Abstract

Background and objectives

The use of palliative care in AKI is not well described. We sought to better understand palliative care practice patterns for hospitalized patients with AKI requiring dialysis in the United States.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Using the 2012 National Inpatient Sample, we identified patients with AKI and palliative care encounters using validated International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes. We compared palliative care encounters in patients with AKI requiring dialysis, patients with AKI not requiring dialysis, and patients without AKI. We described the provision of palliative care in patients with AKI requiring dialysis and compared the frequency of palliative care encounters for patients with AKI requiring dialysis with that for patients with other illnesses with similarly poor prognoses. We used logistic regression to determine factors associated with the provision of palliative care, adjusting for demographics, hospital-level variables, and patient comorbidities.

Results

We identified 3,031,036 patients with AKI, of whom 91,850 (3%) received dialysis. We observed significant patient- and hospital-level differences in the provision of palliative care for patients with AKI requiring dialysis; adjusted odds were 26% (95% confidence interval, 12% to 38%) lower in blacks and 23% (95% confidence interval, 3% to 39%) lower in Hispanics relative to whites. Lower provision of palliative care was observed for rural and urban nonteaching hospitals relative to urban teaching hospitals, small and medium hospitals relative to large hospitals, and hospitals in the Northeast compared with the South. After adjusting for age and sex, there was low utilization of palliative care services for patients with AKI requiring dialysis (8%)—comparable with rates of utilization by patients with other illnesses with poor prognosis, including cardiogenic shock (9%), intracranial hemorrhage (10%), and acute respiratory distress syndrome (10%).

Conclusions

The provision of palliative care varied widely by patient and facility characteristics. Palliative care was infrequently used in hospitalized patients with AKI requiring dialysis, despite its poor prognosis and the regular application of life-sustaining therapy.

Keywords: acute renal failure; clinical epidemiology; United States; Comorbidity; Logistic Models; Inpatients; Shock, Cardiogenic; International Classification of Diseases; Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Adult; Palliative Care; Acute Kidney Injury; Hispanic Americans; African Continental Ancestry Group; Fluid Therapy; Intracranial Hemorrhages; Prognosis; Demography; Humans; renal dialysis

Introduction

AKI has long been recognized as a common and serious condition affecting as many as 20% of hospitalized patients (1–3), and its incidence is growing at a rate of approximately 10% per year (4–6). AKI is associated with prolonged hospital stay, costly hospitalizations, and ESRD (7,8). In-hospital mortality for patients with AKI ranges between 20% and 25% (3,9) and exceeds 50% for patients with AKI requiring dialysis (AKI-D) in a critical care unit (10).

Although dialysis may extend life in some patients with AKI, elderly hospitalized patients with AKI-D, in particular, may experience extended length of stays, greater use of life-sustaining interventions, and diminished survival compared with those initiating dialysis in the outpatient setting (11). Moreover, dialysis is associated with functional limitations, cognitive impairment, and high caregiver burden (12–16). During hospitalization, patients and their family may face tough decisions about high-risk treatments without adequate communication about prognosis or advance care planning. Even after hospitalization, survivors of AKI-D experience moderate to severe pain, anxiety, or depression and have problems with performing usual activities (17). Thus, patients with AKI-D have significant palliative care needs.

Palliative care is specialized medical care that focuses on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of a serious illness with the goal of improving the quality of life (QOL) for both the patient and the family. Studies of various conditions show that palliative care increases QOL (18), decreases symptom burden (19), improves caregiver burden (20), and associates with end of life care that is more consistent with patients’ wishes (18,21). In an intensive care unit setting, palliative care involvement has been shown to help patients cope with emotional and spiritual distress as well as increase their understanding of prognosis and goals of care (22).

The complex and unpredictable disease trajectory of patients with AKI-D—possibility of permanent dialysis dependence, impaired QOL (13), low likelihood of returning home (23), and the high mortality rate (10)—suggests that early involvement of palliative care can benefit many patients and their families (18,24). Although palliative care presence has grown dramatically in the literature for other patient populations, such as those diagnosed with cancer, heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), little is known about its use in and effect on patients with AKI-D.

