Abstract

RATIONALE

High-throughput metabolomics has now made it possible for small/medium-sized laboratories to analyze thousands of samples/year from the most diverse biological matrices including biofluids, cell and tissue extracts. In large scale metabolomics studies, stable isotope-labeled standards are increasingly used to normalize for matrix effects and control for technical reproducibility (e.g. extraction efficiency, chromatographic retention times and mass spectrometry signal stability). However, it is currently unknown how stable mixes of commercially-available standards are following repeated freeze/thaw cycles or prolonged storage of aliquots.

METHODS

Standard mixes for 13C, 15N or deuterated isotopologues of amino acids and key metabolites from the central carbon and nitrogen pathways (e.g. glycolysis, Krebs cycle, redox homeostasis, purines) were either repeatedly frozen/thawed for up to 10 cycles, or diluted into aliquots prior to frozen storage for up to 42 days. Samples were characterized by ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to determine the stability of the aliquoted standards upon freezing/thawing or prolonged storage.

RESULTS

Metabolite standards were stable over up to 10 freeze/thaw cycles, with the exception of adenosine and glutathione, showing technical variability across aliquots in a freeze/thaw-cycle-independent fashion. Storage for up to 42 days of mixes of commercially available standards did not significantly affect the stability of amino acid or metabolite standards for the first two weeks, while progressive degradation (statistically-significant for fumarate) was observed after three weeks.

CONCLUSIONS

Refrigerated or frozen preservation for at least 2 weeks of aliquoted heavy-labeled standard mixes for metabolomics analysis is a feasible and time-/resource-saving strategy for standard metabolomics laboratories.

Keywords: Mass spectrometry, standard stability

Introduction

Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics has recently contributed great strides in biomedical research,[1] influencing the most diverse fields from pulmonology[2] to immunology,[3], from cancer research [4] to intensive care medicine[5] and sports physiology.[6] Technological advancements in the field of mass spectrometry (MS)-based metabolomics have made it cost affordable for small/middle-sized metabolomics centers to serve hundreds of investigators on a yearly basis, fostering a new era in the field of omics disciplines and their translational relevance to basic science and clinical applications. High-throughput workflows based on flow-injection MS[7] or ultra-high throughput liquid-chromatography[8,9] have made a significant portion of the metabolome amenable to detection and quantification of over 10,000 features and hundreds of named metabolites in less than three minutes. Optimization of rapid extraction protocols,[10] automatization[11] and, predictably, low-cost robotization of sample extraction protocols[12] would enable affordable processing of hundreds to a thousand samples per day in a cost-effective manner. Such advancements will also likely help bridging the reproducibility/inter-laboratory standardization gap between research laboratory and clinical laboratories, paving the way for the establishment of the long-anticipated field of clinical metabolomics.[13] In this view, it is worth noting that high-throughput metabolomics methods are relevant to (biomarker) discovery studies, but also for their validation. Indeed, the characterization of clinically-relevant metabolic biomarkers requires a final validation phase in large prospective cohorts, which is dependent upon the establishment of high-throughput quantitative workflows that make such cohorts amenable to metabolic phenotyping. For example, high-throughput metabolomics approaches can be theoretically used to dose metabolic markers of inborn errors of metabolism such as homocysteine[14], diabetes such as glucose,[15] or acid-base-deficit and tissue hypoxia in trauma such as lactic acid[16] and succinate[17]. While targeted approaches based on multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) MS have been historically adopted in the clinical setting[18], recent technological advancements in the field of MS through high resolution quadrupole-orbitrap-based instruments have afforded investigators to simultaneously perform untargeted metabolomics analyses while post-hoc quantitatively targeting specific metabolites of interest. Borrowing from MS-based quantitative proteomics approaches such as AQUA[19] or QconCAT[20], the use of stable isotope-labeled internal standards has been increasingly adopted in the field of metabolomics in that it allows monitoring for quality control parameters such as extraction efficiency, reproducibility of chromatographic retention times and MS signal intensity. At the same time, quantification of the same compounds in different biological matrices or inter-laboratory reproducibility of quantitative results from different instruments of the same sample sets is eased by the use of stable isotope-labeled standards, in that they help normalizing for matrix effects (e.g. ion suppression) or instrument-dependent variability across platforms, provided the concentrations of the labeled standards and the endogenous metabolite from the tested matrix are within the linearity range of the MS instrument. Finally, stable isotope-labeled standards can be used to obtain quantitative information on metabolic fluxes through direct comparison against isotopologues deriving from alternative metabolism of stable heavy isotope tracers, as we showed recently for lactate[21] and alanine[22] synthesis downstream to 13C1,2,3-glucose catabolism via glycolysis or the pentose phosphate pathway in red blood cells.

