Abstract

MHC molecules evolved with the descent of jawed fishes some 350–400 million years ago. However, very little is known about the structural features of primitive MHC molecules. To gain insight into these features, we focused on the MHC class I Ctid-UAA of the evolutionarily distant grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). The Ctid-UAA H chain and β2-microglobulin (Ctid-β2m) were refolded in vitro in the presence of peptides from viruses that infect carp. The resulting peptide-Ctid-UAA (p/Ctid-UAA) structures revealed the classical MHC class I topology with structural variations. In comparison with known mammalian and chicken peptide-MHC class I (p/MHC I) complexes, p/Ctid-UAA structure revealed several distinct features. Notably, 1) although the peptide ligand conventionally occupied all six pockets (A–F) of the Ag-binding site, the binding mode of the P3 side chain to pocket D was not observed in other p/MHC I structures; 2) the AB loop between β strands of the α1 domain of p/Ctid-UAA complex comes into contact with Ctid-β2m, an interaction observed only in chicken p/BF2*2101-β2m complex; and 3) the CD loop of the α3 domain, which in mammals forms a contact with CD8, has a unique position in p/Ctid-UAA that does not superimpose with the structures of any known p/MHC I complexes, suggesting that the p/Ctid-UAA to Ctid-CD8 binding mode may be distinct. This demonstration of the structure of a bony fish MHC class I molecule provides a foundation for understanding the evolution of primitive class I molecules, how they present peptide Ags, and how they might control T cell responses.

Introduction

Immune systems are found at nearly every level in the evolutionary tree of life. However, an adaptive immune system (AIS) similar to that of mammals, with MHC molecules and Ig domain-containing TCRs and BCRs/Abs, has only been found at the level of jawed vertebrates. Because all major AIS components are found in the most primitive extant jawed fish, namely sharks, and they are absent in extant jawless fish and invertebrates, it is assumed that the AIS originated in a short time span during the origin of jawed vertebrates (1–3).

Presence of CD8+ T cells is an important feature of the AIS. With the help of immune responses involving these cells, cancerous cells and cells infected with various pathogens can be eliminated. It is impressive to realize that, presumably, CD8+ T cell–mediated immunity helps ∼20,000 species of fishes to withstand challenges from the numerous pathogens to which they are exposed in seawater and freshwater. Several genetic and functional studies suggest that although fish lack bone marrow and lymph nodes, the AIS of fish is essentially the same as that of higher jawed vertebrates including humans (4, 5). It is not clear, however, to which extent at the detailed mechanical level the immune functions in fishes and other jawed vertebrates are similar.

To date, the crystal structures of the heterotrimeric peptide–MHC class I–β2-microglobulin (β2m) protein complexes (p/MHC I) of a number of species have been determined. Nearly all of these are from humans and mice (6), with scant data from monkeys (7), cattle (8, 9), pigs (10), and chickens (11, 12). The three-dimensional structures of p/MHC I reveal that the MHC class I H chain is composed of α1, α2, and α3 domains (13). Complementary α helices and β strands in the α1 and α2 domains form the Ag-binding site (ABS). The ABS can be subdivided into pockets, and, based on the pocket organization in HLA-A2, have been named A to F (14, 15). The N- and C-termini of peptide ligands interact with key invariant MHC class I residues in the A and F pockets, which are located at the ends of the ABS. The ABSs contain amino acids that differ between alleles, and in an allelic fashion the combined six pockets restrictively bind subsets from the pool of peptides delivered by the TAP (13); the one or few peptide-binding pockets that are the most selective for peptide residues are named anchor positions. Peptide ligands have been found to be partially buried within the ABS, although some parts are exposed and can be recognized by TCRs on CD8+ T cells (16). However, hitherto this type of structural information was not available for any ectothermic (cold-blooded) vertebrate.

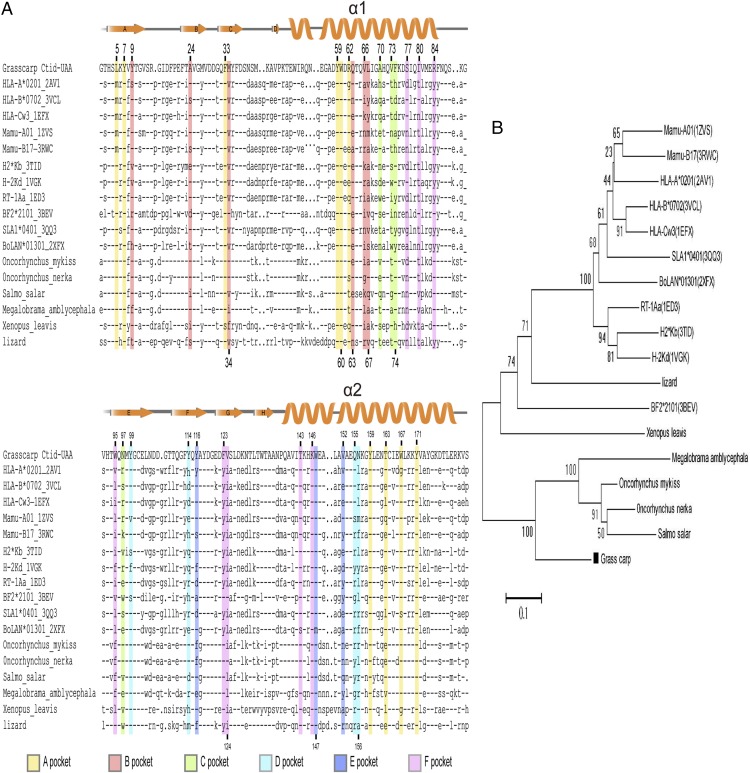

In studies of the MHC in fishes, one landmark achievement was that common carp MHC class I/II genes were cloned in 1990 by Hashimoto et al. (17). Since then, class I genes and their genomic organizations have been analyzed in sharks (18), and in zebrafish, rainbow trout, Atlantic salmon, fugu and grass carp (19). These studies revealed that the class I amino acid sequences of fish and mammals share <50% similarity and that many bony fish have MHC features distinct from those typical in mammals, like nonlinkage of class I and class II genes, extreme levels of MHC class I polymorphism, and multiple β2m loci (20). Moreover, similar to findings in humans, CD2, CD3, CD4, CD8α/β, and TCRα/β homologs have also been identified in bony fishes (21), suggesting that p/MHC I–based CD8+ T cell–mediated immunity might be present in fish species. Thus, we became interested in elucidation of the carp p/MHC I complex structure in the hope that our results will help to understand the evolution of MHC class I, how these molecules present peptide Ags, and how they might control T cell responses.

The grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) is one of the most important aquaculture species, accounting for ∼16% of global freshwater aquaculture. A draft genome sequence and transcriptomic analysis of grass carp have recently been reported (22). The genomic organization of an MHC class I gene termed Ctid-UAA (GenBank accession number AB190929), as well as two types of β2m (Ctid-β2m; GenBank accession numbers BAD22758 and BAD51478) loci and an epitope-specific immune response, were demonstrated in the grass carp in our previous studies (19, 23). The results of those studies extended our knowledge of the carp MHC class I gene by showing that it can form a p/MHC I complex which can induce CD8+ T cell immunity. In the current study, the crystal structure of carp Ctid-UAA and Ctid-β2m (BAD22758) complexed with a peptide, termed p/UAA-β2m, was determined. The results reveal that major structural features of p/MHC I complexes are identical between bony fish and birds/mammals, and also reveal that the carp p/MHC I complex structure has some unique features. The data imply that in essence the p/MHC I complex structure, and probably the matching loading and recognition systems, was already established in a common ancestor of bony fish and birds/mammals.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of proteins

The Ctid-UAA gene (AB190929) encoding the mature Ctid-UAA peptide (1–276 aa) was cloned from a plasmid that was previously constructed in our laboratory. The PCR product was ligated into the pET21a vector (Novagen; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3). When the OD500 of the bacterial culture reached 0.6 at 37°C, 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside was used to induce the expression of Ctid-UAA inclusion bodies. Six hours later, the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in cold PBS. After sonication, the sample was centrifuged at 16,000 × g, and the pellet was washed three times with a solution consisting of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 0.5% Triton X-100. Finally, the inclusion bodies were dissolved in guanidinium chloride (Gua-HCl) buffer (6 M Gua-HCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 10% v/v glycerin, and 10 mM DTT) at a concentration of 30 mg/ml (12).

The Ctid-β2m (GenBank accession no. BAD51478) inclusion bodies, which contained the 98-aa peptide, was prepared in our laboratory (23). The PCR product was ligated into the pET21a vector and transformed into E. coli strain BL21 (DE3). Ctid-β2m was expressed in inclusion bodies and purified as described above for Ctid-UAA.

Synthesis of peptides and their mutants

The SVCV-CP3 nonapeptide termed SVCV-FAN9 (SVCV-FAN9, FANFCLMMI) derived from the L protein of the spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV) and other peptides of the SVCV and grass carp hemorrhagic virus (GCHV) were selected and used in our previous experiments in accordance with the defined fundamental motif (19). All peptides were synthesized by SciLight Biotechnology (Beijing, China) (Supplemental Table I). The peptide purities were >90% as assessed using reverse-phase HPLC (SciLight Biotechnology).

Assembly of p/UAA-β2m

Preparation of the Ctid-UAA and Ctid-β2m protein complexes was conducted according to the methods that we previously reported (19). To assemble p/UAA-β2m with each viral peptide, the peptide, Ctid-UAA, and Ctid-β2m were refolded according to the gradual dilution method (19). After a 48 h incubation at 4°C, the remaining soluble portion of the complex was concentrated and purified by chromatography on a Superdex 200 16/60 column followed by Resource Q anion-exchange chromatography (GE Healthcare) as previously described (10, 12). Three of the seven peptides formed p/UAA-β2m complexes and were recovered after gel filtration; p/UAA-β2m was recovered after anion-exchange chromatography (Fig. 1).

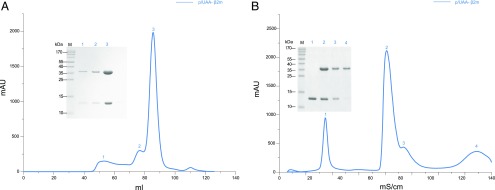

FIGURE 1.

Refolding efficiency of p/UAA-β2m. Ctid-β2m was expressed and corefolded with Ctid-UAA and SVCV-FAN9. The p/UAA-β2m curve is shown in blue. The insets show reducing SDS-PAGE gels (15%) of the peaks that are labeled on the curve. Lane M contains molecular mass markers (labeled in kDa). (A) Gel filtration chromatograms of the refolded products. (B) Anion-exchange chromatography profile of the refolded products.

Crystallization and diffraction data collection

Purified p/UAA-β2m was concentrated to 10 mg/ml in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 50 mM NaCl for crystallization. After mixing with the reservoir buffer at a 1:1 ratio, the concentrated p/UAA-β2m complex was crystallized according to the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method at 18°C. Index and Crystal Screen I and II kits (Hampton Research, Riverside, CA) were used to screen the crystals. After 7 d, p/UAA-β2m crystals were obtained with solution No. 88 from the Index kit (0.2 M ammonium citrate tribasic, pH 7.0 and 20% w/v polyethylene glycol 3350). Crystal diffraction data for p/UAA-β2m were collected at 1.9 Å resolution using beam line BL17U of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Shanghai, China). The collected intensities were indexed, integrated, corrected for absorption, scaled, and merged with HKL2000 (24, 25).

Structure determination and refinement

The p/UAA-β2m crystal structure was solved by molecular replacement via the MOLREP program using SLA-1*0401 (Protein Data Bank [PDB] code: 3QQ3) as the search model (10). Extensive model building was manually performed with COOT (25), and restrained refinement was performed with REFMAC5. Further rounds of refinement were performed with the phenix.refine program as implemented in the PHENIX software package (26), along with isotropic ADP refinement and bulk solvent modeling. The stereochemical quality of the final model was assessed using the PROCHECK program (27). The data collection and refinement statistical analysis are detailed in Table I. The isotropic B factor was calculated using the equation B = 8π2<μ2>. The analysis of the structure, including the B factor and the electronic density map, was completed using the CCP4 and PyMOL software packages.

Table I. Data collection and refinement statistics (molecular replacement).

| p/UBA-β2m | |

|---|---|

| Data processing | |

| Space group | C2 |

| Cell parameters, Å | a = 119.28, b = 50.41, c = 86.08 |

| Resolution range, Å | 50.00-1.90 |

| Total reflections | 134418 |

| Unique reflections | 31840 |

| Completeness, % | 99.0 (94.1)a |

| Rmerge, %b | 8.3 (39.7)a |

| I/σ | 17.2 (2.63)a |

| Refinement | |

| R factor, %c | 19.0 |

| Rfree, %d | 22.4 |

| Root-mean-square deviation | |

| Bonds, Å | 0.003 |

| Angles, ° | 0.765 |

| Average B factor | 28.299 |

| Most favored, % | 91.9 |

| Disallowed, % | 0.0 |

Values in parentheses represent the highest-resolution shell.

Rmerge = Σ i Σ hkl | I (hkl) − < I (hkl) > | /Σ hkl Σi Ii (hkl), where Ii (hkl) is the observed intensity, and < I (hkl) > is the average intensity from multiple measurements.

R factor = Σ(Fobs − Fcalc) / ΣFobs.

Rfree is the R factor for a subset (5%) of reflections that were selected prior to the refinement calculations but not included in the refinement.

