Abstract

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a global health problem. Several studies have implicated genetic host factors in predisposing populations to TB disease. In this study, we have selected NSMAF (Neutral Sphingomyelinase Activation Associated Factor) as a candidate gene to evaluate its level of association with TB disease in a Moroccan population for two reasons: first, this gene is located in a major susceptibility locus on chromosomal region 8q12-q13 in the Moroccan population, closely linked to the CYP7A1 gene, which was previously shown to be associated with TB disease; second, NSMAF has an important role in immune system function.

Methods

We conducted a case-control study including 269 genomic DNA samples extracted from pulmonary TB (PTB) patients and healthy controls (HC). We genotyped three selected SNPs (rs2228505, rs36067275 and rs10505004) using TaqMan® allelic discrimination assays.

Results

Only the rs1050504 C > T genotype was observed to be significantly associated with an increased risk for developing pulmonary TB (41.8% vs 27%, OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.16–3.27; p = 0.01). In contrast, the TT genotype was significantly associated with resistance to PTB (4.1% vs 15.6%, OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.08–0.63; p = 0.002).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that genetic variations in the NSMAF gene could modulate the risk of PTB development in a Moroccan population. Further functional studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, NSMAF, Moroccan, Apoptosis

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the oldest infectious diseases that is still a serious health challenge in the developing world. According to a recent report published by the World Health Organization, TB killed 1.5 million people in 2015 [1]. In Morocco, the Ministry of Health registered high incidence in 2015, reaching 89 new cases per 100,000 inhabitants [2].

TB is a multifactorial disease, and thus, identifying host genes that determine its susceptibility is far from an easy task. For this reason, candidate gene studies are receiving increasing attention in genetic epidemiology. This method begins with the selection of a putative candidate gene followed by the selection of genetic polymorphisms based on its predicted function. Hence, by focusing directly on genetic variations within a gene of interest, this approach offers considerable advantages in terms of detecting disease-associated genes [3–5].

In the Moroccan population, a few studies have been conducted in this context, with some reporting a significant association between TB disease and genetic variants in MIF, PTPN22, VDR, CYP7A1 and STAT4 [6–10]. Furthermore, it seems that the major susceptibility locus for TB in the Moroccan population is located on chromosomal region 8q12-q13 [11].

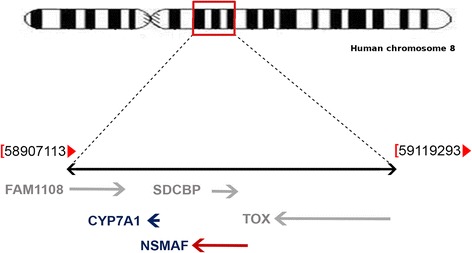

Two genetic variants associated with TB have been identified. The first one is rs3808607 in the CYP7A1 gene, and the second is rs1568952, located 6 kb downstream of the last TOX gene exon. The NSMAF gene is located [12] between the CYP7A1 and TOX genes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A representative scheme showing the localization of the NSMAF gene in the chromosome 8 (modified from [13]). At the chromosomal region 8q12.13 from 58,907,113 to 59,119,293 bp, NSMAF gene is closely located between CYP7A1 and TOX gene

The NSMAF (Neutral Sphingomyelinase Activation Associated Factor) gene encodes for the protein NSMAF or FAN (factor associated with neutral sphingomyelinase activation) [14]. NSMAF is a 140 KDa WD-repeat protein composed of 917 aa [15, 16]. This protein interacts specifically with the cytoplasmic sphingomyelinase activation domain of the 55kD tumour necrosis factor receptor, known as Tumour Necrosis Factor Receptor Type I (TNFRI) or p55(CD120a), also called NSD (neutral sphingomyelinase domain). Indeed, the FAN protein is an essential component of the activation of TNF-α induced neutral sphingomyelinase 2 and 3 [17, 18], leading to activation of the sphingomyelin-ceramide pathway. In fact, this biological event is initiated by the hydrolysis of sphingomyelin to ceramide, the lipid second messenger implicated in cell signalling [19].

In addition, with stable expression of a dominant-negative form of FAN in human fibroblasts, caspase activation and cytochrome c release from mitochondria are reduced, and the TNF-α-triggered apoptosis is obviously inhibited [20]. Furthermore, FAN contributes to the inflammation process and is required for full expression of the genes encoding CXCL2 and IL-6 [21]. Overexpression of FAN in rat cardiomyocytes was shown to lead to increased cell death [22]. Interestingly, NSMAF is also associated with multiple sclerosis [23, 24], and one study demonstrated that FAN can promote melanoma cellular motility and tumour invasiveness in an in vivo model [25].

