Abstract

Background

Anemia is responsible for 20% of maternal mortality worldwide, and it is associated with premature birth, low birth weight, and infant mortality. In Ethiopia, about 22% of pregnant women are anemic. However, literatures are limited, therefore, this study aimed to investigate the prevalence and associated factors of anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care (ANC) in Asossa Zone Public Health Institutions, northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

A facility based cross-sectional study was conducted from February to March 2016. Data were collected by interviewer administered, pretested and structured questionnaires. A multi-stage sampling technique was used to select 762 pregnant women. The hemoglobin level was determined by taking 5 ml of venous blood using Sahli’s method. A multivariate binary logistic regression model was fitted to identify factors associated with anemia. Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) was computed to show the strength of association and statistical significance was determined at a P-value of <0.05.

Results

The prevalence of anemia was 31.8% [95% CI: 28.9, 35.5]. In the adjusted analysis, maternal age of 30–34 years [AOR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.14, 0.86], household size of ≥6 [AOR = 4.27, 95% CI: 1.58, 11.45], dietary diversity [AOR = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.38, 0.93], no meat consumption [AOR = 1.80, 95% CI: 1.11, 2.91], not drinking soft beverages [AOR =1.96, 95% CI: 1.19, 3.23], undernutrition [AOR = 7.38, 95% CI: 4.22, 12.91], not consuming fruits [AOR = 3.29, 95% CI: 1.59, 6.82], inter-pregnancy interval of ≥2 years [AOR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.34, 0.99], and third trimester of pregnancy [AOR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.20, 0.57] were significantly associated with anemia.

Conclusions

The prevalence of prenatal anemia is high in the Asossa Zone; suggesting a moderate public health concern. Socio-demographic and dietary intake characteristics were significantly associated with anemia. Therefore, improving dietary diversity and animal food consumption are the key to reduce the high burden of anemia. It is also important to strengthen interventions aiming to reduce closed birth interval and teenage pregnancy.

Keywords: Pregnant women, Anemia, Determinants, Ethiopia

Background

Anemia is a nutritional disorder resulted from a hemoglobin level below the established normal reference values. It exists as mild to moderate public health problem in developed and developing countries [1]. Despite anemia affects all segments of the population, pregnant women are the most vulnerable groups because of their unique physiological state. Anemia is correlated with adverse health consequences and affects the socio-economic development of the country [2, 3]. Worldwide, anemia is an important preventable cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality [4]. It is causes 20% of maternal death and associated with premature birth, low birth weight, and infant mortality. Moreover, it impairs the growth and learning ability of children, resistance to infections, and physical work capacity and productivity of adults [5–7].

Globally, about 38.2% of pregnant mothers are anemic, while almost two-third are anemic in developing countries. In Africa, prenatal anemia was detected in 48.7% of mothers [8]. Ethiopian has been undertaking different measures (iron-folate supplementation, malaria treatment and control strategies, and deworming) to control anemia [7]. However, the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey report showed that, still 22% of pregnant mothers are suffering from anemia [9].

The former researches in different developing countries, including Ethiopia, illustrated that maternal anemia is multi-factorial. Accordingly, age, place of residence, marital status, employment status, household size, educational and wealth status are socio demographic and economic determinants of anemia. Chronic energy deficiency, meal frequency, dietary diversity, gravidity, parity, inter-pregnancy interval, gestational age and history of infectious disease, malarial attack and intestinal parasitic infestation are also significantly associated with anemia in pregnant mothers [8–24].

Obviously, monitoring of health problems and its determinants is essential for developing effective interventions [19]. Particularly, it has a special importance for countries, like Ethiopia where the burden of health and nutritional problems, including amenia is high [10]. However, there is limited scientific evidence, especially in Benishangul Gumz Regional State, the study area. Thus, this study aimed to assess the prevalence and associated factors of anemia among pregnant mothers attending ANC clinic in public health institutions of Asossa Zone, northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design and settings

A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted from February to March 2016 in Asosa Zone which is found in Benishangul Gumuz Regional State, northwest Ethiopia. The zone lies at 580–1668 m above sea level and 661 km far from the capital of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. According to the recent (2015/2016) Regional Finance and Economic Development Office projection, total population of the zone was estimated at 377852, in which 12,885 were pregnant women. Furthermore, the health coverage was 86%, and 11 public health centers and one general hospital were providing health service to the community during the data collection time [25].

Study population and sampling procedure

All pregnant mothers attending ANC clinic for their regular follow-up in Asossa Zone Public Health Institutions during the study period were eligible for the study. A single population proportion formula was used to estimate sample size. Assumptions, including prevalence of anemia in Benishangul Gumuz Regional State as 28% [12], 95% confidence level, 4% margin of error, 5% non-response rate, and a design effect of 1.5 were considered to obtain sample size of 762.

A multi-stage sampling technique was employed to select the study participants. The public health facilities were stratified into health centers and hospital, and a lottery method was used to choose 5 health facilities (4 health centers and 1 general hospital) from the total. Quantity of pregnant mothers attended (1676) ANC in the previous year (2015) in the selected health institutions was taken from the registration log book to estimate sampling fraction. Total samples included in each health facility were proportionate to population size and then systematic sampling technique was employed using the calculated sampling interval (kth = 1676/762 = 2.2) to select the study participants.

