared to their infertile counterparts without fibroids.[3]

Prior to the introduction of hysteroscopic resection of myomas by Neuwirth in the 1970s, the methods used to remove submucous myomas were either abdominal myomectomy, vaginal myomectomy, or hysterectomy.[4] These major gynecological procedures are associated with high morbidity.[5] In addition, these procedures may lead to the development of pelvic adhesions and subsequent reduction in fertility, thus challenging the prime indication of the procedure. With the advent of endoscopic surgery during the last two decades, transcervical hysteroscopic resection of intracavitary fibroids is now the treatment of choice for submucous fibroids.[6] Hysteroscopic myomectomy is a brief and easy to perform outpatient endoscopic daycare procedure that offers many advantages such as reduced hospital stay, decreased intraoperative and postoperative morbidity, and increased rate of vaginal delivery.[1,4]

The submucous myoma can be resected out by endoscopic resectoscope with electric loop (unipolar and bipolar) or laser, with no obvious advantage of any one technique over the other.[7] Conventionally, unipolar energy delivered through operating hysteroscopes has been used for these procedures. Excessive absorption of nonphysiological fluids such as glycine, which is used in unipolar systems as distending media, can cause hyponatremia, subsequent cerebral edema, hyperammonemia, hyponatremic encephalopathy, and rarely death. With the advent of bipolar resectoscope, hysteroscopic procedures have become much safer. Bipolar system uses normal saline as the distension medium, which reduces the risk of the harmful effects related to electrolyte imbalance and fluid overload.[8] Moreover, bipolar electrosurgery system exerts a precise tissue effect, and it has been suggested that electrical injury and intrauterine synechiae formation may be minimized with its use.[8,9,10,11]

Few studies were conducted comparing unipolar and bipolar resectoscopes for myomectomy in terms of the efficacy and the harmful outcomes related to the procedure.[12,13] One study showed bipolar resectocope to improve the fertility outcome after myomectomy.[14] However, to our knowledge, ours may be the first study to compare the two methods in terms of the effect on fertility along with the assessment of their efficacy, safety profile, and postoperative complications in infertile women with submucous myoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective, randomized, comparative, parallel, single-blinded study was conducted at our institute from July 2012 to July 2016 after obtaining approval from the Institute Review Board. A total of 484 infertile women with submucous fibroid on ultrasound were screened for the study. The inclusion criteria were the following: (1) submucous myoma of Type 0 FIGO PALM COEIN classification diagnosed during outpatient hysteroscopy, (2) history of infertility, (3) age less than 35 years, (5) written informed consent, and (6) normal semen parameters of the husband.[15] Exclusion criteria were the following: (1) patients with any other known cause of infertility were excluded from the study, (2) the presence of fibroid other than Type 0 FIGO PALM COEIN classification, (3) fibroid size more than 3 cm, or (4) more than 2 myomas.[15] At the time of initiating the study, serial numbers from 1 to 70 were randomized into two groups (1 and 2 using the Epi-Info™ version 7.0 software developed by CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA under OpenEpi random program (www.openepi.com) module) in such a way that an equal number were allocated to each group. The allocation sequence was concealed, and stapled envelopes coded as Group 1 (unipolar) and Group 2 (bipolar) were handed over to the statistician. Prospective consecutively recruited patients who were found eligible and gave written consent for participation in the study were blinded and assigned to either of the groups according to the sealed envelope allotted to them by the statistician. The appropriate procedure to be followed was decided according to the group in which they belonged.