Taking all these findings together, there are several lines of evidence to support the possible involvement of NSMAF in TB development; therefore, it could be postulated as a candidate gene of susceptibility in TB disease. The aim of this work is to evaluate the impact of selected NSMAF polymorphisms on TB susceptibility in the Moroccan population.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a case–control study in the Moroccan population. 10 ml of peripheral blood was collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes from all participants recruited over the course of 2 years. The blood samples were collected from 19 health centres comprising the Centres of TB Treatment and Respiratory Disease (CTRD) and the university hospitals for PTB patients. Patients were evaluated by microbiological diagnosis, physical examination and chest X-rays; all patients were smear positive for acid-fast bacilli and mycobacterial culture and were tuberculin skin test positive. HC group consisted of healthy donors with no signs, symptoms or history of previous tuberculosis. They were tuberculin skin negative and remained in this immunological status during the 2 years after recruitment in a posterior telephonic “check-contact”. The recruitment was done from the Regional Centers of Blood Transfusion (RCBT) of five different regions of Morocco (Oujda, Fez, Tangier, Rabat, and Marrakech). All subjects were negatives for HIV-1/2 infection (tested by Axsym Assays, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA). This study was approved by the local ethics committee (faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Mohammed V University of Rabat, as reference number 1169), and informed written consent was obtained from all subjects. Structured questionnaires were used to collect medical history data, biological investigations and demographic parameters (Table 1 ). The questionnaire analyses show that the sex ratio (males /females) among TB patients was almost similar to that of the HC group (2.76 vs 2.52, respectively). The mean age ± standard deviation was 33.43 (±13.24) years, ranging from 18 to 67 years, and 32.41 (±11.10) years, ranging from 18 to 61 years, for patients and HC, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of tuberculosis patients and healthy controls

| Variables | TB patients N = 128 | Healthy controls N = 141 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean age ± SD) | 33,43 ± 13.24 | 32.41 ± 11.10 | ||

| Gender [n (%)] | ||||

| Men | 94 | 73.4% | 101 | 71.6% |

| Women | 34 | 26.6% | 40 | 28.4% |

| Clinical feature | ||||

| Hemoptysis | 55/128 | 43% | ||

| Expectoration | 117/128 | 91% | ||

| Fever | 112/128 | 87% | ||

| Cough | 125/128 | 98% | ||

| weight loss | 122/128 | 95% | ||

| Abnormality shown by chest X-ray examination | 128/128 | 100% | ||

NSMAF genotyping

DNA extraction: Total genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood of all TB patients and HC using a QIAampDNA Blood Maxi kit (QIAamp® DNA Blood Mini Kit, Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and was stored at −20 °C until use.

NSMAF selected SNPs: Three SNPs of the NSMAF gene were selected for genotyping. The first SNP, rs36067275 C > T, is a missense mutation causing a substitution of glutamic acid by lysine at 487. The second SNP, rs2228505 T > C, is a missense mutation causing a substitution of tyrosine by cysteine at position 626. The third is located in the 3′ UTR (untranslated region) represented by rs1050504 C > T.

Real time PCR genotyping: The three selected SNPs were genotyped by Real time PCR technology using a TaqMan® Genotyping Assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Reactions were performed as recommended by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems). PCR allelic discrimination was performed on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), which measured the specific allele fluorescence of each sample. Impaired samples were genotyped twice.

Statistical analysis

Allele and genotype frequencies between PTB patient and HC were determined by direct counting and were compared afterward using the χ2-test. Patients and controls were tested for conformity to Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. All statistical analyses were performed using EPI INFOTM, version 7.1.0.6 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA; 08 September 2012). We considered the results with corresponding p-values below 0.05 to be statistically significant. Moreover, the odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated to evaluate the risk of association between genotypes or alleles and TB disease.

To estimate the haplotype frequencies, the program CubEX was used [26]. This program is also able to provide the normalized linkage disequilibrium (LD) parameter (D’) and the LD correlation coefficient between two loci (r2).

Results

All genotype frequencies of patients and HC were consistent with respect to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

There were no significant differences between patients and HC in the distribution of genotypes and allele frequencies for either rs36067275 C/T or rs2228505 T/C SNPs (Table 2). Nevertheless, despite the significant difference not being reached for allele distribution between the groups for rs2228505 T/C SNP, the mutant allele C was more frequent in patients than in controls (14.06% in patients versus 9.32% in controls, p = 0.1, OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 0.9–2.79) (Table 3). However, a statistical analysis of genotype distribution for the rs1050504 polymorphism yielded an interesting result. A significant and positive association was found between the CT genotype and an increased risk of PTB development (41.8% vs 27%, OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.16–3.27; p = 0.01). Conversely, the TT genotype frequency was statistically more frequent in HC than in patients (15.6% vs 4.1%, OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.08–0.63; p = 0.002, respectively) (Table 4).

Table 2.

Genotypes and alleles frequencies for the rs36067275 polymorphism in pulmonary tuberculosis patients and healthy controls

| Patients vs Controls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs36067275 [C/T] | PTB N = 112 (%) | HC N = 116 (%) | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

| Genotypes (N) | ||||

| CC | 112(100) | 116(100) | > 0,05 | |

| CT | 0 | 0 | ||

| TT | 0 | 0 | ||

| Alleles (2 N) | ||||

| C | 224 (100) | 232 (100) | > 0,05 | |

| T | 0 | 0 | ||

CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio

Table 3.

