Abstract

Background: Power wheelchairs capable of overcoming environmental barriers, such as uneven terrain, curbs, or stairs, have been under development for more than a decade. Method: We conducted a systematic review of the scientific and engineering literature to identify these devices, and we provide brief descriptions of the mechanism and method of operation for each. We also present data comparing their capabilities in terms of step climbing and standard wheelchair functions. Results: We found that all the devices presented allow for traversal of obstacles that cannot be accomplished with traditional power wheelchairs, but the slow speeds and small wheel diameters of some designs make them only moderately effective in the basic area of efficient transport over level ground and the size and configuration of some others limit maneuverability in tight spaces. Conclusion: We propose that safety and performance test methods more comprehensive than the International Organization for Standards (ISO) testing protocols be developed for measuring the capabilities of advanced wheelchairs with step-climbing and other environment-negotiating features to allow comparison of their clinical effectiveness.

Keywords: assistive technology, literature review, power wheelchairs, robotics, wheelchairs

Based on 2010 census data, there are an estimated 3.6 million wheelchair users over the age of 15 in the United States.1 Of those, 2.0 million are over the age of 65. The same data have been used to estimate that 15.2 million (39.4%) of individuals over the age of 65 experience difficulty in ambulation and 11.2 million of those (29.0% of individuals over 65 years old) experience severe difficulty. These demographics in the United States are not unique. Another report found that “20% of Danish men aged 67–79 years and 39% of those over 79 years of age are not able to walk 400 meters without difficulty.”2(p72) Older Danish women fared slightly worse, with 25% and 58% of the respective age groups experiencing difficulty walking 400 m.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1% of the worldwide population requires a wheelchair.3 As the number of older adults increases, particularly in the United States, Western Europe, China, and Japan, there will be more and more people with ambulatory difficulties, and such individuals could be expected to use assistive devices such as walkers and wheelchairs.1

Among wheelchair users, approximately 15% use electric-powered wheelchairs (EPWs).4 EPWs provide community integration, independence, and increased quality of life for persons with disabilities.5 Still, powered wheelchair users face challenges when going outdoors, including slopes, steps, uneven surfaces, and other environmental barriers.2,6 It is not unusual for EPW users to adapt their behavior in order to avoid such obstacles,2,7 but such compromises may prevent individuals from visiting the places they might otherwise choose to frequent.

In addition to limiting independence, environmental barriers can lead to injuries for wheelchair users. In 2003, there were over 100,000 emergency room visits resulting from wheelchair-related injuries, of which more than 65% could be attributed to tips and falls.8 A survey of 109 wheelchair users who had experienced incidents found that 42% of the incidents could be characterized as a tip or fall and hospitalizations resulting from incidents were weighted toward those categories.9 The same study further reported that 79% of the tips and falls occurred on nonlevel surfaces or rough ground. These findings were congruent with an earlier analysis of adverse events related to wheelchairs that found inclines, changes in surface, and curbs account for the majority of environmentally caused events.10 A more recent survey of 95 wheelchair users reported that 55% of the participants had at least one incident in the past 3 years and 88% of those incidents could be categorized as tips or falls.11 A study of 702 veterans who used wheelchairs conducted over a 12-month period found that 31% experienced a fall and 14% experienced a fall that resulted in an injury.12

For EPWs to provide greater independence, ease of use, and increased safety, it is desirable for them to incorporate features to detect, compensate for, and overcome environmental barriers. Obstacle-climbing wheelchairs are under development at a number of research institutions, but few have been available on the market. In 2014, noting the paucity of approvals for such devices, the US Food and Drug Administration reclassified stair-climbing wheelchairs from class 3 (requiring premarket authorization) to class 2 (special controls).13 Although lack of insurance coverage, at least in the United States, remains an issue, this decision lowers one significant barrier to new stair-climbing wheelchair designs entering the market, and thereby has the potential for intensifying research on the topic.

In 2005, Ding and Cooper published an overview of advanced power wheelchair devices, including some wheelchairs capable of stair climbing,6 but no comprehensive summary of research in the topic has been published since. The goal of this article is to provide researchers an overview of the mechanisms currently being used in obstacle-climbing wheelchair prototypes and to provide some comparison of their capabilities.

Methods

To gather information on powered wheelchairs and functionally similar personal mobility devices, as well as designs that are capable of climbing curbs or at least one step, we searched the IEEE Digital Library and PubMed combining the key words “wheelchair” with “climb,” “stair,” “step,” “curb,” “obstacle,” and “robotic.” Additional articles were found by individually searching, for example, by checking references in articles found through the digital database searches. The search was restricted to articles in English. To focus the present review on devices in active development, we only considered results from 2005 onward. For a described device to be included in the review, it must have been intended for use as a mobility aid for older adults or people with disabilities and be at least at the stage of a physical prototype. Devices must be fully driven (ie, not a piece added onto a manual wheelchair), be self-contained, and allow the user to negotiate the intended obstacles independently. A typical EPW can surmount obstacles from 5 cm to 7.5 cm (2 in. to 3 in.). As the ability of a wheelchair to overcome obstacles can be increased simply by increasing the wheel radius, only devices including other mechanisms are presented. An attempt was made to contact the primary author on each article to obtain the most up-to-date information on the physical dimensions of each device and the current capabilities of each prototype.

