Summary

High-dose rituximab (HD-R) combined with carmustine, cytarabine, etoposide, and melphalan (BEAM) and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) was effective and tolerable in a single-arm prospective study of relapsed aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (R-NHL). We performed a randomized phase 2 study comparing HD-R vs. standard-dose rituximab (SD-R) in R-NHL. Ninety three patients were randomized to HD-R (1,000 mg/m2) (n=42) or SD-R (375 mg/m2) (n=51) administered on post-transplant days +1 and +8, using a Bayesian adaptive algorithm. The 2 treatment arms were balanced in regards to patient demographic and clinical characteristics. At a median follow-up of 7.92 years, the 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were 40% and 48%, respectively. We found no statistically significant differences between HD-R and SD-R in 5-year DFS (36% vs 43%; p=0.205) and OS (43% vs 52%; p=0.392). In multivariate analyses, only disease status before ASCT [residual disease vs complete remission (CR)] (HR 1.79, 95% CI: 1.08 – 2.95) and number of prior treatments received (>2 vs ≤2 lines of treatment) (HR 1.89, 95% CI: 1.13 – 3.18) were associated with worse DFS, as well as OS. Patients who had SCT while in CR or who received ≤2 lines of treatment prior to SCT had better 5-year OS (57% vs 35%; P=0.02 and 54% vs 30%, P=0.001, respectively) in both arms. No differences in engraftments or adverse events were noted in the 2 arms. When combined with BEAM and ASCT in relapsed aggressive B-cell NHL, HD-R provided no DFS or OS advantage over SD-R.

Keywords: Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, NHLs, BEAM, rituximab, autologous transplant

Introduction

High-dose therapy (HDT) and autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT) remain the standard treatment for relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and other aggressive B-cell Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL). In the pre-rituximab era, the Parma Study was first to report the survival advantage of the HDT and ASCT compared to conventional chemotherapy.(Philip, et al 1995) However, relapse after ASCT remains the main cause of death, (Gisselbrecht, et al 2012) and there is an unmet need to further explore novel approaches to improve disease control rates after transplant.

Several studies incorporated rituximab in the salvage and conditioning regimens prior to ASCT or for maintenance therapy. These studies showed conflicting results when rituximab was added to salvage regimens for relapsed patients who had received rituximab in the initial frontline treatment.(Feugier, et al 2005, Gisselbrecht, et al 2010, Gisselbrecht, et al 2012, Mounier, et al 2012, Rovira, et al 2015, Vellenga, et al 2008) Furthermore, there have been few randomized studies comparing salvage regimens used in the relapse setting, with no regimen shown to be superior.(Crump, et al 2014, Gisselbrecht, et al 2010) There is also limited evidence to support the superiority of any of the commonly used conditioning regimens before ASCT. Carmustine, cytarabine, etoposide, and melphalan (BEAM) is the preferred regimen by many institutions, due to similar efficacy and acceptable safety profile. (Isidori, et al 2015)

Little success has been achieved to improve HDT regimens over last 3 decades. None of the conditioning regimens have been compared prospectively in randomized studies, and evidence is mostly based on observational retrospective studies or single arm prospective trials.

High-dose rituximab (HD-R; 1000 mg/m2) in combination with BEAM and ASCT was effective and tolerable in a single-arm prospective study for relapsed/refractory DLBCL and aggressive B-cell NHLs.(Khouri, et al 2005) HD-R was given to all patients (n=67) on days 1 and 8 post stem cell infusion. Compared to historical controls (i.e. BEAM alone without rituximab), both overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) rates were significantly improved in the HD-R arm.

We present in this report the first and largest randomized phase 2 clinical trial to-date comparing efficacy and safety of HD-R vs. standard-dose rituximab (SD-R) combined with BEAM in relapsed and refractory B-cell NHLs.

Methods

Study Design

This was an open-label prospective, single center, randomized, phase II study in patients with relapsed/refractory DLBCL or aggressive B-cell NHL comparing two different doses of rituximab combined with high-dose BEAM chemotherapy. The primary endpoint was disease-free survival (DFS), defined as time from transplantation to disease relapse/progression or death. OS and safety analysis were secondary endpoints. OS was calculated from time of transplantation to death or last follow-up.

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. All patients signed an informed consent for the study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00472056).

Patient Eligibility

Patients at age ≤80 years with histologically proven diffuse large B-cell, transformed follicular or CD20-positive B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas that had relapsed after conventional chemotherapy were eligible for enrollment. Patients were required to have chemosensitive disease to salvage chemotherapy and less than 5% bone marrow involvement with lymphoma at the time of enrollment. Other eligibility criteria included a Zubrod performance status score of <2 and negative test for pregnancy, HIV, hepatitis B surface antigen, and hepatitis C antibody. Exclusion criteria were active central nervous system disease, <3 weeks from last chemotherapy, left ventricular ejection fraction less than 40%, corrected DLCO <50%, serum creatinine > than 1.6 mg/dl, serum bilirubin > 1.5 mg/dl, serum transaminases > 2 times upper normal level, and failure to collect more than 2 × 106 CD 34+ stem cells/kg body weight.

