Abstract

Background:

Plecanatide, with the exception of a single amino acid replacement, is identical to human uroguanylin and is approved in the United States for adults with chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC). This double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study evaluated the efficacy and safety of plecanatide versus placebo in CIC.

Methods:

Adults meeting modified Rome III CIC criteria were randomized to plecanatide 3 mg (n = 443), 6 mg (n = 449), or placebo (n = 445). Patients recorded bowel movement (BM) characteristics [including spontaneous BMs (SBMs) and complete SBMs (CSBMs)] and rated CIC symptoms in daily electronic diaries. The primary endpoint was the percentage of durable overall CSBM responders (weekly responders for ⩾9 of 12 treatment weeks, including ⩾3 of the last 4 weeks). Weekly responders had ⩾3 CSBMs/week and an increase of ⩾1 CSBM from baseline for the same week.

Results:

A significantly greater percentage of durable overall CSBM responders resulted with each plecanatide dose compared with placebo (3 mg = 20.1%; 6 mg = 20.0%; placebo = 12.8%; p = 0.004 each dose). Over the 12 weeks, plecanatide significantly improved stool consistency and stool frequency. Significant increases in mean weekly SBMs and CSBMs began in week 1 and were maintained through week 12 in plecanatide-treated patients. Adverse events were mostly mild/moderate, with diarrhea being the most common (3 mg = 3.2%; 6 mg = 4.5%; placebo = 1.3%).

Conclusions:

Plecanatide resulted in a significantly greater percentage of durable overall CSBM responders and improved stool frequency and secondary endpoints. Plecanatide was well tolerated; the most common AE, diarrhea, occurred in a small number of patients.

[ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02122471]

Keywords: complete spontaneous bowel movement, durable overall CSBM responder, guanylate cyclase-C, uroguanylin

Introduction

Chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) is a common, symptom-based gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by infrequent stools, difficult stool passage, or both.1–3 Difficult stool passage includes straining, the sensation of incomplete bowel movements (BMs; incomplete evacuation), hard/lumpy stools, or the need for manual removal of stool. CIC can be accompanied by abdominal symptoms such as bloating and discomfort, with these symptoms often adversely affecting patients’ quality of life.

In the United States (US), CIC affects an estimated 35 million individuals, with prevalence rates ranging from 2% to 27%, averaging 14% of the general population.3 Although it is thought that the prevalence of constipation increases with age, the data are quite variable. Women are more than twice as likely to have CIC than are men,3 and a recent US survey found that 62% of respondents with CIC were <50 years of age.2 CIC is costly to patients and payers.4 Compared with matched controls, US patients with CIC incur an estimated US$2840 more in medical costs and US$668 more in prescription costs each year (in 2010 dollars). The additional economic burden for patients with abdominal symptoms is even greater, with estimated annual incremental medical and prescription costs of US$3761 and US$685, respectively.4

Due to the critical role it plays in the maintenance of intestinal fluid and electrolyte homeostasis, the guanylate cyclase-C (GC-C) receptor has recently emerged as a promising target for treating CIC.5 The activation of the GC-C receptor by uroguanylin, a pH-sensitive endogenous ligand, stimulates cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) production. This results in increased cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activity,6 which in turn stimulates chloride and bicarbonate secretion into the intestinal lumen. Increased cGMP also decreases the activity of the sodium-hydrogen exchanger, leading to decreased sodium absorption. The result is an ionic gradient that allows for fluid secretion that serves to hydrate the stool and facilitate BMs.7,8

There are currently two GC-C agonists available in the United States for the treatment of adults with CIC. Linaclotide is a 14-amino acid peptide that contains three disulfide bonds and acts in a pH-independent manner to stimulate fluid secretion into the intestinal lumen. In contrast, plecanatide is a 16-amino acid peptide with two disulfide bonds that is thought to replicate the activity of human uroguanylin and similarly binds to and activates GC-C receptors in a pH-sensitive manner.9 Plecanatide differs from uroguanylin by the replacement of aspartic acid with glutamic acid at the third position near the N-terminus.9 In preclinical models, plecanatide has demonstrated potency eight times that of uroguanylin.10 In healthy adults11 and in patients with CIC,12,13 plecanatide was generally safe and well tolerated, with no evidence of systemic absorption with clinically relevant doses. Clinical efficacy and safety were previously shown in a phase III study [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01982240],14 which utilized a similar clinical trial design to the current study. In that first phase III trial,14 treatment with plecanatide resulted in a statistically significantly greater percentage of durable overall complete spontaneous bowel movement (CSBM) responders versus placebo (plecanatide 3 mg = 21.0%; plecanatide 6 mg = 19.5%; placebo = 10.2%; p < 0.001 for both doses).

The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of once-daily oral plecanatide tablets (3 mg and 6 mg) compared with placebo over 12 weeks of treatment in patients with CIC, using the percentage of patients achieving durable overall CSBM response as the primary endpoint.

Materials and methods

Study design

In this 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase III clinical study, patients with CIC (n = 1410) were randomized at 162 clinical centers in the US over an 8-month period starting on 16 May 2014 and ending on 28 January 2015. The last patient visit occurred on 13 May 2015. Each patient provided informed consent prior to admission into the study and initiation of any study-related procedures, in accordance with regulatory and legal requirements. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02122471]. Approval for this study was obtained from Copernicus Group, a centralized independent review board (IRB), and an IRB from one local site (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center IRB), and the study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization E6 Consolidated Guidance for Good Clinical Practice, the United States Code of Federal Regulations 21 (parts 50 and 56), and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Following completion of informed consent, patients were required to enter a screening period. The last 2 weeks of the screening period were used to confirm eligibility and to establish individual patient baseline values for efficacy endpoints. Patients were instructed to use an electronic diary to maintain a daily BM Diary (number of BMs, time of BM, rescue medication use, stool consistency, and completeness of evacuation) and a daily Symptom Diary for grading of GI symptoms (straining, abdominal bloating, and abdominal discomfort). Recordings were required on at least a daily basis, with no means to complete data for previous days in order to reduce reliance on memory. To maintain eligibility for participation in the trial, patients were required to complete six of the seven daily electronic diary entries (among other criteria) in both pretreatment assessment weeks.