Device descriptions

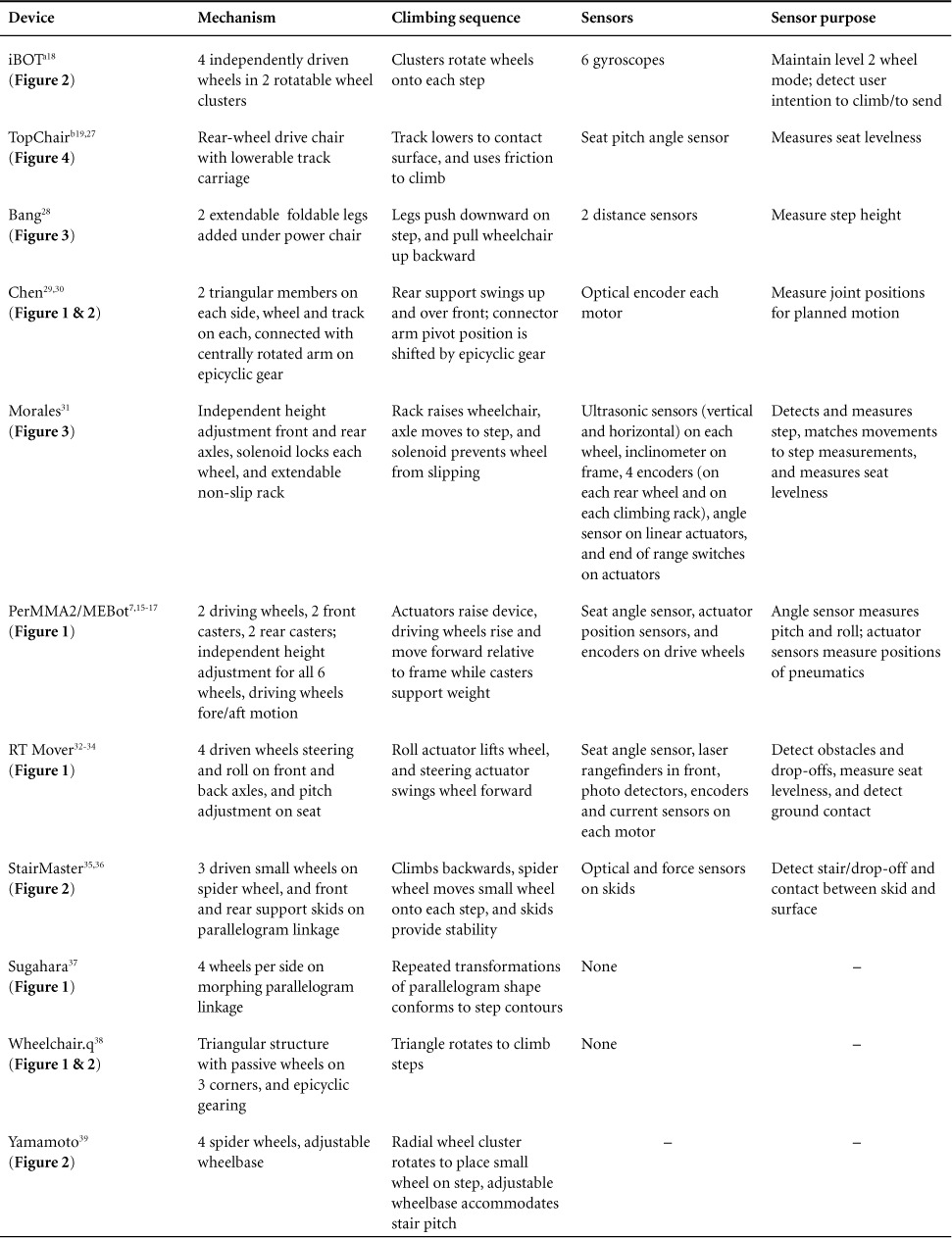

Table 1 summarizes the mechanisms for step climbing, the sequence of actions used to climb a step, the sensors with which each device is equipped, and the functions of those sensors related to step climbing. Mechanisms for step climbing can be divided into 4 categories, with some designs having features from more than one of these categories.

Table 1.

Description of step-climbing power wheelchairs

Table 1.

Description of step-climbing power wheelchairs (CONT.)