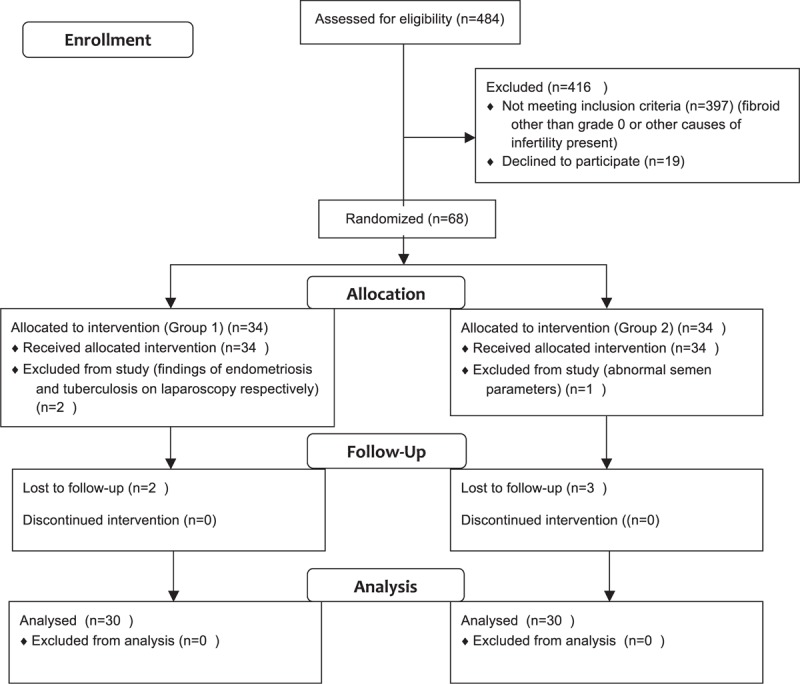

The procedure was performed in the early proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle under general anesthesia by a single operator. Because all the patients were infertile, concomitant laparoscopy was performed in all the patients to rule out any other cause of infertility other than the submucous myoma. On laparoscopy, two patients were found to have other contributing factors for infertility (endometriosis and tuberculosis), and one patient’s husband developed abnormal semen parameter on follow-up. These patients were excluded from the study. Modified intention-to-treat approach was followed, and the five patients who were lost to follow-up were excluded from the study. Thus, finally, 60 patients divided into two groups were analyzed in the study [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram depicting the outcome of women recruited in the study

All the patients received 400 µg vaginal misoprostol 6 h before the procedure for cervical ripening. Continuous flow rigid hysteroscopes were used in both the groups. In Group 1, the operation was performed using a 26-F unipolar resectoscope (Karl Storz Endoskope, Tuttlingen, Germany) with a 30° telescope equipped with a unipolar (Collin’s) knife in 1.5% glycine media. Power setting was 60 W in cutting mode. In Group 2, the operation was performed using a 26-F bipolar resectoscope (Karl Storz) equipped with a bipolar (Collin’s) knife in 0.9% saline media. The effect setting was set as five for cutting and six for coagulation in the bipolar cautery system (Autocon II 400; Karl Storz). In both the groups, the cervix was dilated to Hegar’s dilator size 10 to allow the insertion of a 26-F resectoscope. A single operator experienced in hysteroscopic myomectomy performed all the surgeries. One of the techniques described for type 0 fibroid excision is cutting the base of the fibroid and subsequent removal with forceps.[7] However, as per the surgeon’s prior experience, this technique was not followed because it can lead to difficulty in fibroid retrieval later. The fibroid floats in the fluid after its detachment and is difficult to grasp. Thus, resectoscopic excision was performed in all the patients by slicing the fibroid, starting from its top and reaching toward the base of the fibroid.

Karl Storz Hysteromat was used, and the intrauterine pressure was not allowed to exceed 150 mmHg. Fluid outflow was collected, and the fluid deficit was calculated as the difference between total used fluid volume and retrieved fluid volume. No intravenous fluids were given during the operation. The outflow portion of the hysteroscopic equipment was connected to a closed-suction unit that collects aspirated fluid inside cylindrical, transparent, rigid containers with graduated volume marks. Drained fluid from the vagina was collected into plastic calibrated drapes. Fluid deficit was monitored manually by a dedicated operating room personnel. At no point was the fluid deficit allowed to go beyond 1000 mL in the unipolar group and 1500 mL in the bipolar group. Parameters such as operation time, fluid deficit, and complications were recorded in both the groups. The operative time for the complete removal of myoma(s) was measured from the initial introduction of the dilators to the final removal of the hysteroscope. Serum sodium was measured half an hour before and after surgery in all the patients. Primary outcome measures were comparison of the groups in terms of the pregnancy outcome. Secondary outcome measures were comparison of the operative parameters, the harmful outcomes related to the procedure and the improvement of menstrual pattern after surgery between the two groups. The harmful outcomes assessed included any incident of hyponatremia, fluid overload and its complications, cervical laceration, or uterine perforation. Significant hyponatremia was defined as serum sodium level <130 mEq/L. Fluid overload was defined as deficit crossing the upper limit for the two groups respectively (as described above). Postoperatively, antibiotics in the form of oral cefixime were given for a period of 5 days to all the patients. Hormonal treatment was given to all 68 patients with estradiol valerate 4 mg daily for a period of 30 days, starting from the day after hysteroscopic myomectomy.

In all women, a second-look hysteroscopy was performed after 6 weeks of surgery to assess the normalcy of cavity with respect to adhesion formation and remnant myoma. These women were advised to resume their efforts to conceive after second-look hysteroscopy. All the patients were followed up for a minimum period of 12 months till the end of December 2016. Follow-up visits were scheduled at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 6 monthly thereafter. At each visit, menstrual pattern changes, the occurrence of pregnancy, and pregnancy outcome were noted. During follow-up, the following variables were considered as reproductive outcomes of this study − number of conceptions, number of miscarriages, number of pregnancies >30 weeks as ongoing pregnancies, number of pregnancies <30 weeks, and postoperative adhesion formation. Those women who could not visit the hospital at any particular follow-up were contacted telephonically, and required information was obtained.

