Abstract

The first phase of environmental health and safety of nanomaterials (nanoEHS) studies has been mainly focused on evidence-based investigations that probe the impact of nanoparticles, nanomaterials and nano-enabled products on biological and ecological systems. The integration of multiple disciplines, including colloidal science, nanomaterial science, chemistry, toxicology/immunology and environmental science, is necessary to understand the implications of nanotechnology for both human health and the environment. While strides have been made in connecting the physicochemical properties of nanomaterials with their hazard potential in tiered models, fundamental understanding of nano-biomolecular interactions and their implications for nanoEHS is largely absent from the literature. Research on nano-biomolecular interactions within the context of natural systems not only provides important clues for deciphering nanotoxicity and nanoparticle-induced pathology, but also presents vast new opportunities for screening beneficial material properties and designing greener products from bottom up. This review highlights new opportunities concerning nano-biomolecular interactions beyond the scope of toxicity.

Keywords: nanoEHS, toxicology, biocorona, extracellular polymeric substances, EPS, organism, response, protein, aggregation, computer simulations, statistical modelling

Graphical abstract

NanoEHS, a reflection

The birth of the nanoEHS (Environmental Health and Safety of Nanomaterials)1 field was originated by the concern on the unknown consequences of introducing engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) to the human body or the environment.2–5 It is a natural question to ask whether the very properties of ENMs being exploited in nano-related applications (such as high surface reactivity and ability of crossing biological barriers) might also have negative health and environmental impacts.2 In order to answer this question, the field took an initiative to develop assessment tools based on traditional chemical toxicology and was set to investigate the impacts of ENMs and nanotechnology from cradle-to-grave at a pace commensurate with the development of nanotechnology.6, 7 It was quickly recognized that the impact of ENMs on biological systems, positive or negative, hinges on biophysicochemical interactions at the nano-bio interface.8 In contrast to traditional chemicals, ENMs possess diverse physicochemical properties that require additional consideration in toxicity testing. The dynamic physicochemical properties of ENMs play a critical role in their fate and transport, human and environmental exposure conditions and hazard generation.1, 9 All of these aspects require extensive knowledge acquisition about the unique interactions between ENMs and various biological systems. Therefore, by nature, the path set forth for this field requires an integration of disciplines, including colloidal science, materials science, chemistry, biophysics, toxicology/immunology, and environmental science.1, 7, 10, 11

Because of the interest of discovering and the economic incentive of avoiding the hazardous effects of ENMs, this multidisciplinary enterprise of nanoEHS has been focused on toxicity assessment. A decade later, with a wealth of information accumulated on various types of ENMs and their hazard profiles obtained using tiered models, i.e. from cells to animals, we now reflect on the advances of this field, summarize the effective research approaches, and anticipate new research topics going forward. We envisage that the knowledge gathered and being pursued at the nano-bio interface will have the potential to invent new tools for treating human diseases as well as preventing environmental crises.

Predictive approach and toxicological paradigm

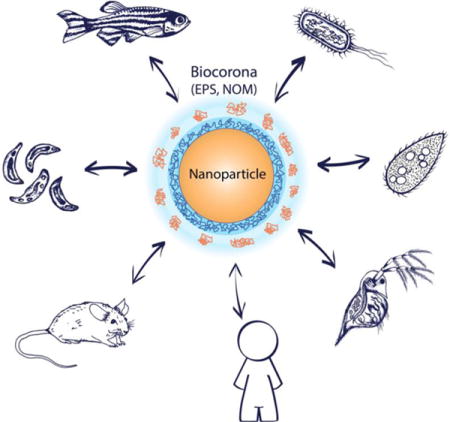

With the “nano” component of the nano-bio interface being defined as anything man-made and at least one dimension falling in the range of 1–100 nm, the “bio” component expands from proteins and cells to low-level organisms and vertebrates, and up to mammals and humans (Fig. 1). Considering the vast number of nano-bio interactions that could be generated when ENMs of different physicochemical properties such as composition, size, surface area, shape, aggregation/agglomeration, crystallinity and surface functionalization make contact with various biological entities, such as lipids, proteins, cell membranes, organelles, tissues and whole organisms, it is not possible to describe every aspect of nano-bio interactions.8 Knowing the conundrum of the chemical industry, where among more than half a million industrial chemicals invented and manufactured, fewer than a thousand of them have undergone toxicity testing, it was rational to invest in developing alternative testing strategies for ENMs. In agreement with the landmark 2007 report from the US National Academy of Sciences, “Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy”, tiered testing strategies based on predictive toxicology approach were implemented to examine nano-bio interactions at incremental levels, i.e. from cells to organisms.12 The rationale was that by using in vitro platforms (high-throughput screening, HTS), a variety of nano-bio interactions can be studied simultaneously in order to prioritize more detailed in vivo investigations.13, 14

Figure 1. A new frontier of research in nanoEHS.

Much fundamental science and their implications remain to be understood and exploited at the interface between ENMs and the biocorona, a dynamic layer of biomolecules adsorbed on the NP surface through self assembly, crowding and, at times, aggregation and fibrillation. It is important to understand that the passage and fate of NPs inside cells and tissues and across the barriers between different compartments, organs as well as species are consequential to the physicochemical and biological identities of the ever evolving biocorona.

To make such predictive approach valid and vital, translation and validation between in vitro and in vivo testing is essential. Along this direction, a few representative toxicological paradigms have emerged over the years.10, 13 For instance, in vitro assays have revealed the crucial role of the released of ions in the toxicity of certain metal and metal oxide based ENMs, e.g., Ag, CuO and ZnO NPs.15–22 The release of metal ions from NPs at nano-bio interface has been often linked to generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which set forth a series of cellular responses leading to oxidative injury and cell death.23, 15–20 These responses have also been observed in vivo, proving that in vitro assays can successfully predict toxicological pathways.24–28 For insoluble ENMs, bandgap structures and overlap of the conduction bands of ENMs with biological redox potential determine the generation of detrimental ROS.29 Among the surface properties of ENMs, surface charge and functionalization (e.g., PEGylated vs. bare particles) serve as main contributors to nano-bio interactions and subsequent toxicological outcomes.30 Membrane damage caused in in vitro experiments by cationic ENMs such as polystyrene NPs, liposomes, dendrimers, mesoporous silica, and carbon nanomaterials have been shown to translate to in vivo toxicological outcomes.31–36 Evidently, a comprehensive grasp of biological injury mechanisms originating from the nano-bio interface was the key for developing such predictive approaches. It is important to note that the aforementioned toxicological paradigms were mostly derived from empirical data and known toxicological pathways. With the advancements in proteomics and genomics-based approaches, it is likely that new toxicological paradigms will soon become available.37–40

High-throughput screening and the big data era

In order to provide discovery platforms with the ability to consider a wide range of nano-bio interactions, streamlining experimental procedures to reach HTS capacity has undergone development concurrently with the nanoEHS field. The benefit to implement HTS for nanoEHS research was consistent with the advocate for increased efficiency of toxicity testing by transitioning from qualitative, descriptive animal testing to quantitative, mechanistic, and pathway-based toxicity testing in cell lines.12

One in vitro HTS example that emerged was the study conducted by George et al. on a series of metal and metal oxide NPs.41 The in vitro HTS platform was established based on a cocktail of compatible fluorescent dyes to develop an epifluorescence-based approach that screened for a functionally connected series of oxidative stress related injury responses in mammalian cells. These fluorescent dyes were selected to avoid possible interactions between the NPs and the assay reagents that might yield false positives and negatives.42 This multi-parameter HTS assay, which was comprised of robotic handling of multitier plates, automated liquid handing and series of ENM dilutions, contemporaneously assessed total cell number and nuclear size, mitochondrial membrane potential, intracellular calcium flux, and increased membrane permeability based on microscopic images captured automatically. The functional link between the cellular responses measured by the cocktail of fluorescent dyes makes such platform suitable for assessing the biological effects of any ENMs with the potential of generating oxidative injury. The high-volume, image-rich, kinetic HTS data sets led to further development of machine-learning and hazard-ranking tools that are capable of establishing specific structure-activity relationships (SARs) of ENMs.43–46 Details on the statistical modelling will be discussed in a later section. Similarly, HTS platforms employing robotics, automated imaging and computer-assisted image analysis have also been established for algae, sea urchin and zebrafish embryos.47–50 It is also plausible that new HTS platforms for nanoEHS could be discovered based on proteomics and genomics-based approaches.51

Naturally, HTS has facilitated a smooth transition for the nanoEHS field to enter the big data era. Exploiting computational methods for assisting the establishment of quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSARs) and further enabling safer-by-design or risk reduction approaches will be discussed in the statistical modelling section.