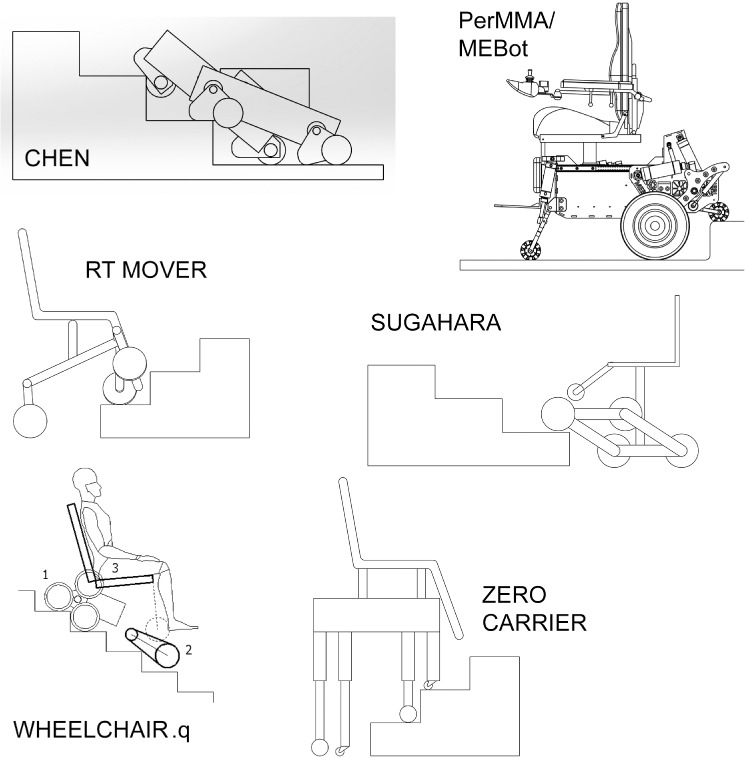

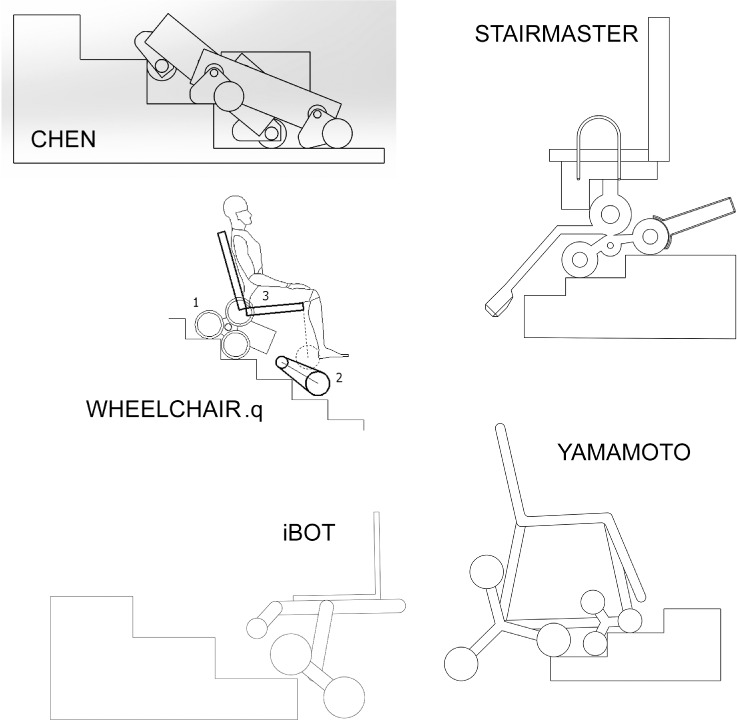

First, leg-wheel hybrids use a wheel or wheels mounted on a structure whose position changes through some means other than a simple rotation, for example, linear height adjustment or a swinging movement requiring multiple joints (Chen, PerMMA/MEBot, RT Mover, Sugihara, Wheelchair.q, Zero Carrier). These leg-wheel designs have a relatively large number of joints and may require complex control algorithms.

A second category uses wheels, which are comprised of small wheels radially mounted on a central hub (Chen, StairMaster, Wheelchair.q, Yamamoto). On level ground, locomotion is provided by the small wheels that are in contact with the ground, and the central hub does not rotate. On discontinuous terrain, the central hub rotates to bring wheels that were previously suspended into contact with the higher or lower surface. To the extent that its 2-wheel clusters rotate around a central axis in stair-climbing mode, the Independence iBOT 4000 has some similarity to these spider wheel designs.

Figure 1.

Leg-wheel hybrid designs.

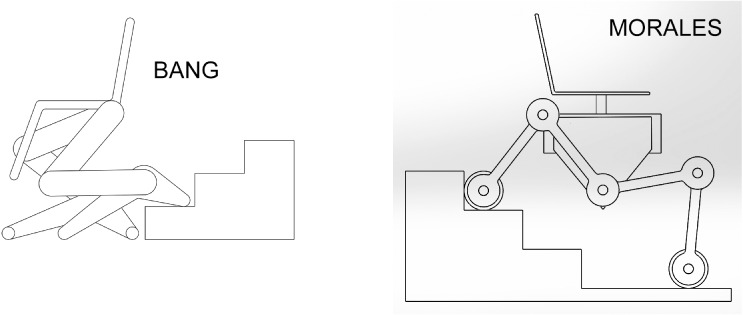

A third approach uses deployable rigid supports that are not intended to slide or roll on the surface in order to lift the device and a secondary mechanism for placing the wheels on the new surface (Bang, Morales).

A fourth category uses crawler tractors – as on military vehicles or earthmoving equipment – that grip the edges of obstacles to pull the device up and over (TopChair, Yu). A single continuous track on each side is simple to construct and does not require a sophisticated control system. This basic means of locomotion can also be modified to permit adapting the track to the contours of the terrain (Yu). However, tracks are mechanically inefficient and often damage the surfaces they traverse.

As can be seen in Table 1, there is a continuum of sensor use. Some designs do not report employing sensors, while others measure the position of each actuated joint. Some designs are capable of sensing their environment to determine when they reach an obstacle and/or the height of that obstacle; these devices may be considered semi-autonomous. Other devices rely upon the user to change modes or directly control the climbing sequence. Because maintaining the seat level while ascending and descending obstacles is important for the comfort, safety, and stability of the user and maintenance of the center of mass over the wheelbase, 7 of the devices incorporate sensors to measure this angle directly.

