ABSTRACT

Patients with EGFR mutations showed unfavorable response to programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) blockade immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Yet the underlying association between EGFR mutation and immune resistance remains largely unclear. We performed an integrated analysis of PD-ligand 1(PD-L1)/CD8 expression and mutation profile based on the repository database and resected early-stage NSCLC in Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute (GLCI). Meanwhile, 2 pool-analyses were set to clarify the correlation between EGFR mutation and PD-L1 expression, and the association of EGFR status with response to anti-PD-1/L1 therapy. Pool-analysis of 15 public studies suggested that patients with EGFR mutations had decreased PD-L1 expression (odds ratio: 1.79, 95% CI: 1.10–2.93; P = 0.02). Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the GCLI cohort confirmed the inverse correlation between EGFR mutation and PD-L1 expression. Furthermore, patients with EGFR mutation showed a lack of T-cell infiltration and shrinking proportion of PD-L1+/CD8+ TIL (P = 0.034). Importantly, patients with EGFR mutations, especially the sensitive subtype, showed a significantly decreased mutation burden, based on analysis of the discovery and validation sets. Finally, a pool-analysis of 4 randomized control trials confirmed that patients with EGFR mutation did not benefit from PD-1/L1 inhibitors (Hazard ratio [HR] = 1.09, P = 0.51) while patients with EGFR wild-type did (HR = 0.73, P < 0.00001). This study provided evidence of a correlation between EGFR mutations and an uninflamed tumor microenvironment with immunological tolerance and weak immunogenicity, which caused an inferior response to PD-1 blockade in NSCLCs.

KEYWORDS: EGFR, mutation burden, non-small cell lung cancer, programmed cell death protein-1, uninflamed

Introduction

Two major treatment paradigms have been recently established for the management of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs): targeted therapies based on the inhibition of aberrant oncogenic drivers and immunotherapies based on the blocking of immunosuppressive checkpoints. Although patients with NSCLC and an oncogenic mutation in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) most likely benefit from EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), they eventually develop therapeutic resistance.1,2 It is not known whether a patient harboring an EGFR mutation will be equally suitable for treatment with checkpoint inhibitors in the initial or resistant scenario.

Recent studies have reported that aberrant EGFR, KRAS and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) signaling drives the expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1).3-5 In vitro therapy with PD-1 inhibitors in EGFR mutant and ALK rearranged tumor co-culture systems with immune cells and compromised tumor cell viability.3,5-7 Furthermore, treatment with a PD-1 inhibitor in EGFR mutant mouse models improved their survival rates.6 These preclinical findings indicated the superiority of patients with EGFR mutations treated with PD-1/L1 blockade immunotherapy. However, recent clinical trials have revealed an opposite result; patients with EGFR mutation manifested poorer response to PD-1/L1 inhibitors than those with EGFR wild-type.8-11 A retrospective analysis performed by Dr. Gainor and colleagues12 had revealed that EGFR mutations were associated with low response rates to PD-1 blockade in NSCLCs. These paradoxical results from preclinical studies and clinical practice reveal a confusing relationship between EGFR mutation and the immune microenvironment and immunotherapeutic response.

In the study by Dr. Gainor et al.,12 patients with EGFR mutation did not show an inflamed tumor microenvironment (TME), which results from a lack of CD8-positive tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. In addition, EGFR mutations frequently occurred in patients without a history of smoking, indicating a lower tumor mutation burden (TMB) in this subgroup. Here, we tried to elucidate the underlying mechanisms that account for EGFR mutation-mediated immune evasion. We described an integrative analysis, incorporating PD-L1 expression, content of CD8+ T cell infiltration, and TMB from cohorts of repository and internal databases, as well as resected NSCLC specimens. Significantly, we uncovered EGFR mutations were correlated with uninflamed TME with immunological tolerance and weak immunogenicity, which resulted in the inferior response to PD-1 blockade.