Treatment

Stem cell mobilization

Stem cells were mobilized after the penultimate or final cycle of salvage chemotherapy followed by filgrastim 6 mcg/kg/day (rounded to nearest vial size) or any available mobilization study per investigator choice.

High-dose chemotherapy and stem cell infusion

For patients 65 years of age or younger, BEAM was given in following dosages and schedule: Carmustine 300 mg/ m2 IV over 1 hour on day -6, cytarabine 200 mg/ m2 IV twice a day on days -5 through -2 (total 8 doses), etoposide 200 mg/ m2 IV twice a day on days -5 through -2 (total 8 doses), and melphalan 140 mg/m2 IV on day -1. For patients older than 65 years of age, dose-reduced BEAM was given: Carmustine 300 mg/ m2 IV over 1 hour on day -6, cytarabine 100 mg/m2 IV twice a day on days -5 through -2 (total 8 doses), etoposide 100 mg/m2 IV twice a day on days -5 through -2 (total 8 doses), and melphalan 140 mg/ m2 IV on day -1.

For autologous stem cell rescue after HDT, a median of 4.92 million/kg (range 2.80–25.01) CD34-positive cells were infused on day 0 of transplant. HD-R 1000 mg/m2 or SD-R 375 mg/m2 IV according to randomized arm were given on days +1 and +8 after stem cell infusion. Patients received G-CSF 5 mcg/kg/day subcutaneously, beginning on day +1 until hematologic recovery. All patients received concomitant supportive care according to established institutional bone marrow transplant guidelines at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Safety and Response Assessments

Toxicity grades were based on Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3 (CTCAE v 3.0). All patients underwent the following baseline staging procedures: physical examination, CBC with differential count, serum chemistry panel, quantitative immunoglobulins, serum beta2-microglobulin measurement, urine analysis, pregnancy test for patients at child bearing age, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, review of pathology slides, computed tomography (CT) of the neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis. Gallium scanning and/or PET scan were done as clinically indicated. Re-staging studies included CT scans at day 30 after ASCT, and then at 3 months and 6 months, and thereafter every 6 months for 3 years (unless clinically indicated) and then annually while patient on study. Bone marrow biopsy was repeated only if indicated to document remission. If a gallium or PET scan was performed at baseline and was positive, then it was repeated after transplant to confirm remission. Responses were assessed and defined as previously described by Cheson et al.(Cheson, et al 1999)

Hematopoietic engraftment post-transplant recovery was determined by neutrophil count recovery, defined as the first of 3 consecutive days when the absolute neutrophil count was >500 cells/μL, and platelet count recovery defined as the first day after transplantation when the platelet count was >20,000/μL (independent of platelet transfusions).

Statistical Methods

Patients were randomized between the two study arms using a Bayesian adaptive algorithm.(Berry and Eick 1995) We assumed that DFS for each treatment arm follows the same Weibull distribution, with a parameter for age group (< 65, ≥ 65). The prior distributions of the Weibull parameters were chosen so that the median DFS was 26 months for patients younger than 65 and 14 months for patients 65 and older. The prior distributions were updated with follow-up and event data throughout the trial to obtain posterior distributions of DFS for each treatment, adjusted for age. For each patient the randomization probability for a treatment was the posterior probability that it had longer median DFS than the other treatment. Preplanned sample size was 100 patients; however, the trial was closed to new patient entry by the MD Anderson Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) after 93 patients had been enrolled because it was considered extremely unlikely that either treatment arm would have statistically superior DFS should the trial enroll the full complement of the originally planned 100 patients.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the median time to event including DFS, EFS, and OS, and 95% CIs were calculated. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to model DFS and OS as a function of treatment while adjusting for age and all significant variables at a P <0.15 in univariate analysis, and it was used to calculate the hazard ratios between the two treatment arms. All reported P values are two-sided, and statistical significance was defined as P <.05. The statistical analysis was performed using SAS® software version 9.3.

