Abstract

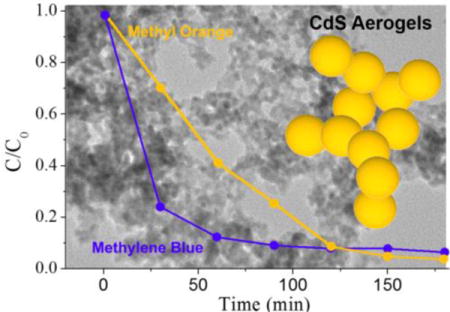

Synthesis of efficient photocatalysts based on CdS nanomaterials for oxidative decomposition of organic effluents typically focuses on (a) enhancement of surface area of the catalysts and (b) promotion of the separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs. CdS aerogel, which are synthesized by simple sol–gel assembly of discrete nanocrystals (NCs) into a porous network followed by supercritical drying, could provide higher surface area for photocatalytic reactions along with facile charge separation due to direct contact between NCs via covalent bonding. We evaluated the efficiency of CdS aerogel materials for degradation of organic dyes using methylene blue (MB) and methyl orange (MO) as test cases. CdS aerogel materials exhibited remarkable photocatalytic activity for dye degradation compared to typical, ligand-capped CdS NCs. The catalytic efficiency of CdS aerogels was further improved by decreasing the chain-length and extent of surface organics, leading to higher, and more hydrophilic, accessible surface area. The use of porous, chalcogenide-based solid state architectures for photocatalysis enables easy separation of catalyst while ensuring a high-interfacial surface area for analyte reactivity and visible light activation.

TOC image

CdS aerogel photocatalysts enable a high-interfacial surface area for analyte reactivity and visible light activation.

Introduction

Potable water is increasingly becoming scarcer all over the world, making water purification methods and research seeking to improve them all the more vital. Organic pollutants in industrial and agricultural wastewater pose a great threat to aquatic life and other living organisms due to their hazardous nature. Semiconductor photocatalysts have tremendous potential for remediation of organic effluents in wastewater due to their ability to decompose organic contaminants simply under light irradiation, and this provides a low-cost, yet effective water-purification method. In the process of photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants, electron-hole pairs are generated in the semiconductor catalysts as a result of absorption of light. Photogenerated electron-hole pairs then travel to the catalyst surface and produce active oxygen radical species that cause the degradation of dye molecules. TiO2, which is a wide bandgap semiconductor, is a cheap, stable and environmentally benign photocatalyst widely used for the photodegradation of organic dyes under UV illumination. However, in order to use TiO2 as an effective visible light photocatalyst, modifications must be made to enhance the visible light absorption by doping with metals (cationic doping),1, 2 nonmetals (anionic doping),3, 4 or both metals and nonmetals (co-doping).5, 6, 7

CdS nanomaterials have emerged as visible-light-driven photocatalysts for water remediation because of the correspondence of their band gap to visible light. Increasing the surface area of the catalysts and suppression of electron-hole recombination are key aspects in the development of efficient CdS-based photocatalysts. The synthesis of CdS nanostructures with different morphologies (e.g. cubelike nanostructures8, mesoporous nanospheres9, hollow spheres,10, 11 dendritic nanoarchitectures12, branched nanowires13) is the most general approach to increase the surface area of the catalysts. With respect to recombination of photogenerated charge carriers, this can be suppressed by enhancing the charge separation efficiency via formation of nanocomposites with semiconductors (e.g. TiO2/CdS14, 15, ZnO/CdS16, Bi2S3/CdS17, MoO3/CdS18, SnO2/CdS19 or metal ion doping10, and this also improves the stability of CdS, which is otherwise prone to photocorrosion.

