Abstract

Background and aims

There is evidence that low risk drinking is possible during the course of alcohol treatment and can be maintained following treatment. Our aim was to identify characteristics associated with low risk drinking during treatment in a large sample of individuals as they received treatment for alcohol dependence.

Design

Integrated analysis of data from the COMBINE study, Project MATCH, and the United Kingdom Alcohol Treatment Trial using repeated measures latent class analysis to identify patterns of drinking and predictors of low risk drinking patterns during treatment.

Setting

USA and United Kingdom.

Participants

Patients (n=3589) with alcohol dependence receiving treatment in an alcohol clinical trial were primarily male (73.0%), White (82.0%), and non-married (41.7%), with an average age of 42.0 (SD=10.7).

Measurements

Self-reported weekly alcohol consumption during treatment was assessed using the Form-90[1] and validated with biological verification or collateral informants.

Findings

Seven patterns of drinking during treatment were identified: persistent heavy drinking (18.7% of the sample), increasing heavy drinking (9.6%), heavy and low risk drinking (6.7%), heavy drinking alternating with abstinence (7.9%), low risk drinking (6.8%), increasing low risk drinking (10.5%), and abstinence (39.8%). Lower alcohol dependence severity and fewer drinks per day at baseline significantly predicted low risk drinking patterns (e.g., each additional drink prior to baseline predicted a 27% increase in the odds of expected classification in heavy drinking versus low risk drinking patterns; Odds Ratio=1.27 (95% CI: 1.10, 1.47, p=0.002)). Greater negative mood and more heavy drinkers in the social network were significant predictors of expected membership in heavier drinking patterns.

Conclusions

Low risk drinking is achievable for some individuals as they undergo treatment for alcohol dependence. Individuals with lower dependence severity, less baseline drinking, fewer negative mood symptoms, and fewer heavy drinkers in their social networks have a higher probability of achieving low risk drinking during treatment.

Keywords: Low risk drinking, alcohol treatment, repeated measures latent class analysis, dependence severity, moderation, controlled drinking, alcohol dependence

Introduction

Abstinence from alcohol has historically been viewed as the most desirable outcome for alcohol treatment, yet not wanting to stop drinking completely is one of the primary reasons why the majority of individuals with alcohol problems do not seek treatment[2, 3]. However, there is growing evidence that low risk drinking, often defined by not exceeding low risk drinking limits (e.g., no more than 3 drinks per occasion for women and 4 drinks per occasion for men[4]), is possible during the course of treatment, and low risk drinking can be maintained for up to several years following treatment[5–9]. Further, the United States Food and Drug Administration has recommended “no heavy drinking days”, as an alternative primary endpoint to abstinence in the evaluation of medications for alcohol dependence[10].

Previous analyses of data[6] from three alcohol clinical trials (n=3,851) identified seven patterns of drinking during the course of treatment: (1) persistent heavy drinking, (2) increasing heavy drinking, (3) heavy and low risk drinking, (4) heavy drinking alternating with abstinence, (5) low risk drinking, (6) increasing low risk drinking, and (7) abstinence. An examination of outcomes up to 12 months following treatment indicated that those with the heaviest drinking patterns during treatment had the worst outcomes with respect to drinking consequences and self-reported physical and mental health, whereas those with low risk drinking patterns had consistently better long term outcomes. Low risk drinkers during treatment did not differ from abstainers with respect to outcomes up to 12 months following treatment[6].

Several prior studies, mostly based on small samples, have examined the patient characteristics that predict low risk drinking (i.e., controlled drinking)[11–15], and findings have been mixed. For example, lower severity of alcohol dependence has been identified as a predictor of low risk drinking in many studies[15–17], but not others[12, 14, 18]. Similar inconsistencies have been found for the role of psychiatric problems and mood disturbances[19–21], as well as baseline drinking patterns[14, 22], social network drinking [23, 24], and various demographic factors[11, 23, 25]. Importantly, these prior studies included small samples from only one treatment site, relied on static definitions of low risk drinking (e.g., never exceeding a drinking threshold), and have mostly focused, with only two exceptions[12, 14], on long term outcomes after varying lengths of treatment[13 15–16, 19]. With respect to the last two points, clinicians are not typically interested in patients never exceeding a certain drinking threshold and are often far more interested in the overall patterns of drinking during treatment. To address these limitations, the current study examined which patient characteristics predicted low risk drinking patterns during treatment using a large sample of individuals in three clinical trials for alcohol dependence across 27 treatment sites in two countries.

Methods

The data for this study were drawn from 3 randomized clinical trials for alcohol dependence (n=3,851)[6]. In the combined sample, patients were primarily male (73.0%), White (82.0%), and non-married (41.7%), with an average age of 42.0 (SD=10.7).

Participants

COMBINE Study

The COMBINE study[26] randomized participants (n=1,383) from 11 research sites across the US into medication management (MM) or combined behavioral intervention (CBI) and randomization to combinations of medications (acamprosate, naltrexone, placebo). Treatment occurred over 16 weeks. Inclusion criteria included being at least 18 years old, at least four days of abstinence prior to treatment, meeting criteria for alcohol dependence in the past year, and being literate in English. Exclusion criteria included comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, other illicit drug dependence, and any medical conditions that were contraindicated for naltrexone and acamprosate. The majority of participants in the COMBINE study (60.3%) expressed a preference for an abstinence goal during the baseline assessment.

Project MATCH

Project MATCH[27] randomized outpatients (n=952) and aftercare patients (n=774) from 9 research sites across the US into 3 treatment conditions: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET), or Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF). Treatment occurred over 12 weeks. Inclusion criteria included being at least 18 years old, meeting criteria for alcohol dependence in the past year, and being able to read at the 6th grade level. Exclusion criteria included comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, severe cognitive impairment, residential instability, and other illicit drug dependence. Participants were not assessed with respect to drinking goals prior to starting treatment.

