Abstract

Cortisol levels rise immediately after awakening and peak approximately 30-45 minutes thereafter. Psychosocial functioning influences this cortisol awakening response (CAR), but there is considerable heterogeneity in the literature. The current study used p-curve and metaanalysis on 709 findings from 212 studies to test the evidential value and estimate effect sizes of four sets of findings: those associating worse psychosocial functioning with higher or lower cortisol increase relative to the waking period (CARi) and to the output of the waking period (AUCw). All four sets of findings demonstrated evidential value. Psychosocial predictors explained 1%-3.6% of variance in CARi and AUCw responses. Based on these effect sizes, cross-sectional studies assessing CAR would need a minimum sample size of 617-783 to detect true effects with 80% power. Depression was linked to higher AUCw and posttraumatic stress to lower AUCw, whereas inconclusive results were obtained for predictor-specific effects on CARi. Suggestions for future CAR research are discussed.

The replication crisis in psychology has raised questions about the best methods to promote confidence in scientific findings. Some have suggested that “meta-analysis provides the best foundation for progress, even for messy applied questions” (Cumming, 2008, p. 292), because aggregating across studies reduces noise. Others have noted that publication bias and questionable research practices in individual studies can skew meta-analytic results (Simmons, Nelson, & Simonsohn, 2011), proposing additional ways to analyze the evidential value of a set of findings (Simonsohn, Nelson, & Simmons, 2014; van Aert, Wicherts, & van Assen, 2016). Research on relations between hormones and behavior can be particularly “messy” and vulnerable to inconsistency. The literature on psychosocial functioning and the cortisol awakening response (CAR) has more than doubled in the last six years, but heterogeneity in published findings has partially obscured the nature and direction of these effects. The present study aims to assess the evidential value of the published literature linking psychosocial functioning to the CAR.

Cortisol is a steroid hormone involved in glucose regulation and metabolism that is frequently labeled a stress hormone because its levels change markedly in response to stressors (see Sapolsky, 2004 for a review). Cortisol levels rise steeply immediately after awakening in the morning and peak approximately 30-45 minutes thereafter; from there, they slowly decrease throughout the day. This early peak in cortisol is known as the CAR (Pruessner, 1997). The CAR is responsive to stress perception and anticipation of daily stressors, making it particularly interesting to psychologists (Fries, Dettenborn, & Kirschbaum, 2009).

A meta-analysis of 62 studies revealed considerable heterogeneity in findings linking psychosocial functioning to the CAR (Chida & Steptoe, 2009). For instance, CAR measures were negatively correlated with depression in one study (O'Donnell et al., 2008) but positively correlated in another (Mommersteeg et al., 2006). Heterogeneity in the literature linking psychosocial functioning to the CAR is the rule rather than the exception; in fact, in four of seven types of psychosocial predictors, studies showing both positive and negative associations exist (Chida & Steptoe, 2009). Heterogeneity may result from inconsistency in how the CAR is measured (Stadler et al., 2016) and from small sample sizes (N < 100) that are characteristic of the literature. With small sample sizes, observed effects may misestimate both the size and the direction of any true underlying effect (Gelman & Carlin, 2014). Misestimations of direction are unlikely to be detected because there are no norms for the CAR, making it impossible to tell whether CAR values represent hyporesponsiveness, normal responses, or hyperresponsiveness.

To further complicate matters, different researchers operationalize and measure the CAR differently. Most researchers quantify the dynamic increases that occur during the first waking hour (CARi). Others compute the area under the curve relative to the waking period (AUCw) to quantify total cortisol output, although this is not strictly a measure of CAR because it is influenced by cortisol levels prior to awakening and not entirely by dynamic increases in cortisol that happen post-wakening (Stadler et al., 2016). In studies in which both CARi and AUCw were measured, their relationships to measures of psychosocial functioning were not the same (e.g., Bhattacharyya et al., 2008; Chida & Steptoe, 2009; Ellenbogen et al., 2006; Mommersteeg et al., 2006; Sonnenschein et al., 2007; Whitehead et al., 2007), suggesting possible measure-dependent effects.

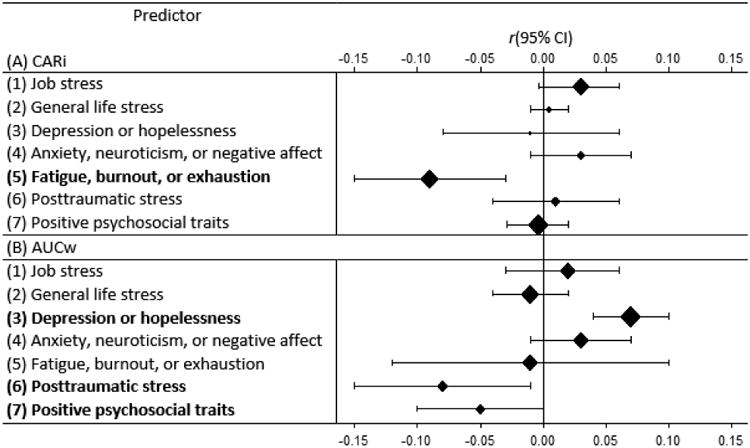

Yet another source of heterogeneity in the literature emerges from specific subytpes of psychosocial predictors having unique associations with the CAR. Chida and Steptoe (2009) described seven different types of psychosocial predictors: job stress, general life stress (non-work-related), depression, anxiety (including neuroticism and negative affect), fatigue/burnout/exhaustion, posttraumatic stress, and positive psychosocial traits. These different predictors may have different relationships with the CAR. For example, AUCw was positively related to general life stress but negatively related to posttraumatic stress (Chida & Steptoe, 2009). Similarly, CARi was positively correlated with job stress and general life stress but negatively correlated with fatigue, burnout, or exhaustion and not reliably associated with positive affect. Meta-analytic findings, therefore, suggest that psychosocial predictors can be related to higher or lower CAR, depending on the nature of the predictor.

Meta-analysis is designed to aggregate across individual findings and extract the commonalities from the idiosyncrasies. The latest meta-analysis on psychosocial functioning and CAR was a step in the right direction (Chida & Steptoe, 2009). However, a potential problem with meta-analysis is the file drawer problem, where studies are “filed away” unpublished if they fail to find statistically significant relationships. When studies are statistically significant, they make their way into the literature. Over time, this practice artificially inflates Type I error and may make it appear that relationships exist when in reality they do not (Rosenthal et al., 1979). To the degree that a meta-analysis includes a disproportionate number of Type I errors, its results – although superior to individual findings – may nonetheless be biased.

