Abstract

The approach to children with anogenital warts in the context of sexual abuse is a challenge in clinical practice. This study aims to review the current knowledge of anogenital warts in children, the forms of transmission, and the association with sexual abuse and to propose a cross-sectional approach involving all medical specialties. A systematic review of the literature was conducted in Portuguese and English from January 2000 to June 2016 using the ISI Web of Knowledge and PubMed databases. Children aged 12 years or younger were included. The ethical and legal aspects were consulted in the Declaration and Convention on the Rights of Children and in the World Health Organization. Non-sexual and sexual transmission events of human papillomavirus in children have been well documented. The possibility of sexual transmission appears to be greater in children older than 4 years. In the case of anogenital warts in children younger than 4 years of age, the possibility of non-sexual transmission should be strongly considered in the absence of another sexually transmitted infection, clinical indicators, or history of sexual abuse. The importance of human papillomavirus genotyping in the evaluation of sexual abuse is controversial. A detailed medical history and physical examination of both the child and caregivers are critical during the course of the investigation. The likelihood of an association between human papillomavirus infection and sexual abuse increases directly with age. A multidisciplinary clinical approach improves the ability to identify sexual abuse in children with anogenital warts.

Keywords: Childhood sexual abuse, Condyloma acuminata, Child, Papillomaviridae, Warts

INTRODUCTION

Anogenital infection caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI). Clinically, HPV may manifest as anogenital warts (AWs), also known as condyloma acuminata, in cases in which it infects mucous membranes. However, AW and condyloma acuminata are often used as synonyms.

The incidence of AWs in children has increased in recent decades.1,2 This increase has renewed the interest in understanding the mode of transmission of AWs, its social and legal impacts in cases of sexual abuse, and possible long-term complications.

The association between AWs in children and the occurrence of sexual abuse has been discussed. According to the World Health Organization, child abuse is defined as the abuse and neglect of all children younger than 18 years and includes all types of physical, psychological, and sexual abuse, as well as neglect and commercial exploitation.3 More specifically, sexual abuse of minors involves the sexual contact of a child by an adult or older child, with an age difference of at least 5 years and a significant difference in cognitive-affective development. This type of abuse also involves the participation of the minor in practices aimed at the gratification and satisfaction of an adult or older child who is in a position of power or authority over the child.4,5 The forms of sexual abuse considered in most studies are orogenital contact, genital-genital contact, genital-anal contact, caressing, digital penetration of the vagina or anus, and the introduction of objects into the vagina or anus.6

The difficulty in addressing suspicions of sexual abuse in children with AWs is due to the vulnerability of the child and the caregivers and to the ethical, medical, and legal aspects involved in the suspicion of this crime. Therefore, most healthcare professionals do not feel comfortable consulting potential victims or performing a detailed medical history and physical examination. This study aims to review the current knowledge of AWs in children, its form of transmission, and the association with sexual abuse and to propose a cross-sectional approach involving all medical specialties, without disregarding the children and caregivers.

METHODS

A systematic review of the literature in Portuguese and English from January 2000 to June 2016 was conducted using the databases ISI Web of Knowledge and PubMed and the following terms and keywords: "verrugas anogenitais", "anogenital warts" (MeSH), "condiloma acuminado", "condylomata acuminata" (MeSH), "criança", "child" (MeSH), "idade pediátrica", "pediatric age" (MeSH), "VPH", "HPV" (MeSH), "vírus papiloma humano", "human papilloma virus" (MeSH), "abuso sexual", "sexual abuse" (MeSH), and "transmissão", "transmission" (MeSH). Ethical and legal aspects were consulted in the Declaration and Convention on the Rights of Children and the World Health Organization. In addition, studies and reports cited by the literature and found in the database search were analyzed.

In this study, emphasis was given to children aged 12 years or younger to cover children of prepubertal age.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results and discussion of this review are subdivided into the following sections: Biology of the human papillomavirus, Epidemiology, Transmission, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, Therapeutics, Prognosis, Prevention, and Approach to the Child with AWs.