Results

Patient Clinical Characteristics

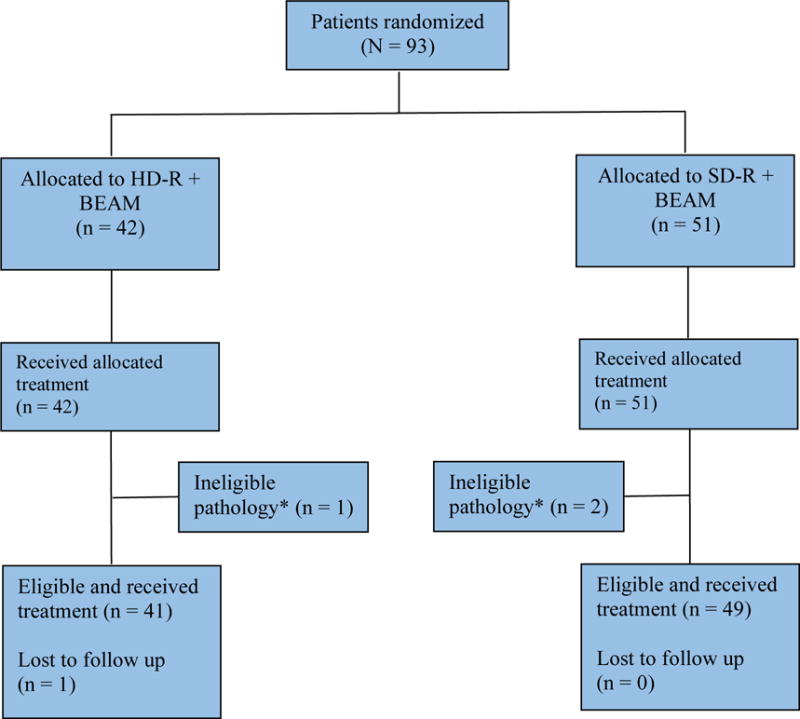

A total of 93 patients were enrolled in the study period between 03/2005 and 04/2009 (Figure 1). Patients were randomly assigned to HD-R (n = 42) or SD-R (n = 51). The median age for the entire group was 63 years (range, 6.0–75) with male predominance (71% males). A total of 38 (41%) patients were 65 years of age or older and all received dose-reduced BEAM. Baseline patient demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Overall, the two arms were well balanced with no statistically significant differences between the two treatment arms with respect to demographic and clinical characteristics. A total of 53 (57%) patients had relapsed disease from a de novo DLBCL and 40 (43%) had other aggressive B-cell NHLs (Table 1).

Figure 1. Consort diagram showing the flow of participants at each stage of the randomized trial.

Abbreviations: BEAM, carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan; HD-R, high-dose rituximab; SD-R, standard-dose rituximab.

*Patients with unclassified grade 3 follicular lymphoma but with high-grade pathologic and/or clinical features were considered aggressive B-cell lymphomas.

Table 1.

Patient and disease characteristics

| Standard-Dose

Rituximab (n=51) |

High-Dose Rituximab (n=42) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | ||

| Age | 0.297 | ||

| Median, in years (range) | 63 (7–75) |

63 (32–75) |

|

|

| |||

| Age Group | 0.436 | ||

| < 65 | 32 (62.8) | 23 (54.8) | |

| ≥ 65 | 19 (37.3) | 19 (45.2) | |

|

| |||

| Gender | 0.407 | ||

| Female | 13 (25.5) | 14 (33.3) | |

| Male | 38 (74.5) | 28 (66.7) | |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.576 | ||

| Black | 2 (3.9) | 2 (4.8) | |

| Hispanic | 8 (15.7) | 4 (9.5) | |

| White / Non-Hispanic | 39 (76.5) | 36 (85.7) | |

| Other / Unknown | 2 (3.9) | 0 (0) | |

|

| |||

| Histology | 0.623 | ||

| DE Novo DLBCL | 27 (52.9) | 26 (61.9) | |

| Transformed B-Cell NHL | 12 (23.5) | 10 (23.8) | |

| Discordant | 4 (7.8) | 3 (7.1) | |

| Other | 8 (15.7) | 3 (7.1) | |

|

| |||

| Stage | 0.798 | ||

| I–II | 12 (23.6) | 11 (26.2) | |

| III–IV | 38 (74.5) | 30 (71.4) | |

|

| |||

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 1 (2.4) | |

| IPI at Transplantation | 0.763 | ||

| ≤ 1 | 40 (80) | 33 (82.5) | |

| > 1 | 10 (20) | 7 (17.5) | |

|

| |||

| Unknown | 1 | 2 | |

| Disease Status Prior to Transplant | 0.496 | ||

| CR/CRu | 28 (54.9) | 26 (61.9) | |

| PR/SD | 23 (45.1) | 16 (38.1) | |

|

| |||

| Prior lines of treatment | 0.711 | ||

| ≤ 2 | 37 (72.6) | 29 (69.0) | |

| > 2 | 14 (27.4) | 13 (31.0) | |

|

| |||

| Time from diagnosis to Transplant | 0.685 | ||

| > 18 months | 36 (70.6) | 28 (66.7) | |

| ≤ 18 months | 15 (29.4) | 14 (33.3) | |

Abbreviations: CR/CRu, complete remission/complete remission unconfirmed; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; HR, hazard ratio; No., number; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; PR/SD, partial response/stable disease.