Genotypes and alleles frequencies for the rs2228505 polymorphism in pulmonary tuberculosis patients and healthy controls

| Patients vs Controls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2228505 [T/C] | PTB N = 128 (%) | HC N = 118 (%) | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

| Genotypes (N) | ||||

| TT | 95 (74,2) | 96 (81,4) | 0,17 | 0,65 (0,35–1,21) |

| CT | 30 (23,4) | 22 (18,6) | 0,35 | 1,33 (0,72–2,47) |

| CC | 3 (2,4) | 0 | 0,09 | ND |

| Alleles (2 N) | ||||

| T | 220 (85,9) | 214 (90,7) | 0,1 | 0,62 (0,35–1,1) |

| C | 36 (14,1) | 22 (9,3) | 1,59 (0,9–2,79) | |

Table 4.

Genotypes and alleles frequencies of the rs1050504 polymorphism in pulmonary tuberculosis patients and healthy controls

| Patients vs Controls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1050504 [C/T] | PTB N = 122 (%) | HC N = 141 (%) | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

| Genotypes (N) | ||||

| CC | 66 (54.1) | 81 (57.4) | 0.58 | 0.87 (0.53–1.42) |

| CT | 51 (41.8) | 38 (27) | 0.01* | 1.95 (1.16–3.27) |

| TT | 5 (4.1) | 22 (15.6) | 0.002* | 0.23 (0.08–0.63) |

| Alleles (2 N) | ||||

| C | 183 (75) | 200 (70.9) | 0.29 | 1.23 (0.83–1.81) |

| T | 61 (25) | 82 (29.1) | ||

*Significant p-values appear in bold

✓ Stratification by sex and age

We also carried out the genetic analysis by sex and age stratification and evaluated the risk for TB development in subjects carrying each relevant genotype. We observed a significant difference in high frequency of the rs1050504 CT genotype in males, but not females, for PTB disease (42.2% vs 25.7%, OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.14–3.88; p = 0.01) (Table 5). In contrast, our data show that the TT genotype was more frequent in HC males than in PTB males (4.5% vs 18.8%, OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.06–0.62; p = 0.002) (Table 5). Additionally, when taking into consideration the age factor, statistical analysis revealed that the numbers of patients between ages 30 and 49 carrying the rs1050504 TT genotype were significantly fewer than their homologous subjects in the HC group (3.3% vs 6.8%, OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.06–0.82; p = 0.002) (Table 6).

Table 5.

Distribution by sex of allele and genotype frequencies of the rs1050504 and rs2228505 polymorphisms between pulmonary tuberculosis patients and healthy controls

| PTB patients | Controls | TB male vs healthy male | TB female vs healthy female | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (%) | F (%) | M (%) | F (%) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | |

| rs1050504 [C/T] | ||||||||

| Genotypes | n = 90 | n = 32 | n = 101 | n = 40 | ||||

| CC | 48 (53,3) | 18 (56,3) | 56 (55.5) | 25 (62.5) | 0,76 | 0,91 (0,51–1,62) | 0,59 | 0,77 (0,29–1,98) |

| CT | 38 (42,2) | 13 (40,6) | 26 (25.7) | 12 (30) | 0,01* | 2,1 (1,14–3,88) | 0,34 | 1,59 (0,6–4,24) |

| TT | 4 (4,5) | 1 (3,1) | 19 (18.8) | 3 (7.5) | 0,002* | 0,2 (0,06–0,62) | 0,42 | 0,39 (0,03–4,02) |

| Alleles | ||||||||

| C | 134(74,4) | 49 (76,6) | 138 (68,3) | 62 (77,5) | 0,16 | 1,37(0,87–2,14) | 0,89 | 0,94 (0,43–2,07) |

| T | 46 (25,6) | 15 (23,4) | 64 (31,7) | 18 (22,5) | ||||

| rs2228505 [T/C] | ||||||||

| Genotypes | n = 94 | n = 34 | n = 78 | n = 40 | ||||

| TT | 64 (68,1) | 31 (91,2) | 62 (79,5) | 34 (85) | 0,09 | 0,55 (0,27–1,1) | 0,41 | 1,82 (0,41–7,9) |

| CT | 27 (28,7) | 3 (8,8) | 16 (20,5) | 6 (15) | 0,21 | 1,56 (0,76–3,17) | 0,41 | 0,54 (0,12–2,38) |

| CC | 3 (3,2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,11 | ND | ND | ND |

| Alleles | ||||||||

| T | 155(82,4) | 65 (95,6) | 140 (89,7) | 74 (92,5) | 0,53 | 0,53 (0,28–1,01) | 0,43 | 1,75 (0,42–7,3) |

| C | 33 (17,6) | 3 (4,4) | 16 (10,3) | 6 (7,5) | ||||

ND not determined; *Significant p-values appear in bold

Table 6.