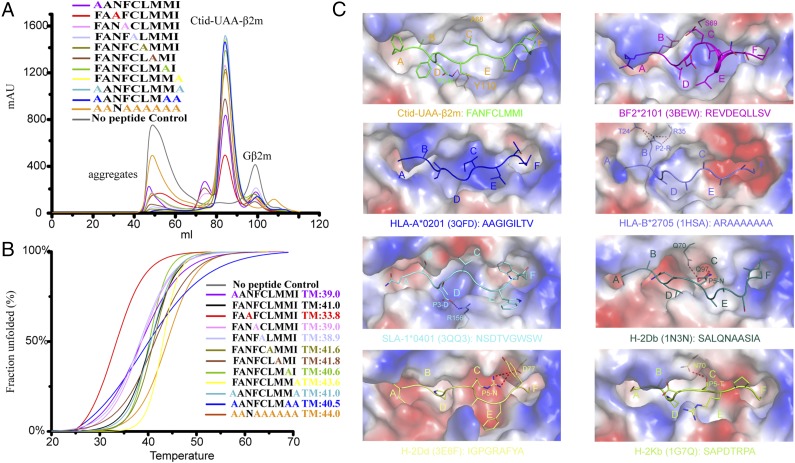

Thermostability of p/UAA-β2m

The thermostability of the p/UAA-β2m complex was tested using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. The CD spectra were specifically measured at 20°C on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter equipped with a water-circulating cell holder. The protein concentration was 150 μM in Tris buffer (20 mM Tris and 50 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). Thermal denaturation curves were determined by monitoring the CD value of the complex at 218 nm in a cell with a 1-mm optical path length while the temperature was increased from 20 to 80°C at a rate of 0.5°C/min. The temperature of the sample solution was directly measured using a thermistor. The unfolded protein fraction was calculated from the mean residue ellipticity (θ) according to the following standard method: fraction unfolded (%) = (θ − θN)/(θU − θN), where θN and θU are the mean residue ellipticity values in the fully folded and fully unfolded states, respectively. The melting temperature (Tm) was determined by fitting the data to the denaturation curves with the Origin 8.0 program (Origin Lab) as previously described (28–30).

Mutational studies of binding peptides

A sequential alanine scan of the SVCV-FAN9 peptide was performed for mutational studies. Residues at each position (except P2A) in SVCV-FAN9 were substituted with alanine, and the N- and C-terminal residues of SVCV-FAN9 were simultaneously changed to alanines. These alanine-substituted peptides were synthesized by SciLight Biotechnology and purified by HPLC to >90% purity. Each of the mutated peptides was refolded in the presence of Ctid-UAA and Ctid-β2m to assemble p/UAA-β2m. The refolded complexes were purified by gel filtration and anion-exchange chromatography as described above. The purified alanine-substituted peptide-bound complexes were then concentrated to 150 μM. Finally, the thermostabilities of these complexes were determined by CD spectroscopy as described above, and denaturation curves were generated.

Structural analysis of p/UAA-β2m

Structural illustrations and the B factor of SVCV-FAN9 were generated with PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org/). Comparison of the structure of p/UAA-β2m with the structures of other reported p/MHC I molecules was performed with the Dali online service (http://ekhidna.biocenter.helsinki.fi/dali_server/). The interface areas between β2m and MHC I H chain were calculated using the PDBePISA online service (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/prot_int/pistart.html, Supplemental Table II). The PDBePISA online service was also used to determine the accessible surface area and the buried surface area of the bound peptides. Furthermore, the interactions between the SVCV-FAN9 peptide and Ctid-UAA were assessed with CCP4 (http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/index.php). Alignments of amino acid sequences were generated by the ClustalW program supplied within DNAMAN software (Lynnon), and a phylogenetic tree was constructed based on an alignment of MHC class I ectodomain sequences using the Neighbor joining method program supplied within DNAMAN software.

Protein structure accession numbers

The p/UAA-β2m structure was deposited in the PDB, for which the entry is as follows: p/UAA-β2m: 5Y91 (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=5Y91).

Results

Primitive architecture of the carp p/MHC I structure

The assembly of the p/MHC I complex termed p/UAA and Ctid-β2m with a peptide derived from GCHV with a matching motif to form a ternary complex was described in our previous study of the carp MHC class I protein (19). In the current study, based on the primary motif, a total of seven peptides screened from the complete sequences of the SVCV and GCHV proteins, termed SVCV-CP1 through SVCV-CP7, were synthesized and used to form ternary complexes with the Ctid-UAA and Ctid-β2m molecules (Supplemental Table I). However, only two peptides, SVCV-CP2 and -CP3 (alias and hereafter SVCV-FAN9), yielded p/UAA-β2m complexes. These complexes eluted as major peaks at 85 ml elution volume on Superdex 200 gel filtration, and their identity was confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis. SVCV-FAN9 demonstrated good refolding efficiency, and the UV absorption value of the p/UAA-β2m peak reached 2000 mAU. Additionally, the p/UAA-β2m complex was able to tolerate exposure to a solution of high ionic strength during Resource Q purification (Fig. 1).

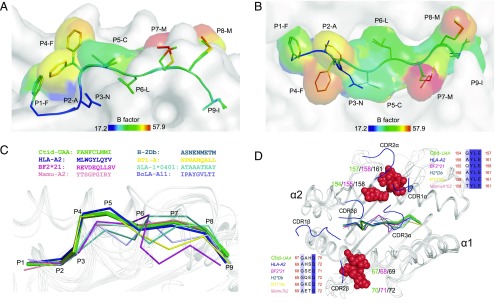

The high-purity p/UAA-β2m complex was used to screen crystals, which led to the collection of one set of p/UAA-β2m diffraction data at a resolution of 1.9 Å (Table I). The structure of p/UAA-β2m revealed that the p/UAA complex consists of Ctid-UAA, Ctid-β2m, and the SVCV-FAN9 peptide (Fig. 2A). The Ctid-UAA ABS (residues 1–180) is formed by the α1 and α2 helices atop a β-sheet bed that consists of eight antiparallel strands (residues 3–12, 21–27, 30–36, V43, 91–101, 104–114, 117–123, and 127–131). Both the α1 and α2 helices in the ABS comprise two short helices (α1 residues 47–52 and 55–83; α2 residues 134–146 and 148–176) that intersect at 45° and 90° angles, respectively (Fig. 2B). The SVCV-FAN9 peptide was accommodated by the ABS of p/UAA-β2m with the side chains of P2A, P3N, P6L, and P9I mostly buried and the side chains of P1F, P4F, P5C, P7M, and P8M at least partially presented at the ABS surface (Fig. 2B and see below).

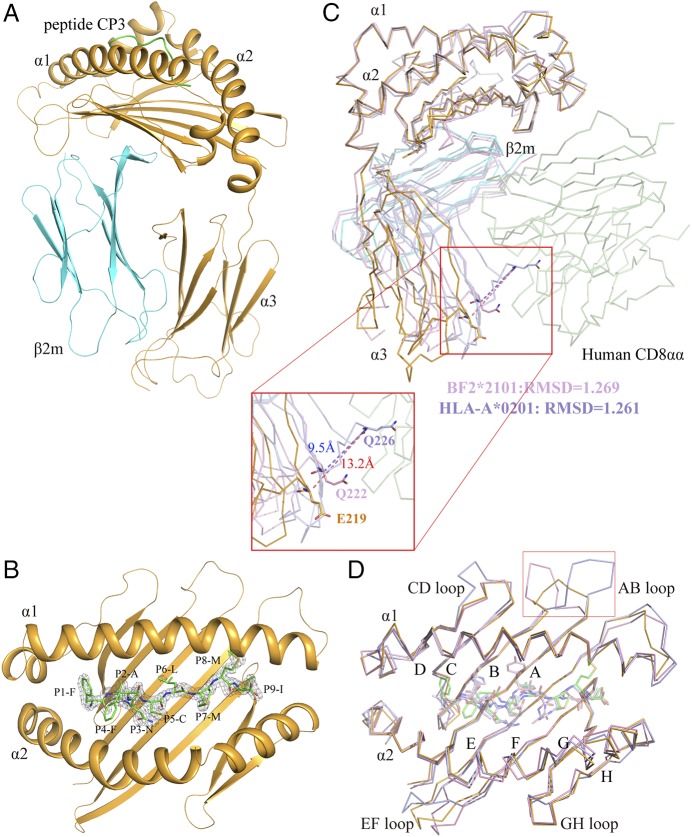

FIGURE 2.

