Abstract

Medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) are known and have been long in use for a variety of health and cosmetics applications. Potential pharmacological usages that take advantage of bioactive plant-derived compounds' antimicrobial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties are being developed and many new ones explored. Some phytochemicals could trigger ROS-mediated cytotoxicity and apoptosis in cancer cells. A lot of effort has been put into investigating novel active constituents for cancer therapeutics. While other plant-derived compounds might enhance antioxidant defenses by either radical scavenging or stimulation of intracellular antioxidant enzymes, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to oxidative stress is one of the strategies that may show effective in damaging cancer cells. The biochemical pathways involved in plant-derived bioactive compounds' properties are complex, and in vitro platforms have been useful for a comprehensive understanding of the mechanism of action of these potential anticancer drugs. The present review aims at compiling the findings of particularly interesting studies that use cancer cell line models for assessment of antioxidant and oxidative stress modulation properties of plant-derived bioactive compounds.

1. Introduction

Cell culture techniques allow investigators to look in vitro into the effect of plant compounds under controlled conditions that ensure consistency and reproducibility of results. Nevertheless, interactions with other cell types are not usually considered in cell culture assays, so that the in vivo environment might not be fully mimicked. As a consequence, experimental design should be done carefully, with appropriate controls included in every assay [1].

There are several strategies for oxidative stress modulation such as ionizing radiation [2] and platinum coordination complexes [3], which are widely used in cancer treatment that significantly increases ROS expression levels. Furthermore, radiation exposure generates high production of NADPH oxidase, causing persistent OS [4]. Other interesting examples are anthracyclines, which induce production of superoxide radicals [5] and arsenic trioxide drugs that stimulate ROS production within the mitochondria via p53 activation [6]. In recent years, however, there is a growing interest in medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) and their antioxidant and oxidative stress modulation properties. This field of research looks particularly interesting for cancer therapeutics. A sizeable part of this research is made on cancer cell models. In the next sections, an overview of in vitro assessment of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) regarding their antioxidant and oxidative stress-modulating properties in cancer cell lines is presented.

2. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants

Medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) are vegetal materials that have pharmacological properties and also have aromatic and gastronomic uses [7]. The use of MAPs for drug preparation dates from approximately 5000 years ago [8], but nowadays, phytochemicals are involved in the formulation of medicines, food supplements, cosmetics, and other health-related products. In fact, approximately 50% of all drugs currently in clinical trials are derived from plants [9].

It is estimated that more than 80% of the world's medicinal plants grow in Asia and America [7, 10]. MAPs may exert several biological functions, for instance, extracts from MAPs could act as antimicrobial agents and reduce significantly the viability of pathogens of clinical and plant pathology interest. In the light of the increasing problem of antibiotic resistance, the antimicrobial properties of plant extracts may be of high value in clinical medicine. Some bioactive compounds have shown antifungal activity, which is also of interest in medicine, in pharmaceutics, and in plant sciences [11].

Another application of herbal products takes advantage of their high flavonoid content that confers them free radical scavenging properties that may, in turn, reduce cellular oxidative damage and ultimately help in the maintenance of intracellular antioxidant defenses [12]. In addition, bioactive molecules extracted from MAPs have revealed anti-inflammatory properties through TNF-α inhibition and in vitro decrease of nitric oxide generation [13]. Natural antioxidants might be more beneficial than synthetic ones, with the latter causing potential health side effects during long intake periods [14].

Since the discovery of the vinca alkaloids in the 1950s and their further application in cancer therapy, the interest in MAPs has increased [15]. The chemical components of many MAPs have been used in large extent for pharmaceutical studies. Bioactive compounds from plants had led to the discovery of several drugs with potential therapeutic value in cancer [16].

A number of plant-based anticancer drugs are currently under clinical studies [17] (see Table 1). Amin et al. [18] have classified plant-derived anticancer drugs into four classes according to their mechanisms of action: (1) methyl transferase inhibitors, (2) antioxidants, (3) histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi), and (4) mitotic disruptors. Methyl transferase inhibitors prevent cytosine methylation in CpG islands related to alterations in chromatin, causing gene silencing. The net effect is cell death via apoptosis [19]. The second class, antioxidants, can scavenge free radicals, preventing, therefore, ROS-related cellular and DNA damage. Inhibitors of histone deacetylases, the third group of plant-derived drugs act also as proapoptotic agents, by activating either the intrinsic or extrinsic pathway [20]. This type of inhibitors, however, might trigger cell death processes via necrosis and autophagy in some cell lines [21]. Finally, the fourth group, mitotic disruptors, cause damage to tubulin in the microtubules; hence, they prevent cell division and induce apoptosis [22].

Table 1.