Distrubition by age of allele and genotype frequencies of the rs1050504 and rs2228505 polymorphisms between pulmonary tuberculosis patients and healthy controls

| ≤ 29 years | 30–49 years | ≥ 50 years | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTB (%) | Controls (%) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | PTB (%) | Controls (%) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | PTB (%) | Controls (%) | p-Value | OR (95%CI) | |

| rs1050504[C/T] | ||||||||||||

| Genotypes | n = 60 | n = 44 | n = 49 | n = 81 | n = 13 | n = 16 | ||||||

| CC | 31(51,7) | 29 (65,9) | 0,14 | 0,55(0,24–1,27) | 28 (57,1) | 43 (53,1) | 0,65 | 1,17 (0,57–2,4) | 8 (61,5) | 9 (56,2) | 0,91 | 1,08 (2,23–4,94) |

| CT | 27 (45) | 12 (27,3) | 0,06 | 2,18 (0,94–5,03) | 18 (36,8) | 20 (24,7) | 0,14 | 1,77 (0,82–3,82) | 5 (38,5) | 6 (37,5) | 0,82 | 1,19 (0,25–5,49) |

| TT | 2 (3,3) | 3 (6,8) | 0,41 | 0,47 (0,07–2,94) | 3 (6,1) | 18 (22,2) | 0,01* | 0,22 (0,06–0,82) | 0 | 1 (6,3) | 0,37 | ND |

| Alleles | ||||||||||||

| C | 89 (74,2) | 70 (79,5) | 0,36 | 0,73 (0,38–1,42) | 74 (75,5) | 106 (65,4) | 0,08 | 1,62 (0,92–2,85) | 19 (79,2) | 24 (75) | 0,71 | 1,26 (0,35–4,5) |

| T | 31 (25,8) | 18 (20,5) | 24 (24,5) | 56 (34,6) | 5 (20,8) | 8 (25) | ||||||

| rs2228505[T/C] | ||||||||||||

| Genotypes | n = 64 | n = 40 | n = 52 | n = 62 | n = 12 | n = 15 | ||||||

| TT | 47 (73,5) | 31 (77,5) | 0,64 | 0,80 (0,31–2,02) | 38 (73,1) | 52 (83,9) | 0,15 | 0,52 (0,20–1,30) | 10 (83,3) | 12 (80) | 0,82 | 1,25 (0,17–9,01) |

| CT | 15 (23,4) | 9 (22,5) | 0,91 | 1,05 (0,41–2,7) | 13 (25) | 10 (16,1) | 0,23 | 1,73 (0,68–4,36) | 2 (16,7) | 3 (20) | 0,82 | 0,8 (0,11–5,77) |

| CC | 2 (3,1) | 0 | 0,25 | ND | 1 (1,9) | 0 | 0,27 | ND | 0 | 0 | ND | ND |

| Alleles | ||||||||||||

| T | 109 (85,2) | 71 (88,7) | 0,46 | 0,72 (0,31–1,69) | 89 (85,6) | 114 (92) | 0,12 | 0,52 (0,22–1,21) | 22 (91,7) | 27 (90) | 0,83 | 1,22 (0,18–7,97) |

| C | 19 (14,8) | 9 (11,3) | 15 (14,4) | 10 (8) | 2 (8,3) | 3 (10) | ||||||

*Significant p-values appear in bold

However, after stratification by sex and age, no evidence of genetic associations between rs2228505 and PTB disease was found.

✓ Haplotype analysis

We did a haplotype analysis for two SNPs: rs1050504 and rs3808607. rs3808607 is located in the promoter region of the CYP7A1 gene and has been associated with TB in the same population [8].

In healthy individuals, all nine possible diplotype combinations were found. However, only eight diplotypes were found in PTB patients. Interestingly, data analysis found that the CT /AA diplotype was significantly more frequent in PTB patients in comparison to healthy controls and appeared to be associated with an increased risk for the development of pulmonary TB (12% vs. 1%, OR 13.5, 95% CI 1.72–105.9; p = 0.0006) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Distribution of the rs3808607 and rs1050504 diplotype frequencies in pulmonary tuberculosis patients and healthy controls

| Diplotypes | PTB Patients (n = 68) (%) | Controls (n = 90) (%) | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC/AA | 19 (28) | 24 (27) | 0.43 | 1.05 (0.56–1.95) |

| CT/AA | 8 (12) | 1 (1) | 0.0006* | 13.5 (1.72–105.9) |

| TT/AA | 0 | 1 (1) | 0.25 | Undefined |

| CC/AC | 16 (24) | 28 (31) | 0.13 | 0.7 (0.37–1.31) |

| CT/AC | 13 (20) | 18 (20) | 0.5 | 1 (0.5–1.99) |

| TT/AC | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.5 | 1 (0.06–16.2) |

| CC/CC | 5 (7) | 11(12) | 0.12 | 0.55 (0.2–1.46) |

| CT/CC | 5 (7) | 5 (6) | 0.39 | 1.17 (0.38–3.64) |

| TT/CC | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.5 | 1 (0.06–16.2) |

*Significant p-values appear in bold

When we analysed the four possible haplotypes, no significant difference was observed between PTB patients and healthy controls (Table 8).