The less explored: nano-bio interaction at the molecular level

With the aforementioned research approaches, nanoEHS field has made significant advances illustrating interactions at various nano-bio interfaces. While majority efforts have emphasized either the “nano” component of the nano-bio interactions (i.e. establishing relationships between the “nano” properties and the biological outcomes) or the biological consequences at cellular level and beyond (i.e. cytotoxicity, developmental disturbance, pathological outcomes in tissue culture and animal models), fundamental understanding of molecular-level nano-bio interactions, known generically as the protein corona or biocorona, remains less explored within the context of nanoEHS. While making connections between in vitro data and in vivo investigations, it is important to realize the differences between the simpler biocorona formed in in vitro assays and the much more complex protein-rich environment in in vivo testing.52 Moreover, since most ENM-cell interactions occur in a biomolecule-rich environment, it is important to recognize the formation of biocorona as inevitable simply for the argument of energetics. Understanding the identity and formation kinetics of biocorona in association with the physicochemical properties of ENMs is not only the key to deciphering the molecular mechanisms of NP-induced adverse effects but also presents vast opportunities to exploit the biocorona.53, 54 In the following sections we review research on the role of NP-biomolecular interactions in nanomaterial toxicity, and discuss experimental, statistical modelling and computer simulation strategies capable of revealing the inner workings and nanoEHS implications of the biocorona. An outlook of this new frontier is presented at the end of the review.

NP-biomolecular interactions in nanotoxicology, a frontier

The importance of defining the key properties that drive the toxicity of ENMs has been long emphasized both in human and environmental toxicology.8, 13 The central role of the biocorona – a dynamic layer of biomolecules adsorbed on the NP surface – in cell interactions and subsequent biological effects has been recognized in biomedical applications of ENMs, as highlighted by several excellent reviews.55–57 Recently, understanding the interplay between biomolecules and ENMs in environmental toxicity testing has been brought into focus.58

NP toxicity influenced by laboratory test media

The role of the chemical composition of exposure media in the toxicity of ENMs has been acknowledged from early on. In 2006, Zhu et al.59 reported a stimulatory effect on the growth of protozoan Tetrahymena pyriformis when cultured with multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) in proteose peptone yeast extract medium. This effect was attributed to the noncovalent binding of peptone with MWCNTs that facilitated cell entry of peptone by phagocytosis. In contrast, growth inhibition was observed when the protozoa were exposed to MWCNTs in filtered pond water. Other authors have also reported that high ionic strength or organics-rich media influence the agglomeration pattern of NPs, through modifying the surface chemistry of ENMs that often results in reduction of NP number and concentration, and consequently decrease of NP-cell contact and NP-specific toxicity.60, 61 In the case of soluble metal-based NPs (e.g. CuO, ZnO, Ag, Fe3O4 and CdSe), medium composition and biocorona formation strongly influence the extent of dissolution, speciation and bioavailability of dissolved metal ions. Kakinen et al.62 compared 17 different test media for CuO NP speciation and bioavailability and concluded that dispersion of CuO NPs in the medium containing high concentrations of organic compounds resulted in enhanced dissolution of copper, due to increased dispersion of CuO NPs and complexation of copper ions with the organic compounds. These simultaneous processes influenced the level of bioavailable copper and consequently nanotoxicity, compared to that in media with little to no organic compounds. Thus, biocorona formation by organic compounds is an important factor that can influence the toxicity of NPs and should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results of toxicity tests.

NP toxicity influenced by natural organic matter (NOM)

To assess and predict NP behaviour in natural waters and soils, instead of conventional laboratory test media, experiments are conducted in more environmentally relevant conditions. Such test designs often include NOM which is a complex mixture of organic compounds originating from the decomposition of plant and animal residues, soluble microbial products, and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS).63, 64 NOM is composed of nonhumic (polysaccharides, lignin, proteins, and polypeptides) and humic substances (high-molecular-weight microbial degradation products of plant material). Since the major acidic functional groups in NOM, carboxyl and phenolic groups, deprotonate at pH > 3, NOM is negatively charged in soils and natural waters. Due to high adsorption affinity of NOM for mineral surfaces and π-π stacking on hydrophobic ENMs, coupled with its environmental relevance, NOM is often used as a dispersing and stabilizing agent of NPs in the aqueous phase.65–67 Furthermore, due to increased dispersability or alternation in the polarity of ENMs, NOM-coating has been shown to modify NP toxicity. For instance, humic acid mitigated the toxicity of MWCNTs to unicellular green alga Chlorella pyrenoidosa68 and decreased the uptake of fullerene (nC60) in D. magna and zebrafish.69 In other studies, NOM-coated MWCNTs proved more toxic to daphnids70 and a freshwater diatom71 than their pristine counterparts. NOM coating on NP surface has been shown to exert cell type-specific uptake and damage: NOM-coated fullerene entered mammalian cells more readily than plant cells.65 The latter was explained by the hydrophobic nature of NOM-coated NPs that facilitated partitioning into mammalian cell membranes but were excluded by plant cell walls. However, NOM does not solely govern the uptake of ENMs to cells and organisms: in a study with rice plants NOM-coated C70 was taken up by plants and translocated through plant tissues while NOM-covered MWCNTs were merely adsorbed to the plant roots.66 In the case of spherical metal NPs with well-defined size and shape, it is well known that surface charge is one of the main determinants of NP uptake and translocation in plants with positively charged NPs most readily taken up by plant roots.72 Since NOM-coating renders NPs negatively charged, the reduced toxicity and accumulation of NOM-coated NPs in plants is often attributed to hindered interaction between NPs and negatively charged plant root surfaces.73–76 While in the latter studies NP exposure was conducted in defined hydroponic conditions, others have explored NP effects on plants and rhizosphere in more complex mesocosms consisting of NP-amended soil and organisms. Ge et al.77 showed that plant root system significantly influenced NP effects on soil bacterial communities. The study revealed the complex nature of NP interactions in planted versus unplanted soil systems: plant growth ameliorated ZnO NP toxicity but promoted the impact of CeO2 NPs on bacterial communities, possibly by changing the belowground biogeochemistry. Living organisms are known to secrete extracellular compounds during their life cycle to facilitate nutrient uptake, intercellular communication, cell migration and other functions. EPS produced by microorganisms78 and composed mainly of polysaccharides and proteins constitute an important fraction of NOM and thus have been studied for their effects on NP stability and toxicity. Compared to total NOM, EPS has been shown to improve the stability of NPs to a greater extent, including reduced aggregation of single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs)79 and copper-based NPs.80 Improved dispersion of EPS over NOM may be a result of preferential adsorption of protein-like components over humic substances, as demonstrated for graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide.81 Increased residence times of EPS-dispersed ENMs in the water column could pose a higher risk to pelagic organisms through extended NP exposure. EPS can also mediate increased dissolution of metal-based NPs or leaching of metal catalysts from carbon nanomaterials to impact bioavailability.79, 80 Other biomolecules that have been shown to disperse and disaggregate NPs through biocorona formation include alginate,82, 83 bovine serum albumin (BSA)84 and monosaccharides.85

The physicochemical characteristics of NPs in the environmental matrices can also be influenced by direct particle-cell contacts that may result in NP-microorganism hetero-agglomerate formation or changed dispersion pattern of NPs. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a Gram-negative bacterium, was shown to mediate the dispersion of TiO2 NP homo-agglomerates by preferential adsorption of the NPs to bacterial cells, highlighting the role of bacteria in enhancing NP mobility in the environment.86 In contrast, D. magna reduced the stability of carbon nanotubes in freshwater, likely by digesting the nanotube biocorona.87 Biomodification of NPs both by NOM and direct cell or organism contact is an important factor that influences the environmental fate and toxicity of ENMs.