Patients who maintained their clinical trial eligibility at the end of the 2-week pretreatment period were randomized 1:1:1 (stratified by gender) on day 1 of the 12-week treatment period to plecanatide 3 mg, plecanatide 6 mg, or placebo using a web-based randomization and study supply management system (Interactive Web Response System [IWRS]; Sharp Clinical Services, Phoenixville, PA, USA). Patients were instructed to return to the clinic to undergo efficacy and safety evaluations at weeks 4, 8, and 12 of the treatment period, as well as 2 weeks following their last dose of medication (week 14). Patients were required to continue their use of the electronic diary throughout the treatment and post-treatment follow-up periods.

Patients

Male and female patients aged 18–80 years (inclusive) and with a body mass index of 18–40 kg/m2 (inclusive) were eligible for inclusion in this study if they met the following modified Rome III functional constipation criteria for at least 3 months before the screening visit with symptom onset at least 6 months before the diagnosis. The Rome III criteria, as modified for this study, required the following:

Patient reported that loose stools were rarely present without the use of laxatives

Patient did not meet the Rome III criteria for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation

Patient did not use manual maneuvers (e.g. digital evacuation, support of the pelvic floor) to facilitate defecations

Patient reported a history of less than three defecations per week

- Patient reported at least two of the following:

- Straining during ⩾25% of defecations

- Lumpy or hard stool in ⩾25% of defecations

- Sensation of incomplete evacuation for ⩾25% of defecations

- Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage for ⩾25% of defecations (with no anatomic obstruction found)

Patients who met the modified Rome III criteria for functional constipation based on history also had to demonstrate the following during the pretreatment assessment period: fewer than three CSBMs each week and a Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS)15 score of 6 or 7 in <25% of spontaneous bowel movements (SBMs). In addition, patients also had to demonstrate one of the following three measures: BSFS score of 1 or 2 in ⩾25% of defecations, a straining value recorded on ⩾25% of days when a BM was reported, or ⩾25% of BMs resulted in a sense of incomplete evacuation. Patients were required to maintain a stable diet (which could have included a high-fiber diet, fiber supplements, vitamins and minerals, probiotics or fish oil) for ⩾30 days prior to screening and during the study, to use adequate contraception where applicable, and were not to have participated in a previous plecanatide clinical study.

The key exclusion criteria included: presence or history of diseases or conditions that were associated with constipation (e.g. originating from the GI system, central nervous system or collagen vascular disease), structural or postsurgical GI disorders, diseases or conditions that could affect GI motility or defecation, medical history of cancer in the past 5 years (other than basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma of the skin), or presence of any other uncontrolled medical conditions. Prohibited laxatives included lactulose, stimulant laxatives, osmotic laxatives, stool softeners, lubiprostone, linaclotide, and prucalopride.

Randomization and masking

Investigators randomized patients (1:1:1) in a double-blind manner to receive a once-daily oral dose of plecanatide 3 mg, plecanatide 6 mg, or placebo. An IWRS was used for patient randomization in this study that maintained concealment of treatment assignment. Randomization to treatment group was performed centrally using a standard nine-patient block size and stratified by gender to evenly distribute male patients. All study drugs were supplied in identical blister packs, and tablets were similar in smell, taste, and appearance, thereby assuring double-blind conditions for all investigators, study personnel and patients. In the event of an emergency, the clinical investigator could break the treatment code using the IWRS; however, no break of the treatment code occurred in this study.

Procedures

Patients were randomized to receive a once-daily oral dose of plecanatide 3 mg, plecanatide 6 mg, or placebo for 12 weeks. Patients received their assigned study drug on the day of clinical trial enrollment (day 1, week 1). Patients were required to take their first dose at the clinic site and were instructed to take study medication thereafter once daily in the morning, with or without food. Patients returned to the clinic to undergo efficacy and safety assessments at weeks 4, 8, and 12, and at a follow-up visit 2 weeks after the end of treatment (week 14). The investigator or designated site personnel performed drug-dispensing activities at day 1, week 4, and week 8 visits by logging into the IWRS to obtain a study drug kit allocation for each patient, with each dispensed kit recorded in the electronic data capture system. Compliance to treatment was assessed by pill count, with patients who had taken at least 80% of their assigned doses over the 12-week treatment period considered compliant. No interruptions in daily therapy were permitted. Patients were permitted to use provided rescue medication (bisacodyl 5 mg tablets) only if they had not had a BM in the past 72 h; use of rescue medication was recorded in the BM Diary to determine BM spontaneity.

Outcomes

Efficacy

The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage of patients who were durable overall CSBM responders. A CSBM was defined as an SBM (occurring in the absence of laxative use within 24 h of the BM), with the patient also reporting a sense of complete evacuation. A CSBM weekly responder was defined as a patient who experienced ⩾3 CSBMs in a given week and an increase of ⩾1 CSBM (compared with their baseline) in that same week. A durable overall CSBM responder was defined as a weekly responder for ⩾9 of the 12 treatment weeks, including ⩾3 of the final 4 weeks of treatment. Secondary endpoints included the change from baseline over the 12-week treatment period in mean weekly CSBM frequency, mean weekly SBM frequency, and mean stool consistency (BSFS score), as well as the change from baseline in mean straining, constipation severity, and abdominal symptom scores. Other endpoints included the Patient Assessment of Constipation–Symptoms (PAC-SYM), Patient Assessment of Constipation–Quality of Life (PAC-QOL), and Patient Global Assessment (PGA) questionnaire scores and the calculated percentage of patients who experienced a CSBM or SBM within 24 h after the first dose of study medication.

The electronic diary used during the screening assessment period was used to complete the daily BM Diary [number of BMs, time, rescue medication use, stool consistency (using the BSFS), completeness of evacuation] and the daily Symptom Diary (straining, abdominal bloating, abdominal discomfort: at its worst on a Likert scale of 0–4, where 0 = none, 4 = very severe) throughout the treatment and post-treatment follow-up periods. Data for the BM Diary could be entered in real time or at the end of the day; Symptom Diary entries were made at the end of each day. As during the diary assessment in the screening/pretreatment period, there was no option for entering data from previous days.