Efficacy

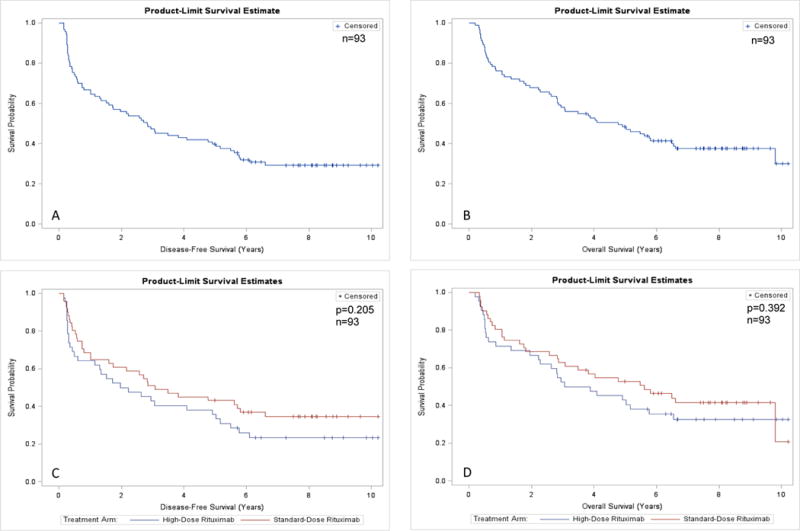

The median follow-up of the surviving patients at last follow-up was 7.92 (range, 3.76–10.23) years. The 5-year DFS and 5-year OS for the study group were 40% (95% CI, 29% to 48%) and 48% (95% CI, 37% to 57%), respectively (Figure 2A–B). There was no statistically significant difference between the HD-R and SD-R arms in 5-year DFS (36% vs 43%, respectively; p = 0.205) (Figure 2C). Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in the 5-year OS between the HD-R and SD-R arms (43% vs 52%; P = 0.392) (Figure 2D). Among patients <65 years, the 5-year DFS and OS were 45% and 53%, respectively, compared to 32% (p = 0.113) and 42% (p = 0.039) for those at age 65 or older. There was no benefit from HD-R treatment in either age group (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Survival of patients after autologous stem cell transplantation (n=93). (A) Disease-free survival (DFS) of all study patients. (B) Overall survival (OS) of all study patients. (C) DFS by study arm. (D) OS by study arm.

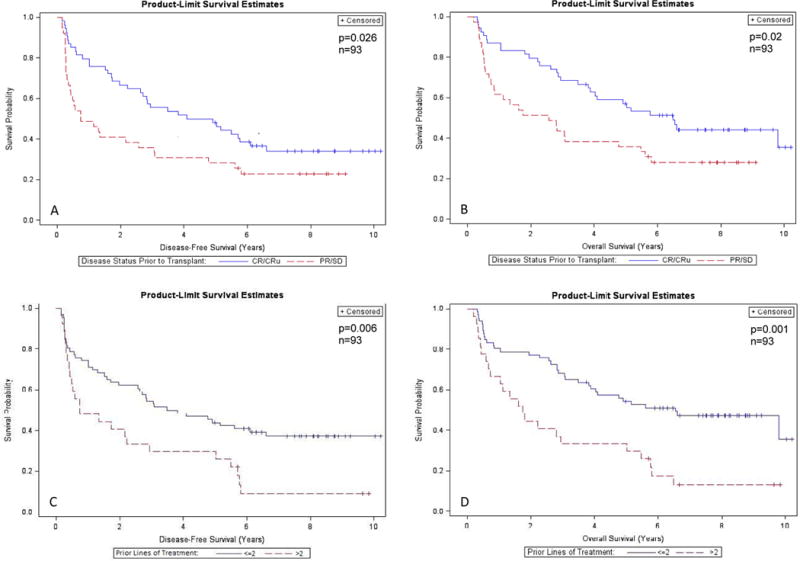

Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed to identify potential prognostic factors (Table 2). The following were examined in univariate analysis: age group, gender, histology, stage, LDH, number of prior lines of treatment, disease status prior to transplant, time from diagnosis to transplant, and treatment arm. Five-year DFS and OS were affected primarily by disease status before ASCT (remission vs no remission) and number of prior lines of treatments received (≤ 2 vs > 2 lines of treatment). Patients who had transplanted while in CR compared to no CR had better 5-year DFS (50% vs 30%, respectively; P=0.026) and OS (57% vs 35%, respectively; P=0.02) (Figure 3A–B). Similarly, those who received ≤2 lines of treatment prior to ASCT compared to >2 lines had significantly better 5-year DFS (45% vs 30%, respectively; P=0.006) and OS (54% vs 30%, respectively; P=0.001) (Figure 3C–D). In the Cox model, patients who had HDC and ASCT while having partial response or stable disease had significantly worse DFS (HR 1.79, 95% CI: 1.08 – 2.95) and OS (HR 1.79, 95% CI 1.05 – 3.06) compared with those with complete remission (CR)/CR unconfirmed (CRu). Similarly, patients with > 2 prior lines of treatment had significantly worse DFS (HR 1.89, 95% CI: 1.13 – 3.18) and OS (HR 2.30, 95% CI 1.34 – 3.94). Age and treatment arm were not statistically significant predictors of DFS and OS on multivariate analysis.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis for disease-free and overall survival

| Covariate | Overall survival |

Disease-free survival

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-Value | HR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| Treatment arm | ||||

| SD-R | 1 | 0.439 | 1 | 0.242 |

| HD-R | 0.81 (0.48 – 1.38) | 0.74 (0.45 – 1.23) | ||

|

| ||||

| Age in years | ||||

| < 65 | 1 | 0.076 | 1 | 0.199 |

| ≥ 65 | 1.60 (0.95 – 2.68) | 1.38 (0.84 – 2.25) | ||

|

| ||||

| Disease status before translant | ||||

| CR/CRu | 1 | 0.032 | 1 | 0.024 |

| PR/SD | 1.79 (1.05 – 3.06) | 1.79 (1.08 – 2.95) | ||

|

| ||||

| No. of prior lines of treatmnet | ||||

| ≤ 2 | 1 | 0.002 | 1 | 0.016 |

| > 2 | 2.30 (1.34 – 3.94) | 1.89 (1.13 – 3.18) | ||

Abbreviations: CR/CRu, complete remission/complete remission unconfirmed; HR, hazard ratio; HD-R, high-dose rituximab; No., number; PR/SD, partial response/stable disease; SD-R, standard-dose rituximab.