Sample size

An earlier study by Makris et al.[14] showed that the pregnancy rate due to bipolar resectoscope in subfertile women with submucous myomas was 54%. Similarly, on the basis of the results of our previous study among patients who underwent hysteroscopic myomectomy by unipolar electrode loop, pregnancy rate was found to be about 71%.[16] Presuming the results obtained in these two studies will be true for this study also, we estimated that about 100 patients would be required in each group to detect a statistically significant difference with 80% power at 5% level of significance.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0 software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Normality assumptions were tested for all the continuous variables with appropriate statistical test. To test significant difference between two mean values of continuous variables that followed approximate-to-normal distribution, Student’s independent t test was used. Within-group changes in mean values from pre- to postsurgery were compared using Student’s paired t test. For non-normal data, median values were compared using Mann–Whitney U test. Frequency data across categories were compared either with chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. A two-sided confidence approach was used. For all the statistical tests, a two-tailed probability of P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

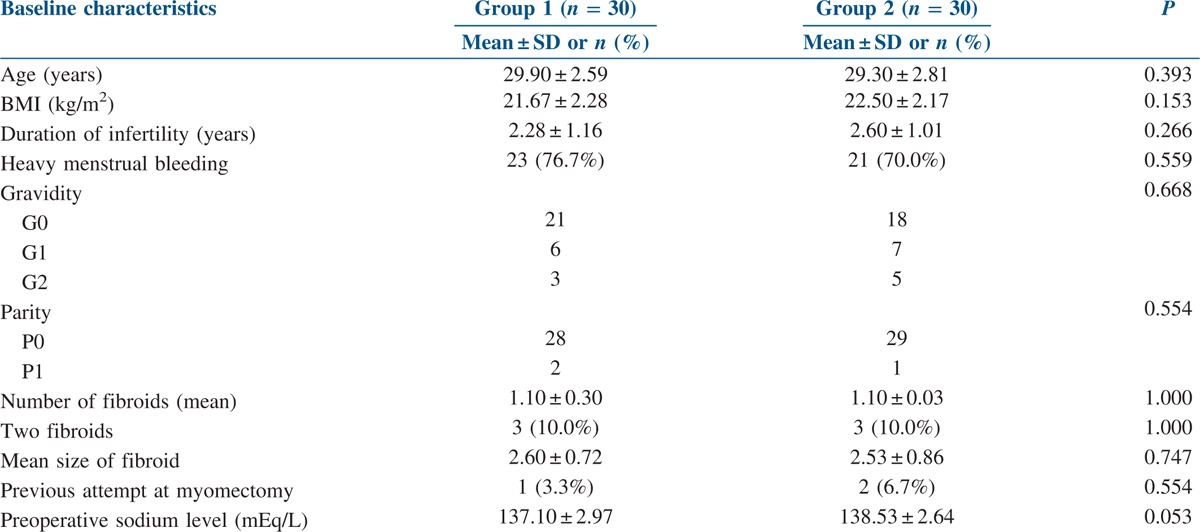

A total of 60 women with submucous fibroid and infertility were analyzed in the study. In Group 1, 21 (70%) patients had primary infertility and 9 (30%) had secondary infertility. In Group 2, primary infertility was present in 18 patients (60%) and secondary infertility in 12 patients (40%). There was no statistically significant difference in terms of presenting complaints and baseline characteristics [Table 1] between the two groups. There were three patients in each group with two fibroids, and the rest of them had a single fibroid. No case of misclassification of fibroid type was discovered during operative hysteroscopy. Diagnosis as Grade 0 fibroid was confirmed for all the patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants

