Abstract

Publication of a report from the Institute of Medicine in 2000 showing that a vaccine against cytomegalovirus (CMV) would likely be cost saving was very influential and encouraged the clinical evaluation of candidate vaccines. The major objective of a CMV vaccination program would be to reduce disease caused by congenital CMV infection, which is the leading viral cause of sensorineural hearing loss and neurodevelopmental delay.

CMV has challenges as a vaccine target because it is a herpesvirus, it persists lifelong despite host immunity, infected individuals can be reinfected with new strains, overt disease occurs in those with immature or impaired immune systems and persons with this infection do not usually report symptoms. Nevertheless, natural immunity against CMV provides some protection against infection and disease, natural history studies have defined the serological and molecular biological techniques needed for endpoints in future clinical trials of vaccines and CMV is not highly communicable, suggesting that it may not be necessary to achieve very high levels of population immunity through vaccination in order to affect transmission. Three phase 2 CMV vaccine studies have been completed in the last 3 years and all report encouraging outcomes.

A key international meeting was organized by the Food and Drug Administration in January 2012 at which interested parties from regulatory bodies, industry and academia discussed and prioritised designs for phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials. Vaccines able to prevent primary infection with CMV and to boost the immune response of those already infected are desirable. The major target populations for a CMV vaccine include women of childbearing age and adolescents. Toddlers represent another potential population, since an effect of vaccine in this age group could potentially decrease transmission to adults. In addition, prospective recipients of transplants and patients with AIDS would be expected to benefit.

Keywords: Vaccine, Prevention, Reinfection, Burden of disease, Hearing loss, Clinical trials

1. Epidemiology and natural history

CMV is transmitted through mucosal contact with infected body fluids, including saliva, urine, semen and cervical secretions [1–3]. After primary infection (the first infection in life), CMV establishes latency. An infected individual can experience reactivation of the latent strain or reinfection by another strain of CMV. CMV infection detected within 2 weeks of birth is termed congenital infection, and is the result of a maternal infection that first involves the placenta and then the fetus [4]. In developed countries, many women enter the childbearing years susceptible to primary infection whereas, in developing countries, virtually 100% of antenatal women are seropositive (that is, they have IgG antibodies specific for CMV antigens) [5,6]. Seropositive pregnant women can reactivate latent CMV or be reinfected with a new strain; both types of infection can transmit virus across the placenta to the developing fetus [4,7,8]. However, there is evidence that preconception maternal immunity does provide some protection against intrauterine transmission with one study showing a 69% reduction in risk for seropositive women of having a baby with congenital CMV compared to seronegative women from the same community [9].

Primary infection, reinfection and reactivation also occur in immunocompromised persons, including transplant patients. A seropositive solid organ donor can transmit CMV to cause primary infection in a seronegative recipient or reinfection in a seropositive recipient [10]. One study showed that natural immunity provides an 84% reduction in viral load parameters compared to those in seronegative recipients [11]. In haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, most infections are reactivations and seropositive donors may adoptively transfer immunity to recipients [12,13]. Adoptive transfer of CMV immunity has been achieved using isolated CMV antigen-specific T cell immunotherapy [14,15].

2. Burden of disease

CMV infection results in substantial burden of disease in congenitally infected infants and post-transplant patients. CMV is an occasional cause of heterophile negative mononucleosis in otherwise immunocompetent adults [16,17]. This virus has also been linked with other conditions, briefly mentioned below, where the associations have not been proven to be causal [18].