Biology of the human papillomavirus

HPV belongs to the family Papillomaviridae.7,8 This virus consists of an icosahedral capsid with 72 capsomeres and a double-stranded DNA molecule. HPV does not contain a lipoprotein envelope. The genome is divided into two regions: early (E), which encodes the proteins that are produced initially, and late (L), which encodes the proteins that are produced after the synthesis of the proteins of the E region. These two regions represent 45% and 40% of the viral genome, respectively, and contain the open reading frames E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, E7, L1, and L2.9,10 The non-coding region, designated long control region (LCR) or upstream regulatory region (URR), represents 15% of the viral genome and is involved in the control of viral gene expression.10

Approximately 200 different types of HPV have been identified; of these, approximately 30 to 40 types specifically infect the genital tract.7-10 The genital types of HPV are divided into high- and low-risk depending on their potential to cause anogenital neoplasms, particularly in the cervix. Low-risk oncogenic HPV types, such as types 6 and 11, are the primary causes of AWs, whereas high-risk oncogenic HPV types, such as types 16 and 18, are usually associated with cervical neoplasms.1 Common warts (verruca vulgaris) are caused by several types of HPV, but most often by HPV types 1 to 4.1 The tropism of a particular HPV type to specific regions of the cutaneous or mucosal tegument is known, although this tropism is not absolute (Table 1).7,8,11 Certain viral subtypes are usually found in specific locations, but overlap is common, particularly in the pediatric population. High-risk HPV types 16 and 18 and cutaneous HPV types 1 to 4, among others, can also be identified in AWs.

Table 1.

Clinical manifestations of different types of HPV*

| Skin lesions | |

| Common warts | 2, 4, 57 |

| Flat warts | 3, 10 (26-29 and 41) |

| Plantar warts | 1, 2, 4 |

| Epidermodysplasia verruciformis | 3, 5, 8, 9,10, 14,17,20-25 |

| Mucosal lesions | |

| Anogenital warts | 6, 11 (40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, 72, 81, 89) |

| Pre-malignant and malignant anogenital lesions | 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52,56, 58, 59 |

| 68, 73, 26, 53, 64, 65, 66, 67, 69, 70, 73, 82 | |

| Lesions in the oral cavity | 2, 6, 7, 11, 16, 18, 32, 57, 6, 11 |

| Oral papilloma | 13, 32 |

| Focal hyperplasia | 16 (18) |

| Oropharyngeal carcinoma | |

| Laryngeal lesions | 6,11 |

| Lesions of the conjunctiva | 11 |

Epidemiology

The incidence of AWs in children has increased, which may be reflected in the concomitant increase in adults, an increased awareness of the diagnosis of AWs in the general and pediatric population, and increased development and investment in vaccines against HPV.1,2,6 Girls are more frequently affected than boys, at a ratio of 3:1.7.1 However, little is known about the epidemiology of the virus in the pediatric population.12

A recent review has shown that the sexual abuse of minors is highly prevalent worldwide, with prevalence rates of 8-31% for girls aged less than 18 years and 3-17% for boys in the same age group, and that 9 out of 100 girls and 3 out of 100 boys are victims of forced sex.13 Sexual abuse accounts for approximately 10% of official cases of child maltreatment in the United States.14 Several studies have concluded that 80% to 90% of the abused children are girls, with a mean age of 7 to 8 years, and that 75% to 85% of children have been abused by a male aggressor known to the child and, above all, by family members, with several episodes of abuse over time. Other studies reported that 20% to 50% of the cases of sexual abuse involving children and adolescents are committed by minors.16.

The identification of AWs in children often raises suspicions of sexual abuse. In children with AWs, the reports of sexual abuse range from 0 to 80%.1,2,9,17,18 The association with sexual abuse increases with age; however, the age below which the hypothesis of sexual abuse can be excluded has not been defined.2,17 Sinclair et al. found that the likelihood of AWs due to sexual abuse was 37% in children aged 4 to 8 years and 70% in children older than 8 years.17 Another study concluded that children with AWs aged 4 years, 8 years, and more than 8 years had, respectively, 2-, 9-, and 12-fold increased likelihoods of having been sexually abused than children younger than 4 years.17

The prevalence of other STIs in sexually abused children with AWs varies, although it is usually low.19,20 Pandhi et al. observed that 14.2% of children with symptomatic STI also presented AWs.19