United Kingdom Alcohol Treatment Trial (UKATT)

UKATT[28] recruited participants (n=742) across 7 sites in the United Kingdom. Patients were randomized into MET or Social Behavior and Network Therapy (SBNT). Treatment occurred over 12 weeks. Inclusion criteria included being over 16, seeking help for alcohol problems, and being literate in the English language. Exclusion criteria included comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, severe cognitive impairment, and residential instability. Treatment in UKATT was geared toward either abstinence or moderated drinking. Among patients in UKATT, 54.3% initially expressed a preference for an abstinence goal.

Measures

Weekly alcohol consumption during treatment was assessed in all studies by calendar-based methods using the Form-90[1]. COMBINE and UKATT provided a validity check of self-reported drinking by biological verification via % carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (%CDT) in COMBINE and γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) in COMBINE and UKATT. Project MATCH provided a validity check of self-reported drinking by corroborating the self-report data with collateral interviews. For all analyses, we created 3 categories of weekly drinking during treatment: abstinent (no drinking during a given week); low risk drinking (1 or more days with less than 4/5 drinks and no heavy drinking days during a given week); and heavy drinking (at least 1 day with 4/5 or more drinks during a given week).

Predictors of drinking patterns included (1) demographic variables (age, sex, race, marital status), (2) percentage of heavy drinkers in the social network, (3) drinks per day over the week prior to the baseline assessment in MATCH and UKATT and the week prior to the 4 days of abstinence in the COMBINE study, (4) baseline alcohol dependence severity, and (5) negative mood symptoms. Descriptives for each of the predictors by study and in the pooled sample are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptives for Demographics and Baseline Characteristics by Study and in the Pooled Sample

| Demographic characteristic | COMBINE | MATCH | UKATT | Pooled Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 1383 | 1726 | 742 | 3851 |

| Sex - % Male | 69.1% | 75.7% | 74.1% | 73.0% |

| Age – Mean (SD) | 44.4 (10.2) | 40.2 (10.9) | 41.6 (10.1) | 42.0 (10.7) |

| Ethnicity - % White | 76.8% | 80.0% | 95.6% | 81.8% |

| Marital status - % Married/cohabitating | 46.3% | 41.4% | 54.1% | 41.7% |

|

| ||||

| Baseline Characteristics Mean (SD) | COMBINE | MATCH | UKATT | Pooled Sample |

|

| ||||

| Percent heavy drinkers in social network | 9.9% (16%) | 17.4% (19%) | 16.4% (20%) | 14.5% (19%) |

| Drinks per day in the week prior to baseline | 7.2 (6.4) | 11.0 (10.2) | 10.5 (8.8) | 9.5 (8.9) |

| Alcohol dependence severity scale score | −0.2 (0.8) | −0.1 (0.9) | 0.06 (0.8) | −0.1 (0.9) |

| Negative mood scale scores | −0.18 (0.9) | 0.07 (0.7) | 1.58 (0.6) | 0.27 (1.0) |

Social network heavy drinking was assessed by the Important People and Activities Inventory[29] measure in all three studies. A measure of alcohol dependence severity and a measure of negative mood symptoms were derived using integrative data analysis[30]. Twenty items assessing alcohol dependence severity (Supplementary Table 1) were obtained via the Alcohol Dependence Scale[15] in MATCH and COMBINE, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM) in MATCH (DSM-III-R[32]) and COMBINE (DSM-IV[33]), and the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire[34] in UKATT. Six items assessing negative mood symptoms (Supplementary Table 1) were obtained via the Beck Depression Inventory[35] in MATCH, the Brief Symptom Inventory[36] in COMBINE, and the General Health Questionnaire[37] in UKATT.

Statistical Analyses

Repeated measures latent class analysis (RMLCA)[38] was used to identify seven classes (i.e., patterns) of drinking across 12 weeks of treatment, as described elsewhere[6]. RMLCA is a latent variable mixture model in which the indicators of the latent class are repeated measures (e.g., weekly drinking). The current study examined demographic characteristics (age, sex (male=1), marital status (married=1), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White=1)), baseline percentage of heavy drinkers in the social network, drinks per day in the week prior to the baseline assessment, baseline alcohol dependence severity, and baseline negative mood symptoms, as well as all possible two-way and three-way interactions, as predictors of the seven patterns of drinking during treatment. We initially tested all possible two-way and three-way interactions using an a priori criterion for interaction effects of p<.01. However, no three-way interactions were retained and only two of the two-way interactions were retained: (1) age-by-baseline drinking, and (2) age-by-mood symptoms. Significant two-way interactions were probed using simple slopes analysis[39]. In addition, the effect of study membership and two-way interactions between study membership and covariates were also included in all models (Supplementary Table 2). Similar to our previous analyses[6] we did not include treatment condition as a covariate in the models because we were primarily interested in patterns of change regardless of treatment condition. In addition, the three studies included 10 different treatments, however participants in any given study could only be assigned to a limited set of treatment options (e.g., placebo, acamprosate, naltrexone, MM, or CBI in COMBINE; CBT, MET, or TSF in MATCH; MET or SBNT in UKATT).