Safety and tolerability

Safety evaluations were conducted at each study visit, including physical examinations, vital sign measurements, and standard laboratory tests. An electrocardiogram was completed at the start of screening and at weeks 1 and 12. Adverse events (AEs) were derived by spontaneous, unsolicited reports of patients, by observation, and by routine open questionings, were assessed for frequency and severity, and were classified for relatedness to study medication. Treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs), serious AEs, and TEAEs leading to study drug withdrawal were evaluated to assess the safety and tolerability of plecanatide.

Quality of life

The PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL questionnaires, as well as the PGA questionnaire, were completed at the clinic at baseline and at weeks 4, 8, 12 (end of treatment) and 14 (end of study). The PAC-SYM subscale assessed abdominal, rectal, and stool symptoms, and the PAC-QOL subscale assessed physical discomfort, psychosocial discomfort, worries/concerns, and satisfaction with bowel habits. The PGA questionnaire measured constipation severity throughout the study, as well as changes in constipation symptoms and treatment satisfaction, with the end-of-treatment form also assessing the patient’s desire to continue treatment.

Statistical analysis

Sample size determination for the current study was based on a previously completed multicenter, 12-week dose-ranging study of plecanatide in patients with CIC, with consideration of overall safety exposure requirements. Power calculation for the primary endpoint included the assumption that the durable overall CSBM responder rates for plecanatide 3 mg and 6 mg were equal. Under these assumptions, and based on a chi-squared continuity-corrected test with the intention of providing approximately 90% power at 5% significance level, enrolment of at least 450 patients per treatment arm was required to compare each active treatment arm with placebo. Categorical variables are summarized by the number and percentage of patients in each level, and continuous variables are summarized by number of observations, mean, and standard deviation. Where data were collected over time, the change from baseline is summarized at each time point.

Efficacy analyses were conducted using the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, which comprised all unique patients who were randomized into the study. Baseline values were derived from data collected in the 2-week pretreatment diary assessment prior to randomization: baseline mean CSBMs and SBMs per week were the combined average number of CSBMs and SBMs per week, and baseline stool consistency, severity of straining, and abdominal symptoms were the average of nonmissing patient scores reported.

For the responder analyses, patients who had fewer than four complete diary days were considered ‘nonresponders’ for that week. The diary was considered complete if the patient had recorded at least one daily BM Diary entry, including any rescue medication use. If a patient had between four and six assessments in a week, the calculations were based on a mean replacement approach method. Using this method, when diary data were missing in a week with partial data, the calculation of the overall CSBM/SBM rate during a given week was seven times the number of CSBMs reported divided by the number of days the patient reported bowel habits data. Patients with no assessments in a week were categorized as missing in the linear mixed model.

Secondary efficacy endpoints included the changes from baseline in mean weekly CSBMs, SBMs, straining scores, and stool consistency scores and were based on the least squares mean overall average estimate across the 12-week treatment period. Secondary endpoint comparisons between the placebo group and each plecanatide group were analyzed using a linear mixed-effects model with fixed effects for gender (stratification variable), treatment, week, interaction of treatment and week, and corresponding baseline value, and random intercept for patients.

Evaluation of patient-reported daily symptom scores were conducted using a linear mixed-effects model under the assumption of normally distributed residuals with treatment group, week, interaction of treatment and week, gender, and corresponding baseline value as fixed effects, and random intercept for patient. The comparisons of patients’ quality of life and constipation symptoms, which were measured using PAC-QOL and PAC-SYM questionnaires, were made by evaluation of changes from baseline for the total score between each plecanatide treatment and placebo using an analysis of covariance linear mixed-effects model with fixed effects for gender (stratification variable), treatment, week, interaction of treatment and week, and corresponding baseline value, and a random intercept for patient.

Data from the PGA questionnaire, including constipation severity, change in constipation symptoms, treatment satisfaction, and treatment continuation were summarized using descriptive statistics on observed data and change from baseline (where applicable). In addition, each assessment was analyzed separately at each visit using an analysis of covariance with fixed effects for gender (stratification variable) and treatment.

Times to first SBM and first CSBM were defined as the time from the first dose of study medication. Patients who did not have an SBM were censored at the time of their first ingestion of rescue medication (not <72 h after the first dose of study drug) or at the time of early termination, whichever was earlier. The primary analysis of time to first SBM compared each plecanatide treatment group versus placebo via a two-sided log-rank test stratified by gender. The functions of time to first SBM for each treatment group were estimated using the K-M product-limit method. Two-sided 95% confidence intervals for median time to first SBM and other quartiles were computed by treatment group; a similar analysis was performed for time to first CSBM.

Safety analyses utilized the safety population, which included all patients who received at least one dose of study medication. Evaluation of the safety of once-daily plecanatide over 12 weeks of dosing was based on the occurrence of TEAEs, vital signs, clinical laboratory assessments, and electrocardiograms as compared with those in the placebo group. AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA; version 14.1) classifications with reference to system organ class and preferred term.

The Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, stratified by gender, was used to hierarchically test the comparison between plecanatide 6 mg and placebo, and, separately, between plecanatide 3 mg and placebo. Holm-based tree-gatekeeping procedure was used for adjustment of p values to control the family-wise type I error rate at 5% (two-sided) by taking into account multiple doses and multiple primary endpoints. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.2 (or later; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) in a secure and validated environment.

Results

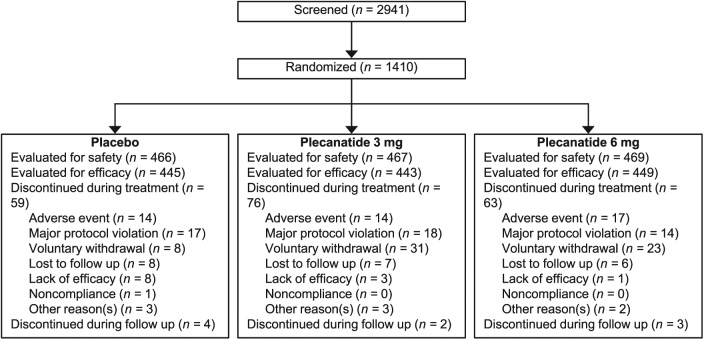

A total of 2941 patients were screened, of which 1410 patients were randomized to receive treatment. Eight randomized patients were not treated with study drug after being enrolled, which resulted in a safety population of 1402 patients (plecanatide 3 mg, n = 467; plecanatide 6 mg, n = 469; placebo, n = 466) and an ITT population of 1337 unique patients (plecanatide 3 mg, n = 443; plecanatide 6 mg, n = 449; placebo, n = 445; Figure 1). Treatment compliance across the three treatment groups was 97.5%, 96.7%, and 99.1% for the plecanatide 3 mg, plecanatide 6 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. Demographics and baseline characteristics were similar across treatment groups (Table 1). Approximately 20% of patients were male (range: 21.3% to 22.1%) and the mean age of patients ranged from 44.6 to 45.5 years across treatment groups. Notably, 21.0% of the patient population self-identified as Black/African American. Mean baseline weekly values were similar across treatment groups with respect to CSBMs, SBMs, stool consistency, abdominal discomfort, abdominal bloating, and straining scores (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the intent-to-treat population