Structural characteristics of the p/UAA-β2m complex. (A) The overall structure of the p/UAA-β2m complex. Ctid-UAA, Ctid-β2m, and the SVCV-FAN9 peptide are shown in bright orange, cyan, and green, respectively. (B) Electron density map of the SVCV-FAN9 peptide in the ABS of p/UAA-β2m. (C) The major shift in the α3 domain and the variation in the key residues for binding CD8 in p/UAA-β2m. The p/UAA-β2m structure is superposed on the HLA-A2-CD8αα (HLA-A2, light blue; CD8αα, pale green, PDB code: 1AKJ) and BF2*2101 (light pink, PDB code: 3BEW) structures. The distance between the superposed CD loops of p/UAA-β2m and the HLA-CD8αα complex is ∼13.2 Å. The residues in the CD loop that are critical for interaction with CD8 are shown in stick form, and their root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values are labeled. (D) Conservation of the overall structure of the peptide-binding domain between classical MHC class I molecules in carp p/UAA-β2m, chicken (PDB code: 3BEW), and humans (PDB code: 1AKJ). Variation is found in loops connecting the β-strands, especially in the AB loop.

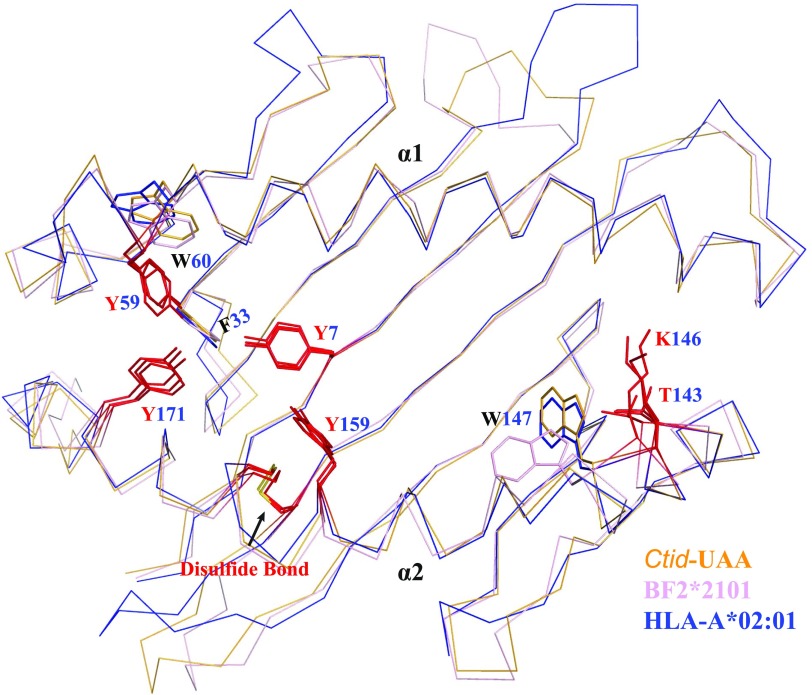

The Ctid-UAA amino acid sequence identity with known mammalian MHC class I molecules is <45%; consistent with this, the overall architecture of p/UAA has certain species-specific characteristics that may represent the primitive architecture of MHC class I. First, the main chain carbons of the α3 domain could not be well superposed between p/UAA-β2m and other known p/MHC I structures when the position of β2m was fixed. Although this phenomenon has been reported for the chicken BF2*2101, the shift of p/UAA-β2m compared with mammalian structures is much more dramatic, especially at the loop between the C and D strands (the CD loop) of the α3 domain, which plays a key role in binding to the CD8 coreceptor. At some matching positions in the α3 domain CD loops, the distance between superposed p/UAA-β2m and p/HLA-CD8 complex structures (PDB code: 1AJK) measures 13.2 Å (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, in p/UAA-β2m, the critical residue (Q) in the CD loop that in birds and mammals interacts with the CD8 CDR is substituted. This glutamine is completely conserved in higher vertebrates but is variable in fishes. The residue at this position is E in p/UAA and also E or D in many other fish MHC class I alleles (Fig. 3A). The great shift and the amino acid substitution suggest that the interaction of p/UAA and CD8 is different from that of higher vertebrates.

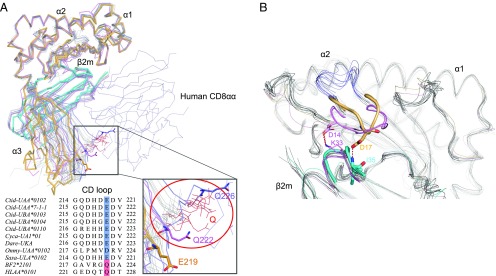

FIGURE 3.

Structural alignment of p/UAA-β2m and known p/MHC I structures from different alleles and species. p/MHC I structures were selected from different species for comparison. p/UAA-β2m, BF2*0401, and HLA-A2 are shown in orange, violet, and slate, respectively. The Ctid-β2m and BF2*2010 are shown in cyan and pink. The remaining structures are shown in gray. (A) The major shift of the α3 domain and the mutated key residue in the CD loop of p/UAA-β2m. Except for the residues in p/UAA-β2m, residues at the same position in other p/MHC I structures are shown in red. (B) Although the AB loops in the carp p/UAA-β2m and chicken BF structures can interact with β2m, in mammalian structures they cannot contact the L chain. The PDB codes of the studied p/MHC I structures are listed in Supplemental Table II.

The second major variation is the loop (AB loop) between the A and B strands in the β sheet of the α1 domain. By superposing the p/MHC I of 70 structures from different species, it was observed that the AB loop binds β2m via hydrogen bonds only in the carp and chicken p/MHC I structures, whereas the AB loop of mammalian p/MHC I does not contact β2m (Figs. 2D, 3B).

The large interface and the interactions between Ctid-UAA and β2m

The structural features of p/UAA-β2m located at the regions in contact with Ctid-β2m (the α1 AB and α3 CD loops) indicated that the interaction between Ctid-UAA and β2m in p/UAA differs from that in other known p/MHC I structures. Therefore, the size of this interface in known p/MHC I structures was analyzed using the online tool PDBePISA (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/protint/cgi-bin/piserver). The results show that p/UAA-β2m complex possesses the largest interface size, chicken BF2*2101 possesses the second largest interface size, and mammalian p/MHC I structures have a minimal interface size. The area of the interface between Ctid-UAA and Ctid-β2m is 1744 Å2, compared with chicken B4*2101 (1470 Å2) and HLA-A*0201 (1260.08 Å2). Notably, the size of the interface gradually decreases from carp (∼1700 Å2), chicken (∼1400–1600 Å2), and mammals including humans (∼1200–1400 Å2). More detailed information on this point is presented in Fig. 4A and Supplemental Table II.