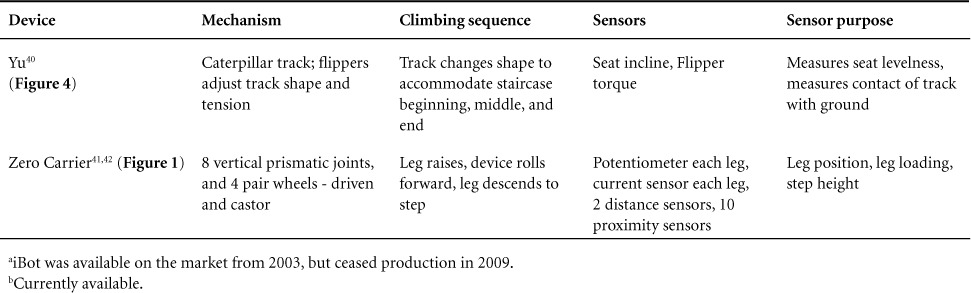

Table 2 lists some of the capabilities of each device. The median accommodated step height was 20 cm, with the maximum step height reported being 25.5 cm. Ten devices reported being capable of climbing continuous stairs, whereas the RT Mover and PerMMA/MEBot only reported being able to climb 2 steps and 1 step, respectively. Five of the devices reported having the additional functionality of being able to maintain the seat level while traveling on continuous inclines; 3 of these reported similar capabilities for cross slopes. For these devices, the terms “pitch” and “roll” refer to the maximum terrain angle at which the device can maintain a level seat posture orientation, respectively, front to back and left to right relative to the device.

Table 2.

Capabilities of step-climbing power wheelchairs

Figure 2.

Spider wheel designs.

Figure 3.

Rigid support designs.

Figure 4.

Crawler tractor designs.