On a project-dependent basis, standard mixes are generated and aliquoted at concentrations relevant for the specific matrix to be analyzed (e.g. plasma, cell extracts, etc). Despite all the above-mentioned advantages associated with the use of stable isotope labeled standards in metabolomics, the stability of these compounds during prolonged frozen storage or upon repeated freeze/thaw cycles has not been characterized yet. This is relevant in that the average time necessary to prepare a standard mix containing a minimum of two heavy labeled standards is ~15 min. At an average of 10 experiments per week in our metabolomics lab, this adds up to ~245 bench time work hours/year, costing up to 16,000$ of personnel time and revenue loss for a small-sized metabolomics laboratory. Understanding the stability of aliquoted standard mixes would abate these costs and positive impact the affordability of the use of heavy labeled internal standards for routine metabolomics applications in smaller laboratories.

Materials and Methods

Standards and solvents

All reagents were purchased from SIGMA Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Standards were purchased from SIGMA Aldrich or Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc. (Tewksbury, MA, USA). Heavy labeled standards mixes were generated, including 17 uniformly 13C15N-amino acids at a final concentration of 2.5 μM, and additional 11 standard metabolites including 13C1-lactate (40 μM), 1,1,2,2-D-choline and 9-D-trimethylamine N-oxide (1 μM), and 2,2,4,4-D-citrate, 13C5-2-oxoglutarate, 13C4-succinate, 13C1,4-fumarate, 13C6-glucose, and 13C215N1-Glutathione (heavy glycine-GSH), 13C5-adenosine and dimethylglycine at a final concentration of 5 μM (Cambridge Isotopes Laboratories, Inc., Tewksbury, MA – detailed information about the standards are provided in Supplementary Table 1).

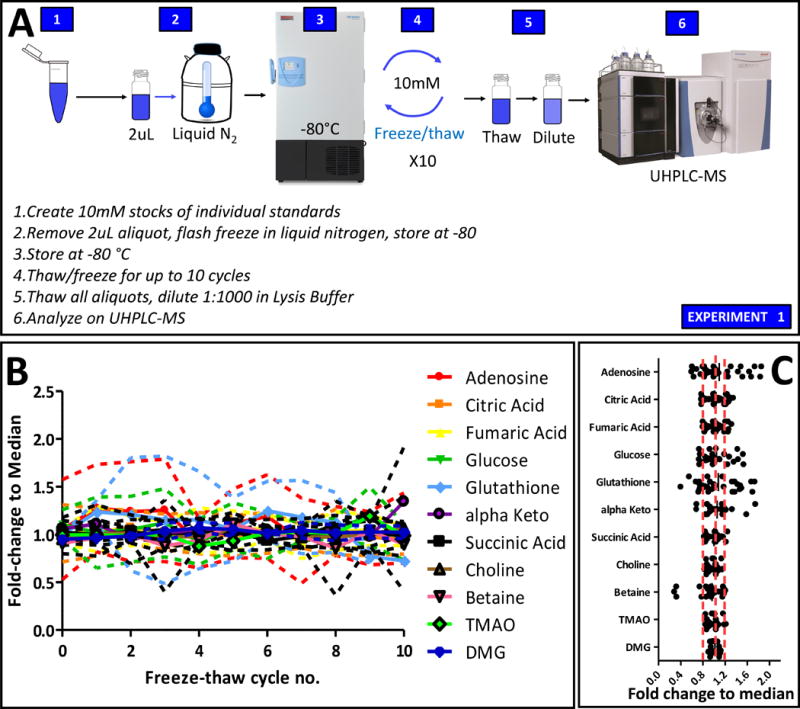

Experiment 1 – Standard mix stability as a function of freeze/thaw cycles

To characterize the effect of freeze/thaw cycles on standard mixes, 10 mM aliquots were frozen at −80°C and thawed multiple times (for up to 10 times). After thawing, aliquots were diluted 1:1000, in order for the standard concentrations to be within biologically-relevant thresholds for commonly tested matrices in our lab (e.g. plasma, blood, cell extracts), as previously noted.[10] These concentrations fall within the linearity range of the instrument, as previously tested.[8,23]