Figure 3. Survival of patients after autologous stem cell transplantation according to significant predictive factors (n=93). (A–B) Disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) by disease status prior to transplant. (C–D) DFS and OS by number of prior lines of treatment.

Abbreviations: CR/CRu, complete remission/complete remission unconfirmed; PR/SD, partial response/stable disease.

Subgroup analyses were performed (by age, gender, LDH, histology, disease status prior to transplant, number of prior lines of treatment) to identify any susceptible subgroups may benefit from HD-R. None of the subgroups benefited from HD-R (results are not shown). For patients with DE novo DLBCL (n=53), there was no significant difference in DFS and OS by treatment arm. The 5-year DFS for HD-R and SD-R were 35% and 48%, respectively (P = 0.382), and the 5-year OS rates were 39% and 52% (P = 0.443), respectively (Supplementary Figure 2). Among patients with de novo DLBCL, only 31 patients had enough testing to determine their cell of origin pathologic subtype by Hans’ algorithm;(Hans, et al 2004) 26 had germinal center B-cell (GCB) and 5 had non-GCB type. For the patients with GCB type, we didn’t find any statistically significant differences in survival outcomes by treatment arm.

Engraftment

A median of 5.25 (range 2.95–15.38) and 4.88(range 2.80–25.01) million/kg CD34-postive cells were infused in the HD-R and SD-R study groups, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in engraftment times between the 2 treatment arms. The median time to ANC engraftment (≥500 cells/μL) was 10 (8–12) days for HD-R and 10 (9–17) days for SD-R. The median time for platelet recovery (≥20,000/μL) was 11 (7–42) days for HD-R and 10 (6–106) days for SD-R.

Safety

Adverse event profile was similar in the two arms. Grade 3–4 toxicities are listed in Table 3; a total of 12 grade 3–4 adverse events occurred among 40 patients in the HD-R arm and 13 events in the SD-R arm. Infection rates were similar between both arms. At the time of last follow-up, a total of 58 deaths (62%) had occurred, 28 in the HD-R arm and 30 deaths in the SD-R arm, majority as a result of lymphoma recurrence (30 patients, 15 each in the HD-R arm and the SD-R arm) (Table 4). 11 patients died of second primary malignancy (SPM) and 7 patients died of infection (Table 4). Only one death occurred within 100 days after ASCT in the HD-R, and death was attributed to infection and persistent disease.

Table 3.

Summary of adverse Events of grade 3 or higher

| Adverse Event | Standard-Dose

Rituximab (n=51) |

High-Dose

Rituximab (n=42) |

All Patients (n=93) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Acute Respiratory Failure | ≈ | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Atrial Fibrilation | ≈ | 2 (5) | 2 (2) |

| Bilirubin | 1 (2) | ≈ | 1 (1) |

| Confusion | ≈ | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | ≈ | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Deep Vein Thrombosis | ≈ | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Diarrhea | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 4 (4) |

| Dyspnea | 1 (2) | ≈ | 1 (1) |

| Fever | 1 (2) | ≈ | 1 (1) |

| Hypercalcemia | 1 (2) | ≈ | 1 (1) |

| Infection | ≈ | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Lethargy | 1 (2) | ≈ | 1 (1) |

| Mucositis | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | 3 (3) |

| Nausea | ≈ | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Neuropathic Pain | ≈ | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Neutropenic Fever | 6 (12) | 3 (7) | 9 (10) |

| Intestinal Obstruction | ≈ | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Elevated Alanine Aminotransferase | 2 (4) | ≈ | 2 (2) |

| Skin Rash | ≈ | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

No reported grade 3–4 toxicity.

Table 4.

Causes of death by study arm and for all patients

| Primary Cause of Death | Standard-Dose (n=51) |

High-Dose (n=42) |

All

Patients (n=93) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Relapse/Progressive disease | 15 | 50.00% | 15 | 53.57% | 30 | 51.72% |

|

| ||||||

| Non-relapse mortality | 12 | 40.00% | 10 | 35.71% | 22 | 37.93% |

| Infection | 5 | 2 | 7 | |||

| Second primary malignancy | 5 | 6 | 11 | |||

| Other | 2 | 2 | 4 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Unknown* | 3 | 10.00% | 3 | 10.71% | 6 | 10.35% |

|

| ||||||

| Total | 30 | 100.00% | 28 | 100 | 58 | 100.00% |

Abbreviations: No., number of deaths per study arm; %, percentage of deaths per total per study arm.

For the unknown causes of death, the primary cause of death was not documented. However, one patient in the standard-rituximab group and two patients in the high-dose rituximab group had progressive disease at time of death, and all others with no evidence of disease.