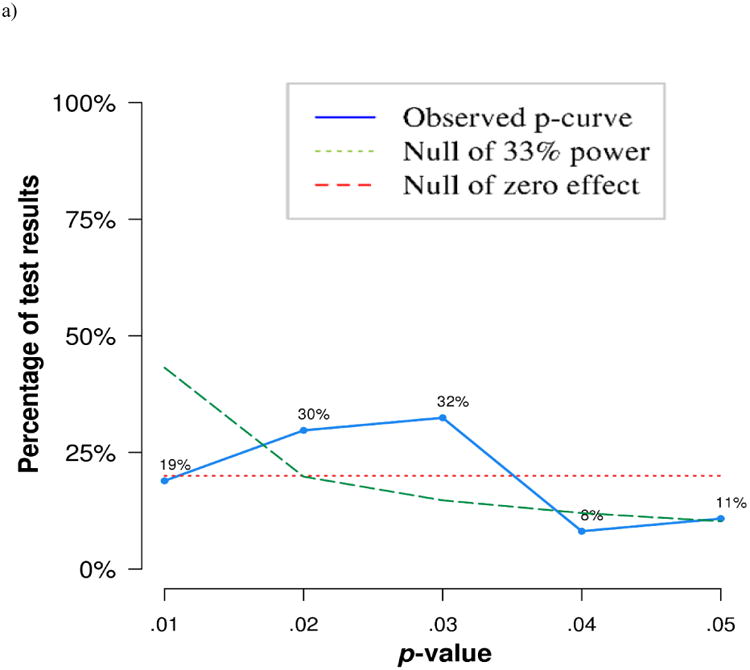

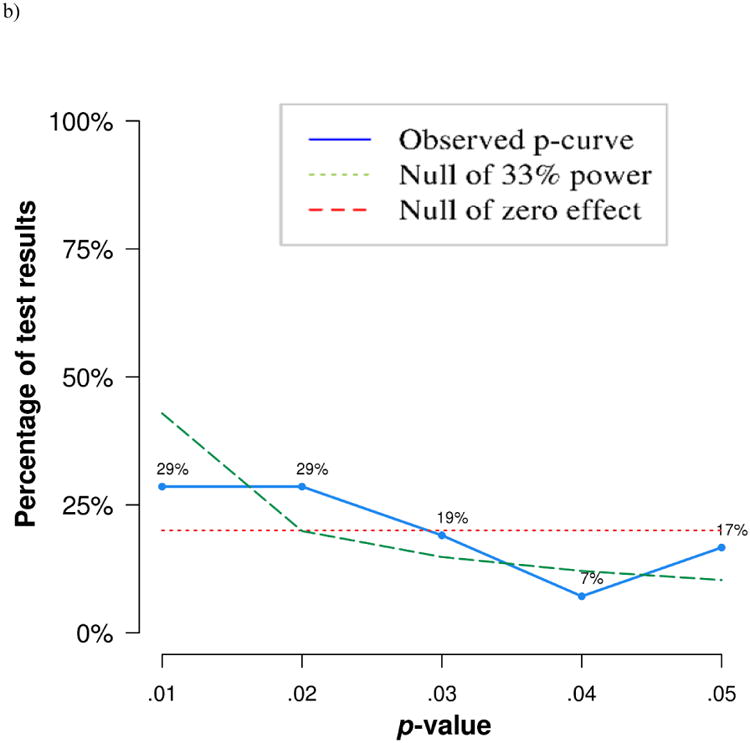

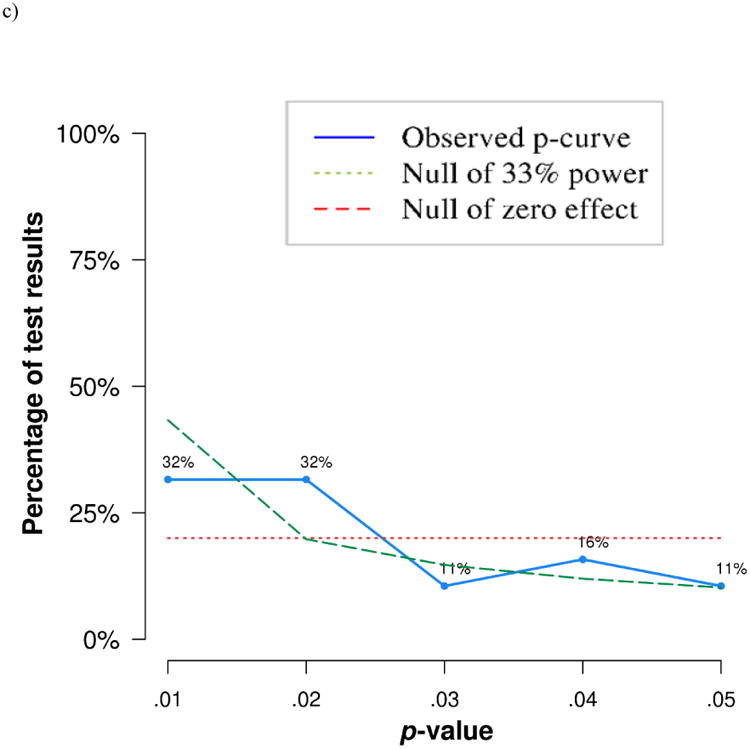

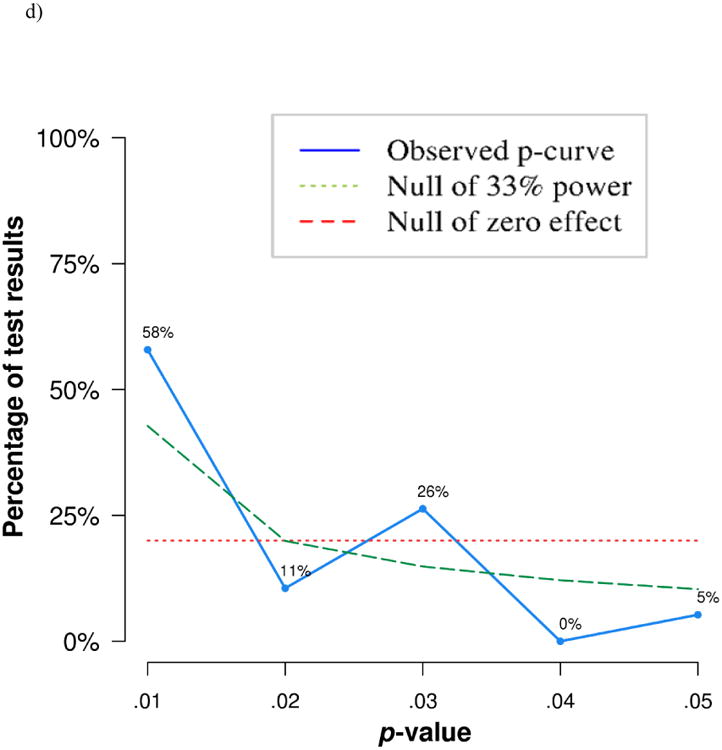

New statistical tools allow researchers to test a set of findings for evidential value in less biased ways. Specifically, p-curve analysis is based on the mathematical principle that if the null hypothesis is true, the probability of a p-value falling within a range of possible values is the same for all bins of the same size (Simonsohn, Nelson, & Simmons, 2014a, 2014b, 2015). Thus, given that the null hypothesis is true (i.e., studies lack evidential value), the probability of p falling between .01 - .02 is equal to the probability of it falling between .02 - .03, .03 -.04, or .04 - .05. In this case, a curve of all the significant p-values within a set of findings (i.e., a p-curve) will be flat. However, if a set of findings contains evidential value, more significant p-values from that set will fall in the .01 - .02 and .02 - .03 bins than in the .03 - .04 and .04 - .05 bins, and the p-curve will be positively skewed. Thus, by assembling the p-values for any set of significant findings and calculating the slope of that line, evidential value can be determined (Simonsohn et al., 2014a, 2014b, 2015). Moreover, if one knows all the p-values from a set of findings, one can approximate the distribution used to obtain those p-values, resulting in an unbiased estimate of effect size (Simonsohn et al., 2014a). This point estimate can then be compared to a meta-analytic point estimate to assess for systematic bias in the literature.

The Current Study

Although the extant literature suggests that psychosocial functioning and the CAR are associated, the nature of these associations remains unclear. In some studies, psychosocial variables were related to higher CAR and in other studies, to lower CAR (Chida & Steptoe, 2009). Moreover, the relationship between psychosocial functioning and the CAR may not be the same for different measures of the CAR, and may not be consistent for all psychosocial predictors. The current study aims to clarify the following questions regarding the relationships between psychosocial functioning and the CAR by combining p-curve and meta-analytic techniques: First, do the sets of findings associating psychosocial functioning to higher or lower CAR differ in evidential value? Second, what is the effect size for each of these sets of findings? Third, is there evidence of systematic bias in the extant literature? A secondary aim of the study was to examine predictor-specific effects.

Methods

Data Sources and Study Selection

The current study updated the literature testing relationships between psychosocial functioning and the CAR. It included studies previously reviewed by Chida and Steptoe (2009) and added new findings from the past six years. Methods for updating the literature were based on those described by Chida and Steptoe (2009). Articles were identified using the search terms “cortisol” and “awakening” and “response” simultaneously (thus allowing the terms to be out of order) using the Endnote X7.2 (Thompson Reuters) software to search across the following databases: Medline, PsycINFO, Pubmed, and Web of Science. The search terms were allowed to appear in “Any field” for the Pubmed and PsycINFO databases, or in “Title/Keywords/Abstract” for Web of Science and Medline. Articles that were duplicates across these databases, published in foreign language journals, dissertations, conference abstracts, and letters to the editor were removed at a first pass. Reference sections of the identified articles were searched for other relevant articles. To avoid overlap with the previous meta-analysis, the search dates for the updated literature were restricted to articles published between October 1, 2008 and July 1, 2015. Inclusion criteria required articles to (1) be written in English, (2) be published in a peer-reviewed journal, (3) include at least one measure of psychosocial functioning, and (4) include at least one measure of the CAR. Articles were excluded if the population of interest had medical conditions/disorders known to influence cortisol, including pregnant or post-partum women, chronic pain disorders, circadian rhythm disorders, endocrine disorders, hormonal treatments, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or other medical conditions. Biological predictors of the CAR (genetics or gene × environment interactions, family history of psychopathology, sleep patterns and disorders, chronotype), as well as intervention studies or effects of laboratory manipulations, were also excluded. Studies including participants with intellectual or developmental disabilities, dementia, or other cognitive impairments were excluded because there was insufficient research to synthesize these studies separately. Lastly, studies focusing on within-subject psychosocial changes were excluded because the current study focused on individual differences instead of intraindividual shifts, and there has recently been a thorough review on within-subject effects on the CAR (Law, Hucklebridge, Thorn, Evans, & Clow, 2013).

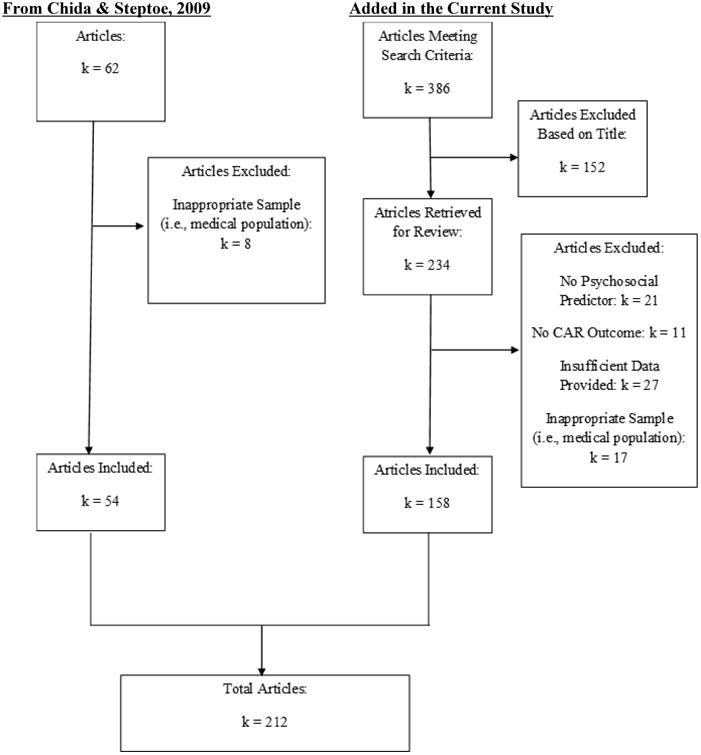

Where different articles reported on the same cohort (e.g., from large publicly available datasets), they were treated as multiple findings from the same study. In cases where articles met inclusion criteria but provided insufficient data for analysis, the corresponding authors were contacted. Of 32 authors contacted, 19 responded, and 17 provided additional data. In total, 159 articles met criteria for the updated literature review. These were combined with 54 articles from the Chida and Steptoe (2009) analysis. Thus, the current study included 709 findings from 212 articles. Figure 1 provides a flowchart of the included articles.

Figure 1. Flow Chart of Articles Included in Study.

Data Abstraction

The following information was abstracted for each article added in the current study: title, author, publication year, sample size, psychosocial predictor measurement method, CAR formula used, test statistic, statistic pertaining to psychosocial functioning/CAR relationship, and information to compute quality score (described below). Suitable formulas for CARi included the mean cortisol value post-awakening minus the wakening value (MINC), the absolute increase in cortisol as indexed by the maximum value minus the minimum value (AINC), the absolute cortisol values where the effect size was assessed through repeated-measures analysis (ACOR), the slope of the CAR curve (slope), or the ratio of cortisol values at wakening to 30 minutes post wakening (T0/T1 ratio). For AUCw, the overall volume of cortisol released during the waking period as indexed by the total area under the curve was used.

A quality score for each study was computed based on whether the studies controlled for each of the following: (1) age, (2) gender, (3) smoking status, (4) medications that influenced cortisol, (5) weekday versus weekend collection days (6) waking time, and (7) adherence to protocol. Moreover, (8) clear instructions for collection had to be provided to participants. A point was awarded for each of these eight criteria that was explicitly described in the article, leading to a total research quality score ranging from 0 to 8. Data abstraction for the articles in the current study was done by one of the first three authors (IB, CH, EH) and double-checked by another of these authors. A randomly selected subset of 15 articles were independently coded by all three authors, and there was high corroboration on the data that were extracted (>90% agreement on each variable). Discrepancies were settled by group discussions among authors. For articles published before 2009, data were drawn from the Chida and Steptoe (2009) meta-analysis (Table 1, pp. 268-272).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Findings in Meta-Analysis.

| Number of Articles | 212 |

| Number of Findings | 709 |

| Number of Independent Findings | 186 |

| Mean Sample Size of Studies | 244.95 (SD: 520.68; Med: 74; Range: 11 – 4,364) |

| Mean Number of Days Sampled | 2.04 (SD: 1.31; Med: 2; Range: 1 – 9) |

| Mean Quality Score of Studies | 6.08 (SD: 1.64; Med: 6; Range: 1 – 8) |

| Total Number of Findings for each Predictor Type | |

| Job Stress | 64 |

| General Life Stress | 221 |

| Depression | 118 |

| Anxiety/Neuroticism/Negative Affect | 91 |

| Fatigue/Burnout/Exhaustion | 37 |

| Posttraumatic Stress | 56 |

| Positive Psychosocial Traits | 122 |

Data Analysis

To test for evidential value, p-curves were computed for the following four sets of associations: (1) worse psychosocial functioning with higher CARi, (2) worse psychosocial functioning with lower CARi, (3) worse psychosocial functioning with higher AUCw, and (4) worse psychosocial functioning with lower AUCw. A p-curve-derived estimate of effect size was computed from each of the four p-curves. Next, meta-analysis was used to estimate effects for these four categories, and these meta-analytic estimates were compared to the p-curve-derived estimate of effect size. Details for these procedures are discussed below.

P-curve analysis for evidential value

To compute p-curves, directionality for all predictors was changed so that higher values reflected worse psychosocial functioning. P-curve analyses requires that all findings be independent of one another. If more than one significant relationship was reported from the same sample, or if samples were partially overlapping (i.e., females only in one effect, and males and females in another), the effect with the largest sample size was chosen for inclusion in the p-curve. T-values and degrees of freedom (n-2) from significant findings were entered into a publicly available p-curve calculator provided by Simonsohn and colleagues (2013; Version 4.05; http://www.p-curve.com/). To test for evidential value, the p-curve calculator estimated the probability of obtaining that p-value if the null were true. Flat curves (neither right nor left skewed) indicated that findings lacked evidential value or were underpowered to detect evidential value. These alternatives were differentiated by testing the set of findings against a null of 33% power as outlined by Simonsohn et al. (2014); if significant, findings could be assumed to lack evidential value; otherwise, evidential value could not be confirmed or denied.

P-curve analysis for estimates of effect size

Using R syntax, significant p-values of a set of findings were used to estimate the effect size of those findings (see Simonsohn et al., 2014b for the syntax). P-curve-derived effect size estimates for each of the four sets of findings were computed. Only significant, findings could be assumed findings from independent samples were entered. Effect sizes were computed in Cohen's d and were then converted into r using the formula r = d/√(d2 +4).

Meta-analysis

Methods described by Chida and Steptoe (2009) were followed to allow for the aggregation of their findings with findings retrieved for the current study. Meta-analytic estimate of effect sizes were transformed into the correlation coefficient r. When multiple estimates of the same correlation were provided, associations adjusted for covariates were included. Bivariate correlations were used when there was no covariate adjustment for analyses involving the CAR, or when there was insufficient information to extract an effect size from the covariate-adjusted analyses. Because variance of correlation coefficients depended strongly on sample size (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009), the r values derived from each study were transformed to Fisher's z and analyses were conducted on these values. The z values were later back-transformed into r values to facilitate interpretation of the meta-analytic findings.

The effect sizes were aggregated using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 2.2.064. Each random-effects model yielded an aggregate weighted effect size r ranging in value from -1.00 to 1.00, interpreted the same way as a correlation coefficient. Each r statistic was weighted before aggregation by multiplying its value by the inverse of its variance; this procedure enabled larger studies to contribute to effect size estimates to a greater extent than smaller ones. 95% confidence intervals were computed to assess whether aggregate effect sizes were statistically significant. A heterogeneity coefficient was used to determine whether the studies yielded consistent findings. Publication bias was assessed using Egger's unweighted regression asymmetry test, which tests the asymmetry of the funnel plot of effect sizes plotted by sample size (Egger, Smith, Schneider, & Minder, 1997).