Data collection instrument and procedures

Pretested interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. The English version questionnaire was translated into Amharic language (native language of the study area) and then back translated to English by language and public health experts. A total of 13 data collectors (6 nurses and 5 laboratory technicians) and 2 public health officers as supervisor were recruited for the study.

A 5 ml of venous blood was collected into 2/3 of micro-hematocrit tube with anti-coagulant and centrifuged for 5 min. Hemoglobin estimation was done by comparative Sahli’s method and the result was expressed in g/dl. Hemoglobin value was adjusted by considering altitude of the study area [26]. Finally, severity of anemia was defined as non-anemic (hemoglobin level ≥ 11.0 g/dl), mild anemia (hemoglobin level of 10.0–10.9 g /dl), moderate anemia (hemoglobin level of 7.0–9.9 g/dl), and severe anemia (hemoglobin level of <7 g/dl) [27].

Nutritional status of participants was assessed by measuring the Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) using the measuring tape. Accordingly, undernutrition was ascertained when the MUAC measurement was ≤21 cm [28].

Dietary Diversity Score (DDS) of pregnant women was calculated by using a 24–hour recall method. An open recall method was employed to gather information about the foods and drinks consumed by the study participants. Accordingly, woman was requested to list what she ate in the past 24 h prior to the date of interview. The score was computed based on 9 food groups which aimed to reflect the micronutrient adequacy of the diet. Finally, mother’s dietary intake was categorized into poor, medium and high dietary diversity score if she consumed ≤3 food groups, 4–5 food groups and ≥6 food groups, respectively [29].

Livestock ownership, selected household assets, size of agricultural land, and the quantity of crop production were the variables used in determining the household wealth status. A principal components analysis was used and the factor scores were summarized into terciles (poor, medium and rich) [30].

Three days of training was given to data collectors and supervisors. The training mainly focused on the purpose of the study, techniques of interview, and important ethical issues of the research project. Pretest was done on 5% of the total sample out of the study area, Abrhamo Health Center. During pre-test, the applicability of data collection procedures and tools were evaluated. Regularly all questioners were checked for completeness, clarity and consistency by the supervisors and investigators.

Data processing and analysis

Data were entered into EPI INFO version 7 and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and proportions were used to summarize variables. A binary logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with anemia. Variables with a P-value of <0.2 in the bivariate analysis were exported to the multivariate analysis to control the possible effect of confounders. The Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence level was estimated to show the strength of association, and a P-Value of <0.05 was used to declare the statistical significance in the multivariate analysis.

Results

Socio-demographic and economic characteristics

A total of 761 pregnant mothers were participated in this study giving a response rate of 99.9%. The median age was 25.0 year with an inter-quartile range of 7.0 year. Three-fourth (76.5%) of the study participants were urban inhabitants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio–demographic and economic characteristics of pregnant mothers attending antenatal care clinic in Asossa Zone Public Health Institutions, northwest Ethiopia, 2016 (n = 761)

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | ||

| < 20 | 76 | 10.0 |

| 20–24 | 247 | 32.5 |

| 25–29 | 264 | 34.7 |

| 30–34 | 126 | 16.6 |

| ≥ 35 | 48 | 6.3 |

| Religion | ||

| Muslims | 368 | 48.4 |

| Orthodox | 301 | 39.6 |

| Protestant | 92 | 12.0 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 582 | 76.5 |

| Rural | 179 | 23.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Berta | 215 | 28.3 |

| Shinasha | 56 | 7.4 |

| Amhara | 256 | 33.6 |

| Oromo | 164 | 21.6 |

| Tigre | 43 | 5.7 |

| Others | 27 | 3.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 727 | 95.5 |

| Unmarrieda | 34 | 4.5 |

| Educational status | ||

| No formal education | 333 | 43.8 |

| Primary education | 107 | 14.1 |

| Secondary education | 123 | 16.2 |

| Certificate and above | 198 | 26.0 |

| Employment status | ||

| House wife | 503 | 66.1 |

| Government employee | 194 | 25.5 |

| Self employed | 46 | 6.0 |

| Others | 18 | 2.4 |

| Family size | ||

| ≤ 2 | 252 | 33.1 |

| 3–5 | 398 | 52.3 |

| ≥ 6 | 111 | 14.6 |

| Household wealth status | ||

| Poor | 208 | 27.4 |

| Medium | 319 | 41.9 |

| Rich | 234 | 30.7 |

asingle, divorced and widowed

Prevalence of anemia, dietary habit, and health related characteristics

More than half (56.8%) of the study participants had 3 meals per a day. About 62.2% of study subjects ate meat at least once per week. One-quarter (25.4%) of women had high DDS and about 85.5% were well nourished (Table 2). Half (45.9%) of the pregnant mothers were found at third trimester of pregnancy. Majority of (77.1%) the study participants had history of closed inter-pregnancy interval (less than two years) and 13.4% had history of repeated malaria infection (Table 3).

Table 2.