| Placebo (n=445) | Plecanatide 3 mg (n=443) | Plecanatide 6 mg (n=449) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (range) | 44.6 (18–80) | 45.5 (18–80) | 45.3 (18–80) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 350 (78.7) | 345 (77.9) | 353 (78.6) |

| Male | 95 (21.3) | 98 (22.1) | 96 (21.4) |

| Race, n (%)* | |||

| White | 331 (74.4) | 341 (77.0) | 324 (72.2) |

| Black | 91 (20.4) | 88 (19.9) | 102 (22.7) |

| Asian | 14 (3.1) | 7 (1.6) | 11 (2.4) |

| Other | 9 (2.0) | 7 (1.6) | 12 (2.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 27.97 (5.08) | 28.59 (4.72) | 28.38 (4.86) |

| Weekly baseline values, mean±SD | |||

| CSBMs | 0.31±0.50 | 0.28±0.55 | 0.25±0.44 |

| SBMs | 1.55±1.59 | 1.79±2.05 | 1.60±1.66 |

| Stool consistencya | 2.35±1.09 | 2.16±1.03 | 2.28±1.11 |

| Straining scoreb | 2.41±0.85 | 2.45±0.85 | 2.47±0.88 |

| Abdominal bloatingc | 2.03±0.91 | 2.02±0.97 | 2.10±0.91 |

| Abdominal discomfortd | 1.91±0.99 | 1.92±1.01 | 2.02±0.98 |

Race was self-reported. Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Stool consistency was assessed with the use of the 7-point Bristol Stool Form Scale, where 1 indicates separate, hard lumps, like nuts (hard to pass); 2 indicates sausage-shaped but lumpy; 3 indicates like a sausage but with cracks on the surface; 4 indicates like a sausage or snake, smooth and soft; 5 indicates soft blobs with clear-cut edges (passed easily); 6 indicates fluffy pieces with ragged edges or a mushy stool; and 7 indicates watery, no solid pieces (entirely liquid).

The severity of straining at its worst during bowel movements was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale where: 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, 4 = very severe.

Abdominal bloating at its worst was rated on a 5-point Likert scale where 0=none, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe, and 4 very severe.

Abdominal discomfort at its worst was rated on a 5-point Likert scale where 0=none, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe, and 4=very severe.

BMI, body mass index; CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement; SBM, spontaneous bowel movement; SD, standard deviation.

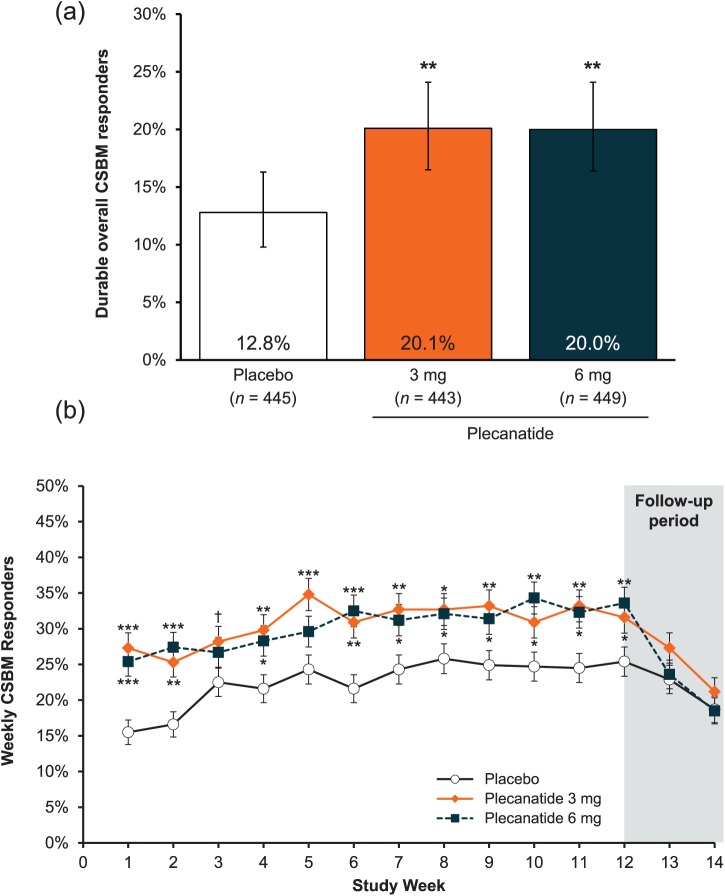

The percentage of patients who were durable overall CSBM responders after 12 weeks of treatment was statistically significantly greater with plecanatide 3 mg and 6 mg compared with placebo (3 mg = 20.1%; 6 mg = 20.0%; placebo = 12.8%; p = 0.004 for both comparisons; Figure 2a). The percentage of weekly CSBM responders in each plecanatide group was statistically greater than in the placebo group as early as week 1 (p < 0.001), and this remained consistent through the 12-week treatment period (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Percentage of patients in the intent-to-treat population who were durable overall complete spontaneous bowel movement responders, which was the primary efficacy endpoint.

**p < 0.01 versus placebo. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.Durable overall CSBM responders were defined as patients who fulfilled both ⩾3 CSBMs per week and an increase of ⩾1 CSBM from baseline in the same week for ⩾9 of the 12 treatment weeks, including ⩾3 of the last 4 weeks of treatment.

(b) Percentage of patients who were weekly complete spontaneous bowel movement responders.

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, †p = 0.05 (3 mg) versus placebo. Error bars represent standard error.

CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement.