Mitigation of NP toxicity by biocorona/extracellular substances

Biocorona formation generally renders NPs stably dispersed in the aqueous phase, potentially increasing NP contacts with cells and organisms that has been shown to enhance nanotoxicity.88, 89 However, EPS produced by cells can act as a potent mitigator of nanotoxicity as reported by many studies. NOM-dispersed MWCNTs were shown to have strong affinity for EPS secreted by freshwater diatom Nitzschia palea, which was proposed as a protective mechanism against MWCNT toxicity.71 Similarly, the role of EPS in mitigating TiO2 NP toxicity has been reported in cyanobacteria – EPS-depleted mutant strain was more susceptible to NPs than the wild type.90 Chemically inert TiO2 NPs can become highly reactive under ultraviolet light and exert toxicity through ROS generation. Since ROS are generally short-lived, NPs have to be in close vicinity to the cell to exert ROS-mediated toxicity. This is likely the reason why extracellular compounds secreted by cells act as a protective layer by consuming harmful ROS.90 The role of extracellular substances in regulating the biological effects of soluble metal NPs has also been extensively studied. Chen et al.91 showed that cell damage induced by ZnO NPs to freshwater algae Chlorella sp. was counteracted by algal exudates that coated positively charged NPs through electrostatic interaction and hydrogen bonding as well as complexed harmful Zn2+ ions. In addition, ZnO NPs were extensively agglomerated in the presence of algae, resulting in reduced dissolution of NPs. Similar mechanisms for mitigation of AgNP toxicity by algal extracellular dissolved organic carbon (DOC) compounds were proposed.92 Namely, freshwater alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii was considerably less sensitive to AgNPs in the late growth phases when extracellular DOC levels were high, compared to cells in early growth phases. It was proposed that algal exudates reduced AgNP toxicity by forming AgNP agglomerates, complexing toxic Ag+ ions, limiting particle-cell interactions and acting as a sink for NP-generated ROS. The protective role of EPS against AgNP toxicity also in bacterial biofilms was recently reported.93 In the marine diatom Thalassiosira weissflogii the toxicity of AgNPs was caused solely by Ag+ ions, whereas the toxicity was mitigated by increased EPS production in response to Ag+ ions and subsequent complexing of toxic metal ions and ROS by EPS.94 Increase in EPS production has also been reported in freshwater alga Chlorella pyrenoidosa upon exposure to CuO NPs that generated ROS and caused mitochondrial depolarization in alga through Cu2+ ions, indicating a possible cellular protective mechanism of EPS.95 The influence of EPS on the physicochemical properties of CeO2 and AgNPs was recently studied by Kroll et al.,96 who used EPS extracted from periphyton with varying composition to study changes in particle size and solubility upon incubation in EPS; EPS was found to stabilize CeO2 NPs and reduce their solubility. However, AgNPs increased in size in EPS, both at single particle level and through agglomeration. Increase in particle size was counterintuitively accompanied by higher dissolution of AgNPs. It was concluded that simultaneous oxidation of AgNPs and reduction of Ag+ occurred in the system, whereas EPS components, specifically polysaccharides with their hydroxyl and hemiacetal groups, contributed to the reduction of Ag+ to Ag0 at the surface of AgNPs that increased in size. The role of hemiacetal groups of sugars in reducing Ag+ in bacterial EPS was also reported by Kang et al.97 Reduction of Ag+ to less potent AgNPs by Escherichia coli EPS was interpreted as a mechanism for mitigating the antibacterial activity of silver. Such detoxification strategies are not confined to prokaryotic microorganisms. Juganson et al.98 showed that the extracellular soluble fraction of protozoa Tetrahymena thermophila contained potent Ag+-reducing substances that contributed to the formation of AgNPs – less toxic form of silver to protozoa – from AgNO3. While the carbohydrates of EPS might be responsible for the reduction of Ag+ to metallic silver, soluble proteins were shown to play a role in the formation and stabilization of AgNPs by rendering a protein corona on the NPs. The contributions of both proteins and carbohydrates in the formation of biogenic NPs were recently confirmed also in the case of selenium NPs synthesized in the EPS of anaerobic granular sludge.99 The functional groups of the EPS were shown to govern the surface charge of the NPs, thus influencing their fate in the environment. AgNPs readily interacted with proteins in the biological media resulting in a protein corona on the NP surface. These interactions may interfere with the activity of catalytic proteins, most likely through the release of Ag+ ions that reacted with the cysteine residues and N-groups of the enzyme to impair the enzymatic activity.100 On the other hand, formation of protein corona has been demonstrated to reduce nanotoxicity to certain human cells. For instance, binding of a blood protein – bovine fibrinogen – rendered SWCNTs less harmful to human acute monocytic leukemia cell line and human umbilical vein endothelial cells.101 Considering protein corona, and biocorona in general, there is a growing body of literature covering the role of NP biocorona in inducing physiological, including immunological, responses in mammalian organisms.102, 103 However, studies that report organismal defence mechanisms to NOM-, EPS- or biomacromolecule-coated NPs in environmentally relevant organisms are rare. Recently, NP-protein corona formation was characterized in the hemolymph serum of the marine bivalve Mytilus galloprovincialis.104 The study indicated that protein-covered polystyrene NPs induced higher levels of cell damage and ROS production than pristine polystyrene NPs. Higher toxicity of NPs with biocorona was attributed to dysregulation of immune response. On the other hand, another study in plants found that tannic acid coating reduced the toxicity of neodymium oxide NPs to pumpkin by boosting superoxide dismutase and catalase activity to harness excessive ROS.73 Overall, there is a knowledge gap on mechanistic understanding of how biocorona formation influences NP physiological effects in environmentally relevant species.

NP effects on release and structure of specific extracellular substances

At sublethal concentrations, ENMs are known to modulate the expression and synthesis of specific compounds secreted by microorganisms. For instance, ZnO NPs were shown to inhibit biofilm formation and production of pyocyanine, a virulence factor, in P. aeruginosa.105 Gene expression analysis revealed upregulation of genes involved in zinc cation efflux pump functioning and repression of pyocyanine-related operon. In an earlier study Dimkpa et al.106 showed that in a soil-beneficial bacterium P. chlororaphis ZnO NPs inhibited the synthesis of another virulence factor, pyoverdine, mainly through dissolved zinc ions. In contrast, CuO NP-induced inhibition of the same biomolecule synthesis was found to be nano-specific.106, 107 In addition to being a virulence factor, pyoverdine functions as an iron-chelating compound that numerous bacteria secrete to acquire iron from the surrounding medium. Interestingly, according to Avellan et al.,108 bacterial siderophores were capable of chelating iron ions also from iron-doped germanium-imogolite nanotube structures while the secreted biomolecules promoted biodegradation of the nanotubes. This study suggests that metabolic response to certain components of an ENM may also induce biodegradation of the ENM. Besides metal-based ENMs, sublethal concentrations of SWCNTs have been shown to inhibit the production of pyoverdine by P. aeruginosa,109 at both physiological and gene transcriptional levels. These studies underline the impacts of ENMs on microbial physiology and cell-cell interactions through EPS synthesis. Yet, molecular information concerning the composition, conformation, evolution and implications of such NP-biomolecule interactions remains to be elucidated.

Nanoparticle-biocorona – experimental strategies

Major techniques

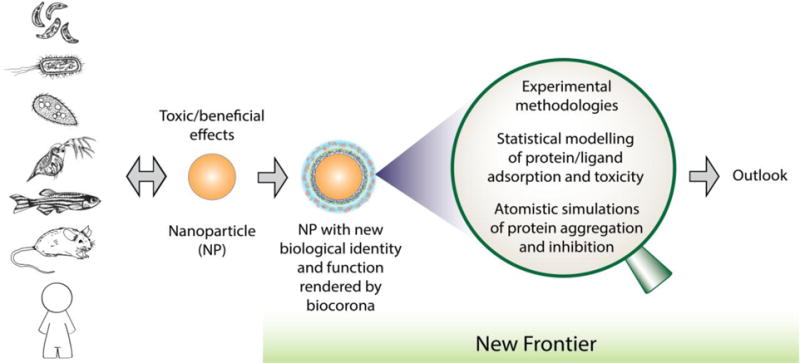

A host of biophysical and analytical methodologies are available for quantifying and determining protein species adsorbed on NPs, for the applications of nanotoxicology, nanomedicine and nanobiotechnology110, 111. Despite differences in subject and – potentially – dosage, many of these methodologies and protocols may be utilized for examining biocoronae secreted by environmental organisms upon ENM exposure (Table 1). A survey of literature shows that UV-Vis spectrophotometry, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and sodium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE (SDS-PAGE), size exclusion chromatography (SEC), differential centrifugal sedimentation (DCS) and the highly sensitive proteomic mass spectroscopy (MS) are some commonly used techniques for separating protein species among themselves and from NPs and for identifying and quantifying protein compositions within a corona.89, 112–121 For imaging, transmission electron microscopy (TEM; resolution: 0.1–0.5 nm), atomic force microscopy (AFM; vertical resolution: 0.1 nm) (Fig. 2A, B) and confocal fluorescence microscopy (resolution: ~350 nm) can reveal information of soft and hard coronae on NP surfaces in either dehydrated or aqueous phase, and often down to single NP level for TEM and AFM.122–126 Dynamic light scattering (DLS; detection range: 0.3 nm–10 μm) and synchrotron-based techniques such as small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) (Fig. 2C), and wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) can yield information about the hydrodynamic size, polydispersity index, structure, morphology and crystallinity of NPs and polymeric materials (including proteins) on the mesoscopic scale.110, 125, 127 Shifts in frequency and amplitude of surface plasmon resonance (SPR; affinity range: fM to mM) may render association and dissociation constants of protein-NP binding where the NPs are immobilized on a gold-coated substrate.112 Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) quantifies binding affinity, stoichiometry, and thermodynamic parameters of proteins interacting with NPs.113, 122 Hyperspectral imaging, a dark-field microscopy technique, is suited for semi-quantification of protein adsorption onto metal NPs, with or without the presence of cells or organisms.128, 129 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) measures the absorbance of multi-wavelength light to infer interactions and bond formation between proteins and NPs.91 Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy resolves changes to the secondary structure of proteins and peptides upon binding to NPs.130, 131 Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (for proteins < 70 kDa) and X-ray crystallography (resolution: 1–5 Å, for small to arbitrarily large proteins) can reveal the 3-D structure, conformational dynamics, reaction rate, and chemical environment of proteins as well as proteins or ligands associated with NPs.110 Raman spectroscopy (resolution: sub-μm laterally and μm longitudinally) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; detection limit: ~100 ppm, for top sample surface), techniques commonly used for elemental analysis and surface science, may find ample use in the study of intricate and adaptive relationships between NPs, the biocorona as well as hosting cells and organisms.110, 111 In addition, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA; resolution: ~1 mg), an ensemble technique commonly used for determining selected characteristics of materials that exhibit either loss or gain in mass due to decomposition, oxidation, or loss of volatiles, should find use in quantifying the biocorona adsorbed on NPs of large quantities (> 1 mg) as well as mass loss of NPs themselves due to biodegradation.132