Transmission

The interpretation of HPV diagnosis in children as evidence of sexual abuse is controversial because little is known about the epidemiology of the virus in children, and other forms of transmission are possible. The main forms of transmission of HPV in children other than sexual transmission include vertical and horizontal transmission. Vertical transmission can be divided into three categories: (i) periconception transmission (period close to fertilization), (ii) prenatal transmission (during pregnancy), and (iii) perinatal transmission (during and immediately after birth). Therefore, the detailed gynecological history of the mother, including episodes of AWs and abnormal cytological examinations, is crucial.6 Vertical transmission is estimated to occur in approximately 20% of cases.6 Periconception transmission can theoretically occur via infected oocytes or spermatozoa.6 Although studies have detected HPV DNA in samples of sperm and sperm cells and in biopsy specimens of the vas deferens and upper female genital tract, it is still controversial whether these cases indicate true forms of transmission in clinical practice.21-23 In addition, no studies have evaluated the presence of HPV in oocytes.23 Some authors argue that the viral contamination of embryos may occur immediately after fertilization.6 The detection of HPV DNA in amniotic fluid, fetal membranes, umbilical cord blood, and placental trophoblastic cells suggests in utero infection, i.e., prenatal transmission.24,25 Perinatal transmission may occur during childbirth by the direct contact with the infected genital tract of the mother.6 Furthermore, there is evidence that the mothers who transmitted the infection by perinatal transmission had a significantly higher viral load in the cervix than those who did not transmit it.26 The frequent detection of HPV DNA in children a few days after birth may also be associated with transient mucosal colonization.27

Horizontal transmission may occur by autoinoculation or heteroinoculation.6 Autoinoculation refers to the contamination of a body site that was not infected by an infected body site.28,29 Heteroinoculation involves transmission by third parties, particularly by the parents or caregivers of the child, by direct contact.8 Transmission via fomites, including the sharing of personal hygiene products, bathing, or even underwear, is suggested but appears to have little impact on the development of active infections.9,30

Pathophysiology

HPV infection can be asymptomatic, transient, or characterized by epithelial proliferation, commonly known as warts. HPV primarily infects the differentiated squamous cellular epithelium, and basal keratinocytes are the target sites on the skin and mucous membranes. The virus remains in the nucleus as a double-stranded DNA episome.10 HPV can remain in a latent phase, and the incubation period after infection may last several months. Therefore, lesions may not become clinically evident for months to years after the initial exposure. This unpredictable latent period makes determination of the mode of transmission problematic.

The genome of HPV contains the proteins E1 and E2, which bind to DNA, promote its replication, and activate messenger RNA (mRNA) synthesis to allow its integration into the host genome.31 The E5 oncoprotein activates the epidermal growth factor receptor and promotes cell growth by increasing cell sensitization to growth signals. The E4 oncoprotein leads to cytokeratin breakdown. The oncogenes E6 and E7 encode oncoproteins that target the p53 and Rb proteins, which are encoded by tumor-suppressor genes.31 The genes E6 and E7 induce cell division and prevent apoptosis by binding to p53 and Rb, respectively, which are degraded and inactivated. This mechanism causes genetic instability, with unregulated cell replication and accumulation of aberrant chromosomal mutations, which cause dysplasia of varying degrees. The lesions may evolve into invasive carcinomas if left untreated.31-33

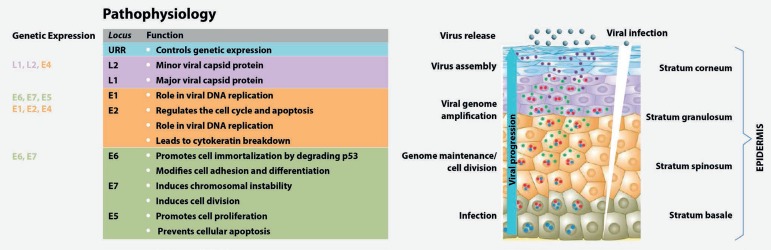

The proteins encoded by the viral E genes stimulate cell proliferation, which facilitates replication of the viral genome by the host cell DNA polymerase as the cells divide.10 The warts grow via a virally induced increase in cell number, leading to the thickening of the basal, spinous, and granular layers of the epidermis (Figure 1). Utilizing the keratinization process, the virus crosses the skin layers and is released with dead cells from the upper layer.10 The average period of wart development is 3 to 4 months.31 A good cellular and innate immune response is fundamental for the control and resolution of infections via activation of inflammatory responses. The persistence of infection increases the risk of malignancies, which are usually caused by high-risk oncogenic HPV.7,16

Figure 1.