Results

EGFR mutations are inversely correlated with PD-L1 expression in NSCLCs

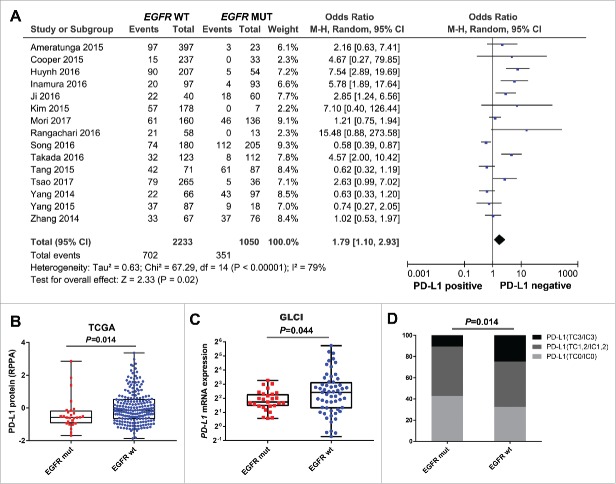

To investigate the correlation between EGFR mutation and immune checkpoint status in NSCLC, we first performed a pool-analysis to systematically assess the association between EGFR mutation and PD-L1 expression. Results of 3283 patients from 15 studies were analyzed. As shown in the forest plot, EGFR wild-type tumors were more likely to be PD-L1-positive than EGFR mutant tumors (OR: 1.79; 95% CI 1.10–2.93; P = 0.02; I2 = 0, P = 0.67; Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Correlation between EGFR mutation and PD-L1 expression in patients with NSCLC (A) Forest plot of 15 studies evaluating the association between EGFR status and PD-L1 expression. Pooled odds ratio (OR) were computed using random-effects model. (B) Quantitative analysis of PD-L1 protein derived from reverse phase protein array based on EGFR status. (C) Quantitative analysis of PD-L1 mRNA expression from RNA-Seq profile of patients in Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute (GLCI) based on EGFR status. (D) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis of PD-L1 protein expression based on EGFR status in a cohort of 255 resected NSCLC. mut, mutation; wt, wild-type

To confirm the results of this pool-analysis, we analyzed the protein and mRNA profiles of PD-L1 in the repository (The Cancer Genome Atlas; TCGA) and internal (Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute; GLCI) databases; we also performed IHC detection of PD-L1 in resected NSCLC tissues. Reverse-phase protein array (RPPA) analysis consisted of 237 lung adenocarcinomas from TCGA cohort showed that EGFR mutant tumors were correlated with decreased expression of PD-L1 protein, compared with EGFR wild-type tumors (P = 0.014; Fig. 1B). Analysis of mRNA profiles in the GLCI cohort also showed that patients with EGFR mutations had lower PD-L1 expression than those with EGFR wild-type (P = 0.044; Fig. 1C). Furthermore, we analyzed 255 resected NSCLC samples in our center with IHC detection of PD-L1 and Sanger sequencing of EGFR. The results showed a significantly higher proportion of strongly positive for PD-L1 (TC3/IC3) in the EGFR wild-type group than in the mutation group, indicating an inverse correlation between EGFR mutation and PD-L1 expression (P = 0.014; Fig. 1D).

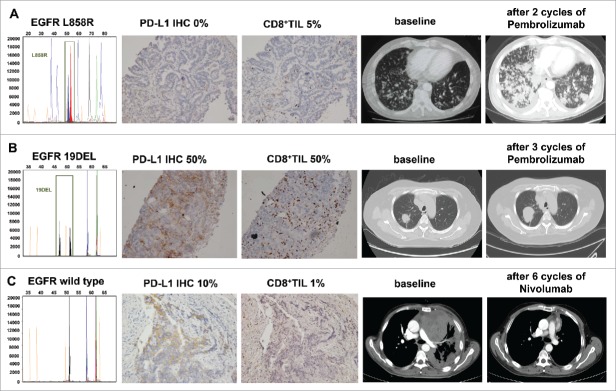

EGFR mutations show a lack of T-cell infiltration and present immunological tolerance

The presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) is an important predictive factor for response to PD-1 blockade immunotherapy. We then explored the correlation between EGFR status and CD8+ T-cell infiltration. Analysis of mRNA profiles in the GLCI cohort indicated that patients with EGFR mutations had a lower CD8A expression than those with EGFR wild-type (P = 0.031; Fig. 2A). Furthermore, IHC analysis of CD8+ TILs in the 255 resected NSCLC specimens confirmed that EGFR mutant tumors showed lesser T-cell infiltration than EGFR wild-type ones (P = 0.003; Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

EGFR mutant tumors show a lack of T-cell infiltration and low shrink proportion of PD-L1+/CD8+ TILs (A) Quantitative analysis of CD8A mRNA expression from RNA-Seq profiles of GLCI, based on EGFR status. (B) IHC analysis of CD8+ T lymphocytes infiltration, based on EGFR status in resected NSCLCs. (C and D) The correlation between EGFR status and tumor microenvironment immune phenotype classified based on PD-L1 and CD8A/CD8+ TIL expression, from the GLCI RNA-Seq data and IHC analysis. (E) Representative images of PD-L1 and CD8 immunostaining in resected NSCLC samples, based on EGFR status. dual-positive for PD-L1 and CD8A (PD-L1+/CD8A+) were defined as above-median mRNA expression for each gene. PD-L1+/CD8+ TIL was defined as PD-L1: TC2–3/IC2–3 and CD8 ≥ 25%. mut, mutation; wt, wild-type.