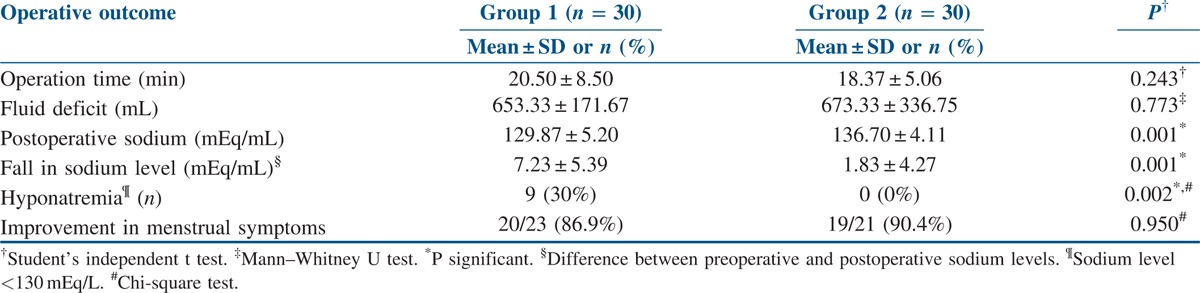

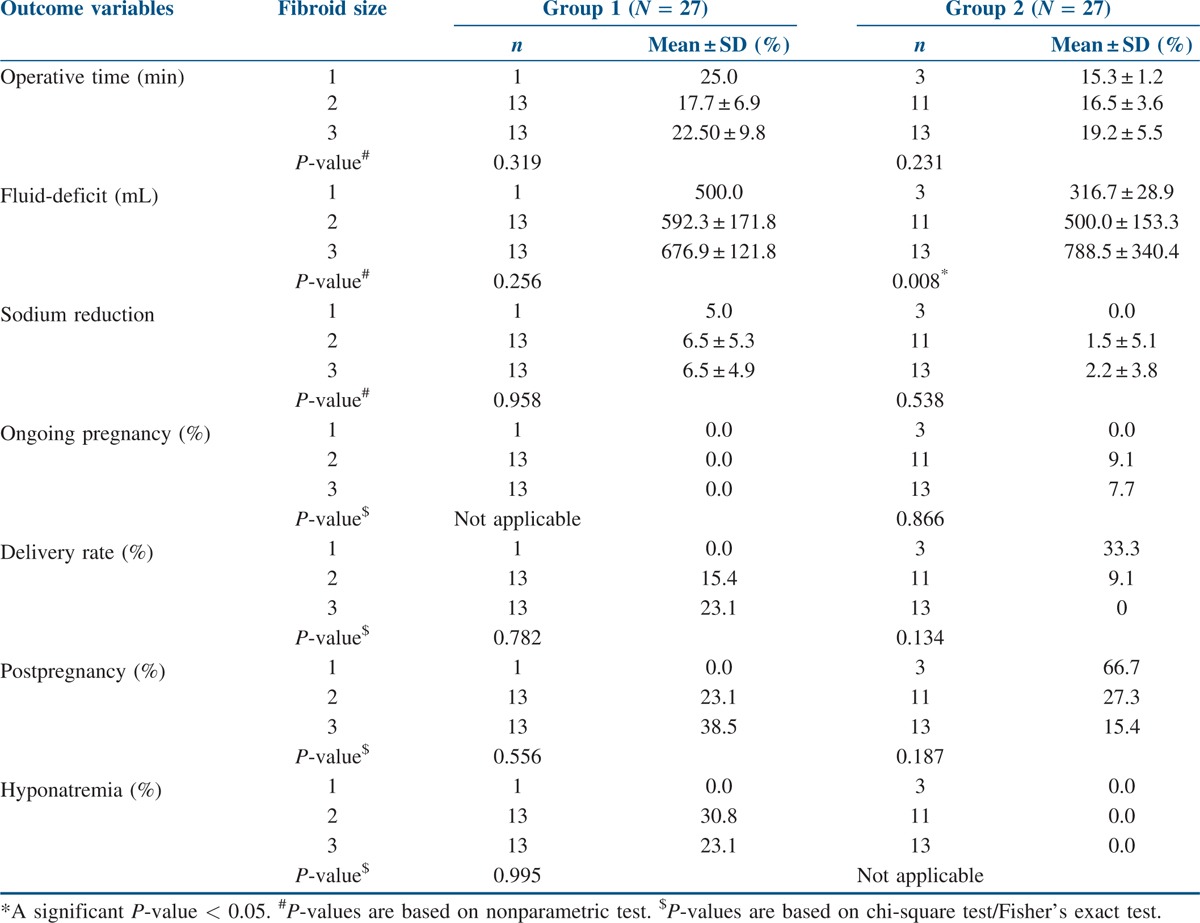

The operative parameters analyzed in the study are depicted in Table 2. While there was a significant positive correlation (r = 0.402; P = 0.028) between the amount of fluid deficit and fall in sodium level in Group 1, there was no significant correlation (r = 0.278; P = 0.138) in Group 2. There were 9 (30%) patients with hyponatremia in the group using unipolar resectoscope with 1.5% glycine as the distension medium [Table 2], and no case of hyponatremia was observed in the bipolar group. All the nine patients with hyponatremia were shifted to the intensive care unit and kept under close observation for 12–24 h. Electrolyte imbalance was corrected, and none of these patients developed pulmonary edema or other major complications of hyponatremia. All the patients were discharged in a stable condition with no long-term sequel.

Table 2.