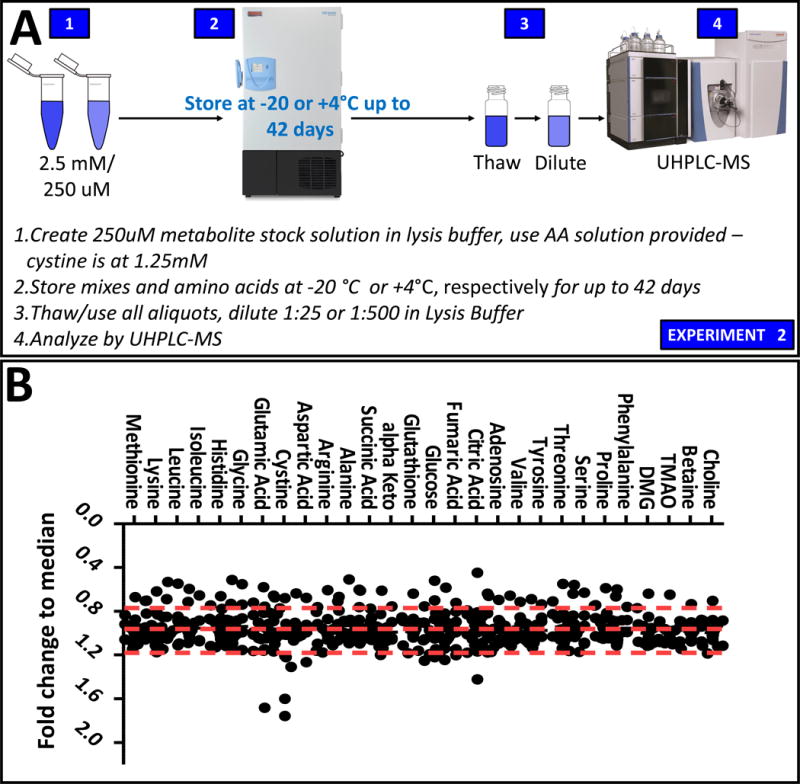

Experiment 2 – Standard mix stability as a function of refrigerated/frozen storage duration

To characterize the effects of storage duration, a standard mix was created from commercially available standards to achieve final concentrations of 250μM, prior to storage at −20°C (the standard storage and utilization temperature for the lysis buffer in our workflow[8,23]) for 3, 7, 14, 21, 28 and 42 days. Additionally, a 1:10 dilution of a commercially available mix of uniformly 13C15N-amino acids were stored at +4°C per manufacturer instructions for 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 42 days. After thawing, aliquots were diluted 1:25 or 1:50, respectively, for the standard concentrations to be within biologically-relevant thresholds for commonly tested matrices in our lab (e.g. plasma, blood, cell extracts), as previously noted.[10] These concentrations fall within the linearity range of the instrument, as previously tested.[8,23]

UHPLC-MS metabolomics analysis

Sample extracts were processed through UHPLC-MS, as previously reported[8]. Briefly, analyses were performed on a Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) coupled online to a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany), as previously reported. Samples were resolved over a Kinetex C18 column, 2.1 × 150 mm, 1.7 μm particle size (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) at 25 °C using an isocratic condition of 5% acetonitrile, 95% water, flowed at 250 μl/min. Solvents for positive mode runs contained 0.1% (v/v) formic acid; solvents for negative mode runs contained NH4OAc (5 mM). The mass spectrometer was operated independently in positive or negative ion mode scanning in Full MS mode (2 μscans) at 60,000 resolution from 60 to 900 m/z, with electrospray ionization operating at 4 kV spray voltage, 15 shealth gas, 5 auxiliary gas. Calibration was performed prior to analysis using the Pierce™ Positive and Negative Ion Calibration Solutions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Acquired data was converted from. raw to. mzXML file format using Mass Matrix (Cleveland, OH, USA). Metabolite assignments, isotopologue distributions and correction for expected natural abundance of deuterium, 13C and 15N isotopes were performed using MAVEN (Princeton, NJ, USA)[24] and manual validation. Extensive information on the compounds monitored in this study is provided in the Supplementary data files.