Second Primary Malignancy

After a median follow up of 7.9 years, 18 patients had developed SPM, 8 in the HD-R group and 10 in the SD-R group. The median time to SPM diagnosis was 68 months (range, 16–175 months) from diagnosis date and 33 months (range, 2–69 months) from transplant date. Eight patients had hematologic secondary neoplasm (6 in the HD-R arm), 9 patients had second solid neoplasms (2 in the HD-R), and 1 patient in the SD-R arm developed both myelodysplastic syndrome and lung cancer. A total of 11 deaths were attributed to SPM (6 secondary to hematologic neoplasms), with no apparent differential contribution by study arm (Table 4).

Discussion

This study is the first randomized clinical trial to compare HD-R versus SD-R combined with BEAM in patients with relapsed DLBCL and aggressive transformed B-cell NHLs. After a median follow-up of 7.9 years, the results demonstrated similar short-term and long-term outcomes in regards to DFS, OS, and adverse events in the two treatment groups. Subgroup analysis including age (<65 years versus ≥65 years), gender, histology, pre-transplant disease status, and number of prior lines of treatment didn’t identify any subset that could benefit from HD-R. Disease status before transplant (CR/CRu) and number of prior treatments (≤2 prior treatments) were the only variables to predict an improved outcome with transplantation.

The introduction of rituximab in management of B-cell lymphomas has improved treatment outcomes; however, since rituximab is universally used in the frontline setting in the current era, its role has been questioned when used in combination with salvage therapy in the relapsed setting.(Gisselbrecht, et al 2010, Martin, et al 2008) Rituximab has been used safely in the pre- and post-transplant setting without adverse effects on stem cell mobilization, engraftment, transplant-related toxicities, and mortality, and deemed potentially effective.(Horwitz, et al 2004, Kamezaki, et al 2007, Magni, et al 2000, Tarella, et al 2011, Tarella, et al 2008) It has been hypothesized that pre-transplant rituximab may enhance antitumor effects by sensitizing specific effector cells and modulating immune reconstitution associated with transplant.(Fenske, et al 2009) In the peritransplant setting, it has been suggested that rituximab may reduce tumor-cell contamination and improve molecular remission,(Brugger, et al 2004, Khouri, et al 2005) which may lead to decreased relapse after transplant.

Our results seem less favorable compared to our prior nonrandomized prospective trial investigating of HD-R combined with BEAM in relapsed aggressive B-Cell lymphomas.(Khouri, et al 2005) Rituximab was also given to all patients during chemomobilzation, 1 day before (at 375 mg/m2) and 7 days after chemotherapy (1000 mg/m2). With a shorter median follow up of 20 months, the study by Khouri et al showed impressive 2-year DFS and OS of 67% and 80%, respectively, for patients received HD-R compared to 43% and 53%, respectively, for historical controls without rituximab.(Khouri, et al 2005) An updated analysis was presented recently in an abstract form after a median follow up of 11.8 years showing a 5-year DFS and OS of 62% and 74%, respectively, for patients treated with HD-R.(Khouri, et al 2015) The findings from our randomized trial failed to confirm a dose-response effect of rituximab and demonstrate a benefit of HD-R compared to SD-R and to reproduce the aforementioned results. The fact that all patients in the prior nonrandomized trial had not receive rituximab as part of their frontline therapy likely accounts for the different results between that trial and the present one in a more modern patient population. Additionally, in the study by Khouri et al. all patients received HD-R 7 days after chemomobilization in contrast to current trial where there was heterogeneity in chemomobilization regimens chosen per investigator discretion and not all patients received HD-R after chemomobilization.

Several prognostic factors were analyzed to examine their influence on treatment outcomes and to identify any susceptible groups might benefit from HD-R. On univariate analysis, there was a statistically significant improvement in survival for patients <65 years, however the significance was lost in the multivariate analysis. The only variables were predictive for an improved DFS and OS after transplantation were disease status before SCT and number of prior lines of treatment; this is consistent with other reports.(Chen, et al 2015) Patients who underwent SCT while in CR/CRu and those who had ≤2 lines of prior treatments had the best outcomes. In accordance with other reports,(Khouri, et al 2005, Kuruvilla, et al 2015) univariate and multivariate analyses revealed similar outcomes for relapsed de novo DLBCL and transformed B-cell NHLs.

The safety profile was similar between both study arms. Specifically, there were no increase grade 3–4 infections or treatment-related mortality with HD-R. Likewise, there was no difference in rates of neutrophil and platelet engraftments. The most common cause of death in both study arms was disease relapse; this, along with the aforementioned findings (disease status at transplant and number of prior therapies were predictive for outcomes) highlight the importance of improving salvage regimens to produce better responses prior to SCT, and the need for early referral for transplant. Incorporation of novel agents into salvage regimens and the recent introduction of cellular therapy into management of relapsed aggressive B-cell lymphomas are very promising investigational areas for potential improvement in transplantation outcomes.