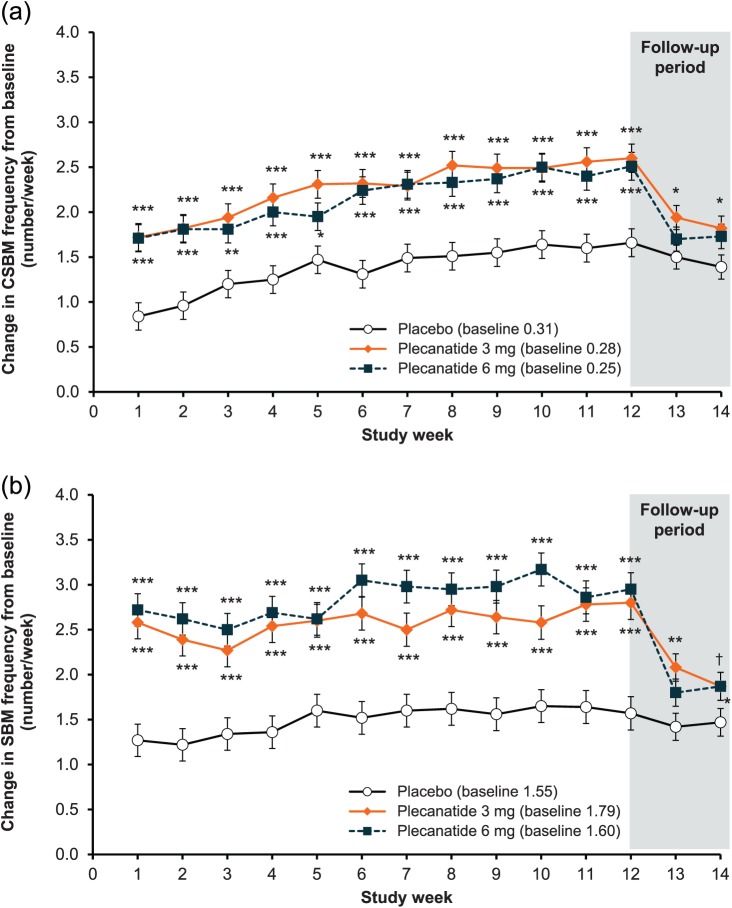

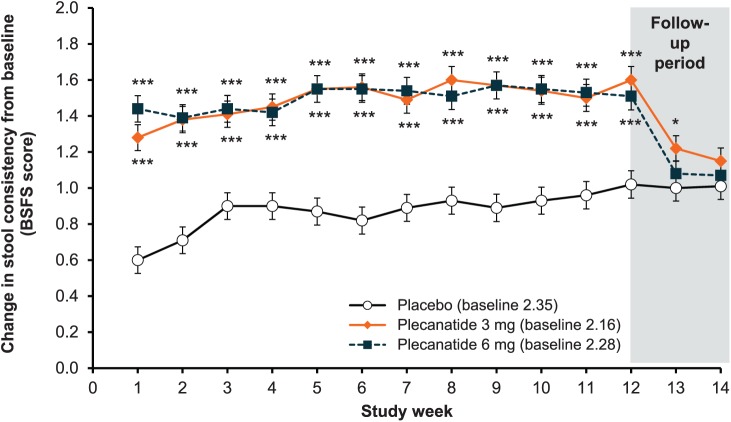

Both doses of plecanatide showed significant increases from baseline in mean weekly CSBM frequency relative to placebo, starting from week 1 and continuing throughout the 12-week treatment period (p < 0.001; Figure 3a). At the end of the follow-up period (week 14), mean weekly CSBM frequency had declined toward baseline levels, with no worsening compared with baseline. Similar to CSBM frequency, mean weekly SBM frequency increased significantly from baseline in each plecanatide treatment group starting from week 1 (p < 0.001). The statistically significant difference from placebo was sustained throughout the 12-week treatment period relative to placebo (Figure 3b), and, as expected in the post-treatment period, approached baseline levels by the end-of-study visit (week 14), with no worsening compared with baseline. Over the 12-week treatment period, improvement in stool consistency (as measured by an increase in mean BSFS score) was significantly greater in patients receiving plecanatide versus placebo (3 mg = 1.49; 6 mg = 1.50; placebo = 0.87; p < 0.001 for both doses; Figure 4). Rome criteria defines CIC symptoms as infrequent, difficult to pass or incomplete evacuation during defecation, thus, improvements in the frequency of weekly SBMs, CSBMs, and stool consistency may be considered the most clinically relevant improvement for patients.16

Figure 3.

(a) Change in weekly complete spontaneous bowel movement frequency from baseline.

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 versus placebo. Error bars indicated standard error.

(b) Change in spontaneous bowel movement weekly frequency from baseline.

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, †p = 0.051 (3 mg) versus placebo.

CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement; SBM, spontaneous bowel movement. Error bars indicate standard error.

Figure 4.

Change in weekly stool consistency from baseline, which was measured using the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS).

***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05 versus placebo. Error bars indicate standard error.

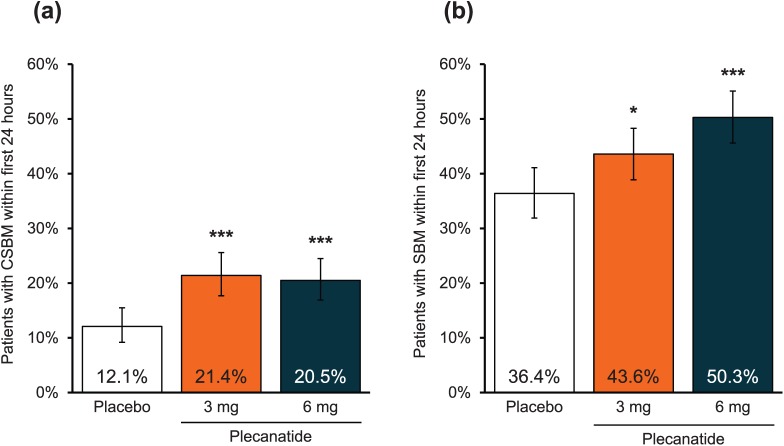

The initial onset of action of plecanatide was also evaluated. A significantly greater percentage of plecanatide-treated patients experienced a CSBM (p < 0.001 versus placebo for both doses) or an SBM (plecanatide 3 mg versus placebo, p < 0.05; plecanatide 6 mg versus placebo, p < 0.001) within 24 h of the first dose of study medication, and without the use of laxatives, compared with the placebo group (Figure 5a and 5b).