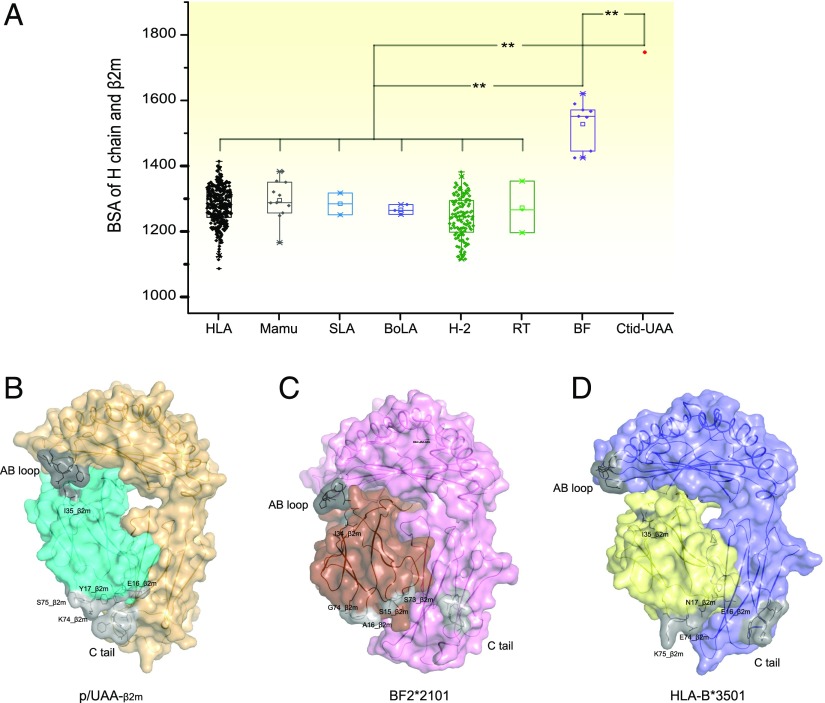

FIGURE 4.

Statistics of the interface areas of the H and L chains of p/UAA-β2m and those of known p/MHC I structures. (A) The interface areas between the H and L chains in known p/MHC I structures. A t test was used to analyze the statistical difference. Detailed information is provided in Supplemental Table II. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (B–D) The gray areas indicate the discrepant regions of the H and L chain interfaces among carp, chickens, and mammals. (B) In p/UAA-β2m, both the AB loop and the C tail of the H chain can bind to Ctid-β2m. (C) In chicken BF2*2101(BF2*2101, PDB code: 2YF5), only the AB loop can bind to β2m. (D) In mammalian p/MHC I structures (represented by HLA-B*3501, PDB code: 3LKS), neither the AB loop nor the C tail can bind to β2m.

The results of the structural comparisons showed two additional differences. The interaction of the AB loop in the α1 domain of the Ctid-UAA and the tail coil of the Ctid-β2m leads to a significant change in the interface between the H and L chains in p/UAA-β2m. In p/UAA-β2m, both the AB loop and the tail coil participate in the interaction (Fig. 4B). However, in the chicken BF2*2101 and BF2*0401 structures, only the AB loop is involved in the binding (Fig. 4C), whereas in the mammalian p/MHC I structures, neither the loop nor the tail coil is available for the interaction of the H and L chains (Fig. 4D).

Shared characteristics of ABSs reveal the common origin of p/MHC I complexes in humans and bony fishes

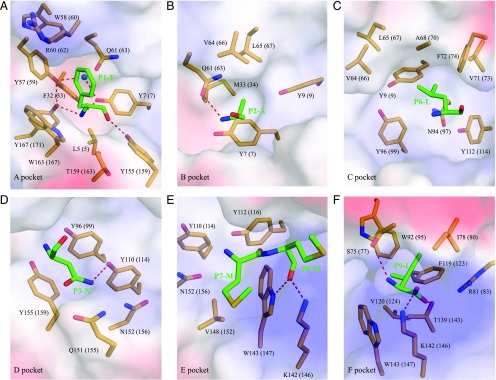

Epitope peptides are accommodated in the six pockets (A–F) of p/MHC I complexes, which were initially defined in humans. The structure of the p/UAA-β2m complex reveals that the carp MHC class I molecule already possesses an actual ABS with a volume of ∼960 Å3 and the six pocket regions A–F (Fig. 5). The interactions between the SVCV-FAN9 peptide and each pocket are listed in Table II, showing that p/UAA-β2m fixes the peptide via similar interactions as known in chicken/mammals (see also Fig. 6). Moreover, as known in p/MHC I of those other species, water molecules fill the vacant space and form hydrogen bonds that fix the peptide (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Structural analysis and comparison of the six pockets in the ABS of p/UAA-β2m. (A–F) The six pockets (A–F) of p/UAA-β2m in electronic polarity surface form (blue, positive charged; red, negative charged; white, nonpolar). The pocket residues were determined based on interaction with the peptide ligand as indicated by CCP4 software (Table II) and on our visual inspection of pocket continuity. The residues in the ABS of p/UAA-β2m are shown in stick form. Both Ctid-UAA (not in brackets) and HLA-A2 (within brackets) numberings of these residues were used for easier comparison between different studies. The SVCV-FAN9 peptide is shown in stick form, and water molecules involved in the hydrogen bond network are shown as blue balls. The hydrogen bonds and salt bridges between the peptide and pockets are shown as red dashed lines.

Table II. The interactions between the SVCV-FAN9 peptide and the peptide-binding groove of p/Ctid-UAA.

| Hydrogen Bonds and Salt Bridges | Van der Waals’ Forces | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP3 Peptide | H Chain | |||

| Residue | Atom | Residue | Atom | |

| P1-F | N | Y167 | OH | L5, Y57, R60, Q61, V64, Y78, Y155, W163, Y167 (133) |

| N | Y7 | OH | ||

| O | Y155 | OH | ||

| P2-A | N | Q61 | OE1 | Y7, Y9, Q61, V64, Y96, Y155 (62) |

| P3-N | N | Y9 | OH | Y9, V64, Y96, Y110, Q151, N152, Y155 (78) |

| ND2 | Y110 | OH | ||

| P4-F | V64, Q151, T159 (15) | |||

| P5-C | Y110, Q151, N152 (19) | |||

| P6-L | Y9, V64, A68, V71, F72 (28) | |||

| P7-M | V71, S75, W143, L146, V148 (29) | |||

| P8-M | O | K142 | NZ | V71, D74, S75, L78, K142, W143 (44) |

| O | W143 | NE1 | ||

| P9-I | N | S75 | OG | S75, I78, V79, R82, W92, F119, K142, W143(106) |

| O | T139 | OG1 | ||

| OXT | K142 | NZ(S) | ||

FIGURE 6.

Conserved residues found in the ABS of solved p/MHC I structures. HLA-A*01:01 (3BO8) and BF2*2101 (3BEW) are used to compare with p/UAA-β2m. Besides the conserved disulfide bond, nine residues were found that are conserved in the known p/MHC I structures. These residues locate in the two ends of ABS and their positions are labeled by HLA-A2 numbering. The residues which can form hydrogen bonds with the bound peptide are colored in red. There are four conserved tyrosines that form hydrogen bonds with PN main chain N and O atoms. At the other end of the ABS, the conserved T/S143 and K146 form hydrogen bonds and a salt bridge with Pomega main chain –COOH.