2.1. Congenital infection

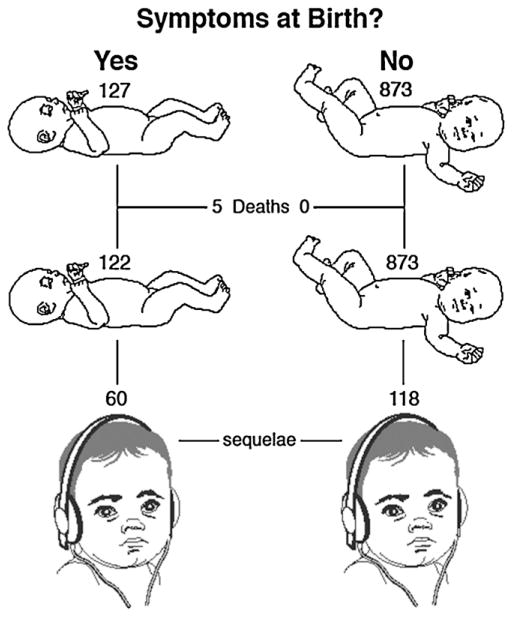

Although congenital CMV infection results in significant burden of disease globally, the best population-based estimates come from the USA. Based on reviews of the published literature, it is estimated that 0.4–0.7% of babies, (about 28,000) are born each year with congenital CMV infection in the United States; 12.7% are estimated to have symptoms at birth (termed “symptomatic”); and 13.5% of those asymptomatic at birth develop symptoms when followed-up [19,20]. The prevalence of congenital CMV infection in Europe is thought to be similar to that of the USA. Reliable data on the birth prevalence of congenital CMV infection from developing countries is lacking. In a review of studies from 11 developing countries, the average birth prevalence of congenital CMV infection was 1.6%. The classical symptoms of cytomegalic inclusion disease at birth include hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenic purpura, microcephaly and sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). The symptoms on follow-up include SNHL and/or neurodevelopmental delay [4,20]. The hearing loss is progressive (Fig. 1), so that less than half of the children destined to develop SNHL have done so by birth [21].

Fig. 1.

Disease outcome per 1000 babies with congenital CMV [20]. The major long-term effects are sensorineural hearing loss (represented by a child wearing earphones):and neurodevelopmental delay.

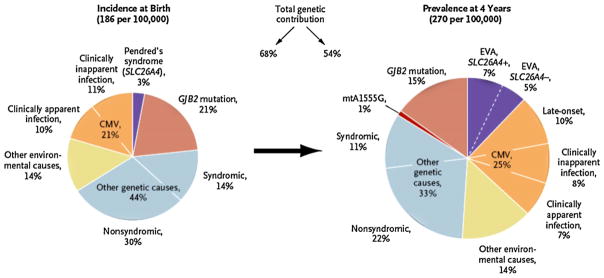

Overall, approximately 5000 babies are born in the United States each year who are estimated to develop disease caused by congenital CMV infection, making it the most common viral cause of SNHL (Fig. 2) and of neurodevelopmental delay in that country [22,23]. Congenital infection is linked to socioeconomic and racial/ethnic differences within the USA and so is linked to health disparities within a country [24].

Fig. 2.

Estimates of causes of deafness at birth and at 4 years in the USA [70]. GJB2 represents gap junction beta-2 gene, mtA1555G the mitochondrial A1555G mutation, and EVA, enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct.

It has been established that transmission and disease do occur in babies born to seropositive mothers in developing countries, but the full burden of congenital CMV in those countries remains to be defined [25]. Since the incidence of congenital infection is directly correlated with the seroprevalence of CMV antibodies in the population, congenital CMV infection may indeed exert its greatest burden in developing countries with high birth rates and high sero-prevalence.

2.2. Allografts

CMV used to be a major pathogen in transplant patients, causing pneumonitis, hepatitis, gastrointestinal ulceration, retinitis and death [26]. Nowadays, these severe forms of end organ disease (EOD) are nearly completely prevented by the routine use of preemptive therapy or prophylaxis with ganciclovir or its pro-drug valganciclovir, albeit at substantial cost. Nevertheless, late reactivation of CMV infection after the discontinuation of antiviral drugs is still a problem [27]. In addition, CMV triggers indirect effects such as graft rejection, accelerated atherosclerosis after heart or lung transplant or immunosuppression [26], the incidence of which is reduced during placebo-controlled trials of antiviral agents [28].

2.3. AIDS

The CMV-related EOD in AIDS patients is most commonly retinitis, which can largely be controlled now through the use of antiretroviral drugs [29]. However, CMV infection remains significantly associated with mortality in persons with AIDS even after controlling for CD4 count and HIV viral load [30] and an observational study reported improved survival in patients with CMV retinitis given systemic ganciclovir therapy in addition to intraocular ganciclovir [31].

2.4. Intensive care

Reactivation of CMV in patients admitted to intensive care units is associated with pneumonia, increased need for ventilation and increased mortality [32,33].

2.5. The elderly

Patients with impaired CD4/CD8 lymphocyte ratios, increased inflammation and imminent risk of death are mostly CMV seropositive, although not all seropositives have this condition [34]. It is not known whether CMV causes the deaths found in patients with such immunosenescence [35,36].

2.6. The general population

The first study to use a large systematically collected sample of a general population recently reported that the CMV seropositive state is associated with excess mortality, even after controlling for major confounders such as smoking and obesity [37]. Similar studies from outside the USA are required.

