Abstract

Introduction:

This paper looks at the market food environments of First Nations communities located in the provincial Norths by examining the potential retail competition faced by the North West Company (NWC) and by reporting on the grocery shopping experiences of people living in northern Canada.

Methods:

We employed two methodological approaches to assess northern retail food environments. First, we mapped food retailers in the North to examine the breadth of retail competition in the provincial Norths, focussing specifically on those communities without year-round road access. Second, we surveyed people living in communities in northern Canada about their retail and shopping experiences.

Results:

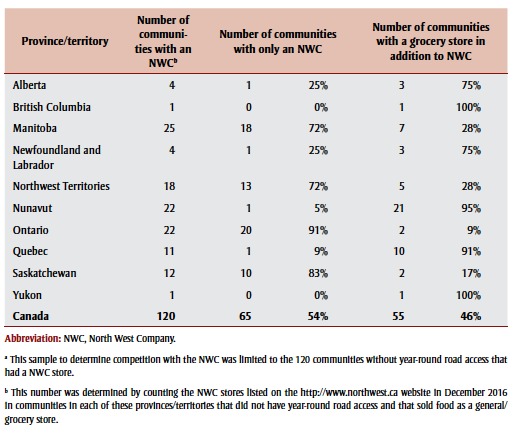

Fifty-four percent of communities in the provincial Norths and Far North without year-round road access did not have a grocery store that competed with the NWC. The provinces with the highest percentage of northern communities without retail competition were Ontario (87%), Saskatchewan (83%) and Manitoba (72%). Respondents to the survey (n = 92) expressed concern about their shopping experiences in three main areas: the cost of food, food quality and freshness, and availability of specific foods.

Conclusion:

There is limited retail competition in the provincial Norths. In Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Ontario, the NWC has no store competition in at least 70% of northern communities. Consumers living in northern Canada find it difficult to afford nutritious foods and would like access to a wider selection of perishable foods in good condition.

Keywords: food environments, retail, food quality, provincial Norths, northern Canada

Highlights

Communities without access to allseason roads face extremely high rates of food insecurity.

Northern retail environments are unique and differ from southern and urban locales.

The North West Company operates within an oligopoly in the provincial Norths.

Limited retail competition may be a contributing factor to food insecurity in northern Canada.

The greatest concern northern participants expressed about food purchasing fell within three main areas: the high cost of food, the quality of food available (e.g. whether fresh or expired), and the availability, selection and variety of specific foods (e.g. fresh produce and dairy products).

Introduction

Northern retail environments are unique and differ from southern and urban locales, thereby posing meaningful challenges to food security.1 Significantly, conflating the provincial Norths and Far North (the Northwest Territories, the Yukon, and Nunavut) fails to capture the unique contexts and challenges that characterize food retailing in these locales. An in-depth examination of the retail environment in the provincial North reveals several things: that the lack of retail competition and choice, as well as extremely long supply chains and their attendant costs, result in exceptionally high food costs and serious concerns about food quality, availability and selection/variety.2-5 The termination of the federal Food Mail Program (a transportation subsidy applied to select foods and goods) and its replacement by Nutrition North Canada (NNC) (a subsidy for select foods paid directly to retailers) in 2011 brought the high cost of food to light.6

Grassroots Indigenous movements and organizations responding to the changes in the subsidy program have brought the extremely high rates of food insecurity in the Canadian North to the attention of the broader Canadian public through social media campaigns and on Facebook pages such as Feeding My Family.7 Such community responses have been echoed by academics and international organizations. In 2014, for example, the Council of Canadian Academies published Aboriginal Food Security in Northern Canada: An Assessment of the State of Knowledge, which reported that food insecurity in northern Canada is a pressing and immediate issue demanding urgent attention.8 This analysis was preceded in 2012 by the report of Olivier De Schutter, then the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on the right to food, on his visit to Canada, which revealed that 60% of on-reserve Indigenous households in northern Manitoba were food insecure, as were 70% of Inuit adults in Nunavut.9 De Schutter further noted that these rates of food insecurity were six times higher than the national average and “represent[ed] the highest documented food insecurity rate for any aboriginal population in a developed country.”9 While the situation in the Far North is extremely important, discussions of food insecurity have remained focussed on that region (specifically, Nunavut). And while Nunavut (and the NWT and Yukon) needs access to NNC (and to better, more effective programs designed to lower the cost of food and increase access to land- and waterbased foods), the focus of this research is on the retail food environments of First Nations communities in the provincial Norths.