The A pocket is recognized as the main region that binds to the N-terminal (PN) residue of peptides; it plays an indispensable but nonrestrictive role in antigenic peptide binding. In p/UAA-β2m, there are certain strong interactions between the A pocket and SVCV-FAN9, such as the hydrogen bond network formed by Y7, Y159, and Y171 and the NH3 group in SVCV-FAN9 (for conserved MHC class I amino acid residues we follow HLA-A2 numbering, as shown within brackets in Fig. 5A). In fact, this composition of the p/UAA-β2m A pocket and the involvement of a water molecule (Fig. 5A) are exactly the same as that of other known p/MHC I structures, including for example chicken BF2*2101 (3BEW), bovine pBoLA-N01801 (2XFX), and mouse pH-2Kb (2VAB). In addition, at the sequence level, comparisons with deduced MHC class I molecules of other fishes, amphibians, and reptiles show rather good conservation of eight A pocket residues (HLA-A2 numbering: Y7, F33, Y59, W60, C101, Y159, C164, and Y171) (Fig. 7), which strongly suggests that pocket A structure has essentially been conserved in all those species.

FIGURE 7.

Amino acid sequences alignment and phylogenetic tree of MHC class I. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment of the ABS of Ctid-UAA and representative MHC class I of fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Residue positions contributing to p/UAA-β2m pockets (Fig. 5) are highlighted by pocket-specific colored shading, with preference given to the pocket contribution that we deem most important in case of participation in multiple pockets. The orange arrows above the alignment indicate the β strands, and the helices denote the α helices. Positions are labeled by HLA-A2 numbering. The symbol “-” indicates residues identical to those in p/UAA, and the symbol “.” indicates that residues are missing at that position. The PDB codes of the studied MHC class I are listed in Supplemental Table II. (B) A phylogenetic tree of MHC class I sequences in various species.

Common among known p/MHC I structures, the B, D, and F pockets harbor the side chains of the P2, P3, and C-terminal (Pomega) residues and therefore determine the specific character of the ABS. Likewise, in p/UAA-β2m, the B, D, and F pockets accommodate the side chains of P2A, P3N, and PomegaI, respectively (Fig. 5B, 5D, 5F). Residues (HLA-A2 numbering) T143 and K146 in the F pocket of p/UAA-β2m, which can form hydrogen bonds and a salt bridge with Pomega residues, are highly conserved among p/MHC I structures (Figs. 5F, 6). Besides these conserved features, the p/UAA-β2m B, D, and F pockets also have relatively unique characteristics compared with other known p/MHC I structures (Fig. 5B, 5D, 5F), as also follows from a sequence alignment (Fig. 7). The (HLA-A2 numbering) Y99 residue in the D pocket of p/UAA-β2m and its hydrogen bond with P3N (Fig. 5D) have, to our knowledge, not been described for p/MHC I before.

In known p/MHC I structures, either the C pocket or the E pocket can accommodate the side chains of the secondary anchor residues of peptides. In p/UAA-β2m, the C pocket accommodates the side chain of P6L via a hydrophobic interaction (Fig. 5C). The highly conserved (HLA-A2 numbering) K146 and W147 in the E pocket can form hydrogen bonds with the main chain of P8M (Fig. 5E).

The D pocket of p/UAA-β2m is critical for antigenic peptide binding

Generally, residues with side chains that insert deeply into the binding pocket should be considered as the anchor residues of presented peptides. In p/UAA-β2m, only P3N can form a hydrogen bond with the ABS via its side chain. The ND2 group of the P3N side chain forms a hydrogen bond with Y99 in the D pocket (Fig. 5D).

Alanine-scanning mutagenesis was performed, and the results confirmed that P3N is the primary anchor residue. Single-alanine–mutated peptides formed p/UAA complexes with variable efficiency. Only mutated P3A peptide yielded an unstable complex with the lowest refolding efficiency, and this complex was not stable during Resource Q purification. Unexpectedly, the other mutated peptides demonstrated higher efficiencies in forming p/UAA-β2m complexes (Fig. 8A). CD spectroscopy further confirmed that the complex including the SVCV-FAN9-A peptide has the lowest thermodynamic stability; its Tm is 33.8°C, more than 5°C lower than the Tm of the other complexes (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

P3N and the D pocket are critical for peptide binding in p/UAA. (A) The refolded products of Ctid-UAA and Ctid-β2m in the presence of mutated peptides tested by gel filtration chromatograms. The refolding efficiencies are represented by the relevant concentration ratios and by the heights of the p/UAA-β2m complex peak for each mutant. The mutated peptide P3A clearly yielded the lowest refolding efficiency. (B) The thermostability of p/UAA-β2m bound to the SVCV-FAN9 peptide or to one of 12 mutational peptides was tested by CD spectroscopy. The temperature was increased by 1°C/min. The unfolding curves of the fractions were determined by monitoring the CD values at 218 nm. The denaturation curves of the complexes with the different peptides are indicated in different colors. Clearly, the p/UAA-β2m complex demonstrated the least thermodynamic stability (red); its Tm was 33.8°C, more than 5°C lower than the other measurements. (C) The polarities of the ABSs of p/UAA-β2m and other p/MHC I structures indicated similar peptide-binding characteristics. Red indicates negative polarity, and blue indicates positive polarity.

The P2 and Pomega residues, which have side chains that insert deeply into the B and F pockets, are the primary anchor residues in most elucidated p/MHC I structures. However, the corefolding data, the CD spectrum, and the structure of p/UAA-β2m indicate that P3N serves as the primary anchor residue of SVCV-FAN9. The C, D, and E pockets of p/UAA-β2m merge to form a larger pocket similar to that found in chicken BF2*2101, which can promiscuously bind peptides via this large space (Fig. 8C). There are other examples of p/MHC I structures in which the sufficiency for efficient peptide binding by only one anchor residue has been demonstrated, such as P2 in the B pocket (HLA-B*2705) or P5 in the C pocket (H-2Db, H-2Dd, H-2Kb), although in those structures the P2 or Pomega residue is the small amino acid alanine (Fig. 8C). A single dominant anchor position role for the D pocket, as our data indicate for p/UAA-β2m, may be unique among investigated p/MHC I.

The conformation of the binding peptide is compatible with TCR docking

The conformation of a peptide determines its TCR recognition and binding and also affects the intensity of CD8+ T cell immunity. The total buried and exposed area of SVCV-FAN9 in p/UAA-β2m is 1403.56 Å2 (Table III). Portions of P4F, P5C, P7M, and P8M of the SVCV-FAN9 peptide extend out of the ABS and may be recognized by TCR docking. The high B factor values suggest that the great flexibility of these residues may improve T cell docking. In particular, P4F contains a large benzene ring, which suggests that it may be recognized by carp-specific TCRs due to its featured side chain (Fig. 9A, 9B). The SVCV-FAN9 peptide presents a typical “M” conformation that perfectly resembles certain HLA peptide conformations such as found in HLA-A*02:01 (3H9H), which has been shown to efficiently stimulate CD8+ T cells (Fig. 9C). According to the structures of HLA-A2 and the TCR complex, several residues located on the helices that may interact with the TCR CDR loops are present in the carp p/UAA-β2m complex (Fig. 9D).