Table 1.

List of major experimental methodologies for the study of biocorona.

| Methodologies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction | Visualization | Structure | Composition |

| Isotherm, affinity, stoichiometry, thermodynamic properties | Morphology, crystallinity, dynamics | ||

| UV-Vis spectrophotometry | Transmission electron microscopy | Circular dichroism | Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| Dynamic light scattering | Scanning electron microscopy | Nuclear magnetic resonance | Size exclusion chromatography |

| Surface plasmon resonance | Atomic force microscopy | Small-angle X-ray scattering | Mass spectroscopy |

| Isothermal titration calorimetry | Confocal fluorescence microscopy | Small-angle neutron scattering | Differential centrifugal sedimentation |

| Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy | Hyperspectral imaging | Wide-angle X-ray scattering | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| Thermogravimetric analysis | X-ray crystallography | Raman spectroscopy | |

| Differential scanning fluorometry | |||

Figure 2. Exemplified characterizations of protein aggregation and NP-biocorona interactions.

A: TEM imaging of AgNP-luciferase corona.100 B: AFM phase imaging of ILQINS helical ribbons. C: SAXS spectra showing the formation of microcrystals converted from ILQINS helical ribbons.125 D: ICP-MS quantification of Zn ion release upon ZnO-algae interactions. Inset: SEM image of algal cells adsorbed with aggregates of ZnO NPs.91 E: Quantifying and analysing the transformation of NPs in a cellular environment using hyperspectral imaging.129 F: high throughput DLS measuring the aggregation of human islet polypeptide over time.126 G: principle of DSF, where Tm represents the melting temperature of the protein and ΔT dFenotes the temperature range of the protein undergoing a transition from molten to aggregated state.137 H: ATR-FTIR spectra showing the binding of ZnO NPs and algal exudates.91

Limitations

The complex composition (i.e., proteins, lipids, fatty acids, NOM, etc.) and cell/organism-dependent nature of the biocorona require extra care in their characterization. While increases in the beta sheet content as a result of protein aggregation are often characterized by the fluorescence-based thioflavin T and Congo red assays,133, 134 these methods remain to be validated for dealing with heterogeneous proteinous substances as is the case with the biocorona. SPR is effective in extracting the rates of binding between proteins and NPs, but its applicability for heterogeneous and complex protein samples has yet to be developed for targeting environmental biocoronae. CD spectroscopy reports changes in protein secondary structure at the ensemble level (~0.1 mg/mL, for 1 mm cells), and would require rigorous controls to extract such information for the protein species of interest within the entity of the biocorona. ITC is designed to measure minute thermal exchanges between small ligands and macromolecules of ~10–500 μM and, although rewarding in thermodynamic data collection, remains a challenge for characterizing highly heterogeneous biocorona (multiple species and molecular weights) and NPs (non-uniform size, shape and surface coating). With proper sample preparation and staining TEM can resolve both the presence and thickness of the biocorona on NPs. Cryo-TEM, specifically, is suitable for examining soft biocorona weakly associated with NPs, cells or organisms as dehydration could alter or eliminate such affinity if mediated via hydrogen bonding, van der Waals force or hydrophobic interaction. X-ray crystallography is a highly specialized, laborious and expensive technique for the characterization of specific materials that form crystals in specific solvents. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM; resolution: ~10 nm)91 (Fig. 2D, inset) equipped with elemental analysis is appropriate for imaging the biocoronae associated with cells or organisms, as electrons reflected off the surfaces of cells and organisms interfere to render three dimensional-like topologies.

Potential

Hyperspectral imaging is a technique which has attracted increased attention recently within the field of nanoEHS (Fig. 2E). The principle of dark-field imaging entails that such technique is suitable for examining metal and metal oxide NPs with or without the coating of biocorona, as proteinous substances alter the dielectric constant and hence SPR of the NPs in amplitude and/or peak wavelength. When incorporated with a scanner along the optical axis – a newly developed feature among such systems – hyperspectral imaging is suited for screening the adsorption, uptake and intracellular distribution of NPs, especially for vacuoles, cells, tissues as well as small organisms such as bacteria, algae, protozoa, and daphnids. This sectioning feature resembles that of confocal microscopy, albeit with lower spatial resolution due to the diffraction limit along the optical axis without a pinhole. However, laborious calibrations of nano- and biomaterials to establish spectral references128, 129 are a prerequisite of implementing data analysis for each nano-bio system under study.

UV-Vis spectrophotometry is a common but often overlooked technique for quantifying protein concentration as well as protein-protein and protein-NP interactions. This method can be subsequently plugged into the Freundlich isotherm to derive multiple-layer adsorption of an adsorbate (i.e. biocorona) onto a rough adsorbent surface with multiple binding sites (i.e. NPs, cells or organisms). Based on this principle Lin et al. and Bhattacharya et al. examined the inhibitive effects of styrene nanoplastic and CdSe/ZnS quantum dots on the photosynthetic properties of freshwater algae Chlorella, freshwater/saltwater Scenedesmus and Chlamydomonas sp., respectively.89, 135

The use of DLS for the quantification of the size and uniformity of NPs has become a standard practice in nanoEHS over the past decade. Recently, Wang et al. experimented the use of high throughput DLS for characterizing the binding of branched polyethyleneimine-coated silver NPs (bAgNPs) with cationic lysozyme and anionic alpha lactalbumin (aLact).136 With 384-well plates this technique was capable of resolving the continuously changing hydrodynamic sizes of bAgNPs exposed to the protein species of a range of concentrations over 24 h, consuming merely 6 μL of each sample volume. Furthermore, the samples were heated and then cooled at a pace of 0.52 °C/min via a temperature control module, displaying a remarkable hysteresis in the hydrodynamic size of lysozyme-bAgNP complexation versus temperature to reveal the intricate thermostability of the nano-bio system. This facile and high throughput technique (Fig. 2F)126 may find its use for characterising ENMs and the biocorona, allowing many different sample conditions to be monitored simultaneously and continuously at different pH, temperature, ionic strength/hardness of freshwater and salt water.

Another high throughput technique which we recommend for analysing the biocorona is differential scanning fluorometry (DSF), a fluorescence-based thermal shift assay which employs a hydrophobic fluorophore such as Sypro Orange and multiwell plates (Fig. 2G).137 As a result of unfolding at increased temperatures the hydrophobic core of a molten protein of interest becomes exposed to the external environment. Consequently, the fluorophore binds to the protein core and, upon excitation, gives rise to fluorescence that is otherwise quenched by the aqueous solution. Further increases in temperature cause the proteins to form aggregates through intermolecular hydrophobic interactions, which in turn discourages incorporation of the fluorophore into the proteins to gradually cease fluorescence. Using this technique Chen et al. uncovered the contrasting effects of fullerol C60(OH)20 on the thermal stability of lysozyme and immunoglobulin G (IgG) at different stoichiometric ratios, and attributed that to the physicochemical properties of the proteins as well as the duality of fullerol as both a particle and a chemical.137 Such duality originates from the limited solubility and finite size of ENMs and may have profound implications on the configuration and stability of the biocorona as well as the toxicity and fate of NPs in the environment.