Multinomial logistic regressions within the RMLCA model were estimated to assess the association between baseline patient characteristics and drinking patterns. Specifically, baseline characteristics were used to predict expected class membership in each of the latent classes of the RMLCA model. All models were estimated using Mplus version 7.3[40]. The Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) and sample-size adjusted BIC (aBIC) were examined to select the RMLCA model with the best overall model fit, where lower BIC and aBIC indicate a better fitting model[41]. Classification precision (defined by relative entropy) was used to evaluate how well the final latent class solution classified individuals into latent classes[42].Considering the complex sampling design in each of the studies (i.e., recruitment from multiple sites), all parameters were estimated using a weighted maximum likelihood function and all standard errors were computed using a sandwich estimator (i.e., MLR in Mplus[43]). The robust maximum likelihood estimator provides the estimated variance-covariance matrix for the available drinking data and, therefore, all available drinking data during treatment were included in the models. Mplus could not accommodate missing data in the predictors (n=262; 6.8% of the full sample). The final model was re-estimated using multiple imputation; however, results from that model were not substantively changed from the results derived via MLR, thus we report the maximum likelihood estimation results (n=3589).

Results

Repeated Measures Latent Class Models

As reported previously[6], repeated measures latent class models with 2 to 15 classes were estimated and a 7-class model was retained as the optimal solution based on the BIC, aBIC, entropy, and substantive interpretation of the latent classes. The 7-class model also provided an optimal solution in the current study when covariate predictors were included in the model. A description of each of the classes was derived by examining the probabilities of abstinence, low risk drinking, or heavy drinking within each class (Table 2). The 7-classes differed significantly in the expected direction on biological measures of %CDT and GGT in COMBINE and UKATT, respectively, such that the abstainers and low risk drinkers (Classes 5–7) had significantly lower %CDT and GGT than the classes with more self-reported drinking (Classes 1–4).

Table 2.

Probability of Weekly Abstinence, Low Risk Drinking, and Heavy Drinking during 12 Weeks of Treatment by Latent Classes

| Abstinence | Low Risk Drinking | Heavy Drinking | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (18.7%) Persistent Heavy Drinkers | |||