Aerogels composed of visible-light-absorbing semiconductor matrices combine an interconnected pore structure (for facile molecular transport) with a semiconducting nanostructure (for facile charge transport), thereby potentially enabling efficient photocatalysis. Indeed, chalcogels based on Fe-S biomimetic molecular clusters have been demonstrated to be active solar fuel catalysts for nitrogen fixation and hydrogen generation.20–24 We have adopted a different approach to chalcogenide aerogel formation, based on sol-gel assembly of metal chalcogenide nanocrystals (NCs) to form a porous, high surface area network.25, 26 Photocurrent studies suggest that the direct contact of individual nanocrystals within the porous NC network via dichalcogenide bonding27 facilitates the charge carrier separation, which in turn reduces the electron-hole pair recombination.28, 29 This provides a unique and convenient strategy to address the key issues related to exploitation of CdS NCs as photocatalysts. In this study, we explore the catalytic efficiency of CdS aerogel materials for degradation of organic dyes under visible light irradiation using methylene blue (MB) and methyl orange (MO) as test cases. Furthermore, we address some of the issues associated with sol–gel assembly of CdS NCs that can hinder the efficiency of photocatalytic activity.

Experimental Section

Materials

Trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO, 90%), tetranitromethane (TNM), thioglycolic acid (98%), and 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA, 95%) were purchased from Aldrich. Cadmium oxide (99.999%), sulfur (99.999 %) and titanium (IV) oxide nanopowder were purchased from Strem Chemicals. 1-tetradecylphosphonic acid (TDPA, 98%) was purchased from Alfa-Aesar, and tetramethylammonium hydroxide pentahydrate (TMAH, 97%), methylene blue (MB) and methyl orange (MO) were purchased from ACROS. Oleylamine (>40%) was purchased from TCI America. Toluene, methanol, butanol and ethyl acetate were purchased from Mallinckrodt. TOPO was distilled before use; all the other chemicals were used as received.

Synthesis of CdS nanocrystals (NCs)

High quality CdS NCs were synthesized following a literature procedure with modifications.30, 31 In a typical synthesis of CdS NCs, 0.0514 g (0.4 mmol) of CdO, 3.7768 g (9.77 mmol) of TOPO and 0.115 g (0.4 mmol) of TDPA were heated at 340°C under Ar for 4 hours (until a colorless solution forms). Simultaneously, the S precursor solution was prepared by stirring 0.013 g (0.4 mmol) of S into 3 mL oleylamine at room temperature, under Ar, for 2 hours. The reaction temperature was then decreased to 255°C, and the S precursor solution was injected. The color of the mixture changed to yellow immediately and the NCs were grown at 255°C for 30 min. As-prepared NCs were then dispersed in hexane and centrifuged to remove unreacted precursors, and then precipitated using a butanol/methanol mixture. This purification procedure was repeated once.

MUA/thioglycolic acid exchange

After purification, the thiolate ligand exchange was performed by stirring the nanocrystals for several hours into an MUA- or thioglycolic acid-methanol solution (0.3678g (1.6 mmol) of MUA in 10 mL methanol or 0.11 mL (1.6 mmol) of thioglycolic acid in 10 mL methanol), adjusted to pH ~11 using TMAH. The MUA or thioglycolic acid-capped NCs were precipitated using an ethyl acetate/toluene mixture, centrifuged, washed with ethyl acetate and finally dispersed in 8 mL methanol to make NC sol.

Synthesis of CdS aerogels

The CdS NC sol was divided into four vials and gelation was initiated by adding 50 μL of 3% TNM to each vial. The sols were allowed to gel, and wet gels were aged for several days and exchanged with acetone to remove byproducts. After solvent exchange, the gels were dried into aerogels using a critical point dryer (CPD) as described elsewhere.32 Monolithic aerogels were crushed to form a powder for photocatalytic studies. For studies with annealed aerogels, the samples were heated at 250 °C for 30 min under Ar.

