Abstract

In this study, we aimed to characterize fungal samples from necrotic lesions on collar regions observed in different sweetpotato growing regions during 2015 and 2016 in Korea. Sclerotia appeared on the root zone soil surface, and white dense mycelia were observed. At the later stages of infection, mother roots quickly rotted, and large areas of the plants were destroyed. The disease occurrence was monitored at 45 and 84 farms, and 11.8% and 6.8% of the land areas were found to be infected in 2015 and 2016, respectively. Fungi were isolated from disease samples, and 36 strains were preserved. Based on the cultural and morphological characteristics of colonies, the isolates resembled the reference strain of Sclerotium rolfsii. Representative strains were identified as S. rolfsii (teleomorph: Athelia rolfsii) based on phylogenetic analysis of the internal transcribed spacer and large subunit genes along with morphological observations. To test the pathogenicity, sweetpotato storage roots were inoculated with different S. rolfsii strains. ‘Yulmi’ variety displayed the highest disease incidence, whereas ‘Pungwonmi’ resulted in the least. These findings suggested that morphological characteristics and molecular phylogenetic analysis were useful for identification of S. rolfsii.

Keywords: Fungal morphology, Ipomoea batatas, Molecular phylogeny, Pathogenicity, Sclerotium rolfsii

Sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas) is a common plant of the Convovulaceae family and is ranked as the seventh most important food crop in terms of production; in developing countries, sweetpotatoes rank fifth in economic value production, sixth in dry matter production, seventh in energy production, and ninth in protein production and have many applications as foods, feeds, and industrial products [1,2]. Roughly 80% of the world's sweetpotatoes are grown in Asia. In addition to China and Vietnam, sweetpotatoes play important roles in the rural economy in many other parts of Asia, including the Philippines, India, Korea, Taiwan, some eastern islands of Indonesia (Bali and Irian Jaya) and Papua New Guinea [3,4]. In Korea, the sweetpotato is widely cultivated and consumed, and the total area of cultivation reached as much as 22,000 ha of land in 2015, which was 27% higher than that in 2000 [5].

Numerous fungal diseases have been reported on sweetpotatoes from different regions worldwide. Sclerotial blight is a major fungal disease caused by Sclerotium rolfsii during the early cultivation period and has been observed in plant beds, mature plants as circular spots, and tubers as a post-harvest disease. S. rolfsii Sacc. (teleomorph Athelia rolfsii [Curzi] C. C. Tu. & Kimbr.) is a serious disease-causing fungal pathogen that affects diverse crops grown around the world, particularly tropical and subtropical countries [6]. Because of its broad host range, S. rolfsii is considered one of the most destructive pathogens worldwide; indeed, about 500 plant species from 100 families, including tomatoes, potatoes, chili peppers, carrots, cabbage, sweetpotatoes, common beans, and ground nuts [7,8], are affected by this pathogen. The fungus generally infects the collar region or stems near the soil surface and spreads over the whole plant or fruits and remains in soil surface [9,10]. S. rolfsii produces sclerotia on hosts, survives and overwinters for a long time and infects the same host crop or other nearby crops [7,11].

Various molecular approaches have been employed to identify S. rolfsii and other fungal populations [12,13,14,15]. The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) is common genomic target used to measure fungal diversity at the molecular level [6]. The level of divergence between species or strains or within the species examining by ITS rDNA sequences is low; however, this method shows improved sensitivity at the genus level [16]. The ITS and large subunit (LSU) show slight phylogenic differences among species that are closely related to S. rolfsii (e.g., S. coffeicola and S. delphinii) [17]. However, no studies have performed molecular analysis along with morphological characterization of S. rolfsii in sweetpotatoes in Korea. Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to evaluate disease occurrence on sweetpotatoes by S. rolfsii, analyze the molecular data by ITS and LSU sequences and morphological characteristics of the pathogen, and test their pathogenicity on different variety.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Disease symptom and incidence

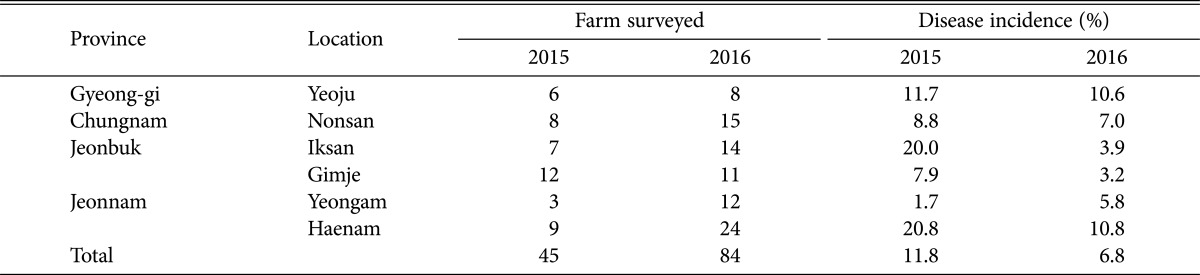

Initially sudden wilting of the stalks appeared in plant beds followed by deaths (Fig. 1A). In high humid conditions the disease spreads and infection was initiated near the collar regions and soon after infections, necrotic lesions were observed along with aerial cottony, coarse, white mycelia (Fig. 1B and 1C). Mycelium covers the soil surface and produced mycelial mats. After that sclerotia appeared large in numbers on the mycelial mats, mats and sclerotia were found on the surface layer of the newly grown storage roots. Then, disease incidence was measured as the proportion of a plant community that is diseased. Field surveys were conducted in farmers' fields in 6 different locations of Yeoju, Nonsan, Iksan, Gimje, Yeongam, and Haenam (Table 1). During the survey of disease incidence, we inspected 45 and 84 farmlands in 2015 and 2016, respectively, and monitored the presence of disease and the affect land area. After obtaining data from different locations, we calculated the disease incidence by the following formula [18].