Figure 5.

(a) Percentage of patients with a complete spontaneous bowel movement within 24 h after the first dose of study medication.

***p < 0.001 versus placebo. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

(b) Percentage of patients with a spontaneous bowel movement within 24 h after the first dose of study medication.

***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05 versus placebo. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement; SBM, spontaneous bowel movement.

There was a statistically greater improvement from baseline in the severity of abdominal bloating at week 12 with plecanatide 3 mg (p = 0.007), and abdominal discomfort narrowly missed statistical significance (p = 0.054). There was numerically greater improvement from baseline for these two parameters with plecanatide 6 mg. Constipation severity was significantly improved from baseline with plecanatide 3 mg (−1.6 ± 0.06; p = 0.001 versus placebo) and plecanatide 6 mg (−1.5 ± 0.06; p = 0.022 versus placebo) compared with placebo (−1.3 ± 0.06; Table 2).

Table 2.

| Placebo (n = 445) |

Plecanatide 3 mg (n = 443) |

Plecanatide 6 mg (n = 449) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily symptom scores | |||

| Straining‡ | |||

| LS mean (SE) | −0.61 (0.040) | −0.89 (0.040) | −0.85 (0.040) |

| p value versus placebo | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Abdominal bloating severity | |||

| LS mean (SE) | −0.54 (0.040) | −0.69 (0.040) | −0.63 (0.040) |

| p value versus placebo | 0.007 | 0.084 | |

| Abdominal discomfort severity | |||

| LS mean (SE) | −0.57 (0.040) | −0.67 (0.040) | −0.62 (0.040) |

| p value versus placebo | 0.054 | 0.365 | |

| Patient Global Assessments | |||

| Constipation severity | |||

| LS mean (SE) | −1.3 (0.06) | −1.6 (0.06) | −1.5 (0.06) |

| p value versus placebo | 0.002 | 0.022 | |

| Change in constipation | |||

| LS mean (SE) | 2.6 (0.05) | 2.2 (0.06) | 2.2 (0.05) |

| p value versus placebo | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Treatment satisfaction§ | |||

| LS mean (SE) | 3.1 (0.07) | 3.5 (0.07) | 3.5 (0.07) |

| p value versus placebo | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Treatment continuation§ | |||

| LS mean (SE) | 3.2 (0.07) | 3.5 (0.07) | 3.6 (0.07) |

| p value versus placebo | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Patient Assessment of Constipation | |||

| Patient Assessment of Constipation–Symptoms | |||

| LS mean (SE) | −0.94 (0.044) | −1.12 (0.045) | −1.10 (0.045) |

| p value versus placebo | 0.002 | 0.009 | |

| Patient Assessment of Constipation–Quality of Life | |||

| LS mean (SE) | −0.92 (0.044) | −1.13 (0.045) | −1.11 (0.045) |

| p value versus placebo | <0.001 | 0.001 | |

Represents LS mean (SE) change score at week 12.

Increased change in constipation score indicates improvement; for all other scales, negative change from baseline indicates improvement.

Represents overall average LS mean change score over 12 weeks of treatment.

Not a change score.

BSFS, Bristol Stool Form Scale; LS, least squares; SE, standard error.

Plecanatide 3 mg and 6 mg demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in straining scores compared with placebo, indicative of overall less BM straining due to plecanatide treatment (Table 2). The mean differences from placebo in straining score were −0.27 and −0.24 for plecanatide 3 mg and 6 mg, respectively, with a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001) compared with placebo observed as early as week 1, and remained consistent through the end of treatment at week 12. Straining scores increased toward baseline levels, as expected during the post-treatment follow-up period, with no worsening compared with baseline.

The effects of plecanatide compared with placebo were evaluated using several patient assessment tools of constipation symptoms and health-related quality of life. PGAs showed that constipation severity was significantly reduced with each plecanatide dose compared with placebo (Table 2). The mean change in PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL scores from baseline showed significant improvements for plecanatide-treated patients compared with placebo at week 12 (Table 2). Following the cessation of treatment, PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL total scores in the active treatment groups declined to levels similar to the placebo-treated group. In addition, patient satisfaction and intention to continue treatment were significantly greater for each plecanatide dose compared with placebo (Table 2).

The safety profile in the plecanatide groups was similar to that of the placebo group, and TEAEs were predominantly mild to moderate in severity. A total of 372 patients (26.5%) experienced ⩾1 TEAE (Table 3). The incidence of TEAEs with plecanatide 3 mg (25.7%) and 6 mg (29.2%) was similar to that seen in placebo-treated patients (24.7%). Rates of diarrhea were 3.2% (plecanatide 3 mg), 4.5% (plecanatide 6 mg), and 1.3% (placebo).

Table 3.

Summary of treatment-emergent adverse events (safety population).

| Patients, n (%) | Placebo (n = 466) |

Plecanatide 3 mg (n = 467) |

Plecanatide 6 mg (n = 469) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ⩾1 TEAE | 115 (24.7) | 120 (25.7) | 137 (29.2) |

| ⩾1 Severe TEAE | 6 (1.3) | 8 (1.7) | 6 (1.3) |

| ⩾1 Serious AE* | 8 (1.7) | 8 (1.7) | 4 (0.9) |

|

TEAE experienced by ⩾2.0%

of patients in any treatment group |

|||

| Diarrhea | 6 (1.3) | 15 (3.2) | 21 (4.5) |

| Headache | 9 (1.9) | 10 (2.1) | 10 (2.1) |

| Discontinued study medication | |||

| Due to TEAE | 14 (3.0) | 15 (3.2) | 18 (3.8) |

| Due to diarrhea | 2 (0.4) | 5 (1.1) | 5 (1.1) |

Four of the 16 serious AEs were pregnancies, as sites were instructed to capture all pregnancies as serious AEs. Pregnancies were reported in each of the treatment groups: two in the placebo group and one each in the plecanatide 3 mg and 6 mg groups; therefore, a total of six (1.3%), seven (1.7%), and three (0.7%) patients with serious AEs were reported for the placebo, plecanatide 3 mg, and plecanatide 6 mg groups, respectively.