HPV life cycle and gene function. Adapted from Bravo, et al.33(2015) and Lazarczyk, et al.32(2009).Genes with the same functions are indicated by the same colors

Clinical Manifestations

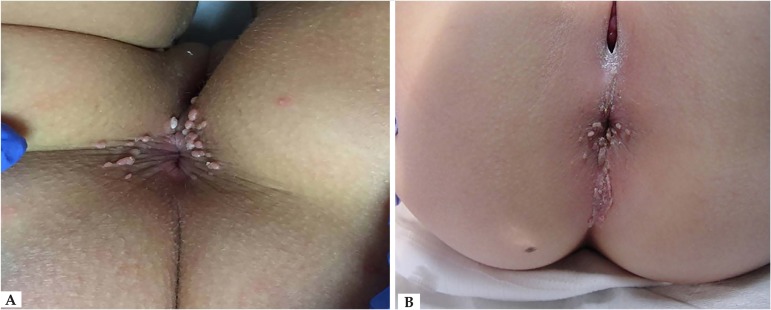

HPV infections are associated with benign lesions, such as genital warts, and malignant lesions, such as anogenital, head and neck neoplasms. The clinical manifestations of anogenital HPV infection depend on host characteristics, HPV genotype, characteristics of the infected epithelia, and environmental factors.33 Most anogenital HPV infections are subclinical. The virus is usually found in apparently healthy skin and mucous membranes, suggesting a commensalism/mutualism relationship between HPV and the host cell.33,34 The most common type of infection is in the form of self-limited proliferations of the skin and mucous membranes, which usually regress with time. The appearance of warts depends on the type of HPV and the infected site.31 The warts usually appear as skin-colored verrucous papules approximately 1 to 5mm in diameter (Figure 2). They can be pedicled, and, if extremely exophytic, they may have a cauliflower-like appearance. Giant tumor masses that occupy the anogenital area are known as Buschke-Lowenstein tumors (Figure 3). Warts are usually asymptomatic; however, they may bleed, become painful, or pruritic.1 In prepubertal boys, the region most frequently affected by AWs is the perianal region. In girls, the preferred location is the perianal and vulvar region, regardless of the occurrence of sexual abuse.1

Figure 2.

A) Perianal anogenital warts in a female child. B) Perianal anogenital warts in the intergluteal fold of a female child

Figure 3.

Buschke-Lowenstein tumor in a female child with malaria

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of AWs is primarily clinical, but it may be aided by magnification instruments, such as a colposcope, together with the application of acetic acid or dyes, such as lugol.1,35 Biopsy and histological examination should be conducted in case of doubt.35 In addition, colposcopy seems to increase the diagnostic sensitivity for minimal genital traumas resulting from sexual abuse, which would be difficult to identify during physical examination; therefore, it is useful for gathering evidence in cases of sexual abuse.

HPV cannot be cultured; thus, all of the HPV diagnostic methods used to date rely on viral DNA detection. Molecular biology methods, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and hybrid capture, can detect genomic HPV sequences in different lesions produced by the virus, thus enabling the screening of genetic material in epithelial cells and genotyping. The execution of PCR assays allows the amplification of specific DNA sequences. Real-time PCR, in contrast to the traditional method, consists of monitoring the DNA amplification process as it occurs. Hybrid capture is based on liquid-phase hybridization using synthetic RNA probes complementary to the genome sequences of 13 high-risk and 5 low-risk HPV types, allowing the differentiation of two groups of viruses (high- and low-risk) and the viral load.36 At present, DNA detection is an established tool for the diagnosis and monitoring of HPV-related diseases. However, there is still a need for a reference method.37

The genotyping of HPV DNA in children and adolescents suspected of sexual abuse without clinical evidence of AWs is discouraged because the infection is transient and the virus is eliminated by a healthy immune system, and it appears that a few specific genital HPV types are associated with sexual abuse.18 However, no consistent evidence has been established between the type of HPV and the mode of transmission, and additional research is needed to elucidate this association.2,11

Serological tests with the detection of anti-HPV antibodies are not routine. These tests are used for epidemiological studies and do not represent a valid diagnostic test in clinical practice. In addition to the low sensitivity and specificity of these tests, the use of serology as a possible marker of HPV infection has led to considerable difficulties because of the occurrence of cross-reactions between the different types of HPV and the poor responses of immunocompetent cells in epithelial layers, where viral expression occurs.10

Therapeutics

Most AWs disappear spontaneously within a few months or years in children with healthy immune systems.27 Therefore, active non-intervention is an option in children with asymptomatic lesions. However, studies suggest that lesions should be actively treated in cases in which they persist for more than 2 years or are symptomatic.