Where, ‘I’ is the disease incidence, ‘ni’ is the total number of affected plants, and ‘N’ is the total number of evaluated plants.

Fig. 1. Symptoms of sclerotial blight disease observed in different farmers' field in Korea during 2015 and 2016. Sudden wilting and deaths of seedlings (A), appearance of mycelia on the collar region of seedlings (B), aerial mycelia, mycelial mat along with sclerotia observed on rootzone soil (C, D).

Table 1. Sclerotial blight disease incidence of sweetpotato in different locations in Korea during 2015 and 2016.

Pathogen isolation and culture maintenance

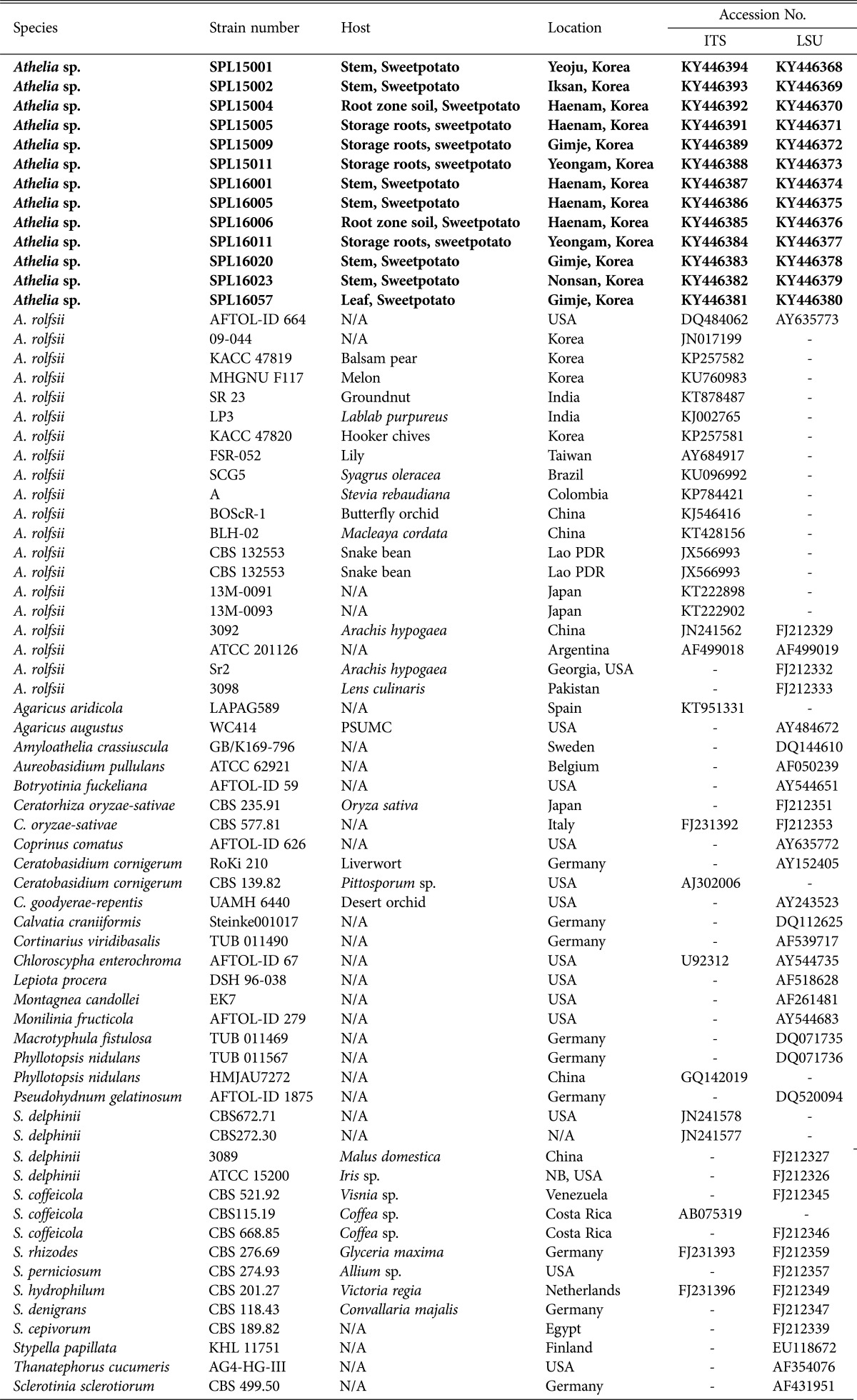

Leaves, roots, stems, and storage roots affected by Sclerotium blight disease were collected and were transported to the laboratory. Samples were washed under running tap water and dried in a laminar air flow chamber. After surface sterilization [19], samples were cut into small pieces, dried, and transferred to potato dextrose agar (PDA) supplemented with rifampicin to stop bacterial growth. PDA petri dishes were then incubated at 25℃ for 3–7 days. Plates were checked on a regular basis by the naked eye for hyphal growth. Hyphae were then transferred to PDA, and pure cultures of Sclerotium-like fungi were prepared. A total of 36 strains were obtained after confirming pure cultures by growing on PDA several times. Fungi were then assigned identification numbers (Table 2), maintained in PDA slant tubes and 20% glycerol stock solution, and deposited in the culture collection of the Sweetpotato Laboratory, Bioenergy Crop Research Institute, Rural Development Administration (RDA), Muan, Korea.