Table 8.

Distribution of the rs3808607 and rs1050504 haplotype frequencies and LD statistics in pulmonary tuberculosis patients and healthy controls

| Haplotype | Haplotype frequencies % | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTB | CTRL | |||

| A-C | 53 | 51 | 0.38 | 1.08 (0.62–1.89) |

| A-T | 9 | 4 | 0.08 | 2.37 (0.7–7.97) |

| C-C | 25 | 32 | 0.13 | 0.7 (0.38–1.31) |

| C-T | 13 | 13 | 0.5 | 1 (0.43–2.28) |

| LD statistics | PTB | CTRL | ||

| D’ | 0.34 | 0.58 | ||

| r2 | 0.05 | 0.08 | ||

Moreover, the analysis of linkage disequilibrium (LD) revealed that the polymorphisms rs3808607 and rs1050504 were in low LD. The correlation (r2) between these two SNPs in patients and controls was weak (0.05 vs 0.08). In addition, the D’ data also showed evidence of a low LD between these SNPs. In patients, rs3808607 and rs1050504 are coinherited roughly 34% of the time. Therefore, the two SNPs are in weak LD in patients (D’ = 0.34) more than the in control group, where these two polymorphisms are coinherited approximately 58% of the time (D’ = 0.58).

Discussion

In Morocco, despite efforts that have been deployed, including the setup of a national tuberculosis programme, there is still a long way to go in the fight against TB.

Tuberculosis is a multifactorial disease wherein several parameters in the form of host genetic factors could affect disease outcome. In this regard, numerous studies have reported the crucial role played by the host genetic factors in term of the development of TB disease [27–30].

In the present study, we report for the first time a strong association between the rs1050504 NSMAF polymorphism and PTB disease in the Moroccan population. Our data show that the CT genotype is a susceptibility marker for TB and that the mutant TT genotype for rs1050504 plays a protective role against TB. Scarce data has been reported concerning the involvement of this variant on the outcome of TB disease. However, if we take in consideration the particular localization of rs1050504 SNP in 3’UTR (untranslated region) of the NSMAF gene, we could generate a hypothesis to explore our finding. In fact, it has been reported in several works that SNPs located in untranslated regions of genes may interfere with mRNA stability and translation, including causing a change in recognition sites for microRNAs (miRNA), RNA-binding proteins, and the polyadenylation machinery [31, 32]. Therefore, 3’UTR variants may result in observed differences in gene expression [32].

In this context, a recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) has reported that the rs1050504-C wild-type allele is located in a putative miRNA binding site for miR-154-3p [33], reported to act as a tumour suppressor in several types of malignancies [34, 35]. In a mutant allele, this miRNA binding site becomes another binding site, the role of which has not yet been explored [33]. This finding is of particular interest, especially when we know that FAN, the protein encoded by NSMAF, is implicated in apoptotic signalling [20, 22, 36]. Apoptosis is considered a particular innate defence against Mtb, and it is associated with diminished pathogen viability in infected macrophages [37, 38]. As a result, virulent Mtb strains have developed a capacity to disrupt this mechanism by various means, such as through expression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma/leukaemia 2) family, which can block the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria [39].

Taken together, we can hypothesize that the presence of the CT genotype could create conditions leading to downregulation of FAN. Conversely, the rs1050504TT SNP could decrease the ability of miRNA to down-regulate FAN, theoretically leading to increased FAN production. In turn, increased FAN could enhance apoptotic signalling to protect against PTB and/or likely affect other roles FAN plays in anti-TB immune response, such as Actin reorganization in macrophages [40] and navigational capacity of leucocytes chemotactic response [41], or its documented role in TNF-α induced neutrophil migration in mouse peritonitis models [21].

However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the association between the rs1050504 SNP and PTB may be secondary to the presence of one or more different variants in close linkage disequilibrium with the NSMAF gene or other genes. In particular, this candidate gene is located within the chromosomal region 8q12-q13, characterized by a high LOD score of susceptibility to PTB in the Moroccan population [11]. In addition, more recently, other SNPs located in genes that are closely linked to the NSMAF gene, TOX (rs2726600 and rs1568952) and CYP7A1 (rs3808607), have been associated with PTB [8, 42].

After stratification analysis, our data show that the association is maintained only in males but not in females. Males with the rs1050504 CT genotype are more susceptible to PTB, in contrast to those with the TT, which seems to be protective against PTB. These data reinforce the sexual inequality with respect to predisposition to TB; worldwide epidemiological data report that the majority of TB patients are male [43, 44]. This sex discrimination could be due to the sex hormones [43–45]. A previous finding reported that testosterone is immunosuppressive and impairs macrophage activation [46], while oestrogens are pro-inflammatory mediators able to induce the production of TNF-α and stimulate secretion of INF-γ [47, 48].