| Week 1 | 0.076 | 0.019 | 0.905 |

| Week 2 | 0.043 | 0.009 | 0.948 |

| Week 3 | 0.018 | 0.004 | 0.978 |

| Week 4 | 0.020 | 0.006 | 0.975 |

| Week 5 | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.986 |

| Week 6 | 0.016 | 0.005 | 0.979 |

| Week 7 | 0.014 | 0.002 | 0.984 |

| Week 8 | 0.017 | 0.002 | 0.981 |

| Week 9 | 0.014 | 0.010 | 0.975 |

| Week 10 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.984 |

| Week 11 | 0.029 | 0.008 | 0.963 |

| Week 12 | 0.045 | 0.020 | 0.935 |

| Class 2 (9.6%) Relapse to Heavy Drinking | |||

| Week 1 | 0.913 | 0.011 | 0.075 |

| Week 2 | 0.882 | 0.014 | 0.105 |

| Week 3 | 0.791 | 0.064 | 0.145 |

| Week 4 | 0.675 | 0.070 | 0.255 |

| Week 5 | 0.562 | 0.046 | 0.392 |

| Week 6 | 0.485 | 0.045 | 0.470 |

| Week 7 | 0.395 | 0.048 | 0.557 |

| Week 8 | 0.346 | 0.053 | 0.602 |

| Week 9 | 0.290 | 0.053 | 0.657 |

| Week 10 | 0.207 | 0.037 | 0.756 |

| Week 11 | 0.246 | 0.045 | 0.709 |

| Week 12 | 0.251 | 0.043 | 0.706 |

| Class 3 (6.7%) Mixed Heavy and Low Risk Drinking | |||

| Week 1 | 0.108 | 0.347 | 0.545 |

| Week 2 | 0.052 | 0.333 | 0.616 |

| Week 3 | 0.099 | 0.308 | 0.593 |

| Week 4 | 0.054 | 0.334 | 0.611 |

| Week 5 | 0.049 | 0.343 | 0.608 |

| Week 6 | 0.073 | 0.259 | 0.669 |

| Week 7 | 0.061 | 0.267 | 0.673 |

| Week 8 | 0.080 | 0.317 | 0.603 |

| Week 9 | 0.037 | 0.254 | 0.709 |

| Week 10 | 0.110 | 0.309 | 0.581 |

| Week 11 | 0.050 | 0.373 | 0.576 |

| Week 12 | 0.077 | 0.320 | 0.603 |

| Class 4 (7.9%) Heavy Drinking and Abstinence | |||

| Week 1 | 0.214 | 0.044 | 0.742 |

| Week 2 | 0.150 | 0.032 | 0.818 |

| Week 3 | 0.242 | 0.045 | 0.713 |

| Week 4 | 0.306 | 0.061 | 0.633 |

| Week 5 | 0.387 | 0.033 | 0.580 |

| Week 6 | 0.490 | 0.021 | 0.489 |

| Week 7 | 0.552 | 0.044 | 0.404 |

| Week 8 | 0.671 | 0.059 | 0.269 |

| Week 9 | 0.744 | 0.051 | 0.205 |

| Week 10 | 0.847 | 0.045 | 0.108 |

| Week 11 | 0.786 | 0.035 | 0.178 |

| Week 12 | 0.764 | 0.024 | 0.212 |

| Class 5 (6.8%) Consistent Low Risk Drinking | |||

| Week 1 | 0.096 | 0.801 | 0.103 |

| Week 2 | 0.049 | 0.868 | 0.083 |

| Week 3 | 0.031 | 0.898 | 0.071 |

| Week 4 | 0.044 | 0.882 | 0.074 |

| Week 5 | 0.016 | 0.900 | 0.084 |

| Week 6 | 0.063 | 0.864 | 0.073 |

| Week 7 | 0.072 | 0.846 | 0.082 |

| Week 8 | 0.068 | 0.836 | 0.097 |

| Week 9 | 0.049 | 0.819 | 0.132 |

| Week 10 | 0.041 | 0.842 | 0.116 |

| Week 11 | 0.069 | 0.834 | 0.097 |

| Week 12 | 0.087 | 0.807 | 0.106 |

| Class 6 (10.5%) Abstinence and Low Risk Drinking | |||

| Week 1 | 0.732 | 0.220 | 0.048 |

| Week 2 | 0.653 | 0.266 | 0.080 |

| Week 3 | 0.659 | 0.279 | 0.062 |

| Week 4 | 0.607 | 0.313 | 0.080 |

| Week 5 | 0.666 | 0.277 | 0.057 |

| Week 6 | 0.610 | 0.313 | 0.077 |

| Week 7 | 0.594 | 0.308 | 0.098 |

| Week 8 | 0.630 | 0.298 | 0.072 |

| Week 9 | 0.585 | 0.313 | 0.101 |

| Week 10 | 0.539 | 0.359 | 0.102 |

| Week 11 | 0.594 | 0.336 | 0.070 |

| Class 7 (39.8%) Abstainers | |||

| Week 1 | 0.946 | 0.022 | 0.032 |

| Week 2 | 0.955 | 0.018 | 0.026 |

| Week 3 | 0.972 | 0.014 | 0.013 |

| Week 4 | 0.969 | 0.008 | 0.022 |

| Week 5 | 0.970 | 0.011 | 0.018 |

| Week 6 | 0.964 | 0.011 | 0.025 |

| Week 7 | 0.975 | 0.006 | 0.019 |

| Week 8 | 0.968 | 0.008 | 0.025 |

| Week 9 | 0.979 | 0.009 | 0.012 |

| Week 10 | 0.959 | 0.014 | 0.027 |

| Week 11 | 0.965 | 0.010 | 0.026 |

| Week 12 | 0.942 | 0.020 | 0.038 |

Class 1 (18.7% of the sample), “persistent heavy drinking”, reported a high probability of heavy drinking with average drinks per drinking day (DDD) of 10.59 (SD=6.27) and average percent drinking days (PDD) of 69% (SD=26.6%) during treatment. Class 2 (9.6% of the sample), “relapse-to-heavy drinking”, reported abstinence initially and a high probability of heavy drinking by the end of treatment with average DDD of 11.88 (SD=7.41) and average PDD of 25.2% (SD=18.9%). Class 3 (6.7% of the sample), “mixed heavy and low risk drinking”, reported a mix of heavy and low risk drinking with average DDD of 5.48 (SD=3.44) and average PDD of 49.2% (SD=24.0%) across the treatment period. Class 4 (7.9% of the sample), “heavy drinking-to-abstinence”, reported heavy drinking initially and a high probability of abstinence by the end of treatment with average DDD of 9.0 (SD=8.5) during the first six weeks of treatment and average DDD of 2.5 (SD=5.4) during the last week of treatment. Class 5 (6.8% of the sample), “consistent low drinking”, reported low risk drinking throughout treatment with average DDD of 2.85 (SD=1.60) and average PDD of 49.4% (SD=26.2%). Class 6 (10.5% of the sample), “abstinence-to-low risk drinking”, reported a high probability of abstinence initially and an increasing probability of low-risk drinking with average DDD of 3.52 (SD=2.29) and average PDD of 10.7% (SD=9.2%). Class 7 (39.8% of the sample), “abstainers”, reported a high probability of abstinence throughout treatment. As described previously[6], individuals in the low risk drinking classes (Classes 5 and 6; 17.3% of the total sample) were not significantly different (ps>0.05) from abstainers (Class 7), with respect to post-treatment functioning on measures of drinking consequences up to 12-months post-treatment and mental health up to 9-months post-treatment.