Materials characterization

Transmission electron microscopic (TEM) imaging was carried out on a JEOL 2010 transmission electron microscope operated at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) was performed on a Rigaku Diffractometer (RU200B) using the Kα line of a Cu rotating anode source (40 kV, 150 mA). PL and UV–vis spectra were obtained with a Cary Eclipse (Varian, Inc.) fluorescence spectrometer and a Cary 50 (Varian Inc.). Aerogels were sonicated in toluene to form a dispersion for optical studies. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) measurements were performed on a Perkin Elmer, Pyris 1 TGA under nitrogen flow. The surface area of samples was determined by obtaining nitrogen physisorption isotherms on samples at 77 K by using a Micromeritics TriStar II 3020 surface area analyzer and fitting the data using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) model. Samples were prepared for physisorption by treating under a He flow at 150 C for several hours. Infrared Spectroscopy (IR) measurements were carried out using a Bruker Tensor 27 FTIR spectrometer to detect the surface organic groups on the aerogels before and after catalysis. A powder of CdS aerogel catalyst or methylene blue was ground with dry KBr to yield a uniform mixture, and this mixture was pressed into a transparent pellet by applying 2000 psi of pressure using a Carver Hydraulic pellet press.

Photocatalytic activity measurements

The efficiency of photocatalysts for dye degradation was evaluated by degradation of MB and MO in aqueous solution under visible-light irradiation. A custom built reactor consisting of a water-jacketed 1000 mL Pyrex beaker, 450 W mercury-vapor lamp covered with a uranium glass filter (cutoff wavelength 350 nm) and a quartz water jacket was employed to perform photocatalytic reactions. The beaker was connected to a water bath and to the quartz water jacket of the light source. Prior to the photocatalytic reaction, 10 mg of each photocatalyst (powdered from a monolith) was added to 30 mL of MB or MO solution (5.0 × 10 −5 M) in beakers and the solution was magnetically stirred for 30 minutes in the dark to ensure an adsorption–desorption equilibrium between the photocatalyst and MB or MO. For the photocatalytic reaction, sample beakers were placed in the 1000 mL Pyrex beaker with circulating water jacket and then irradiated with light for 3 hours under continuous stirring. The reaction temperature was monitored with a temperature probe placed between the sample beakers and immersed in the water bath. Aliquots (0.5 mL) were taken out every 30 minutes, centrifuged to remove catalyst particles, and the concentration of MB or MO was determined by UV–vis spectroscopic measurements after appropriate dilution. For the recyclability test, the used aerogel was isolated by centrifuging, dried under dark conditions and then added into another 30 mL of MB solution (5.0 × 10 −5 M).

Total organic carbon (TOC) of the initial and irradiated samples were measured with a Shimadzu TOC-VCSH analyzer. TOC removal efficiency was calculated by following equation:

Where TOC(0) and TOC(2) are the TOC values at reaction time 0 and 2, respectively.