3. Pathogenesis

During primary infection, CMV disseminates in the blood and expresses its immune evasion genes to create sanctuary sites where it can persist and evade immune surveillance. If the immune system is immature (fetus) or impaired by immunosuppressive drugs or HIV infection, systemic replication levels are higher and many such sites may be established. If these are in critical locations like the cochlea, the presence of CMV progressively damages neighbouring cells, so that children with normal hearing at birth experience deterioration over months or years [21]. Quantitative studies show that CMV viraemia and a high viral load precede EOD in transplant patients [38–40].

The possession of multiple immune evasion genes gives CMV a countermeasure against many immune defence mechanisms [41,42]. CMV-encoded proteins are fully immunogenic, but immune effectors cannot identify and destroy the sanctuary sites where CMV persists, so it hides from the immune response [43]. After years of persistence, the immune response to CMV dominates the host immune repertoire in a significant proportion of the population [34,36,44]. The resulting accumulation of activated CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes could contribute to disease by either exacerbating inflammatory conditions like atherosclerosis or by compromising the ability to recruit naive cells able to respond to vaccines such as influenza [34,36,45].

An accelerated form of this CMV-associated immunosenescence appears in younger people with HIV infection where the detection of activated CD8 T lymphocytes is associated with a poor prognosis and their abundance is reduced by valganciclovir [46]. This mechanism could explain the phenomenon described as the cofactor effect of CMV, accelerating the development of AIDS and death among HIV-positive individuals who also have CMV infection [30,47]. Similar effects are seen in normal people whose immune system is stunned by a sudden massive shock to the body requiring intensive care [33].

4. Prevention

4.1. Primary prevention

Many women in developed countries are still seronegative when they reach childbearing age showing that CMV in these settings is not highly contagious [3]. The calculated basic reproductive number, representing the number of secondary infections derived from contact with one infectious case, is low at 1.7–2.5 in populations in developed countries, so that a vaccine which protects as few as 50–60% of the population could potentially lead to interruption of endemic transmission of this virus through herd immunity [24,48]. The Institute of Medicine reported in 2000 that a vaccine able to protect against CMV infection to prevent congenital CMV would be expected to be highly cost-effective [49].

A variety of strategies to developing a CMV vaccine are underway. Some of these products aim to stimulate humoral immunity, while others aim to stimulate cell mediated immunity. Only time will tell which immunogens and which arms of the adaptive immune response can provide most protection. Pioneering work with Towne vaccine in renal transplant patients provided evidence that vaccination reduced severity of EOD, but development for this indication has not continued [50]. Chimeric live virus vaccines, based on a Towne backbone but containing segments of the less-attenuated Toledo strain of CMV, have also been evaluated in phase 1 study. It is hoped that such vaccines will retain the favourable safety profile of Towne, but provide augmented immunogenicity and protection through inclusion of Toledo sequences [51]. Several other vaccine candidates are being evaluated (see Table 1), including recombinant live viruses based on Towne [52,53]. A vaccine derived from soluble glycoprotein B (gB) produced by insertion of the gene into cultured cells is currently being investigated by Sanofi Pasteur. The Sanofi Pasteur gB vaccine adjuvanted with MF59 (Novartis) has been studied in two investigator-led phase 2 double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trials [54,55] which showed that the vaccine protected approximately 50% of seronegative women from acquiring primary infection and reduced viral load parameters post-transplant in patients given vaccine before transplantation of a kidney or a liver. A different recombinant soluble gB vaccine from GlaxoSmithKline has been studied at phase 1. A DNA vaccine expressing gB and pp65 (a major target of cell mediated immunity) has completed phase 2 study, in which it reduced reactivation of CMV in hematopoietic stem cell recipients and will be developed by Astellas [56,57]. An alphavirus recombinant expressing gB, pp65 and the major immediate-early antigen will be developed by Novartis [58].

Table 1.

CMV candidate vaccines.

| Preclinical testing | Clinical testing (Phase I/II) | Efficacy trial | Outcome/perspectives | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live, attenuated (Towne) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

| Live (Towne-Toledo recombinants) | Yes | Yes | No |

|

| Recombinant gB subunit | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

| Canarypox vectors | Yes | Yes | No |

|

| MVA vectors | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Replication-defective adenovirus vectors | Yes | No | No |

|

| Alphavirus replicons | Yes | Yes | No |

|

| Peptides (combined CD4- and CD8-T cell epitopes) | Yes | Yes | No |

|

| DNA vaccines | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

|

||||

|

||||

| Dense bodies | Yes | No | No |

|

| Replication deficient whole virus vaccine | Yes | No | No |

From Ref. [69].