The all-encompassing use of the term northern has created confusion as to what constitutes the “North.” We are concerned about the conflation of the provincial Norths and Far North and the reduction of the experiences of what are two different regions undergoing food crises to one representative experience. Canada’s “North” represents 96% of the country’s landmass and includes widely disparate geographic and culturally diverse peoples situated within different economic, political and social environments. Notably, the one continuity between these regions is the disproportionate rates of food insecurity among Indigenous peoples living in rural and northern communities, and the presence of corporate oligopolies.

In this article, we focus on the provincial Norths, often referred to as “Canada’s forgotten North.”10,p.312 Frequently, the provincial Norths are absent from conversations about the “North,” which generally refers to the Far North (Nunavut, Northwest Territories and the Yukon).11 While the provincial Norths tend to have more in common with the Far North than the urban south, conflating the regions does them a disservice and fails to adequately account for their distinctive features. Such totalized discourse concerning northern Indigenous populations also does the colonial work of homogenizing First Nations and Inuit peoples and removing them from the specific contexts, geographies and histories in which they are situated.

Background

Over the past decade, a growing body of scholarship that examines food insecurity and environments in First Nations and Inuit communities has developed. However, the majority of this literature remains focussed on the Far North and the landand water-based practices of the Inuit. Discrete studies exist on the provincial Norths, focussing on specific communities but concentrating primarily on measuring rates of food insecurity. For instance, a 2012 study of 14 communities in northern Manitoba found that three out of every four households (75%) were food insecure. The incidence and severity of food insecurity varied, with fly-in communities generally having more severe and higher rates of food insecurity than those with road or train access.12 Similarly, a 2013 study in Fort Albany First Nation, located along the James Bay coast in present-day northern Ontario, found that 70% of households suffered from food insecurity. 13 Both works note that the retail environments of fly-in First Nations have limited options, and that lack of access to all-weather roads has an enormous impact on food security.12 The largest and most common retailer in First Nations communities in the provincial Norths is the North West Company (NWC). Also known as the Northern Store, the NWC has a long history in these communities as the former Northern Department of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). In 1987, executives of the HBC and private investors purchased the Northern Department and opened the NWC with an increased focus on retail food sales.14,15

Within a market environment of restricted retail options, retailers have an enormous opportunity to shape local food environments and peoples’ access to foods. Academics such as Teresa Socha and her colleagues noted that community members regarded the profit-driven model adopted by retailers as a significant barrier to affordable food.3,4 These researchers posed an important question in relation to the high cost of food: that is, “food or profitability?”3,p.58 Their 2011 study compared the prices of food between grocery retailers in Thunder Bay and a remote First Nation located in northwestern Ontario, arguing that resolving food insecurity in the provincial North was premised on “solving problems related to the food chain, including transportation, food accessibility, and food availability.”3,p.58

Solutions to food insecurity include increasing Indigenous peoples’ access to land- and water-based foods through supporting community food sharing networks, harvester and hunter support programs and community freezers.4,12,16 In other words, Indigenous food sovereignty is essential to decolonizing local food environments. However, Indigenous food sovereignty has focussed primarily on control over land- and water-based foods, and while this is extremely important, such a focus can obscure the fact that market-based food systems remain prohibitive in terms of costs and negligent regarding food selection and quality. While food sovereignty is imperative in First Nations communities, it does not preclude the need to have equitable market- based foods systems in operation and under local control as well. Indeed, the need to address the existing market-based food system and the oligopolies that have facilitated the current conditions present in most northern communities is urgent. A comprehensive solution is required that includes both land-and-water-based and market-based food systems and that places a critical focus on the profit-producing operations of retailers in the region.

Historical context

Hunger and food insecurity in First Nations communities located in the provincial Norths are not recent phenomena; they have their roots in settler colonialism and the erosion of Indigenous peoples’ access to their foodways.2,8,9 The establishment of reserves failed to draw on the knowledge and preferences of Indigenous peoples who had lived on and managed their territories and resources since time immemorial. Nor were reserves established with consideration for proximity to food, clean water, medicines or suitability for long-term settlement. In direct violation of the treaties, provincial hunting laws criminalized Indigenous hunting practices by making it illegal to hunt certain animals, thereby preventing Indigenous peoples from hunting during specific seasons, and created bag limits (restrictions on the number of animals within a particular species that hunters may kill and keep).17-20 For example, in the First Nations Food, Nutrition, and Environment Study, 65% of participants in on-reserve communities in British Columbia reported that government restrictions affected or limited where they could hunt, fish or collect berries. Indeed, government restrictions were identified as the biggest barrier to harvesting activities.21

Under Canada’s residential school system, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and communities and confined to schools that were designed to assimilate them. These schools had, and continue to have, a profound impact on the intergenerational transmission of the knowledge required to harvest and prepare wild foods.22 Climate change has also altered animal migration patterns and reduced the ability of people to continue to hunt and fish.8 Nevertheless, the harvesting, preparation and consumption of traditional foods remains deeply embedded in the familial, cultural and social fabric of communities and is an essential component of both the social and physical wellbeing of First Nations.8,22