Results & Discussion

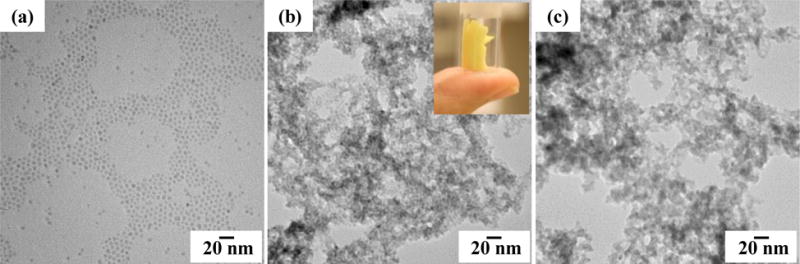

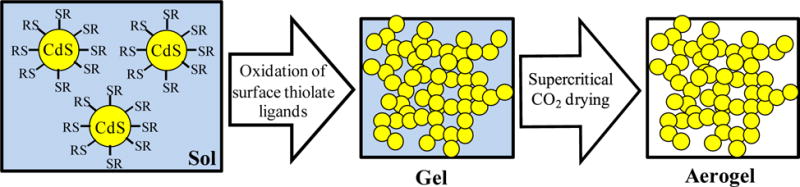

CdS nanocrystals (NCs) were synthesized following standard protocols.30 Fig. 1a and Fig. S1a, ESI† show TEM images of as-synthesized NCs capped with trioctylphosphine (TOPO) ligands consistent with an average size of 4–6 nm. The CdS NCs had a low degree of polydispersity, as indicated by the narrow emission peak (FWHM: 26–27 nm) in the PL spectrum of TOPO-capped NCs, and the diameter of the NCs is 5.1 nm, as estimated from the first excitonic peak in the UV–vis spectrum of TOPO-capped NCs, (Fig. S1b, ESI†).33 In order to form CdS aerogels, the original ligands were exchanged with thiolate ligands (11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA) or thioglycolic acid, under basic conditions). The resultant thiolate-capped NCs were dispersed in methanol to make the sol and gelation was initiated by adding tetranitromethane (TNM). As shown in Scheme 1, TNM oxidatively removes thiolate ligands irreversibly from the CdS NC surface (as disulfides, RS-SR), and subsequent oxidation of exposed surface sulfide leads to assembly of NCs via interparticle disulfide (S-S2−) bonding. The detailed chemical mechanism involved in this process is described elsewhere.27 This controlled aggregation of NCs results in cluster formation followed by cluster growth, and at the gel point, clusters overlap to form the wet gel network.34 In order to form aerogels, the gel was exchanged with liquid CO2, and finally dried under supercritical conditions, enabling the CO2 solvent to be removed without inducing pore collapse, thus maintaining the integrity of the gel.

Fig. 1.

TEM images of (a) TOPO-Capped CdS NCs, and aerogels formed by (b) MUA- and (c) thioglycolic acid-capped NCs. Inset: picture of a CdS aerogel monolith prepared from MUA-capped NCs.

Scheme 1.

Scheme showing the main steps involved in formation of CdS aerogels from thiolate capped-CdS NCs.

UV/visible spectroscopy of aerogels relative to precursor particles reveal no change in absorption onset (ca 2.7 eV), suggesting the low-dimensionality of the network enables the quantum confinement to be maintained (Fig. S1, ESI†). TEM images of the aerogels are consistent with the low-dimensional network, and reveal the porous nature of the aerogel materials (Fig. 1b and c). Although aerogels are formed by assembly of discrete NCs, they do not grow during this process, or even after heating at 250 °C, as indicated by the negligible changes in the PXRD patterns (Fig. S2, ESI†; peak narrowing is expected if the crystallites grow in size, in accordance with the Scherrer Equation).

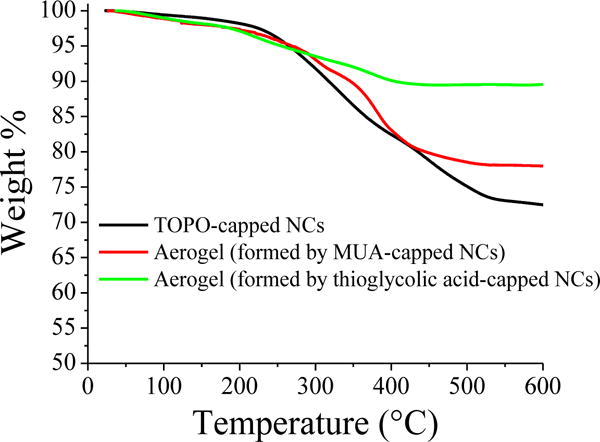

In an ideal case, aerogels comprise a porous network of NCs with complete absence of surface ligands. However, in practice, we always observe some quantity of residual ligands on the surface of the NC building blocks,28, 35 which is expected to reduce the accessible surface area and control the wetting characteristics of the resultant aerogel (hydrophobicity). The efficiency of removal of surface thiolate ligands by oxidation has been shown to be primarily dependent on the chain length.29 In addition, it can be assumed that dye molecules have easier accessibility to the catalytic surface when the residual ligands (terminated with carboxylates) have shorter alkyl chains due to reduced sterics and hydrophobicity. Accordingly, we studied the consequences of chain length on the sol–gel process and the activity of resultant aerogels by producing aerogels from CdS NCs capped with both long-chain MUA (11-carbon) and short-chain thioglycolic acid (2-carbon) functionalities. The TGA curves of aerogels (Fig. 2) demonstrated a noticeable decrease of weight loss from 22% (for MUA) to 11% (for thioglycolic acid) indicative of less carbon content in aerogels produced by thioglycolic acid capped-CdS NCs. Compared to aerogels, typical TOPO-capped NCs showed a larger weight loss (28 %) suggesting a higher (by mass) surface coverage of the ligands, as expected.