Combined use of different analytical techniques can prove synergic for examining NP-biocorona and cell/organism-biocorona interactions. For example, Chen et al. applied the techniques of SEM, inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS), membrane potential and viability assays, as well as attenuated total reflectance (ATR)-FTIR to illustrate the adaptive interactions between freshwater algae Chlorella sp. and ZnO NPs (Fig. 2D, H), including agglomeration of algae to reduce their surface area upon NP exposure, secretion of algal exudates to cause aggregation and consequently reduced ion release and toxicity of the NPs, and formation of new bonds between algal exudates and the ZnO NPs.91 This approach may be extrapolated for assessing the interactions between other classes of aquatic organisms and metal oxide NPs, which will help establish a full database for mitigating environmental release of discharged ENMs.

Focusing on biocorona – a perspective from statistical modelling

Statistical modelling in nanoEHS

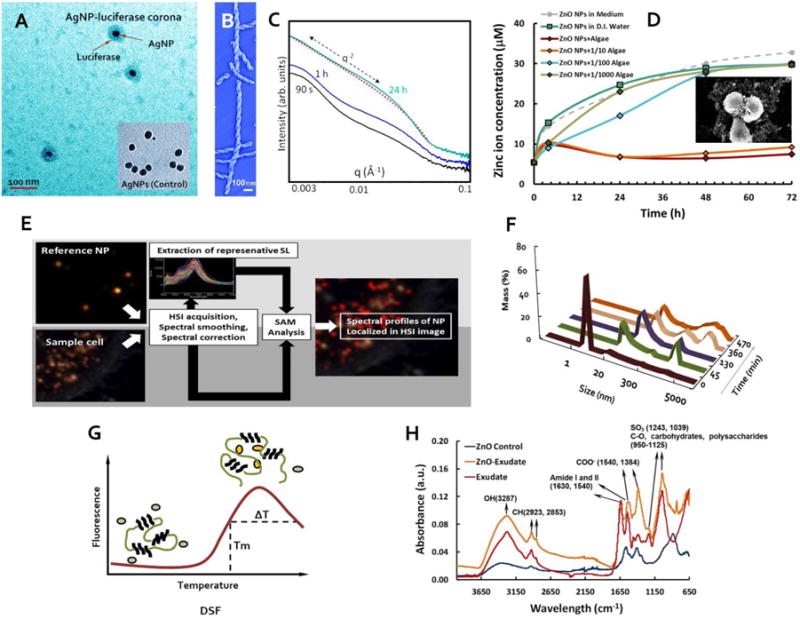

The application of statistical modelling in the nanoEHS field was made possible with the advancement of HTS and characterization technologies and instrumentation, as well as considerable amount of data from active experimental research accumulated in the past decade. The biological activities or environmental effects of ENMs are considered dependent upon the intrinsic physicochemical properties of the ENMs. However, depending on experimental methods, host systems settings, and potential reactants, those properties or attributes of ENMs can make up a large matrix. It is sometimes difficult to correlate property matrices obtained from materials characterization with observed biological or environmental effects or outcomes in a sensible way and make interpretations or predictions accordingly. Statistical processing and modelling of the data allows determination of the relationships between material properties as inputs, and resulting effects as outputs in a quantitative and predictive manner (Fig. 3). Based on such principles, a statistical modelling approach, known as QSAR,138, 139 can be constructed using parameterized quantitative property descriptors to predict biological or environmental interactions with various species from the host systems.

Figure 3. Schematic of statistical modelling for nanoEHS research.

Experimental data obtained from physicochemical interactions with biological or organic molecules, as well as biological effects of nanomaterials can be collected and curated as a large database. Statistical modelling can be built to characterize the surface physicochemical properties of nanomaterials and explore how they govern the interactions with surrounding molecules. Statistical learning methods are employed for both predictive modelling and classifications based on either surface properties or biological effect profiles.

As an important implementation of supervised statistical learning in nanoEHS, QSAR algorithms learns from actual experimental data, constructs predictive models utilizing large sets of experimental data as a training set, and chooses the most relevant parameters based on a given model form and statistical criteria such as goodness-of-fit and cross validation. Thus the parameter coefficients can be calculated, while predictions and comparisons for the sets that are not included in the training set can be made. In this process, information on determinative ENM properties can be extracted by evaluating the weight of each parameter represented by the coefficients.140 The specific field of application depends on the type of data used for training, as well as model structure. For example, linear solvation energy relationship (LSER) linearly relates the solvation energy parameters of a given chemical or nanomaterial to a certain activity, typically partition between two media such as adsorption. LSER is often used to find the determining properties of ENMs in organic toxicant adsorption for environmental applications.141, 142 Applying supervised statistical learning on discrete data generates classification models that can provide estimations on categorical or nominal outcomes. One of the most widely used classification algorithms, Support Vector Machine (SVM), adopts a classifier, and adjusts the flexibility of it to reach an optimized point based on the training data, to ensure that the virtual distance from each data point of different categories to the classifier in the abstract data space reaches maximum.143, 144 For example, since genotoxic materials can cause cancer, statistical classification modelling on genotoxicity data sets of a given group of chemicals can be used to determine the possibility of a given material to be carcinogenic.145 SVM has been adopted for pattern recognition in discriminating potential drug chemicals based on their induced biological responses146, 147 and should find use in describing the relationship between biocorona and the fate of cells and organisms upon ENM exposure.

Unsupervised statistical learning methods, such as clustering, have also been adopted to analyse the nanoEHS data. Clustering techniques are often capable of extracting information from input data that are unlabelled or without expected outcome. For example, a hierarchical clustering was used to analyse data of protein associations with gold and silver NPs.116 This technique can identify latent similarities among the NPs based on their protein fingerprints and then group them hierarchically. This process does not require a known classification of the NPs, but rather creates a categorization based on their similarities in terms of protein binding. Unsupervised statistical learning could prove advantageous when dealing with heterogeneous biocoronae secreted by multiple cell or organism species exposed to one or more types of ENMs.

Statistical modelling on physicochemical interactions

Characterisation and prediction of physicochemical interactions between ENMs and various organic or biological species in the host system, especially surface adsorption or the formation of biocorona, is a major effort in the nanoEHS applications of statistical modelling. These interactions are typically governed by various fundamental physicochemical forces whose ensemble effects can usually be determined experimentally, while individual forces of different origins often cannot be distinguished.148–150 QSAR has been shown as a successful implementation of statistical modelling connecting structures of chemical species to their environmental and biological effects, including drug design, pharmacokinetics, toxicology, medicinal chemistry,151–156 as well as analytical and physical chemical studies.153, 157–159 To determine surface physicochemical interactions, LSER, as an implementation of QSAR, is often adopted, based on the assumption that surface binding is linearly correlated with several parameterized physical forces that likely participate in the process. For example, in a proposed biological surface adsorption index (BSAI) approach, Abraham’s solvatochromic descriptors that parameterize interactions arising from lone-pair electrons, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic force, and hydrophobic force have been used to characterize surface adsorption of environmentally relevant organic pollutant molecules to porous carbon materials, as well as metallic or metal oxide ENMs.140, 160–162 Specifically, the binding coefficients are obtained experimentally from a set of organic molecules with varying chemical properties, then multivariate linear regression algorithm is used to generate the coefficients for each descriptor. Since model building based on these descriptors is essentially a supervised statistical learning process, the molecules used to obtain experimental data for the training of the model need to expand a reasonably large chemical space, in order to ensure the applicability of the resulted model for the prediction of molecules that are not included in the training sets. For interactions that may involve nonlinear processes, such as crowding of biocorona on a NP surface over time or competitive binding of multiple solute species, artificial neural networks (ANN) could be an ideal method to reveal latent relations between the predictors and the outcome, since ANN adopts nonlinear functions within one or more hidden layers between input data and output coefficients. For example, compared to linear regression, the prediction capability of surface binding of organic pesticides onto NP surfaces was improved using ANN.162

In addition to prediction, the modelling results can also be used to evaluate the surface properties of ENMs, since the coefficients represent the likeliness of each physicochemical force to participate in the interaction.163 Therefore, the model could potentially provide some insights on how ENM surfaces interact with biomacromolecules. The advantage of using solvatochromic parameters in modelling is that they can be easily related to physicochemical interactions and thus are ready for physical interpretations. However, for the purpose of prediction, other parameters are available, e.g., one study compared molecular connectivity based indices to solvatochromic parameters based LFER models, and vindicated the former as of higher predictive capability.164 In addition, comparing BSAI predicted values with results from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations could help validate the molecular models used in the simulations, which in turn can be applied for prediction without experimental data.165

Statistical modelling on biological effects

As aforementioned, statistical modelling often employs machine learning algorithms and its application largely depends on the data to be learned from. Similarly, QSAR can be used for the evaluation of in vitro biological effects of ENMs using high throughput cell-based techniques. Similar statistical learning algorithms can be employed to study the correlation between ENM surface physicochemical properties and biological effects, including cell uptake,166 cytotoxicity,167–169 and embryonic toxicity.170 In these studies, both experimentally measured properties such as size distribution, relaxivity (for magnetic materials), zeta potential167 and even quantum mechanical descriptors such as band gaps168 for semiconductors, and calculated molecular descriptors including molecular weight, geometric parameters, acidity/basicity and lipophilic index167 were used as variables in respective statistical models. The quantum mechanical descriptors are important because they are especially relevant in determining redox reactions and ROS generation in biological systems.