AE, adverse event; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

A total of 16 patients (4.3% of patients reporting ⩾1 TEAE) experienced 18 serious AEs during treatment: six patients with seven events in the placebo group, seven patients with eight events in the plecanatide 3 mg group, and three patients with three events in the plecanatide 6 mg group. Four of the serious AEs were pregnancies that were reported during the treatment period, two of which were in patients receiving plecanatide. Only one of the serious AEs, a liver function test abnormality that occurred with plecanatide 6 mg, was considered possibly related to study drug. In this patient, elevations in alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase began at week 4 and were considered severe and serious at week 8 (alanine aminotransferase 193 IU/l and aspartate aminotransferase 83 IU/l). The patient reported concomitant indomethacin use and elevations persisted after discontinuing study drug, suggesting the liver function test abnormality may not have been related to plecanatide.

Discontinuations due to TEAEs occurred in 3.2% (plecanatide 3 mg), 3.8% (plecanatide 6 mg), and 3.0% (placebo) of patients. Rates of discontinuation due to diarrhea were low, occurring in 1.1% of patients in each plecanatide group and 0.4% in the placebo-treated group. No unexpected safety signals were observed in this study and no deaths were reported. Laboratory findings, vital signs, and physical examinations were all unremarkable, with low incidence of any clinically important changes.

Discussion

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study demonstrated that plecanatide 3 mg or 6 mg once daily resulted in a statistically significant improvement in durable overall CSBM responder rates relative to placebo. Improvements from baseline in CSBM and SBM frequency and stool consistency were noted as early as week 1 and were sustained through the end of treatment. Significantly more patients in the plecanatide groups had positive results compared with placebo on multiple secondary endpoints including straining, bloating, treatment satisfaction, and desire to continue treatment. The high degree of similarity between the results presented herein and those of Miner and colleagues14 including for the primary endpoint, key secondary endpoints, and safety data, demonstrates the reproducibility of the activity of plecanatide in adult patients with CIC, in the two largest phase III CIC clinical trials to date.

Individuals who live with CIC experience a substantial impact on their day-to-day lives, and many find treatment to be unsatisfactory. A recent survey17 of 1673 adult patients with CIC found that nearly one in four (23%) reported poor quality of life (PAC-QOL global score above the 75th percentile) due to their disease. In another cross-sectional population survey, patients with CIC and abdominal symptoms experienced a mean of 3.2 days per month with loss of productivity.2 More than half of the patients surveyed on the symptomatology of their disease listed gas pain, constipation, and straining as very/extremely bothersome. Moreover, 36% of patients who sought physician care were not satisfied with treatment. In the current study, the desire to continue treatment, treatment satisfaction, and PAC-QOL scores of plecanatide-treated patients appeared to correlate with clinically meaningful improvement of their BM frequency and consistency.

Treatment with plecanatide 3 mg or 6 mg was generally safe well tolerated. The majority of TEAEs were mild to moderate in severity, and rates of diarrhea, the most frequently reported TEAE, were low (3 mg = 3.2%; 6 mg = 4.5%; placebo = 1.3%). Rates of discontinuation due to TEAEs in the active treatment groups were also low and were similar to rates in the placebo-treated group. Treatment with plecanatide was also associated with greater treatment satisfaction scores and continuation scores.

Results of this study are consistent with those of the previously reported study of similar design14 across primary and secondary endpoints. The two studies are the largest double-blind studies conducted in CIC so far. It is notable that in our study and the one abovementioned, the durable overall CSBM responder was defined as a weekly responder for ⩾9 of the 12 treatment weeks, including ⩾3 of the final 4 weeks of treatment. This is a more stringent definition than that used previously in clinical evaluations of other CIC treatments.18–22

The pH-sensitive activity of plecanatide may be responsible for the combination of efficacy and safety findings in this phase III study. Plecanatide is the first analog of uroguanylin to be assessed and approved for the treatment of CIC. Uroguanylin is an endogenous 16-amino-acid peptide containing two disulfide bonds,23 and is predominantly expressed in the small intestine with a gradation of expression from higher to lower along the rostrocaudal axis. Uroguanylin exerts its biologic activity in a pH-sensitive manner, which coincides with intestinal compartments responsible for fluid secretion.24 Plecanatide binds to and activates the GC-C receptor, which is believed to induce net fluid secretion that leads to softening of stools, durable improvement in frequency of CSBMs and SBMs, and improvement in secondary CIC symptoms. Plecanatide activity has a pH-sensitive profile similar to that of uroguanylin and differs from linaclotide, another GC-C receptor agonist, in that regard.25 Plecanatide acts locally in the small intestine, with no evidence of systemic absorption in patients with CIC.25

The strengths of this study include its randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, well-controlled design, as well as the large number of patients (>1300) included for analysis. This study has the limitation of providing information over the short term (12 weeks); however, a long-term open-label study assessing the safety profile of plecanatide over 52 weeks has been completed and will be published separately.

Once a diagnosis of CIC has been established, the American Gastroenterological Association recommends a step-wise approach for treatment based on symptom relief.26 Treatment begins with a gradual increase in dietary fiber intake and osmotic laxatives, such as polyethylene glycol. If the desired response is not achieved, patients step to stimulant laxatives, such as bisacodyl. Should the desired relief still not be achieved then newer prescription agents are available with different mechanisms. These agents include: lubiprostone, a chloride channel type 2 activator and prostaglandin analog27; linaclotide, a GC-C agonist and analog of Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin (STa)28,29; and plecanatide, a GC-C agonist and analog of human uroguanylin.9 Lubiprostone should be administered twice daily with food. Both plecanatide and linaclotide are once-daily medications, with linaclotide recommended for administration 30 min before eating, while plecanatide can be administered with or without food. No head-to-head trials comparing these medications have been conducted thus far, so the appropriate choice of prescription medication should be based on the clinical profile of each patient.