After the Second World War, the federal government undertook a series of social welfare and food subsidy programs as well as education initiatives that had the effect of undermining Indigenous foodways and resulted in Indigenous people becoming increasingly reliant on southern market-based food systems. For instance, in the late 1960s, the federal government instituted a transportation subsidy for a select list of foods to be run through Canada Post, called the Food Mail Program. This subsidy existed until April 2011, when it was replaced by Nutrition North Canada. NNC is a retail-based program intended to subsidize the high cost of perishable, nutritious foods in the North. Retailers receive a subsidy on certain foods that are flown into eligible northern communities. The subsidy is applied on two levels (high or low) for perishable and nutritious foods, and is based on destination and weight. Registered retailers receive the subsidy directly and are responsible for passing along the full savings to their customers with little to no oversight. Until 01 October, 2016, in northern Ontario there were 32 fly-in communities and only eight fully eligible communities,23 although all were desperately in need of the food subsidy.6

The program came under serious criticism in the Auditor General’s report in 201424, which found that community eligibility was not based on need and Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada had not verified whether the NNC subsidy was passed onto consumers in full. Following the election of the Liberal government in fall of 2015, another 37 communities were made eligible for the NNC subsidy after October 1, 2016; 19 of these new communities are located in northern Ontario.23 Consultations have recently been conducted with NNC stakeholders to determine how the program might be improved.25 What the Auditor General’s report24 did not address was the lack of retail competition in many First Nations communities located in the provincial Norths. Many Indigenous on-reserve communities in the provincial Norths are accessible only by plane or sea barge, and briefly by seasonal ice roads. As a result of long transportation routes, the cost of food is prohibitively high, food selection and quality is limited and communities are usually serviced by a single grocery store. One of the major factors contributing to food insecurity in northern First Nations populations is the relative cost of accessing food, whether from increasing dependence on the market (imported) food system or the rising costs of participating in land- and water-based food-harvesting activities.26

Objectives

The objective of this research was to examine the retail food environment in northern Canada in two ways: (1) by considering whether the NWC has market competition for grocery retailing in communities without year-round road access; and (2) by inviting people living in semiremote and remote communities to share their experiences of the retail food environment in the North. It is very challenging to recruit people living in semi-remote and remote communities to participate in surveys and obtain their perspectives on northern issues. While we acknowledge that there are some methodological limitations to the approaches we were able to use, including a small sample size, this paper presents an important contribution to a very scant body of literature on the topic of retail environments in northern Canada.

Methods

We employed two approaches to assess northern retail food environments. The first was designed to determine whether the NWC faces substantive competition in the North, since the NWC is the major grocery retailer across northern Canada. To accomplish this, we initially created a list of all the northern communities in Canada without year-round road access. We then checked these communities to determine whether they had a NWC store, based on the list of stores on the NWC website (http://www.northwest.ca) in December 2016. From this list, we ascertained whether that store faced any retail competition by searching and listing other stores in the same community that had a full-service grocery store. Thus, small, locally owned convenience stores were not counted as competitors to NWC stores.

We included a community in our study if it met any of the following criteria: it was located in the provincial Norths, Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Nunavik, or Labrador; it was part of the NNC program; it was included in the article “From Food Mail to Nutrition North Canada: Reconsidering Federal Food Subsidy Programs for Northern Ontario,” published in Canadian Food Studies in May of 2015;6 or, finally, it was listed on the NWC website. In northern Ontario, we also included the municipality of Moosonee because it serves as an important entry point for northern First Nations in the Mushkegowuk territories for services (food, general goods and health care) and is only accessible year-round by rail (as all-season roads are not yet operational). Any store that sold food as a general store or grocery store was included in the study. We counted those stores that had more than one operation in the community (i.e. the NWC often operates a grocery store in addition to a gas station or “Quick-Stop”), which are often contained in more than one building, as one store despite the multiple locations and different retail focusses. While further breaking down these smaller categories may offer additional insight into the breadth and scope of the oligopolies operating in northern communities, such an inquiry is not within the scope of this article.