By and large, the selection of these descriptor needs to reflect the roles played by their respective physicochemical properties. Typically, a large number of initial descriptor should be included, then the number can be algorithmically reduced by fitting the data. For example, Chau et al. initially introduced 679 descriptors, then reduced those to 367 by determining the redundancy and removing the irrelevant ones. One simple way of achieving this is through stepwise regression, which iteratively adds and removes descriptors into and from the model regression to find an optimal combination based on statistical criteria.161

Although multivariate linear model is still widely used for the prediction of biological effects,168, 171–173 due to the significant nonlinearity in biological systems more often nonlinear algorithms166 are used. Logistic regression, SVM, k-nearest neighbours (kNN)166 and partial least squares (PLS)174 are usually used for classification. Association rule learning, which discovers regularities in large-scale data and generates data-drive hypothesis, was used to learn cellular responses induced by ZnO NPs.175 These classification techniques are typically used when nominal or categorical outcomes are desired in describing the biological or environmental effects, such as predictions of NPs being toxic vs. non-toxic or carcinogenic vs. non-carcinogenic. For characterizations of biocorona formation, supervised learning algorithms including these classification methods can categorise ENMs or biomolecules based on whether these molecules are present in the corona.

An emerging modelling approach is to use biological ‘fingerprints’ of a certain ENM, instead of direct physicochemical parameters, as variables for predicting how the ENM could interact with larger biological systems. Similar to the application of QSAR in determining the physicochemical interactions by using organic molecules as probes, biomacromolecules, such as proteins, are used as probes.116 The protein profile in a biocorona that forms on a NP surface is regarded as a set of fingerprints that describes how the surface of the NP interacts with biological components. These relative abundances from the profile are then used as predictors in a log-linear model to form a correlation with cellular association of the NPs. Subsequently, redundancy in the descriptors can be reduced by running the model through predictor selection algorithms. Closely associated with experimental data, statistical models are anticipated to be broadly applicable for the different aspects of nanoEHS, while specific applications of the models depend on the type of data. Hence, by incorporating various nano-bio or nano-environmental data, such as surface binding of various environmental pollutants, therapeutic chemicals or biological macromolecules, the resulting statistical models may be used for describing or predicting their corresponding NP-ligand interactions.

Statistical learning in the big data era

Statistical learning, as a data-based modelling approach, can reveal its true potential when applied to extremely large dataset. With the development of fast and high throughput analytical tools and accumulation of years of experimental studies, a comprehensive database for all nanoEHS related experimental data on most existing ENM categories can be established through worldwide collaboration, for the purpose of data analysis, organization, archiving and sharing. This strategy is especially promising for building predictive statistical models by incorporating informatics tools, and for predicting potential physicochemical interactions and biological effects for both medical and nanoEHS applications.

A large experimental database with multiple contributing sources requires careful curation to ensure the validity and completeness of the data.176 This requires detailed documentation of experimental conditions and reaction times during the experimental studies. For example, degree of dispersion of ENM in aqueous phase is usually critical for studies of physicochemical interactions, while dispersion is heavily influenced by the dispersion media, ionic strength and temperature. The comparison between data obtained at different conditions or models built excluding these factors would be considered invalid. ENM surface interactions, such as surface physisorption and biocorona formation, occur over time, while ENMs themselves – especially those of assembled nanostructures with complex internal compositions – could change over time due to agglomeration, dissolution and sedimentation. As a result, the time scales at which experiments are performed should also be included for the determination of equilibrium points and kinetics. In addition, when performing statistical learning on data collected from various sources, identification and exclusion of outliers due to batch-to-batch variations and false positive signals (from ENMs interacting with the chemicals in bioassays) may be extremely important for the generation of robust and reliable predictive models. With abundant data available in literature, another more feasible approach is to collect and analyse the existing data in nanoEHS. For example, Xu et al. developed a toolkit termed Nanomaterial Environmental Impact data Miner (NEIMiner), which includes a function for automatically scraping the web for relevant and heterogeneous ENM environmental data, subsequently establishing complex data structures for modelling.177 In addition, despite the limited amount of data available, a few working nanoEHS databases have been set up and running. For example, the NBI Knowledgebase (http://nbi.oregonstate.edu/) provides a comprehensive ENM library and a nano-bio interaction database categorised by nanomaterial properties such as core materials and surface functionalisations. Nanoinfo (nanoinfo.org) provides a central ENM safety database and modelling tools for assessing their environmental impacts. The Cancer Nanotechnology Laboratory portal (https://cananolab.nci.nih.gov/caNanoLab/) facilitates sharing of data on ENM characterisation and in vitro and in vivo assays.

Focusing on biocorona – a perspective from atomistic simulations

Proteins are usually the most abundant species within a biocorona. The biological identity of a NP is represented by convoluted properties of the NP and its bound proteins, rather than the NP itself on which majority of basic and toxicological research has focused upon to date.112, 178, 179 Such a NP-protein corona, whose formation and evolution primarily depend on the physicochemical properties of both NPs and proteins,140, 180–182 may initiate its contact with the cell to trigger cellular response. For instance, the proteins constituting the corona can interact with membrane receptors and initiate active cell uptake via endocytosis. The presence of protein corona can cause altered toxic response.54, 183 Formation of biocorona on the NP surface can also block functional ligands from interacting with targeted receptors, attenuating the designed functionality.184 On the other hand, interactions between NPs and proteins in the corona can also affect the structure, dynamics, and function of the protein constituents.185 The induced protein conformational changes might inactivate their native functions, and induce protein misfolding and aggregation.122 It has been shown that NPs can nucleate amyloid aggregation of proteins and possibly contribute to the development of protein misfolding diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s diseases, type 2 diabetes, and also the dialysis-related amyloidosis.122 The exposure of otherwise buried protein segments can also be targeted as foreign peptides to elicit an immune response.114, 186, 187 Hence, from the perspectives of health and safety it is important to uncover the structure and dynamics of the biocorona in order to establish correlations between the properties of pristine NPs and their biological and pathological functions.

Complementarity between computational modelling and experimental characterization

Previous research efforts have provided much insight into the various properties of NP-protein corona, such as the existence and size of the biocorona,8 protein composition and evolution on the NP surface,119, 120, 181, 188 impact of NP size and surface properties,53, 189–192 and the corresponding cellular responses.193–195 Protein binding with NPs is rather dynamic and the bound proteins can be partitioned into “hard” and “soft” coronae depending on binding affinities and exchange rates with solution. For example, despite thousands of protein types existing in the blood serum, only a few tens of proteins are found enriched in the hard corona,53, 119, 120, 189–192 a major determinant for the interactions between NPs and biological systems. However, molecular details of the NP-protein corona — such as the orientations of proteins bound to the NP, protein conformational changes upon NP-binding, protein-protein association and aggregation on the NP surface, and corresponding physicochemical determinants of these complex interactions — are largely unknown due to challenges in high-resolution experimental characterization, including NP-NP agglomeration, inherent heterogeneity of the system, and absence of solvent interactions in electron microscopy imaging. Accordingly, computational modelling can be used together with experimental studies to uncover the structural and dynamic details of complex molecular systems. By offering not only molecular insight to experimental observations but also experimentally testable hypotheses, computational modelling can bridge the gap between experimental phenomena and the underlying molecular systems of interest,196 thereby making significant contributions to our understanding of the structure, dynamics and function interrelationship of the biocorona and their biological and environmental implications.