Baseline Predictors of Drinking Classes during Treatment

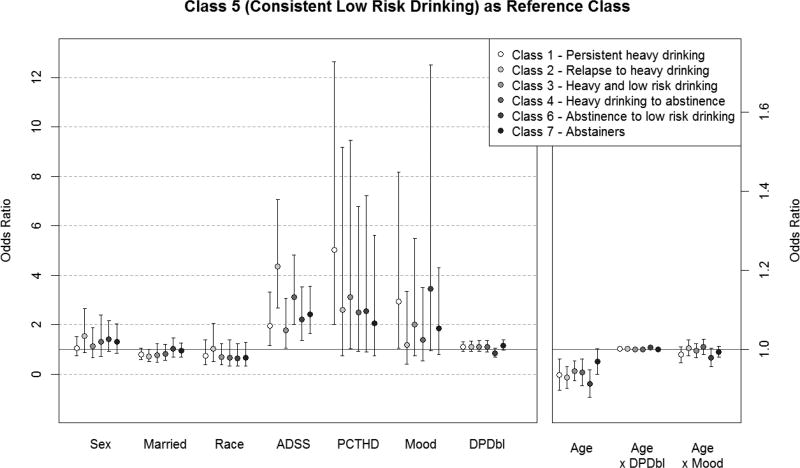

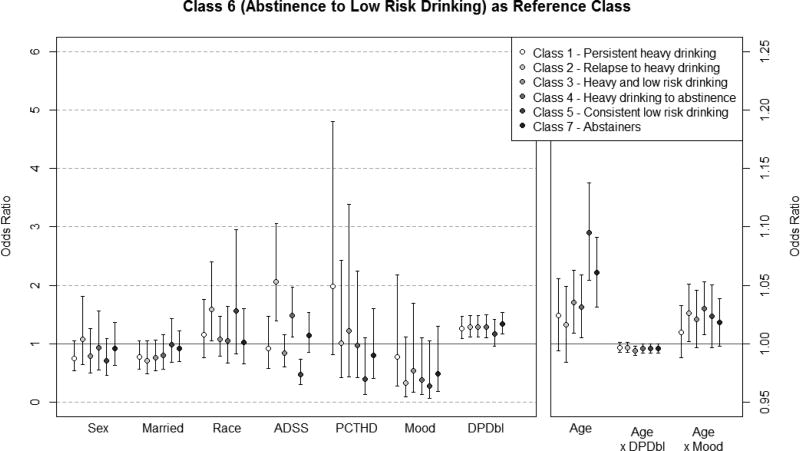

Descriptive data, shown in Table 3, provide the demographics (sex, marital status, and race) and baseline characteristics by latent class (see Supplemental Figure 1). Inferential analyses using multinomial logistic regression were conducted to examine the association between each of the baseline predictors and the odds of expected classification in a given class as compared to each other class. For the purposes of the current study we were particularly interested in the probability of the low risk drinking classes versus all other classes, specifically we focused on Class 5 “consistent low risk drinking” (Figure 1) and Class 6 “abstinence-to-low risk drinking” (Figure 2) as the reference classes. Supplemental Figures 2–6, provide the associations between predictors and odds of expected class membership with all other classes as reference classes.

Table 3.

Frequencies and Means for Demographic and Baseline Characteristics by Latent Classes

| Class 1: Persistent Heavy Drinkers |

Class 2: Relapse to Heavy Drinking |

Class 3: Heavy & Low Risk Drinking |

Class 4: Heavy Drinking & Abstinence |

Class 5: Consistent Low Risk Drinking |

Class 6: Abstinence & Low Risk Drinking |

Class 7: Abstainers |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex % Male | 70.1 ab | 79.3 c | 66.1 b | 72.7 abc | 64.1 b | 71.0 abc | 75.9 ac |

| Race % White | 86.6 ab | 83.4 abcd | 78.4 bd | 81.8 abcd | 89.8 a | 77.9 cd | 79.6 cd |

| Marital status % Married | 37.3 ab | 32.7 b | 41.5 abcde | 39.3 abe | 53.5 d | 48.1 cde | 43.0 ace |

| Age | 40.8 ab | 39.6 a | 42.3 bc | 41.0 bc | 46.5 d | 41.1 a | 43.0 c |

| Proportion of heavy drinkers in social network | 0.17 a | 0.16 ab | 0.12 b | 0.15 ab | 0.10 c | 0.12 bc | 0.14 b |

| Drinks per day in week prior to baseline | 9.6 a | 12.5 b | 5.6 c | 9.0 a | 5.2 c | 5.9 c | 10.9 d |

| Alcohol dependence severity score | 0.07 a | 0.36 b | −0.20 c | 0.15 a | −0.49 d | −0.33 cd | 0.05 a |

| Negative mood symptoms score | 0.75 a | 0.27 b | 0.14 bc | 0.61 a | 0.07 bc | −0.05 c | 0.06 c |

Note. Means in each row that share a subscript are not significantly different from each other. Statistical tests were based on χ2 tests for binary variables and Tukey post hoc comparisons for continuous variables.

Figure 1. Patient Characteristics and Expected Classification in Classes 1–4 and 6–7 as Compared to Class 5 (Reference Class).

Figure note. The y-axis is the odds ratio and the baseline covariates are represented by the x-axis. The left y-axis provides the odds ratios on a scale of 0 to 12 for the following covariates: sex, married, race, ADSS, PCTHD, mood, and DPDbl. The right y-axis provides the odds ratios on a scale of less than 0 to 2 for the age covariate and age x DPDbl and age x mood interactions. 95% confidence intervals are represented by the error bars. If the error bar crosses the 1.0 reference line then the odds ratio is not significant (p≥0.05) and the characteristic does not significantly predict expected odds of membership in a given latent class, as compared to the reference class. If the error bar is above the 1.0 reference line then the odds ratio is significant (p<0.05) and the characteristic predicts a significantly higher likelihood of expected membership in a given latent class, as compared to the reference class. If the error bar is below the 1.0 reference line then the odds ratio is significant (p<0.05) and the baseline characteristic predicts a significantly lower likelihood of expected membership in a given latent class, as compared to the reference class.

Sex coded male = 1; Married coded married = 1; Race coded non-Hispanic White = 1; ADSS = alcohol dependence severity score; PCTHD = percent heavy drinkers in the social network; Mood = negative mood symptoms score; DPDbl = baseline drinks per week.

Figure 2. Patient Characteristics and Expected Classification in Classes 1–5 and 7 as Compared to Class 6 (Reference Class).

Figure note. The y-axis is the odds ratio and the baseline covariates are represented by the x-axis. The left y-axis provides the odds ratios on a scale of 0 to 12 for the following covariates: sex, married, race, ADSS, PCTHD, mood, and DPDbl. The right y-axis provides the odds ratios on a scale of less than 0 to 2 for the age covariate and age x DPDbl and age x mood interactions. 95% confidence intervals are represented by the error bars. If the error bar crosses the 1.0 reference line then the odds ratio is not significant (p≥0.05) and the characteristic does not significantly predict expected odds of membership in a given latent class, as compared to the reference class. If the error bar is above the 1.0 reference line then the odds ratio is significant (p<0.05) and the characteristic predicts a significantly higher likelihood of expected membership in a given latent class, as compared to the reference class. If the error bar is below the 1.0 reference line then the odds ratio is significant (p<0.05) and the baseline characteristic predicts a significantly lower likelihood of expected membership in a given latent class, as compared to the reference class.