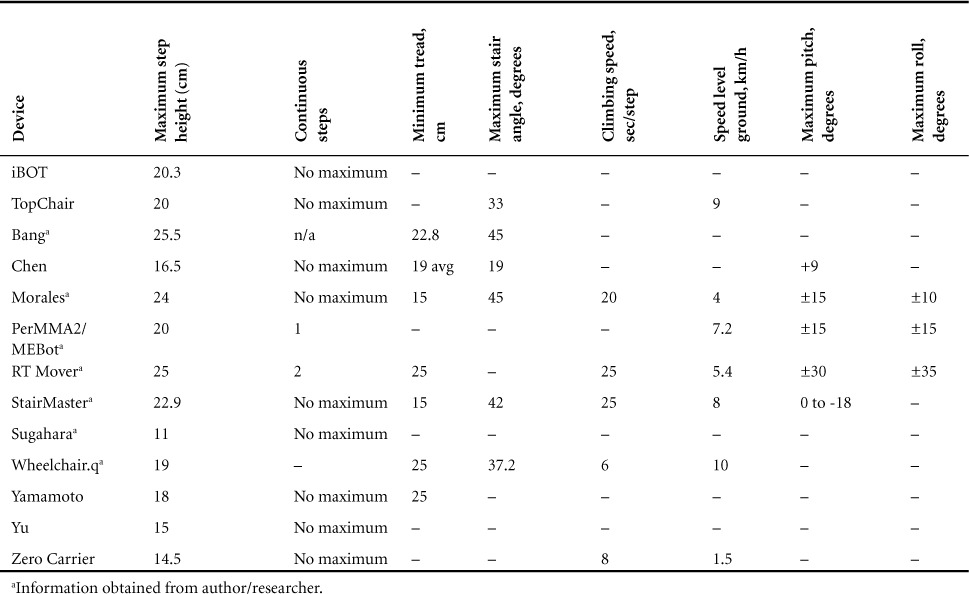

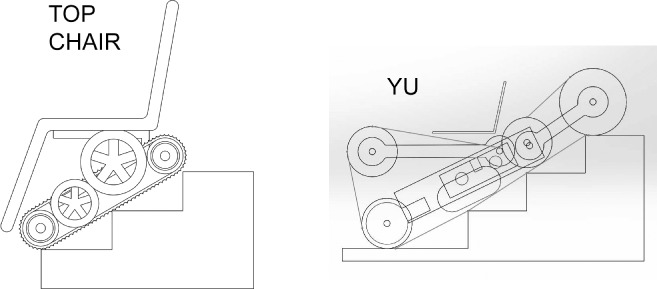

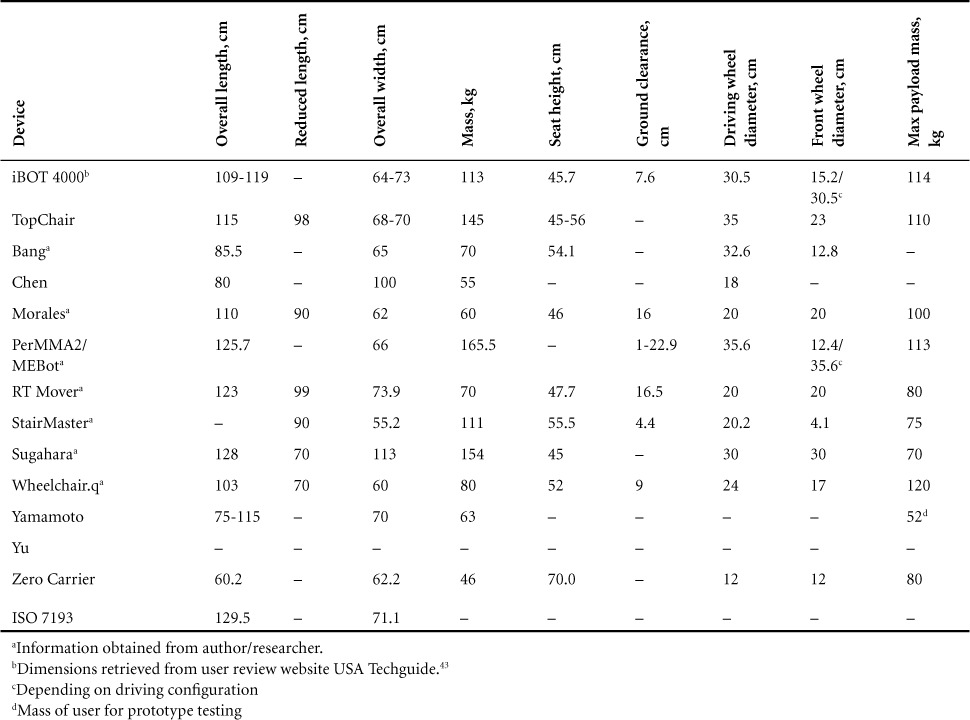

Table 3 gives the dimensions of each device and the maximum length and width for a wheelchair to maintain good indoor maneuverability as recommended in the International Organization for Standards (ISO) 7193 standard, which is 129.5 cm × 71.1 cm (length × width). As measurement procedures were not outlined in the examined articles, it is possible that the measurements reported by researchers may not have been made in the same way, that is, according to the detailed procedures for measuring wheelchairs given in the ISO 7176-05 standard, which specifies the features on the wheelchair that constitute the endpoints for each measurement. Of the devices reporting length, none exceeded ISO 7193. Only 3 exceeded in width (Chen, RT Mover, Sugihara), with one of those exceeding the maximum recommended slightly (RT Mover). There was a range in device weights, and 3 of the devices (TopChair, Sugihara, PerMMA/MEBot) were nearly twice as heavy as the average of the other designs; the complete rehabilitation seating system on the MEBot is partly responsible for its increased weight.

Table 3.

Dimensions of step-climbing power wheelchairs

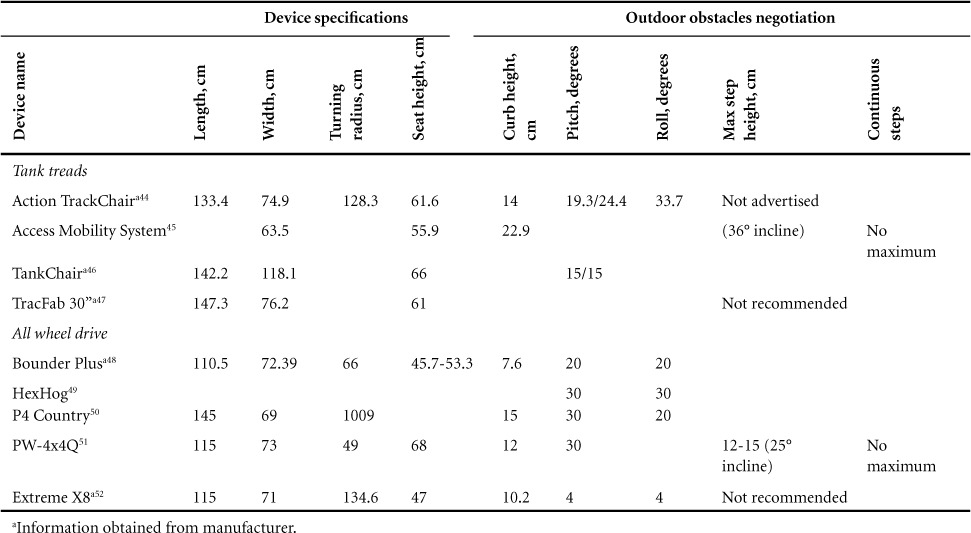

Table 4 presents data on some of the rough terrain wheelchairs that are, or have been, available on the market. These wheelchairs are divided into 2 groups: those that use crawler tracks and those that use large wheels with all-wheel drive. Both approaches, while effective for many outdoor terrains, are inefficient for providing locomotion, tend to limit indoor maneuverability, and can damage the surfaces they traverse. We also note that manufacturer advertised claims of capabilities may not be wholly reliable.

Table 4.

Data for other rough terrain wheelchairs

Although the ability to traverse curbs and stairs can enhance mobility and independence for wheelchair users, these features should not come at the expense of efficient locomotion over level terrain or indoor maneuverability. Considering that a typical walking speed is 4.0 km/h (2.5 mph),14 the speed of some devices over level ground is so slow as to be impractical for use as a primary mobility aid (Morales, Zero Carrier). The small wheels on many designs would impede progress of the device over bumpy terrain, whether causing it to execute an obstacle negotiating sequence or bringing the device to a halt.