Although it has been demonstrated that vaccination can boost immune responses in seropositive women [59], it is currently unknown if those responses can prevent intrauterine infection through reactivation or reinfection. This is an important question as the majority of babies with congenital CMV infections in developing and developed countries are born to seropositive women, who conceivably could benefit from vaccination in the way that VZV vaccine can help to suppress reactivation of that herpesvirus.

4.2. Secondary prevention

Neonates could be screened to detect congenital CMV infection and offered interventions to compensate for damage already caused (hearing aids, speech therapy, cochlear implants) or prevent future damage [60]. CMV meets most of the major criteria for screening. At present, 27 different conditions are screened for at birth in the USA, identifying 6618 children for follow-up annually [61]. Introduction of a screening test for CMV infection would dwarf these figures by identifying 38,640 cases each year [19]. Approximately 5000 of these would be born with symptoms, making CMV a far more common condition identified than any other group of currently screened conditions [20]. When long-term follow-up is included (hence identifying congenital CMV-induced hearing loss not evident at birth), approximately 5000 children would be identified each year who would have or develop sequelae from CMV infection that might otherwise go undiagnosed [20]. Technically, congenital CMV infection could be screened for by testing the routinely collected neonatal dried blood spots for CMV DNA by PCR or by performing the same test on saliva [62,63]. Although dried blood spots are a readily available specimen, lower CMV viral loads in blood may limit their usefulness for newborn screening for CMV infection. Saliva and urine contain higher viral loads and recent results demonstrate a simplified way of processing samples to facilitate high throughput screening; however use of these specimen types would require the development of a new platform for newborn screening [63].

Passive immunisation could be used to moderate the pathogenicity of CMV in defined circumstances. A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial reported reduced CMV end organ disease in seronegative liver transplant patients with seropositive donors [64]. A nonrandomised, uncontrolled study reported reduced congenital CMV infection and disease when given to pregnant women with primary CMV infection [65]; the results of ongoing double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trials (NCT00881517, NCT01376778) are awaited.

The barriers/problems to CMV vaccine development

The fact has been established in phase 2 clinical trials that vaccines may prevent or ameliorate CMV infection in women, candidates for solid organ transplant and stem cell transplant recipients. Large phase 3 studies are now required to confirm this. Although CMV vaccine candidates up to now have concentrated on gB, the principal inducer of antibody neutralizing CMV entry into fibroblasts, and pp65, a tegument protein that is the principal inducer of CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity, it has been shown recently that entry into epithelial and endothelial cells is prevented by antibody to gB or to a pentameric complex of other proteins [66,67]. In addition, there are other targets of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes [41]. The importance of these other proteins is the subject of intensive research. Only one study has so far identified a potential correlate of protection from the vaccines under evaluation [55].

Despite these successes, there are critical gaps in our understanding of CMV epidemiology and transmission that need to be elucidated for the development of a successful CMV vaccine program. Factors that contribute to congenital CMV infection are better understood than the factors that lead to disease. The relative contributions of reinfection and reactivation during pregnancy to congenital CMV infection are poorly understood and the lack of good serological markers of non-primary infection make it challenging to investigate. Clear laboratory correlates of transmission and protection from transmission are not yet recognized. Clinical trials of promising CMV vaccine candidates can offer opportunities to better understand these issues.

How to demonstrate prevention of fetal CMV infection by CMV vaccination remains an important issue. The major targets of CMV vaccination may include not only women of reproductive age or pre-adolescent girls but also young children. The choice will depend on the properties of the vaccine, in particular duration of immunity. In addition, industry must be convinced that regulatory authorities will accept logistically and economically feasible demonstrations of efficacy against congenital CMV. For example, a primary endpoint of congenital CMV infection would allow completion of a phase 3 clinical trial with a reasonable number of subjects and within a few years. However, if prevention of congenital CMV disease is the endpoint, a much larger sample size would be required and follow-up of infected newborns to at least 2 years of age would be needed to assess the effects of the congenital infection on hearing and neurodevelopment.

It is clear that natural immunity is imperfect, largely due to the ability of CMV to evade the host immune response. It is conceivable that vaccines could improve upon natural immunity by stimulating a protective immune response without leaving the host with an immunomodulatory virus that persists indefinitely. One way to do this would be to increase population immunity to CMV to lower or interrupt transmission in a community, although this would take generations. A second way would be to use a vaccine for immunotherapy, if it could be shown that the vaccine was able to boost or rebalance the immune response made during natural infection [55,68]. A gB/MF59 vaccine has been shown to boost antibody to CMV in transplant candidates and in women [55,59]. A major barrier to evaluating protection in seropositives is the limited ability to discriminate serologically between reinfection and reactivation.