Treatments can be divided into surgical and non-surgical methods. Surgical methods involve the non-specific elimination of infected tissue, including cryotherapy, CO2 laser therapy, pulsed-light therapy, electrocoagulation, and surgical excision. These procedures often require local or general anesthesia.1

Most studies were conducted in the adult population using different treatment strategies, and efficacy data are extrapolated to the pediatric population. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen is the most commonly used surgical method for the treatment of warts. In the adult population, the cure rate ranges from 62% to 86%.1 However, no studies have been conducted in the pediatric population. CO2 laser is a safe method, and the cure rate in the adult population varies from 27% to 100%.1,6 Electrocoagulation is another non-specific destruction method, and the healing rate in the adult population ranges from 57% to 94%. Pulsed-light therapy is a less commonly used option but, in a series of 22 patients, the cure rate was 100%, with little postoperative pain, which makes this technique an attractive option for children with AWs.1

Surgical excision is also an option for patients with few lesions or single large lesions.1,6,38-40 With regard to medical treatments, imiquimod at 5% was approved for treatment in children aged 12 years or older and is the first-line treatment of AWs in children in this age group.1,41 This synthetic immunomodulator activates cellular and innate immune responses via cytokine activation. Although the clinical treatment of AWs for children younger than 12 years has not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration, several studies have reported the efficacy of this drug in children as young as 6 months of age, with cure rates of up to 75%.1 Keratolytic agents such as salicylic acid are sometimes used in the treatment of HPV lesions. Drugs with antimitotic properties, including podophyllotoxin, podophyllin, and 5-fluoracyl, are also available for the treatment of vaginal infections but have not been approved for the pediatric population.40

Although they represent a benign pathology, condylomas are a cause of anxiety and involve the use of many human and financial resources.36,37 There is no single treatment for this condition. Multiple sessions and combinations of different techniques and treatments are usually required to achieve healing.

Prognosis

The viral infection is usually localized and regresses spontaneously, possibly because of the immune response, and may recur. In healthy children, approximately 70% of the AWs resolve spontaneously within 1 year, and 90% resolve within 2 years.27 Immunocompromised patients have higher numbers of recurrences and aggressive infections and a lower probability of spontaneous remission.10

The identification of HPV types known to have a unique oncogenic potential (e.g., types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 52, 55, 56, and 58) entails a long follow-up of children infected with these viral types. Pre-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions have been reported in small children and older patients.2 Anogenital HPV infections may predispose the child to the development of genital neoplasms in the future, but the follow-up period has not been defined in these cases. Cervical cancer is recognized as an STI and is the second most common malignant disease in women worldwide.10 High-risk HPV types 16, 18, 31, and 45 represent 80% of the positive cases of cancer, and type 16 has the highest incidence.10 Although HPV appears to be necessary for the development of cervical cancer, the onset of cancer is not certain in the presence of a viral infection. Infections progress to cancer in only a small number of cases, and progression depends on many factors, including the persistence of infection, viral load, and the integration of high-risk HPV DNA into the host genome.10

The possible progression of AWs after immunosuppression or acute infection with the varicella virus has been reported and indicates the need for immunization with the varicella vaccine in children with HPV.2

Prevention

Most cell damage during viral infection occurs at an early stage of infection and often before the development of clinical symptoms, which limits treatment. For this reason, prevention, in addition to being less expensive, is considered the best method. Primary prevention relies on two approaches: public and personal hygiene and vaccination, which uses the immune system to combat viral infection. Primary prevention measures can reduce HPV infections, including persistent infections, low-grade intra-epithelial lesions, and precursor lesions of cervical cancer. Primary prevention measures can also reduce AWs and recurrent laryngeal papillomatosis.

Secondary prevention aims at the early detection of pre-malignant and malignant lesions via screening programs.42 HPV is located in the epithelial layer and thus, has minimal contact with the immune system of the host. The immune response is usually mild and transient. The HPV vaccine has been used to counteract this mild immune response.10 The currently available vaccines are the bivalent vaccine (Cervarix®) against HPV 16 and 18 (responsible for 70% to 75% of cases of cervical cancer) and (Gardasil®) against HPV 6 and 11 (responsible for approximately 90% of cases of AWs) in addition to HPV 16 and 18.40,42 In several countries, one of these vaccines is included in the national vaccination plan. The most recent non-invasive vaccine (Gardasil 9®) also targets five other genotypes (HPV 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), in addition to the four previously mentioned genotypes, and aims to prevent the development of AWs and infection with the genotypes responsible for most anogenital cancers.32,40 Vaccines are prophylactic and prevent infection by the virus. These vaccines have the following characteristics: contain non-infectious virus-like particles, are produced by recombinant DNA technology, and function by stimulating the production of antibodies specific for the targeted HPV types. The duration of immunity conferred by vaccination is unknown. Protection against infection depends on the antibody titer produced by the vaccinated subject, the presence of antibodies at the site of infection, and their persistence over time.10,42 However, vaccination is not a substitute for routine cervical examinations because no vaccine is completely effective, and the vaccines only prevent infections with the HPV subtypes included in the vaccine composition, although cross-reactions with other HPV types have been documented.41