Table III. Accessible and buried surface area calculations of the bound peptide.

| Residues | p/UAA-β2m | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Accessible Surface Area (Å2) | Buried Surface Area (Å2) | ||

| 1 | PHE | 238.38 | 218.19 |

| 2 | ALA | 81.90 | 81.90 |

| 3 | ASN | 110.10 | 108.93 |

| 4 | PHE | 176.52 | 54.34 |

| 5 | CYS | 89.41 | 28.52 |

| 6 | LEU | 152.82 | 117.64 |

| 7 | MET | 162.01 | 95.03 |

| 8 | MET | 169.31 | 105.53 |

| 9 | ILE | 223.11 | 216.37 |

| Total | 1403.56 | 1026.45 | |

FIGURE 9.

Conformation of the SVCV-FAN9 peptide and comparison with those of other peptides. (A and B) Analysis of the B factors of the SVCV-FAN9 peptide. Ctid-UAA is shown in the surface model in white; the SVCV-FAN9 peptide is colored according to the B factor. The lowest B factor, observed for P3N, indicates that the binding of this residue in the D pocket is very stable. The exposed P4, P7, and P8 residues show high B factors, and their side chains are flexible. (A) Horizontal view. (B) Vertical view. (C) The conformation of the SVCV-FAN9 peptide (thick green ribbon) was compared with that of other known peptides. The SVCV-FAN9 peptide demonstrates a typical “M” conformation. The peptide of HLA-A2 (PDB code: 1BD2) has a conformation similar to that of SVCV-FAN9, as shown by the medium blue ribbon. The remaining peptides, which are shown in different colors depending on their species, are depicted as thin ribbons. (D) Based on the HLA-A2-TCR complex structure (PDB code: 1BD2), the residues on the p/MHC I helices that are in contact with the TCR CDR loops (blue) are shown as red balls. The residues at these positions show high conservation (represented by the depth of the blue color in the sequence alignment) from carp to human.

Discussion

With grass carp p/UAA-β2m, we elucidated the first p/MHC I structure determined for any ectothermic species. Comparison of the p/MHC I structure of carp with those in chicken and mammals provides a time window for studying ancestral p/MHC I structural features at the time these species separated ∼350–400 million years ago.

Similar to previously known p/MHC I structures is the overall organization of p/UAA-β2m into a combined α1α2 domain comprising a β sheet topped by two α-helical structures, providing a groove, and two Ig-like domains α3 and β2m. Impressive is that, despite <50% sequence conservation and millions of years of independent evolution, fish class I molecules use the same mode for binding peptides as found in tetrapod species. In 1999 it was already described at the sequence level that the “key” residues Y7, Y59, T143, K146, W147, Y159, and Y171, which in mammals were known to bind peptide termini in the A, E, and F pockets, are conserved in most classical MHC class I molecules from fish to mammals (31). At the structural level the function of these key residues was later confirmed in birds (11, 12), and now our p/UAA-β2m analysis shows that the structural role of these residues is also conserved in bony fish. Other than those conserved features of the A, E, and F pockets, ABSs can differ substantially between MHC class I alleles and between species, determining which peptides are preferentially bound based on matching properties of ABS pockets and peptide side chains. The C, D, and E “pockets” of p/UAA-β2m merge to form a larger pocket similar to that found in chicken BF2*2101 (Fig. 8), and in keeping with the description of the chicken molecule (11) we use “pocket C,” “D,” and “E” nomenclature based on the matching regions in HLA-A*0201. For investigated MHC class I molecules of tetrapod species one or few pockets were found to be especially selective for the character of the bound peptide side chains (10, 12) and our alanine-substitution assay indicated that this is similar in bony fish. The selective pocket in carp p/UAA-β2m was determined to be pocket D, which was found to prefer P3N (Fig. 8). Previously, we also found a peptide-selecting role for the D pocket of the swine MHC class I molecule p/SLA-1*0401 (Fig. 8C), although, like in some other p/MHC I with established roles of pocket D in peptide selection, in p/SLA-1*0401 other pockets also have an important anchor position role (10). In contrast, our current set of data indicate that in p/UAA-β2m the only dominant anchor position may be pocket D, which together with the hydrogen bond between pocket D Y99 and P3N (Fig. 5D) forms a unique situation among analyzed structures.

The p/UAA-β2m structure allows hypotheses on the MHC class I–TCR interactions in the immunological synapse of fishes. The SVCV-FAN9 peptide shows a typical M-shaped conformation which has also been observed in pig (10), cattle (8), mouse, and human p/MHC I molecules (25, 32), and the availability of peptide side chains at the p/MHC I surface in p/UAA-β2m is similar to that found for HLA-A2 (Fig. 9). Together with the conservation of MHC class I patches that in mammals are known to interact with TCR, this shows that important structures in p/MHC I for TCR docking were already established at the level of fish (Fig. 9).

Besides the fascinating conservation of overall structure and peptide-binding mode of p/MHC I complexes between carp and higher vertebrates, the p/UAA-β2m structure also reveals unexpected differences. Major differences of p/UAA-β2m with especially mammalian p/MHC I structures are found at the interface between the H and L chains. This concerns 1) a shift in the relative position of the α3 domain (Fig. 3A) and the interaction of its C terminus with β2m which is absent in both chicken and mammalian molecules (Fig. 4B); 2) an interaction between α1 domain AB loop and β2m which is absent in mammalian p/MHC I (Fig. 3B); and 3) p/UAA-β2m having the biggest interface size (Fig. 4B). The difference in relative position of the α3 domain in p/UAA-β2m compared with that of other known p/MHC I and the fact that the major residue for CD8 binding in higher vertebrates has been substituted (Fig. 3A) suggest that the p/MHC I–CD8 binding mode in carp may be quite different from what has been found in humans and mice. Chicken p/MHC I has features intermediate to those of carp and mammalian p/MHC I, by having an intermediate H-to-L interface size (Fig. 4A), by showing interaction between the α1 domain AB loop and β2m (Fig. 3B) but not between the α3 C terminus and β2m (Fig. 4B), and by showing an intermediate relative position of the α3 domain while possessing the glutamine which in mammals is important for CD8 binding (Fig. 3A). The chicken intermediate features may be reflective of an intermediate position in an ongoing evolutionary process, but for a reliable estimation of possible evolutionary directions more structures in primitive vertebrates should be revealed.

In summary, we determined the p/MHC I structure in carp, and could conclude that the overall structure of p/MHC I and its peptide-binding mode were already established in the AIS of a common ancestor of bony fish and higher vertebrates. In future research we hope to exploit the knowledge of the carp p/MHC I structure in studies aiming to boost carp disease resistance, and to also determine more p/MHC I structures in primitive vertebrates to investigate whether they have common features which set them apart from p/MHC I in higher vertebrates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of the staff of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility of China. We thank Professor George F. Gao of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

This work was supported by the State Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 31230074), the 973 Project of the China Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant 2013CB835302), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 31572653).