Dietary pattern and nutritional status related characteristics of pregnant mothers attending antenatal care clinic in Asossa Zone Public Health Institutions, northwest Ethiopia, 2016 (n = 761)

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Meal frequency per day | ||

| ≥ 4 times | 237 | 31.1 |

| 3 times | 432 | 56.8 |

| ≤ 2 times | 92 | 12.1 |

| Frequency of meat consumption per week | ||

| ≥ Once per week | 473 | 62.2 |

| None | 288 | 37.8 |

| Tea/coffee consumption per day | ||

| Yes | 726 | 95.4 |

| No | 35 | 4.6 |

| Consumption of soft drinks per week | ||

| ≥ Once per week | 544 | 71.5 |

| Never | 217 | 28.5 |

| Fruit consumption per week | ||

| Greater than twice per week | 183 | 24.0 |

| Twice per week | 260 | 34.2 |

| Once per week | 196 | 25.8 |

| Once per month | 122 | 16.0 |

| Egg consumption per week | ||

| Every day | 23 | 3.0 |

| Once per week | 230 | 30.2 |

| More than or equal to twice per week | 137 | 18.0 |

| Once per month | 154 | 20.2 |

| None | 217 | 28.5 |

| Milk and milk products consumption per week | ||

| More than once per day | 25 | 3.3 |

| Once per day | 75 | 9.9 |

| Once per week | 320 | 42.0 |

| None | 341 | 44.8 |

| Staple food of the family | ||

| Injera | 621 | 81.6 |

| Porridge | 140 | 18.4 |

| Dietary Diversity Scores | ||

| Poor | 191 | 25.1 |

| Medium | 377 | 49.5 |

| High | 193 | 25.4 |

| MUAC Measurement | ||

| ≤ 21 cm | 110 | 14.5 |

| ≥ 22 cm | 651 | 85.5 |

Table 3.

Health care related characteristics of pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic in Asossa Zone Public Health Institutions, northwest Ethiopia, 2016 (n = 761)

| Variables | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gravidity of the mother | ||

| One | 255 | 33.5 |

| Two | 212 | 27.9 |

| Three and above | 294 | 38.6 |

| Parity of the mother | ||

| Null–parous | 260 | 34.2 |

| Para–One and Two | 212 | 27.9 |

| Para–Three and above | 289 | 38.0 |

| Gestational age | ||

| First trimester | 154 | 20.2 |

| Second trimester | 258 | 33.9 |

| Third trimester | 349 | 45.9 |

| Inter pregnancy interval in years | ||

| < 2 | 587 | 77.1 |

| ≥ 2 | 174 | 22.9 |

| History of abortion | ||

| Yes | 48 | 6.3 |

| No | 713 | 93.7 |

| History of repeated malaria infection | ||

| Yes | 102 | 13.4 |

| No | 659 | 86.6 |

| History of chronic illness | ||

| Yes | 19 | 2.5 |

| No | 742 | 97.5 |

| Intestinal parasite infestation in past one week | ||

| Yes | 7 | 1.0 |

| No | 754 | 99.0 |

| Iron- folate supplementation | ||

| Yes | 647 | 85.0 |

| No | 114 | 15.0 |

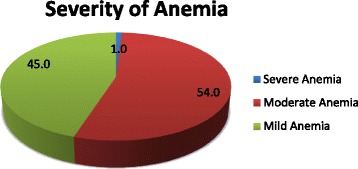

About 31.8% [95% CI: 28.9, 35.5] of pregnant mothers were anemic in the study area, of which 54.0% were moderately anemic. After adjustments were done for altitude, the median hemoglobin level was 11.80 g/dl and the Inter-Quartile Range was 2.0 g/dl (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Severity of anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Asossa Zone Public Health Institutions, northwest Ethiopia, 2016 (n = 761)

Factors associated with anemia

In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, age of the mother, household size, meat, soft drink and fruit consumption, DDS, nutritional status, gestational age and inter-pregnancy interval were independently and significantly associated with anemia.

In this study, the odds of developing anemia were 4.27 higher among mother who belonged to a household size of ≥6 as compared to mothers living in a household size of ≤2 [AOR = 4.27, 95 % CI: 1.58, 11.45]. The likelihood of having anemia was 80% higher among mothers who did not eat meat in the past 1-week (prior to the date of survey) compared to those who ate at least once per week [AOR = 1.80, 95 % CI: 1.11, 2.91].

The odds of anemia were 66% less in mothers aged 25–29 years when compared to those aged <20 years [AOR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.14, 0.86]. Also, the lesser odds of anemia were detected in mothers who had DDS of 4–5 [AOR = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.38, 0.93] and inter pregnancy interval of ≥2 years [AOR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.34, 0.99]. Similarly, the odds of having anemia were 67% less among mothers found in the third trimester of pregnancy compared to those found in the first trimester of pregnancy [AOR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.20, 0.57].