Statistical Analysis

Graphs and statistical analyses (either T-Test or ANOVA) were performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA), Metaboanalyst 3.0[25] and GENE-E (Broad Institute, MA) were used to plot heat maps and principal component analyses (PCA). Coefficients of variation (CVs) were determined by calculating standard deviations divided by the mean of all measurements at any given freezing cycle (three replicates per cycle).

Results

Experiment 1 – Standard mix stability as a function of freeze/thaw cycles

An overview of the experimental workflow is provided in Figure 1.A. Briefly, standard mixes (composition detailed in Supplementary Table 1) were aliquoted prior undergoing repeated cycles of freezing and thawing and analysis by UHPLC-MS. Three aliquots were tested per freeze/thaw cycle and raw results are extensively reported in Supplementary Table 1. Since amino acid mixes are routinely stored under refrigerated conditions, as per vendor’s instructions, only metabolite standards compatible with freezing were tested in this experiment. CVs were determined across all tested aliquots, independently of freeze/thaw cycles. Results indicate that only adenosine, glutathione and betaine had CVs > 20% (Supplementary Table 1). Of note, two aliquots at freezing cycles 4 and 9 were the major contributors to the observed deviations (Supplementary Table 1). Despite technical variability observed across repeated measures and cycles, no significant cycle-dependent increase/decrease was observed, as further confirmed by Principal Component Analysis (PCA – Supplementary Figure 1.A). Most standards were not influenced by freeze/thaw cycles and remained stable (0.8<fold-change <1.1 from median values in all the aliquots tested (Figure 1.B), with the exception of adenosine, glutathione, glucose and α-ketoglutarate, that differed significantly from the median in up to one measurement per cycle (adenosine – Figure 1.C). Since the samples were run in a randomized order, this observation is not attributable to the influence of instrument signal instability (TIC variability <6% through the whole analysis). Three outliers were detected for betaine in a single aliquot at cycles 4, 6 and 10 – suggesting a technical variability not attributable to freeze/thaw cycles. Four metabolites changed significantly in standards mixes that had undergone 10 freeze/thaw cycles, though of those only α-ketoglutarate showed 0.8 > fold changes > 1.2, while the rest was comparable to the median values measured in fresh never frozen/thawed standards (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1. Freeze/thaw cycles and stable isotope standard mixes.

An overview of the experimental workflow is provided in A. In B, deviation from median measurements for each standard metabolite in all tested sample following up to 10 cycles of freeze/thaw. Median ± ranges are shown in B, while single dot plots for each metabolite are reported in C.

Experiment 2 – Standard mix stability as a function of frozen storage duration

An overview of the experiment is provided in Figure 2.A. Prolonged storage at −20°C of standard mixes may represent a viable alternative to preparing mixes of heavy labeled standards for each new experiment. Here we stored 100 μl aliquots of heavy standard mixes (as detailed in Supplementary Table 1) for 3, 7, 14, 21, 28 and 42 days. Triplicate aliquots were tested per each storage day, in order to determine the stability of each tested standard. Results are extensively reported in Supplementary Table 1 and graphed in the form of ratios of fold-changes to the median (Figure 2.B). Even though technical variability was noted for the tested standards across replicates, no significant effect of storage duration was observed, as determined by PCA (Supplementary Figure 1.B). However, cystine showed major deviations from the median of measured values across all storage day in a storage time-independent fashion (Figure 2.B). Progressive loss of signal for heavy fumarate was observed after three weeks of frozen storage (fold-change <0.7; p-value=0.014 after two weeks of storage - Supplementary Table 1), suggesting that storage of a mix containing this compound for longer than two weeks may result in loss of accuracy in quantitation. Though not reaching significance, similar trends were observed for other carboxylic acids such as alpha-ketoglutarate and succinate and redox-sensitive glutathione (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. Storage of stable isotope standard mixes.

An overview of the experimental workflow is provided in A. In B, dot plot of triplicate measurement of stable isotope standard mixes over frozen storage for up to 42 days (fold-changes/medians are shown).