Operative outcome and menstrual pattern changes

In our study, there was one case each of uterine perforation and cervical laceration. Difficult dilatation was encountered at the time of insertion of the hysteroscope in both these cases. The cervical tear was small and did not require any specific treatment. There was associated minor bleeding, which resolved spontaneously. The procedure was abandoned after the uterine perforation. The patient was monitored and discharged in a stable condition. Hysteroscopic myomectomy was performed successfully in a second sitting. The operative parameters were calculated as per the second sitting surgery. The patient with cervical laceration underwent myomectomy in the same sitting itself. Subsequent second-look hysteroscopy was normal for both. There was relief of menorrhagia for both patients postsurgery. However, none of them conceived during the follow-up period. Both the patients were included in the final analysis. In 12 patients, significant bleeding was observed after the procedure and was managed conservatively by intrauterine tamponade using intrauterine Foley’s catheter inflated with 15–20 cc saline (depending on the cessation of bleeding and cavity size) and kept in situ for 6 h. On second-look hysteroscopy, intrauterine adhesions were encountered in four patients of the unipolar group and two of the bipolar group (P = 0.39). Adhesiolysis was performed in all these patients in the same sitting. Remnant fibroid was observed in two patients, one in each group, which was removed during the second-look hysteroscopy simultaneously. Repeat hysteroscopy showed normal cavity in all. Two-stage resection was not required for any patient.

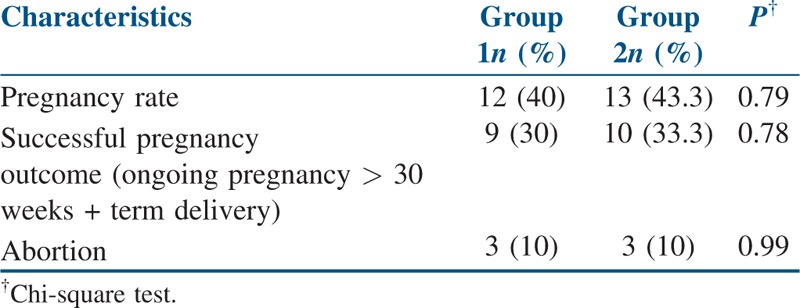

A significant improvement in menstrual symptoms was observed among 86.9% and 90.4% [Table 2] of the patients in Group 1 and Group 2, respectively. On follow-up, by the end of December 2015, 25 out of 60 patients, 12 (40%) in Group 1 and 13 (43.3%) in Group 2, had conceived. There were nine patients (30%) in Group 1 and 10 patients (33.3%) in Group 2 who had successful pregnancy outcome. Three patients in each group had first trimester abortion. There was no case of cervical incompetence in either group. The difference in pregnancy outcome between the two groups was not statistically significant [Table 3].

Table 3.

Reproductive outcome after hysteroscopic myomectomy

In both the groups, there were 27 patients with single fibroid, and among these patients, all outcome measures were tested to see if there was any association with fibroid size and outcomes. Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) values for continuous variables and percent values for frequency data by fibroid size are shown in Table 4. In Group 1, none of the outcome variables were found to be associated with fibroid size. In Group 2 also, similar results were observed except for fluid deficit outcome, which was shown to be significantly higher when the size of fibroid was more. There were only three cases with more than one fibroid and, therefore, analysis could not be performed with respect to fibroid number.

Table 4.

Comparison of outcome measures by fibroid size among the patients with single fibroid

DISCUSSION

Currently, hysteroscopic myomectomy, being a minimally invasive method, is the treatment of choice for submucous fibroids, in which patients can be managed on a daycare basis with low morbidity.[17] The electrosurgical system can be unipolar or bipolar. In the bipolar system, both electrodes are built into the thermal loop itself; hence, the current passes through the tissue interspersed between the two electrodes, thus minimizing the risk of damage to the adjacent structures. Bipolar systems such as Versapoint and bipolar resectoscope use normal saline (electrolyte medium) instead of a non-conducting medium such as glycine used with unipolar system, thus minimizing the risk of complications associated with nonelectrolyte medium. The Versapoint system has been compared to unipolar resectoscope in a number of studies and has been found to be safer in comparison to the latter.[18,19] Berg et al.[18] compared unipolar electrode with two different types of bipolar electrodes (TCRis and Versapoint). Because the loop size of Versapoint is smaller than the other two, the amount of average tissue removed was much lesser, and thus, the operative time was much longer in this Group. Another drawback of Versapoint is the increased cost. However, Versapoint does not require cervical dilation, thus avoiding cervical incompetence, cervical lacerations, and uterine perforation.[20] Technological advancements in recent years have resulted in the development of bipolar resectoscope.[8] It has the benefits of a larger loop size, better visualization, low cost, and lower risk of hyponatremia. Considering these advantages, we used bipolar resectoscope instead of the Versapoint system.