Sex coded male = 1; Married coded married = 1; Race coded non-Hispanic White = 1; ADSS = alcohol dependence severity score; PCTHD = percent heavy drinkers in the social network; Mood = negative mood symptoms score; DPDbl = baseline drinks per week.

Consistent Low Risk Drinking (Class 5) as Reference Class

In the analyses with Class 5 “consistent low risk drinking” as the reference class (see Figure 1), greater alcohol dependence severity was associated with a higher probability of membership in all other classes, as compared to Class 5. Greater percent of heavy drinkers in the social network and greater negative mood symptoms predicted higher probability of being in Class 1 “persistent heavy drinking” versus Class 5. Older age predicted a significant lower probability of expected membership in Class 1 “persistent heavy drinking” (OR=0.94, 95% CI: 0.90, 0.98), Class 2 “relapse-to-heavy drinking” (OR=0.93, 95% CI: 0.90, 0.96), Class 3 “mixed heavy and low risk drinking” (OR=0.95, 95% CI: 0.92, 0.97), Class 4 “heavy drinking-to-abstinence” (OR=0.94, 95% CI: 0.90, 0.98), and Class 6 “abstinence-to-low risk drinking” (OR=0.91, 95% CI: 0.88, 0.95), as compared to Class 5.

Abstinence-to-Low Risk Drinking (Class 6) as Reference Class

In the analyses with Class 6 “abstinence-to-low risk drinking” as the reference class (see Figure 2), greater baseline drinking was associated with a significantly higher likelihood of expected membership in Classes 1–4 and Class 7, as compared to Class 6. Being non-Hispanic White predicted greater likelihood of membership in Class 2 “relapse-to-heavy drinking,” as compared to Class 6. Older age predicted a significantly greater probability of expected membership in Class 3 “mixed heavy and low risk drinking” (OR=1.04, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.06), Class 4 “heavy drinking-to-abstinence” (OR=1.03, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.06), Class 5 “consistent low risk drinking” (OR=1.10, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.14), and Class 7 “abstainers” (OR=1.06, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.09), as compared to Class 6. Greater alcohol dependence severity was associated with a higher probability of membership in Class 2 “relapse-to-heavy drinking” and Class 4 “heavy drinking-to-abstinence,” as compared to Class 6.

There were two significant two-way interactions with Class 6 as the reference class. The age-by-baseline drinking interaction significantly predicted membership in Class 3 “mixed heavy and low risk drinking”, as compared to Class 6. Simple slopes analysis at one standard deviation below and above the average age indicated that baseline drinking did not predict membership in Class 3 “mixed heavy and low risk drinking” among younger individuals (OR=1.01, 95% CI: 0.92, 1.11), but greater baseline drinking significantly predicted a lower probability of membership in Class 3 among older individuals (OR=0.88, 95% CI: 0.80, 0.96). There was also a significant interaction between age and negative mood in predicting membership in Class 4 “heavy drinking-to-abstinence.” Greater negative mood symptoms predicted a greater likelihood of membership in Class 4 among older individuals (OR=2.54, 95% CI: 1.60, 4.05) but did not predict class membership among younger individuals (OR=1.30, 95% CI: 0.85, 1.99).

Discussion

Previous research has examined the association between patient characteristics and low risk (i.e., controlled) drinking outcomes among individuals with alcohol use disorder[11, 12, 14], but most prior research has been limited by small sample sizes and has primarily focused on predicting low risk drinking outcomes following treatment. The current study tested baseline predictors of drinking patterns during treatment among 3,589 patients across three alcohol clinical trials. Of seven distinct patterns of drinking, we identified two low risk drinking patterns: (1) consistent low risk drinking throughout treatment and (2) abstinence early in treatment and a higher probability of low risk drinking during later weeks of treatment. Combined across both patterns, we found over 17% of the sample achieved low risk drinking, in the absence of heavy drinking, by the end of treatment. One of the primary strengths of the current study was the use of an analytic approach that allowed for some deviations from abstinence and low risk drinking in identifying overall patterns of drinking during treatment, whereas many prior studies have defined low risk drinking by never exceeding low risk drinking limits[8, 9, 10, 12]. This is important given that clinicians are often interested in overall drinking patterns, rather than single instances of exceeding a low risk drinking threshold.

Alcohol dependence severity and drinks per day in the week prior to baseline significantly predicted low risk drinking patterns, with greater alcohol dependence severity and greater baseline drinking associated with heavier drinking and abstinence patterns. Prior research has also found that individuals who are higher in alcohol dependence severity may be more likely to achieve abstinence goals[44–46] and individuals lower in dependence severity are more likely to achieve moderate and low risk drinking[11, 21]. Greater negative mood symptoms and having more heavy drinkers in the social network were also significant predictors of heavier drinking patterns during treatment and individuals with these characteristics may have greater difficulty maintaining a low risk drinking trajectory during treatment. Prior studies[6, 47, 48] have found that drinking during treatment is strongly associated with post-treatment functioning, even up to 3 years post-treatment[48].