Because several studies included multiple psychosocial predictors of the CAR, analyses were conducted by including all the effect sizes. To address concerns regarding the non-independence of effects drawn from the same sample, the same analyses were conducted again by selecting a single effect size at random from each study, and also by combining all the effect sizes from any study into a single average. Results did not differ with these approaches; thus, reported results include all effect sizes.

Analyses for predictor-specific effects

Chida and Steptoe (2009) described seven categories of psychosocial predictors that have been associated with the CAR: job stress, general life stress, depression, anxiety, fatigue/burnout/exhaustion, posttraumatic stress, and positive psychosocial traits. Because there were not enough significant p-values to compute independent p-curves by directionality and predictor type, p-values for both directions were entered simultaneously for each predictor. Thus, these p-curves tested whether there was evidential value for each predictor being associated with the CAR. Meta-analysis described the nature and directionality of the relationships.

Results

Study Characteristics and Quality

Table 1 reveals that studies were, on average, of medium to high quality, although quality scores varied considerably. The average number of sampling days was just over two days. The most frequently assessed psychosocial predictors were those assessing general life stress, depression, positive psychosocial traits, and anxiety/neuroticism/negative affect. Details for each of the studies are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Effect Size and Study Details of all Findings included in the Meta-Analysis.

| No | Author | Year | OutcomeTYPE* | N | r | Measure± |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | Adam | 2006 | DepressionDE | 52 | .01 | AINC |

| 1b | Adam | 2006 | Trait angerAX | 52 | .21 | AINC |

| 1c | Adam | 2006 | Trait anxietyAX | 52 | -.10 | AINC |

| Figfig | Adam et al | 2006 | FatigueFA | 156 | -.06 | AINC |

| 2b | Adam et al | 2006 | LonelinessGL | 156 | .14 | AINC |

| 2c | Adam et al | 2006 | Loss of controlGL | 156 | .17 | AINC |

| 2d | Adam et al | 2006 | Low liveliness/energyDE | 156 | .00 | AINC |

| 2e | Adam et al | 2006 | SadnessDE | 156 | .13 | AINC |

| 2f | Adam et al | 2006 | Tense/angryGL | 156 | .01 | AINC |

| 2g | Adam et al | 2006 | ThreatGL | 156 | .19 | AINC |

| 3a | Alderling et al | 2006 | Job stress (females)JS | 169 | .00 | AINC |

| 3b | Alderling et al | 2006 | Job stress (males)JS | 87 | .00 | AINC |

| 4 | Aubry et al | 2010 | Remitted depressionDE | 90 | .27 | AINC |

| 5a | Baes et al | 2014 | Childhood trauma and depressionDE | 23 | -.14 | AUCg |

| 5b | Baes et al | 2014 | DepressionDE | 30 | -.19 | AUCg |

| 6a | Barnett et al | 2005 | Poor marital qualityGL | 75 | .24 | AINC |

| 6b | Barnett et al | 2005 | Poor marital qualityGL | 75 | .23 | AUCg |

| 7 | Bhagwagar et al | 2003 | Past depressionDE | 62 | .32 | AUCg |

| 8 | Bhagwagar et al | 2005 | DepressionDE | 60 | .28 | AUCg |

| 9a | Bogg et al | 2015 | ConscientiousnessPO | 960 | -.02 | AINC |

| 9b | Bogg et al | 2015 | NeuroticismAX | 960 | .00 | AINC |

| 10a | Bosch et al | 2009 | Cognitive-affective symptoms (females)DE | 795 | .00 | AUCi |

| 10b | Bosch et al | 2009 | Cognitive-affective symptoms (males)DE | 785 | -.08 | AUCi |

| 10c | Bosch et al | 2009 | Somatic symptoms (females)DE | 795 | -.03 | AUCi |

| 10d | Bosch et al | 2009 | Somatic symptoms (males)DE | 785 | .09 | AUCi |

| 10e | Bosch et al | 2009 | Depressive symptomsDE | 1580 | -.01 | AUCi |

| 11 | Bouma et al | 2009 | Depressed moodDE | 568 | -.05 | AINC |

| 12a | Camfield et al | 2013 | Perceived stressGL | 138 | -.14 | AUCi |

| 12b | Camfield et al | 2013 | High stress (vs low stress)GL | 94 | .22 | AUCi |

| 13 | Chan et al | 2007 | NeuroticismAX | 65 | -.09 | AUCg |

| 14 | Chui et al | 2014 | Cumulative depressive symptomsDE | 50 | -.18 | AINC |

| 15 | Clingerman et al | 2013 | Work stressJS | 28 | .42 | AINC |

| 16 | Cropley et al | 2015 | Work-related ruminationJS | 108 | -.19 | AINC |

| 17a | Daubenmier et al | 2014 | AnxietyAX | 43 | .35 | AINC |

| 17b | Daubenmier et al | 2014 | Negative affectAX | 43 | .35 | AINC |

| 17c | Daubenmier et al | 2014 | Perceived stressGL | 43 | .44 | AINC |

| 17d | Daubenmier et al | 2014 | RuminationAX | 43 | .42 | AINC |

| 18a | Dedovic et al | 2010 | High-risk subclinical depressionDE | 36 | -.43 | AUCi |

| 18b | Dedovic et al | 2010 | Subclinical depressionDE | 50 | -.30 | AUCi |

| 19a | De Kloet et al | 2007 | PTSD symptomsPT | 47 | -.37 | AUCi |

| 19b | De Kloet et al | 2007 | PTSD symptomsPT | 47 | -.49 | AUCg |

| 20 | De Vente et al | 2003 | BurnoutFA | 45 | -.34 | ACOR |

| 21 | De Vugt et al | 2005 | Caregiver stressGL | 98 | -.21 | AINC |

| 22a | Diaz et al | 2013 | Competition stress (day 1)GL | 11 | .06 | AUCi |

| 22b | Diaz et al | 2013 | Competition stress (day 1)GL | 11 | .10 | AUCg |

| 22c | Diaz et al | 2013 | Negative mood (day 1)AX | 11 | -.55 | AUCi |

| 22d | Diaz et al | 2013 | Negative mood (day 1)AX | 11 | -.59 | AUCg |

| 22e | Diaz et al | 2013 | Competition stress (day 2)GL | 9 | .24 | AUCi |

| 22f | Diaz et al | 2013 | Competition stress (day 2)GL | 9 | .34 | AUCg |

| 22g | Diaz et al | 2013 | Negative mood (day 2)AX | 11 | -.70 | AUCi |

| 22h | Diaz et al | 2013 | Negative mood (day 2)AX | 11 | -.90 | AUCg |

| 23a | Dienes et al | 2013 | At-risk for depression (vs. control)DE | 42 | -.06 | AINC |

| 23b | Dienes et al | 2013 | Depressed status (vs. control)DE | 37 | .17 | AINC |

| 24a | Dietrich et al | 2013 | Aggression (mean scales)GL | 361 | .07 | AUCi |

| 24b | Dietrich et al | 2013 | Aggression (mean scales)GL | 361 | .00 | AUCg |

| 24c | Dietrich et al | 2013 | AggressionGL | 357 | .03 | AUCi |

| 24d | Dietrich et al | 2013 | AggressionGL | 1580 | .01 | AUCg |

| 24e | Dietrich et al | 2013 | Proactive aggressionGL | 361 | .00 | AUCi |

| 24f | Dietrich et al | 2013 | Reactive aggressionGL | 361 | .09 | AUCi |

| 24g | Dietrich et al | 2013 | Delinquent behaviorGL | 235 | .00 | AUCi |

| 24h | Dietrich et al | 2013 | Delinquent behaviorGL | 1578 | -.04 | AUCg |

| 24i | Dietrich et al | 2013 | AnxietyAX | 364 | .01 | AUCi |

| 24j | Dietrich et al | 2013 | AnxietyAX | 364 | .02 | AUCg |

| 24k | Dietrich et al | 2013 | DepressionDE | 361 | .07 | AUCg |

| 24l | Dietrich et al | 2013 | DepressionDE | 361 | .12 | AUCi |

| 24m | Dietrich et al | 2013 | Anxious/depressedDE | 789 | -.02 | AUCi |

| 24n | Dietrich et al | 2013 | Anxious/depressedDE | 1582 | .04 | AUCg |

| 25a | Doane et al | 2010 | Interpersonal stressGL | 108 | -.04 | AINC |

| 25b | Doane et al | 2010 | Trait lonelinessGL | 108 | -.08 | AINC |

| 26a | Doane et al | 2011 | DepressionDE | 735 | -.01 | AINC |

| 26b | Doane et al | 2011 | Negative emotionalityAX | 735 | .01 | AINC |

| 27 | Doane et al | 2015 | Childhood traumaPT | 82 | .13 | AUCi |

| 28a | Donoho et al | 2011 | Cumulative stressGL | 23 | .00 | AINC |

| 28b | Donoho et al | 2011 | Family stressGL | 23 | -.03 | AINC |

| 28c | Donoho et al | 2011 | Peer stressGL | 23 | .00 | AINC |

| 28d | Donoho et al | 2011 | Personal stressGL | 23 | -.04 | AINC |

| 28e | Donoho et al | 2011 | School stressGL | 23 | .13 | AINC |

| 29a | Drake et al | 2015 | Concurrent coping efficacyPO | 70 | .04 | AINC |

| 29b | Drake et al | 2015 | Concurrent lonelinessGL | 70 | -.09 | AINC |

| 29c | Drake et al | 2015 | Past coping efficacyPO | 70 | .19 | AINC |

| 29d | Drake et al | 2015 | Past lonelinessGL | 70 | -.07 | AINC |

| 30a | Duan et al | 2013 | AnxietyAX | 63 | -.30 | AINC |

| 30b | Duan et al | 2013 | AnxietyAX | 63 | .04 | AUCg |

| 30c | Duan et al | 2013 | Perceived stressGL | 63 | -.30 | AINC |

| 30d | Duan et al | 2013 | Perceived stressGL | 63 | -.05 | AUCg |

| 30e | Duan et al | 2013 | Test anxiety (vs. control)AX | 63 | -.35 | AINC |

| 30f | Duan et al | 2013 | Test anxiety (vs. control)AX | 63 | -.07 | AUCg |

| 31a | Ebrecht et al | 2004 | LonelinessGL | 24 | .00 | AUCg |

| 31b | Ebrecht et al | 2004 | OptimismPO | 24 | .00 | AUCg |

| 31c | Ebrecht et al | 2004 | Perceived stressGL | 24 | .00 | AUCg |

| 31d | Ebrecht et al | 2004 | Poor social supportGL | 24 | .00 | AUCg |

| 31e | Ebrecht et al | 2004 | Self-esteemPO | 24 | .00 | AUCg |

| 32a | Edwards et al | 2003 | Perceived stressGL | 26 | .37 | AUCg |

| 32b | Edwards et al | 2003 | Perceived stressGL | 26 | .00 | MINC |

| 33 | Eek et al | 2006 | Perceived stressGL | 381 | .00 | AINC |

| 34a | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | Daily hasslesGL | 57 | .02 | AINC |

| 34b | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | Daily hasslesGL | 57 | .14 | AUCg |

| 34c | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | DepressionDE | 57 | -.02 | AINC |

| 34d | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | DepressionDE | 57 | .09 | AUCg |

| 34e | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | InternalizingDE | 57 | .08 | AINC |

| 34f | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | InternalizingDE | 57 | .05 | AUCg |

| 34g | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | Major life eventsGL | 57 | -.09 | AINC |

| 34h | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | Major life eventsGL | 57 | -.11 | AUCg |

| 34i | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | Negative affectAX | 57 | .07 | AINC |

| 34j | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | Negative affectAX | 57 | .10 | AUCg |

| 34k | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | Positive affectPO | 57 | .05 | AINC |

| 34l | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | Positive affectPO | 57 | .17 | AUCg |

| 34m | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | Social problemsGL | 57 | .16 | AINC |

| 34n | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | Social problemsGL | 57 | .07 | AUCg |

| 34o | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | State anxietyAX | 57 | .02 | AINC |

| 34p | Ellenbogen et al | 2006 | State anxietyAX | 57 | -.07 | AUCg |

| 35a | Ellenbogen et al | 2009 | Parental functioningPO | 43 | -.13 | AUCi |

| 35b | Ellenbogen et al | 2009 | Parental controlPO | 43 | -.22 | AUCi |

| 35c | Ellenbogen et al | 2009 | Parental neuroticismAX | 43 | .03 | AUCi |

| 35d | Ellenbogen et al | 2009 | Parental structurePO | 43 | -.35 | AUCi |

| 35e | Ellenbogen et al | 2009 | Parental supportPO | 43 | -.07 | AUCi |

| 36a | Eller et al | 2006 | Job stress (low control), malesJS | 28 | .00 | AINC |