Indoor maneuverability is another key function of a mobility device. Although most of the designs fit within the footprint defined by the ISO 7193 maximum recommended dimensions, all are not equally maneuverable. Many designs are described as being able to turn 360° in place, but that does not necessarily indicate ease of moving in tight spaces. For example, making a 90° turn at the intersection of 2 hallways could require stopping, turning 90°, then proceeding, rather than turning in an arc around the corner. Additionally, some turning methods, such as 4-wheel drive with fixed wheel positions or crawler tracks, require skidding of the driving elements against the ground, leading to damage of floors and carpets. These caveats on indoor maneuverability and possible damage to floors also apply to the rough terrain wheelchairs that are currently on the market.

Power seat functions of tilt, recline, and leg elevation are prescribed for many power wheelchair users. These seating adjustments provide postural support that can be adapted to different activities of daily living, such as reaching or transfers, increased sitting comfort, and relief of pressure that could otherwise damage skin integrity and lead to pressure sores. Of the referenced devices, only 2 considered the addition of powered seat functions (PerMMA/MEBot, Stairmaster). This fact is particularly significant, as the iBOT's lack of support for power seat functions was one of the factors preventing it from getting the higher level of reimbursement from Medicare for group 3 power wheelchairs.

Device evaluations

The literature only reflects preliminary, proof-of-concept-type testing, which makes judging the practical utility of any of these devices difficult. Of the 13 devices identified, 11 appear only to have been tested in highly structured environments. It is, therefore, unclear how well their mechanisms would cope with variations in step height, tread depth, riser slant, or step edge geometry (eg, rounded, eroded, etc) that would be encountered in daily use. For those designs that employ sensors, differences in surface reflectivity for infrared or laser rangefinders and poor contrast for optical sensors could give erroneous readings that could cause the system to misjudge obstacle height or completely fail to detect a drop-off.

Furthermore, there is no indication that the testing of any of these research prototypes (a group that includes all cited devices except the iBOT and the TopChair) has been done with individuals with disabilities. A clinical study of the PerMMA2 used subjects with disabilities, but it was only to test the manipulator arm functions.15 Moreover, only the PerMMA/MEBot refers to involving individuals with disabilities in the design process.7,16,17 Together, these omissions make it difficult to predict the extent to which any eventual product may be adopted.

Clinical evaluation

The 2 largest clinical studies of step-climbing wheelchairs both commented on the lack of a standardized test to evaluate the efficacy of advanced wheelchair systems. Consequently, each study sets forth its own test criteria in scoring system.

In Uustal and Minkel's study of the iBOT,18 the Community Driving Test consisted of 15 tasks performed by subjects in their usual living and working environment. Of the 15 tasks, 4 – up interior stair, down interior stair, up exterior stair, and down exterior stair – would be impossible to perform safely in any standard EPW, and 6 others – climbs up curb, climbs down curb, one step entry, one step exit, negotiate uneven terrain, and retrieve book off high shelf – would either be difficult or impossible to perform in a standard EPW depending on the specific measurements of the obstacles, although retrieving a book off a high shelf could be facilitated by a wheelchair with seat elevation or standing function. The tasks were scored from 0 to 6 with 0 indicating that the subject could not or would not perform the task; 1 to 3 measuring the exertion of an assistant who helped to perform the task, with 1 being maximum exertion and 3 being minimal exertion; and 4 to 6 measuring the exertion of the subject, with 4 being maximum exertion and 6 being minimal exertion. Although these tasks are arguably representative of tasks performed by ambulatory persons in similar environments, the Community Driving Test clearly favors EPW with the specific characteristics of the iBOT – curb climbing, stair climbing, and seat elevation.

In Laffont et al's study of the TopChair,19 the simulated outdoor circuit consisted of a variety of slopes of up to 10° and driving with one set of wheels on level ground while the other was on a curved surface. No soft or irregular surfaces were included; on the outdoor driving circuit, the TopChair was only evaluated in its wheeled operation mode. Hence, the test provided little opportunity for the TopChair's advanced functions to demonstrate an advantage over the conventional EPW (Invacare Storm3) used as comparison. The same report did include trials of climbing steps with the TopChair that assessed this feature.

A number of driving assessments have been developed and adopted in research and clinical practice to measure the abilities of wheelchair users. The Power Mobility Indoor Driving Assessment (PIDA) and Power Mobility Community Driving Assessment (PCDA) evaluate, respectively, maneuvering indoors and the ability to overcome environmental obstacles.20,21 The widely administered Wheelchair Skills Test is more often used with manual wheelchairs, but it has also been used with power wheelchairs.22,23 Version 4.2 of the Wheelchair Skills Test for power wheelchairs includes propulsion across uneven surfaces, inclines, a vertical obstacle similar to a curb or threshold, and maneuvering up and down a 5 cm curb.24 Another tool, the Obstacle Course Assessment of Wheelchair User Performance, requires construction of ramps at multiple inclinations up to 7° a section of gravel surface, and the highest individual step height of these assessments at 15 cm (6 in.).25 More recently, Kamaraj et al have developed the Power Mobility Clinical Driving Assessment,26 which includes inclines, cross slopes, and ADA curb cuts but no steps. In keeping with the assessments' focus on safety and training, the scores rely primarily on the evaluations of the administering clinician.