We sought to better understand current palliative care practice patterns across the United States for patients with AKI-D. Our objectives were to (1) compare palliative care encounters in patients with AKI-D, patients with AKI not requiring dialysis, and patients without AKI; (2) describe the provision of palliative care in patients with AKI-D; (3) compare the frequency of palliative care encounters for patients with AKI-D with that for patients with other illnesses with poor prognoses; and (4) determine patient and hospital factors associated with palliative care encounters. We hypothesized that there would be significant variation in the provision of palliative care across patient and hospital characteristics, even after multivariable adjustment.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

We extracted data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), a nationally representative administrative database of hospitalizations in the United States created by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (25). The NIS is the largest all-payer inpatient care database and contains a 20% stratified sample of yearly discharge data from short-term, nonfederal, nonrehabilitation hospitals. Data are stratified according to geographic region, location (urban/rural), teaching status, ownership, and hospital bed number. Each hospitalization is treated as an individual entry in the database, such that individual patients who are hospitalized multiple times may be present in the NIS multiple times. Sample weights are provided to allow for the generation of national estimates along with information necessary to calculate the variance of estimates.

We used the 2012 NIS subset, the most recent year available at the time of data analysis. The 2012 NIS subset contained administrative data from over 7 million hospitalizations, representing >4000 hospitals, 44 states, and 95% of the United States population. We excluded patients under 18 years of age and patients with ESRD, who were identified using diagnosis codes and procedure codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) (Supplemental Table 1). We also excluded hospitalizations with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis or procedure code for dialysis but without a diagnosis code for AKI, assuming that these patients were treated with dialysis for ESRD. We and others have previously used this approach (5,26,27), which has been shown to produce high sensitivity and specificity as well as high positive and negative predictive values (all ≥90%) for differentiating AKI-D from maintenance dialysis (associated with ESRD) (27,28).

Definition of AKI

We identified episodes of AKI using ICD-9-CM code 584.X. This administrative code for AKI has a specificity of approximately 99% and identifies a more severe spectrum of AKI compared with AKI defined using serum creatinine criteria (27,29). For example, the median (25th–75th percentiles) change in serum creatinine from baseline is estimated at 1.2 (0.7–2.1) mg/dl compared with 0.2 (0.1–0.2) mg/dl for patients without an administrative code for AKI (27). We defined AKI-D as the presence of an AKI diagnosis code and a diagnosis or procedure code for dialysis. This algorithm for AKI-D has been shown to yield high sensitivity and specificity (27).

Covariates

Demographic variables included patient age, sex, race, health insurance status, and median household income by zip code. Hospital-level variables included geographic region, bed number, teaching status, and hospital ownership using predetermined NIS definitions (25). We assessed patient comorbidities from the 25 diagnoses listed in the NIS for each record and hospital procedures from the 15 procedures listed per record (Supplemental Table 1).

Outcome

The primary outcome was evidence of a palliative care encounter, defined by the presence of ICD-9-CM code V66.7 (encounter for palliative care). We and others have previously used this approach, which has been shown to produce a specificity of 97% and a sensitivity of 81% (30,31).

Statistical Analyses

We summarized baseline characteristics of the study participants using descriptive statistics. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as means (SEM), and non-normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as medians (25th–75th percentiles). Categorical variables were expressed as proportions. Missing data were below 5%, except for the race covariate (approximately 5% were missing). We used hot deck imputation for missing race, which replaces each missing value with a derived value from similar donor cells (32).

We used logistic regression to evaluate associations among different covariates and palliative care in patients with AKI-D, patients with AKI not requiring dialysis, and patients without AKI. These models included demographic information, hospital-level variables, patient comorbidities, and procedures listed in Table 1. We used single models for each variable to estimate the unadjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). We used backward stepwise selection to identify variables jointly associated with the provision of palliative care. Because of the small number of patients under 65 years of age on Medicare, we performed a secondary analysis in patients ages 65 years old and over that included health insurance status as a covariate (Supplemental Table 2). We compared the provision of palliative care in patients with AKI-D with that in patients with other illnesses or procedures with poor prognosis (i.e., cardiogenic shock, intracranial hemorrhage, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute leukemia, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and mechanical ventilation) adjusted for age and sex (Table 2). Finally, we compared the provision of palliative care in patients with AKI-D according to age and disease comorbidity subgroups (i.e., 80 years old or older, CKD, heart failure, COPD, cancer, cirrhosis, and mechanical ventilation) (Table 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the cohort

| Characteristicsa | No Palliative Care, 29,284,339 | Palliative Care, 484,915 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No AKI, 26,405,123 | AKI No Dialysis, 2,795,736 | AKI with Dialysis, 83,480 | No AKI, 333,095 | AKI No Dialysis, 143,450 | AKI with Dialysis, 8370 | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, yr, mean (SEM) | 56 (0.1) | 69 (0.1) | 63 (0.2) | 74 (0.2) | 75 (0.2) | 65 (0.4) |