| 36b | Eller et al | 2006 | Job stress (high demand), malesJS | 28 | -.02 | AINC |

| 36c | Eller et al | 2006 | Job stress (ERI model), malesJS | 28 | .00 | AINC |

| 36d | Eller et al | 2006 | Job stress (over-commitment), malesJS | 28 | .03 | AINC |

| 36e | Eller et al | 2006 | Time pressure, malesJS | 28 | .00 | AINC |

| 36f | Eller et al | 2006 | Job stress (low control), femalesJS | 47 | .01 | AINC |

| 36g | Eller et al | 2006 | Job stress (high demand), femalesJS | 52 | .00 | AINC |

| 36h | Eller et al | 2006 | Job stress (ERI model), femalesJS | 53 | .15 | AINC |

| 36i | Eller et al | 2006 | Job stress (over-commitment), femalesJS | 50 | .00 | AINC |

| 36j | Eller et al | 2006 | Time pressure, femalesJS | 55 | .31 | AINC |

| 37a | Eller et al | 2011 | Job controlPO | 70 | .05 | AINC |

| 37b | Eller et al | 2011 | Job demandsJS | 70 | .04 | AINC |

| 37c | Eller et al | 2011 | Job effortJS | 70 | .06 | AINC |

| 37d | Eller et al | 2011 | Job effort-reward imbalanceJS | 70 | -.04 | AINC |

| 37e | Eller et al | 2011 | Job rewardPO | 70 | -.04 | AINC |

| 37f | Eller et al | 2011 | Job strainJS | 70 | .01 | AINC |

| 37g | Eller et al | 2011 | Life events (past year)GL | 70 | -.02 | AINC |

| 38a | Endrighi et al | 2011 | DepressionDE | 422 | .01 | AINC |

| 38 | Endrighi et al | 2011 | OptimismPO | 422 | -.11 | AINC |

| 39a | Engert et al | 2011 | Anxiety symptomsAX | 58 | .28 | AINC |

| 39b | Engert et al | 2011 | Depressive symptomsDE | 58 | .33 | AINC |

| 39c | Engert et al | 2011 | Low early-life parental careGL | 58 | .34 | AINC |

| 39d | Engert et al | 2011 | Self-esteemPO | 58 | -.24 | AINC |

| 40a | Fairchild et al | 2008 | Adolescent-onset CD (vs. control)GL | 116 | -.27 | AUCi |

| 40b | Fairchild et al | 2008 | Early-Onset CD (vs. control)GL | 134 | -.33 | AUCi |

| 41a | Fekedulegn et al | 2012 | Percent of hours on midnight shiftJS | 65 | -.32 | AUCg |

| 41b | Fekedulegn et al | 2012 | Percent of hours on midnight shiftJS | 65 | -.04 | AUCi |

| 42 | Franz et al | 2013 | Childhood disadvantageGL | 727 | .06 | AINC |

| 43a | Freitag et al | 2009 | ADHD (vs. control)GL | 121 | .20 | MINC |

| 43b | Freitag et al | 2009 | ADHD + CD (vs. control)GL | 91 | .11 | MINC |

| 43c | Freitag et al | 2009 | ADHD + ODD (vs. control)GL | 118 | .20 | MINC |

| 43d | Freitag et al | 2009 | ADHD with anxiety (vs. control)GL | 106 | .17 | MINC |

| 43e | Freitag et al | 2009 | ADHD without anxiety (vs. control)GL | 155 | .20 | MINC |

| 44a | Garcia-Banda et al | 2014 | NeuroticismAX | 118 | .04 | AINC |

| 44b | Garcia-Banda et al | 2014 | NeuroticismAX | 118 | .02 | AUCg |

| 45a | Gartland et al | 2014 | Daily negative affectAX | 64 | .00 | AUCi |

| 45b | Gartland et al | 2014 | Daily positive affectPO | 64 | .00 | AUCi |

| 45c | Gartland et al | 2014 | Hassle appraisalGL | 64 | .00 | AUCi |

| 46a | Gonzalez-bono et al | 2011 | Caregiver burdenGL | 38 | .00 | AINC |

| 46b | Gonzalez-bono et al | 2011 | CaregivingGL | 70 | -.27 | AINC |

| 46c | Gonzalez-bono et al | 2011 | Psychopathology of care recipientGL | 38 | -.50 | AINC |

| 46d | Gonzalez-bono et al | 2011 | Schizophrenia symptoms of care recipientGL | 38 | -.35 | AINC |

| 47a | Gonzalez-Cabrera et al | 2014 | Perceived stressGL | 36 | .01 | AINC |

| 47b | Gonzalez-Cabrera et al | 2014 | State anxietyAX | 36 | .24 | AINC |

| 47c | Gonzalez-Cabrera et al | 2014 | Trait anxietyAX | 36 | .28 | AINC |

| 48a | Gostisha et al | 2014 | Callous-unemotional traitsGL | 50 | .28 | Slope |

| 48b | Gostisha et al | 2014 | Psychopathy symptomsGL | 50 | .37 | Slope |

| 48c | Gostisha et al | 2014 | Stress exposureGL | 50 | .35 | Slope |

| 49 | Grant et al | 2009 | Social isolationGL | 145 | .20 | AINC |

| 50a | Greaves-Lord et al | 2007 | Current anxietyAX | 376 | .00 | AUCg |

| 50b | Greaves-Lord et al | 2007 | Persistent anxietyGL | 354 | .13 | AUCg |

| 51a | Grossi et al | 2005 | Burnout, malesFA | 29 | .00 | MINC |

| 51b | Grossi et al | 2005 | Burnout, malesFA | 29 | .00 | AUCg |

| 51c | Grossi et al | 2005 | Burnout, femalesFA | 35 | .00 | MINC |

| 51d | Grossi et al | 2005 | Burnout, femalesFA | 35 | .26 | AUCg |

| 52 | Gustafsson et al | 2010 | Acumulated life adversityGL | 130 | .31 | AINC |

| 53 | Gustafsson et al | 2012 | Cumulation of temporary employmentJS | 755 | .08 | AINC |

| 54 | Hansen et al | 2011 | BullyingGL | 1717 | -.03 | 30min |

| 55a | Harris et al | 2007 | Job stress (DC model)JS | 44 | .17 | AUCi |

| 55b | Harris et al | 2007 | Job stress (ERI model)JS | 39 | -.11 | AUCi |

| 55c | Harris et al | 2007 | Poor social supportGL | 42 | .27 | AUCi |

| 55d | Harris et al | 2007 | VitalityPO | 42 | -.32 | AUCi |

| 55e | Harris et al | 2007 | Well-beingPO | 42 | -.19 | AUCi |

| 56a | Hartman et al | 2013 | Externalizing (checklist)GL | 211 | .03 | AUCi |

| 56b | Hartman et al | 2013 | Externalizing (checklist)GL | 211 | .00 | AUCg |

| 56c | Hartman et al | 2013 | Externalizing (self-report)GL | 211 | .01 | AUCi |

| 56d | Hartman et al | 2013 | Externalizing (self-report)GL | 211 | -.09 | AUCg |

| 56e | Hartman et al | 2013 | Internalizing (checklist)DE | 211 | -.03 | AUCi |

| 56f | Hartman et al | 2013 | Internalizing (checklist)DE | 211 | .03 | AUCg |

| 56g | Hartman et al | 2013 | Internalizing (self-report)DE | 211 | .10 | AUCi |

| 56h | Hartman et al | 2013 | Internalizing (self-report)DE | 211 | .13 | AUCg |

| 56i | Hartman et al | 2013 | Internalizing × Externalizing (checklist)DE | 211 | .02 | AUCi |

| 56j | Hartman et al | 2013 | Internalizing × Externalizing (checklist)DE | 211 | .07 | AUCg |

| 56k | Hartman et al | 2013 | Internalizing × Externalizing (self-report)DE | 211 | .03 | AUCi |

| 56l | Hartman et al | 2013 | Internalizing × Externalizing (self-report)DE | 211 | .17 | AUCg |

| 57a | Hartwig et al | 2013 | Alexithymia (high vs. low)GL | 78 | -.34 | AUCi |

| 57b | Hartwig et al | 2013 | AlexithymiaGL | 78 | -.29 | AUCi |

| 58a | Heaney et al | 2010 | AnxietyAX | 24 | .46 | AINC |

| 58b | Heaney et al | 2010 | DepressionDE | 24 | .59 | AINC |

| 59 | Heim et al | 2009 | FatigueFA | 237 | -.17 | AUCg |

| 60a | Hek et al | 2013 | Anxiety disorder (vs. control)AX | 1788 | -.05 | AINC |

| 60b | Hek et al | 2013 | Anxiety disorder (vs. control)AX | 1788 | -.04 | AUCg |

| 61a | Hibel et al | 2014 | Job strainJS | 56 | .05 | AINC |

| 61b | Hibel et al | 2014 | Parenting stressGL | 56 | .06 | AINC |

| 62a | Hicks et al | 2011 | Attachment anxietyAX | 39 | .14 | AINC |

| 62b | Hicks et al | 2011 | Attachment avoidanceGL | 39 | -.15 | AINC |

| 62c | Hicks et al | 2011 | Daily conflictGL | 39 | -.37 | AINC |

| 62d | Hicks et al | 2011 | Morning negative affectAX | 39 | -.06 | AINC |

| 62e | Hicks et al | 2011 | Night negative affectGL | 39 | .21 | AINC |

| 63a | Hill et al | 2013 | AgreeablenessPO | 92 | -.08 | AUCi |

| 63b | Hill et al | 2013 | AgreeablenessPO | 92 | -.03 | AUCg |

| 63c | Hill et al | 2013 | ConscientiousnessPO | 92 | -.16 | AUCi |

| 63d | Hill et al | 2013 | ConscientiousnessPO | 92 | .03 | AUCg |

| 63e | Hill et al | 2013 | ExtraversionPO | 92 | .13 | AUCi |

| 63f | Hill et al | 2013 | ExtraversionPO | 92 | .24 | AUCg |

| 63g | Hill et al | 2013 | NeuroticismAX | 92 | -.03 | AUCi |

| 63h | Hill et al | 2013 | NeuroticismAX | 92 | -.11 | AUCg |

| 63i | Hill et al | 2013 | OpennessPO | 92 | .08 | AUCi |

| 63j | Hill et al | 2013 | OpennessPO | 92 | .06 | AUCg |

| 64a | Holleman et al | 2012 | Decision latitudeJS | 1048 | -.05 | AUCi |

| 64b | Holleman et al | 2012 | Decision lattitudeJS | 1048 | -.05 | AUCg |

| 64c | Holleman et al | 2012 | Job demandsJS | 1048 | -.03 | AUCi |

| 64d | Holleman et al | 2012 | Job demandsJS | 1048 | .02 | AUCg |

| 64e | Holleman et al | 2012 | Job insecurityJS | 1048 | .03 | AUCi |

| 64f | Holleman et al | 2012 | Job insecurityJS | 1048 | .00 | AUCg |

| 64g | Holleman et al | 2012 | Job strainJS | 1048 | -.01 | AUCi |

| 64h | Holleman et al | 2012 | Job strainJS | 1048 | .01 | AUCg |

| 64i | Holleman et al | 2012 | Negative life eventsGL | 1680 | -.02 | AUCi |

| 64j | Holleman et al | 2012 | Negative life eventsGL | 1680 | .02 | AUCg |

| 64k | Holleman et al | 2012 | Social supportPO | 1048 | .01 | AUCi |

| 64l | Holleman et al | 2012 | Social supportPO | 1048 | .03 | AUCg |

| 64m | Holleman et al | 2012 | Physical abusePT | 1680 | -.02 | AUCi |

| 64n | Holleman et al | 2012 | Physical abusePT | 1680 | -.01 | AUCg |

| 64o | Holleman et al | 2012 | Emotional abusePT | 1680 | .01 | AUCi |

| 64p | Holleman et al | 2012 | Emotional abusePT | 1680 | .04 | AUCg |

| 64q | Holleman et al | 2012 | Sexual abusePT | 1680 | -.01 | AUCi |

| 64r | Holleman et al | 2012 | Sexual abusePT | 1680 | .00 | AUCg |

| 64s | Holleman et al | 2012 | Trauma indexPT | 1680 | .00 | AUCi |

| 64t | Holleman et al | 2012 | Trauma indexPT | 1680 | .02 | AUCg |

| 65a | Hoyt et al | 2015 | High-arousal negative affectPO | 315 | .00 | ACOR |

| 65b | Hoyt et al | 2015 | High-arousal positive affectPO | 315 | -.05 | ACOR |

| 65c | Hoyt et al | 2015 | Low-arousal negative affectPO | 315 | .01 | ACOR |

| 65d | Hoyt et al | 2015 | Low-arousal positive affectPO | 315 | .04 | ACOR |

| 66a | Imeraj et al | 2012 | ADHD + ODD (vs. controls)GL | 66 | .05 | AINC |

| 66b | Imeraj et al | 2012 | ADHD only (vs. controls)GL | 66 | -.16 | AINC |

| 67 | Isaksson et al | 2013 | ADHDGL | 308 | -.04 | AINC |

| 68a | Isaksson et al | 2015 | ADHDGL | 185 | -.16 | AINC |

| 68b | Isaksson et al | 2015 | Perceived stressGL | 185 | .00 | AINC |

| 69a | Izawa et al | 2007 | Writing graduation thesisGL | 12 | .00 | AUCi |

| 69b | Izawa et al | 2007 | Writing graduation thesisGL | 12 | .50 | AUCg |

| 70a | Jabben et al | 2011 | Bipolar depressionDE | 1571 | -.75 | AUCi |

| 70b | Jabben et al | 2011 | Bipolar depressionDE | 1571 | .14 | AUCg |

| 70c | Jabben et al | 2011 | Unipolar depressionDE | 1571 | -.68 | AUCi |

| 70d | Jabben et al | 2011 | Unipolar depressionDE | 1571 | .09 | AUCg |

| 71 | Jarcho et al | 2013 | DepressionDE | 49 | -.04 | AINC |

| 72 | Jobin et al | 2014 | Perceived stress and pessimismGL | 135 | .22 | AINC |