Plant-derived natural products approved for cancer treatment.

| Class | Isolated from | Mechanism of action | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vinca alkaloids (vinblastine, vincristine, vinorelbine, vinflunine) | Catharanthus roseus or Vinca rosea | Disruption of formation of the mitotic spindle; tubulin inhibitors; deregulation of actin cytoskeletons; microtubule destabilization and depolymerization; cell death via apoptosis. | [23, 24] |

| Epipodophyllotoxins (etoposide, teniposide, etoposide phosphate) | Podophyllum peltatum L. | Cell cycle arrest; DNA strand damage; cell death via apoptosis. | [25, 26] |

| Taxanes (paclitaxel, paclitaxel albumin-stabilized nanoparticle formulation, docetaxel, cabizitaxel) | Taxus brevifolia L. | Mitotic inhibitors; microtubule disruptors; apoptosis is induced through stabilization of microtubules. | [27] |

| Camptothecins (irinotecan and topotecan) | Camptotheca acuminata | Inhibition of the nuclear protein topoisomerase I. | [28] |

3. Oxidative Stress

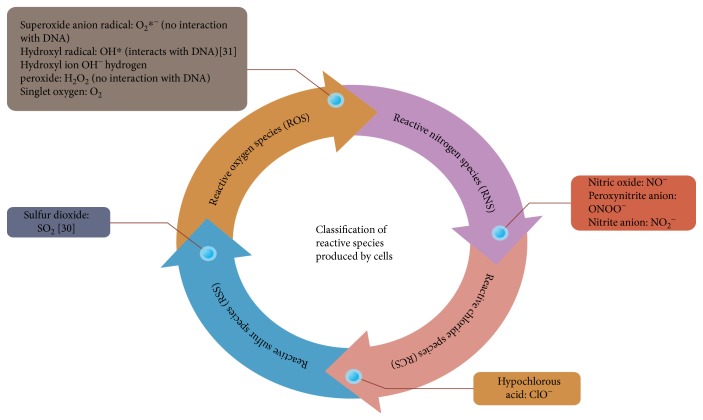

In eukaryotic cells, the most important redox process is aerobic respiration, which is mediated by mitochondrial electron transfer. This leads to the generation, in turn, of most of the endogenous intracellular reactive species (RS). For a proposed classification of RS that are produced within cells, see Figure 1 [29].

Figure 1.

Classification of reactive species produced by cells [30, 31].

Generation of RS might be (1) exogenous, from sources such as UV radiation, toxic chemicals, cigarettes, drugs, pollutants, alcohol, physiological changes (aging, injury, and inflammation), and exercise or (2) endogenous, from intracellular sources including peroxisomes, mitochondrial metabolism, and the NADPH oxidase complex and myeloperoxidases, which play a fundamental role in maintaining a balanced cellular metabolism [32].

Oxidative stress (OS) is defined as an imbalance in ROS levels and cellular antioxidant endogenous mechanisms. Although ROS are involved in innate immunity and inflammatory signaling through pathogen elimination [32], ROS precise functions inside the complex metabolic network, however, are not clear [33].

High ROS concentrations have a major negative impact in biomolecules (nucleic acids, lipids, and proteins) [34], with high levels of ROS associated with atherosclerosis, cancer, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular diseases, chronic inflammation, stroke, and septic shock [35–38].

Intracellular ROS reduction is regulated by antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidases (GPx), catalases (CAT), and superoxide dismutases (SOD). However, in some cases, antioxidant defense mechanisms may be not enough to maintain a redox balance and might become easily saturated, causing permanent genome impairment and toxicity [39].

In cancerous cell lines, high levels of ROS are necessary to maintain a fast proliferation rate. Szatrowski and Nathan have reported that some cancer types such as melanoma, neuroblastoma, colon carcinoma, and ovarian carcinoma generate large quantities of hydrogen peroxide [40]. Furthermore, several oncogenes and tumor suppressors are affected by the presence of ROS [41]. Chemotherapy and radiation treatments increase intracellular ROS in order to eliminate cancer cells, but ROS production affects also surrounding normal cells, generating in turn damage to DNA and to several other biomolecules [42]. At the cellular level, ROS production effects are dose-dependent. A comprehensive understanding, however, of the complex ROS network, cytotoxicity pathways, and involved molecular metabolic mechanisms as a whole requires extensive analysis and experimentation.

The number of publications, in a PubMed search for in vitro effects of plant extracts on cancer cell lines, has increased substantially over the last 10 years, as shown in Figure 2. This reflects on the potential value and interest in research regarding bioactive compounds from plants and cancer.

Figure 2.

Number of publications related with plant extracts, cancer, and in vitro.

4. In Vitro Cell Line Models

Cell culture techniques provide a relatively easy and affordable way into eukaryotic experimentation. Cell culture is a very useful tool for the study of pathologic/normal mechanisms in cell biology and is considered essential when screening for potential new drugs for complex diseases, such as cancer. The use of a primary culture from certified vendors and proper culture media with adequate supplements and growth factors are crucial to secure consistent and stable in vitro cell functions. The use of immortalized cell lines facilitates in vitro research, but normal cell lines need to be included as experimental controls [43].