Vaccination should preferably be administered to adolescents before sexual initiation.41 Recent studies have reported the occurrence of several subclinical high-risk HPV infections in the prepuce of boys, a region that is considered a large reservoir for viral diseases and has not received enough attention to date.43 These results support the interest in the vaccination against HPV in male subjects.44 Tetravalent and nonavalent vaccines are recommended to males starting at ages 11 to 12 years and may be administered until the age of 26, as in females.41

In sexually abused children, the administration of HPV vaccines is recommended at age 9.

Approach To Children With Aws

AWs in childhood need to be addressed by a multidisciplinary approach to both the child and the family. A detailed clinical history of the child and caregivers is essential. The importance of the diagnosis of anogenital or non-genital warts in caregivers and a history of HPV infection of the cervix in the mother should be emphasized. Moreover, a complete physical examination is mandatory, including careful evaluation of the genitals and anus. The diagnosis of AWs should include the evaluation of their precise location, color, shape/appearance, texture, borders, number and arrangement of lesions (solitary or clustered), accompanying symptoms (burning sensation, pruritus, bleeding, pain) and, if necessary, the performance of biopsies on atypical or persistent lesions to exclude other conditions.

Findings compatible with sexual abuse include hymen rupture, enlargement of the transverse diameter of the hymen, vaginal/penile or anal pain, vaginal/penile or anal bleeding, vaginal/penile discharge, urinary infections (particularly recurrent), fissures, lacerations, bruises, enuresis, encopresis, headaches, and abdominal pain. The anal sphincter should also be examined.

Other STIs in sexually abused children should be excluded, which is why serological screenings for syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B and C and screening for gonococcal and Chlamydia trachomatis infections in the anogenital exudate should be conducted. 20 The family practitioner or pediatrician who cares for the child with AWs should rely on the specialist evaluation of the dermatologist. Gynecological and urological approaches are also justified. In addition, psychological and social assessments, including the evaluation of social risk factors, should be performed. Any change in the child's behavior should be evaluated.36 The support of the psychologist and/or child psychiatrist is fundamental to this approach.

Identifying cases of sexual abuse is difficult given the various routes of HPV transmission, its long period of latency after infection (approximately 3 months in adolescents and adults, unknown in children), and the fact that HPV genotyping does not elucidate its mode of transmission. Most sexually abused children have no identifiable lesions, or these lesions are completely healed before clinical evaluation.9 The physical findings during anogenital examination in approximately 60% of children with STIs are unremarkable or non-specific.35,45 Therefore, the period from sexual abuse to clinical examination by the specialist is critical. Furthermore, an urgent evaluation is crucial in cases in which sexual abuse is suspected.46

Considering that one of the main obstacles is the lack of knowledge of the anatomy of the female genitalia before menarche, the implementation of standardized approaches and training of health professionals are necessary to evaluate potential victims of sexual abuse, ensuring a high level of accuracy in these assessments.45,46 Studies have shown that the rate of diagnosis of sexual abuse by the combination of medical and social assessments reached 22% and increased to 71% when an interdisciplinary investigation was used.35

The prevalence of cases of abuse is underestimated because there are few complaints and cases that actually go to court, especially when they involve intrafamily abuse and high socioeconomic status where these cases are more easily hidden. Furthermore, children do not have adequate communication skills to report these events or to provide details, cannot recognize the action as inappropriate, and repress unpleasant memories.45 Most investigated cases involve, as a rule, abusers with lower socioeconomic status, and these social groups have higher prevalence rates of teenage pregnancy, drug abuse, poverty, unemployment, prostitution, and promiscuity, i.e., contexts that promote dysfunctional behaviors.2