In summary, high-dose rituximab was well tolerated; however, we found no statistically significant differences between HD-R and SD-R when combined with BEAM in relapsed B-Cell aggressive NHLs in terms of DFS and OS. Pre-transplant disease status and numbers of treatments prior to transplant were identified as the only significant predictors for prognosis.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 2. Survival of patients after autologous stem cell transplantation by disease histology (n=93). (A–B) Disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) by disease histology. (C–D) DFS and OS by study arm among patients with de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Supplementary Figure 1. Survival of patients after autologous stem cell transplantation by age-group (n=93). (A–B) Disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) by age-group. (C–D) DFS and OS by study arm among patients at age 65 years or older. (E–F) DFS and OS by study arm among patients younger than 65 years old.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Authorship:

Contributions: C.H. conceived and designed research; S.A.S. performed statistical analysis; S.A.S.and C.H. analyzed and interpreted data; S.A.S. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; C.H. contributed to the manuscript writing and edited the manuscript; S.L. and F.M contributed to data collection. U.R.P., M.H.Q., A.A., P.K., P.A., Y.N., R.J, E.S., R.E.C., and C.H. contributed to patient care. S.A.S., S.L., U.R.P., M.H.Q., S.LC., F.M., A.A., P.K., P.A., Y.N., R.J, E.S., R.E.C., and C.H. critically reviewed and edited the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Berry DA, Eick SG. Adaptive assignment versus balanced randomization in clinical trials: a decision analysis. Stat Med. 1995;14:231–246. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugger W, Hirsch J, Grunebach F, Repp R, Brossart P, Vogel W, Kopp HG, Manz MG, Bitzer M, Schlimok G, Kaufmann M, Ganser A, Fehnle K, Gramatzki M, Kanz L. Rituximab consolidation after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous blood stem cell transplantation in follicular and mantle cell lymphoma: a prospective, multicenter phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1691–1698. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YB, Lane AA, Logan BR, Zhu X, Akpek G, Aljurf MD, Artz AS, Bredeson CN, Cooke KR, Ho VT, Lazarus HM, Olsson RF, Saber W, McCarthy PL, Pasquini MC. Impact of conditioning regimen on outcomes for patients with lymphoma undergoing high-dose therapy with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:1046–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Shipp MA, Fisher RI, Connors JM, Lister TA, Vose J, Grillo-Lopez A, Hagenbeek A, Cabanillas F, Klippensten D, Hiddemann W, Castellino R, Harris NL, Armitage JO, Carter W, Hoppe R, Canellos GP. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump M, Kuruvilla J, Couban S, MacDonald DA, Kukreti V, Kouroukis CT, Rubinger M, Buckstein R, Imrie KR, Federico M, Di Renzo N, Howson-Jan K, Baetz T, Kaizer L, Voralia M, Olney HJ, Turner AR, Sussman J, Hay AE, Djurfeldt MS, Meyer RM, Chen BE, Shepherd LE. Randomized comparison of gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin versus dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin chemotherapy before autologous stem-cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory aggressive lymphomas: NCIC-CTG LY.12. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3490–3496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.9593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenske TS, Hari PN, Carreras J, Zhang MJ, Kamble RT, Bolwell BJ, Cairo MS, Champlin RE, Chen YB, Freytes CO, Gale RP, Hale GA, Ilhan O, Khoury HJ, Lister J, Maharaj D, Marks DI, Munker R, Pecora AL, Rowlings PA, Shea TC, Stiff P, Wiernik PH, Winter JN, Rizzo JD, van Besien K, Lazarus HM, Vose JM. Impact of pre-transplant rituximab on survival after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1455–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feugier P, Van Hoof A, Sebban C, Solal-Celigny P, Bouabdallah R, Ferme C, Christian B, Lepage E, Tilly H, Morschhauser F, Gaulard P, Salles G, Bosly A, Gisselbrecht C, Reyes F, Coiffier B. Long-term results of the R-CHOP study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a study by the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4117–4126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N, Singh Gill D, Linch DC, Trneny M, Bosly A, Ketterer N, Shpilberg O, Hagberg H, Ma D, Briere J, Moskowitz CH, Schmitz N. Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4184–4190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisselbrecht C, Schmitz N, Mounier N, Singh Gill D, Linch DC, Trneny M, Bosly A, Milpied NJ, Radford J, Ketterer N, Shpilberg O, Duhrsen U, Hagberg H, Ma DD, Viardot A, Lowenthal R, Briere J, Salles G, Moskowitz CH, Glass B. Rituximab maintenance therapy after autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with relapsed CD20(+) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: final analysis of the collaborative trial in relapsed aggressive lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4462–4469. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.9416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Campo E, Braziel RM, Jaffe ES, Pan Z, Farinha P, Smith LM, Falini B, Banham AH, Rosenwald A, Staudt LM, Connors JM, Armitage JO, Chan WC. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103:275–282. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz SM, Negrin RS, Blume KG, Breslin S, Stuart MJ, Stockerl-Goldstein KE, Johnston LJ, Wong RM, Shizuru JA, Horning SJ. Rituximab as adjuvant to high-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2004;103:777–783. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isidori A, Clissa C, Loscocco F, Guiducci B, Barulli S, Malerba L, Gabucci E, Visani G. Advancement in high dose therapy and autologous stem cell rescue in lymphoma. World J Stem Cells. 2015;7:1039–1046. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v7.i7.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamezaki K, Kikushige Y, Numata A, Miyamoto T, Takase K, Henzan H, Aoki K, Kato K, Nonami A, Kamimura T, Arima F, Takenaka K, Harada N, Fukuda T, Hayashi S, Ohno Y, Eto T, Harada M, Nagafuji K. Rituximab does not compromise the mobilization and engraftment of autologous peripheral blood stem cells in diffuse-large B-cell lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:523–527. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khouri IF, Saliba RM, Hosing C, Okoroji GJ, Acholonu S, Anderlini P, Couriel D, De Lima M, Donato ML, Fayad L, Giralt S, Jones R, Korbling M, Maadani F, Manning JT, Pro B, Shpall E, Younes A, McLaughlin P, Champlin RE. Concurrent administration of high-dose rituximab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for relapsed aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2240–2247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khouri IF, Sui D, Turturro F, Erwin WD, Bassett RL, Korbling M, Valverde R, Ahmed S, Alousi AM, Anderlini P. In-Vivo Purging with Rituximab (R) Followed By Z/BEAM Vs BEAM/R Autologous Stem Cell Conditioning for Relapsed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) Patients (pts): Mature Results from a Combined Analysis of 3 Trials. Blood. 2015;126:3192–3192. [Google Scholar]