Soft drink consumption was also significantly associated with anemia. The odds of developing anemia were near to two times higher among mothers without history of weekly soft drink consumption compared to their counterparts [AOR =1.96, 95% CI: 1.19, 3.23]. Those pregnant mothers who did not consume fruit at least once per week were found at higher odds of developing anemia [AOR = 3.29, 95% CI: 1.59, 6.82]. Finally, the likelihood of anemia was 7.38 times higher in undernourished mothers (MUAC ≤21 cm) compared to well-nourished ones [AOR = 7.38, 95% CI: 4.22,12.91] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with anemia among pregnant mothers attending antenatal care clinic in Asossa Zone Public Health Institutions, northwest Ethiopia, 2016 (n = 761)

| Variables | Anemia | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (#) | No (#) | |||

| Mother age in years | ||||

| < 20 | 30 | 46 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 20–24 | 72 | 175 | 0.63 (0.37,1.08) | 0.63 (0.31,1.27) |

| 25–29 | 73 | 191 | 0.59 (0.344, 0.99) | 0.39 (0.18, 0.85)* |

| 30–34 | 43 | 83 | 0.79 (0.44, 1.43) | 0.34 (0.14, 0.86)* |

| ≥ 35 | 24 | 24 | 1.53 (0.74, 3.18) | 0.47(0.15,1.49) |

| Educational status | ||||

| No formal education | 139 | 194 | 2.50 (1.68, 3.74) | 0.67 (0.32, 1.40) |

| Primary education (1–8) | 33 | 74 | 1.56 (0.92, 2.65) | 0.93 (0.42, 2.03) |

| Secondary education (9–12) | 26 | 97 | 0.94 (0.54, 1.62) | 0.98 (0.46, 2.10) |

| Certificate and above | 44 | 154 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Employment status | ||||

| House wife | 179 | 324 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Government employee | 49 | 145 | 0.61 (0.42, 0.89) | 0.93 (0.48, 1.82) |

| Self employed | 12 | 34 | 0.64 (0.32, 1.23) | 1.63 (0.72, 3.73) |

| Others | 2 | 16 | 0.23 (0.05, 0.99) | 0.78 (0.16, 3.88) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Currently married | 226 | 501 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Currently unmarried | 16 | 18 | 1.97(0.99, 3.94) | 2.25 (0.94, 5.36) |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 158 | 424 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Rural | 84 | 95 | 2.37(1.68, 3.35) | 0.66 (0.33,1.30) |

| Household size | ||||

| ≤ 2 | 52 | 200 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 3–5 | 132 | 266 | 1.91(1.32, 2.76) | 2.30 (1.06, 4.99)* |

| ≥ 6 | 58 | 53 | 4.21(2.60, 6.81) | 4.27(1.58,11.50)** |

| Household Wealth status | ||||

| Poor | 80 | 128 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 81 | 238 | 0.55 (0.37, 0.79) | 0.77 (0.47,1.28) |

| Rich | 81 | 153 | 0.85 (0.58,1.25) | 1.44 (0.79, 2.62) |

| Meal frequency per day | ||||

| ≥ 4 Times | 53 | 184 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 3 Times | 144 | 288 | 1.74 (1.21, 2.50) | 0.68 (0.42, 1.11) |

| 2 Times | 47 | 45 | 3.32 (2.00, 5.54) | 0.94 (0.45, 1.96) |

| Meat consumption per week | ||||

| ≥ Once per week | 114 | 359 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| None | 128 | 160 | 2.52 (1.84, 3.45) | 1.80 (1.11, 2.91)* |

| Drinking of soft beverages per week | ||||

| ≥ Once per week | 133 | 411 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| None | 109 | 108 | 3.12 (2.24, 4.34) | 1.96 (1.19, 3.23)** |

| Fruit consumption per week | ||||

| > Twice per week | 30 | 153 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Twice per week | 57 | 203 | 1.43 (0.88, 2.34) | 1.01 (0.57, 1.79) |

| Once per week | 72 | 124 | 2.96 (1.82, 4.82) | 2.14 (1.20, 3.81)* |

| None | 83 | 39 | 10.9 (6.29,18.73) | 3.29 (1.59, 6.82)** |

| Egg consumption per week | ||||

| Every day | 3 | 20 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Once per week | 62 | 168 | 2.46 (0.71, 8.57) | 2.43 (0.63, 9.34) |

| ≥ Twice per week | 26 | 111 | 1.56 (0.43, 5.65) | 1.73 (0.43, 6.87) |

| Once per month | 77 | 77 | 6.67(1.90, 23.36) | 2.35 (0.58, 9.54) |

| Never | 74 | 143 | 3.45 (0.99,11.99) | 1.44 (0.36, 5.80) |

| Staple foods of the family | ||||

| Injera | 180 | 441 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Porridge | 62 | 78 | 1.95 (1.34, 2.84) | 1.33 (0.71, 2.49) |

| Dietary Diversity Score | ||||

| Poor | 89 | 102 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 94 | 283 | 0.38 (0.26, 0.55) | 0.58 (0.36, 0.93)* |

| High | 59 | 134 | 0.51(0.33, 0.77) | 1.03 (0.59, 1.80) |

| MUAC measurement | ||||

| ≤ 21 cm | 81 | 29 | 8.50 (5.37,13.47) | 7.38 (4.20, 12.90)*** |

| ≥ 22 cm | 161 | 490 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Gravidity of the mother | ||||

| Gravida–One | 58 | 197 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Gravida–Two | 70 | 142 | 1.67(1.11, 2.52) | 0.46 (0.07, 2.79) |

| Gravida–Three and above | 114 | 180 | 2.15 (1.48, 3.13) | 0.51(0.06, 4.54) |

| Parity of the mother | ||||

| Null–Parous | 57 | 203 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Para–One to Two | 72 | 140 | 1.83(1.22, 2.76) | 3.98 (0.61, 25.98) |