| Sex, % | ||||||

| Men | 39 | 53 | 58 | 44 | 50 | 58 |

| Women | 61 | 47 | 42 | 56 | 50 | 42 |

| Race, % | ||||||

| White | 66 | 66 | 63 | 74 | 71 | 66 |

| Black | 13 | 17 | 16 | 9 | 12 | 12 |

| Hispanic | 10 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Native American | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Health insurance status, % | ||||||

| Medicare | 43 | 69 | 59 | 66 | 74 | 59 |

| Medicaid | 17 | 9 | 12 | 7 | 7 | 11 |

| Private | 30 | 16 | 21 | 18 | 13 | 23 |

| Self-pay | 6 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| No charge | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 4 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Median household income for patient’s zip code, % | ||||||

| Under $39,000 | 30 | 31 | 31 | 26 | 26 | 28 |

| $39,000–47,999 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 23 |

| $48,000–62,999 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 25 |

| $63,000 and over | 20 | 19 | 19 | 24 | 23 | 22 |

| Hospital-level variables | ||||||

| Hospital region, % | ||||||

| Northeast | 20 | 19 | 16 | 19 | 19 | 16 |

| Midwest | 23 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 23 |

| South | 39 | 40 | 40 | 38 | 38 | 36 |

| West | 19 | 18 | 21 | 21 | 23 | 25 |

| Hospital bed no., % | ||||||

| Small | 15 | 13 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 6 |

| Medium | 27 | 27 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 21 |

| Large | 59 | 60 | 66 | 64 | 65 | 73 |

| Hospital teaching status, % | ||||||

| Rural | 12 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| Urban nonteaching | 39 | 39 | 38 | 36 | 37 | 28 |

| Urban teaching | 49 | 51 | 57 | 54 | 56 | 69 |

| Ownership, % | ||||||

| Government nonfederal | 12 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 12 |

| Private nonprofit | 73 | 74 | 73 | 80 | 81 | 80 |

| Private investor owned | 15 | 15 | 15 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Comorbidities, % | ||||||

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 1 | 7 | 33 | 11 | 21 | 57 |

| Cancer | 9 | 12 | 14 | 43 | 32 | 24 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 0 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 11 |

| CKD | 7 | 46 | 53 | 13 | 40 | 41 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 13 | 20 | 18 | 23 | 21 | 20 |

| Cirrhosis | 1 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 16 |

| Congestive heart failure | 12 | 34 | 41 | 24 | 38 | 41 |

| Coronary artery disease | 19 | 36 | 35 | 26 | 34 | 32 |

| Dementia | 5 | 12 | 4 | 20 | 21 | 4 |

| Diabetes | 21 | 42 | 43 | 22 | 30 | 32 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 3 |

| Ischemic stroke | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 4 |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Sepsis | 3 | 17 | 39 | 14 | 37 | 60 |

| Procedures, % | ||||||

| Cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 1 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 9 |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Left ventricular assist device | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 2 | 10 | 39 | 15 | 25 | 66 |

| Operating room procedure | 31 | 17 | 27 | 10 | 13 | 28 |

The statistical significance of the differences is presented in Figure 2 and Supplemental Figures 1 and 2.

Table 2.

Provision of palliative care services according to other illnesses with poor prognosis

| Diagnosis/Procedure | No. of Patients with Diagnosis | In-Hospital Mortality, % | Patients with Evidence of a Palliative Care Encounter (Unadjusted), % | Patients with Evidence of a Palliative Care Encounter (Adjusted for Age and Sex), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKI requiring dialysis | 91,850 | 28 | 9 | 8 |

| Acute leukemia | 89,710 | 8 | 7 | 7 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 659,780 | 29 | 11 | 10 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 92,010 | 37 | 12 | 9 |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 2520 | 59 | 13 | 17 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 179,395 | 20 | 14 | 10 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 930,785 | 29 | 10 | 9 |

Table 3.