Discussion

Technical hurdles still persist with respect to standardization of quality control in high-throughput quantitative studies targeting specific classes of compounds. Recently, we described a high-throughput method for rapid quantitation of hydrophilic compounds from the central carbon and nitrogen pathways[8], including amino acids[23]. This method affords the rapid quantitation of tens to hundreds of named compounds from up to >450 samples/day, making it realistic to anticipate the potential translation of such technology into the field of clinical biochemistry. In this approach, the use of stable isotope internal standards affords correcting for matrix suppression effects, monitoring the stability of chromatographic peak shape and retention time as well as the stability of signal intensity at the MS level.[8]

Preparation of standard mixes to be used as internal standards for such studies can be time consuming for laboratories devoted to large scale metabolomics studies as well as core centers that provide metabolomics services for academic and industrial applications. At a minimum, we calculated a cost of ~$16k for the year-long repeated preparation of a standard mix including at least two different standards, costs that can easily scale up for more complex studies where tens to hundreds of heavy standards have to be mixed prior to sample extraction. Alternatives to the repeated preparation of mixes of stable isotope standards is the generation of a master mix or smaller aliquots to be frozen for weeks prior to thawing and usage. However, the effect of prolonged freeze/thaw cycles and frozen storage on the stability of metabolites in these mixes has not yet been described. In the present study we determined that mixes of commercially-available heavy-labeled standards are mostly stable over repeated freeze/thaw cycles, though some of the standards tend to gradually degrade over prolonged frozen storage. In particular, we noted that carboxylic acids (especially fumarate), adenosine and glutathione (a purine susceptible to deamination and a redox-sensitive tripeptide, respectively) tend to degrade over frozen storage when preserved as standard mixes for over 2 weeks at −20°C.

Our study is limited in that it only addresses the stability of hydrophilic standard compounds, those amenable to high-throughput analysis with the extraction protocols and UHPLC-MS workflow we previously characterized[8,10]. In the case of frozen storage experiments, aliquots were generated by dilution in lysis/extraction buffer (methanol:acetonitrile:water 5:3:2 v/v), a buffer rich in organic solvents and thus potentially responsible for the progressive loss in signal of carboxylic acids, that are commercially available dissolved in water. In addition, the present study does not address the long term effects of storage (e.g. one year or longer) on the stability of stable isotope-labeled standard mixes. Despite these limitations, the results suggest that most stable isotope compounds are resistant to repeated freeze/thaw cycles even when dissolved in relatively organic buffers and they can be safely stored with no significant loss in signal intensity for at least two weeks from the preparation of standard aliquots.

Conclusions

In this short technical note we characterized the stability of mixes of stable-isotope standards following freeze/thaw cycles and frozen storage. Overall, we observed no significant trend associated with the number of freeze/thaw cycles, while we suggest caution with prolonged storage of standard mixes containing carboxylic acids and redox sensitive glutathione or purines (adenosine) for longer than 14 days.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1 – Principal Component Analysis on the effect of freeze-thaw cycles (A) and frozen storage for up to 42 days (B) on the stability of stable isotope-standard mixes.