Table 2. Isolates collected from different sweetpotato growing regions in Korea during 2015 and 2016.

Bold letters indicate the experiment conducted in the present study and assigned accession numbers.

ITS, internal transcribed spacer; LSU, large subunit; SPL, Sweet Potato Lab., Muan, Korea; N/A, not applicable; -, not found; AFTOL, Assembling the Fungal Tree of Life, Germany; KACC, Korean Agricultural Culture Collection; CBS, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, USA; TUB, Herbarium Tubingense, Germany.

Morphological characterization

Fungal strains were grown on PDA and malt extract agar (MEA) at 25℃ in the dark to examine morphological characteristics. Small discs (0.5mm diameter) were cut from the margins of developing colonies, transferred to the center of PDA and MEA plates, and incubated at 25℃. We observed the colony growth rate (speed/day), the production of clamp connections on mycelia, and evaluated aerial mycelium, sclerotia formation and sclerotial size, shape, and color for each of the strains using a AX10 microscope (Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany) with an Artcam 300 MI digital camera (Artray, Tokyo, Japan). Colors were named using the Mycological Colour Chart [20]. Morphological characteristics of the isolates were then compared with previous descriptions.

DNA extraction, PCR, and sequencing

All the selected fungal isolates were grown on PDA for 7 days. Mycelial tuffs of each colony were transferred to 1.8mL eppendorf tubes. Genomic DNA was extracted with Solgent Genomic DNA Prep Kit (Solgent Co. Ltd., Daejeon, Korea) following the manufacturer's instructions. A portion of the ITS and LSU regions of rDNA was used for PCR amplifications with the following primer pairs ITS5 (5′-GGA AGT AAA AGT CGT AAC AAG G-3′)/ITS4 (5′-TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC-3′) [21] and LROR (5′-ACC CGC TGA ACT TAA GC-3′)/LR5 (5′-TCC TGA GGG AAA CTT CG-3′); and the products generated by PCR was used for sequencing [22]. PCR amplification was carried out using a BIO-RAD PCR System T100 thermo cycler (BIO-RAD Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) with a 50 µL reaction volume containing 5 µL 10 × e–Taq reaction buffer (Solgent Co. Ltd.), 1 µL 10 mM dNTP mix, 1 µL each primer, 1 µL template DNA solution, 1.5 µL U Taq-DNA polymerase and sterilized distilled water. PCR was carried out under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94℃ for 95 sec, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94℃ for 35 sec, annealing at 49℃ for LSU and 55℃ for ITS for 60 sec, and the final extension at 72℃ for 2 min. PCR products were then purified using a Wizard PCR Preparation Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and sequenced by a commercial sequencing service provider (Macrogen, Daejeon, Korea). The resulting sequences were deposited in GenBank and assigned accession numbers (Table 2).

Phylogenetic analysis

All nucleotide sequences generated in the present study and retrieved from the GenBank (Table 2) were assembled using PHYDIT program ver. 3.2 [23] and initially aligned with the Clustal X v.1.83 program [24]. The sequences were then imported into BioEdit v.5.0.9.1 program for manual adjustment [25], if necessary. Phylogenetic relationships were estimated by a maximum parsimony (MP) analysis using MEGA 6 program [26]. Bootstrap analysis using 1,000 replications was performed to assess the relative stability of the branches.

Pathogenicity test

Six selected isolates of Sclerotium (SPL15001, SPL15004, SPL15011, SPL16001, SPL16023, and SPL16057) were tested on six different varieties of sweet potato storage roots with three replications. Varieties inoculated with pathogens were Juhwangmi, Dahomi, Yulmi, Pungwonmi, Sinjami, and Jinhongmi. Three storage roots from each variety were washed in running tap water and sterilized as previously described methods [27] with minor modifications. Samples were then washed three times with distilled water to remove surface sterilizing agents. Hyphal disks of each colony (5 mm), previously grown on PDA, were placed on storage roots by generating a wound with a 5-mm cork borer. Four wounds were made in a single storage roots; one was used as a control, and the others were inoculated with Sclerotium isolates. Tubers were then transferred to a sterilized plastic mesh platform in moistened clean boxes. To develop disease, the boxes were incubated up to 10 days at 25℃ in the dark. After incubation, the diameters of necrotic lesions were measured and scored using a 5-point rating system, where 0 = no symptoms, 1 = diameter less than 5 mm, 2 = diameter of 5–10 mm, 3 = diameter of 10–15 mm, 5 = diameter greater than 15 mm. All controls were treated with nonfungal blank PDA disks. To fulfill Koch's postulates, fungi were re-isolated from artificially inoculated tubers to confirm the presence of Sclerotium species. The re-isolated fungi were cultured on PDA, colony characteristics were observed, and sclerotia formation was monitored and compared with that of the original isolates.