Drawing upon the preceding studies and further input from clinicians, users, and researchers, a driving test should be developed in which tasks and scoring are specifically tailored to the evaluation of devices in negotiating real-world tasks while minimizing the influence of operator skills. The test should include terrain and environmental barriers that are not easily negotiated by a typical EPW to demonstrate clinically significant increases in independence. The test should also include tasks that can demonstrate performance relative to conventional EPWs in customary usage, such as traversal over level ground or maneuvering through doorways. Further, it is important that such terrains and obstacles be standardized and quantifiable, so that equivalent tests can be undertaken at different times, and in different locations, whether in the context of benchtop testing or clinical trials. As the clinical benefit of any assistive technology is based on a variety of factors, a multidimensional scoring rubric may include some combination of task completions, time, observer evaluation, and user comfort with the device.

Conclusion

A number of wheelchairs capable of climbing curbs or steps are under current development. These devices represent a variety of approaches to the tasks of climbing a single step or continuous stairs, including leg-wheel hybrid systems, spider wheels, additional structures for lifting, and crawler tractors. Control systems range from relying on no sensors at all for detecting features of the environment to closely monitoring the position of each actuated structure and estimating features of the environment. The majority of the identified designs are capable of climbing continuous stairs. However, even though all the devices included in the review reported the ability to overcome environmental barriers that are a hindrance to current EPWs, not all are as efficient as current EPWs when traveling over level ground and their suitability for maneuvering indoors has not been demonstrated.

Testing for the described prototypes was reported to have taken place in highly controlled environments, and most frequently testing did not include end-users representing the group for which the product was designed. Test results are not comparable across reports. The 2 largest clinical studies of step-climbing wheelchairs to date either gave little opportunity for the advanced wheelchair to demonstrate its advantage over current offerings or did not provide details of the tests that were specific enough to be used by other researchers in trying to compare device functionality. It is, therefore, important to develop a well-specified driving evaluation that is representative of the situations most encountered by wheelchair users.

With only one of the devices currently available on the market, there is a need to refine current prototypes to make them usable for the wide variety of terrains encountered by wheelchair users, make their mechanisms and sensors reliable, and create a final design that can be manufactured at a reasonable cost. Opportunities still exist for new research – either by expanding upon the reported designs or by taking an entirely new approach.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Brandon Daveler, Richard Kovacsics, Mike Malloy, Chelsea Young, Dustin Chase, Ethan Serra, and Michael Lain for their assistance with this article. This article was supported in part through grants from the National Science Foundation and the Craig H. Nielsen Foundation. Its contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brault MW. Americans with Disabilities: 2010. Household Economic Studies. Washington DC: US Department of Commerce, US Census Bureau; 2012: 70– 131. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ståhl A, Iwarsson S, Brandt Å.. Older people's use of powered wheelchairs for activity and participation. J Rehabil Med. 2004; 36( 2): 70– 77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. . Guidelines on the provision of manual wheelchairs in less-resourced settings. 2016. http://www.who.int/disabilities/publications/technology/wheelchairguidelines/en/. [PubMed]

- 4. Cooper RA, Cooper R, Boninger ML.. Trends and issues in wheelchair technologies. Assist Technol. 2008; 20( 2): 61– 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Edwards K, McCluskey A.. A survey of adult power wheelchair and scooter users. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2010; 5( 6): 411– 419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ding D, Cooper RA.. Electric powered wheelchairs. IEEE Control Syst. 2005; 25( 2): 22– 34. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Daveler B, Salatin B, Grindle GG, Candiotti J, Wang H, Cooper RA.. Participatory design and validation of mobility enhancement robotic wheelchair. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015; 52( 6): 739– 750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xiang H, Chany AM, Smith GA.. Wheelchair related injuries treated in US emergency departments. Inj Prevent. 2006; 12( 1): 8– 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gaal RP, Rebholtz N, Hotchkiss RD, Pfaelzer PF.. Wheelchair rider injuries: Causes and consequences for wheelchair design and selection. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1997; 34( 1): 58– 71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ummat S, Kirby RL.. Nonfatal wheelchair-related accidents reported to the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1994; 73( 3): 163– 167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen W-Y, Jang Y, Wang J-D, . et al. Wheelchair-related accidents: Relationship with wheelchair-using behavior in active community wheelchair users. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011; 92( 6): 892– 898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nelson AL, Groer S, Palacios P, . et al. Wheelchair-related falls in veterans with spinal cord injury residing in the community: A prospective cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010; 91( 8): 1166– 1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. US Food and Drug Administraton. . Physical medicine devices; reclassification of stair-climbing wheelchairs. Final order. Fed Regist. 2014: 20779– 20783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Average walking speed. WolframAlpha website. 2016. http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=Average+walking+speed.

- 15. Wang H, Xu J, Grindle G, . et al. Performance evaluation of the Personal Mobility and Manipulation Appliance (PerMMA). Med Eng Physics. 2013; 35( 11): 1613– 1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Candiotti J, Wang H, Chung C-S, . et al. Design and evaluation of a seat orientation controller during uneven terrain driving. Med Eng Physics. 2016; 38( 3): 241– 247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang H, Candiotti J, Shino M, . et al. Development of an advanced mobile base for personal mobility and manipulation appliance generation II robotic wheelchair. J Spinal Cord Med. 2013; 36( 4): 333– 346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Uustal H, Minkel JL.. Study of the independence IBOT 3000 mobility system: An innovative power mobility device, during use in community environments. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004; 85( 12): 2002– 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laffont I, Guillon B, Fermanian C, . et al. Evaluation of a stair-climbing power wheelchair in 25 people with tetraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008; 89( 10): 1958– 1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dawson D, Chan R, Kaiserman E.. Development of the power-mobility indoor driving assessment for residents of long-term care facilities: A preliminary report. Can J Occup Ther. 1994; 61( 5): 269– 276. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Letts L, Dawson D, Kaiserman-Goldenstein E.. Development of the power-mobility community driving assessment. Can J Occup Ther. 1998; 11( 3): 123– 129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kirby RL, Swuste J, Dupuis DJ, MacLeod DA, Monroe R.. The Wheelchair Skills Test: A pilot study of a new outcome measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002; 83( 1): 10– 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mountain AD, Kirby RL, Eskes GA, . et al. Ability of people with stroke to learn powered wheelchair skills: A pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010; 91( 4): 596– 601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dalhousie University. . Wheelchair skills program (4.2) forms. 2013. http://www.wheelchairskillsprogram.ca/eng/wspforms.php.