Provision of palliative care services in patients with AKI requiring dialysis according to age and disease comorbidity subgroups

| Subgroup | No. of Patients with Diagnosis | In-Hospital Mortality, % | Patients with Evidence of a Palliative Care Encounter (Unadjusted), % | Patients with Evidence of a Palliative Care Encounter (Adjusted for Age and Sex), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥80 yr | 13,750 | 32 | 11 | 10 |

| Cancer | 13,545 | 37 | 15 | 15 |

| CKD | 48,010 | 21 | 7 | 7 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 16,705 | 32 | 10 | 10 |

| Cirrhosis | 7335 | 48 | 18 | 20 |

| Congestive heart failure | 37,250 | 28 | 9 | 9 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 38,360 | 51 | 14 | 15 |

All analyses presented account for the NIS survey design (via weighting and stratification) and subpopulation measurements to generate national estimates. We created the cohort using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and conducted the analyses using StataMP, version 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

Description of Cohort

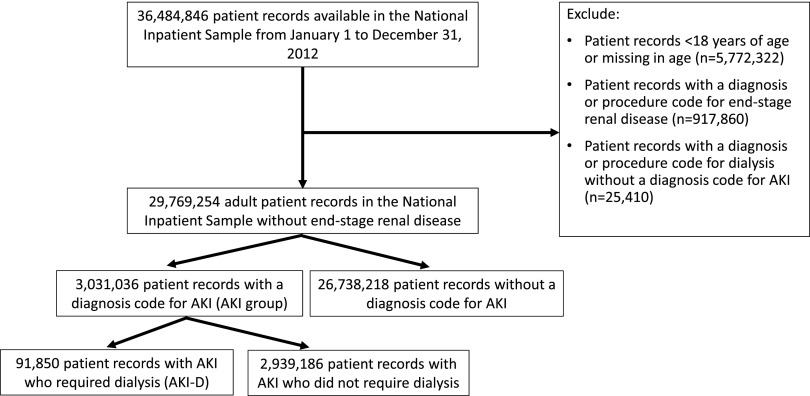

Between January 1 and December 31, 2012, there were 36,484,846 hospitalization records available in the NIS; 943,270 adult records (3%) were excluded due to ESRD or a diagnosis or procedure code for dialysis without a diagnosis code for AKI—yielding 29,769,254 (82%) records in the final cohort. Within the final cohort, 3,031,036 (10%) hospitalizations were complicated by AKI, of which 91,850 (3%) required dialysis (corresponding to 0.31% of the analytic cohort) (Figure 1). Median (interquartile range [IQR]) lengths of stay were 5 (IQR, 3–9) days for patients with AKI and 12 (IQR, 6–20) days for patients with AKI-D.

Figure 1.

Cohort of patients with and without AKI identified for the study using the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Among the entire cohort, there was evidence of a palliative care encounter for 484,915 (2%) patients. Only 8370 (9%) of 91,850 patients with AKI-D had evidence of a palliative care encounter compared with 143,450 (5%) of 2,939,186 patients with AKI not requiring dialysis.

Table 1 illustrates the baseline characteristics of the cohort stratified by the provision of palliative care. Patients with AKI-D who had evidence of a palliative care encounter were more likely to be older and white compared with patients without evidence of a palliative care encounter. Provision of palliative care was more common in Medicare and privately insured patients with AKI-D. Patients with AKI-D and incomes below $48,000 were less likely to have evidence of a palliative care encounter, whereas those with incomes $48,000 and above were more likely to have evidence of a palliative care encounter. The Northeast and South regions were less likely to provide palliative care services, whereas the Midwest and West regions were more likely to provide palliative care services. Patients with AKI-D who were hospitalized in large urban teaching hospitals were more likely to have encounters for palliative care. Private nonprofit-owned hospitals were more likely to provide palliative care services, and private investor–owned hospitals were less likely to provide such services.

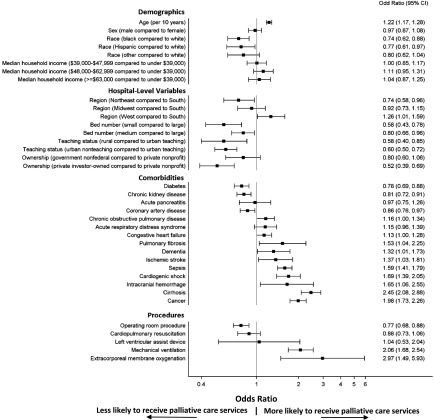

Characteristics Associated with the Provision of Palliative Care

Figure 2 illustrates the associations between patient- and hospital-level characteristics (Table 1) identified in the multivariable model for the provision of palliative care among patients with AKI-D. Results for patients without AKI and patients with AKI not requiring dialysis were similar (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2.

Multiple factors are associated with the provision of palliative care in patients with AKI requiring dialysis. Factors included in the figure were identified via backward stepwise selection from the characteristics shown in Table 1. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) reflecting the magnitudes of these associations are shown; 95% CIs that do not cross one denote statistical significance.

Demographics.