CONCLUSION

The presence of AWs or only HPV DNA in the genital region, without collection of clinical information and determination of the social context, is not a diagnostic criterion of sexual abuse. It should be noted that the age below which the hypothesis of sexual abuse can be excluded has not been defined. However, in children younger than 4 years, the non-sexual transmission of HPV should be strongly considered as long as there is no other concomitant STI, history of sexual abuse, evidence of genital trauma, or hymen rupture.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to assess with certainty the origin of HPV infection in children with AWs because neither HPV genotyping nor the infection's clinical features allow the identification of the mode of transmission as sexual or otherwise. Several studies indicate that the origin of AWs usually remains hidden, with no indication of sexual abuse.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

This study was conducted at the Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Centro Hospitalar São João, EPE, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto - Porto, Portugal.

Financial support: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Culton DA, Morrell DS, Burkhart CN. The Management of Condyloma Acuminata in the Pediatric Population. Pediatr Ann. 2009;38:368–372. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20090622-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcoux D, Nadeau K, McCuaig C, Powell J, Oligny LL. Pediatric anogenital warts: a 7-year review of children referred to a tertiary-care hospital in Montreal, Canada. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:199–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Who.int Organización Mundial de la Salud. Maltrato Infantil. 2014. [04 Maio 2016]. Internet. Disponible: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs150/es/