Excessive absorption of the distension medium is a less frequent but dreaded complication. Assessment of the amount of fluid absorbed in the body and timely termination of the procedure in the case of excessive fluid deficit is of utmost importance.[21] Automated fluid monitoring systems are of value here because they take into account an exact measurement of infused volume as well as all of the returned media. Such systems provide continuous measurement of the amount of media absorbed into the circulation. An alarm can be set to sound a warning when a preset volume deficit is reached. The manual monitoring system is less accurate and can lead to undetected cases of fluid overload and hyponatremia.[21] Because of unavailability of the automated system, the manual monitoring system was employed in our study.

In this study, we found nine cases of hyponatremia in the group using unipolar resectoscope with 1.5% glycine as the distension medium versus no case in the bipolar group. The significant fall in the serum sodium levels postoperatively in the unipolar group was despite no difference in the amount of mean fluid deficit and mean operative time between the two groups. A significant positive correlation was observed in the unipolar group between the amount of fluid deficit and the fall in sodium level. There was a nonsignificant relation in the bipolar group. These findings can be explained by the hypotonic nature of glycine leading to a fall in sodium concentration with increasing fluid absorption versus the isotonic nature of normal saline, which causes a lesser extent of dyselectrolytemia. Darwish et al.[13] reported a similar correlation between fluid deficit and fall in serum sodium in patients with hysteroscopic myomectomy performed using unipolar resectoscope. Litta et al. conducted a study comparing hysteroscopic myomectomy by bipolar system (60 patients) versus unipolar system (216 patients) in symptomatic women. In the bipolar group, both G1 and G2 myomas were completely removed in a single step without intraoperative/postoperative complications, whereas in the unipolar group, G2 myomas required procedure termination in 12% of the cases because of light electrolyte disturbance (22 cases) and severe hyponatremia in four cases.[12] In our previous study also, significantly lower postoperative sodium levels were observed after hysteroscopic septal resection using unipolar resectoscope in comparison to bipolar resectoscope.[22]

The risk of intrauterine synechiae is a concern after hysteroscopic myomectomy. A postprocedural evaluation of endometrial cavity for the same has been suggested by most authors after 6–8 weeks. Trans-vaginal Sonogram (TVS) preferably 3D or Hysterosalpingogram (HSG) or a second-look hysteroscopy could be performed. Hysteroscopy allows excision of the fibroid remnants during the same procedure and seems to be a more rational approach. In our study, a second-look hysteroscopy was performed to evaluate the cavity after 6 weeks. A number of modalities are in use to prevent these adhesions such as mechanical agents (intrauterine device), fluid agents (Seprafilm and Hyalobarrier), and postoperative systemic treatment (estroprogestative treatment) after operative hysteroscopy.[23,24] However, none have shown to prevent adhesions or improve the reproductive outcome.[23,24,25] Hormonal treatment with estradiol valerate in a dose of 4 mg per day for 6 weeks was administered in our study. Estrogens help by the induction of endometrial growth when used alone or in combination with progesterone.[26] Touboul et al.[27] found that the incidence of uterine synechiae after bipolar hysteroscopic resection of fibroids was 7.5%. The incidence of adhesions after unipolar system use was higher in a study by Taskin et al.[28] − 31.3% in patients with solitary fibroid and 45.5% in those with multiple fibroid. Similarly, the incidence of adhesions after hysteroscopic myomectomy was found to be lower in the bipolar group (6.7%) as compared to that in the unipolar group (13.3%) in our study. This lower incidence with bipolar system can be explained by the prevention of lateral thermal damage and stray current passage to surrounding structures, thus preventing the formation of scar tissue and adhesions. The incidence of remnant myoma was 3.3% in our study. The lower incidence could be attributed to only FIGO Type 0 fibroids being included in this study.

The American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists surveyed its members in 1993 and found a complication rate of 2% for operative hysteroscopy. The rate of major complications − perforation, hemorrhage, fluid overload, and bowel or urinary tract injury − was, however, less than 1%.[29] In our study, apart from the nine cases of hyponatremia (all in the unipolar group), there were 12 cases of bleeding immediate postoperatively managed with uterine tamponade, and one case each of uterine perforation and cervical laceration. All the complications were managed successfully on conservative treatment. If perforation is suspected or detected, especially if it is after the use of active electrode, it should be followed by laparoscopy. In addition, prompt management individualized to the case is necessary.[16] In our patient with uterine perforation, laparoscopy showed spontaneous stoppage of bleeding, not requiring cauterization and no other associated visceral injury. Second-look hysteroscopy of the patient after 6 weeks of estrogen support showed normal cavity.