Fig. 2.

TGA curves of TOPO-capped CdS NCs, and aerogels produced from MUA and thioglycolic acid-capped CdS NCs.

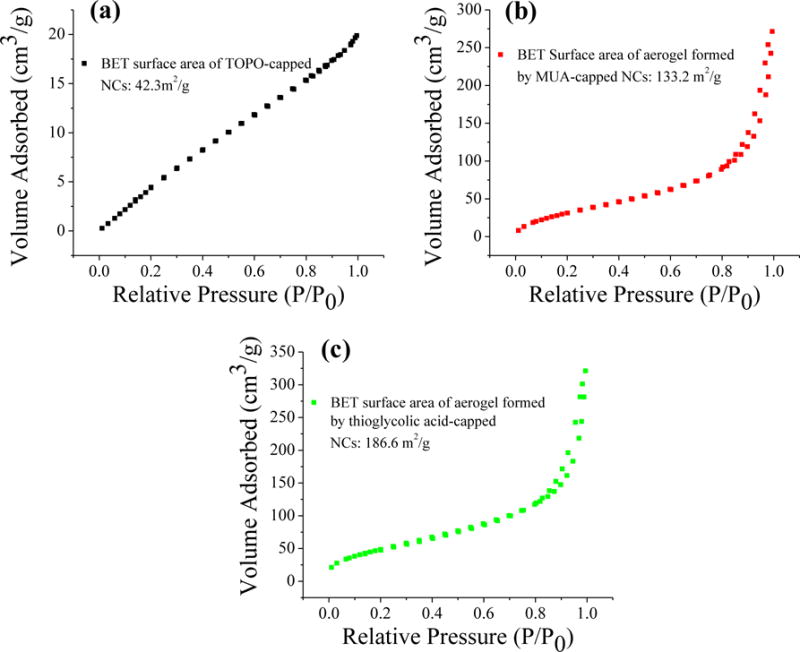

Importantly, surface area measurements clearly showed the increase of accessible surface area for aerogels formed by shorter thioglycolic acid-capped NCs (Fig. 3). Application of Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis to nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms of the two aerogel samples results in a significantly higher surface area for the aerogel synthesized from thioglycolic acid-capped CdS NCs (186.6 m2/g) than for the aerogel synthesized from MUA capped-CdS NCs (132.2 m2/g). Moreover, the surface area of TOPO-capped NCs (42.3 m2/g) is much lower than both types of aerogel confirming the fact that a significant increase of surface area in the solid-state is achieved by formation of a porous network of CdS NCs via sol–gel process.

Fig. 3.

Nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms for (a) TOPO-Capped CdS NCs, and aerogels formed by (b) 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA) and (c) thioglycolic acid-capped NCs.

In order to evaluate the catalytic activity of CdS aerogel materials relative to CdS NCs, we monitored the degradation of MB (5.0 × 10−5 M) under in the dark and under visible light irradiation over different photocatalysts (10 mg). Visible light degradation was also studied in the absence of a catalyst (to probe the dye stability under our illumination conditions). The mixtures were pre-equilibrated for 30 minutes in the dark and then 0.5 mL aliquots were withdrawn at 30 minute intervals after initiating the visible light irradiation using a 450 W mercury-vapor lamp covered with a uranium glass filter (cutoff wavelength 350 nm). After centrifuging to remove catalyst particles, 0.1 mL of each aliquot was diluted to 1.0 mL and UV–vis spectra were obtained to determine the MB concentration.