Interestingly, in our study, the patients between ages 30 and 49 with the TT genotype appeared to be at decreased risk of developing PTB (OR 0.22; p = 0.002). Theoretically, the NSMAF gene interacts with other genes encoding for cytokines or their receptors that play an essential role in defence against TB. This polygenic aspect of susceptibility to TB might in part explain our finding. When taking into account that genetic variants affecting genes encoding for cytokines or their receptors could be influenced by age and sex, as reported with the AA genotype variant of +874 A/T, affecting the IFN-g gene was associated with active PTB in men (OR 2.42) aged 30–49 years [49].

Analysis of the LD measures revealed that two SNPs (rs3808607 and rs1050504) are in LD. Nevertheless, the values of D’ and r2 indicated that this LD is low. Moreover, our results showed that when the AA rs3806607 genotype and CT rs1050504 genotype are coinherited, the susceptibility to develop TB is strongly significant (OR 13.5; p = 0.0006). These data confirm our previous finding wherein the AA rs3808607 genotype of the CYP7A1 gene is more frequent in PTB patients compared to HC (OR 1.93; p = 0.02) [8]. However, the lack of association between rs2228505 and rs36067275 SNPs and PTB in our study, at both the allelic and genotypic levels, could be explained by the absence of the effect of these genetic variants occurring at their positions.

In our study, we report for the first time the allele frequencies of these three SNPs in the Moroccan population, which could be used for others studies in the context of their potential involvement in other diseases. Indeed, data analysis of the rs1050504 SNP revealed that the T mutant allele frequency observed in the Moroccan population (0.29) is close to that reported in Han Chinese (0.32) and Caucasian (0.34) populations and higher than the frequencies observed in Japanese (0.2) and Sub-Saharan African populations (Yoruba) (0.08).

When we analysed the data for the rs2228505-C mutant allele, the allele frequency was 0.09 in Moroccan population, which is similar to that observed in the Sub-Saharan African population (Yoruba) (0.1), but it is much lower than that observed in the Han Chinese and Japanese (0.22, 0.33, respectively) and higher than that in the Caucasian population (CEU) (0.01). Therefore, it will be very interesting to evaluate the impact of the polymorphism of this variant in Chinese and Caucasian TB populations.

Concerning the result of the rs36067275 C > T SNP, we found that the T mutant allele is absent in the Moroccan population as observed in Caucasian (CEU), Han Chinese (HCB) and Japanese (JPT) populations. However, in the Sub-Saharan African population (Yoruba), this allele is present at 0.02 frequency [50].

Conclusion

In summary, our results suggest that the rs1050504 NSMAF SNP may have an impact on the susceptibility or resistance to PTB in the Moroccan population. We are, however, fully aware that the limitation of the current study is its small size. Hence, further studies using larger samples in ethnically diverse populations are needed to better understand the involvement of NSMAF in protection against TB. In addition, functional studies are highly recommended in order to evaluate the involvement of the NSMAF gene or its product in TB development.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients and healthy controls for their participation. We are sincerely grateful to the clinicians and nurses of the different prefectures (Marrakech, Rabat, Temara, Fes, Oujda, Tanger and Casablanca) for their collaboration.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the Hassan II Academy of Science and Technology, Kingdom of Morocco (Grant number 1169). It was also supported by the H3ABioNet project: a sustainable African Bioinformatics Network for H3Africa (Grant number 5U41HG006941). The funders had no role in the design of the study or data analysis and they have not seen the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of the current study is available from the corresponding author at a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 3’UTR

Untranslated region

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma/leukaemia 2

- CI

Confidence interval

- HC

Healthy controls

- INF-γ

Interferon-gamma

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- NSD

Neutral sphingomyelinase domain

- NSMAF

Neutral sphingomyelinase activation associated factor

- OR

Odds ratio

- TB

Tuberculosis

- TNFRI

Tumour necrosis factor receptor type I

- TNF-α

Tumour necrosis factor-alpha

Authors’ contributions

MQ participated in sampling, SNP genotyping of NSMAF gene, and data analysis and drafted the manuscript; IA participated in sampling and SNP genotyping of the NSMAF gene; JEB was in charge of patient recruitment and clinical evaluation; RE participated in the design and coordination of the project; and KS participated in the conception and design of the study and review of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The participants signed an informed consent form. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee for Biomedical Research, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Mohammed V University of Rabat.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mounia Qrafli, Email: mounia.qrafli@gmail.com.

Imane Asekkaj, Email: imane.asekkaj@gmail.com.

Jamal Eddine Bourkadi, Email: jebourkadi@yahoo.com.

Rajae El Aouad, Email: rajaealouad@yahoo.fr.

Khalid Sadki, Phone: +212 (0) 5 37 77 18 34/35/38, Email: ksadki1@yahoo.fr, Email: khalidsadki1@gmail.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed on 4 Oct 2016.

- 2.Direction de l'Epidémiologie et de Lutte Contre les Maladies. Situation épidémiologique de la TB au Maroc-en 2015. 2015. Available from : http://www.sante.gov.ma/Documents/2016/03/Situation_%C3%A9pidimio_de_la_TB_au_Maroc__2015%20Fr%20V%2020%20%20mars.pdf. Accessed on 9 Nov 2016.