| Para–Three and above | 113 | 176 | 2.29 (1.57, 3.33) | 3.54 (0.37, 34.25) |

| Gestational age in (trimester) | ||||

| 1st Trimester | 70 | 84 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2nd Trimester | 88 | 170 | 0.62 (0.41, 0.94) | 0.61(0.36, 1.04) |

| 3rd Trimester | 84 | 265 | 0.38 (0.23, 0.57) | 0.33 (0.2, 0.57)*** |

| Birth interval in (years) | ||||

| < 2 | 201 | 386 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥ 2 | 41 | 133 | 0.59 (0.40, 0.87) | 0.59 (0.34, 0.99)* |

| History of repeated malaria infection | ||||

| Yes | 43 | 59 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 199 | 460 | 0.59 (0.39, 0.91) | 1.19 (0.68,2.09) |

Note:* P–value <0.05; ** P–value <0.01; *** P –value <0.00

Discussion

The burden of prenatal anemia is widely recognized as a major public health problem throughout the world, particularly in developing countries [8]. Because of blood volume expansion and increased iron demand of the fetus and the mother, hemoglobin level altered dramatically during the course of pregnancy [27].

This study noted that, the prevalence of anemia was 31.8% which confirmed the moderate public health significance of the problem. This finding was comparable with the former study from Ethiopia (27.8%) [13] and other developing countries, such as, Brazil (28.1%) [23] and Uganda (29.1%) [19]. The result was slightly higher than the previous local reports (16.6–22%) [9, 12, 31]. However, this report was lower than another study from Ethiopia (53.9%) [32] and Nigeria (54.5%) [33], Ghana (57.1%) [20], Burkina Faso (61%) [34] and Uganda (63.1%) [35]. The variation in the burden of anemia between the current and latter study settings could be related to disparities in occurrence of malaria and hookworm infestation. An increased magnitude of malaria [32, 34] and other febrile illness [33] and intestinal parasitic infestation [20, 32] are reported in the former studies. Febrile illnesses, including malaria, and parasitic infestation are correlated with reduced blood hemoglobin level [20, 32, 33]. Furthermore, higher utilization of iron-folate supplementation might explain the lower prevalence of anemia in the study area compared to what was reported in Nigeria [33] and Burkina Faso [34].

The result of multivariate analysis showed that, mothers age was significantly associated with anemia; the likelihood of developing anemia was lower among women aged 25–29 and 30–34 years compared to those aged <20 years. Similar findings were also reported by other studies, for instance Ethiopia [36], Uganda [18], Ghana [20], Thailand [37], and Turkey [38]. A former study also demonstrated that anemia is the common nutritional problem in teenage pregnancy [39]. Obviously, adolescence (10–19 years) is a state of rapid growth and development [40] which ultimately increases iron requirement (2.2 mg iron/day) by a fold compared to the preadolescent period (6–9 years) (0.7–0.9 mg iron/day) [41]. Unfortunately, if an adolescent girl becomes pregnant, the mother and fetus will compute for nutrients to support their rapid growth which in turn increases her vulnerability for anemia [42, 43].

Similarly, the higher likelihood of developing anemia was noted among mothers from the larger (≥6) family size compared to those from a smaller (≤2) family size. This finding was supported by the previous reports elsewhere; Ethiopia [12], Brazil [23] and India [44]. Most of the time large family size is associated with low socio-economic status of the household, for that reason little resources may be available to nourish the entire family members. Additionally, large family size is a strong indicator for closed birth spacing, which in turn affects maternal hemoglobin status [45].

Lack of meat consumption in the previous 1-week was significantly associated with higher odds prenatal anemia. This report was consistent with the reports from Ethiopia [15, 46], Pakistan [8], Turkey [38] and Vietnam [47]. Meat is a rich source of hem-iron which has better bioavailability compared to non-heme-iron, form of iron majorly obtained from plant based food groups [15, 48], On the other hand, hem-iron enhances absorbability of non-hem iron [49].

Furthermore, vitamin–C, a chief reducing equivalent, enhances absorption of iron in the gastrointestinal mucosa [50]. Given that, poor consumption of Vitamin-C rich food (fruits and vegetables) increases risk of developing anemia. In line to this fact, this study showed that the odds of anemia were increased among mothers who had no fruit intake in the previous week prior to date of data collection. Parallel findings were also reported from Pakistan [8] and Turkey [38].

This study also noted that the likelihood of having anemia was lower among mothers with diversified diet. Similar results were also reported from Ethiopia [31], Pakistan [8], and Turkey [38]. Dietary diversification, a proxy indicator of micronutrient adequacy of the diet, has special importance for the countries, like Ethiopia, in which the dietary habit of the population is relied on the monotonous cereal based food [51]. Cereals are energy dense, but poor in micronutrients.

This study illustrated that, drinking of soft beverages at least once per week was associated with reduced odds anemia. The result was in agreement with the earlier studies [35, 52]. Despite acidic beverages improve iron absorption, some of beverages containing tannin and caffeine are known to inhibit iron absorption [32]. Therefore, the relationship between soft drinks and anemia needs further investigation.