The second approach was to collect data from community members living in northern Canada using an online survey tool that was developed in consultation with community members and Elders. The Ontario-based Northern Food Sovereignty Advisory Group (FSAG) comprises seven food activists and community members, including one Elder, who live in communities in northern Ontario and have formed an advocacy group engaging with issues of food sovereignty and addressing current relationships of power and inequality through various activities. We worked with the FSAG over the course of two years, and during our discussions it became clear that there were serious concerns around best-before and expiry dates, food quality, food preference and retail practices, as well as a desire for more information about these issues. We drafted a survey to try and address these concerns, using a scale from one to five and comment boxes to encourage participants to further elaborate on those issues about which they felt most strongly. The failure of people to understand best-before dates is a frequent critique offered by retailers, and so, after a lengthy discussion with community members, we chose to use the term “expired foods.” “Expired” is the term most commonly used by community members and the perception that “best before” and “expired” are synonymous is relevant when considering what informs people’s purchasing decisions (packaged foods that are being sold after the best-before date). The survey went through a revision process of four drafts in consultation with five of the FSAG community members and the Elder.

The survey was launched using the online survey tool FluidSurveys (Fluidware, Ottawa, ON, CAN) on November 12, 2014, and closed December 31, 2014. We invited northern residents in Canada to share their experiences and concerns about food purchasing experiences with local retailers. To promote the survey and encourage northern residents to participate, postcards explaining the study were distributed at the 2014 Food Secure Canada conference and to our community partners to share with their own social networks. Northern media and social media outlets (e.g. the Feeding My Family Facebook group) were widely contacted as well as northern organizations engaged with food security issues and health and well-being concerns more generally. Due to the significant constraints of conducting survey research in remote communities, we were limited to a convenience sample of participants. Incentives were not provided to survey participants.

Results

Store competition

Across Canada, there are 120 NWC stores (or various iterations of the store: North Mart, Northern) located in either the provincial Norths or Far North that do not have year-round road access, and are briefly accessible in the winter by seasonal ice roads or rail. The NWC operates the sole grocery store in 65 of the 120 communities (or 54%). An additional 55 communities have a second full-service grocery store. In other words, the NWC is the only full-service grocery store in 54% of the communities in which it operates in Canada.

This picture is further complicated if we break down the number of NWC stores according to province and territory. Table 1 shows the number of NWC stores that face competition from at least one non- NWC full-service grocery store in each province or territory. Those provinces that have the highest number of NWC stores are Manitoba, Ontario and Saskatchewan, where the company faces almost no competition. Proportionately, NWC stores located in northern First Nations in Ontario face the least competition; 91% of their stores face absolutely no retail competition. Eighty-three percent and 72% of the communities in northern Saskatchewan and Manitoba, respectively, are serviced only by an NWC store.

TABLE 1. North West Company competitiona by province or territory, Canada, 2016.

|

Retail experiences

The second element of this work was to assess the retail environment through individual experiences and perceptions of the high cost of food; the quality of the food available to purchase (e.g. whether fresh or expired); and availability and selection or variety of specific foods (e.g. fresh produce and dairy products). Of the 113 people who started the survey, we excluded those who only completed the first few questions of the survey (n = 20) and one person who was living in the United States. The following descriptive analyses were conducted using data from the remaining respondents (n = 92).

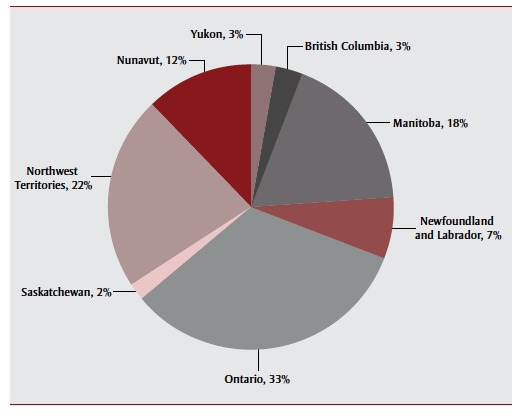

The majority of people who responded to the survey were women (71.7%); 27.2% of all respondents were aged 35 to 44 years; 25.0% were aged 25 to 34 years, and 21.7% were aged 45 to 54 years. Twentyone percent of respondents had 5 or more people living in their household, with an average of 3.4 people per home. Approximately one-third of our respondents (32.6%) resided in northern Ontario; the next highest number of respondents were from Northwest Territories (21.7%), Manitoba (18.5%) and Nunavut (12.0%). Eight of the provinces and territories were represented (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Geographic representation and percentage of survey respondents from each province and territory.

Eighty-nine percent of respondents identified themselves as currently residing in a remote or semi-remote community. All of the people who did not currently live in a remote or semi-remote community but had lived in one previously were asked to provide their perspective from when they had lived there.

About half (51.1%) of respondents lived in a community with year-round road access. Of the respondents who mentioned the cost of gasoline (n = 74, 80.4%), the average cost was $1.59 per litre and ranged from $1.00 to $3.00 per litre.