Potentially, a successful vaccine could be deployed for universal immunisation of children with the aim of increasing population immunity to eliminate this under-recognised pathogen from developed countries. If such evidence of effectiveness can be obtained, consideration could be given to interrupting CMV transmission within developing countries. The ability to protect children at an early age will be critical to achieving this in developing countries where CMV is acquired early in life. More studies to define the burden of congenital disease that results from CMV infection during pregnancies of women in developing countries are urgently needed to define the global scope of this public health problem. An analogy may exist to congenital rubella, originally thought to cause a substantial burden of disease in developed countries, but now recognized as an important cause of congenital disease wherever vaccination is not practised.

Concrete actions/recommendations

A meeting in January 2012 organised by the Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Disease Control, National Institutes of Health and National Vaccine Program Office was very influential in identifying pathways to regulatory acceptance and licensure of vaccines. A full summary of the meeting is in preparation, but our brief comments below have been informed by the multidisciplinary discussions which took place.

The encouraging results for CMV vaccines have come at a time of financial stringency. A co-ordinated, collaborative approach involving private, public and academic partners will be important to drive the CMV vaccine development forward.

Industry is planning phase 2 and phase 3 studies of vaccine candidates starting in 2012/2013. The cost of phase 3 studies is likely to be high, and support from outside of industry may be critical to ensuring these plans are implemented. Vaccine trials offer important research opportunities and should be designed to provide as much information about the epidemiology and immunology of CMV as possible. Nested studies within clinical trials of CMV vaccination of women should be conducted to determine if vaccination of toddlers can reduce transmission to their mothers and their unborn siblings. Giving vaccine to boys as well as girls, as is done for rubella, would be expected to provide better protection for pregnant women than would immunisation of girls alone.

Standardised laboratory methods for measuring viral load (using a newly produced WHO standard) and humoral and cell mediated immunity should be employed in all clinical trials to facilitate identification of correlates of protective immunity. This will be particularly important in the case of multi-antigen vaccines, because post-licensure decisions on the need for booster doses would be informed by knowledge of which immune responses were protective. Likewise, assays able to distinguish between natural immune responses and those made to any future live attenuated vaccine would be essential.

Surveillance for congenital CMV infection and disease will be critical for monitoring the effectiveness and impact of CMV vaccination. Surveillance for congenital CMV infection prior to implementation of a CMV vaccination program would be useful for establishing the baseline incidence and expanding our understanding of CMV epidemiology and disease burden. Surveillance for congenital CMV infection could be conducted through voluntary reporting to a national disease registry, inclusion in existing notifiable disease reporting systems, or through newborn screening programs. National screening bodies should be encouraged to introduce pilot sites for screening of all neonates, linked to dried blood spot screening and testing of neonates who fail screening for hearing loss. If one of these burdens was taken on by one state or country and the second by another, the results could be shared by all. By working smarter in such a way, important hurdles could be overcome cost effectively.

CMV vaccines may be given inadvertently to women who are pregnant. In addition, studies of immunotherapy may deliberately recruit pregnant women. It is difficult to contemplate vaccinating pregnant women in some countries because of the possibility that adverse pregnancy outcomes, which occur naturally, may be attributed to the vaccine and lead to litigation. This problem is shared with other vaccines and the introduction of systems such as no-fault compensation or other legislative solutions may be required.

Public health bodies should address gaps in the understanding of CMV epidemiology and transmission. In the absence of complete data, mathematical modelling of vaccines may be useful for providing examples of what reductions in congenital CMV disease burden might be expected from introduction of a CMV vaccine of defined efficacy and duration of immunity administered in different schedules and over a defined timeframe. Documentation of the duration of protection will be important for a persisting virus like CMV and will inform the need for administering booster doses of vaccine if necessary. Data from clinical trials of vaccines should be made available to refine the assumptions made in these models and so provide better predictions. Modelling may also be useful to explore the impact that CMV vaccination might have on the immune response of CMV seropositive individuals. It is also possible that a vaccine could resurrect natural immune responses that have been rendered ineffective by chronic infection or induce responses which are not produced during natural infection.

Acknowledgments

Work in the authors’ laboratories is supported by the following grants: Wellcome Trust 078332.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the initial outline of this review. The first draft was prepared by PDG. All authors critically revised this and subsequent drafts. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the paper.