The odds developing anemia were higher among undernourished (MUAC ≤ 21 cm) mothers. The finding was supported by studies done in developing countries, such as Ethiopia [14], Kenya [53], India [54], and Nepal [55]. Pregnancy is the most nutritionally demanding time in a woman’s life, which increases the vulnerability of mothers for poor micronutrient reserve, including iron [51]. In addition, undernutrition impaired production of iron transport proteins and increased depletion of stored iron which in turn causes anemia [32, 56].

The risk of maternal nutritional depletion also increases with closed birth intervals and repeated pregnancies. Therefore, mothers need adequate time to restore nutritional reserve until the next pregnancy [57]. Mothers attain good nutritional status, including iron, when there is a gap of at least 2 years between consecutive pregnancies [58, 59]. In line to this fact, this study showed lower odds of developing anemia among women with greater than or equal to 2 years of inter-pregnancy interval compared to their counterparts. The finding was consistent with the previous studies in Ethiopia [60], Nepal [24] and India [61, 62].

The lower odds of anemia were also detected in the third trimester of pregnancy compared to those who were in the first trimester of pregnancy. However, it is not in line with the former local [13–15, 31, 63] and abroad reports of developing countries [8, 64]. Obviously, the risk of anemia increases with advancement of trimester of pregnancy [60]. Hemoglobin concentration starts declining during first trimester and reaches to lowest level during second trimester and rises again at the third trimester of pregnancy [28]. This might explain the lower odds of anemia in the third trimester of pregnancy in the current study. Moreover, most of the pregnant women starts to attend antenatal care in the second trimester of pregnancy and iron-folate supplementation is also given which in turn reduces mother’s nutritional depletion for iron.

This study investigated the burden of anaemia in the wider study area. However, some of the limitations ought to be taken into account. Cross–sectional nature of this study may not show temporal relationship between the dependent and independent variables. Moreover, ascertainment of repeated malaria infection was relied on the memory/information given by study participants, which might be subjected to recall bias.

Conclusions

The study revealed that, the burden of prenatal anemia is high and exists as moderate public health concern in Assosa Zone. In addition, prenatal anemia was majorly associated with socio-demographic and nutrition related factors. Therefore, improving dietary diversity, meat, energy, and fruit consumption are critical to mitigate maternal anemia. It is also important to strengthen measures aiming to address early pregnancy and closed birth interval.

Acknowledgments

First of all, the authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to study subjects for their willingness to participate in the study. The authors’ heartfelt thanks will also go to Benishangul Gumuz Regional State Health Department for the financial support.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Availability of data and materials

All the required data is available in the main paper.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Antenatal care

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- COR

Crude odds ratio

- DDS

Dietary Diversity Score

- MUAC

Mid-Upper Arm Circumference

- SD

Standard deviation

- SPSS

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

Authors’ contributions

Designed the experiments: AA. Approved the proposal with some revisions: HWY AT EG. Performed the experiments: AA HWY AT EG. Analyzed the data: AA HWY. Wrote the manuscript: HWY AT EG. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the University of Gondar. Ethical clearance was submitted to Benishangul Gumuz Regional Health Bureau Research and Technology Transfer Department. The letter of permission from Research and Technology Transfer Department was submitted to the Asossa Zonal Health Department and to the selected health institutions where the actual data collection was undertaken. The purpose of the study was explained and written informed consent was secured from each study participant. The right of a participant to withdraw from the study at any time, without any precondition was disclosed unequivocally. Moreover, the confidentiality of information obtained was guaranteed by all data collectors and investigators using code numbers rather than personal identifiers and by keeping the data locked. Those study participants with confirmed anemia were referred and linked to responsible health care professionals working in the selected health institutions.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Abera Abay, Email: abera.abay159@gmail.com.

Haile Woldie Yalew, Email: yalewhaile28@gmail.com.

Amare Tariku, Email: amaretariku15@yahoo.com.

Ejigu Gebeye, Email: ejigugebeye@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Turgeon ML. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. In: Clinical hematology: theory and procedures. 4th ed. p. 90, 113, 146- 148, 151,172–183, 113-14, 495-497.

- 2.WHO . The global prevalence of anemia in 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Awasthi S, Das R, Verma T, Vir S. Anemia and Undernutrition among preschool children in Uttar Pradesh, India. Indian Pediatr. 2003;40:985–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awan MM, Akbar MA, Khan MI. A study of anemia in pregnant women of railway colony, Multan Pakistan. J Med Res. 2004;43 No. 1:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karaoglu L, Pehlivan E, Egri M, Deprem C, Gunes G, Genc FM, et al. The prevalence of nutritional anemia in pregnancy in an east Anatolian province, Turkey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(329) doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Chowdhury HA, Ahmed KR, Jebunessa F, Akter J, Hossain S, Shahjahan M. Factors associated with maternal anemia among pregnant women in Dhaka city. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0234-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alem M, Enawgaw B, Gelaw A, Kena T, Seid M, Olkeba Y. Prevalence of anemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Azezo health Center Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia. J Interdiscipl Histopathol. 2013;1(3):137–144. doi: 10.5455/jihp.20130122042052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balarajan Y, Ramakrishnan U, Ozaltin E, Shankar AH, Subramanian SV. Anemia in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011;378(9809):2123–2135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CSA I. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2011. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland: Central Statistical Agency and ICF International. 2012.