The majority of respondents reported doing most of the food shopping for their household (84.7%). The store that respondents indicated they used most often as their primary retailer was the NWC (49.5%), followed by private, locally owned stores (18.9%), a community-owned store (15.8%) and Arctic Co-operatives (6.3%). When asked, “Does the store sell expired food?” with the response options of “Often,” “Sometimes,” “Never” or “I don’t know,” 82% of respondents stated that their store often or sometimes sold expired food. When asked, “Is the perishable food usually in good condition?” with the response options of “Yes” or “No,” more than half (57%) of the respondents said perishable food was not usually in good condition. Those respondents who said that perishable food was not usually in good condition were able to provide comments about the condition of this food in their store. Their comments described foods that were not fresh; shopping practices that involved paying great attention to checking food quality prior to purchasing perishables; and difficulties related to food freshness and quality that arose from long transportation routes. (“More often than not, they are close to rotten or rotten when they arrive,” wrote a participant from a remote community in northern Manitoba). Some described the food as having variable quality (e.g. a participant from a remote community in Yukon commented “Highly variable—sometimes arrive in good condition, bananas and cucumbers regularly frozen/soggy”). Some reported having to make sure to consume it quickly after purchase (e.g. a participant from a remote community in the Northwest Territories defined her fresh food purchases as “rotten, or so ripe [they] must be consumed immediately,” and another participant from a semi-remote community in northern Ontario wrote, “Usually have to use the day you buy it.”) Several people described the winter months as a time when perishable food was of poorer quality, while others explained it was an issue all year round (“They don’t last longer than a day or two once purchased…. Winter months are worse than summer months,” offered one participant from a remote community in Nunavut).

When asked, “What is your biggest concern when shopping at your primary retailer?”, the greatest concerns participants expressed regarding food purchasing fell within three main areas: the high cost of food; the quality of the food available to purchase (e.g. whether fresh or expired); and the availability and selection or variety of specific foods (e.g. fresh produce and dairy products). When asked, “What are the top five food items you purchase most often?” the food purchased most often was milk. When participants were asked, “Name the top three fresh or perishable healthy foods that you think should be made more affordable,” they chose produce (i.e. fresh fruit and vegetables), followed closely by milk and meat.

At the end of the survey, participants were asked if they had any additional concerns or if there were questions that they had not been asked. Twenty-seven people (29.3%) provided additional comments. Some of the comments included possible reasons for the lack of variety and quality of products available to them, such as this from a member of a remote community in Nunavut:

The lack of variety comes from the Head Office as the employees are only limited to what they can order in the order guide. Also they have get in a lot of their own brand which is horrible because they make more money on selling their own brand. Also we have notice even the groceries coming in on the barge which should be cheaper because it is barged in, is at the same price as the groceries coming in on the planes. Also all this non food items all seem to be cheap stuff but they sell it at huge prices ... crap we can buy in dollar stores down south but they mark it up so much. Now we know why The North West Company always makes a profit because the prices are out of this world.

Others were very focussed on the high cost of specific staple foods compared to those that were less healthy, such as this from a remote community in northern Manitoba:

Why isn’t the price of milk, eggs, bread, etc the staples of a household not regulated across the country? I have never seen any of the above go on sale. Cost of 4 litres of milk is over $8.50, in the northern town where I live. Yet 2 litres of Pepsi & coke products can go on sale for $1.00, potato chips go on sale. Alcohol is regulated, but milk is not, something has to be done about that.

Comments also provided details about some of the challenges to food access during specific times of the year and how that impacted prices: “During spring break-up and fall freeze up we chopper groceries across. I see food prices go up during this time, but they never go back down” (from a member of a remote community in Northwest Territories). Several respondents also described the cost of food in comparison to the cost of living: “How are you supposed to make a living when milk is 15 dollars? I know that’s not even the worst in Canada, but seriously. People have to feed their families and all they can afford is the terrible and unhealthy pre packaged food” (from a remote community in northern Ontario). Finally, a number of respondents questioned the profits made by retailers and referenced government subsidy programs, including the NNC subsidy: “I believe that there needs to be more transparency with how much the food costs, how much the retailer profits, and how much the government is subsidizing the rates by” (from a remote community in the Northwest Territories).

Discussion

In this paper, we highlight the scope of the NWC’s food retailing operations in the provincial North, and describe the context of the food retail environment in the Far North and provincial Norths by drawing on the perspectives of people living in those communities. Reducing the experiences and contexts of many different communities and locales within a vast area to one described as simply the “North” does not adequately address the nature of the retail and food environments of northern Indigenous communities. There are significant differences between the Far North and the provincial Norths, as well as within those regions and communities. Our objective was to address and illustrate some of the unique challenges that many First Nations communities in the provincial Norths face in acquiring market-based foods, both in terms of the lack of competition, the existence of oligopolies, and general retail experiences.