Findings for age were more complex. Older age predicted a greater likelihood of consistent low risk drinking, but younger age predicted a greater likelihood of abstinence to low risk drinking. There were significant interactions between age, baseline drinking, and negative mood symptoms. Among older individuals, greater baseline drinking was associated with a higher probability of low risk drinking than mixed heavy and low risk drinking. Thus, for individuals with greater baseline drinking, older age may improve the likelihood of low risk drinking. Older individuals with greater negative mood symptoms were more likely to transition from heavy drinking to abstinence and were less likely to follow a low risk drinking pattern. Future research, perhaps with an older adult sample, could further investigate whether more negative mood symptoms interfere with low risk drinking and whether greater baseline drinking might actually portend a higher likelihood of low risk drinking.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study had numerous limitations. First, we were limited to the available data across the three alcohol clinical trials, and due to this limitation, we did not include many other factors that have previously been identified as predictors of controlled drinking, such as the individual’s drinking goal[46, 49] and family history of alcohol dependence[11]. Preliminary model testing with the available family history data (COMBINE and MATCH) and available drinking goal data (COMBINE and UKATT) did not suggest these were robust predictors of low risk drinking. Preliminary models also tested education, income, and employment status, but none of these emerged as significant predictors. Finally, COMBINE, MATCH, and UKATT all excluded individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders and COMBINE excluded individuals who could not maintain abstinence for 4 days prior to starting treatment, which may limit the generalizability of the present findings with respect to psychiatric symptoms predicting drinking during treatment and the severity of AUD in the sample (particularly in the COMBINE participants). Additionally, the treatment period for COMBINE was 16 weeks, however only the first 12 weeks of data were analyzed in the current paper. Recent work examining the COMBINE data has indicated that most changes in drinking occur during the first 2–3 months of treatment[50], which is reflected in the time-period analyzed in the current study. Nonetheless, future research examining the full 16 week treatment period could further help elucidate predictors of drinking patterns during treatment in the COMBINE study.

An additional limitation is that the treatments examined in Project MATCH and COMBINE primarily focused on skills to maintain abstinence and, with the exception of the UKATT study, patients did not receive training in skills to moderate alcohol consumption. Our findings should be interpreted in that light. Future research could extend the current study by examining patients in programs that allow moderate drinking goals and impart skills to achieve moderate drinking. Future research could also extend the current study by examining treatment factors that might modify drinking trajectories, including treatment attendance and engagement[51, 52] and therapeutic alliance[53–55].

In conclusion, the current study provides some guidance for clinicians who are working with patients who are interested in low risk drinking. Lower alcohol dependence severity, less baseline drinking, fewer heavy drinkers in the social network, and lower negative mood symptoms appear to be the most robust predictors of low risk drinking patterns. Individuals with these characteristics may be good candidates for low risk drinking goals in alcohol treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by grants funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [R01 AA022328 (Witkiewitz, PI); K01 AA023233 (Pearson, PI); 2K05 AA016928 (Maisto, PI); T32 AA018108 (McCrady, PI); T32AA007455 (Larimer, PI); F31AA024959 (Kirouac, PI)]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of NIH.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests: None.

Contributor Information

Katie Witkiewitz, University of New Mexico.

Matthew R. Pearson, University of New Mexico.

Kevin A. Hallgren, University of Washington.

Stephen A. Maisto, Syracuse University.

Corey R. Roos, University of New Mexico.

Megan Kirouac, University of New Mexico.

Adam D. Wilson, University of New Mexico.

Kevin A. Montes, University of New Mexico.

Nick Heather, Northumbria University.