- 3.Daly AK, Day CP. Candidate gene case-control association studies: advantages and potential pitfalls. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52:489–499. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01510.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khoury MJ, Yang Q. The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases: an epidemiologic perspective. Epidemiol Camb Mass. 1998;9:350–354. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199805000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Risch N, Merikangas K. The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science. 1996;273:1516–1517. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arji N, Busson M, Iraqi G, Bourkadi JE, Benjouad A, Bouayad A, et al. Genetic diversity of TLR2, TLR4, and VDR loci and pulmonary tuberculosis in Moroccan patients. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:430–440. doi: 10.3855/jidc.3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamsyah H, Rueda B, Baassi L, Elaouad R, Bottini N, Sadki K, et al. Association of PTPN22 gene functional variants with development of pulmonary tuberculosis in Moroccan population. Tissue Antigens. 2009;74:228–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qrafli M, Amar Y, Bourkadi J, Ben Amor J, Iraki G, Bakri Y, et al. The CYP7A1 gene rs3808607 variant is associated with susceptibility of tuberculosis in Moroccan population. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:1. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.1.3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabri A, Grant AV, Cosker K, El Azbaoui S, Abid A, Abderrahmani Rhorfi I, et al. Association study of genes controlling IL-12-dependent IFN-γ immunity: STAT4 alleles increase risk of pulmonary tuberculosis in Morocco. J Infect Dis 2014;210:611–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Sadki K, Lamsyah H, Rueda B, Akil E, Sadak A, Martin J, et al. Analysis of MIF, FCGR2A and FCGR3A gene polymorphisms with susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis in Moroccan population. J Genet Genomics Yi Chuan Xue Bao. 2010;37:257–264. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(09)60044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baghdadi JE, Orlova M, Alter A, Ranque B, Chentoufi M, Lazrak F, et al. An autosomal dominant major gene confers predisposition to pulmonary tuberculosis in adults. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1679–1684. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Kreder D, Schwandner R, Krut O, Scherer G, Adam-Klages S, et al. Assignment of the human FAN protein gene (NSMAF) to human chromosome region 8q12-->q13 by in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1999;87:115–116. doi: 10.1159/000015375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The National Center for Biotechnology Information. 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/. Accessed on 24 May 2017.