Relief of menorrhagia after hysteroscopic myomectomy has been observed consistently across all studies. Fernandez et al.[30] reported a 77% success in the control of menorrhagia after surgery, 44% success in myomas of size 3 cm or more, and 94% success in myomas <3 cm. Makris et al. performed hysteroscopic myomectomy using a bipolar resectoscope in 59 women with submucous myomas and one or more infertility factors. They also found that menorrhagic incidents improved in 62.5% of the cases.[14] In this study, we included patients with fibroid size ≤3 cm to remove disparity due to difference in fibroid size. Similar to other studies, we also observed a significant improvement in menstrual symptoms after surgery in both the groups individually, though there was no statistically significant difference when comparing the two groups.

In terms of the pregnancy rate, Makris et al. reported that twenty-five women (42.4%) became pregnant after myomectomy. The pregnancy rate was notably higher when the sole reason of subfertility was the presence of myoma (54.16%), and when the size of the myoma was equal to 2.5 cm (75%) or more.[14] A large randomized-matched control study was conducted in 215 women to evaluate the results of hysteroscopic myomectomy in infertility patients.[31] The pregnancy rate in this study was 45% after hysteroscopic myomectomy, with nearly 80% conceiving within 6 months of unprotected intercourse. The pregnancy rate in the myomectomy group was almost double the control group.[31] In a recent large systematic literature review and meta-analysis of existing studies on fibroids, it was proposed that fertility outcomes decreased in women with submucosal fibroids, and removal seems to confer definite benefit.[32] In our previous study of 186 transcervical fibroid resections performed with the unipolar resectoscope in patients with infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss, at a mean follow-up of 36.5 months, we found that almost two-thirds of the infertile patients had conceived. A statistically significant reduction in pregnancy loss and a significant increase in live births was also observed in the study.[16] In this study also, there was an improved conception rate of 41.7 % after myomectomy. Among these patients, 10% had an abortion. Six patients in the unipolar group had a full-term delivery, two patients through a caesarean section, and three patients had an ongoing pregnancy. In the bipolar group, six patients had a full-term normal delivery, two underwent full-term caesarean section and two had an ongoing pregnancy >30 weeks. No case of adherent placenta was encountered. This demonstrates the clear benefit of myomectomy in symptomatic as well as asymptomatic women with submucous myoma desirous of fertility. There was no statistically significant difference in the reproductive outcome of the two groups.

Our study adds to the published literature by being the first to compare the efficacy of the unipolar and bipolar systems in improving the fertility outcome after myomectomy. The strengths of the study are that it has a prospective design, has evaluated in detail the preoperative patient characteristics and fibroid characteristics, which may affect the treatment outcome. In addition, only patients with complete follow-up were included in the study. The major limitation of the study is its small sample size. Even though the power of the study is abysmally low, on the basis of the observed outcome levels, a noninferiority trial with an adequate sample size is warranted to prove that the reproductive outcomes are similar within a clinically allowable range (say 10%) in both the methods. The study was not adequately powered to assess the affect of time on the fertility outcome, and the same was not analyzed. Larger studies are warranted to establish the efficacy and safety profile of bipolar resectoscope for hysteroscopic myomectomy, including fibroids of type 1 and 2, which were not included in this study. Another limitation of the study was the manual measurement of fluid absorption, which provides opportunity for the occurrence of undetected fluid overload.[21] This could account for the relatively high number of hyponatremia cases in our study compared with the other published studies.