Cell line models have been widely used in OS research and also in the study of new candidate molecules for the treatment of OS-related diseases. For instance, procarbazine, an azo derivative, has been part of cancer treatment schemes since its discovery 50 years ago. Procarbazine's mechanism of action as anticancer drug involves oxidation of the molecule and production of intracellular hydrogen peroxide [44].

Regulation of ROS is fundamental for homeostasis and normal functioning of cells. Several studies have addressed this complex series of phenomena. For instance, in a study by Schlenker et al., OS was evaluated using a bile duct epithelial cell (BDE) model to determine the earliest effects of RS in cell injury. The study authors found that OS causes a significant decrease in cell volume and affects multiple cell functions such as ion permeability, activation of ion channels, and apoptosis [45]. Glorieux et al. [39] compared the expression of catalase in two cell line models (250MK normal mammary epithelial primary cells and MCF-7 breast adenocarcinoma cells) and evaluated OS resistance to extended exposure to high hydrogen peroxide concentrations. The results showed overexpression of catalase in the MCF7 model, suggesting that adaptive responses to oxidative stress might be regulated by chromatin remodeling.

As shown in Figure 2, research on in vitro screening of MAP-derived antioxidants has been on the rise in the last years. In the next section, we will look at several promising applications of MAPs based on data from in vitro cancer studies.

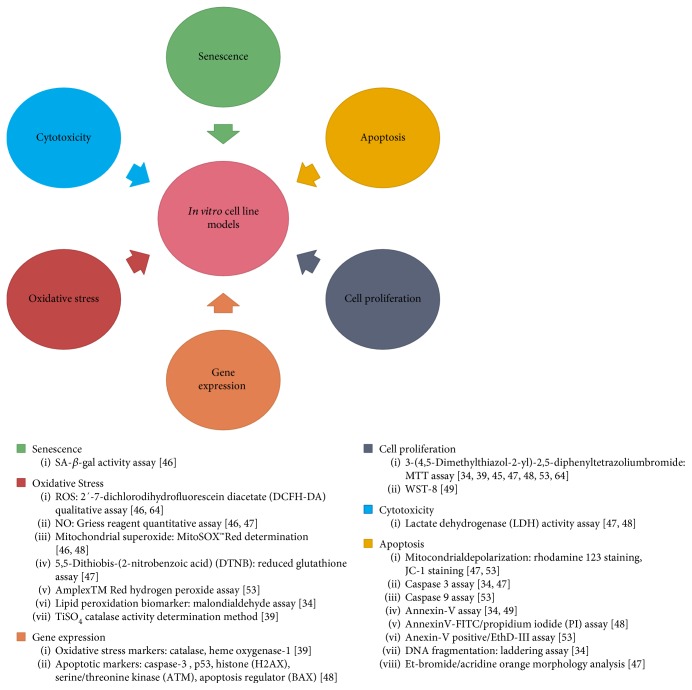

The methodology used in all the studies presented in this review has been summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Most commonly used methods for MAP evaluation on in vitro cancer cell line models.

4.1. MAPs: New Anticancer Compounds

4.1.1. Garlic

A study by Yedjou and Tchounwou evaluated the effect of garlic extract in an HL-60 model (human leukemia cells). This extract was found cytotoxic (via apoptosis) and an inductor of oxidative stress on tested cells. An interesting finding of the above study is the potential of malondialdehyde (MDA) as a biomarker of oxidative stress associated with caspase activation and DNA fragmentation. Mechanistic data regarding the observed cell responses to garlic extract is, however, still lacking [34].

4.1.2. Apigenin

In a study on the in vitro effect of apigenin, a natural polyphenolic compound rich in flavones, on cell lines HT-29 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma) and HCT-15 (Dukes' type C-colorectal adenocarcinoma) models, the authors [46] showed that apigenin has significant antiproliferative and proapoptotic properties. Apigenin's mechanism of action includes reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential and production of free radical species, including mitochondrial superoxide. Apigenin is also a senescence inductor and thus is potentially suitable for cell-based models in aging research.

4.1.3. Le Pana Guliya (LPG)

The anticancer properties of this herbal mixture used in traditional medicine have been assessed on several cancer cell lines (HepG2-hepatocellular carcinoma, HeLa-cervix adenocarcinoma, and CC1-normal rat fibroblasts) [47]. In the above work, the authors found that LPG had an intense antiproliferative effect on HepG2 and HeLa cells after 24 hours of exposure. LPG caused a reduction of protein synthesis in both cell lines in comparison to the normal CC1 line control. Glutathione (GSH) and nitric oxide (NO) measurements confirmed induction of oxidative stress, while LPG-mediated caspase activation and DNA fragmentation confirmed a proapoptotic effect of the mixture on the specific cell lines studied.