Older age was associated with a higher likelihood of palliative care (OR, 1.22 per 10 years; 95% CI, 1.17 to 1.28). The odds of provision of palliative care were 26% (95% CI, 12% to 38%) lower in blacks and 23% (95% CI, 3% to 39%) lower in Hispanics relative to whites.

When the analysis was restricted to patients with AKI-D ages 65 years old and over, private insurance and self-pay/other insurance were not associated with greater provision of palliative care relative to that for patients with AKI-D on Medicare. Including health insurance status in our other models (no AKI and AKI no dialysis) produced opposite results to the main analysis—private insurance and self-pay/other insurance were associated with greater provision of palliative care relative to that for patients with no AKI and patients with AKI not on dialysis on Medicare (Supplemental Table 2).

Hospital-Level Variables.

A number of hospital factors were associated with lower odds of a palliative care encounter. Compared with large hospitals, patients with AKI-D in small and medium hospitals were less likely to receive palliative care services (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.43 to 0.78 and OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66 to 0.96, respectively). Lower provision of palliative care services was also observed for rural (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.85) and urban nonteaching (OR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.50 to 0.72) hospitals relative to urban teaching hospitals and private investor–owned hospitals relative to private nonprofit hospitals (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.39 to 0.69). Compared with hospitals located in the South region, hospitals in the Northeast (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.58 to 0.96) had lower odds of a palliative care encounter, whereas hospitals in the West (OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.59) had higher odds of a palliative care encounter.

Comorbidities and Procedures.

Most patient comorbidities and hospital procedures were associated with a higher likelihood of an encounter for palliative care. We observed the strongest associations with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (OR, 2.97; 95% CI, 1.49 to 5.93) followed by cirrhosis (OR, 2.45; 95% CI, 2.08 to 2.88), mechanical ventilation (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.68 to 2.54), cancer (OR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.73 to 2.26), cardiogenic shock (OR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.39 to 2.05), intracranial hemorrhage (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.06 to 2.55), sepsis (OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.41 to 1.79), and pulmonary fibrosis (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.04 to 2.25).

The presence of coronary artery disease (OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76 to 0.97), CKD (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.72 to 0.91), and diabetes (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.69 to 0.88) were associated with a lower likelihood of palliative care, as was an operating room procedure performed during the hospitalization (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.68 to 0.88).

Palliative Care Encounters Stratified by Other Illnesses with Poor Prognosis

When AKI-D was compared with other illnesses with poor prognosis, encounters for palliative care were comparable with most other conditions (Table 2). Only 8% of patients with AKI-D (adjusted for age and sex) had evidence of a palliative care encounter. Other serious illnesses or procedures in which similar proportions of patients had evidence of a palliative care encounter included intracranial hemorrhage (10%), acute respiratory distress syndrome (10%), cardiogenic shock (9%), and mechanical ventilation (9%).

Palliative Care Encounters Stratified by Age and Disease Subgroups

When we compared the rates of palliative care use across the subgroups of patients with AKI-D (adjusted for age and sex), encounters for palliative care were highest for patients with cirrhosis (20%) followed by cancer (15%), mechanical ventilation (15%), age 80 years old or older (10%), COPD (10%), heart failure (9%), and CKD (7%) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study of a contemporary, nationally representative cohort of hospitalized patients from across the United States found that fewer than one in ten patients with AKI-D receive palliative care services during their hospital stay. The provision of palliative care in patients with AKI-D was low and comparable with that of patients with other illnesses with poor prognosis. Moreover, we observed significant variation in palliative care encounters according to patient demographics, hospital-level variables, and patient comorbidities. These findings suggest that palliative care may be inconsistently applied in patients with AKI-D, with opportunities available to expand and enhance its use.

Despite numerous benefits of palliative care, we are aware of only one small study that examined the provision of palliative care in the setting of AKI. In their retrospective analysis at a single center, Okon et al. (33) identified 230 patients with AKI who required continuous RRT over a 7-year period from 1999 to 2006. Although this tertiary center had a dedicated palliative care program that was available around the clock, only 55 (24%) of 230 patients received palliative care.

In addition to providing more representative data on palliative care encounters for patients with AKI-D in the United States, we found large demographic disparities in its application. Despite generally similar rates of AKI and associated complications (3,7), the odds of palliative care varied by race/ethnicity, with 26% lower odds in blacks and 23% lower odds in Hispanics relative to non-Hispanic whites. These racial/ethnic differences in the provision of palliative care persisted, even after accounting for age, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, hospital characteristics, and regional differences in practice. Additional efforts are needed to systematically engage patients of different races and cultures to improve end of life care.