CONCLUSION

Our study shows that hysteroscopic myomectomy with bipolar resectoscope is as effective as conventional unipolar resectoscope in terms of the clinical improvement of the reproductive outcome in infertile patients and in the reduction of menorrhagia. The important advantage with bipolar resectoscope is the prevention of harmful effects related to hyponatremia and its dreaded consequences, which are seen more frequently with the unipolar system. Our study suggests that bipolar resectoscope is a feasible, safer, and effective alternative to the unipolar system for hysteroscopic myomectomy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ubaldi F, Tournaye H, Camus M, Van der Pas H, Gepts E, Devroey P. Fertility after hysteroscopic myomectomy. Hum Reprod Update. 1995;1:81–90. doi: 10.1093/humupd/1.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Myomas and reproductive function. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(Suppl 1):S111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pritts EA. Fibroids and infertility: A systematic review of the evidence. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2001;56:483–91. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200108000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neuwirth RS, Amin HK. Excision of submucus fibroids with hysteroscopic control. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:95–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90471-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LaMorte AI, Lalwani S, Diamond MP. Morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:897–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agdi M, Tulandi T. Minimally invasive approach for myomectomy. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28:228–34. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1251479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Spiezio Sardo A, Mazzon I, Bramante S, Bettocchi S, Bifulco G, Guida M, et al. Hysteroscopic myomectomy: A comprehensive review of surgical techniques. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:101–19. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mencaglia L, Lugo E, Consigli S, Barbosa C. Bipolar resectoscope: The future perspective of hysteroscopic surgery. Gynecol Surg. 2009:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luciano AA. Power sources. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1995;22:423–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel A, Adshead JM. First clinical experience with new transurethral bipolar prostate electrosurgery resection system: Controlled tissue ablation (coblation technology) J Endourol. 2004;18:959–64. doi: 10.1089/end.2004.18.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stadler KR, Woloszko J, Brown IG. Repetitive plasma discharges in saline solutions. Appl Phys Lett. 2001:4503–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litta P, Leggieri C, Conte L, Dalla Toffola A, Multinu F, Angioni S. Monopolar versus bipolar device: Safety, feasibility, limits and perioperative complications in performing hysteroscopic myomectomy. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2014;41:335–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darwish AM, Hassan ZZ, Attia AM, Abdelraheem SS, Ahmed YM. Biological effects of distension media in bipolar versus monopolar resectoscopic myomectomy: A randomized trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36:810–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makris N, Vomvolaki E, Mantzaris G, Kalmantis K, Hatzipappas J, Antsaklis A. Role of a bipolar resectoscope in subfertile women with submucous myomas and menstrual disorders. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007;33:849–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, Fraser IS. FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders. FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy KK, Singla S, Baruah J, Sharma JB, Kumar S, Singh N. Reproductive outcome following hysteroscopic myomectomy in patients with infertility and recurrent abortions. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;282:553–60. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefebvre G, Vilos G, Allaire C, Jeffrey J, Arneja J, Birch C, et al. The management of uterine leiomyomas. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2003;25:396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berg A, Sandvik L, Langebrekke A, Istre O. A randomized trial comparing monopolar electrodes using glycine 1.5% with two different types of bipolar electrodes (TCRis, Versapoint) using saline, in hysteroscopic surgery. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1273–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Litta P, Spiller E, Saccardi C, Ambrosini G, Caserta D, Cosmi E. Resectoscope or Versapoint for hysteroscopic metroplasty. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;101:39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colacurci N, De Franciscis P, Mollo A, Litta P, Perino A, Cobellis L, et al. Small-diameter hysteroscopy with Versapoint versus resectoscopy with a unipolar knife for the treatment of septate uterus: A prospective randomized study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:622–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.AAGL Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide. Munro MG, Storz K, Abbott JA, Falcone T, Jacobs VR, et al. AAGL practice report: Practice guidelines for the management of hysteroscopic distending media: (Replaces Hysteroscopic Fluid Monitoring Guidelines. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2000;7:167-168) J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:137–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roy KK, Kansal Y, Subbaiah M, Kumar S, Sharma JB, Singh N. Hysteroscopic septal resection using unipolar resectoscope versus bipolar resectoscope: Prospective, randomized study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:952–6. doi: 10.1111/jog.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tonguc EA, Var T, Yilmaz N, Batioglu S. Intrauterine device or estrogen treatment after hysteroscopic uterine septum resection. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;109:226–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thubert T, Dussaux C, Demoulin G, Rivain A-L, Trichot C, Deffieux X. Influence of auto-cross-linked hyaluronic acid gel on pregnancy rate and hysteroscopic outcomes following surgical removal of intra-uterine adhesions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;193:65–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy KK, Negi N, Subbaiah M, Kumar S, Sharma JB, Singh N. Effectiveness of estrogen in the prevention of intrauterine adhesions after hysteroscopic septal resection: A prospective, randomized study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40:1085–8. doi: 10.1111/jog.12297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schenker JG, Margalioth EJ. Intrauterine adhesions: An updated appraisal. Fertil Steril. 1982;37:593–610. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)46268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Touboul C, Fernandez H, Deffieux X, Berry R, Frydman R, Gervaise A. Uterine synechiae after bipolar hysteroscopic resection of submucosal myomas in patients with infertility. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1690–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taskin O, Sadik S, Onoglu A, Gokdeniz R, Erturan E, Burak F, et al. Role of endometrial suppression on the frequency of intrauterine adhesions after resectoscopic surgery. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7:351–4. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hulka J, Peterson HB, Phillips JM, Surrey MW. Operative laparoscopy: American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists’ 1993 membership survey. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2:133–6. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)80005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernandez H, Kadoch O, Capella-Allouc S, Gervaise A, Taylor S, Frydman R. [Hysteroscopic resection of submucous myomas: Long term results] Ann Chir. 2001;126:58–64. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3944(00)00458-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shokeir T, El-Shafei M, Yousef H, Allam A-F, Sadek E. Submucous myomas and their implications in the pregnancy rates of patients with otherwise unexplained primary infertility undergoing hysteroscopic myomectomy: A randomized matched control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:724–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: An updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]