| 73a | Johnson et al | 2008 | Abuse chronicityPT | 52 | -.21 | AUCi |

| 73b | Johnson et al | 2008 | Abuse chronicityPT | 52 | -.26 | AUCg |

| 73c | Johnson et al | 2008 | DepressionDE | 52 | .28 | AUCi |

| 73d | Johnson et al | 2008 | DepressionDE | 52 | .08 | AUCg |

| 73e | Johnson et al | 2008 | Posttraumatic stress disorder symptomsPT | 52 | .34 | AUCi |

| 73f | Johnson et al | 2008 | Posttraumatic stress disorder symptomsPT | 52 | .31 | AUCg |

| 74a | Johnson et al | 2014 | Affective empathyPO | 57 | .26 | AINC |

| 74b | Johnson et al | 2014 | Blame externalizationGL | 57 | -.26 | AINC |

| 74c | Johnson et al | 2014 | Carefree nonplanfulnessGL | 57 | -.24 | AINC |

| 74d | Johnson et al | 2014 | Cognitive empathyPO | 57 | .05 | AINC |

| 74e | Johnson et al | 2014 | ColdheartednessGL | 57 | .00 | AINC |

| 74f | Johnson et al | 2014 | FearlessnessGL | 57 | .00 | AINC |

| 74g | Johnson et al | 2014 | Impulsive nonconformityGL | 57 | .00 | AINC |

| 74h | Johnson et al | 2014 | Machavellian egocentricityGL | 57 | -.26 | AINC |

| 74i | Johnson et al | 2014 | Proactive physical aggressionGL | 57 | .00 | AINC |

| 74j | Johnson et al | 2014 | Proactive relational aggressionGL | 57 | .00 | AINC |

| 74k | Johnson et al | 2014 | Prosocial behaviorPO | 57 | .26 | AINC |

| 74l | Johnson et al | 2014 | Psychopathy (total score)GL | 57 | .00 | AINC |

| 74m | Johnson et al | 2014 | Reactive physical aggressionGL | 57 | -.26 | AINC |

| 74n | Johnson et al | 2014 | Reactive relational aggressionGL | 57 | .00 | AINC |

| 74o | Johnson et al | 2014 | Social potencyPO | 57 | .34 | AINC |

| 74p | Johnson et al | 2014 | Stress immunityPO | 57 | .00 | AINC |

| 75a | Kallen et al | 2008 | Anxiety, femalesAX | 46 | .29 | AINC |

| 75b | Kallen et al | 2008 | Anxiety, malesAX | 53 | .00 | AINC |

| 76a | Kaplow et al | 2013 | Anxiety after parental lossAX | 38 | -.29 | AINC |

| 76b | Kaplow et al | 2013 | Avoidant coping after parental lossGL | 38 | -.37 | MINC |

| 76c | Kaplow et al | 2013 | Depression after parental lossDE | 38 | -.24 | AUCi |

| 76d | Kaplow et al | 2013 | Maladaptive grief after parental lossDE | 38 | -.16 | AINC |

| 76e | Kaplow et al | 2013 | Parental maladaptive griefDE | 38 | -.21 | AUCi |

| 76f | Kaplow et al | 2013 | PTSD after parental lossPT | 38 | -.26 | AINC |

| 77 | Karhula et al | 2015 | Job strainJS | 95 | -.20 | AINC |

| 78a | Keeshin et al | 2014 | PTSD symptomsPT | 24 | -.41 | AINC |

| 78b | Keeshin et al | 2014 | Sexual abusePT | 36 | .03 | AINC |

| 79a | Kim et al | 2015 | Physical victimization, malesPT | 122 | .06 | ACOR |

| 79b | Kim et al | 2015 | Physical victimization, femalesPT | 122 | -.04 | ACOR |

| 79c | Kim et al | 2015 | Psychological victimization, malesPT | 122 | .01 | ACOR |

| 79d | Kim et al | 2015 | Psychological victimization, femalesPT | 122 | .01 | ACOR |

| 79e | Kim et al | 2015 | Relationship satisfaction, malesPO | 122 | .00 | ACOR |

| 79f | Kim et al | 2015 | Relationship satisfaction, femalesPO | 122 | .00 | ACOR |

| 80 | Klaassens et al | 2009 | TraumaPT | 20 | -.02 | AUCg |

| 81a | Klaassens et al | 2010 | Work traumaPT | 882 | -.01 | AUCi |

| 81b | Klaassens et al | 2010 | Work traumaPT | 62 | -.26 | AUCg |

| 82a | Klein et al | 2012 | Cognitive intrusionsAX | 38 | -.06 | AUCg |

| 82b | Klein et al | 2012 | Job-stressJS | 38 | .35 | AUCg |

| 82c | Klein et al | 2012 | Mental distance from workJS | 38 | -.08 | AUCg |

| 83a | Klein et al | 2014 | Care-related stressorsGL | 158 | -.03 | Slope |

| 83b | Klein et al | 2014 | Duration of careGL | 158 | -.01 | Slope |

| 83c | Klein et al | 2014 | Noncare-related stressorsGL | 158 | .02 | Slope |

| 83d | Klein et al | 2014 | Positive eventsPO | 158 | .05 | Slope |

| 84a | Kliewer et al | 2006 | InternalizingDE | 78 | .00 | ACOR |

| 84b | Kliewer et al | 2006 | Major life eventsGL | 78 | .05 | ACOR |

| 84c | Kliewer et al | 2006 | Peer victimizationGL | 78 | -.10 | ACOR |

| 84d | Kliewer et al | 2006 | Witnessed violence, malesPT | 45 | .00 | ACOR |

| 84e | Kliewer et al | 2006 | Witnessed violence, femalesPT | 33 | -.09 | ACOR |

| 85 | Knack et al | 2011 | Peer victimizationGL | 107 | -.20 | Slope |

| 86 | Kuehl et al | 2015 | Major depressive disorderDE | 85 | -.08 | AUCg |

| 87 | Kuehner et al | 2011 | NeuroticismAX | 66 | -.12 | AUCi |

| 88a | Kuhlman et al | 2015 | Current depressionDE | 121 | .04 | AINC |

| 88b | Kuhlman et al | 2015 | Emotional abusePT | 121 | .17 | AINC |

| 88c | Kuhlman et al | 2015 | Non-intentional traumaPT | 121 | .16 | AINC |

| 88d | Kuhlman et al | 2015 | Physical abusePT | 121 | .10 | AINC |

| 89 | Kumari et al | 2009 | FatigueFA | 4364 | -.01 | AINC |

| 90 | Kumari et al | 2013 | Maternal separationGL | 3712 | .04 | AINC |

| 91a | Lac et al | 2012 | Anxiety and depressionDE | 69 | .17 | AUCi |

| 91b | Lac et al | 2012 | AnxietyAX | 69 | .23 | AUCi |

| 91c | Lac et al | 2012 | Bullied at workGL | 69 | -.11 | AUCi |

| 91d | Lac et al | 2012 | DepressionDE | 69 | .06 | AUCi |

| 91e | Lac et al | 2012 | StressGL | 69 | .08 | AUCi |

| 92a | Laceulle et al | 2014 | AssertivenessPO | 343 | .01 | AINC |

| 92b | Laceulle et al | 2014 | Excitement seekingGL | 343 | -.03 | AINC |

| 92c | Laceulle et al | 2014 | HostilityGL | 343 | .03 | AINC |

| 92d | Laceulle et al | 2014 | ImpulsivenessGL | 343 | -.01 | AINC |

| 92e | Laceulle et al | 2014 | Self-disciplineGL | 343 | -.11 | AINC |

| 92f | Laceulle et al | 2014 | VulnerabilityGL | 343 | .02 | AINC |

| 93a | Lai et al | 2005 | Negative affectAX | 80 | .00 | AUCg |

| 93b | Lai et al | 2005 | OptimismPO | 80 | -.31 | AUCg |

| 93c | Lai et al | 2005 | Positive affectPO | 80 | .00 | AUCg |

| 94a | Lai et al | 2010 | HumorPO | 45 | -.02 | AUCi |

| 94b | Lai et al | 2010 | HumorPO | 45 | -.32 | AUCg |

| 94c | Lai et al | 2010 | Self-esteemPO | 45 | .20 | AUCi |

| 94d | Lai et al | 2010 | Self-esteemPO | 45 | .06 | AUCg |

| 95a | Lai et al | 2012 | Social network cultivationPO | 78 | .22 | ACOR |

| 95b | Lai et al | 2012 | Social network emotional supportPO | 78 | .02 | ACOR |

| 95c | Lai et al | 2012 | Social network sizePO | 78 | .02 | ACOR |

| 96a | Lamers et al | 2013 | Atypical depressionDE | 665 | .08 | AUCi |

| 96b | Lamers et al | 2013 | Atypical depressionDE | 665 | -.09 | AUCg |

| 96c | Lamers et al | 2013 | Melancholic depressionDE | 654 | .09 | AUCi |

| 96d | Lamers et al | 2013 | Melancholic depressionDE | 654 | .16 | AUCg |

| 97a | Langelaan et al | 2006 | BurnoutFA | 45 | .00 | AUCi |

| 97b | Langelaan et al | 2006 | Work engagementPO | 51 | .00 | AUCi |

| 98a | Laudenslager et al | 2009 | PTSD symptomsPT | 42 | -.12 | AINC |

| 98b | Laudenslager et al | 2009 | PTSD symptomsPT | 17 | .07 | AINC |

| 99a | Lederbogen et al | 2010 | Depressive symptomsDE | 718 | .04 | AINC |

| 99b | Lederbogen et al | 2010 | Social supportGL | 718 | -.04 | AINC |

| 99c | Lederbogen et al | 2010 | Subjective health (mental symptoms)GL | 718 | .05 | AINC |

| 99d | Lederbogen et al | 2010 | Subjective health (physical symptoms)GL | 718 | .02 | AINC |

| 100a | Leggett et al | 2014 | AngerGL | 164 | .00 | Slope |

| 100b | Leggett et al | 2014 | Depressive moodDE | 164 | -.20 | Slope |

| 101 | Liao et al | 2012 | Job strainJS | 1988 | .01 | AINC |

| 102a | Lindholm et al | 2012 | Severe stressPT | 131 | .19 | T1/T0 |

| 102b | Lindholm et al | 2012 | Shift workJS | 131 | .45 | T1/T0 |

| 103 | Lovell et al | 2011 | Perceived stressGL | 32 | -.16 | AINC |

| 104a | Lovell et al | 2012 | Social support appraisalPO | 45 | .17 | AINC |

| 104b | Lovell et al | 2012 | Social support belongingPO | 45 | .20 | AINC |

| 104c | Lovell et al | 2012 | Social support self-esteemPO | 45 | .35 | AINC |

| 104d | Lovell et al | 2012 | Social support tangiblePO | 45 | .11 | AINC |

| 105a | Lovell et al | 2015 | AnxietyAX | 18 | -.13 | AINC |

| 105b | Lovell et al | 2015 | Caregiving for child with autism or ADHDGL | 57 | -.03 | AINC |