- 25. Routhier F, Vincent C, Desrosiers J, Nadeau S, Guerette C.. Development of an obstacle course assessment of wheelchair user performance (OCAWUP): A content validity study. Tech Disabil. 2004; 16( 1): 19– 31 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kamaraj DC, Dicianno BE, Cooper RA.. A participatory approach to develop the power mobility screening tool and the power mobility clinical driving assessment tool. BioMed Res Int. 2014; 2014: 1– 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. TopChair wheelchair. TopChair website. 2014. http://www.topchair.fr/en/.

- 28. Two-legged stair-climbing wheelchair and its stair dimension measurement using distance sensors. Presented at: IEEE 11th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS); October 26–29, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen C-T, Liao T-T, Pham H-V.. On climbing winding stairs for a robotic wheelchair. World Acad Sci Eng Technol. 2010: 253– 258. http://waset.org/publications/4096/on-climbing-winding-stairs-for-a-robotic-wheelchair [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen C-T, Feng C-C, Hsieh Y-A.. Design and realization of a mobile wheelchair robot for all terrains. Adv Robot. 2003; 17( 8): 739– 760. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morales R, Gonzalez A, Feliu V, Pintado P.. Environment adaptation of a new staircase-climbing wheelchair. Auton Robot. 2007; 23( 4): 275– 292. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nakajima S. RT-Mover: A rough terrain mobile robot with a simple leg-wheel hybrid mechanism. Int J Robot Res. 2011; 30( 13): 1609– 1626 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nakajima S. Proposal of a personal mobility vehicle capable of traversing rough terrain. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2014; 9( 3): 248– 259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakajima S. Gait algorithm of personal mobility vehicle for negotiating obstacles. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2014; 9( 2): 151– 163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cox K. Development of a wheelchair with access for most users and places. Presented at: RESNA Annual Conference; 2014; Indianapolis, Indiana. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cox KR. Battery powered stair-climbing wheelchair. Google Patents; 2002.

- 37. A novel stair-climbing wheelchair with transformable wheeled four-bar linkages. Presented at: International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); October 18–22, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Quaglia G, Franco W, Oderio R.. Wheelchair.q, a motorized wheelchair with stair climbing ability. Mechanism Machine Theory. 2011; 46( 11): 1601– 1609. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Development of stair locomotive wheelchair with adjustable wheelbase. Proceedings of SICE Annual Conference (SICE); August 20–23, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Track tension optimization for stair-climbing of a wheelchair robot with Variable Geometry Single Tracked Mechanism. Presented at: International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO); December 7–11, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Research on leg-wheel hybrid stair-climbing robot, Zero Carrier. Presented at: International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics; August 22–26, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Actualization of safe and stable stair climbing and three-dimensional locomotion for wheelchair. Presented at: International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, IROS; August 2–6, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 43. TechGuide. Wheelchair review and assistive technology guide. Independence Technology, L.l.c Ibot 4000 (power wheelchairs); Independence Technology, L.l.c Ibot 4000 (Power Wheelchairs). 2015. United Spinal Association website. http://www.usatechguide.org/itemreview.php?itemid=1467.

- 44. Action Manufacturing Inc. . Action Trackchair. 2016. http://www.actiontrackchair.com/ActionTrackchairNTModel-Specs/Default.aspx#.WBfDGfkrKUk.

- 45. Fisher LM. Wheelchair with treads climbs stairs and curbs. The New York Times. June 21, 1989. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1989/06/21/business/business-technology-wheelchair-with-treads-climbs-stairs-and-curbs.html [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tankchair LLC. . The Original Tankchair. http://www.tankchair.com/tankchair/.

- 47. Trac Fabrication LLC. . TracFab. 2016. http://www.tracfab.com/.

- 48. 21st Century Scientific, Inc. . Bounder Plus Power Wheelchair with high volume, low pressure off road package (HVLP OR). http://www.wheelchairs.com/offroad.html.

- 49. Da-Vinci Wheelchairs Ltd. . HexHog. 2016. http://www.hexhog.com/specification.

- 50. 4poWer4 sprl. The P4 Country 4x4 wheelchair is great for mountain paths. 2010. http://www.fourpowerfour.com/The-new-4x4-wheelchair-in-the-mountains.asp.

- 51. Wheelchair88. Foldawheel PW-4X4Q stair climbing wheelchair. 2016. https://www.wheelchair88.com/product/pw-4x4q/.

- 52. Innovation in Motion. Extreme X8. http://www.mobility-usa.com/extreme-x8--4x4.html.