RESULTS

Disease symptom and incidence

During our survey, blight disease was observed on the basal parts of crops during their early stages of growth. Small and necrotic lesions were observed at early stage and later stages of growth, and symptoms were enlarged and spread over the plants and fields (Fig. 1). White, dense, fluffy, aerial, cotton-like mycelium remained in the soil surface in heavily affected fields. During 2015 and 2016, 45 and 84 farmlands were visited, respectively, to monitor sclerotial disease. The results revealed that the disease rates were 11.8% and 6.8%, respectively. Yeoju and Haenam farmers experienced higher disease rates of 10.8% and 10.6%, respectively, in 2016 (Table 1), whereas Gimje and Iksan farmlands showed lower disease rates of 3.2% and 3.9%, respectively. The average disease rate in 2015 (11.8%) was higher than that in 2016 (6.8%). The highest disease incidence was recorded in Haenam in 2015 (20.8%).

Morphological characterization

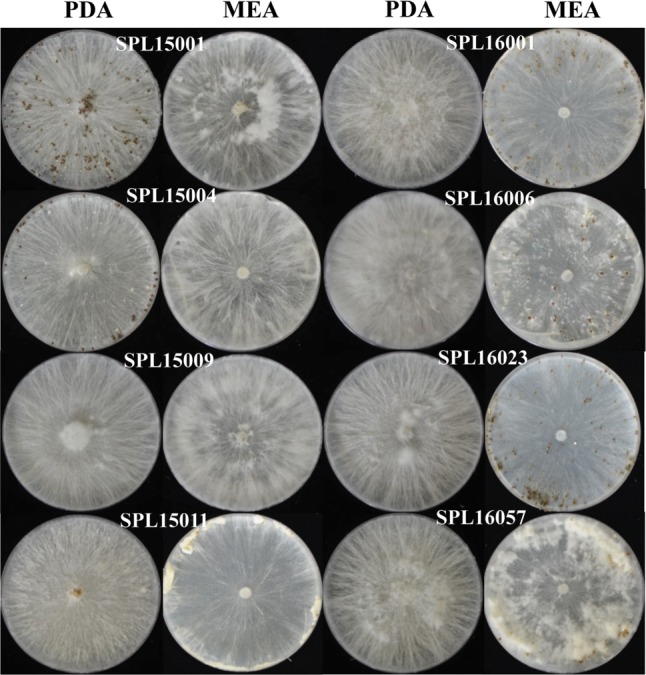

Colonies of all isolates were white to pale olive buff in color (Fig. 2). The growth rates of the colonies were recorded for 5 days and the average colony growth rate was 1.2–1.5 mm/day. The isolate SPL15001 showed the highest colony growth rate (1.5 mm/day) among all isolates. After 10 days of incubation, spherical sclerotia started to grow and all the isolates produced clamp connections. During the early stage of sclerotial growth, the color was white to pale light brown; however, the color changed to cinnamon brown or dresden brown over time.

Fig. 2. Colony morphology and sclerotia production of selected fungi on potato dextrose agar (PDA) and malt extract agar (MEA). Compact morphology—SPL15004, SPL15009 on PDA and SPL16001, SPL16023 on MEA.

Sclerotial size varied from 0.5 to 2.0 µm (Table 3). Some isolates showed larger (max. 2.0 µm) sclerotia, and some produced smaller sclerotia (0.50–1.0 µm). The sizes of sclerotia in isolates SPL15004, SPL16023, and SPL16057 (0.5–2.0 µm) were larger than those of the other five isolates examined in this study.

Table 3. Morphological characteristics of eight representative isolates of Sclerotium rolfsii obtained from different locations in Korea.