- Kuruvilla J, MacDonald DA, Kouroukis CT, Cheung M, Olney HJ, Turner AR, Anglin P, Seftel M, Ismail WS, Luminari S, Couban S, Baetz T, Meyer RM, Hay AE, Shepherd L, Djurfeldt MS, Alamoudi S, Chen BE, Crump M. Salvage chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for transformed indolent lymphoma: a subset analysis of NCIC CTG LY12. Blood. 2015;126:733–738. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-622084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magni M, Di Nicola M, Devizzi L, Matteucci P, Lombardi F, Gandola L, Ravagnani F, Giardini R, Dastoli G, Tarella C, Pileri A, Bonadonna G, Gianni AM. Successful in vivo purging of CD34-containing peripheral blood harvests in mantle cell and indolent lymphoma: evidence for a role of both chemotherapy and rituximab infusion. Blood. 2000;96:864–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Conde E, Arnan M, Canales MA, Deben G, Sancho JM, Andreu R, Salar A, Garcia-Sanchez P, Vazquez L, Nistal S, Requena MJ, Donato EM, Gonzalez JA, Leon A, Ruiz C, Grande C, Gonzalez-Barca E, Caballero MD, Grupo Espanol de Linfomas/Trasplante Autologo de Medula, O. R-ESHAP as salvage therapy for patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the influence of prior exposure to rituximab on outcome. A GEL/TAMO study. Haematologica. 2008;93:1829–1836. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounier N, Canals C, Gisselbrecht C, Cornelissen J, Foa R, Conde E, Maertens J, Attal M, Rambaldi A, Crawley C, Luan JJ, Brune M, Wittnebel S, Cook G, van Imhoff GW, Pfreundschuh M, Sureda A, Lymphoma Working Party of European, B. & Marrow Transplantation, R. High-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in first relapse for diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: an analysis based on data from the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Registry. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:788–793. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, Somers R, Van der Lelie H, Bron D, Sonneveld P, Gisselbrecht C, Cahn JY, Harousseau JL, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1540–1545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovira J, Valera A, Colomo L, Setoain X, Rodriguez S, Martinez-Trillos A, Gine E, Dlouhy I, Magnano L, Gaya A, Martinez D, Martinez A, Campo E, Lopez-Guillermo A. Prognosis of patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma not reaching complete response or relapsing after frontline chemotherapy or immunochemotherapy. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:803–812. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2271-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarella C, Passera R, Magni M, Benedetti F, Rossi A, Gueli A, Patti C, Parvis G, Ciceri F, Gallamini A, Cortelazzo S, Zoli V, Corradini P, Carobbio A, Mule A, Bosa M, Barbui A, Di Nicola M, Sorio M, Caracciolo D, Gianni AM, Rambaldi A. Risk factors for the development of secondary malignancy after high-dose chemotherapy and autograft, with or without rituximab: a 20-year retrospective follow-up study in patients with lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:814–824. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.9777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarella C, Zanni M, Magni M, Benedetti F, Patti C, Barbui T, Pileri A, Boccadoro M, Ciceri F, Gallamini A, Cortelazzo S, Majolino I, Mirto S, Corradini P, Passera R, Pizzolo G, Gianni AM, Rambaldi A. Rituximab improves the efficacy of high-dose chemotherapy with autograft for high-risk follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a multicenter Gruppo Italiano Terapie Innnovative nei linfomi survey. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3166–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellenga E, van Putten WL, van ’t Veer MB, Zijlstra JM, Fibbe WE, van Oers MH, Verdonck LF, Wijermans PW, van Imhoff GW, Lugtenburg PJ, Huijgens PC. Rituximab improves the treatment results of DHAP-VIM-DHAP and ASCT in relapsed/progressive aggressive CD20+ NHL: a prospective randomized HOVON trial. Blood. 2008;111:537–543. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 2. Survival of patients after autologous stem cell transplantation by disease histology (n=93). (A–B) Disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) by disease histology. (C–D) DFS and OS by study arm among patients with de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Supplementary Figure 1. Survival of patients after autologous stem cell transplantation by age-group (n=93). (A–B) Disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) by age-group. (C–D) DFS and OS by study arm among patients at age 65 years or older. (E–F) DFS and OS by study arm among patients younger than 65 years old.