- 14.Kreder D, Krut O, Adam-Klages S, Wiegmann K, Scherer G, Plitz T, et al. Impaired neutral sphingomyelinase activation and cutaneous barrier repair in FAN-deficient mice. EMBO J. 1999;18:2472–2479. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adam-Klages S, Schwandner R, Adam D, Kreder D, Bernardo K, Krönke M. Distinct adapter proteins mediate acid versus neutral sphingomyelinase activation through the p55 receptor for tumor necrosis factor. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63(6):678–682. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.6.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adam-Klages S, Adam D, Wiegmann K, Struve S, Kolanus W, Schneider-Mergener J, et al. FAN, a novel WD-repeat protein, couples the p55 TNF-receptor to neutral sphingomyelinase. Cell. 1996;86:937–947. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krut O, Wiegmann K, Kashkar H, Yazdanpanah B, Krönke M. Novel tumor necrosis factor-responsive mammalian neutral sphingomyelinase-3 is a C-tail-anchored protein. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13784–13793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Philipp S, Puchert M, Adam-Klages S, Tchikov V, Winoto-Morbach S, Mathieu S, et al. The Polycomb group protein EED couples TNF receptor 1 to neutral sphingomyelinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1112–1117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908486107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ségui B, Andrieu-Abadie N, Jaffrézou J-P, Benoist H, Levade T. Sphingolipids as modulators of cancer cell death: potential therapeutic targets. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758(12):2104–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ségui B, Andrieu-Abadie N, Adam-Klages S, Meilhac O, Kreder D, Garcia V, et al. CD40 signals apoptosis through FAN-regulated activation of the sphingomyelin-ceramide pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37251–37258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montfort A, de Badts B, Douin-Echinard V, Martin PGP, Iacovoni J, Nevoit C, et al. FAN stimulates TNF(alpha)-induced gene expression, leukocyte recruitment, and humoral response. J Immunol. 2009;183(8):5369–5378. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien NW, Gellings NM, Guo M, Barlow SB, Glembotski CC, Sabbadini RA. Factor associated with neutral sphingomyelinase activation and its role in cardiac cell death. Circ Res. 2003;92:589–591. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000066290.29715.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arthur AT, Armati PJ, Bye C, Heard RN, Stewart GJ, Pollard JD, et al. Genes implicated in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis from consilience of genotyping and expression profiles in relapse and remission. BMC Med Genet. 2008;9:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goris A, Sawcer S, Vandenbroeck K, Carton H, Billiau A, Setakis E, et al. New candidate loci for multiple sclerosis susceptibility revealed by a whole genome association screen in a Belgian population. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;143:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boecke A, Carstens AC, Neacsu CD, Baschuk N, Haubert D, Kashkar H, et al. TNF-receptor-1 adaptor protein FAN mediates TNF-induced B16 melanoma motility and invasion. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:422–432. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaunt TR, Rodríguez S, Day IN. Cubic exact solutions for the estimation of pairwise haplotype frequencies: implications for linkage disequilibrium analyses and a web tool “CubeX.”. BMC Bioinf. 2007;8:428. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellamy R, Beyers N, McAdam KP, Ruwende C, Gie R, Samaai P, et al. Genetic susceptibility to tuberculosis in Africans: a genome-wide scan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8005–8009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140201897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casanova J-L, Abel L. Genetic dissection of immunity to mycobacteria: the human model. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:581–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.081501.125851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comstock GW. Tuberculosis in twins: a re-analysis of the Prophit survey. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;117(4):621–624. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.117.4.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kallmann FJ, Reisner D. Twin studies on genetic variations in resistance to tuberculosis. J Hered. 1943;34:269–276. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a105302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan BM, Robles AI, Harris CC. Genetic variation in microRNA networks: the implications for cancer research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:389–402. doi: 10.1038/nrc2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skeeles LE, Fleming JL, Mahler KL, Toland AE. The impact of 3’UTR variants on differential expression of candidate cancer susceptibility genes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghanbari M, Franco OH, de Looper HWJ, Hofman A, Erkeland SJ, Dehghan A. Genetic variations in MicroRNA-binding sites affect MicroRNA-mediated regulation of several genes associated with cardio-metabolic phenotypes. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2015;8:473–486. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Kai Y, Qiang C, Xinxin P, Miaomiao Z, Kuailu L. Decreased miR-154 expression and its clinical significance in human colorectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:195. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0607-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 35.Lin X, Yang Z, Zhang P, Shao G. miR-154 suppresses non-small cell lung cancer growth in vitro and in vivo. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:3053–3060. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ségui B, Cuvillier O, Adam-Klages S, Garcia V, Malagarie-Cazenave S, Lévêque S, et al. Involvement of FAN in TNF-induced apoptosis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(1):143–151. doi: 10.1172/JCI11498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Behar SM, Martin CJ, Booty MG, Nishimura T, Zhao X, Gan H-X, et al. Apoptosis is an innate defense function of macrophages against mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:279–287. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen M, Gan H, Remold HG. A mechanism of virulence: virulent mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv, but not attenuated H37Ra, causes significant mitochondrial inner membrane disruption in macrophages leading to necrosis. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. 2006;176:3707–3716. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Q, Gong B, Mahmoud-Ahmed AS, Zhou A, Hsi ED, Hussein M, et al. Apo2L/TRAIL and Bcl-2–related proteins regulate type I interferon–induced apoptosis in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2001;98(7):2183–2192. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.7.2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peppelenbosch M, Boone E, Jones GE, van Deventer SJ, Haegeman G, Fiers W, et al. Multiple signal transduction pathways regulate TNF-induced actin reorganization in macrophages: inhibition of Cdc42-mediated filopodium formation by TNF. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. 1999;162:837–845. [PubMed]

- 41.Boecke A, Sieger D, Neacsu CD, Kashkar H, Krönke M. Factor associated with neutral Sphingomyelinase activity mediates navigational capacity of leukocytes responding to wounds and infection: live imaging studies in Zebrafish larvae. J Immunol. 2012;189(4):1559–1566. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grant AV, El Baghdadi J, Sabri A, El Azbaoui S, Alaoui-Tahiri K, Abderrahmani Rhorfi I, et al. Age-dependent association between pulmonary tuberculosis and common TOX variants in the 8q12-13 linkage region. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92:407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neyrolles O, Quintana-Murci L. Sexual inequality in tuberculosis. PLoS Med. 2009;6 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Nhamoyebonde S, Leslie A. Biological differences between the sexes and susceptibility to tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(Suppl 3):S100–S106. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bini EI, Mata Espinosa D, Marquina Castillo B, Barrios Payán J, Colucci D, Cruz AF, et al. The influence of sex steroid hormones in the immunopathology of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.D’Agostino P, Milano S, Barbera C, Di Bella G, La Rosa M, Ferlazzo V, et al. Sex hormones modulate inflammatory mediators produced by macrophages. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;876:426–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zuckerman SH, Bryan-Poole N, Evans GF, Short L, Glasebrook AL. In vivo modulation of murine serum tumour necrosis factor and interleukin-6 levels during endotoxemia by oestrogen agonists and antagonists. Immunology. 1995;86(1):18–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fox HS, Bond BL, Parslow TG. Estrogen regulates the IFN-gamma promoter. J Immunol. 1991;146(12):4362–4367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selma WB, Harizi H, Bougmiza I, Hannachi N, Kahla IB, Zaieni R, et al. Interferon gamma +874T/a polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to active pulmonary tuberculosis development in Tunisian patients. DNA Cell Biol. 2011;30:379–387. doi: 10.1089/dna.2010.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.genomes browser. 2017. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/variation/tools/1000genomes/. Accessed on 24 May 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset of the current study is available from the corresponding author at a reasonable request.