Abstract

Homocystinuria is the second most common treatable aminoacidopathy. Clinically, affected patients present with eye, skeleton, central nervous system, and most importantly, vascular system abnormalities. This autosomal recessive disorder leads to accumulation of homocysteine and its metabolites in the blood and urine. In this report, we present a case with clinical and biochemical findings of homocystinuria with stroke and a positive familial history of the disease in her brother. A 4-year-old girl was admitted to pediatric emergency ward because of acute onset of right hemiparesis and subsequent generalized tonic–clonic seizures. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging revealed acute infarct areas in the left cerebral hemisphere. Metabolic screening revealed elevated concentrations of serum homocysteine and methionine and a normal serum concentration of vitamin B12. These findings, along with a positive familial history led to the diagnosis of homocystinuria. In any child who presents with stroke, some rare condition such as homocystinuria should be considered in diagnosis.

Keywords: Homocystinuria, stroke, thrombosis

Introduction

Homocystinuria, a rare autosomal recessive disorder, is a defect in the transsulfuration pathway (homocystinuria I) or methylation pathway (homocystinuria II and III). Its prevalence has been estimated to be 1 in 344,000.[1]

It is a disorder of methionine metabolism, leading to an abnormal accumulation of homocysteine and its metabolites (methionine, homocysteine, and their S-adenosyl derivatives) in the blood and urine.

The clinical presentation of the disease includes eye, skeleton, nervous system, and most importantly, vascular system abnormalities.[2,3]

Non-neurologic manifestations of homocystinuria tend to become more apparent during late childhood. These may include tall stature with marfanoid habitus, arachnodactyly, osteoporosis with vertebral fractures, kyphoscoliosis, livedo reticularis, and malar flush. Hypopigmentation and premature graying of the hair are also common. Neuropsychiatric symptomatology has also been reported, including affective disorders, obsessive compulsive symptomatology, and personality disorders.[4,5] Metabolic screening shows elevated concentrations of serum homocysteine and methionine and a normal serum concentration of vitamin B12.

Increased carotid plaque thickness has been associated with high homocysteine and low B12 levels and subsequent higher risk of stroke. This association between homocystinuria and the vascular complications was first reported in 1976,[6] and since then, several studies have confirmed this association.[7,8] Thromboembolic events affect arteries and veins of all parts of the body, representing a major cause of morbidity and mortality.[9]

The most commonly reported events are cerebrovascular accidents, pulmonary embolism, and thrombosis of carotid and renal arteries.[9]

In this report, we present a 4-year-old girl with stroke, biochemical findings of homocystinuria, and a positive familial history of the disease in her brother who had lens dislocation surgery before.

Case Report

A 4-year-old girl was admitted to pediatric emergency of Imam Hossein Hospital, affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, in September 2012 with acute onset of right hemiparesis and subsequent generalized tonic–clonic seizure.

She was born of a consanguineous marriage. Her past medical history was unremarkable, and developmental milestones were within normal limits. Her weight, length, and head circumference were found to be concordant with her age.

Her family history revealed that she had an 11-year-old brother diagnosed with homocystinuria 4 years ago, who had not been treated before because of negligence by the family. He had marfanoid habitus, arachnodactyly, and history of lens dislocation surgery when he was 7 years old [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The case and her brother

Her neurologic examination revealed right hemiparesis. Extensor plantar response was positive on the right side.

She had normal cardiac findings. Ophthalmologic examination revealed bilateral lens subluxation.

Cranial magnetic resonance imaging revealed acute infarct areas in the left cerebral hemisphere. The coagulation profile was unremarkable, and the screening for autoimmune diseases yielded negative findings. Metabolic screening revealed elevated concentrations of serum homocysteine 202 μmol/l (normal range, 4.60–12.44 μmol/l) and methionine 523 μmol/l (normal range, 0–90 μmol/l) with a normal serum concentration of vitamin B12. Further investigations revealed positive results for homocysteine in the blood and urine.

Based on clinical and laboratory results, the diagnosis of homocystinuria was made.

Anticoagulation therapy (heparin followed by warfarin) was started along with antiepileptic medications. Furthermore, the patient was treated with folic acid, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and vitamin C. Later, betaine was added to her treatment.