The p/UAA-β2m structure presented in this article has been submitted to the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=5Y91) under accession number 5Y91.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

- ABS

- Ag-binding site

- AIS

- adaptive immune system

- CD

- circular dichroism

- GCHV

- grass carp hemorrhagic virus

- β2m

- β2-microglobulin; p/Ctid-UAA

- peptide-Ctid-UAA

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank; p/MHC I

- heterotrimeric peptide–MHC class I–β2m protein complex

- SVCV

- spring viremia of carp virus; Tm, melting temperature.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cooper M. D., Alder M. N. 2006. The evolution of adaptive immune systems. Cell 124: 815–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flajnik M. F., Kasahara M. 2010. Origin and evolution of the adaptive immune system: genetic events and selective pressures. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11: 47–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flajnik M. F., Kasahara M. 2001. Comparative genomics of the MHC: glimpses into the evolution of the adaptive immune system. Immunity 15: 351–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boehm T., Iwanami N., Hess I. 2012. Evolution of the immune system in the lower vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 13: 127–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venkatesh B., Lee A. P., Ravi V., Maurya A. K., Lian M. M., Swann J. B., Ohta Y., Flajnik M. F., Sutoh Y., Kasahara M., et al. 2014. Elephant shark genome provides unique insights into gnathostome evolution. Nature 505: 174–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero P., Corradin G., Luescher I. F., Maryanski J. L. 1991. H-2Kd-restricted antigenic peptides share a simple binding motif. J. Exp. Med. 174: 603–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu F., Lou Z., Chen Y. W., Liu Y., Gao B., Zong L., Khan A. H., Bell J. I., Rao Z., Gao G. F. 2007. First glimpse of the peptide presentation by rhesus macaque MHC class I: crystal structures of Mamu-A*01 complexed with two immunogenic SIV epitopes and insights into CTL escape. J. Immunol. 178: 944–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X., Liu J., Qi J., Gao F., Li Q., Li X., Zhang N., Xia C., Gao G. F. 2011. Two distinct conformations of a rinderpest virus epitope presented by bovine major histocompatibility complex class I N*01801: a host strategy to present featured peptides. J. Virol. 85: 6038–6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macdonald I. K., Harkiolaki M., Hunt L., Connelley T., Carroll A. V., MacHugh N. D., Graham S. P., Jones E. Y., Morrison W. I., Flower D. R., Ellis S. A. 2010. MHC class I bound to an immunodominant Theileria parva epitope demonstrates unconventional presentation to T cell receptors. PLoS Pathog. 6: e1001149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang N., Qi J., Feng S., Gao F., Liu J., Pan X., Chen R., Li Q., Chen Z., Li X., et al. 2011. Crystal structure of swine major histocompatibility complex class I SLA-1 0401 and identification of 2009 pandemic swine-origin influenza A H1N1 virus cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope peptides. J. Virol. 85: 11709–11724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koch M., Camp S., Collen T., Avila D., Salomonsen J., Wallny H. J., van Hateren A., Hunt L., Jacob J. P., Johnston F., et al. 2007. Structures of an MHC class I molecule from B21 chickens illustrate promiscuous peptide binding. Immunity 27: 885–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J., Chen Y., Qi J., Gao F., Liu Y., Liu J., Zhou X., Kaufman J., Xia C., Gao G. F. 2012. Narrow groove and restricted anchors of MHC class I molecule BF2*0401 plus peptide transporter restriction can explain disease susceptibility of B4 chickens. J. Immunol. 189: 4478–4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madden D. R. 1995. The three-dimensional structure of peptide-MHC complexes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 13: 587–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saper M. A., Bjorkman P. J., Wiley D. C. 1991. Refined structure of the human histocompatibility antigen HLA-A2 at 2.6 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 219: 277–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madden D. R., Garboczi D. N., Wiley D. C. 1993. The antigenic identity of peptide-MHC complexes: a comparison of the conformations of five viral peptides presented by HLA-A2. Cell 75: 693–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tynan F. E., Burrows S. R., Buckle A. M., Clements C. S., Borg N. A., Miles J. J., Beddoe T., Whisstock J. C., Wilce M. C., Silins S. L., et al. 2005. T cell receptor recognition of a ‘super-bulged’ major histocompatibility complex class I-bound peptide. Nat. Immunol. 6: 1114–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashimoto K., Nakanishi T., Kurosawa Y. 1990. Isolation of carp genes encoding major histocompatibility complex antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87: 6863–6867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okamura K., Ototake M., Nakanishi T., Kurosawa Y., Hashimoto K. 1997. The most primitive vertebrates with jaws possess highly polymorphic MHC class I genes comparable to those of humans. Immunity 7: 777–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen W., Jia Z., Zhang T., Zhang N., Lin C., Gao F., Wang L., Li X., Jiang Y., Li X., et al. 2010. MHC class I presentation and regulation by IFN in bony fish determined by molecular analysis of the class I locus in grass carp. J. Immunol. 185: 2209–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magor K. E., Shum B. P., Parham P. 2004. The beta 2-microglobulin locus of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) contains three polymorphic genes. J. Immunol. 172: 3635–3643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakanishi T., Shibasaki Y., Matsuura Y. 2015. T cells in fish. Biology 4: 640–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y., Lu Y., Zhang Y., Ning Z., Li Y., Zhao Q., Lu H., Huang R., Xia X., Feng Q., et al. 2015. The draft genome of the grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) provides insights into its evolution and vegetarian adaptation. Nat. Genet. 47: 625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen W., Gao F., Chu F., Zhang J., Gao G. F., Xia C. 2010. Crystal structure of a bony fish beta2-microglobulin: insights into the evolutionary origin of immunoglobulin superfamily constant molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 22505–22512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276: 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borbulevych O. Y., Piepenbrink K. H., Gloor B. E., Scott D. R., Sommese R. F., Cole D. K., Sewell A. K., Baker B. M. 2009. T cell receptor cross-reactivity directed by antigen-dependent tuning of peptide-MHC molecular flexibility. Immunity 31: 885–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Terwilliger T. C. 2002. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58: 1948–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laskowski R. A., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. 1993. Main-chain bond lengths and bond angles in protein structures. J. Mol. Biol. 231: 1049–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tobita T., Oda M., Morii H., Kuroda M., Yoshino A., Azuma T., Kozono H. 2003. A role for the P1 anchor residue in the thermal stability of MHC class II molecule I-Ab. Immunol. Lett. 85: 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hein Z., Uchtenhagen H., Abualrous E. T., Saini S. K., Janßen L., Van Hateren A., Wiek C., Hanenberg H., Momburg F., Achour A., et al. 2014. Peptide-independent stabilization of MHC class I molecules breaches cellular quality control. J. Cell Sci. 127: 2885–2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saini S. K., Ostermeir K., Ramnarayan V. R., Schuster H., Zacharias M., Springer S. 2013. Dipeptides promote folding and peptide binding of MHC class I molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 15383–15388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hashimoto K., Okamura K., Yamaguchi H., Ototake M., Nakanishi T., Kurosawa Y. 1999. Conservation and diversification of MHC class I and its related molecules in vertebrates. Immunol. Rev. 167: 81–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith K. J., Reid S. W., Stuart D. I., McMichael A. J., Jones E. Y., Bell J. I. 1996. An altered position of the alpha 2 helix of MHC class I is revealed by the crystal structure of HLA-B*3501. Immunity 4: 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.