4.1.4. Caffeic Acid (CA)

Chemotherapeutics are usually toxic for both noncancer and cancer cells. Appropriate combinations of available drugs are crucial to effectively kill cancer cells, reduce side effects and improve survival rates. A study by Tyszka-Czochara et al. [48] evaluated the individual and combinatory effects of synthetic metformin (Met) and the natural polyphenolic antioxidant caffeic acid (CA) on HTB-34 cells (cervical epidermoid carcinoma). The authors found that CA activates 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), involved in cell energy regulation. Met downregulates several enzymes (ACLY, FAS, ELOVL6, and SCD1). Although both agents have apoptotic effects in cancer cells, CA specifically increases ROS production, meanwhile Met inhibits fatty acid biosynthesis. When tested in combination, a significant antiproliferative net effect was shown.

4.1.5. Bigelovin

The effect of this sesquiterpene lactone naturally produced by Inula helianthus aquatic on HT-29 and HCT 116 colorectal cancer cell lines was studied in a recent work by Li et al. [49]. The authors found a marked antiproliferative effect caused by apoptosis induction. The mechanism of action is a rise in ROS production in a process that involves several steps: (1) multi-caspase activation, (2) G2/M cell cycle arrest, and (3) DNA damage mediated by upregulation of death receptor 5 (DR5). These results support further research on a potential use of bigelovin in colorectal cancer therapeutics.

4.1.6. Linalool

Iwasaki et al. in a recently published work [50] studied the anticancer properties of this monoterpenoid alcohol found in more than 200 plant species. The authors exposed HCT116 (colorectal carcinoma) and CCD-18Co (human colon fibroblast) cells to linalool and observed inhibition of cell proliferation by induction of apoptosis via hydroxyl radical-mediated OS. Interestingly, a lipid peroxidation marker for oxidative stress was also found. Results of the above work suggest that linalool may be a potentially valuable compound for novel chemotherapeutics due to its antiproliferative properties on targeted cancer cells.

4.1.7. Curcumin

Curcumin is a bioactive compound isolated from Curcuma longa L. that has shown many pharmacological activities, such as modulation of the nuclear NF-κB signaling pathway. Hong et al. [51] showed that curcumin nanosuspensions exert a dose-dependent cytotoxic effect on HeLa and HepG2 cell lines. Additionally, when comparing the nanosuspension with curcumin solution, curcumin nanoscale preparations showed to be more toxic presumably because nanostructures might enter the tumor via endocytosis. In another study by Banerjee et al., the synergistic effect of curcumin and docetaxel, a chemotherapeutic used in metastatic prostate cancer, was tested. Stronger cytotoxicity and proapoptotic effects, as well as reduced expression of CDK-1 and COX-2 were demonstrated when exposing human prostate cancer DU145 and PC3 cells to a combination of both agents [52].

4.2. MAPs: ROS Protective Agents in Cancer Research

The role of natural antioxidants in oxidative stress-related diseases has been studied for several years. MAPs can act as protective agents against OS and thus their potential for use in such diseases might be worth exploring.

A study of five antioxidant fractions from seaweed Fucus spiralis on H₂O₂-treated MCF-7 cells (breast adenocarcinoma) [53] showed a reduction of ROS production, induction of apoptosis through caspase 9 activation, and depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane. From the five antioxidant fractions studied in the above work, only the F4 fraction revealed biological significance showing cytoprotective properties against hydrogen peroxide toxicity, with an interesting potential use as oxidative stress modulator.

In another recent study, Giacoppo et al. [54] evaluated the effect of cannabigerol (CBG), from Cannabis sativa, on a hydrogen peroxide ROS-induced murine RAW 264.7 macrophage model. This study identified the selective receptor antagonists needed to elucidate CBG's known antioxidant properties at the mechanistic level. The authors found that activation of CB2 receptors is involved in CBG effects, with receptor inhibition leading to lower oxidation as a cytoprotective effect. CBG was found to downregulate several oxidative markers through inhibition of phosphorylation and modulation of MAPK. In addition, CBG exerted antioxidant activity by inducing superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD-1) overexpression, which causes an imbalance in proapoptotic factors to avoid cell death.

Plant compounds such as flavonoids, polysaccharides, and phytohormones could function as radioprotectors, meaning they can protect adjacent normal cells from the harmful effects of radiation therapy. It has been proposed that the above compounds might also offer protection against ionizing occupational and environmental radiation exposure [42]. In a recently published study, Szejk et al. [10] demonstrated that the pretreatment of human lymphocytes with some polyphenolic compounds isolated from plants from the Rosaceae/Asteraceae family could prevent (60)Co γ-radiation DNA damage in exposed lymphocytes. Furthermore, these natural polyphenols could inhibit lipid peroxidation and activate antioxidant enzymes.