Abbreviations

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- SNHL

sensorineural hearing loss

- EOD

end organ disease

- Gb

glycoprotein B

- WHO

World Health Organisation

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

EM is a paid consultant in the area of CMV vaccines for Med-Immune, LLC. All other authors declare that they have no personal conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pass RF, August AM, Dworsky M, Reynolds DW. Cytomegalovirus infection in day-care center. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(8):477–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198208193070804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pass RF, Little EA, Stagno S, Britt WJ, Alford CA. Young children as a probable source of maternal and congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(22):1366–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198705283162203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staras SA, Flanders WD, Dollard SC, Pass RF, McGowan JE, Jr, Cannon MJ. Influence of sexual activity on cytomegalovirus seroprevalence in the United States, 1988–1994. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(5):472–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181644b70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stagno S, Reynolds DW, Huang ES, Thames SD, Smith RJ, Alford CA. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 1977;296(22):1254–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197706022962203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon MJ, Schmid DS, Hyde TB. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20(4):202–13. doi: 10.1002/rmv.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffiths PD, Campbell-Benzie A, Heath RB. A prospective study of primary cytomegalovirus infection in pregnant women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87(4):308–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1980.tb04546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boppana SB, Rivera LB, Fowler KB, Mach M, Britt WJ. Intrauterine transmission of cytomegalovirus to infants of women with preconceptional immunity. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1366–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto AY, Mussi-Pinhata MM, Boppana SB, Novak Z, Wagatsuma VM, Oliveira P, et al. Human cytomegalovirus reinfection is associated with intrauterine transmission in a highly cytomegalovirus-immune maternal population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(3):297–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler KB, Stagno S, Pass RF. Maternal immunity and prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289(8):1008–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grundy JE, Lui SF, Super M, Berry NJ, Sweny P, Fernando ON, et al. Symptomatic cytomegalovirus infection in seropositive kidney recipients: reinfection with donor virus rather than reactivation of recipient virus. Lancet. 1988;2(8603):132–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90685-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emery VC, Hassan-Walker AF, Burroughs AK, Griffiths PD. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) replication dynamics in HCMV-naive and -experienced immunocompromised hosts. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(12):1723–8. doi: 10.1086/340653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grob JP, Grundy JE, Prentice HG, Griffiths PD, Hoffbrand AV, Hughes MD, et al. Immune donors can protect marrow-transplant recipients from severe cytomegalovirus infections. Lancet. 1987;1(8536):774–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92800-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wimperis JZ, Brenner MK, Prentice HG, Reittie JE, Karayiannis P, Griffiths PD, et al. Transfer of a functioning humoral immune system in transplantation of T-lymphocyte-depleted bone marrow. Lancet. 1986;1(8477):339–43. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riddell SR, Greenberg PD. T cell therapy of human CMV and EBV infection in immunocompromised hosts. Rev Med Virol. 1997;7(3):181–92. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1654(199709)7:3<181::aid-rmv200>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walter EA, Greenberg PD, Gilbert MJ, Finch RJ, Watanabe KS, Thomas ED, et al. Reconstitution of cellular immunity against cytomegalovirus in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow by transfer of T-cell clones from the donor. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(16):1038–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510193331603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen JI, Corey GR. Cytomegalovirus infection in the normal host. Medicine (Baltimore) 1985;64(2):100–14. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horwitz CA, Henle W, Henle G, Snover D, Rudnick H, Balfour HH, Jr, et al. Clinical and laboratory evaluation of cytomegalovirus-induced mononucleosis in previously healthy individuals. Report of 82 cases Medicine (Baltimore) 1986;65(2):124–34. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soderberg-Naucler C. Does cytomegalovirus play a causative role in the development of various inflammatory diseases and cancer? J Intern Med. 2006;259(3):219–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C, Zhang X, Bialek S, Cannon MJ. Attribution of congenital cytomegalovirus infection to primary versus non-primary maternal infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(2):e11–3. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dollard SC, Grosse SD, Ross DS. New estimates of the prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17(5):355–63. doi: 10.1002/rmv.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fowler KB, Dahle AJ, Boppana SB, Pass RF. Newborn hearing screening: will children with hearing loss caused by congenital cytomegalovirus infection be missed? J Pediatr. 1999;135(1):60–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cannon MJ, Davis KF. Washing our hands of the congenital cytomegalovirus disease epidemic. BMC Publ Health. 2005;5:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cannon MJ. Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) epidemiology and awareness. J Clin Virol. 