References

- 1.Miller WR. Form 90: A structured assessment interview for drinking and related behaviors. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Probst C, Manthey J, Martinez A, Rehm J. Alcohol use disorder severity and reported reasons not to seek treatment: a cross-sectional study in European primary care practices. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2015;10:32. doi: 10.1186/s13011-015-0028-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kline-Simon AH, Falk DE, Litten RZ, Mertens JR, Fertig J, Ryan M, et al. Posttreatment low-risk drinking as a predictor of future drinking and problem outcomes among individuals with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;(37 Suppl 1):E373–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witkiewitz K, Roos CR, Pearson MR, Hallgren KA, Maisto SA, Kirouac M, et al. How much is too much? Patterns of drinking during alcohol treatment and associations with post-treatment outcomes across three alcohol clinical trials. J Stud Acohol Drugs. 2017;78(1):59–69. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aldridge A, Zarkin GA, Dowd W, Bray JW. The relationship between end of treatment alcohol use and subsequent health care costs: Do heavy drinking days predict higher health care costs? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(5):1122–8. doi: 10.1111/acer.13054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witkiewitz K. “Success” following alcohol treatment: moving beyond abstinence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013 Jan;(37 Suppl 1):E9–13. doi: 10.1111/acer.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falk DE, Wang XQ, Liu L, Fertig J, Mattson M, Ryan M, et al. Percentage of subjects with no heavy drinking days: evaluation as an efficacy endpoint for alcohol clinical trials. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(12):2022–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Food and Drug Administration. Alcoholism: Developing drugs for treatment. Silver Spring; MD: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg H. Prediction of controlled drinking by alcoholics and problem drinkers. Psychol Bull. 1993;113(1):129–39. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orford J, Keddie A. Abstinence or controlled drinking in clinical practice: indications at initial assessment. Addict Behav. 1986;11(2):71–86. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ojehagen A, Berglund M, Moberg AL. A 6-year follow-up of alcoholics after long-term outpatient treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18(3):720–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elal-Lawrence G, Slade PD, Dewey ME. Predictors of outcome type in treated problem drinkers. J Stud Alcohol. 1986;47(1):41–7. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1986.47.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller WR, Leckman AL, Delaney HD, Tinkcom M. Long-term follow-up of behavioral self-control training. J Stud Alcohol. 1992;53(3):249–61. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards G, Brown D, Oppenheimer E, Sheehan M, Taylor C, Duckitt A. Long term outcome for patients with drinking problems: the search for predictors. Br J Addict. 1988;83(8):917–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchez-Craig M, Annis HM, Bornet a R, MacDonald KR. Random assignment to abstinence and controlled drinking: evaluation of a cognitive-behavioral program for problem drinkers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52(3):390–403. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foy DW, Nunn LB, Rychtarik RG. Broad-spectrum behavioral treatment for chronic alcoholics: effects of training controlled drinking skills. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52(2):218–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordström G, Berglund M. A prospective study of successful long-term adjustment in alcohol dependence: social drinking versus abstinence. J Stud Alcohol. 1987;48(2):95–103. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finney JW, Moos RH. Characteristics and prognoses of alcoholics who become moderate drinkers and abstainers after treatment. J Stud Alcohol. 1981;42(1):94–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1981.42.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuerbis A, Morgenstern J, Hail L. Predictors of moderated drinking in a primarily alcohol-dependent sample of men who have sex with men. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26(3):484–95. doi: 10.1037/a0026713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gueorguieva R, Wu R, Donovan D, Rounsaville BJ, Couper D, Krystal JH, et al. Baseline trajectories of heavy drinking and their effects on postrandomization drinking in the COMBINE Study: empirically derived predictors of drinking outcomes during treatment. Alcohol. 2012;46(2):121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCutcheon VV, Kramer JR, Edenberg HJ, Nurnberger JI, Kuperman S, Schuckit MA, et al. Social Contexts of Remission from DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder in a High-Risk Sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(7):2015–23. doi: 10.1111/acer.12434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worley MJ, Witkiewitz K, Brown SA, Kivlahan DR, Longabaugh R. Social network moderators of naltrexone and behavioral treatment effects on heavy drinking in the COMBINE study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(1):93–100. doi: 10.1111/acer.12605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trim RS, Schuckit MA, Smith TL. Predictors of Initial and Sustained Remission from Alcohol Use Disorders: Findings from the 30-Year Follow-Up of the San Diego Prospective Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(8):1424–31. doi: 10.1111/acer.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.COMBINE Study Group. Testing combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions in alcohol dependence: rationale and methods. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(7):1107–22. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200307000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Project MATCH Research Group. Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58(1):7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.UKATT Research Team. United Kingdom Alcohol Treatment Trial (UKATT): Hypotheses, design and methods. Alcohol Alcohol. 2001;36(1):11–21. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clifford PR, Longabaugh R. Manual for the Administration of the Important People and Activities Instrument. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Witkiewitz K, Hallgren KA, O’Sickey AJ, Roos CR, Maisto SA. Reproducibility and differential item functioning of the alcohol dependence syndrome construct across four alcohol treatment studies: An integrative data analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;158:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skinner HA, Horn JL. Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS) user’s guide. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. 3rd ed., rev.; DSM-III-R. revised. [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. 4th ed.; DSM-IV) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raistrick D, Bradshaw J, Tober G, Weiner J, Allison J, Healey C. Development of the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire (LDQ): a questionnaire to measure alcohol and opiate dependence in the context of a treatment evaluation package. Addiction. 1994;89(5):563–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derogatis LR. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychol Med A J Res Psychiatry Allied Sci. 1983;13(3):595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldberg D. Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: Nelson; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences. New York, NY: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus users guide (Version 7) Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwarz GE. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6:461–4. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Model. 2007;14(4):535–69. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muthén BO, Satorra A. Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociol Methodol. 1995;25:267–316. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heather N, Adamson SJ, Raistrick D, Slegg GP. UKATT Research Team. Initial preference for drinking goal in the treatment of alcohol problems: I. Baseline differences between abstinence and non-abstinence groups. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45(2):128–35. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adamson SJ, Heather N, Morton V, Raistrick D. UKATT Research Team. Initial preference for drinking goal in the treatment of alcohol problems: II. Treatment outcomes. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45(2):136–42. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ojehagen A, Berglund M. Changes of drinking goals in a two-year out-patient alcoholic treatment program. Addict Behav. 1989;14(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gueorguieva R, Wu R, Fucito LM, O’Malley SS. Predictors of Abstinence From Heavy Drinking During Follow-Up in COMBINE. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76(6):935–41. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maisto SA, McKay JR, O’Farrell TJ. Twelve-month abstinence from alcohol and long-term drinking and marital outcomes in men with severe alcohol problems. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59(5):591–8. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hodgins DC, Leigh G, Milne R, Gerrish R. Drinking goal selection in behavioral self-management treatment of chronic alcoholics. Addict Behav. 1997;22(2):247–55. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Witkiewitz K, Wilson AD, Pearson MR, Hallgren KA, Falk DE, Litten RZ, et al. Temporal Stability of Heavy Drinking Days and Drinking Reductions among Heavy Drinkers in the COMBINE Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017 doi: 10.1111/acer.13371. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirouac M, Witkiewitz K, Donovan DM. Client Evaluation of Treatment for Alcohol Use Disorder in COMBINE. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;67:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dale V, Coulton S, Godfrey C, Copello A, Hodgson R, Heather N, et al. Exploring Treatment Attendance and its Relationship to Outcome in a Randomized Controlled Trial of Treatment for Alcohol Problems: Secondary Analysis of the UK Alcohol Treatment Trial (UKATT) Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(5):592–9. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hartzler B, Witkiewitz K, Villarroel N, Donovan D. Self-efficacy change as a mediator of associations between therapeutic bond and one-year outcomes in treatments for alcohol dependence. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(2):269–78. doi: 10.1037/a0022869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maisto SA, Roos CR, O’Sickey AJ, Kirouac M, Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, et al. The indirect effect of the therapeutic alliance and alcohol abstinence self-efficacy on alcohol use and alcohol-related problems in Project MATCH. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(3):504–13. doi: 10.1111/acer.12649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cook S, Heather N, McCambridge J. United Kingdom Alcohol Treatment Trial Research Team. The role of the working alliance in treatment for alcohol problems. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29(2):371–81. doi: 10.1037/adb0000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.