| 105c | Lovell et al | 2015 | DepressionDE | 18 | -.07 | AINC |

| 105d | Lovell et al | 2015 | Perceived stressGL | 18 | -.40 | AINC |

| 106a | Lu et al | 2013 | Childhood traumaPT | 48 | .34 | AINC |

| 106b | Lu et al | 2013 | Childhood traumaPT | 48 | .32 | AUCg |

| 107 | Madsen et al | 2012 | NeuroticismAX | 48 | .31 | AINC |

| 108a | Maina et al | 2009 | Job strain (group 1)JS | 68 | .00 | AUCg |

| 108b | Maina et al | 2009 | Job strain (group 2)JS | 36 | .32 | AUCg |

| 108c | Maina et al | 2009 | Job effort (group 1)JS | 68 | .00 | AUCg |

| 108d | Maina et al | 2009 | Job effort (group 2)JS | 36 | -.32 | AUCg |

| 108e | Maina et al | 2009 | Job reward (group 1)PO | 68 | .23 | AUCg |

| 108f | Maina et al | 2009 | Job reward (group 2)PO | 36 | .00 | AUCg |

| 108g | Maina et al | 2009 | Job effort-reward imbalance (group 1)JS | 68 | -.23 | AUCg |

| 108h | Maina et al | 2009 | Job effort-reward imbalance (group 2)JS | 36 | .00 | AUCg |

| 109a | Maina, Palmas et al | 2009 | Decision latitude at workPO | 36 | .00 | AUCi |

| 109b | Maina, Palmas et al | 2009 | Decision latitude at workPO | 36 | .00 | AUCg |

| 109c | Maina, Palmas et al | 2009 | Psychological demands at workJS | 36 | .00 | AUCi |

| 109d | Maina, Palmas et al | 2009 | Psychological demands at workJS | 36 | .00 | AUCg |

| 110a | Mangold et al | 2010 | High trauma exposure (vs moderate)GL | 59 | -.13 | AINC |

| 110b | Mangold et al | 2010 | Moderate/high trauma exposure (vs. low)GL | 59 | -.42 | AINC |

| 111a | Mangold et al | 2011 | Depressive symptomatologyDE | 55 | -.32 | AINC |

| 111b | Mangold et al | 2011 | Emotional abusePT | 55 | -.28 | AINC |

| 111c | Mangold et al | 2011 | General traumasPT | 55 | -.34 | AINC |

| 111d | Mangold et al | 2011 | Physical abusePT | 55 | -.25 | AINC |

| 111e | Mangold et al | 2011 | Sexual abusePT | 55 | -.23 | AINC |

| 112 | Mangold et al | 2012 | High acculturation and neuroticismAX | 30 | -.52 | ACOR |

| 113 | Marchand et al | 2014 | BurnoutFA | 401 | -.13 | AINC |

| 114a | Marsman et al | 2012 | Perceived parental rejectionGL | 1594 | -.03 | AUCi |

| 114b | Marsman et al | 2012 | Perceived parental rejectionGL | 1594 | -.04 | AUCg |

| 114c | Marsman et al | 2012 | Perceived parental warmthPO | 1594 | -.03 | AUCi |

| 114d | Marsman et al | 2012 | Perceived parental warmthPO | 1594 | -.08 | AUCg |

| 115 | Meinlschmidt et al | 2005 | Early loss eventPT | 95 | -.29 | AINC |

| 116a | Mello et al | 2015 | Physical punishmentPT | 113 | -.24 | AUCg |

| 116b | Mello et al | 2015 | Working on the streetsJS | 113 | .22 | AUCg |

| 117a | Merwin et al | 2015 | Parental hostilityGL | 149 | -.26 | AUCi |

| 117b | Merwin et al | 2015 | Parental hostilityGL | 149 | -.13 | AUCg |

| 118a | Mikolajczak et al | 2010 | HappinessPO | 41 | -.38 | Slope |

| 118b | Mikolajczak et al | 2010 | NeuroticismAX | 41 | .53 | Slope |

| 118c | Mikolajczak et al | 2010 | Perceived stressGL | 41 | -.55 | Slope |

| 119a | Mommersteeg et al | 2006 | DepressionDE | 34 | .04 | AUCi |

| 119b | Mommersteeg et al | 2006 | DepressionDE | 34 | -.10 | AUCg |

| 119c | Mommersteeg et al | 2006 | Depression + burnoutDE | 73 | .10 | AUCi |

| 119d | Mommersteeg et al | 2006 | Depression + burnout DE | 73 | .10 | AUCg |

| 119e | Mommersteeg et al | 2006 | ExhaustionFA | 34 | -.14 | AUCi |

| 119f | Mommersteeg et al | 2006 | ExhaustionFA | 34 | -.09 | AUCg |

| 119g | Mommersteeg et al | 2006 | Exhaustion + burnoutFA | 73 | -.05 | AUCi |

| 119h | Mommersteeg et al | 2006 | Exhaustion + burnoutFA | 73 | -.02 | AUCg |

| 119i | Mommersteeg et al | 2006 | NeuroticismAX | 34 | .04 | AUCi |

| 119j | Mommersteeg et al | 2006 | NeuroticismAX | 34 | -.14 | AUCg |

| 119k | Mommersteeg et al | 2006 | Neuroticism + burnoutAX | 72 | -.12 | AUCi |

| 119l | Mommersteeg et al | 2006 | Neuroticism + burnoutAX | 72 | -.07 | AUCg |

| 120a | Mossink et al | 2015 | Current-day negative affectAX | 55 | -.03 | AINC |

| 120b | Mossink et al | 2015 | Current-day negative memory biasAX | 55 | -.23 | AINC |

| 120c | Mossink et al | 2015 | Current-day positive affectPO | 55 | .07 | AINC |

| 120d | Mossink et al | 2015 | Prior-day negative affectAX | 55 | .21 | AINC |

| 120e | Mossink et al | 2015 | Prior-day negative memory biasGL | 55 | .04 | AINC |

| 120f | Mossink et al | 2015 | Prior-day positive affectPO | 55 | -.16 | AINC |

| 120g | Mossink et al | 2015 | Prior-day sadnessDE | 55 | .29 | AINC |

| 121 | Moya-Albiol et al | 2010 | BurnoutFA | 64 | -.60 | AINC |

| 122 | Nagy et al | 2015 | NightmaresGL | 188 | -.19 | AUCg |

| 123a | Nelemans et al | 2014 | DepressionDE | 184 | .16 | AUCg |

| 123b | Nelemans et al | 2014 | Generalized anxiety disorderAX | 184 | .08 | AUCg |

| 123c | Nelemans et al | 2014 | Panic disorderAX | 184 | .13 | AUCg |

| 123d | Nelemans et al | 2014 | Separation anxiety disorderAX | 184 | .19 | AUCg |

| 123e | Nelemans et al | 2014 | Social anxiety disorderAX | 184 | .04 | AUCg |

| 124 | Neu et al | 2014 | Life stressGL | 52 | -.16 | AINC |

| 125 | Neylan et al | 2005 | PTSD symptomsPT | 30 | -.51 | AUCg |

| 126 | Nicolson et al | 2000 | ExhaustionFA | 59 | .11 | AINC |

| 127 | O'Donnell et al | 2008 | DepressionDE | 542 | -.03 | AINC |

| 128a | O'Connor et al | 2009 | Educational attainmentPO | 118 | .21 | AUCi |

| 128b | O'Connor et al | 2009 | Perceived stressGL | 118 | -.22 | AUCi |

| 129a | Okamura et al | 2011 | Loneliness, weekendsGL | 90 | .20 | AINC |

| 129b | Okamura et al | 2011 | Loneliness, workdaysGL | 90 | .00 | AINC |

| 130a | Olsson et al | 2010 | Burnout (fatigue group)FA | 36 | .14 | AUCg |

| 130b | Olsson et al | 2010 | Burnout (controls)FA | 16 | .07 | AUCg |

| 130c | Olsson et al | 2010 | Depressive symptoms (fatigue group)DE | 36 | .08 | AUCg |

| 130d | Olsson et al | 2010 | Depressive symptoms (controls)DE | 16 | -.10 | AUCg |

| 130e | Olsson et al | 2010 | Stress-related fatigueFA | 55 | .35 | AUCg |

| 131 | Ong et al | 2011 | Spousal lossGL | 44 | .09 | AINC |

| 132a | Oosterholt et al | 2015 | Clinical burnoutFA | 62 | -.12 | AINC |

| 132b | Oosterholt et al | 2015 | Clinical burnoutFA | 62 | -.30 | AUCg |

| 132c | Oosterholt et al | 2015 | Non-clinical burnoutFA | 59 | -.16 | AINC |

| 132d | Oosterholt et al | 2015 | Non-clinical burnoutFA | 59 | -.29 | AUCg |

| 133 | Oskis et al | 2011 | Anxious attachmentAX | 60 | -.39 | MINC |

| 134a | Oskis et al | 2015 | Active emotional support from motherPO | 55 | -.20 | AINC |

| 134b | Oskis et al | 2015 | AngerGL | 55 | -.05 | AINC |

| 134c | Oskis et al | 2015 | Confiding in motherPO | 55 | -.16 | AINC |

| 134d | Oskis et al | 2015 | Constraints on closenessPT | 55 | .08 | AINC |

| 134e | Oskis et al | 2015 | Fear of rejectionGL | 55 | -.37 | AINC |

| 134f | Oskis et al | 2015 | Fear of separationGL | 55 | -.26 | AINC |

| 134g | Oskis et al | 2015 | High desire for companyGL | 55 | -.20 | AINC |

| 134h | Oskis et al | 2015 | MistrustGL | 55 | .23 | AINC |

| 135 | Osterberg et al | 2009 | BurnoutFA | 221 | .02 | AINC |

| 136a | Peng et al | 2014 | Dysfunctional attitudesGL | 109 | .09 | AINC |

| 136b | Peng et al | 2014 | DepressionDE | 109 | -.10 | AINC |

| 136c | Peng et al | 2014 | Childhood neglect (vs control)PT | 51 | .18 | AINC |

| 136d | Peng et al | 2014 | Childhood neglect (continuous)PT | 109 | .26 | AINC |

| 136e | Peng et al | 2014 | Depression + child neglect (vs. control)DE | 57 | .35 | AUCi |

| 136f | Peng et al | 2014 | Depression w/o child neglect (vs. control)DE | 59 | -.34 | AINC |

| 137a | Pinna et al | 2014 | Chronicity of abusePT | 104 | .09 | AUCi |

| 137b | Pinna et al | 2014 | Chronicity of abusePT | 104 | -.26 | AUCg |

| 137c | Pinna et al | 2014 | Comorbid PTSD and depressionDE | 67 | .02 | AUCi |

| 137d | Pinna et al | 2014 | Comorbid PTSD and depressionDE | 67 | .32 | AUCg |

| 137e | Pinna et al | 2014 | DepressionDE | 104 | .65 | AUCi |

| 137f | Pinna et al | 2014 | DepressionDE | 104 | .07 | AUCg |

| 137g | Pinna et al | 2014 | PTSDPT | 104 | .60 | AUCi |

| 137h | Pinna et al | 2014 | PTSDPT | 104 | .29 | AUCg |

| 138a | Platje et al | 2013 | AggressionGL | 425 | .10 | AUCi |

| 138b | Platje et al | 2013 | AggressionGL | 425 | .04 | AUCg |

| 138c | Platje et al | 2013 | Rule breakingGL | 425 | .12 | AUCi |

| 138d | Platje et al | 2013 | Rule breakingGL | 425 | .10 | AUCg |

| 139a | Polk et al | 2005 | State negative affectAX | 301 | -.04 | AINC |

| 139b | Polk et al | 2005 | State positive affectPO | 298 | -.02 | AINC |

| 139c | Polk et al | 2005 | Trait negative affect, malesAX | 143 | .27 | AINC |

| 139d | Polk et al | 2005 | Trait negative affect, femalesAX | 158 | -.08 | AINC |

| 139e | Polk et al | 2005 | Trait positive affectPO | 298 | -.08 | AINC |

| 140 | Portella et al | 2005 | NeuroticismAX | 30 | .38 | AUCi |

| 141 | Pruesnner et al | 1999 | Perceived stressGL | 66 | .07 | ACOR |

| 142a | Pruessner et al | 2003 | Chronic stressAX | 39 | .31 | AUCg |

| 142b | Pruessner et al | 2003 | Depressive symptomsDE | 39 | .30 | AUCg |

| 143a | Quevedo et al | 2012 | Adolescent negative life eventsGL | 159 | .00 | ACOR |

| 143b | Quevedo et al | 2012 | Adverse early-life rearingGL | 159 | -.20 | ACOR |