Metabolic screening for homocystinuria was also positive in her brother.

The child improved gradually and showed signs of recovery. She started to walk and talk normally 8 weeks following treatment.

Discussion

The case reported here was a homocystinuria patient with stroke, seizure, and right-sided hemiparesis as her presenting signs. As far as our knowledge is concerned, only a few homocystinuria cases have been reported who presented with cerebral infarction in early childhood.[10]

Homocystinuria, the second most common treatable aminoacidopathy, is a defect in the transsulfuration pathway (homocystinuria I) or methylation pathway (homocystinuria II and III).

Homocystinuria type I, caused due to the deficiency of the enzyme cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS), is the most common inborn error of methionine metabolism.

It is an autosomal recessively inherited disorder of methionine metabolism. CBS is an enzyme that converts homocysteine to cystathionine in the transsulfuration pathway of methionine cycle and requires pyridoxal 5-phosphate as a cofactor. The other two cofactors involved in remethylation pathway of methionine include vitamin B12 and folic acid. The characteristic amino acid profile typical of homocystinuria due to CBS deficiency includes homocystinuria, hyperhomocysteinemia, hypermethioninaemia and low plasma cystine and cystathionine.[11]

Homocystinuria type II is characterized by the triad of megaloblastic anemia, homocystinuria, and hypomethioninemia.[10]

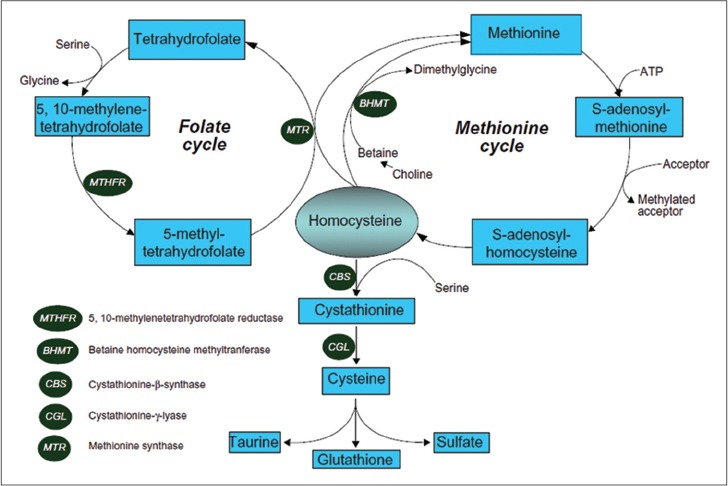

Deficiency of the enzyme methyltetrahydrofolate reductase results in homocystinuria type III, which is characterized by homocystinuria and homocystinemia with low or normal blood methionine levels[2] [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Homocysteine metabolic pathway. The case and her brother

Early vascular occlusion is the most serious complication in patients with homocystinuria. Approximately 40% of patients with homocystinuria will have a thromboembolic vascular lesion, which is the cause of disability and mortality in patients before the age of 20 years.[12]

Homocystinuria with stroke as the initial presentation under the age of 5 years has been reported rarely.[13,14] One of the previous cases was a girl aged 3 years and 9 months who presented with acute-onset right hemiparesis, subsequent generalized tonic–clonic seizures, and motor aphasia, in addition to coarse facial appearance, mild malar flushing, livedo reticularis on the extremities, and bilateral carotid bruits. Like our patient, she had bilateral lens dislocation without any skeletal abnormality.[10]

The mechanisms by which thrombosis and atherosclerosis result from hyperhomocysteinemia are not clear, but probably are due to endothelial injury and stimulation of platelet aggregation.[15]

The patient reported here presented with arterial thrombosis and laboratory findings of homocystinuria. When investigated, her brother also had classic form of the disease, but he had been left without treatment by his parents.