- 10.Baig-Ansari N, Badruddin SH, Karmaliani R, Harris H, Jehan I, Pasha O, et al. Anemia prevalence and risk factors in pregnant women in an urban area of Pakistan. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29(2):132–139. doi: 10.1177/156482650802900207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gebre A, Mulugeta A. Prevalence of Anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in north western zone of Tigray, northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Nutri Metab. 2015;2015:165430. doi: 10.1155/2015/165430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melku M, Addis Z. Prevalence and predictors of maternal Anemia during pregnancy in Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia: An Institutional Based Cross-Sectional Study. Anemia. 2014;2014:108593. doi: 10.1155/2014/108593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alemu T, Umeta M. Reproductive and obstetric factors are key predictors of maternal Anemia during pregnancy in Ethiopia: evidence from demographic and health survey (2011) Anemia. 2015;2015:649815. doi: 10.1155/2015/649815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alene KA, Dohe AM. Prevalence of Anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in an urban area of eastern Ethiopia. Anemia. 2014;2014:561567. doi: 10.1155/2014/561567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Obse N, Mossie A, Gobena T. Magnitude of anemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Shalla Woreda, west Arsi zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2013;23(2):165–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kedir H, Berhane Y, Worku A. Khat chewing and restrictive dietary behaviors are associated with anemia among pregnant women in high prevalence rural communities in eastern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lelissa D, Yilma M, Shewalem W, Abraha A, Worku M, Ambachew H, et al. Prevalence of Anemia among women receiving antenatal Care at Boditii Health Center, southern Ethiopia. Clin Med Res. 2015;4(3):79–86. doi: 10.11648/j.cmr.20150403.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baingana RK, Enyaru JK, Tjalsma H, Swinkels DW, Davidsson L. The etiology of anemia during pregnancy: a study to evaluate the contribution of iron deficiency and common infections in pregnant Ugandan women. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(8):1423–1435. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014001888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muhangi L, Woodburn P, Omara M, Omoding N, Kizito D, Mpairwe H, et al. Associations between mild-to-moderate anemia in pregnancy and helminthes, malaria and HIV infection in Entebbe, Uganda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101(9):899–907. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glover-Amengor M, Owusu WB, Akanmori BD. Determinants of anemia in pregnancy in Sekyere West District, Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2005;39(3):102–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Idowu OA, Mafiana CF, Sotiloye D. Anaemia in pregnancy: a survey of pregnant women in Abeokuta, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2005;5(4):295–299. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2005.5.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tandu-Umba B, Mbangama AM. Association of maternal anemia with other risk factors in occurrence of great obstetrical syndromes at university clinics, Kinshasa, DR Congo. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:183. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0623-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliveira AC, Barros AM, Ferreira RC. Risk factors associated among anemia in pregnancy women of network public health of a capital of Brazil Northeastern. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2015;37(11):505–511. doi: 10.1590/SO100-720320150005400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maskey M, Jha N, Poudel S, Yadav D. Anemia in pregnancy and its associated factors: a study from eastern Nepal. Nepal J Epidemiology. 2014:4(4).

- 25.Asossa Zone Health Department. Annual report Health Development Army. Annual report. 2007.

- 26.Sullivan KM, Mei Z, Grummer-Strawn L, Parvanta I. Haemoglobin adjustments to define anaemia. Tropical Med Int Health. 2008;13(10):1267–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Hemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anemia and assessment of severity. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011.

- 28.WHO. World Health Organization body mass index (BMI) classification. In. www.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html. Accessed 29 Aug 2013.

- 29.Kennedy G, Ballard T, Dop MC. Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity: food and agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nwizu EN, Iliyasu Z, Ibrahim SA, Galadanci HS. Socio-demographic and maternal factors of Anemia in pregnancy at booking in Kano, northern Nigeria, African. Afr J Rep Health. 2011;15(4):33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abriha A, Yesuf ME, Wassie MM. Prevalence and associated factors of anemia among pregnant women of Mekelle town: a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:888. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Getachew M, Yewhalaw D, Tafess K, Getachew Y, Zeynudin A. Anemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women in Gilgel gibe dam area, Southwest Ethiopia. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:296. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olatunbosun OA, Abasiattai A, Bassey EA, James RS, Ibanga G, Morgan A. Prevalence of Anemia among pregnant women at booking in the University of Uyo Teaching Hospital, Uyo, Nigeria. Biomed Res Int. 2014;18(1):44–53. doi: 10.1155/2014/849080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Douamba Z, Bisseye C, Djigma FW, Compaore TR, Bazie VJ, Pietra V, et al. Asymptomatic malaria correlates with anemia in pregnant women at Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:198317. doi: 10.1155/2012/198317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mbule MA, Byaruhanga YB, Kabahenda M, Lubowa A. Determinants of anemia among pregnant women in rural Uganda. Rural Remote Health. 2013;13(2):2259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jufar AH, Zewde T. Prevalence of Anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal Care at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa Ethiopia. J Hematol Thrombo, Dis. 2013;2(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sukrat B, Suwathanapisate P, Siritawee S, Poungthong T, Phupongpankul K. The prevalence of iron deficiency anemia in pregnant women in Nakhonsawan, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93(7):765–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karaoglu L, Pehlivan E, Egri M, et al. The prevalence of nutritional anemia in pregnancy in an east Anatolian province, Turkey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:329. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahavarkar SH, Madhu CK, Mule VD. A comparative study of teenage pregnancy. J Obstet and Gynecol. 2008;28(6):604–607. doi: 10.1080/01443610802281831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.WHO. Adolescent development: Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health/ http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/development/en/. Accessed 11 Feb 2015.