| 143c | Quevedo et al | 2012 | Family negative life eventsGL | 159 | -.15 | ACOR |

| 144a | Quirin et al | 2008 | Attachment anxietyAX | 48 | -.40 | AINC |

| 144b | Quirin et al | 2008 | Self-esteemGL | 48 | -.21 | AINC |

| 144c | Quirin et al | 2008 | Social stressGL | 48 | .22 | AINC |

| 145a | Rademaker et al | 2009 | CooperativenessPO | 107 | .07 | MINC |

| 145b | Rademaker et al | 2009 | CooperativenessPO | 107 | -.18 | AUCg |

| 145c | Rademaker et al | 2009 | Harm avoidanceGL | 107 | .22 | MINC |

| 145d | Rademaker et al | 2009 | Harm avoidanceGL | 107 | .24 | AUCg |

| 145e | Rademaker et al | 2009 | Novelty seekingPO | 107 | .08 | MINC |

| 145f | Rademaker et al | 2009 | Novelty seekingGL | 107 | .04 | AUCg |

| 145g | Rademaker et al | 2009 | PersistencePO | 107 | .05 | MINC |

| 145h | Rademaker et al | 2009 | PersistencePO | 107 | -.11 | AUCg |

| 145i | Rademaker et al | 2009 | Reward dependenceGL | 107 | .15 | MINC |

| 145j | Rademaker et al | 2009 | Reward dependenceGL | 107 | -.05 | AUCg |

| 145k | Rademaker et al | 2009 | Self-directednessPO | 107 | .30 | MINC |

| 145l | Rademaker et al | 2009 | Self-directednessPO | 107 | .10 | AUCg |

| 145m | Rademaker et al | 2009 | Self-transcendencePO | 107 | .05 | MINC |

| 145n | Rademaker et al | 2009 | Self-transcendencePO | 107 | .05 | AUCg |

| 146a | Rane et al | 2012 | Caregiver burdenGL | 33 | .19 | AUCi |

| 146b | Rane et al | 2012 | Caregiver distressGL | 33 | -.06 | AUCi |

| 146c | Rane et al | 2012 | Caregiver stressGL | 58 | .00 | AUCi |

| 146d | Rane et al | 2012 | CaregivingGL | 58 | -.29 | AUGg |

| 147a | Ranjit etal | 2009 | High cynical hostility (vs. low) GL | 936 | -.01 | AINC |

| 147b | Ranjit etal | 2009 | High cynical hostility (vs. mid) GL | 936 | .00 | AINC |

| 147c | Ranjit etal | 2009 | Mid cynical hostility (vs. low) GL | 936 | -.01 | AINC |

| 148a | Rhebergen et al | 2015 | Depression diagnosisDE | 363 | -.12 | AUCi |

| 148b | Rhebergen et al | 2015 | Depression diagnosisDE | 363 | .05 | AUCg |

| 149a | Rickenbach et al | 2014 | Daily stressGL | 73 | -.01 | AINC |

| 149b | Rickenbach et al | 2014 | Depressed affectDE | 73 | -.11 | AINC |

| 149c | Rickenbach et al | 2014 | Functional healthpo | 73 | .07 | AINC |

| 149d | Rickenbach et al | 2014 | Life stressorsGL | 73 | .10 | AINC |

| 150 | Roberts et al | 2004 | Chronic fatigueFA | 91 | -.20 | AUCi |

| 151a | Rohleder et al | 2004 | PTSD symptomsPT | 25 | -.58 | AUCg |

| 151b | Rohleder et al | 2004 | PTSD symptomsPT | 25 | -.40 | MINC |

| 152a | Ruhe et al | 2015 | DepressionDE | 111 | -.02 | AINC |

| 152b | Ruhe et al | 2015 | DepressionDE | 111 | -.08 | AUCg |

| 153 | Ruiz-Robledillo et al | 2013 | Caregiving for offspring with AspergerGL | 107 | .21 | AUCi |

| 154a | Ruiz-Robledillo et al | 2014 | Caregiver burden (non-supported)GL | 12 | -.59 | AUCi |

| 154b | Ruiz-Robledillo et al | 2014 | Caregiver burden (supported)GL | 12 | .61 | AUCi |

| 154c | Ruiz-Robledillo et al | 2014 | Institutional supportGL | 36 | .42 | AUCi |

| 155a | Ruiz-Robledillo et al | 2014 | ResiliencePO | 67 | -.06 | AUCi |

| 155b | Ruiz-Robledillo et al | 2014 | ResiliencePO | 67 | -.57 | AUCg |

| 156a | Ruiz-Robledillo & Moya | 2014 | Caregiving burdenGL | 68 | .11 | AUCi |

| 156b | Ruiz-Robledillo & Moya | 2014 | General mental healthPO | 68 | .23 | AUCg |

| 156c | Ruiz-Robledillo & Moya | 2014 | Emotional intelligence attentionPO | 68 | -.09 | AUCi |

| 156d | Ruiz-Robledillo & Moya | 2014 | Emotional intelligence attentionPO | 68 | .04 | AUCg |

| 156e | Ruiz-Robledillo & Moya | 2014 | Emotional intelligence clarityPO | 68 | -.21 | AUCi |

| 156f | Ruiz-Robledillo & Moya | 2014 | Emotional intelligence clarityPO | 68 | -.50 | AUCg |

| 156g | Ruiz-Robledillo & Moya | 2014 | Emotional intelligence repairPO | 68 | .02 | AUCi |

| 156h | Ruiz-Robledillo & Moya | 2014 | Emotional intelligence repairPO | 68 | -.32 | AUCg |

| 157a | Saridjan et al | 2014 | ExternalizingGL | 296 | -.01 | AINC |

| 157b | Saridjan et al | 2014 | InternalizingDE | 295 | -.07 | AINC |

| 158a | Schlotz et al | 2004 | Chronic worryAX | 219 | .16 | MINC |

| 158b | Schlotz et al | 2004 | Job stressJS | 219 | .16 | MINC |

| 159 | Schulz et al | 1998 | Job stressJS | 85 | .29 | ACOR |

| 160a | Shibuya et al | 2014 | AnxietyAX | 18 | .42 | AINC |

| 160b | Shibuya et al | 2014 | ConfusionGL | 18 | .57 | AINC |

| 160c | Shibuya et al | 2014 | DepressionDE | 18 | .47 | AINC |

| 160d | Shibuya et al | 2014 | FatigueFA | 18 | .48 | AINC |

| 161a | Sjögren et al | 2006 | DepressionDE | 257 | -.06 | AINC |

| 161b | Sjögren et al | 2006 | ExhaustionFA | 257 | -.01 | AINC |

| 161c | Sjögren et al | 2006 | HopelessnessDE | 257 | -.05 | AINC |

| 161d | Sjögren et al | 2006 | Job stressJS | 257 | -.06 | AINC |

| 161e | Sjögren et al | 2006 | Poor social supportGL | 257 | -.04 | AINC |

| 161f | Sjögren et al | 2006 | Self-esteemPO | 257 | .08 | AINC |

| 161g | Sjögren et al | 2006 | Well-beingPO | 257 | .06 | AINC |

| 162 | Sjodin et al | 2012 | Noise annoyance at workJS | 101 | -.19 | AINC |

| 163 | Sjors et al | 2012 | BurnoutFA | 241 | -.04 | AINC |

| 164a | Sjors et al | 2014 | Work stressJS | 180 | -.01 | AUCi |

| 164b | Sjors et al | 2014 | Work stressJS | 180 | -.02 | AUCg |

| 164c | Sjors et al | 2014 | Overall stressGL | 180 | -.14 | AUCi |

| 164d | Sjors et al | 2014 | Overall stressGL | 180 | -.13 | AUCg |

| 164e | Sjors et al | 2014 | Home stressGL | 180 | -.12 | AUCi |

| 164f | Sjors et al | 2014 | Home stressGL | 180 | -.20 | AUCg |

| 164g | Sjors et al | 2014 | Home stress, malesGL | 86 | .00 | AUCg |

| 164h | Sjors et al | 2014 | Home stress, femalesGL | 94 | -.23 | AUCg |

| 165 | Sjors et al | 2015 | Exhaustion FA | 220 | -.15 | AINC |

| 166a | Sladek et al | 2015 | Daily social connectionPO | 71 | .13 | AINC |

| 166b | Sladek et al | 2015 | Depressive symptomsDE | 71 | -.17 | AINC |

| 166c | Sladek et al | 2015 | LonelinessGL | 71 | -.23 | AINC |

| 167a | Smeets et al | 2007 | Continuous sexual abuse memoryPT | 15 | .00 | AUCi |

| 167b | Smeets et al | 2007 | Recovered sexual abuse memoryPT | 16 | .00 | AUCi |

| 167c | Smeets et al | 2007 | Repressed sexual abuse memoryPT | 17 | .00 | AUCi |

| 168a | Smyth et al | 2015 | Trait well-beingPO | 44 | -.19 | AUCg |

| 168b | Smyth et al | 2015 | Trait well-beingPO | 44 | -.07 | MINC |

| 169a | Sonnenschein et al | 2007 | General exhaustionFA | 42 | -.13 | AUCi |

| 169b | Sonnenschein et al | 2007 | General exhaustionFA | 42 | .06 | AUCg |

| 169c | Sonnenschein et al | 2007 | State exhaustionFA | 42 | -.37 | AUCi |

| 169d | Sonnenschein et al | 2007 | State exhaustionFA | 42 | -.27 | AUCg |

| 170a | Stafford et al | 2013 | Divorced status <3 yearsGL | 2229 | .00 | AINC |

| 170b | Stafford et al | 2013 | Divorced status >3 yearsGL | 2229 | -.04 | AINC |

| 170c | Stafford et al | 2013 | Long-term living aloneGL | 2229 | .00 | AINC |

| 170d | Stafford et al | 2013 | Newly living aloneGL | 2229 | .00 | AINC |

| 170e | Stafford et al | 2013 | Reduction in social networkGL | 2229 | .00 | AINC |

| 170f | Stafford et al | 2013 | Single, never married statusGL | 2229 | .00 | AINC |

| 170g | Stafford et al | 2013 | Small social networkGL | 2229 | .00 | AINC |

| 170h | Stafford et al | 2013 | Widowed <3 yearsGL | 2229 | .00 | AINC |

| 170i | Stafford et al | 2013 | Widowed >3 yearsGL | 2229 | .04 | AINC |

| 171a | Stalder et al | 2011 | Difficulties in emotion regulationGL | 43 | .22 | AUCi |

| 171b | Stalder et al | 2011 | Perceived stressGL | 43 | .29 | AUCi |

| 172 | Stawski et al | 2013 | Frequent daily stressorsGL | 1694 | -.05 | AUCg |

| 173 | Steinheuser et al | 2014 | Urban upbringingGL | 116 | -.18 | ACOR |

| 174a | Steptoe et al | 2004 | Job stress (over-commitment), malesJS | 83 | .23 | AINC |

| 174b | Steptoe et al | 2004 | Job stress (over-committment), malesJS | 83 | .12 | AUCg |

| 174c | Steptoe et al | 2004 | Job stress (over-committment), femalesJS | 81 | .12 | AINC |

| 174d | Steptoe et al | 2004 | Job stress (over-committment), femalesJS | 81 | .05 | AUCg |

| 175a | Steptoe, Owen, et al | 2004 | LonelinessGL | 163 | .13 | AINC |

| 175b | Steptoe, Owen, et al | 2004 | LonelinessGL | 163 | .14 | AUCg |

| 176a | Steptoe et al | 2005 | Chronic economic stress, malesAX | 88 | .18 | AINC |

| 176b | Steptoe et al | 2005 | Chronic economic stress, malesAX | 88 | .27 | AUCg |

| 176c | Steptoe et al | 2005 | Chronic economic stress, femalesAX | 72 | .00 | AINC |

| 176d | Steptoe et al | 2005 | Chronic economic stress, femalesAX | 72 | .28 | AUCg |