Conversely, plant products could act as radiosensitizers by enhancing the effect of ionizing radiation therapy against radioresistant cells. A study conducted by Wang et al. [55] showed that resveratrol, a well-known antioxidant compound, operate synergistically with ionizing radiation to induce autophagy, cause DNA damage, induce apoptosis, and inhibit DNA repair in a glioma stem cell line SU-2 model. In a study by Sayin et al. [56], resveratrol showed antioxidant activity either by ROS-scavenging or by intracellular antioxidant-enzyme induction in human normal cell lines (coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAEC)). The above study's data suggest that resveratrol could help prevent diseases related with the harmful and accumulative effect of ROS.

Lastly, it is important to mention that many studies currently in place evaluate the protective effect of novel antioxidant plant compounds against oxidative stress. Due to the complexity of biological systems, an interesting approach in antioxidant molecules testing might be the construction of an in vitro oxidative stress cell model. Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical that is frequently used for oxidative stress induction in cultured cells; however, concentrations and exposure times vary extensible and may require standardization to assure reproducibility and data comparability [56–58].

5. Conclusion

The use of in vitro cell models is critical for a comprehensive understanding of the biological properties of plant-derived compounds in cancer research. According to the European Union Reference Laboratory for Alternatives to Animal Testing (EURL-ECVAM), there are several in vitro cell models accepted for drug development applications. In the case of oxidative stress, studies on cell models help to integrate multiple metabolic routes and identify novel plant-based drugs or therapeutic targets. For instance, human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC) might be a valuable model for neurotoxicity studies with the use of the oxidative stress biomarker Nrf2 [59]. Such a model would also be an interesting addition to the currently available in vitro toxicology testing platforms.

Evaluation of potential natural drugs for modulation of oxidative stress in cancer might, in our opinion, be addressed efficiently and rigorously using cell line models. The NCI60 human tumor cell line anticancer drug screen panel had been used for testing of natural crude extracts collections since 1989. The panel requires previous individual cell line screening, which has led, for example, to the discovery of bortezomib, the first therapeutic proteasome inhibitor for the treatment of multiple myeloma [60].

Additionally, it is important to consider that a wide range of subtypes of cancer cell lines is currently available through certified vendors and collections. Colorectal cancer cell lines, for instance, show different genomic patterns and mRNA expression profiles [61] and may also show common mutations [62]. Therefore, the use of appropriately cultured cells with authenticated genetic and biochemical profiles, along with information on receptors, ion channels, and receptor signaling pathways are essential if reliable data is wanted from assays that assess the potential therapeutic properties of plant-derived biocompounds. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) [63] offers robust preclinical information that integrates the genomic diversity of several human cancers and may facilitate new drug discovery strategies.

In conclusion, carefully planned experiments on cell culture models allow a throughout assessment of the molecular pathways involved in the mechanism of action of a bioactive compound. The use of these models for evaluation of ROS production and oxidative stress modulation properties of plant-derived biocompounds is well documented and growing. Consequently, in vivo experiments with animal models might be optimized based on in vitro data. Information from in vitro and in vivo studies will, in turn, facilitate and improve further clinical trials [49].

6. New Perspectives

Cell culturing aims at mimicking in vivo environment. Three-dimensional (3-D) cultures closely emulate tumor formation processes by synthetic tumor microenvironment mimics (STEMs). Models of human lung epithelial cells, pulmonary vascular endothelial cells, and human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells have been used for induction of ROS production and evaluation of upregulated efflux transporters [64]. Finally, new genome editing technologies such as CRISPR are currently in use for the study of molecular level responses to plant-derived bioactive compounds. Potential chemotherapeutic uses of these compounds for modulation of oxidative stress or ROS-mediated selective toxicity might, by this means, be explored using fast and affordable novel strategies.

Abbreviations

- (60)Co:

Cobalt-60

- ACLY:

ATP citrate lyase

- AMPK:

5′-Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- ATM:

ATM serine/threonine kinase

- BAX:

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- BDE:

Bile duct epithelial cells

- CA:

Caffeic acid

- CAT:

Catalases

- CB2:

Cannabinoid receptor type 2

- CBG:

Cannabigerol

- CC1:

Normal rat fibroblast cell line

- CCD-18Co:

Homo sapiens colon normal cell line

- CCLE:

Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia

- CDK-1:

Cyclin-dependent kinase 1

- COX-2:

Cyclooxygenase-2

- CRISPR:

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- DCFH-DA:

Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- DNA:

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- DR:

Death receptor

- DTNB:

5,5-Dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)

- DU145:

Human prostate cancer cell line

- ELOVL6:

ELOVL fatty acid elongase 6

- EURL-ECVAM:

European Union Reference Laboratory for Alternatives to Animal Testing

- FAS:

Fatty acid synthase

- GPx:

Glutathione peroxidases

- GSH:

Glutathione

- H₂O₂:

Hydrogen peroxide

- HCAEC:

Human coronary artery endothelial cells

- HCT 116:

Human colon carcinoma cell line

- HCT-15:

Dukes' type C-colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line

- HDACi:

Histone deacetylase inhibitors

- HeLa:

Cervix adenocarcinoma cell line

- HepG2:

Hepatocellular carcinoma cell line

- hiPSC:

Human-induced pluripotent stem cell

- HL-60:

Human promyelocytic leukemia cells

- HT-29:

Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line

- HTB-34:

Cervical epidermoid carcinoma cell line

- LDH:

Lactate dehydrogenase

- LPG:

Le Pana Guliya

- MAPK:

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MAPs:

Medicinal and aromatic plants

- MCF-7:

Human breast adenocarcinoma cell line

- MDA:

Malondialdehyde

- Met:

Metformin

- mRNA:

Messenger ribonucleic acid

- MTT:

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NADPH:

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced

- NCBI:

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NCI60:

The US National Cancer Institute (NCI) 60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen

- NF-κB:

Nuclear transcription factor-kappaB

- NO:

Nitric oxide

- Nrf2:

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- OS:

Oxidative stress

- PC3:

Human Caucasian prostate adenocarcinoma cell line

- PCR:

Polymerase chain reaction

- RAW 264.7:

Macrophage; Abelson murine leukemia virus transformed from mouse cell line

- ROS:

Reactive oxygen species

- RS:

Reactive species

- SA-βgal:

Senescence-associated β galactosidase

- SCD1:

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1

- SOD:

Superoxide dismutases

- STEMs:

Synthetic tumor microenvironment mimics

- SU-2:

Glioma stem cell line

- TiSO4:

Titanium(II) sulfate

- TNF-α:

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- WST-8:

Water soluble tetrazolium salt.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kaur G., Dufour J. M. Cell lines: valuable tools or useless artifacts. Spermatogenesis. 2012;2(1):1–5. doi: 10.4161/spmg.19885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshida T., Goto S., Kawakatsu M., Urata Y., Li T.-S. Mitochondrial dysfunction, a probable cause of persistent oxidative stress after exposure to ionizing radiation. Free Radical Research. 2012;46(2):147–153. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.645207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conklin K. A. Chemotherapy-associated oxidative stress: impact on chemotherapeutic effectiveness. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2004;3(4):294–300. doi: 10.1177/1534735404270335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y., Liu L., Pazhanisamy S. K., Li H., Meng A., Zhou D. Total body irradiation causes residual bone marrow injury by induction of persistent oxidative stress in murine hematopoietic stem cells. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2010;48(2):348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Šimůnek T., Štěrba M., Popelová O., Adamcová M., Hrdina R., Gerši V. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: overview of studies examining the roles of oxidative stress and free cellular iron. Pharmacological Reports. 2009;61:154–171. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller W. H., Schipper H. M., Lee J. S., Singer J., Waxman S. Mechanisms of action of arsenic trioxide. Cancer Research. 2002;62:3893–3903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kusuma I. W., Murdiyanto, Arung E. T., Syafrizal, Kim Y. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of medicinal plants used by the Bentian tribe from Indonesia. Food Science and Human Wellness. 2014;3(3-4):191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2014.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrovska B. B. Historical review of medicinal plants’ usage. Pharmacognosy Reviews. 2012;6(11):p. 1. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.95849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shakya A. K. Medicinal plants : future source of new drugs. International Journal of Herbal Medicine. 2016;4(4):59–64. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.1395.6085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szejk M., Poplawski T., Sarnik J., et al. Polyphenolic glycoconjugates from medical plants of Rosaceae/Asteraceae Family protect human lymphocytes against γ-radiation-induced damage. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2017;94:585–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh M. K., Pandey A., Sawarkar H., et al. Methanolic extract of Plumbago Zeylanica - a remarkable antibacterial agent against many human and agricultural pathogens. Journal of Pharmacopuncture. 2017;20(1):18–22. doi: 10.3831/KPI.2017.20.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilhem B., Fawzia A. B., Imad Abdelhamid E. H., Karima B., Fawzia B., Chahrazed B. Identification and in vitro antioxidant activities of phenolic compounds isolated from Cynoglossum cheirifolium L. Natural Product Research. 2017:1–5. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2017.1314286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigues M. J., Custódio L., Lopes A., et al. Unlocking the in vitro anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic potential of Polygonum maritimum. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2017;55(1):1348–1357. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2017.1301493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lahmar I., Belghith H., Ben Abdallah F., Belghith K. Nutritional composition and phytochemical, antioxidative, and antifungal activities of Pergularia tomentosa L. BioMed Research International. 2017;2017:9. doi: 10.1155/2017/6903817.6903817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prakash O., Kumar A., Kumar P., Ajeet A. Anticancer potential of plants and natural products: a review. American Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2013;1(6):104–115. doi: 10.12691/ajps-1-6-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grothaus P. G., Cragg G. M., Newman D. J. Plant natural products in anticancer drug discovery. Current Organic Chemistry. 2010;14(1):1781–1791. doi: 10.2174/138527210792927708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juárez P. Plant-derived anticancer agents: a promising treatment for bone metastasis. BoneKEy Reports. 2014;3 doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2014.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amin A., Gali-Muhtasib H., Ocker M., Schneider-Stock R. Overview of major classes of plant-derived anticancer drugs. International Journal of Biomedical Sciences. 2009;5(1):1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flis S., Gnyszka A., Flis K. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors improve the effect of chemotherapeutic agents in SW48 and HT-29 colorectal cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9(3, article e92305) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alam M. A., ISM Z., Ghafoor K., et al. In vitro antioxidant and, α-glucosidase inhibitory activities and comprehensive metabolite profiling of methanol extract and its fractions from Clinacanthus nutans. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2017;17(1):p. 181. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1684-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J., Zhong Q. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and cell death. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2014;71(20):3885–3901. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1656-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukhtar E., Adhami V. M., Mukhtar H. Targeting microtubules by natural agents for cancer therapy. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2014;13(2):275–284. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guetz S., Tufman A., von Pawel J., et al. Metronomic treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with daily oral vinorelbine - a phase I trial. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2017;10:1081–1089. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S122106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinghorn A. D., DE Blanco E. J., Lucas D. M., et al. Discovery of anticancer agents of diverse natural origin. Anticancer Research. 2016;36(11):5623–5637. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenwell M., Rahman P. K. S. M. Medicinal plants: their use in anticancer treatment. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research. 2015;6(10):4103–4112. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.6(10).4103-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molder A. L., Persson J., El-Schich Z., Czanner S., Gjorloff-Wingren A. Supervised classification of etoposide-treated in vitro adherent cells based on noninvasive imaging morphology. Journal of Medical Imaging. 2017;4(2, article 021106) doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.4.2.021106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vrignaud P., Semiond D., Benning V., Beys E., Bouchard H., Gupta S. Preclinical profile of cabazitaxel. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2014;8:1851–1867. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S64940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y. Q., Li W. Q., Morris-Natschke S. L., et al. Perspectives on biologically active camptothecin derivatives. Medicinal Research Reviews. 2015;35(4):753–789. doi: 10.1002/med.21342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krumova K., Cosa G. Singlet Oxygen: Applications in Biosciences and Nanosciences. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2016. Chapter 1. Overview of reactive oxygen species; pp. 1–21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dou K., Fu Q., Chen G., et al. A novel dual-ratiometric-response fluorescent probe for SO2/ClO– detection in cells and in vivo and its application in exploring the dichotomous role of SO2 under the ClO– induced oxidative stress. Biomaterials. 2017;133:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shigenaga M. K., Ames B. N. Oxidants and mitogenesis as causes of mutation and cancer: the influence of diet. Basic Life Sciences. 1993;61:419–436. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2984-2_37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morry J., Ngamcherdtrakul W., Yantasee W. Oxidative stress in cancer and fibrosis: opportunity for therapeutic intervention with antioxidant compounds, enzymes, and nanoparticles. Redox Biology. 2017;11:240–253. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira E. J., Smolko C. M., Janes K. A. Computational models of reactive oxygen species as metabolic byproducts and signal-transduction modulators. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2016;7:p. 457. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yedjou C. G., Tchounwou P. B. In vitro assessment of oxidative stress and apoptotic mechanisms of garlic extract in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Journal of Cancer Science & Therapy. 2012;2012(Supplement 3):p. 6. doi: 10.4172/1948-5956.S3-006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fridovich I. Fundamental aspects of reactive oxygen species, or what’s the matter with oxygen? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;893:13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giasson B. I. Oxidative damage linked to neurodegeneration by selective α-synuclein nitration in synucleinopathy lesions. Science. 2000;290(5493):985–989. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5493.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guzik T. J., Sadowski J., Guzik B., et al. Coronary artery superoxide production and nox isoform expression in human coronary artery disease. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2006;26(2):333–339. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000196651.64776.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huet O., Dupic L., Harrois A., Duranteau J. Oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction during sepsis. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2011;16:1986–1995. doi: 10.2741/3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glorieux C., Sandoval J. M., Fattaccioli A., et al. Chromatin remodeling regulates catalase expression during cancer cells adaptation to chronic oxidative stress. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2016;99:436–450. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szatrowski T. P., Nathan C. F. Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells. Cancer Research. 1991;51(3):794–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meng T. C., Fukada T., Tonks N. K. Reversible oxidation and inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases in vivo. Molecular Cell. 2002;9(2):387–399. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00445-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hazra B., Ghosh S., Kumar A., Pandey B. N. The prospective role of plant products in radiotherapy of cancer: a current overview. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2012;2:p. 94. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2011.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atanasov A. G., Waltenberger B., Pferschy-Wenzig E. M., et al. Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: a review. Biotechnology Advances. 2015;33(8):1582–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renschler M. The emerging role of reactive oxygen species in cancer therapy. European Journal of Cancer. 2004;40(13):1934–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlenker T., Schwake L., Voss A., Stremmel W., Elsing C. Oxidative stress activates membrane ion channels in human biliary epithelial cancer cells (Mz-Cha-1) Anticancer Research. 2015;35(11):5881–5888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banerjee K., Mandal M. Oxidative stress triggered by naturally occurring flavone apigenin results in senescence and chemotherapeutic effect in human colorectal cancer cells. Redox Biology. 2015;5:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wageesha N. D., Soysa P., Atthanayake K., Choudhary M. I., Ekanayake M. A traditional poly herbal medicine “Le Pana Guliya” induces apoptosis in HepG2 and HeLa cells but not in CC1 cells: an in vitro assessment. Chemistry Central Journal. 2017;11(1):p. 2. doi: 10.1186/s13065-016-0234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tyszka-Czochara M., Konieczny P., Majka M. Caffeic acid expands anti-tumor effect of metformin in human metastatic cervical carcinoma HTB-34 cells: implications of AMPK activation and impairment of fatty acids de novo biosynthesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(2) doi: 10.3390/ijms18020462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li M., Song L. H., Yue G. G., et al. Bigelovin triggered apoptosis in colorectal cancer in vitro and in vivo via upregulating death receptor 5 and reactive oxidative species. Scientific Reports. 2017;7, article 42176 doi: 10.1038/srep42176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iwasaki K., Zheng Y. W., Murata S., et al. Anticancer effect of linalool via cancer-specific hydroxyl radical generation in human colon cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016;22(44):p. 9765. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i44.9765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hong J., Liu Y., Xiao Y., et al. High drug payload curcumin nanosuspensions stabilized by mPEG-DSPE and SPC: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Drug Delivery. 2017;24(1):109–120. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2016.1233589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Banerjee S., Singh S. K., Chowdhury I., Lillard J. W., Jr, Singh R. Combinatorial effect of curcumin with docetaxel modulates apoptotic and cell survival molecules in prostate cancer. Frontiers in Bioscience (Elite Edition) 2017;9:235–245. doi: 10.2741/e798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pinteus S., Silva J., Alves C., Horta A., Thomas O. P., Pedrosa R. Antioxidant and cytoprotective activities of Fucus spiralis seaweed on a human cell in vitro model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(2):p. 292. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giacoppo S., Gugliandolo A., Trubiani O., et al. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors are involved in the protection of RAW264.7 macrophages against the oxidative stress: an in vitro study. European Journal of Histochemistry. 2017;61(1):1–13. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2017.2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang L., Long L., Wang W., Liang Z. Resveratrol, a potential radiation sensitizer for glioma stem cells both in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2015;129(4):216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sayin O., Arslan N., Sultan A. Z., Akdoğan G. In vitro effect of resveratrol against oxidative injury of human coronary artery endothelial cells. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences. 2011;41(2):211–218. doi: 10.3906/sag-0907-128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pitz H. S., Pereira A., Blasius M. B., et al. In vitro evaluation of the antioxidant activity and wound healing properties of Jaboticaba (Plinia peruviana) fruit peel Hydroalcoholic extract. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2016;2016:6. doi: 10.1155/2016/3403586.3403586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim J. H., Park E. Y., Ha H. K., et al. Resveratrol-loaded nanoparticles induce antioxidant activity against oxidative stress. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 2016;29(2):288–298. doi: 10.5713/ajas.15.0774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gan L., Johnson J. A. Oxidative damage and the Nrf2-ARE pathway in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2014;1842(8):1208–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shoemaker R. H. The NCI60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6(10):813–823. doi: 10.1038/nrc1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilding J. L., Mcgowan S., Liu Y., Bodmer W. F. Replication error deficient and proficient colorectal cancer gene expression differences caused by 3′ UTR polyT sequence deletions. PNAS. 2010;107(49):21058–21063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015604107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu Y., Bodmer W. F. Analysis of P53 mutations and their expression in 56 colorectal cancer cell lines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(4):976–981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510146103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barretina J., Caponigro G., Stransky N., et al. The cancer cell line encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483(7391):603–307. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lamichhane S. P., Arya N., Kohler E., Xiang S., Christensen J., Shastri V. P. Recapitulating epithelial tumor microenvironment in vitro using three dimensional tri-culture of human epithelial, endothelial, and mesenchymal cells. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):p. 581. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2634-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]