Plecanatide 3 mg and 6 mg, when administered orally once daily for 12 weeks, demonstrated a durable improvement in constipation and related CIC symptoms, compared with placebo. A significantly larger percentage of patients achieved the primary durable overall CSBM responder endpoint. Significant improvements in BM frequency and stool consistency were rapid and sustained throughout the treatment period and were accompanied by improvements in straining and abdominal symptoms, resulting in general improvements in quality of life, treatment satisfaction, and desire to continue treatment. In patients with CIC, plecanatide was well tolerated, exhibiting a limited AE profile, with a low incidence of diarrhea. Plecanatide appears to be a promising new treatment for adult patients with CIC and has recently gained approval in the US for this indication.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the patients who participated in this study and the clinicians who contributed their efforts to the conduct of the study. The authors also wish to thank Ann Sherwood, PhD, Nicole Coolbaugh, and Philip Sjostedt, BPharm, of The Medicine Group, LLC (New Hope, PA), who provided medical writing and editorial assistance that was funded by Synergy Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded in full by Synergy Pharmaceuticals Inc. Synergy Pharmaceuticals Inc. also provided the plecanatide and placebo used for the study.

Conflict of interest statement: KS and PG are employees and stockholders of Synergy Pharmaceuticals Inc. At the time of the study and of manuscript preparation, LB and BK were employees and stockholders of Synergy Pharmaceuticals Inc. MD states no potential conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Michael DeMicco, Anaheim Clinical Trials, Anaheim, CA, USA.

Laura Barrow, Synergy Pharmaceuticals Inc., New York, NY, USA.

Bernadette Hickey, Synergy Pharmaceuticals Inc., New York, NY, USA.

Kunwar Shailubhai, Synergy Pharmaceuticals Inc., New York, NY, USA.

Patrick Griffin, Executive Vice President and Chief Medical Officer, Synergy Pharmaceuticals Inc., 420 Lexington Avenue, Suite 2012, New York, NY 10170, USA.

References

- 1. Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EM, et al. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100(Suppl. 1): S5–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heidelbaugh JJ, Stelwagon M, Miller SA, et al. The spectrum of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: US survey assessing symptoms, care seeking, and disease burden. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110: 580–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Suares NC, Ford AC. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 1582–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cai Q, Buono JL, Spalding WM, et al. Healthcare costs among patients with chronic constipation: a retrospective claims analysis in a commercially insured population. J Med Econ 2014; 17: 148–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Camilleri M. Guanylate cyclase C agonists: emerging gastrointestinal therapies and actions. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: 483–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vaandrager AB, Smolenski A, Tilly BC, et al. Membrane targeting of cGMP-dependent protein kinase is required for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl- channel activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 1466–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Toriano R, Ozu M, Politi MT, et al. Uroguanylin regulates net fluid secretion via the NHE2 isoform of the Na+/H+ exchanger in an intestinal cellular model. Cell Physiol Biochem 2011; 28: 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Busby RW, Bryant AP, Bartolini WP, et al. Linaclotide, through activation of guanylate cyclase C, acts locally in the gastrointestinal tract to elicit enhanced intestinal secretion and transit. Eur J Pharmacol 2010; 649: 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shailubhai K, Palejwala V, Arjunan KP, et al. Plecanatide and dolcanatide, novel guanylate cyclase-C agonists, ameliorate gastrointestinal inflammation in experimental models of murine colitis. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2015; 6: 213–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu D, Overbey D, Watkinson LD, et al. In vivo imaging of human colorectal cancer using radiolabeled analogs of the uroguanylin peptide hormone. Anticancer Res 2009; 29: 3777–3783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shailubhai K, Comiskey S, Foss JA, et al. Plecanatide, an oral guanylate cyclase C agonist acting locally in the gastrointestinal tract, is safe and well-tolerated in single doses. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58: 2580–2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miner PB, Surowitz R, Fogel R, et al. 925g Plecanatide, a novel guanylate cyclase-C (GC-C) receptor agonist, is efficacious and safe in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC): results from a 951 patient, 12 week, multi-center trial [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2013; 144: S-163. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shailubhai K, Talluto C, Comiskey S, et al. A phase IIa randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled, 14-day repeat, oral, range-finding study to assess the safety, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of plecanatide (SP-304) in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation (Protocol No. SP-SP304201–09). Poster presented at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) New Orleans, LA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miner PB, Jr, Koltun WD, Wiener GJ, et al. A randomized phase III clinical trial of plecanatide, a uroguanylin analog, in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112: 613–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997; 32: 920–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mearin F, Ciriza C, Minguez M, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and functional constipation in the adult. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2016; 108: 332–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Flourie B, Not D, Francois C, et al. Factors associated with impaired quality of life in French patients with chronic idiopathic constipation: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 28: 525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lacy BE, Schey R, Shiff SJ, et al. Linaclotide in chronic idiopathic constipation patients with moderate to severe abdominal bloating: a randomized, controlled trial. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0134349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lembo AJ, Schneier HA, Shiff SJ, et al. Two randomized trials of linaclotide for chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 527–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2344–2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tack J, van Outryve M, Beyens G, et al. Prucalopride (Resolor) in the treatment of severe chronic constipation in patients dissatisfied with laxatives. Gut 2009; 58: 357–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Quigley EM, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R, et al. Clinical trial: the efficacy, impact on quality of life, and safety and tolerability of prucalopride in severe chronic constipation – a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 29: 315–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kita T, Smith CE, Fok KF, et al. Characterization of human uroguanylin: a member of the guanylin peptide family. Am J Physiol 1994; 266: F342–F348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hamra FK, Eber SL, Chin DT, et al. Regulation of intestinal uroguanylin/guanylin receptor-mediated responses by mucosal acidity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94: 2705–2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Comiskey S, Foss J, Jacob G, et al. Orally administered plecanatide, a guanylate cyclase-C agonist, acts in the lumen of the proximal intestine to facilitate normal bowel movement in mice and monkeys. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: S700. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bharucha AE, Dorn SD, Lembo A, et al. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology 2013; 144: 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cuppoletti J, Malinowska DH, Tewari KP, et al. SPI-0211 activates T84 cell chloride transport and recombinant human ClC-2 chloride currents. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2004; 287: C1173–C1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weiglmeier PR, Rösch P, Berkner H. Cure and curse: E. coli heat-stable enterotoxin and its receptor guanylyl cyclase C. Toxins (Basel). 2010; 2: 2213–2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pattison AM, Blomain ES, Merlino DJ, et al. Intestinal enteroids model guanylate cyclase C-dependent secretion induced by heat-stable enterotoxins. Infect Immun 2016; 84: 3083–3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]