Molecular characterization

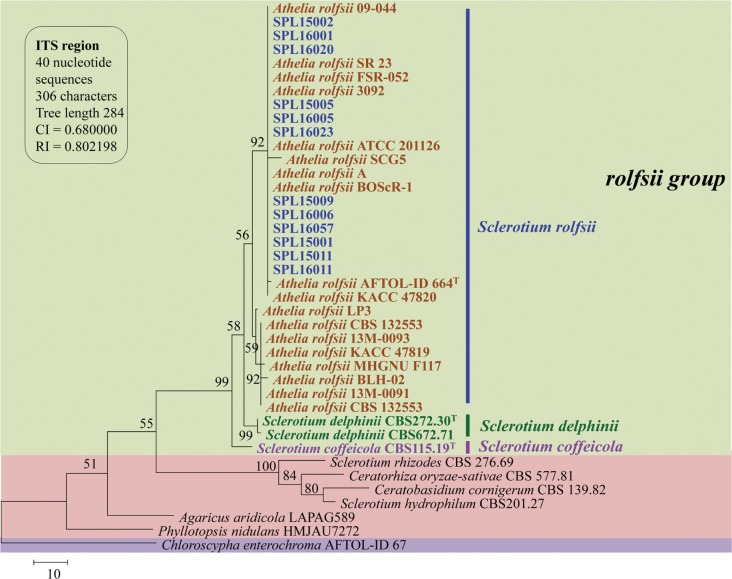

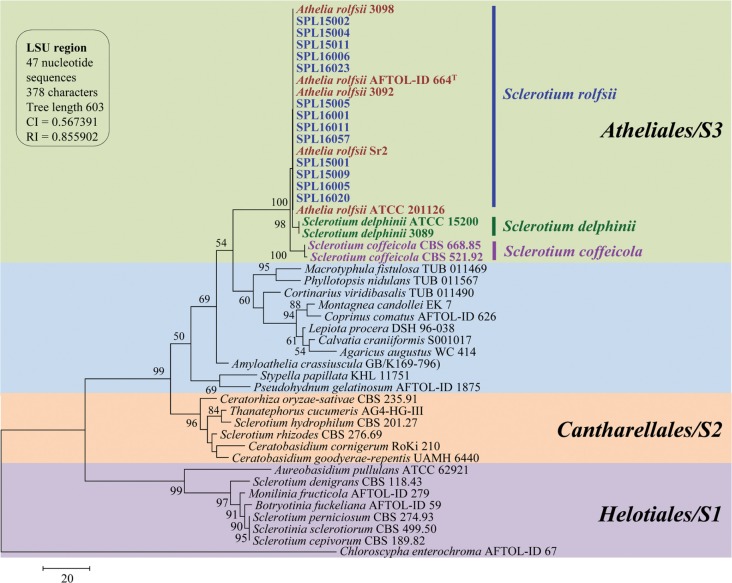

A total of 13 isolates were sequenced, and all sequences of ITS and LSU gene showed 99–100% similarity with Athelia rolfsii (anamorph: S. rolfsii) sequences from GenBank by BLAST search analysis. Parsimony analysis of ITS sequences showed three species of Sclerotium (S. rolfsii, S. delphinii, and S. coffeicola) produced a single group with a high (99%) bootstrap value. For construction of a phylogenetic tree, we used sequences of S. rolfsii collected worldwide, along with S. delphinii and S. coffeicola. S. delphinii and S. coffeicola produced a separate subgroup, supporting that the isolates identified in this study were different from these two species (Fig. 3). MP analysis of the LSU sequences resulted in two equally most parsimonious trees. A tree was selected to illustrate the phylogenetic location of the present isolates. Parsimony analysis (MP) of all sequences produced three major clusters, designated as S1, S2, and S3. S. denigrans, S. cepivorum, S. sclerotiorum, and S. perniciosum were included in the S1 cluster together with Monilinia fructicola and Botryotinia fuckeliana, which was under sclerotiniaceae (Helotiales, Ascomycota). S. hydrophilum, S. rhizodes, Thanatephorus cucumeris, and Ceratorhiza oryzae-sativae clustered together as the S2 group within Cantharellales (Basidiomycota). S. rolfsii, S. delphinii, and S. coffeicola clustered together with a maximum bootstrap value (100%) in the S3 group (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. Parsimonious tree of partial sequences of the internal spacer region (ITS) of rDNA from Athelia species and other Basidiomycota and Ascomycota showing the relationships of present isolates and reference species. The tree is rooted with Chloroscypha enterochroma. Tree length = 284, consistency index = 0.680000, retention index = 0.802189, and composite index = 0.598824 for all sites. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) is shown next to the branches. Bootstrap values > 50% are indicated above branches. The analysis involved 40 nucleotide sequences. Present isolates are shown in bold with blue color and ‘T’ indicates type srtain.

Fig. 4. One parsimonious tree of partial sequences of the 28S large subunit region (LSU) of rDNA from Athelia species and other Basidiomycota and Ascomycota. The tree is rooted with Chloroscypha enterochroma. Tree length = 603, consistency index = 0.563791, retention index = 0.855902, and composite index = 0.573440 for all sites. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) is shown next to the branches. Bootstrap values > 50% are indicated above branches. The analysis involved 47 nucleotide sequences. Present isolates are shown in bold with blue color and ‘T’ indicates type srtain.