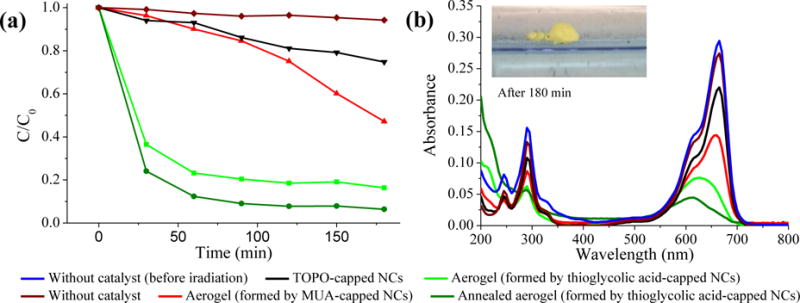

Fig. 4a shows the photocatalytic MB degradation activity of different catalysts with time and Fig. 4b shows the corresponding spectra after 3 hours of irradiation. In the absence of a catalyst, there is only a slight decrease of MB concentration (< 5%) indicative of minimal self-degradation of MB under the conditions used to perform the dye degradation experiment. All the CdS materials resulted in degradation of MB after three hours of irradiation time, confirming the visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity. In agreement with our hypothesis, CdS aerogels formed by MUA-capped CdS NCs exhibited enhanced catalytic activity compared to TOPO-capped CdS NCs. Enhanced activity in the aerogels is attributed to the interconnected conductive network and the reduced number of capping groups on the primary particle surfaces due to the irreversible ligand elimination that is integral to the gelation mechanism (Fig. 2 & 3). Attempts to perform similar studies using MUA-capped CdS nanoparticles (rather than TOPO-capped), resulted in photocorrosion and aggregation of the particles and dye decomposition was accompanied by dye adsorption (Fig. S3, ESI†). Aerogels synthesized by thioglycolic acid-capped NCs showed superior activity, and a more rapid MB degradation rate at the early stages of the reaction compared to aerogels synthesized by MUA-capped NCs, attributable in part to the enhancement in accessible surface area and reduction in hydrophobicity achieved by employment of the shorter-chain mercaptoalkyl acid in the ligand exchange step. As shown in the Fig. 4b inset, MUA-capped CdS aerogels are characterized by low-densities and poor wetting, thus the monoliths can actually “float” on the surface of the aqueous solution containing the analyte. Annealing of the aerogels at 250 °C under inert atmosphere (Ar) results in ligand loss (based on TGA) and further improvements in activity (ca 40× the initial rate of TOPO-capped CdS NCs), likely due to enhanced surface availability. The TOC removal efficiency of MB for TGA-capped CdS aerogels after annealing reaches 41.5% after 2 h, indicating partial mineralization of MB into inorganic species.

Fig. 4.

(a) Photocatalytic degradation of MB (5.0 × 10 −5 M) in the absence and presence of a CdS catalyst (10 mg) under visible light irradiation. (b) Corresponding UV/Vis spectra at 3 h. The inset shows an MUA-capped CdS aerogel, floating on the surface of the aqueous MB solution

Powdered aerogels collected post-catalysis remain bright yellow in color, suggesting that the decolorization process is due to dye decomposition, and not absorption, as was found when attempting to use MUA-capped CdS nanoparticles. Indeed, based on UV/vis analysis, MB absorption by aerogels is minimal (ca 5% after 5 h in the dark). The fate of residual organics is further tested by IR. As shown in Fig. S4 (ESI†), the FTIR spectrum of MB (Fig. S4) shows complex vibrational modes due to the various organic functional groups (C-H stretch: 2852 and 2919 cm−1; C-N stretch: 1340–1355 cm−1; N-H bend: 1602 cm−1; C=N stretch: 1640 cm−1), whereas spectra of the CdS aerogels before and after photodegradation of MB are virtually identical, suggesting little or no absorption of organics is occurring during the photocatalytic process. This again suggests the decolorization is due to photocatalytic degradation rather than adsorption.

In order to test the stability of the CdS aerogels, two cycles of the MB degradation have been carried out using the same photocatalyst, and the MB decomposition rate for cycle 2 is virtually identical to cycle 1 (Fig. S5, ESI†). This, along with the IR data, bodes well for the recyclability of the materials, providing that the activity can be maintained long-term (i.e., the material is stable to photocorrosion). The consequences of photocorrosion in the use of CdS NCs, particularly those that are thiolate-capped, is aggregation and densification (i.e., the photoexcited “holes” are oxidizing the surface sulfide, resulting in interparticle disulfide bonds and irreversible assembly). As the aerogels are “pre-assembled”, they are not subject to this particular hole-trapping route, providing—at a minimum—a structural stability that is non-characteristic of the NC precursors. Moreover, based on photocurrent studies on related aerogel systems,29 we expect that the catalytic efficiency can be augmented by passivating remaining traps on the surface of the CdS NC aerogel, achieved by introduction of a passivating shell such as ZnS.