Not surprisingly, palliative care services were less commonly provided in smaller and rural hospitals. Effective palliative care programs require a well trained workforce, multidisciplinary teamwork, and sufficient financial resources (34). The absence of these supporting factors in small and rural centers may explain the lower provision of palliative care. Larger urban teaching hospitals represented approximately 50% of the centers in our cohort, and therefore, uncovering reasons for these hospital-level differences offers a valuable opportunity to expand palliative care services in AKI-D.

Although palliative care encounters for patients with AKI-D (8%) were relatively low, they were comparable with those for patients with other illnesses with poor prognosis, such as cardiogenic shock (9%), acute respiratory distress syndrome (10%), and intracranial hemorrhage (10%) (Table 2). Hence, palliative care seems to be infrequently used across most conditions, and AKI-D is no exception. Even subgroups of patients with AKI-D who may benefit the most from palliative care have evidence of low palliative care encounters, such as patients who are 80 years old or older (10%) and patients with comorbidities, such as CKD (7%), heart failure (9%), COPD (10%), cancer (15%), and cirrhosis (20%) (Table 3). These infrequent uses of palliative care raise the possibility of missed opportunities when palliative care might have facilitated timely shared decision making to improve patient-centered care. Needless to say, decisions not to involve palliative care may be appropriate (e.g., a patient with AKI-D who has a reasonable expectation to survive to hospital discharge with minimal functional limitations) (35).

Although we cannot determine the appropriate use of palliative care due to the limitations of the NIS dataset, our findings can inform the direction of future studies. To address the variation and lack of use of palliative care services for patients with AKI-D that we observed, future research should focus on the clinical scenarios in which palliative care is most appropriate and beneficial for patients with AKI-D (e.g., further research examining and validating prognostic models to more accurately predict outcomes for patients with AKI-D or at risk for AKI-D, so that goals of care conversations can potentially start in an outpatient setting [36–38]).

In addition, quality of end of life care for patients with AKI-D should also be compared with that of other patients with palliative care needs. For example, Wong et al. (11) showed higher intensity of care (e.g., high rates of hospitalization, critical care admission, and use of intensive procedures) during the final month of life for patients with ESRD compared with those with cancer and heart failure. Similarly, Wachterman et al. (39) showed that patients with ESRD were less likely to have received a palliative care consultation, more likely to have died in a critical care setting, and more likely to receive unfavorable family responses compared with patients with cancer and dementia (39).

Furthermore, educational tools, such as a required palliative care rotation, increased didactics, and/or grand rounds dedicated to topics in palliative and end of life care in nephrology, should be used to promote the integration of palliative care skills into practice (40). These programs and clinical practice guidelines will be needed to standardize the provision of palliative care in patients with AKI-D, such as has been started for patients with ESRD (41,42). With the anticipated shortage of palliative care specialists, nephrologists may need to expand their clinical repertoire to include a stronger knowledge base in primary palliative care (43,44).

Most importantly, preparedness planning (45) and knowledge translation are essential, so that health care providers and caregivers recognize that early involvement of palliative care provides the needed support for the patient and their family throughout the illness as well as smooth transitions to comfort care, even if the patient recovers from AKI-D (46). Post recovery, palliative care can manage symptoms and support patients and families as well as assist with timely advance care planning to outline future care goals. If the patient’s condition declines, palliative care can assist with end of life preparation, symptom management, and bereavement support (47).

Strengths of this study include the use of a nationally representative database, which included a broad cross-section of hospitals. As a result, our findings represent contemporary provision of palliative care services for patients with AKI-D across the United States. Access to NIS data on patient, hospital-level, and regional variables allowed us to identify factors associated with low utilization of palliative care, which could serve as a basis for educational and quality improvement initiatives.

Our study has important limitations. First, we used administrative codes to identify patients with AKI and AKI-D. Although these codes are specific, particularly for AKI-D, they are more likely to identify episodes of moderate to severe AKI compared with mild AKI (27,29). Second, we identified palliative care services using an administrative code. Although also specific for a palliative care encounter (30), this code lacks granularity in that it does not identify the indication for palliative care (i.e., counseling, symptom control, or goals of care) or the mode of delivery (30). Thus, our analysis may include any palliative care encounter with or without consultation by a specialized palliative care service (30). Moreover, some of the observed geographic and hospital-level variation could relate to differential coding practices rather than differences in the provision of palliative care. Third, the NIS lacks information on the sequence of events during a hospitalization. As a result, we could not determine the timing of palliative care services relative to procedures or other events, which prevented us from estimating the effect that palliative care might have on mortality, procedure use, provision or duration of intensive care, length of stay, and discharge to home or skilled nursing facility. Fourth, despite our efforts, residual confounding is likely, especially because administrative data limit our ability to capture the severity of comorbid conditions. For example, the NIS does not capture admission to an intensive care unit, which could provide information on the severity of illness. Fifth, we were not able to determine the reasons underlying the differential provision of palliative care or whether provision/nonprovision of palliative care was appropriate, which is an area primed for further research.