- 4.Albuquerque C. Documentação e Direito Comparado. nº 83/84. Lisboa: Oct, 2001. Declaração dos Direitos das Crianças "As Nações Unidas, a Convenção e o Comité". [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brasil . Decreto no 99.710, de 21 de novembro de 1990. Convenção sobre os Direitos das Crianças. Diário Oficial da União; Nov 22, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Syrjänen S. Current concepts on human papillomavirus infections in children. APMIS. 2010;118:494–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2010.02620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cubie HA. Diseases associated with human papillomavirus infection. Virology. 2013;445:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doorbar J, Quint W, Banks L, Bravo IG, Stoler M, Broker TR, et al. The biology and life-cycle of human papillomaviruses. Vaccine. 2012;30:F55–F70. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jayasinghe Y, Garland SM. Genital warts in children: what do they mean? Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:696–700. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.092080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martins PP, Pereira JM. Métodos de diagnóstico da infecção pelo vírus do papiloma humano. Lisboa: Universidade de Lisboa; 2013. tese. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syrjanen S. HPV infections in children. Papillomavirus Report. 2003;14:93–110. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel H, Wagner M, Singhal P, Kothari S. Systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of genital warts. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:39–39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barth J, Bermetz L, Heim E, Trelle S, Tonia T. The current prevalence of child sexual abuse worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2013;58:469–483. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0426-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Putnam FW. Ten-year research update review: child sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:269–278. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammerschlag MR. Sexually transmitted diseases in sexually abused children: medical and legal implications. Sex Transm Infect. 1998;74:167–174. doi: 10.1136/sti.74.3.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barroso RG, Manita C, Nobre C. Violência sexual juvenil: conceptualização, caracterização e prevalência. RPCC. 2011;21:430–430. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinclair KA, Woods CR, Kirse DJ, Sinal SH. Anogenital and respiratory tract human papillomavirus infections among children: age, gender, and potential transmission through sexual abuse. Pediatrics. 2005;116:815–825. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogstad KE, Wilkinson D, Robinson A. Sexually transmitted infections in children as a marker of child sexual abuse and direction of future research. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2016;29:41–44. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandhi D, Kumar S, Reddy BS. Sexually transmitted diseases in children. J Dermatol. 2003;30:314–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glaser JB, Hammerschlag MR, McCormack WM. Epidemiology of sexually transmitted diseases in rape victims. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:246–254. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pakendorf UW, Bornman MS, Du Plessis DJ. Prevalence of human papilloma virus in men attending the infertility clinic. Andrologia. 1998;30:11–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1998.tb01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rintala MA, Pöllänen PP, Nikkanen VP, Grénman SE, Syrjänen SM. Human papillomavirus DNA is found in the vas deferens. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1664–1667. doi: 10.1086/340421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fedrizzi EN, Villa LL, de Souza IV, Sebastião AP, Urbanetz AA, De Carvalho NS. Does human papillomavirus play a role in endometrial carcinogenesis? Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009;28:322–327. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e318199943b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eppel W, Worda C, Frigo P, Ulm M, Kucera E, Czerwenka K. Human papillomavirus in the cervix and placenta. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:337–341. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00953-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arena S, Marconi M, Ubertosi M, Frega A, Arena G, Villani C. HPV and pregnancy: diagnostic methods, transmission and evolution. Minerva Ginecol. 2002;54:225–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bodaghi S, Wood LV, Roby G, Ryder C, Steinberg SM, Zheng ZM. Could human papillomaviruses be spread through blood? J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5428–5434. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5428-5434.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richardson H, Kelsall G, Tellier P, Voyer H, Abrahamowicz M, Ferenczy A, et al. The natural history of type-specific human papillomavirus infections in female university students. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:485–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos-López G, Márquez-Domínguez L, Reyes-Leyva J, Vallejo-Ruiz V. General aspects of structure, classification and replication of human papillomavirus. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2015;53(Suppl 2):S166–S171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Syrjänen S, Puranen M. Human papillomavirus infections in children: the potential role of maternal transmission. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2000;11:259–274. doi: 10.1177/10454411000110020801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinclair KA, Woods CR, Sinal SH. Venereal warts in children. Pediatr Rev. 2011 Mar;32:115–121. doi: 10.1542/pir.32-3-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray PR, Ks Rosenthal, Pfaller MA. Papillomaviruses and Polyomaviruses. In: Murray PR, Ks Rosenthal, Pfaller MA, editors. Medical Microbiology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Sounders; 2013. pp. 445–450. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lazarczyk M, Cassonnet P, Pons C, Jacob Y, Favre M. The EVER proteins as a natural barrier against papillomaviruses: a new insight into the pathogenesis of human papillomavirus infections. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:348–370. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00033-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bravo IG, Félez-Sánchez M. Papillomaviruses: Viral evolution, cancer and evolutionary medicine. Evol Med Public Health. 2015;2015:32–51. doi: 10.1093/emph/eov003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spginecologia.pt . Sociedade Portuguesa de Ginecologia. Vacina contra o HPV. Reunião de Consenso Nacional. Sociedade Portuguesa de Ginecologia. Coimbra, Portugal: Fev-Jul. 2007. [maio 2016]. Internet. Disponível em: http://www.spginecologia.pt/uploads/reuniao_de_consenso_nac._net.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drezett J, Vasconcellos RM, Pedroso D, Blake MT, Oliveira AG, Abreu LZ. Transmission of anogenital warts in children and association with sexual abuse. Rev Bras Crescimento Desenvolv Hum. 2012;22:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stefanaki C, Barkas G, Valari M, Bethimoutis G, Nicolaidou E, Vosynioti V, et al. Condylomata acuminata in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:422–424. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318245a589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ecdc.europa.eu . European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Guidance for the Introduction of HPV Vaccines in EU Countries. Stockholm: Jan, 2008. [2016 May 04]. Internet. updated January 2008. Available from: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/0801_GUI_Introduction_of_HPV_Vaccines_in_EU.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cook K, Brownell I. Treatments for genital warts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:801–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park HS, Choi WS. Pulsed dye laser treatment for viral warts: a study of 120 patients. J Dermatol. 2008;35:491–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2008.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lacey CJ, Goodall RL, Tennvall GR, Maw R, Kinghorn GR, Fisk PG, et al. Randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of podophyllotoxin solution, podophyllotoxin cream, and podophyllin in the treatment of genital warts. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:270–275. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.4.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Chesson HW, Curtis CR, Gee J, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dgs.pt Programa Nacional de Vacinação (PNV) Introdução da vacina contra infecções por Vírus do Papiloma Humano 2008. Texto de apoio à Circular Normativa nº 22/DSCS/DPCD. [04 Maio 2016]. Internet. Disponível em: http://www.dgs.pt/directrizes-da-dgs/normas-e-circulares-normativas/-circular-normativa-n-22dscsdpcd-de-17102008.aspx.

- 43.Balci M, Tuncel A, Baran I, Guzel O, Keten T, Aksu N, et al. High-risk Oncogenic Human Papilloma Virus Infection of the Foreskin and Microbiology of Smegma in Prepubertal Boys. Urology. 2015;86:368–372. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Martino M, Haitel A, Wrba F, Schatzl G, Klatte T, Waldert M. High-risk human papilloma virus infection of the foreskin in asymptomatic boys. Urology. 2013;81:869–872. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson CF. Child sexual abuse. Lancet. 2004;364:462–470. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16771-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adams JA. Guidelines for medical care of children evaluated for suspected sexual abuse: an update for 2008. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20:435–441. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32830866f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]