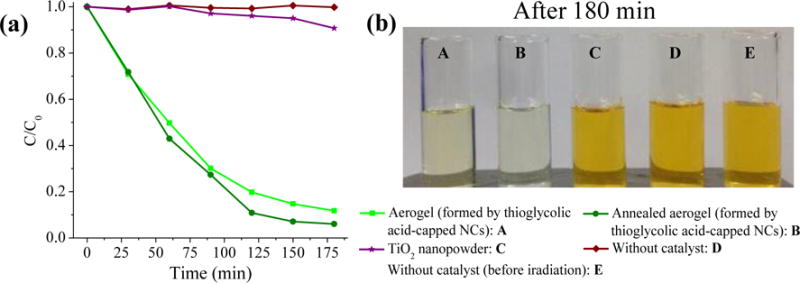

Finally, we studied the versatility of CdS aerogel materials (10 mg) for photocatalytic degradation of different dyes using MO (5.0 × 10 −5 M) and compared the catalytic performance with a TiO2 nanopowder (Strem chemicals, Surface area: ≥ 500 m2/g) as well. As expected, the TiO2 nanopowder showed lower catalytic activity under visible light irradiation due to the poor absorption of visible light (Fig. 5). In contrast, outstanding photocatalytic activities were exhibited by CdS aerogels formed from thioglycolic acid-capped NCs, as was the case for MB, and activity was further enhanced after heat treatment.

Fig. 5.

(a) Photocatalytic degradation of MO (5.0 × 10 −5 M) in the absence and presence of CdS catalysts or TiO2 nanopowder (10 mg) under visible light irradiation. (b) Photographs of MO solutions after visible light irradiation for three hours.

Conclusions

The applicability of CdS aerogel materials as visible-light-driven photocatalysts for degradation of organic dyes has been demonstrated using MB and MO as test molecules. Compared to ligand-capped CdS NCs, CdS aerogels showed enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation, attributed to the high surface area and better charge separation achieved by assembling discrete CdS NCs into a highly porous network using sol–gel methods. Furthermore, exchanging NCs with short-chain thiolate ligands before the gelation step leads to more efficient removal of surface ligands and a higher accessible surface area, which in turn results in better catalytic performance. Annealing also helps to further improve the performance in photocatalytic dye degradation, possibly as a consequence of strengthening the connectivity between discrete NCs in the porous network and removing more of the surface ligands. The synthesis of CdS aerogel materials as solid supports may provide a low cost and efficient method for remediation of organic effluents in wastewater. Future studies are focused on assessing long term stability and reuseability of the catalyst and probing the mechanism of degradation as well as the final fate of the dye molecules (molecular organic fragments vs. complete mineralization).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (R44 CA138013-03, via a subcontract from Weinberg Medical Physics, LLC) for partial funding in addition to Wayne State University for a A. Paul Schaap Faculty Scholar Award. Electron microscopy was acquired in the WSU Lumigen Instrument Center on a JEOL 2010 purchased under NSF Grant DMR-0216084.

Footnotes

Electronic Supporting Information available (ESI): High resolution TEM images of TOPO-capped NCs; UV-vis, PL spectra and PXRD patterns of CdS NCs and aerogels; photocatalytic data of MUA-capped CdS NCs and a photograph of the CdS post-catalytic product; FTIR spectra of catalyst before and after testing; recyclability test.