Computational methodologies for studying the structure and dynamics of the nano-bio interface

A number of computational approaches that have been originally developed to study biomolecules in computational biophysics, such as quantum mechanics simulations (QM), molecular mechanics (MM/MD), molecular docking, dissipative particle dynamics (DPD), and their combinations,197, 198 have already been utilized to study the structural and dynamic properties of NP-protein corona at the molecular and atomic levels. Density function theory (DFT) based QM calculations can accurately describe the interaction energies of various configurationally states of a molecular system, but are computationally expensive. As a result, QM studies are often limited to interactions of small chemical groups with a NP surface or a small nano-cluster,198 which can be used to parameterize the classical mechanics interaction potentials between the NP and protein atoms for MD/MD simulations,199–201 or in conjunction with MD simulations of the binding proteins (i.e., the hybrid QM/MM simulations) to study NP-protein complexes.197

The MM/MD simulations have been thus far the most popular approach to study NP-protein corona.101, 198, 202–206 The traditional all-atom MD methods with explicit solvent model are capable of accurately describing molecular systems consisting of NPs and proteins in aqueous conditions, and have been successfully applied to describe the binding of proteins with fullerene,202, 203 carbon nanotube,101 and, more recently, metal NPs.198 Given the challenges of large system size and long timescales associated with biocorona formation and evolution, it is still difficult for all-atom MD simulations to reach the time and length scales required for depicting large NP-protein systems till equilibration.207, 208 Coarse-grained (CG) MD simulations,209 where certain groups of atoms are simplified as single pseudo “atoms” and effective interactions are assigned between these atoms, can be used to study large systems and reach long time scales.210, 211 Enhanced sampling methods such as GPUs212 have also been explored for CG MD simulations to study the corona formation between NPs and multiple proteins. While CG simulations have been applied to study the general aspects of NP-protein interactions,204, 209, 212–216 they often have limited predictive power and lack sufficient molecular details for modelling specific molecular systems. Multiscale approaches,217 where long time-scale simulations with CG models and short time-scale simulations with the all-atom model are coherently blended together,218, 219 have been applied to study the effect of NP surface pattern on protein binding204 and characterize the structure and dynamics of biocorona formation with AgNPs.100, 205

Discrete molecular dynamics (DMD) is a special type of MD approach that has also been applied to study the nano-bio interface.126, 136, 205, 206, 220–222 DMD methods use discontinuous instead of continuous potential functions to describe inter-atomic interactions,223, 224 which improves the computational efficiency by avoiding frequent calculations of acceleration and position updates in the traditional MD approach. Both all-atom136, 221, 225 and CG217, 222 DMD methods have developed to model the nano-bio interface. With the high computational efficiency of DMD and application of multiscale modelling approach, Ding et al. reported the formation of single- and multi-layer protein corona on an AgNP surface205 and uncovered a stretched-exponential protein binding kinetics observed experimentally.226 Qing and Carol applied CG DMD simulations to study the isotherm properties of protein absorption to a NP using a large number of CG proteins.222 DMD simulations have also been recently applied to study the effect of NPs on protein amyloid aggregation.126, 221, 227

Other methods like molecular docking and DPD have also been applied to study the possible binding between NPs and proteins. Since docking simulations usually assume a rigid protein receptor, the method cannot be used to study the conformation changes of proteins often observed upon NP binding. DPD methods usually use CG representation of the molecular system and are often used to model the mesoscopic phenomena instead of the structure and dynamics of NP-protein corona at the atomic level. For instance, applications of DPD in the uptake of NPs with biomembranes have been recently reviewed.228

Applications of computational modelling in conjunction with biophysical and biochemical characterization have already provided much insight at the atomic and molecular level, such as binding poses of proteins in the corona,100, 198, 205 conformational changes of proteins upon binding with NPs and nanostructures,101, 202, 207, 229 and effects of NP size, shape,230 and surface chemistry206 on protein binding. Due to computational limitations, most of the computational studies in literature aimed to uncover high-resolution structural and dynamic information have been focused on simulations of single proteins interacting with a single NP, which is usually not the case in vitro and in vivo. Recently, computational modelling efforts have been devoted to understand the effects of NPs on complex biological processes involving multiple biomolecules, such as protein-protein recognition231, 232 and protein aggregation.215, 227, 233, 234 In the following section, we will focus on recent computational and modelling studies concerning the effects of NPs on protein aggregation, where efficient modelling of multiple proteins in the presence of NPs in silico becomes necessary. Understanding the physicochemical determinants of NPs on protein aggregation may help design “safe” non-amyloidogenic NPs or nanomedicine with anti-amyloid properties, thereby contributing to the central goal of nanoEHS.

Complex effects of NPs on protein amyloid aggregation

Protein misfolding and amyloid aggregation are associated with a wide range of human diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s diseases, and type-2 diabetes.235–238 Despite their differences in sequence and structure, amyloidogenic proteins associated with these diverse diseases assume the same characteristic cross-β structure in their final fibrils, where misfolded proteins form extended β-sheets along the fibril axes.239–244 Many recent studies suggest that intermediate oligomers populated along the aggregation pathway, rather than the final amyloid fibrils, are the toxic species.245–247 Motivated by the possibility of NPs crossing the blood-brain-barrier,248–251 much effort has been devoted to understanding the effect of NPs on protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases, such as that of amyloid-beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease,122, 123, 215, 233, 252–257 islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) in type 2 diabetes,126, 221 and beta-2 microglobulin in dialysis-associated amyloidosis.122 Given advancements in nanotechnology and nanomedicine, many studies have also been focused on understanding the impact of ENMs on protein aggregation. For instance, drug delivery using NPs with inhibitory effects on amyloid aggregation may have additional therapeutic effects in treating protein misfolding diseases.

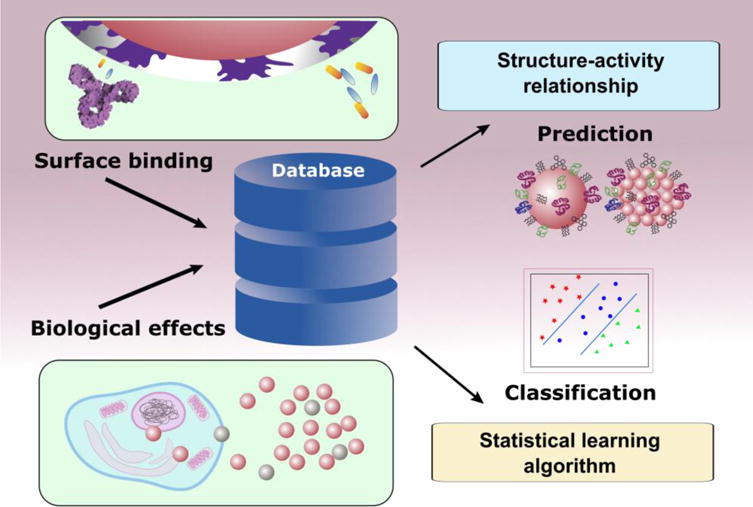

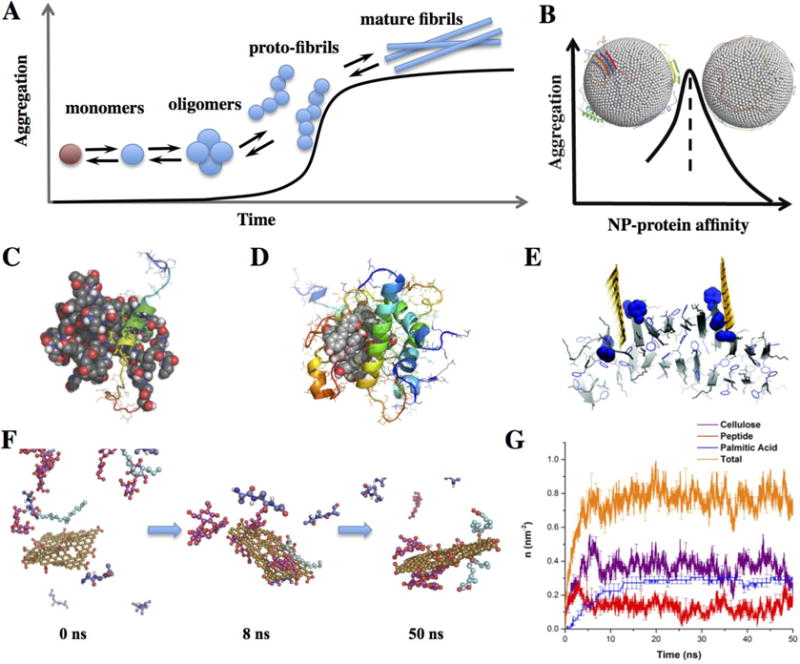

Protein aggregation is a highly complex biological process depending on many physicochemical properties of both the aggregating proteins (natively folded or intrinsically disordered, thermos-stability, and concentration) and their environments (pH, temperature and ionic strength). Usually, amyloid aggregation can be described by a nucleation process characterized by a lag time followed by a sigmoid increase of amyloid fibrils (Fig. 4A).258 The nucleation step is initialled by the formation of critical oligomers of the amyloidogenic protein or peptide monomers (a natively folded protein usually undergoes partial unfolding into an aggregation-prone state259). With the addition of more monomers, the oligomers elongate into proto-fibrils, corresponding to a rapid increase of aggregates. Mature fibrils are formed by bundling of multiple proto-fibrils. Since the introduction of NPs can interfere each of these steps depending on the NP’s affinity for various molecular species along the aggregation pathway, both aggregation promotion and inhibition have been reported.122, 233, 234, 252, 255–258 Using CG DMD simulations, it was demonstrated that differences in NP-protein binding affinity and their relative concentration contributed to the complex NP effect on amyloid aggregation (Fig. 4B).227 Atomistic MD simulations have also been applied to explore the inhibition of amyloid aggregation by targeting various molecular species along the aggregation pathway (Fig. 4A), including the monomers (Fig. 4C),126 oligomers (Fig. 4D),260 and also the amyloid fibrils (Fig. 4E).234

Figure 4. Effects of NPs on protein aggregation.