Approximately 50% of patients with homocystinuria are pyridoxine responsive and can be treated with high doses of vitamin B6 (500 mg/day). For nonresponders, therapy consists of folic acid supplement and trimethylglycine (also known as betaine) (6 g/24 h for adults or 150 mg/kg/day for children) to lower plasma disulfide metabolites.[10,15]

Similarly, our patient was treated with low-dose folic acid (10 mg/day), vitamin B12, vitamin C, and vitamin B6 (500 mg/day). Later, betaine (2 g/day) was added to the treatment. Vitamin C (1 g/day) prevents endothelial dysfunction in these patients and reduces the potential long-term risk of atherothrombotic disease [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

The case and her brother after treatment

Response to therapy in our patient was very good, but this is not always true. In one of the previous reports, in a case treated with folic acid (10 mg/day), vitamin B12, vitamin B6 (400 mg/day), and betaine (2 g/day), only partial response to therapy was seen. She was seizure free with partially treated aphasia in her last follow-up.[10]

Based on the fact that homocystinuria type I with stroke as the presenting sign in childhood is rare, our patient and her complete response to treatment proves to be a novel one.

Patients with homocystinuria should be monitored for complications that may occur if there is lack of response to the initial treatment.

In summary, homocystinuria should be investigated in any patient presenting with stroke or vasculopathy, even in the absence of other classic features of the disease.[10]

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mudd SH, Levy HL, Skovby F. Disorders of transsulfuration. In: Scriver CR, Sly WS, Childs B, Beaudet AL, Valle D, Kinzler KW, et al., editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995. pp. 12797–1327. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mudd SH, Skovby F, Levy HL, Pettigrew KD, Wilcken B, Pyeritz RE, et al. The natural history of homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:1–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Franchis R, Sperandeo MP, Sebastio G, Andria G. Clinical aspects of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency: How wide is the spectrum? The Italian Collaborative Study Group on Homocystinuria. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157(Suppl 2):S67–70. doi: 10.1007/pl00014309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao TN, Radhakrishna K, Mohana Rao TS, Guruprasad P, Ahmed K. Homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta synthase deficiency. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:375–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.42916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan MM, Sidhu RK, Alexander J, Megerian JT. Homocystinuria presenting as psychosis in an adolescent. J Child Neurol. 2002;17:859–60. doi: 10.1177/08830738020170111707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilcken DE, Wilcken B. The pathogenesis of coronary artery disease. A possible role for methionine metabolism. J Clin Invest. 1976;57:1079–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI108350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hankey GJ, Eikelboom JW. Homocysteine and vascular disease. Lancet. 1999;354:407–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)11058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mojiminiyi OA, Marouf R, Al Shayeb AR, Qurton M, Abdella NA, Al Wazzan H, et al. Determinants and associations of homocysteine and prothrombotic risk factors in Kuwaiti patients with cerebrovascular accident. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17:136–42. doi: 10.1159/000112968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Generoso A, Fowler B, Sebastio G. Disorders of sulfur amino acid metabolism. In: Fernandes J, Saudubray J, Berghe G, Walter J, editors. Inborn Metabolic Diseases: Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. Berlin: Springer; 2006. p. 27373. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alehan F, Saygi S, Gedik S, Kayahan Ulu EM. Stroke in early childhood due to homocystinuria. Pediatr Neurol. 2010;43:294–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andria G, Sebastio G. Homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency and related disorders. In: Femandes J, Saudubary JM, Van den Berghe G, editors. Inborn Metabolic Diseases Diagnosis and Treatment. 2nd ed. Berlin Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 1996. pp. 15177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardo E, Campistol J, Caritg J, Ruiz S, Vilaseca MA, Kirkham F, et al. Fatal haemorrhagic infarct in an infant with homocystinuria. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:132–5. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299000250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruysberg JR, Boers GH, Trijbels JM, Deutman AF. Delay in diagnosis of homocystinuria: Retrospective study of consecutive patients. BMJ. 1996;313:1037–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7064.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu CY, Hou JW, Wang PJ, Chiu HH, Wang TR. Homocystinuria presenting as fatal common carotid artery occlusion. Pediatr Neurol. 1996;15:159–62. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(96)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maclean KN. Betaine treatment of cystathionine b-synthase-deficient homocystinuria; does it work and can it be improved? Dove press. 2012;2:23–33. [Google Scholar]