Supplementary Table 1 – Raw data and elaborations.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by funds from the Boettcher Webb-Waring Investigator Award (ADA), and the Shared Instrument grant by the National Institute of Health (S10OD021641) to KCH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest All the authors disclose no conflict of interests in relation to the contents of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kim SJ, Kim SH, Kim JH, Hwang S, Yoo HJ. Understanding Metabolomics in Biomedical Research. Endocrinol Metab Seoul Korea. 2016;31:7. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2016.31.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Alessandro A, Kasmi KEl, Plecita-Hlavata L, Jezek P, Li M, Zhang H, Gupte SA, Stenmark KR. Hallmarks of Pulmonary Hypertension: Mesenchymal and Inflammatory Cell Metabolic Reprogramming. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017 doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Neill LAJ, Kishton RJ, Rathmell J. A guide to immunometabolism for immunologists. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:553. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. The Emerging Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;23:27. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Alessandro A, Moore HB, Moore EE, Reisz JA, Wither MJ, Ghasabyan A, Chandler J, Silliman CC, Hansen KC, Banerjee A. Plasma succinate is a predictor of mortality in critically injured patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017 doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heaney LM, Deighton K, Suzuki T. Non-targeted metabolomics in sport and exercise science. J Sports Sci. 2017;1 doi: 10.1080/02640414.2017.1305122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zampieri M, Sekar K, Zamboni N, Sauer U. Frontiers of high-throughput metabolomics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2017;36:15. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nemkov T, Hansen KC, D’Alessandro A. A three-minute method for high-throughput quantitative metabolomics and quantitative tracing experiments of central carbon and nitrogen pathways. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom RCM. 2017;31:663. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis MR, Pearce JTM, Spagou K, Green M, Dona AC, Yuen AHY, David M, Berry DJ, Chappell K, Horneffer-van der Sluis V, Shaw R, Lovestone S, Elliott P, Shockcor J, et al. Development and Application of Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography-TOF MS for Precision Large Scale Urinary Metabolic Phenotyping. Anal Chem. 2016;88:9004. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gehrke S, Reisz JA, Nemkov T, Hansen KC, D’Alessandro A. Characterization of rapid extraction protocols for high-throughput metabolomics. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom RCM. 2017 doi: 10.1002/rcm.7916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dias DA, Koal T. Progress in Metabolomics Standardisation and its Significance in Future Clinical Laboratory Medicine. EJIFCC. 2016;27:331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liquid-handling Lego robots and experiments for STEM education and research. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001413. can be found under http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.2001413, n.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.D’Alessandro A, Giardina B, Gevi F, Timperio AM, Zolla L. Clinical Metabolomics: the next stage of clinical biochemistry. Blood Transfus. 2012;10:s19. doi: 10.2450/2012.005S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scolamiero E, Cozzolino C, Albano L, Ansalone A, Caterino M, Corbo G, di Girolamo MG, Di Stefano C, Durante A, Franzese G, Franzese I, Gallo G, Giliberti P, Ingenito L, et al. Targeted metabolomics in the expanded newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism. Mol Biosyst. 2015;11:1525. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00729h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, Singh GM, Cowan MJ, Paciorek CJ, Lin JK, Farzadfar F, Khang YH, Stevens GA, Rao M, Ali MK, Riley LM, Robinson CA, et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2·7 million participants. The Lancet. 2011;378:31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60679-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odom SR, Howell MD, Silva GS, Nielsen VM, Gupta A, Shapiro NI, Talmor D. Lactate clearance as a predictor of mortality in trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:999. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182858a3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lusczek ER, Muratore SL, Dubick MA, Beilman GJ. Assessment of key plasma metabolites in combat casualties. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82:309. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D’Alessandro A, Gevi F, Zolla L. A robust high resolution reversed-phase HPLC strategy to investigate various metabolic species in different biological models. Mol Biosyst. 2011;7:1024. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00274g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kettenbach AN, Rush J, Gerber SA. Absolute quantification of protein and post-translational modification abundance with stable isotope-labeled synthetic peptides. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pratt JM, Simpson DM, Doherty MK, Rivers J, Gaskell SJ, Beynon RJ. Multiplexed absolute quantification for proteomics using concatenated signature peptides encoded by QconCAT genes. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1029. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reisz JA, Wither MJ, Dzieciatkowska M, Nemkov T, Issaian A, Yoshida T, Dunham AJ, Hill RC, Hansen KC, D’Alessandro A. Oxidative modifications of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase regulate metabolic reprogramming of stored red blood cells. Blood. 2016;128:e32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-714816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’alessandro A, Dzieciatkowska M, Nemkov T, Hansen KC. Red blood cell proteomics update: is there more to discover? Blood Transfus Trasfus Sangue. 2017;15:182. doi: 10.2450/2017.0293-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nemkov T, D’Alessandro A, Hansen KC. Three-minute method for amino acid analysis by UHPLC and high-resolution quadrupole orbitrap mass spectrometry. Amino Acids. 2015;47:2345. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-2019-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melamud E, Vastag L, Rabinowitz JD. Metabolomic Analysis and Visualization Engine for LC−MS Data. Anal Chem. 2010;82:9818. doi: 10.1021/ac1021166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia J, Sinelnikov IV, Han B, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst 3.0–making metabolomics more meaningful. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, Smith HO, Yandell M, Evans CA, Holt RA, Gocayne JD, Amanatides P, Ballew RM, Huson DH, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Putri SP, Yamamoto S, Tsugawa H, Fukusaki E. Current metabolomics: technological advances. J Biosci Bioeng. 2013;116:9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1 – Principal Component Analysis on the effect of freeze-thaw cycles (A) and frozen storage for up to 42 days (B) on the stability of stable isotope-standard mixes.

Supplementary Table 1 – Raw data and elaborations.