2009;46(Suppl 4):S6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colugnati FA, Staras SA, Dollard SC, Cannon MJ. Incidence of cytomegalovirus infection among the general population and pregnant women in the United States. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto AY, Mussi-Pinhata MM, Isaac MD, Amaral FR, Carvalheiro CG, Aragon DC, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection as a cause of sensorineural hearing loss in a highly immune population. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:1043–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31822d9640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin RH. The indirect effects of cytomegalovirus infection on the outcome of organ transplantation. J Am Med Assoc. 1989;261(24):3607–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Limaye AP, Corey L, Koelle DM, Davis CL, Boeckh M. Emergence of ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus disease among recipients of solid-organ transplants. Lancet. 2000;356:645–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02607-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowance D, Neumayer HH, Legendre CM, Squifflet JP, Kovarik J, Brennan PJ, et al. Valacyclovir for the prevention of cytomegalovirus disease after renal transplantation. International Valacyclovir Cytomegalovirus Prophylaxis Transplantation Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(19):1462–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905133401903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jabs DA. Cytomegalovirus retinitis and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome – bench to bedside: LXVII Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(2):198–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deayton JR, Sabin CA, Johnson MA, Emery VC, Wilson P, Griffiths PD. Importance of cytomegalovirus viraemia in risk of disease progression and death in HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 2004;363(9427):2116–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16500-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kempen JH, Jabs DA, Wilson LA, Dunn JP, West SK, Tonascia J. Mortality risk for patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis and acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(10):1365–73. doi: 10.1086/379077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Limaye AP, Kirby KA, Rubenfeld GD, Leisenring WM, Bulger EM, Neff MJ, et al. Cytomegalovirus reactivation in critically ill immunocompetent patients. J Am Med Assoc. 2008;300(4):413–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Limaye AP, Boeckh M. CMV in critically ill patients: pathogen or bystander? Rev Med Virol. 2010;20(6):372–9. doi: 10.1002/rmv.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pawelec G, Derhovanessian E, Larbi A, Strindhall J, Wikby A. Cytomegalovirus and human immunosenescence. Rev Med Virol. 2009;19(1):47–56. doi: 10.1002/rmv.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Looney RJ, Falsey A, Campbell D, Torres A, Kolassa J, Brower C, et al. Role of cytomegalovirus in the T cell changes seen in elderly individuals. Clin Immunol. 1999;90(2):213–9. doi: 10.1006/clim.1998.4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derhovanessian E, Maier AB, Hahnel K, Beck R, de Craen AJ, Slagboom EP, et al. Infection with cytomegalovirus but not herpes simplex virus induces the accumulation of late-differentiated CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells in humans. J Gen Virol. 2011;92(Pt 12):2746–56. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.036004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simanek AM, Dowd JB, Pawelec G, Melzer D, Dutta A, Aiello AE. Seropositivity to cytomegalovirus, inflammation, all-cause and cardiovascular disease-related mortality in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(2):e16103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cope AV, Sweny P, Sabin C, Rees L, Griffiths PD, Emery VC. Quantity of cytomegalovirus viruria is a major risk factor for cytomegalovirus disease after renal transplantation. J Med Virol. 1997;52(2):200–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cope AV, Sabin C, Burroughs A, Rolles K, Griffiths PD, Emery VC. Interrelationships among quantity of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) DNA in blood, donor-recipient serostatus, and administration of methylprednisolone as risk factors for HCMV disease following liver transplantation. J Infect Dis. 1997;176(6):1484–90. doi: 10.1086/514145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emery VC, Sabin CA, Cope AV, Gor D, Hassan-Walker AF, Griffiths PD. Application of viral-load kinetics to identify patients who develop cytomegalovirus disease after transplantation. Lancet. 2000;355(9220):2032–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02350-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sylwester AW, Mitchell BL, Edgar JB, Taormina C, Pelte C, Ruchti F, et al. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med. 2005;202(5):673–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mocarski ES., Jr Immune escape and exploitation strategies of cytomegaloviruses: impact on and imitation of the major histocompatibility system. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6(8):707–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klenerman P, Hill A. T cells and viral persistence: lessons from diverse infections. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(9):873–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan N, Shariff N, Cobbold M, Bruton R, Ainsworth JA, Sinclair AJ, et al. Cytomegalovirus seropositivity drives the CD8T cell repertoire toward greater clonality in healthy elderly individuals. J Immunol. 2002;169(4):1984–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trzonkowski P, Mysliwska J, Szmit E, Wieckiewicz J, Lukaszuk K, Brydak LB, et al. Association between cytomegalovirus infection, enhanced proinflammatory response and low level of anti-hemagglutinins during the anti-influenza vaccination – an impact of immunosenescence. Vaccine. 2003;21(25–26):3826–36. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunt PW, Martin JN, Sinclair E, Epling L, Teague J, Jacobson MA, et al. Valganciclovir reduces T cell activation in HIV-infected individuals with incomplete CD4+ T cell recovery on antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(10):1474–83. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Webster A, Lee CA, Cook DG, Grundy JE, Emery VC, Kernoff PB, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection and progression towards AIDS in haemophiliacs with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Lancet. 1989;2(8654):63–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griffiths PD, McLean A, Emery VC. Encouraging prospects for immunisation against primary cytomegalovirus infection. Vaccine. 2001;19(11–12):1356–62. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00377-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stratton KR, Durch JS, Lawrence RS. Vaccines for the 21st century (2001) Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plotkin SA, Smiley ML, Friedman HM, Starr SE, Fleisher GR, Wlodaver C, et al. Towne-vaccine-induced prevention of cytomegalovirus disease after renal transplants. Lancet. 1984;1(8376):528–30. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90930-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heineman TC, Schleiss M, Bernstein DI, Spaete RR, Yan L, Duke G, et al. A phase 1 study of 4 live, recombinant human cytomegalovirus towne/toledo chimeric vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(10):1350–60. doi: 10.1086/503365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arvin AM, Fast P, Myers M, Plotkin S, Rabinovich R. Vaccine development to prevent cytomegalovirus disease: report from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(2):233–9. doi: 10.1086/421999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sung H, Schleiss MR. Update on the current status of cytomegalovirus vaccines. Expert Rev Vacc. 2010;9(11):1303–14. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pass RF, Zhang C, Evans A, Simpson T, Andrews W, Huang ML, et al. Vaccine prevention of maternal cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(12):1191–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Griffiths PD, Stanton A, McCarrell E, Smith C, Osman M, Harber M, et al. Cytomegalovirus glycoprotein-B vaccine with MF59 adjuvant in transplant recipients: a phase 2 randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9773):1256–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60136-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schleiss MR. VCL-CB01, an injectable bivalent plasmid DNA vaccine for potential protection against CMV disease and infection. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2009;11(5):572–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Boeckh M, Wilck MB, Langston AA, Chu AH, Wloch MK, et al. A novel therapeutic cytomegalovirus DNA vaccine in allogeneic haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:290–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bernstein DI, Reap EA, Katen K, Watson A, Smith K, Norberg P, et al. Randomized, double-blind, Phase 1 trial of an alphavirus replicon vaccine for cytomegalovirus in CMV seronegative adult volunteers. Vaccine. 2009;28(2):484–93. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sabbaj S, Pass RF, Goepfert PA, Glycoprotein Pichon S. B vaccine is capable of boosting both antibody and CD4 T-cell responses to cytomegalovirus in chronically infected women. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(11):1534–41. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dollard SC, Schleiss MR, Grosse SD. Public health and laboratory considerations regarding newborn screening for congenital cytomegalovirus. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33(Suppl 2):S249–54. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.MMWR. Impact of expanded newborn screening – United States, 2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(37):1012–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boppana SB, Ross SA, Novak Z, Shimamura M, Tolan RW, Jr, Palmer AL, et al. Dried blood spot real-time polymerase chain reaction assays to screen newborns for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;303(14):1375–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boppana SB, Ross SA, Shimamura M, Palmer AL, Ahmed A, Michaels MG, et al. Saliva polymerase-chain-reaction assay for cytomegalovirus screening in newborns. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(22):2111–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Snydman DR, Werner BG, Dougherty NN, Griffith J, Rubin RH, Dienstag JL, et al. Cytomegalovirus immune globulin prophylaxis in liver transplantation. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Boston Center for Liver Transplantation CMVIG Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:984–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-10-199311150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nigro G, Adler SP, La Torre R, Best AM. Passive immunization during pregnancy for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(13):1350–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Macagno A, Bernasconi NL, Vanzetta F, Dander E, Sarasini A, Revello MG, et al. Isolation of human monoclonal antibodies that potently neutralize human cytomegalovirus infection by targeting different epitopes on the gH/gL/UL128-131A complex. J Virol. 2010;84(2):1005–13. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01809-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Revello MG, Gerna G. Human cytomegalovirus tropism for endothelial/epithelial cells: scientific background and clinical implications. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20(3):136–55. doi: 10.1002/rmv.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, Schmader KE, Straus SE, Gelb LD, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(22):2271–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Plotkin S, Plachter B. Cytomegalovirus vaccines. In: Reddehase MJ, editor. Cytomegaloviruses: from molecular pathogenesis to therapy. Caister Academic Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morton CC, Nance WE. Newborn hearing screening – a silent revolution. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(20):2151–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]