Our analysis of retail competition in northern Canada demonstrated that the NWC holds market dominance in the provincial Norths especially when it comes to the sale of food. Between 1987 (when the Northern Department of the Hudson’s Bay Company was sold to executives of the Northern Store and private investors) and 2015, the portion of those profits from the sale of food has more than doubled from just over 30% to 79.3%.27 Indeed, participation in a retail food market has proven so profitable to the NWC that the company expanded in 2007 through the Cost- U-Less initiative to the South Pacific and Caribbean, citing “a leading competitive position that’s supported by high barriers to entry.”27 The market dominance of the NWC in the North is facilitated by the company’s ability to access government subsidy programs such as Nutrition North Canada and its predecessor, the Food Mail Program. During the 2014/15 fiscal year, the NWC received the majority (50%) of the NNC subsidy from the federal government, while the recipient of the next highest amount was the Arctic Co-operatives, located primarily in Nunavut, Northwest Terroties and Yukon, at only 19%.28

The regions that contained the highest number of NWC stores in Canada were northern Manitoba and Ontario (with 25 and 22 stores respectively). Very few of our sample communities contained a second full-service grocery store: in northern Ontario there is one First Nation that has a second full-service grocer, and in Manitoba there are seven. While the challenging retail environment has limited retail competition and precluded the establishment of more than one grocery store in many communities, those retailers that do operate in northern First Nations continue to make a significant profit. A 2014 report on NNC, entitled “Northern Food Retail Data Collection and Analysis,” commissioned and released by the federal government said that while “retailers were unwilling to provide specific financial information regarding the profitability of their northern retailing operations,” it nonetheless concluded that “northern grocery retailers are making a profit from their activities in northern communities and therefore profit is a factor contributing to the overall cost of groceries.”29

The online survey we conducted in northern Canada provides texture to the description of the retail environments and brings into sharper focus a number of the issues highlighted in the November 2014 Auditor General’s report on NNC,24 the recently released Government of Canada report about the NNC public community engagement process,25,30 and an external program evaluation.31 The government report summarized general observations from community members about the public engagement process as follows:

Northerners feel that everything in the North is expensive, with a number of participants stating that, as Southerners, it is difficult to understand those struggles, which is then further intensified with many people living off a fixed income. Even with the subsidy provided through NNC, for which they generally expressed an appreciation, many families are not able to afford healthy food. There were significant concerns regarding the overall quality and availability of nutritious perishable food in the North.30

Our findings from surveying the experiences of northerners with retail food access generally aligned with these observations. People living in northern and rural First Nations that are accessible briefly by seasonal ice roads demand access to a wider selection of food that is in good condition at affordable prices. The quality of perishable foods poses a significant concern and often serves as a barrier to the purchase of fresh foods. The fear of spending money on inedible food may prevent people from taking the risk of buying new types of food, or make them decide to purchase ready-made or fast foods that they can be fairly sure they will be able to eat. Indeed, quality consistently remains one of the principal concerns expressed by community members but continues to be considered the least important factor when it comes to research design or assessing the success of the NNC program, both of which to date have focussed on collecting the prices of a select list of foods from the Revised Northern Food Basket (RNFB).* A failure to understand the dynamic between food quality and food purchasing practices in the North adds to the misconception that people in First Nations communities in the provincial Norths choose to purchase unhealthy, prepackaged and processed foods rather than healthier fresh produce and perishable items; in fact, food purchasing decisions are often influenced by past experiences of purchasing rotten, mouldy or less-than-fresh food that is inedible.

Finally, while all community members have questioned the current terrain of the retail environment that exists in fly-in and northern First Nations located in the provincial Norths, there is a real and marked failure on the part of government agencies to pose those same questions. The 2014 Auditor General’s report on NNC noted that some communities in northern Ontario were eligible for NNC and others were not. It made no mention, however, of the dominance of the market-based food system by one company and that company’s influence on and access to the decisionmaking processes that affected Indigenous communities. For instance, when consultations on the Food Mail Program were undertaken in 2007 to 2008, the NWC’s consultation with Dargo and Associates (the consulting firm) was either on par with that of communities and First Nations or even, in some cases, exceeded the access given to community members.33 What is more, this report argued that the relationship between the federal government and food retailers “encourages market disruption and is at odds with the Minister’s mandate of supporting northern economic development.”33,p.17

Drawing on data collected by NNC, Galloway31 studied whether or not the existence of the subsidy program made a meaningful difference in the cost of food in northern communities. She found that the lack of retail competition in small communities, even those subsidized by NNC, resulted in extremely high food costs. She provided examples from the Far North, noting that communities with a second retailer still could not be considered a competitive food retail environment, and those communities with a single food retailer exhibited the highest cost of food in Canada.31 In our research, we found that there is a shortage of competition for food retailers in the provincial Norths. We suggest that limited retail competition plays a significant role in food insecurity in northern Canada. Further research is required to obtain data on the oligopoly of the retail food environment in northern Canada and to provide more evidence as to whether a lack of retail competition makes food costs considerably higher in these communities.31 Quantifying the differences in food costs for communities with multiple food retail competitors versus those with oligopolies or monopolies, along with an examination of food quality and further investigation of the perspectives of people living in northern Canada, is warranted.