Pathogenicity test

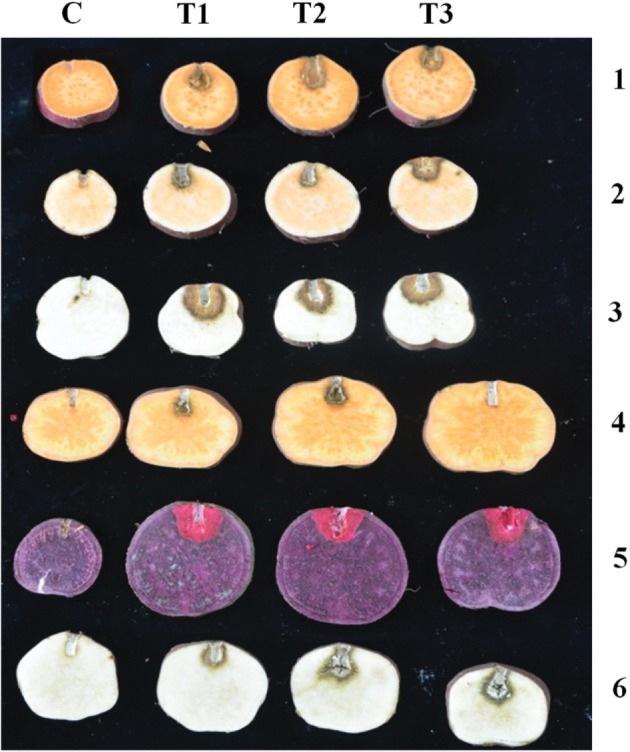

For different varieties of storage roots, lesions of S. rolfsii occurred after inoculation with mycelial disks. The six different isolates exhibited similar pathogenicities on the tested storage roots; however, the pathogenicity range varied among isolates. Isolate SPL16001 produced higher disease severity than isolate SPL16004. In every case, the ‘Yulmi’ variety showed higher susceptibility to S. rolfsii, whereas ‘Pungwonmi’ showed better resistance to S. rolfsii (T1, T2, and T3 in Fig. 5). No symptoms were observed on control storage roots C in Fig. 5. Pathogens from infected storage roots were re-isolated, and their identity was confirmed.

Fig. 5. Pathogenicity of Athelia rolfsii SPL16001 on different varieties of sweetpotato storage roots. C, control line; T (T1, T2, and T3), treatment line with the SPL16001 isolate and numerical 1–6 represent the Korean local varieties of Juhwangmi, Dahomi, Yulmi, Pungwonmi, Sinjami, and Jinhongmi, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Sclerotial blight on Ipomoea batatas caused by S. rolfsii is a common plant disease found worldwide. In sweetpotatoes, disease develops during the seedling stage after transplanting into contaminated soil. When environmental conditions are humid, cotton-like mycelia develop around the basal part of the plants and spread through the soil. Disease incidence becomes severe at later stages of growth. The pathogen also attacks sweetpotato storage roots during storage, leading to circular spot disease [1], which appears in fields before harvesting. Lesions are circular and whitish or yellowish brown in color. Kim et al. [28] surveyed stem rot in sweetpotatos caused by S. rolfsii from 2007 to 2009 but the survey was limited to one location, which revealed that 23.1%, 26.7%, and 34.5% of seedlings were affected by the pathogen in 2007, 2008, and 2009, respectively. In the present study, we surveyed six sweetpotato growing regions and found that the disease rates were 11.8% and 6.8% in 2015 and 2016, respectively. The disease incidence was decreased because of the use of resistant and disease-free sweetpotato varieties by the farmers. Notably, variations in disease incidence caused by S. rolfsii have been observed worldwide. For example, in stem rot of tomatoes in Korea, the disease rate was 8.2% [29]; in contrast, disease rates have been reported to be as high as 22% in pumpkin fields in India [10], 30% in candy leaf plants in Italy [30], 10% in Chinese Macleaya cordata [31], and 30–35% in common beans in India [32]. Moreover, wild coffee plants in India have been reported to have a high disease incidence of 47.36% [33].

Morphological studies are essential for characterizing S. rolfsii isolates from different geographical locations. In the present study, morphological variability was observed among S. rolfsii isolates, with variations in mycelial growth rates, colony morphology, production and arrangement of sclerotia, and number, size, and color of sclerotia. Both silky-white mycelia and fluffy or compact colony type were observed when isolates were cultured on PDA and MEA. Of eight isolates, SPL15009, SPL16001, SPL16006, SPL16023, and SPL16057 were fluffy on PDA, and others (SPL15001, SPL15004, and SPL15011) were compact; in contrast, SPL16001 and SPL16023 were compact on MEA, and the others showed fluffy colony morphologies, consistent with other studies [11,34,35].

Sclerotia formation was observed after 10–16 days of incubation at 25℃. Spherical (rarely spherical to irregular) sclerotia were whitish at the beginning and turned cinnamon brown or cinnamon to dresden brown over time. Additionally, variations in sclerotia production were observed, consistent with a previous report by Akram et al. [34]. Indeed, scleroia production can vary among isolates, and same isolate can produce different numbers of sclerotia on different dishes, even if the environment is constant [34,35]. Sclerotial arrangements or distribution patterns were mostly central, spread over the whole petri dish; few isolates showed peripheral arrangements, distinguishing these isolates from S. coffeicola and S. delphinii [36], which show ring-like sclerotial distributions or peripheral and ring-like structures, respectively.

Sclerotial size is an important characteristic feature for separating S. rolfsii from the other two neighboring species. In the present study, the size of the sclerotia varied with isolates. Average sizes of the isolates were 0.5–2.0. Similar sizes have been reported from S. rolfsii in different crops in Korea. For samples, sclerotial sizes from S. rolfsii were 1.0–3.0, 1.0–2.7, 1.0–3.0, and 1.0–3.0 mm in Convallaria keiskei [37], corn [38], Capsicum annuum [39], and Allium sativum [40], respectively. Mahadevakumar and Janardhana [33] characterized the morphology of S. rolfsii and showed that sclerotia size varied from 0.5 to 2.5 mm, similar to the present study results. The fluffy nature of sclerotia on PDA, their small sizes, and their colors distinguished this fungal species from S. delphinii and S. coffeicola (3.0–5.0 mm; S. delphinii Ochraceous: tawny to buckthorn brown, S. coffeicola: yellow ocher to buckthorn brown) [41]. The morphological observations of the isolates completely matched with the description of S. rolfsii [42]; therefore, the fungal strains in this study were identified as S. rolfsii Sacc. (teleomorph: Athelia rolfsii (Curzi) Tu and Kimbrough).