(A) Sigmoidal amyloid aggregation kinetics. A natively folded protein (brown sphere) undergoes partial unfolding or misfolding to the amyloidogenic state (cyan sphere). The nucleation process corresponds to the formation of critical oligomers (the species with the highest free energy barrier). A NP interferes with the aggregation process by interacting differentially with the molecular species along the aggregation pathway. (B) Dependence of amyloid aggregation on NP-protein interaction strength. The left inset depicts aggregation of peptides on a NP surface, while the right one shows proteins fully interacting with the NP rather than with other proteins.227 (C) Stabilization of IAPP monomer in a helical conformation by encapsulation and binding with PAMAM dendrimer.126 (D) Formation of “off-pathway” oligomers by polyphenol nano-clusters.260 (E) Disruption of amyloid fibrils by graphene.234 (F) Competitive binding of natural amphiphiles – i.e., cellulose (red), peptide (blue), palmitic acid (cyan) - with a graphene oxide nanosheet (yellow).220 (G) The number density of molecules, n, bound to the nanosheet as a function of time.220

Atomistic DMD simulations have recently been applied to elucidate the competitive binding of natural amphiphiles including celluloses, peptides, and lipids with graphene oxide nanosheets (GRO),220 where lipids and peptides displayed stronger binding to GRO than celluloses. Given differential population of natural amphiphiles in the environments (e.g., cellulose is most populated in algal exudates, followed by peptides and lipids), a Vroman-like competitive binding phenomenon was observed, where the most abundant celluloses bound to GRO first but were later replaced by stronger binding lipids with less abundance (Fig. 4F,G).

Despite the capacity of computer simulations in revealing the inner workings of the biocorona that is often beyond the resolution of statistical modelling, including the composition, crowding and aggregation of the biocorona in response to time, temperature, pH, salt strength, heterogeneity and concentration of natural amphiphiles, pollutants and exudates, current research in nanoEHS lacks such a viable computational element. As the structure, dynamics and function of the biocorona entail rich toxicological and pathological implications, the value of computer simulations will likely be increasingly acknowledged and utilized for advancing nanoEHS research in the new era.

Outlook

To ensure its sustainability, research in nanoEHS should be purposefully aligned with ENM synthesis and move beyond simple materials to sophisticated and smart ENMs used in real-world applications.261, 262 For example, there has been a vast pool of polymeric and polymeric-condensed hybrid nanocarriers and nanoconstructs developed for gene and drug delivery.110 Such nanostructures are often grafted with polyethylene glycol (PEG), poly(alkyl cyanoacrylate) or poly(lactic acid) to avoid protein fouling and prolong their blood circulation. However, PEG is not biodegradable and has been found prone to the adsorption of apolipoproteins A-1 and E as well as complement proteins that play important roles in immunogenicity.263–266 Furthermore, these nanostructures have rarely been examined beyond their in vitro and in vivo toxicities determined by fluorescence and histology assays. Indeed, the efficacy of drug delivery has not improved over the past two decades despite global investment and active research,267 partly because of a lack of understanding of nano-biomolecular interactions and their implications on the whole organism level. In this regard, collaboration between nanomedicine and nanoEHS could prove cost effective and mutually beneficial.

Antibacterial applications of ENMs is another area which could benefit from improved understanding of nano-bio interactions.95, 268–275 Current ENM-based antibacterial applications usually rely on mechanisms acting through toxic ions, ROS, oxidative stress and membrane damage elicited by NPs (e.g. Ag, CuO and ZnO NPs, carbon nanotubes and graphene derivatives) bound to bacterial cell wall or taken up by bacterial cells.21, 22 Further development in this arena could exploit interactions of novel ENMs with bacterial EPS as well as inhibition of functional amyloids associated with bacterial genera such as certain E. coli and Pseudomonas strains.276–279 In addition, with highly active research in green chemistry and biosynthesis of antibacterial ENMs using extracts and extracellular substances from various organisms,280, 281 it is increasingly important to focus on the biocorona formed during NP synthesis to avoid introducing potentially cytotoxic biomolecules. This area is potentially rewarding scientifically, with far-reaching implications in medicine, food science, agriculture, wastewater treatment, and environmental remediation and engineering.

With the rapid improvement of computational power there is an increasing potential of using computer simulations and statistical modelling for research in nanoEHS. Both approaches can take into consideration of long-range electrostatics (pH, water hardness, and charges of NPs and natural amphiphiles), short-range van der Waals forces, hydrophobic interaction, hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking, as well as the aspects of protein/lipid concentration, crowding, and temperature that varies from season to season and region to region.282 Recent development of molecular modelling of the nano-bio interface has significantly expanded the boundary of single NP-protein complexes to larger, more sophisticated, and more realistic systems. As large experimental data are being generated at an increasing rate, especially with the incorporation of industrial automation into research laboratories, advanced statistical learning algorithms are needed to extract valuable information to understanding the nature of the interactions and make further assessments and predictions. In addition, applications of methodologies adopted from proteomics and lipidomics in nanoEHS often generate large volume of mass spectral data, which can be viewed as the biomacromolecular fingerprints of respective ENMs. Towards that end, advanced informatics algorithms with big data capabilities are essential for the advancement of nanoEHS.

We envisage that a broad range of nanotechnology-based environmental applications would benefit from the integration of the tools discussed above. The development of simulation methodologies will allow systematic design and manufacturing of nano-enabled products from basic nano-bio interaction principles, e.g. membranes for water and air filtration could be designed specifically based on the affinity between the membrane materials and intended pollutants. The established QSAR profiles of ENMs could be used as guidelines for the design of catalytic treatment based on redox-active NPs or nanostructures. We believe that high-throughput and predictive toxicological methods can significantly contribute to elucidating adverse outcome pathways of ENMs that are gaining increasing scrutiny283 and are proposed to be incorporated into risk assessment of ENMs.284 Recently, surface affinity and dissolution rate were identified as critical functional assays for characterizing ENM behavior.285 We anticipate that biocorona characterization with experimental methods, modelling and simulations would greatly advance nanoEHS research and assist ENM risk assessment. Taking advantage of predictive toxicological approaches and high throughput screening platforms, we anticipate integration of safety assessment into mainstream nanotechnology research to support safe manufacturing. Knowledge generated through such endeavours will not only serve the first generation of ENMs, but also the new generation of advanced nanostructures and nanosystems.

With the fusion of expertise from structural biology, biophysics, proteomics, analytical and polymer chemistry, computational science and technology, pharmaceutical sciences and nanomedicine, nanoEHS is poised for its transition from a nascent field centred on nanotoxicology to a more mature, multidisciplinary and broadly defined area of research centred on real-world applications and relevance in the coming decade. Towards that end, understanding biocorona may prove pivotal for the design of smart ENMs with minimal ecological footprint.

Environmental Significance.

The current literature concerning environmental health and safety of nanomaterials (nanoEHS) is often focused on describing the phenomenological consequences of nanomaterial exposure and the toxicity of nanoparticles to cells and model organisms. A wealth of information on nano-biomolecular interactions has not been fully exploited making it difficult to identify nano-specific effects as well as trace the origin of toxicity. We believe continued development of nanoEHS hinges on a critical extension from reporting macroscopic and microscopic phenomena to understanding nano-biomolecular interactions. This new frontier will facilitate resolving the interplay between nanomaterials and natural systems that elicits beneficial or detrimental effects on human and environmental health.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Recruitment Program of “Global Young Experts” and Startup Funds from Tongji University (Lin), NSF CAREER grant CBET-1553945 (Ding), NIH MIRA 1R35GM119691 (Ding), MIPS Internal Grant (Ke), ARC Project No. CE140100036 (Davis), and The Kansas Bioscience Authority (Riviere). The authors thank Pengyu Chen, Priyanka Bhattacharya, Alexander Gogos, Vera Slaveykova and Bo Wang for contributions highlighted in this review. R.C. thanks Mal Rooks Hoover, CMI for help with illustration.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no conflicting financial interests.

References