Strengths and limitations

This paper addresses a relatively unexamined topic in regards to food security in First Nations communities located in the provincial Norths. The paper only examined retail competition in the 120 communities that had NWC stores and did not have year-round road access. The online survey was informed by community members from the FSAG and reflects their concerns about their shopping experiences, and cannot be representative of everyone. The number of survey respondents was limited by several factors: the need for access to the Internet in order to complete the survey, language barriers, and the fact that the most marginal members of the community were unlikely to respond. The result was a small sample size (n = 92) representing eight provinces and territories and not presenting a complete picture of food retail experiences across northern Canada. However, due to the challenging nature of collecting this type of data in remote regions, along with the absence of other data on shopping experiences from residents in northern locales, this study is a first step in building new information on this topic.

The RNFB is a survey tool created by Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada in consultation with Health Canada to monitor the cost of food in remote northern communities. The RNFB is based on average overall consumption for a sample population and contains 67 items (as revised in 2008) and their purchase sizes.32

Conclusion

Food insecurity in northern Canada, especially among First Nations and Inuit people, is a pressing public health problem. Limited retail food competition have exacerbated this issue enormously. In northern Ontario, there is only one full-service grocery store in 91% (20 of 22) of the fly-in First Nations communities that are only accessible by seasonal ice roads. Limited retail choices also affect the range and quality of foods that people are able to purchase. Efforts to support Indigenous food sovereignty must address all elements of local food economies, including retail and land and water harvesting activities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the kindness, generosity and patience shown to us by the community members who worked with us on this project. We also thank Robert Thivierge, who did the legwork of identifying grocery stores in northern Canada, and James Jung, who helped us with some last-minute fact checking. The research was funded by SSHRC.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have an affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interests in the subject matter or materials discussed in this article.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

Authors' contributions

KB and KS were involved in the conceptualization of the work; distribution of the survey; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; and drafting and revising the manuscript. TH was involved in the distribution of the survey; analysis of the data and drafting the manuscript. JL was involved in the conceptualization of the work and the drafting of the online survey and its distribution among community members. LC was involved in the conceptualization of the work and revising the manuscript.

References

- Minaker L, Shuh A, Olstad D, Engler- Stringer R, Black J, Mah C. Retail food environments research in Canada: a scoping review. Can J Public Health. 2016;107((Suppl 1)):eS4–eS13. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.107.5344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power E. Conceptualizing food security for Aboriginal people in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2008;99((2)):95–97. doi: 10.1007/BF03405452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socha T, Chambers L, Zahaf M, Abraham R, Fiddler T. Food availability, food store management, and food pricing in a northern community First Nation community. Int J Humanit Soc Sci. 2011;1((11)):49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Socha T, Zahaf M, Chambers L, Abraham R, Fiddler T. Food security in a northern First Nations community: an exploratory study on food availability and accessibility. J Aborig Health. 2012;((March 2012)):5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner K, Hanning R, Desjardins E, Tsuji L. Giving voice to food insecurity in a remote indigenous community in subarctic Ontario, Canada: traditional ways, ways to cope, ways forward. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:427. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-427. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett K, Skinner K, LeBlanc J. From Food Mail to Nutrition North Canada: reconsidering federal food subsidy programs for northern Ontario. Can Food Stud. 2015;2((1)):141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bell J. Iqaluit (NU):: 2016 Jan 7 [n.p. Parody ad campaign lampoons Nunavut food prices [Internet]. .]; Available from: http://www .nunatsiaqonline.ca/stories/article /65674parody_ad_campaign_lampoons _nunavut_food_prices/ . [Google Scholar]

- Council of Canadian Academies; Ottawa (ON): 2014. Aboriginal food security in northern Canada: an assessment of the state of knowledge. p. 296 p. [Google Scholar]