Parsimony analysis of all ITS sequences of the isolates from the present study revealed that the references sequences of A. rolfsii, A. coffeicola, and A. delphinii clustered together in a group and suggested that these three species were closely related to each other. S. delphinii and S. coffeicola produced a separate subgroup in the same cluster, which separated these two species from S. rolfsii. Similar ITS phylogeny described earlier on S. rolfsii and explained the same as of the present study [10,14,16,32,33,34,35]. They showed the similarity among the above mentioned three species of Sclerotium species and narrated slight differences of S. rolfsii with the others [43,44,45]. Harlton et al. [36] described that S. rolfsii and S. delphinii clustered together and S. coffeicola separated by different closely related cluster, whereas Adandonon et al. [43] mentioned that the ITS sequences could separate S. rolfsii from the other two related species [43]. Hence, all the isolates obtained in the present study were identified as S. rolfsii on the basis of ITS sequence analysis.

Phylogenetic data analysis and their placement confirmed that the LSU sequences of 13 different isolates of Sclerotium species isolated from sweetpotatoes in Korea and their reference species obtained from GenBank produced three distinctive groups, represented as S1, S2, and S3; the isolates from the present study belonged to the group S3. Three morphologically similar species, i.e., S. rolfsii, S. delphinii, and S. coffeicola, were grouped into S3. Xu [17] explained that these three species are phylogenetically and morphologically very similar and produce similar clades in phylogenetic analysis [45,46]. In group S3, there were three subgroups, for which the present study isolates formed separate subgroups, and the three reference sequences of S. delphinii and two reference sequences of S. coffeicola were separated from A. rolfsii (teleomorph: S. rolfsii) and from each other with a high bootstrap value. All of the ITS sequences showed similar results in the molecular data analysis. Thus, the molecular identification supported the morphological observations.

Irani et al. [47] tested the pathogenicity of S. sclerotiorum on detached rapeseed and found variations in pathogenicity and aggressiveness. Adandonon et al. [43] evaluated pathogenicity on cowpea and showed variations in pathogenicity and aggressiveness in Benin and South Africa. Our pathogenicity study revealed that there might present different races of S. rolfsii in Korean sweetpotato isolates. Our further study would focus on the races. Thus, along with these previous studies, our current results suggested that morphological characteristics along with molecular phylogenetic analysis are useful tools to identify and distinguish Sclerotium species.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Basic Research Program (project no. PJ011327012016) funded by the Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Loebenstein G, Thottappilly G. The sweet potato. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregory P. Feeding tomorrow's hungry: the role of root and tuber crops. In: Hill WA, Bonsi CK, Loretan PA, editors. Sweet potato technology for the 21st century. Tuskegee (AL): Tuskegee University Press; 1992. pp. 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottema T. Rapid market appraisal, issues and experience with sweet potato in Vietnam. In: Scott G, Wiersema S, Ferguson PI, editors. Product development for root and tuber crops. Lima: International Potato Center; 1992. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott GJ, Rosegrant MW, Ringler C. Roots and tubers for the 21st century: trends, projections, and policy options. Food, agriculture, and the environment, discussion paper 31. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwak HR, Kim MK, Shin JC, Lee YJ, Seo JK, Lee HU, Jung MN, Kim SH, Choi HS. The current incidence of viral disease in Korean sweet potatoes and development of Multiplex RT-PCR assays for simultaneous detection of eight sweetpotato viruses. Plant Pathol J. 2014;30:416–424. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.04.2014.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie C. Mycelial compatibility and pathogenic diversity among Sclerotium rolfsii isolates in southeastern United States [thesis] Gainesville (FL): University of Florida; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aycock R. Stem rot and other diseases caused by Sclerotium rolfsii or the status of Rolfs' fungus after 70 years. Raleigh (NC): North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station; 1996. pp. 132–202. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farr DF, Bills GF, Chamuris GP, Rossaman AY. Fungi on plants and plant products in the United States. St. Paul (MN): APS Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullen J. Southern blight, southern stem blight, white mold. Plant Health Instr. 2001 doi: 10.1094/PHII-2001-0104-01. [Epub] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahadevakumar S, Yadav V, Tejaswini GS, Janardhana GR. Morphological and molecular characterization of Sclerotium rolfsii associated with fruit rot of Cucurbita maxima. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2016;145:215–219. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Punja ZK. The biology, ecology and control of Sclerotium rolfsii. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1985;23:97–127. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald BA, McDermott JM. Population genetics of plant pathogenic fungi. Bioscience. 1993;43:311–319. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruns TD, White TJ, Taylor JW. Fungal molecular systematics. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1991;22:525–564. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okabe I, Arakawa M, Masumoto N. ITS polymorphism within a single strain of Sclerotium rolfsii. Mycoscience. 2001;42:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tyson JL, Ridgway HJ, Fullerton RA, Stewart A. Genetic diversity in New Zealand populations of Sclerotium cepivorum. N Z J Crop Hort Sci. 2002;30:37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harlton C. Genetic diversity and variation in Sclerotium (Athelia) rolfsii and related species [thesis] Burnaby: Simon Fraser University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Z. Overwinter survival of Sclerotium rolfsii and S. rolfsii var. delphinii, screening hosta for resistance to S. rolfsii var. delphinii, and phylogenetic relationships among Sclerotium species [dissertation] Ames (IW): Iowa State University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teng PS, James WC. Disease and yield loss assessment. In: Waller JM, Lenne JM, Waller SJ, editors. Plant pathologist's pocket book. London: CABI Publishing; 2001. pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul NC, Kim WK, Woo SK, Park MS, Yu SH. Fungal endophytes in roots of Aralia species and their antifungal activity. Plant Pathol J. 2007;23:287–294. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rayner RW. mycological colour chart. Surrey: Commonwealth Mycological Institute; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 21.White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfard DH, Shinsky JJ, White TJ, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. New York: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vilgalys R, Hester M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4238–4246. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4238-4246.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chun J. Computer-assisted classification and identification of actinomycetes [dissertation] Newcastle upon Tyne: University of Newcastle; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul NC, Lee HB, Lee JH, Shin KS, Ryu TH, Kwon HR, Kim YK, Youn YN, Yu SH. Endophytic fungi from Lycium chinense Mill and characterization of two new Korean records of Colletotrichum. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:15272–15286. doi: 10.3390/ijms150915272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JH, Kim SC, Cheong SS, Choi KH, Kim DY, Shim HS, Lee WH. Stem rot of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) caused by Sclerotium rolfsii in Korea. Res Plant Dis. 2013;19:118–120. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwon JH, Park CS. Stem rot of tomato caused by Sclerotium rolfsii in Korea. Mycobiology. 2002;30:244–246. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrieri R, Cozzolino E, Tarantino P, Cerrato D, Lahoz E. First report of southern blight on candyleaf (Stevia rebaudiana) caused by Sclerotium rolfsii in Italy. Plant Dis. 2016;100:220. [Google Scholar]