- 41.Beard JL. Iron status before childbearing, iron requirements in adolescent females. J Nutr. 2000;130:440S–442S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.440S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Bank. Adolescent Nutrition: Public Health at Glance: http://web.worldbank.org/archive/website01213/WEB/0__CO-82.HTM In. June 2003.

- 43.Hyder SM, Haseen F, Khan M, Schaetzel T, Jalal CS, Rahman M, et al. Multiple-micronutrient-fortified beverage affects hemoglobin, iron, and vitamin a status and growth in adolescent girls in rural Bangladesh. J Nutr. 2007;137(9):2147–2153. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.9.2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bharati P, Som S, Chakrabarty S, Bharati S, Pal M. Prevalence of anemia and its determinants among non-pregnant and pregnant women in India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2008;20(4):347–359. doi: 10.1177/1010539508322762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biswas M, Baruah R. Maternal anemia associated with socio-demographic factors among pregnant women of Boko-Bongaon block Kamrup, Assam. Indian Journal of Basic and Applied Medical Research. 2014;3(2):712–721. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gebremedhin S, Enquselassie F, Umeta M. Prevalence and correlates of maternal Anemia in rural Sidama, southern Ethiopia. Afr J Reprod Health. 2014;18:44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ritsuko Aikawa NCK, Satoshi S, Binns CW. Risk factors for iron-deficiency anemia among pregnant women living in rural Vietnam. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(4):443–448. doi: 10.1079/phn2005851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Antelman G, Msamanga GI, Spiegelman D, Urassa EJN, Narh R, Hunter DJ, Fawzi WW. Nutritional factors and infectious disease contribute to anemia among pregnant women with human immunodeficiency virus in Tanzania. J Nutr. 2000;130(8):1950–1957. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.8.1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mom M. Anemia in pregnancy. 2011 Jan 2011.

- 50.Allen LH, Ahluwalia N. Improving iron status through diet: The application of knowledge concerning dietary iron bioavailability in human populations. Arlington VA:OMNI/John Snow, Inc., 1997.

- 51.Gebremedhin S, Enquselassie F. Correlates of Anemia among women of reproductive age in Ethiopia: evidence from Ethiopian DHS. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2005;25:22–30. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Collings R, Fairweather-Tait SJ, Dainty JR, Roe MA. Low-pH cola beverages do not affect women's iron absorption from a vegetarian meal. J Nutr. 2011;141(5):805–808. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.136507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kowalski A, Grant F, Okuku H, Wanjala R, Low J, Cole D, Levin C, Girard AW. Determinants of Anemia and iron status among pregnant women participating in the mama SASHA cohort study of vitamin a in western Kenya: preliminary findings (624.8). FASEB J. 2014;28(1 Supplement):624–8.

- 54.Mondal B, Tripathy V, Gupta R. Risk factors of Anemia during pregnancy among the Garo of Meghalaya, India. J Hum Ecol. 2006;14:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Makhoul Z, Taren D, Duncan B, et al. Risk factors associated with Anemia, iron deficiency and iron deficiency Anemia in rural Nepali pregnant women. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2012;43:735–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bondevik GT, Lie RT, Ulstein M, Kvale G. Maternal hematological status and risk of low birth weight and preterm delivery in Nepal. Acta Obstt Gynaecol Scand. 2001;80:402–408. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.080005402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Castaño F, Norton MH. Effects of birth spacing on maternal, perinatal, infant, and child health: a systematic review of causal mechanisms. Stud Fam Plan. 2012;43(2):93–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dewey KG, Cohen RJ. Does birth spacing affect maternal or child nutritional status? A systematic literature review. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2007;3(3):151–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wardlaw G, Kessel M. Perspective in nutrition. 5th ed. New York, McGraw Hill, Boston Burr Ridge; 2002. p. 157–98.

- 60.Dalenius K, Brindley PL, Smith BL, Reinold CM, Grummer-Strawn L. Pregnancy nutrition surveillance: 2010 report. 2012.

- 61.Bisoi S, Haldar D, Majumdar TK, Bhattacharya GN, Ray SK. Correlates of anemia among pregnant women in a rural area of West Bengal. J Fam Welf. 2011;57:72–78. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh R, Singh AK, Gupta AC, Singh HK. Correlate of anemia in pregnant women. Indian journal of community health. 2015;27:351–355. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jufar AH, Zewde T. Prevalence of Anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal Care at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa Ethiopia. Hematol Thromb Dis. 2014;2:1. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olatunbosun OA, Abasiattai AM, Bassey EA, James RS, Ibanga G, Morgan A. Prevalence of anemia among pregnant women at booking in the University of Uyo Teaching Hospital, Uyo, Nigeria. Bio Med Res Int. 2014;2014:849080. doi: 10.1155/2014/849080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the required data is available in the main paper.