| 177a | Steptoe et al | 2007 | State happinessPO | 73 | -.20 | AUCi |

| 177b | Steptoe et al | 2007 | State happinessPO | 73 | -.36 | AUCg |

| 178 | Stetler et al | 2005 | DepressionDE | 69 | -.47 | AUCg |

| 179a | Strahler et al | 2010 | Somatic trait anxietyAX | 17 | -.04 | AUCg |

| 179b | Strahler et al | 2010 | Trait worryAX | 17 | -.15 | AUCg |

| 180 | Tang et al | 2014 | ShynessGL | 24 | -.29 | ACOR |

| 181a | terWolbeek et al | 2007 | FatigueFA | 132 | .00 | AINC |

| 181b | terWolbeek et al | 2007 | FatigueFA | 132 | .00 | AUCg |

| 182a | Therrien et al | 2007 | Depression, malesDE | 50 | -.17 | AINC |

| 182b | Therrien et al | 2007 | Depression, femalesDE | 28 | -.22 | AINC |

| 182c | Therrien et al | 2007 | Trait anxiety, malesAX | 50 | -.22 | AINC |

| 182d | Therrien et al | 2007 | Trait anxiety, femalesAX | 28 | -.42 | AINC |

| 183 | Thomas et al | 2012 | CaregivingGL | 45 | -.21 | AINC |

| 184 | Thorn et al | 2011 | Seasonal affective disorderDE | 52 | -.25 | ACOR |

| 185a | Tomiyama et al | 2014 | Weight stigma consciousnessGL | 42 | .23 | AINC |

| 185b | Tomiyama et al | 2014 | Weight stigma frequencyGL | 41 | .30 | AINC |

| 186 | Tops et al | 2008 | Depressive moodDE | 194 | .14 | AUCi |

| 187 | Tu et al | 2013 | DepressionDE | 121 | -.18 | Slope |

| 188 | Ulrike et al | 2013 | DepressionDE | 131 | .08 | ACOR |

| 189a | Vammen et al | 2014 | Depressive symptoms (2009 sample)DE | 474 | -.06 | MINC |

| 189b | Vammen et al | 2014 | Depressive symptoms (2007 sample)DE | 376 | -.06 | MINC |

| 189c | Vammen et al | 2014 | Clinical depression (2009 sample)DE | 297 | -.06 | MINC |

| 189d | Vammen et al | 2014 | Clinical depression (2007 sample)DE | 214 | -.07 | MINC |

| 190a | van Liempt et al | 2013 | Trauma with PTSDPT | 24 | -.15 | AUCg |

| 190b | van Liempt et al | 2013 | Trauma without PTSDGL | 29 | .24 | AUCg |

| 191a | van Santen et al | 2011 | AgreeablenessPO | 337 | .04 | AUCi |

| 191b | van Santen et al | 2011 | AgreeablenessPO | 337 | .00 | AUCg |

| 191c | van Santen et al | 2011 | Anxiety sensitivityAX | 337 | .07 | AUCi |

| 191d | van Santen et al | 2011 | Anxiety sensitivityAX | 337 | .04 | AUCg |

| 191e | van Santen et al | 2011 | ConscientiousnessPO | 337 | -.08 | AUCi |

| 191f | van Santen et al | 2011 | ConscientiousnessPO | 337 | -.02 | AUCg |

| 191g | van Santen et al | 2011 | ExtraversionPO | 337 | -.09 | AUCi |

| 191h | van Santen et al | 2011 | ExtraversionPO | 337 | -.01 | AUCg |

| 191i | van Santen et al | 2011 | MasteryPO | 337 | -.10 | AUCi |

| 191j | van Santen et al | 2011 | MasteryPO | 337 | .01 | AUCg |

| 191k | van Santen et al | 2011 | NeuroticismAX | 337 | .07 | AUCi |

| 191l | van Santen et al | 2011 | NeuroticismAX | 337 | .08 | AUCg |

| 191m | van Santen et al | 2011 | Openness to experiencePO | 337 | -.06 | AUCi |

| 191n | van Santen et al | 2011 | Openness to experiencePO | 337 | -.04 | AUCg |

| 192a | Vargas et al | 2014 | Anticipatory stressGL | 58 | .34 | AINC |

| 192b | Vargas et al | 2014 | Previous day stressGL | 58 | -.17 | AINC |

| 193a | Veen et al | 2011 | DepressionDE | 118 | .27 | AINC |

| 193b | Veen et al | 2011 | DepressionDE | 118 | .09 | AUCg |

| 193c | Veen et al | 2011 | AnxietyAX | 118 | .06 | AINC |

| 193d | Veen et al | 2011 | AnxietyAX | 118 | .03 | AUCg |

| 193e | Veen et al | 2011 | Comorbid depression & anxietyDE | 118 | .04 | AINC |

| 193f | Veen et al | 2011 | Comorbid depression & anxietyDE | 118 | .10 | AUCg |

| 194a | von Polier et al | 2013 | Callous unemotionalityGL | 75 | -.13 | AUCg |

| 194b | von Polier et al | 2013 | HyperactivityGL | 75 | -.26 | AUCg |

| 195a | Vreeburg et al | 2009 | Current MDD (vs. control)DE | 1009 | .04 | AUCi |

| 195b | Vreeburg et al | 2009 | Current MDD (vs. control)DE | 1009 | .11 | AUCg |

| 195c | Vreeburg et al | 2009 | Remitted MDD (vs. control)DE | 887 | .09 | AUCi |

| 195d | Vreeburg et al | 2009 | Remitted MDD (vs. control)DE | 887 | .09 | AUCg |

| 196a | Vreeburg, Zitman, et al | 2010 | Current anxiety disorderAX | 1116 | .05 | AUCi |

| 196b | Vreeburg, Zitman, et al | 2010 | Current anxiety disorderAX | 1116 | .09 | AUCg |

| 196c | Vreeburg, Zitman, et al | 2010 | Remitted anxiety disorderAX | 653 | .03 | AUCi |

| 196d | Vreeburg, Zitman, et al | 2010 | Remitted anxiety disorderAX | 653 | .05 | AUCg |

| 197a | Vreeburg et al | 2010 | Diagnosed parental depression historyDE | 256 | .13 | AUCi |

| 197b | Vreeburg et al | 2010 | Diagnosed parental depression historyDE | 256 | .15 | AUCg |

| 197c | Vreeburg et al | 2010 | Self-reported parental depression historyDE | 303 | .05 | AUCi |

| 197d | Vreeburg et al | 2010 | Self-reported parental depression historyDE | 303 | .01 | AUCg |

| 198 | Wahbeh et al | 2008 | Caregiver stressGL | 30 | .31 | AINC |

| 199 | Wahbeh et al | 2013 | PTSD (vs. control)PT | 71 | -.12 | AINC |

| 200 | Walker et al | 2011 | Trait anxietyAX | 40 | -.35 | AUCg |

| 201a | Wardenaar et al | 2011 | Anhedonic depressionDE | 1029 | .02 | AUCi |

| 201b | Wardenaar et al | 2011 | Anhedonic depressionDE | 1029 | .02 | AUCg |

| 201c | Wardenaar et al | 2011 | Anxious arousalAX | 1029 | .02 | AUCi |

| 201d | Wardenaar et al | 2011 | Anxious arousalAX | 1029 | .02 | AUCg |

| 201e | Wardenaar et al | 2011 | General distressGL | 1029 | .04 | AUCi |

| 201f | Wardenaar et al | 2011 | General distressGL | 1029 | .04 | AUCg |

| 202a | Weekes et al | 2008 | Examination stress, malesGL | 31 | .00 | ACOR |

| 202b | Weekes et al | 2008 | Examination stress, femalesGL | 35 | .51 | ACOR |

| 203 | Weik et al | 2010 | Exam stressGL | 24 | -.19 | AINC |

| 204 | Wessa et al | 2006 | PTSD symptomsPT | 63 | -.38 | AUCg |

| 205a | Wilcox et al | 2014 | DepressionDE | 460 | .00 | AUCi |

| 205b | Wilcox et al | 2014 | Quality of lifePO | 460 | .00 | AUCi |

| 206a | Williams et al | 2013 | Family functioning (aff. involvement), momPO | 27 | .00 | Slope |

| 206b | Williams et al | 2013 | Family functioning (aff. involvement), childPO | 27 | .00 | Slope |

| 206c | Williams et al | 2013 | Family functioning (aff. responses), momPO | 27 | .00 | Slope |

| 206d | Williams et al | 2013 | Family functioning (aff. responses), childPO | 27 | .00 | Slope |

| 206e | Williams et al | 2013 | Family functioning (behavior control), momGL | 27 | .00 | Slope |

| 206f | Williams et al | 2013 | Family functioning (behavior control), childGL | 27 | .00 | Slope |

| 206g | Williams et al | 2013 | Family functioning (communication), childPO | 27 | .00 | Slope |

| 206h | Williams et al | 2013 | Family functioning (communication), momPO | 27 | .49 | Slope |

| 206i | Williams et al | 2013 | Family functioning (problem solving), momPO | 27 | .00 | Slope |

| 206j | Williams et al | 2013 | Family functioning (problem solving), childPO | 27 | .00 | Slope |

| 206k | Williams et al | 2013 | Family functioning (roles), momPO | 27 | .00 | Slope |

| 206l | Williams et al | 2013 | Family functioning (roles), childPO | 27 | .41 | Slope |

| 207a | Wirth et al | 2011 | Depressive symptomsDE | 123 | .09 | AUCi |

| 207b | Wirth et al | 2011 | Depressive symptomsDE | 123 | .01 | AUCg |

| 207c | Wirth et al | 2011 | Shift workJS | 123 | .05 | AUCi |

| 207d | Wirth et al | 2011 | Shift workJS | 123 | -.07 | AUCg |

| 208a | Wolfram et al | 2013 | BurnoutFA | 21 | .31 | AUCg |

| 208b | Wolfram et al | 2013 | DepersonalizationJS | 21 | .40 | AUCg |

| 208c | Wolfram et al | 2013 | Effort-reward imbalanceJS | 21 | .31 | AUCg |

| 208d | Wolfram et al | 2013 | Emotional exhaustionFA | 21 | .22 | AUCg |

| 208e | Wolfram et al | 2013 | Lack of accomplishmentJS | 21 | .15 | AUCg |

| 208f | Wolfram et al | 2013 | Over-committmentJS | 21 | .02 | AUCg |

| 209a | Wright et al | 2005 | Financial strainGL | 76 | .17 | AINC |

| 209b | Wright et al | 2005 | Financial strainGL | 76 | .13 | AUCg |

| 210a | Wüst et al | 2000 | Chronic worryAX | 102 | .17 | ACOR |

| 210b | Wüst et al | 2000 | Job stress (overload)JS | 102 | .00 | ACOR |

| 210c | Wüst et al | 2000 | Job stress (discontent)JS | 102 | .00 | ACOR |

| 210d | Wüst et al | 2000 | Lack of social recognitionGL | 102 | .22 | ACOR |

| 210e | Wüst et al | 2000 | Social stressGL | 102 | .21 | ACOR |

| 210f | Wüst et al | 2000 | Self-efficacyPO | 104 | -.19 | MINC |

| 210g | Wüst et al | 2000 | Self-efficacyPO | 104 | -.06 | AUCg |

| 210h | Wüst et al | 2000 | Self-esteemPO | 104 | -.16 | MINC |

| 210i | Wüst et al | 2000 | Self-esteemPO | 104 | -.01 | AUCg |

| 211a | Zeiders et al | 2012 | AcculturationPO | 100 | .15 | AINC |

| 211b | Zeiders et al | 2012 | Daily life stressGL | 100 | .12 | AINC |

| 211c | Zeiders et al | 2012 | MDD symptomsDE | 100 | .04 | AINC |

| 211d | Zeiders et al | 2012 | Family incomePO | 100 | .07 | AINC |

| 211e | Zeiders et al | 2012 | Life stressorsGL | 100 | .13 | AINC |

| 211f | Zeiders et al | 2012 | Perceived discriminationGL | 100 | .13 | AINC |

| 212 | Zoccola et al | 2011 | Trait perseverative cognitionAX | 119 | .03 | AINC |

Notes: Italicized findings indicate that they were drawn from the Chida & Steptoe (2009) meta-analysis. Bolded findings indicate that they were included in p-curves for their respective sets.

Abbreviations: N = sample size, r = correlation; ADHD = Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CD = conduct disorder; DC = demand/control; ERI = effort/reward imbalance; MDD = major depressive disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder

Abbreviations for outcome type superscripts JS = job stress, GL = general life stress; DE = depression; AX = anxiety/neuroticism/negative affect, FA = fatigue/burnout/exhaustion, PT = posttraumatic stress, and PO = positive psychosocial traits

Abbreviations for measure: CARi was assessed using the following methods: Absolute increase of cortisol during the waking period (AINC), area of cortisol increase under the curve (AUCi), the mean value of cortisol values post-awakening minus wakening value (MINC), absolute value post-awakening evaluated by repeated analysis of variables (ACOR), slope of cortisol increase (slope), and ratio of cortisol at time 1 divided by cortisol at time 0 (T1/T0). AUCw was assessed using the following methods: area under the curve relative to ground (AUCg) and 30-minute absolute cortisol value (30min).

Findings Associating Worse Psychosocial Functioning with Higher CARi