- 31.You JM, Liu H, Huang BJ. First report of southern blight caused by Sclerotium rolfsii on Mecleaya cordata in China. Plant Dis. 2016;100:530. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahadevakumar S, Tejaswini GS, Janardhana GR, Yadav V. First report of Sclerotium rolfsii causing southern blight and leaf spot on common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) in India. Plant Dis. 2015;99:1280. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahadevakumar S, Janardhana GR. Morphological and molecular characterization of Sclerotium rolfsii associated with leaf blight disease of Psychotria nervosa (wild coffee) J Plant Pathol. 2016;98:351–354. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akram M, Saabale PR, Kumar A, Chattopadhyay C. Morphological, cultural and genetic variability among Indian populations of Sclerotium rolfsii. J Food Leg. 2015;28:330–334. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Punja ZK, Grogan RG. Hyphan interactions and antagonism among field isolates and single-basidiospore strains of Athelia (Sclerotium) rolfsii. Phytopathology. 1983;73:1279–1284. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harlton CE, Lévesque CA, Punja ZK. Genetic diversity in Sclerotium (Athelia) rolfsii and related species. Mol Plant Pathol. 1995;85:1269–1281. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon JH, Lee HS, Kang DW, Kwack YB. Stem rot of Convallaria keiskei caused by Sclerotium rolfsii. Kor J Mycol. 2011;39:145–147. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwon JH, Kang DW, Lee HS, Choi SL, Lee SD, Cho HS. Occurrence of Sclerotium rot of corn caused by Sclerotium rolfsii in Korea. Korean J Mycol. 2013;41:197–199. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwon JH, Park CS. Stem rot of Capsicum annuum caused by Sclerotium rolfsii in Korea. Res Plant Dis. 2004;10:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwon JH. Stem rot of garlic (Allium sativum) caused by Sclerotium rolfsii. Mycobiology. 2010;38:156–158. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2010.38.2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Punja ZK, Damiani A. Comparative growth, morphology and physiology of three Sclerotium species. Mycologia. 1996;88:694–706. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murdue JE. CMI descriptions of pathogenic fungi and bacteria. No. 410. Surrey: Commonwealth Mycological Institute; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adandonon A, Aveling TA, van der, Sanders G. Genetic variation among Sclerotium isolates from Benin and South Africa, determined using mycelial compatibility and ITS rDNA sequence data. Aust Plant Pathol. 2005;34:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okabe I, Matsumoto N. Phylogenetic relationship of Sclerotium rolfsii (teleomorph Athelia rolfsii) and S. dolphinii based on ITS sequences. Mycol Res. 2003;107(Pt 2):164–168. doi: 10.1017/s0953756203007160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Punja ZK, Sun LJ. Genetic diversity among mycelial compatibility groups of Sclerotium rolfsii (teleomorph Athelia rolfsii) and S. delphinii. Mycol Res. 2001;105:537–546. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu Z, Harrington TC, Gleason ML, Batzer JC. Phylogenetic placement of plant pathogenic Sclerotium species among teleomorph genera. Mycologia. 2010;102:337–346. doi: 10.3852/08-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Irani H, Heydari A, Javan-Nikkhah M, Ibrahimov AS. Pathogenicity variation and mycelial compatability groups in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. J Plant Prot Res. 2011;51:329–336. [Google Scholar]