In conclusion, we found that fewer than one in ten hospitalized patients with AKI-D received palliative care services in the United States. We observed significant variation in the provision of palliative care by race/ethnicity, region, hospital characteristics, and preexisting comorbidity. We also found that low utilization of palliative care services in patients with AKI-D was comparable with that of patients with other illnesses with poor prognosis. These findings suggest that palliative care may be an infrequently used clinical service for patients with AKI-D, and several opportunities exist to expand and enhance its use.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

S.A.S. is supported by a Kidney Research Scientist Core Education and National Training Program Post-Doctoral Fellowship (cofunded by the Kidney Foundation of Canada, the Canadian Society of Nephrology, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research). G.M.C. was supported by a K24 midcareer mentoring award from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant K24 DK085446.

These funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Recognizing the Elephant in the Room: Palliative Care Needs in Acute Kidney Injury,” on pages 1721–1722.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.00270117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM: Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 844–861, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng X, McMahon GM, Brunelli SM, Bates DW, Waikar SS: Incidence, outcomes, and comparisons across definitions of AKI in hospitalized individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 12–20, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Susantitaphong P, Cruz DN, Cerda J, Abulfaraj M, Alqahtani F, Koulouridis I, Jaber BL; Acute Kidney Injury Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology : World incidence of AKI: A meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1482–1493, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siew ED, Himmelfarb J: The inexorable rise of AKI: Can we bend the growth curve? J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 3–5, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, Lo LJ, Hsu CY: Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 37–42, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue JL, Daniels F, Star RA, Kimmel PL, Eggers PW, Molitoris BA, Himmelfarb J, Collins AJ: Incidence and mortality of acute renal failure in Medicare beneficiaries, 1992 to 2001. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1135–1142, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW: Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3365–3370, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR: Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int 81: 442–448, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selby NM, Kolhe NV, McIntyre CW, Monaghan J, Lawson N, Elliott D, Packington R, Fluck RJ: Defining the cause of death in hospitalised patients with acute kidney injury. PLoS One 7: e48580, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchino S, Bellomo R, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Macedo E, Gibney N, Tolwani A, Oudemans-van Straaten H, Ronco C, Kellum JA: Continuous renal replacement therapy: A worldwide practice survey. The beginning and ending supportive therapy for the kidney (B.E.S.T. kidney) investigators. Intensive Care Med 33: 1563–1570, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE: Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 361: 1539–1547, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansen KL, Smith MW, Unruh ML, Siroka AM, O’Connor TZ, Palevsky PM; VA/NIH Acute Renal Failure Trial Network : Predictors of health utility among 60-day survivors of acute kidney injury in the Veterans Affairs/National Institutes of Health Acute Renal Failure Trial Network Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1366–1372, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray AM, Tupper DE, Knopman DS, Gilbertson DT, Pederson SL, Li S, Smith GE, Hochhalter AK, Collins AJ, Kane RL: Cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients is common. Neurology 67: 216–223, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suri RS, Larive B, Hall Y, Kimmel PL, Kliger AS, Levin N, Tamura MK, Chertow GM; Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) Trial Group : Effects of frequent hemodialysis on perceived caregiver burden in the Frequent Hemodialysis Network trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 936–942, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mashayekhi F, Pilevarzadeh M, Rafati F: The assessment of caregiver burden in caregivers of hemodialysis patients. Mater Sociomed 27: 333–336, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahlström A, Tallgren M, Peltonen S, Räsänen P, Pettilä V: Survival and quality of life of patients requiring acute renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med 31: 1222–1228, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ: Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363: 733–742, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, McPhee SJ: The comprehensive care team: A controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med 164: 83–91, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Fazekas BS, Luszcz MA, Wheeler JL, Kuchibhatla M: Specialized palliative care services are associated with improved short- and long-term caregiver outcomes. Support Care Cancer 16: 585–597, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, Mitchell SL, Jackson VA, Block SD, Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG: Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 300: 1665–1673, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machare Delgado E, Callahan A, Paganelli G, Reville B, Parks SM, Marik PE: Multidisciplinary family meetings in the ICU facilitate end-of-life decision making. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 26: 295–302, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thakar CV, Quate-Operacz M, Leonard AC, Eckman MH: Outcomes of hemodialysis patients in a long-term care hospital setting: A single-center study. Am J Kidney Dis 55: 300–306, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chertow GM, Christiansen CL, Cleary PD, Munro C, Lazarus JM: Prognostic stratification in critically ill patients with acute renal failure requiring dialysis. Arch Intern Med 155: 1505–1511, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP): HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed January 10, 2016