References

- 1.Kim S, Hwang SJ, Choi W. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:24260–24267. doi: 10.1021/jp055278y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klosek S, Raftery D. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:2815–2819. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan SUM, Al-Shahry M, Ingler WB. Science. 2002;297:2243–2245. doi: 10.1126/science.1075035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asahi R, Morikawa T, Ohwaki T, Aoki K, Taga Y. Science. 2001;293:269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1061051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cottineau T, Bealu N, Gross PA, Pronkin SN, Keller N, Savinova ER, Keller V. J Mater Chem A. 2013;1:2151–2160. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Xi J, Ji Z. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:17700–17708. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breault TM, Bartlett BM. J Phys Chem C. 2013;117:8611–8618. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apte SK, Garaje SN, Mane GP, Vinu A, Naik SD, Amalnerkar DP, Kale BB. Small. 2011;7:957–964. doi: 10.1002/smll.201002130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo Y, Wang J, Tao Z, Dong F, Wang K, Ma X, Yang P, Hu P, Xu Y, Yang L. CrystEngComm. 2012;14:1185–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo M, Liu Y, Hu J, Liu H, Li J. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2012;4:1813–1821. doi: 10.1021/am3000903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin G, Zheng J, Xu R. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:7363–7370. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang D, Li D, Guo L, Fu F, Zhang Z, Wei Q. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:5984–5990. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao WT, Yu SH, Liu SJ, Chen JP, Liu XM, Li FQ. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:11704–11710. doi: 10.1021/jp060164n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji KH, Jang DM, Cho YJ, Myung Y, Kim HS, Kim Y, Park J. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:19966–19972. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kannaiyan D, Kim E, Won N, Kim KW, Jang YH, Cha MA, Ryu DY, Kim S, Kim DH. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:677–682. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tak Y, Kim H, Lee D, Yong K. Chem Commun. 2008;0:4585–4587. doi: 10.1039/b810388g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang Z, Liu Y, Fan Y, Ni Y, Wei X, Tang K, Shen J, Chen Y. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:13968–13976. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen Z, Chen G, Yu Y, Wang Q, Zhou C, Hao L, Li Y, He L, Mu R. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:19646–19651. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghugal SG, Umak SS, Sasikala R. Appl Catal A: General. 2015;496:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banerjee A, Yuhas BD, Margulies EA, Zhang Y, Shim Y, Wasielewski MR, Kanatzidis MG. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2030–2034. doi: 10.1021/ja512491v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J, Kelley MS, Wu W, Banerjee A, Douvalis AP, Wu J, Zhang Y, Schatz GC, Kanatzidis MG. Proc National Acad Sci. 2016;113:5530–5535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605512113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shim Y, Yuhas BD, Dyar SM, Smeigh AL, Douvalis AP, Wasielewski MR, Kanatzidis MG. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:2330–2337. doi: 10.1021/ja311310k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuhas BD, Smeigh AL, Douvalis AP, Wasielewski MR, Kanatzidis MG. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:10353–10356. doi: 10.1021/ja303640s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuhas BD, Smeigh AL, Samuel APS, Shim Y, Bag S, Douvalis AP, Wasielewski MR, Kanatzidis MG. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7252–7255. doi: 10.1021/ja111275t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohanan JL, Arachchige IU, Brock SL. Science. 2005;307:397–400. doi: 10.1126/science.1106525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arachchige IU, Brock SL. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:801–809. doi: 10.1021/ar600028s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pala IR, Arachchige IU, Georgiev DG, Brock SL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:3661–3665. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Freitas JN, Korala L, Reynolds LX, Haque SA, Brock SL, Nogueira AF. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2012;14:15180–15184. doi: 10.1039/c2cp42998e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korala L, Wang Z, Liu Y, Maldonado S, Brock SL. ACS Nano. 2013;7:1215–1223. doi: 10.1021/nn304563j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng ZA, Peng X. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;123:183–184. doi: 10.1021/ja003633m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hines MA, Guyot-Sionnest P. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:468–471. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arachchige IU, Brock SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7964–7971. doi: 10.1021/ja061561e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu WW, Qu L, Guo W, Peng X. Chem Mater. 2003;15:2854–2860. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korala L, Brock SL. J Phys Chem C. 2012;116:17110–17117. doi: 10.1021/jp305378u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korala L, Li L, Brock SL. Chem Commun. 2012;48:8523–8525. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34188c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.