- De Schutter O. New York (NY):: 2012 [cited 2015 Jan 3]. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Addendum, Mission to Canada [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.srfood.org /images/stories/pdf/officialreports/ 20121224_canadafinal_en.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- McBain L. Pulling up their sleeves and getting on with it: providing healthcare in a northern remote region. Can Bull Med Hist. 2012;29((2)):309–28. doi: 10.3138/cbmh.29.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates K, Poelzer G. Ottawa (ON):: 2014 [cited 2016 Dec 1]. The next northern challenge: the reality of the provincial North [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.macdonaldlaurier .ca/files/pdf/MLITheProvincial North04-14-Final.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S, Kamal AG, Wiebe J. Community development to feed the family in northern Manitoba communities: evaluating food activities based on their food sovereignty, food security, and sustainable livelihood outcomes. Can J Nonprofit Soc Econ Res. 2012;3((2)):43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner K, Hanning RM, Tsuji LJ. Prevalence and severity of household food insecurity of First Nations people living in an on-reserve, sub-Arctic community within the Mushkegowuk Territory. Public Health Nutr. 2013;17((1)):31–9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013001705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The North West Company Inc. The North West Company; Winnipeg (MB): 1988. 1988 Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- The North West Company Inc. The North West Company; Winnipeg (MB): 1990. 1990 Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- Beaumier MC, Ford Food insecurity among Inuit women exacerbated by socio-economic stresses and climate change. Can J Public Health. 2010;101((3)):196–201. doi: 10.1007/BF03404373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Air Stage Subsidy Review (Canada). Indian and Northern Affairs Canada; Hull (QC): 1990. Food for the North: report of the Air Stage Subsidy Review. p. 86 p. [Google Scholar]

- Gulig A. We beg the government: Native people and game regulation in northern Saskatchewan, 1900-1940. Prairie Forum. 2003;28((1)):83. [Google Scholar]

- Tough F. Introduction to documents: Indian hunting rights, natural resources, transfer agreements, and legal opinions from the department of justice. Native Stud Rev. 1995;10((2)):121–149. [Google Scholar]

- Robidoux MA, Imbeault P, Blais JM, et al. Traditional foodways in two contemporary northern First Nations communities. Can J Nat Stud. 2012;32((1)):59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Chan L, Receveur O, Sharp D, Schwartz H, Ing A, Tikhonov C. University of Northern British Columbia; Prince George (BC): 2011. First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study (FNFNES): results from British Columbia (2008/2009). p. 216 p. [Google Scholar]

- Pal S, Haman F, Robidoux M. The costs of local food procurement in two northern Indigenous communities in Canada. Food Foodways. 2013;21((2)):132–52. [Google Scholar]

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Ottawa (ON):: 2016 [cited 2016 Dec 1]. Nutrition North Community eligibility as of October 1, 2016 [Internet]. . Available from: http:// www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca/eng /1415540731169/1415540791407#map . [Google Scholar]

- Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. Ottawa (ON):: 2014 [cited 2017 Jul 12]. 2014 Fall Report of the Auditor General of Canada, Chapter 6 – Nutrition North Canada [Internet]. . Available from: http:// www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English /parl_oag_201411_06_e_39964.html . [Google Scholar]

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Ottawa (ON):: 2016 [cited 2016 Dec 1]. Nutrition North Canada engagement 2016 [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca /eng/1464190223830/1464190397132 . [Google Scholar]

- Veeraraghavan G, Burnett K, Skinner K, et al. Food Secure Canada; Ottawa (ON): 2016. Paying for nutrition: a report on food costing in the North. p. 70 p. [Google Scholar]

- The North West Company; Winnipeg (MB): 2016. Top work, top results: annual information form, year ended January 31st, 2016. p. 37 p. [Google Scholar]

- Nutrition North Canada. Ottawa (ON):: 2016 [cited 2016 May 13]. 2014-2015: Full fiscal year—data per retailer or supplier [Internet]. . Available from: http:// www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca/eng /1453219591740/1453219765675#h6 . [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa (ON):: 2014 [cited 2016 Nov 9]. Northern Food Retail Data Collection and Analysis by Enrg Research Group [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca /eng/1424364469057/1424364505951 . [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa (ON):: [modified 2017 Apr 28; cited 2017 May 7]. Nutrition North Canada engagement 2016: final report of what we heard. [Internet]. . Available from: http://www. nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca/eng /1491505202346/1491505247821 . [Google Scholar]

- Canada’s northern food subsidy Nutrition North Canada: a comprehensive program evaluation. Int J Circumpolar Health [Internet]. Galloway T. 76(1): 1279451 doi: 10.1080/22423982.2017.1279451. . Available from: http:// dx.doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2017 .1279451 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian and Northern Affairs. Ottawa (ON):: 2007 [cited 2017 Jul 12]. The Revised Northern Food Basket [Internet]. . Available from: http://publications.gc .ca/collections/collection_2008/inac -ainc/R3-56-2007E.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Dargo G. Food Mail Program review: findings and recommendations of the Minister’s Special Representative. Yellowknife (NT): Dargo & Associates Ltd. ; 2008:45 p. [Google Scholar]