- 26.Lenihan CR, Montez-Rath ME, Mora Mangano CT, Chertow GM, Winkelmayer WC: Trends in acute kidney injury, associated use of dialysis, and mortality after cardiac surgery, 1999 to 2008. Ann Thorac Surg 95: 20–28, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waikar SS, Wald R, Chertow GM, Curhan GC, Winkelmayer WC, Liangos O, Sosa MA, Jaber BL: Validity of international classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification codes for acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1688–1694, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vlasschaert ME, Bejaimal SA, Hackam DG, Quinn R, Cuerden MS, Oliver MJ, Iansavichus A, Sultan N, Mills A, Garg AX: Validity of administrative database coding for kidney disease: A systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 57: 29–43, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grams ME, Waikar SS, MacMahon B, Whelton S, Ballew SH, Coresh J: Performance and limitations of administrative data in the identification of AKI. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 682–689, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murthy SB, Moradiya Y, Hanley DF, Ziai WC: Palliative care utilization in nontraumatic intracerebral hemorrhage in the United States. Crit Care Med 44: 575–582, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qureshi AI, Adil MM, Suri MF: Rate of utilization and determinants of withdrawal of care in acute ischemic stroke treated with thrombolytics in USA. Med Care 51: 1094–1100, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andridge RR, Little RJ: A review of hot deck imputation for survey non-response. Int Stat Rev 78: 40–64, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okon TR, Vats HS, Dart RA: Palliative medicine referral in patients undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury. Ren Fail 33: 707–717, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamura MK, Meier DE: Five policies to promote palliative care for patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1783–1790, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akbar S, Moss AH: The ethics of offering dialysis for AKI to the older patient: Time to re-evaluate? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1652–1656, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Demirjian S, Chertow GM, Zhang JH, O’Connor TZ, Vitale J, Paganini EP, Palevsky PM; VA/NIH Acute Renal Failure Trial Network : Model to predict mortality in critically ill adults with acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 2114–2120, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saly D, Yang A, Triebwasser C, Oh J, Sun Q, Testani J, Parikh CR, Bia J, Biswas A, Stetson C, Chaisanguanthum K, Wilson FP: Approaches to predicting outcomes in patients with acute kidney injury. PLoS One 12: e0169305, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang CH, Fan PC, Chang MY, Tian YC, Hung CC, Fang JT, Yang CW, Chen YC: Acute kidney injury enhances outcome prediction ability of sequential organ failure assessment score in critically ill patients. PLoS One 9: e109649, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL: Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med 176: 1095–1102, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Combs SA, Culp S, Matlock DD, Kutner JS, Holley JL, Moss AH: Update on end-of-life care training during nephrology fellowship: A cross-sectional national survey of fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 233–239, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grubbs V, Moss AH, Cohen LM, Fischer MJ, Germain MJ, Jassal SV, Perl J, Weiner DE, Mehrotra R; Dialysis Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology : A palliative approach to dialysis care: A patient-centered transition to the end of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2203–2209, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Renal Physicians Association: Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis, 2nd Ed., Rockville, MD, Renal Physicians Association, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lupu D; American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force : Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage 40: 899–911, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quill TE, Abernethy AP: Generalist plus specialist palliative care--Creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 368: 1173–1175, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swetz KM, Ottenberg AL, Freeman MR, Mueller PS: Palliative care and end-of-life issues in patients treated with left ventricular assist devices as destination therapy. Curr Heart Fail Rep 8: 212–218, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Mahony S, McHenry J, Blank AE, Snow D, Eti Karakas S, Santoro G, Selwyn P, Kvetan V: Preliminary report of the integration of a palliative care team into an intensive care unit. Palliat Med 24: 154–165, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scherer JS, Holley JL: The role of time-limited trials in dialysis decision making in critically ill patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 344–353, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.