A previous study had classified immune microenvironments into 4 groups based on PD-L1 expression and TIL recruitment.13,14 We then determined whether EGFR status affected the tumor immune microenvironment. In the GLCI cohort, the EGFR mutant group showed a remarkably higher proportion of PD-L1−/CD8A− and lower proportion of PD-L1+/CD8A+ than the EGFR wild-type group (P < 0.001; Fig. 2C). The combined analysis of PD-L1 and CD8+ TIL in the IHC-detected group showed a significantly shrinking proportion of dual-positive (PD-L1+/CD8+ TIL), while an increased proportion of dual-negative (PD-L1−/CD8−TIL) was observed in the EGFR mutant group (P = 0.005; Fig. 2D, 2E), suggesting an uninflamed phenotype with immunological tolerance.

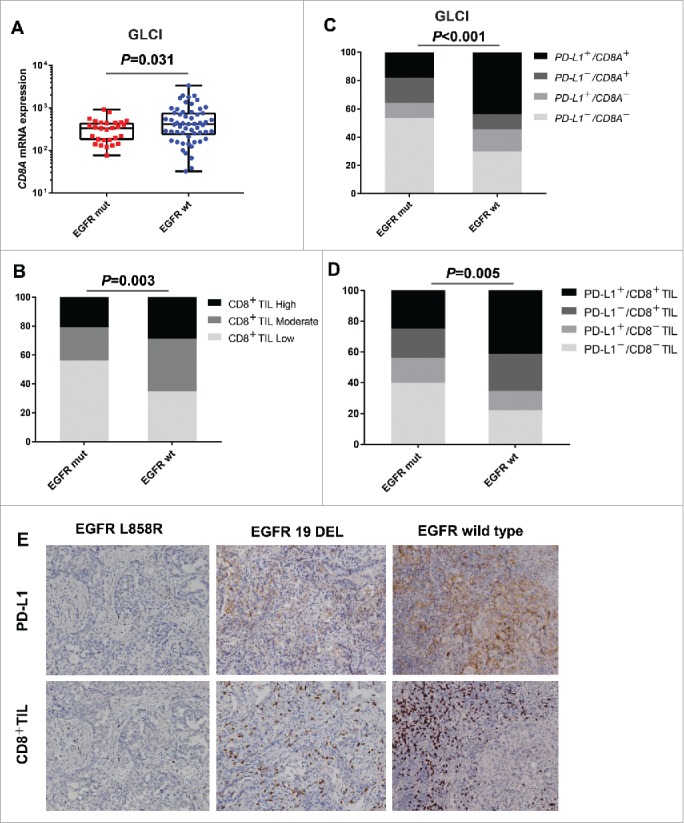

Patients with sensitive EGFR mutation display low immunogenicity

Recent studies have highlighted the relevance of tumor mutation burden (TMB) in the response to PD-1 blockade.15 Therefore, we explored the relationship between EGFR mutational status and the TMB. We analyzed the mutation profiles in TCGA and the Broad database as the discovery set. The data from TCGA showed a significantly reduced mutational burden in the EGFR-mutant group (median: 56), compared with the wild-type group (median: 181, P < 0.001; Fig. 3A). We then tested these findings using another data set (Broad), and the results confirmed that patients with EGFR mutation had lower TMB (median: 59) than those with EGFR wild-type (median: 209; P = 0.003; Fig. 3B). To strengthen these findings, 85 lung adenocarcinomas from the GLCI were subjected to whole genome sequencing, and defined as the validation set. The GLCI data showed results similar to those of the discovery set, i.e., the EGFR mutant group (median: 162) had lower TMB than the EGFR wild-type group (median: 197; P = 0.029; Fig. 3C). We next investigated whether EGFR mutations affected the tumor mutation spectrum, which represents the rate of transition and transversion. Not surprisingly, both the Broad cohort (P = 0.002) and the GLCI cohort (P < 0.001) showed that tumors with EGFR mutations manifested a decreased rate of transversion/transition, which was consistent with the reduced TMB in this group (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 3.

EGFR mutation is correlated with decreased immunogenicity (A and B) Quantitative analysis of tumor mutational burden in EGFR mutation and wild-type tumors in the discovery set (TCGA and Broad cohorts). (C) Difference in tumor mutational burden based on EGFR status in the validation set (GLCI cohort). (D and E) Subgroup analysis of tumor mutational burdens between tumors with sensitive and resistant/unknown EGFR mutations in TCGA and Broad cohorts. mut, mutation; wt, wild-type; S-mut, sensitive mutation; R/UNK-mut, resistance/unknown sensitive mutation.

It is well known that EGFR mutations are far from pure events. Based on the response to 1st-generation EGFR-TKI, EGFR mutations can be classified as sensitive and resistant mutations. This raises the question of whether alterations in TMB resulted from EGFR mutations should be treated differently. Interestingly, we had found a significant difference in TMB between EGFR-sensitive (exon 19Del, L858R, L861Q, G719X, S768I)16-18 and EGFR-resistant/unknown mutations, based on the analysis of the TCGA cohort; the EGFR-sensitive mutant group showed a significantly lower TMB than the resistant/unknown group (median: 60 vs. 283; P < 0.001; Fig. 3D). Similarly, analysis of the Broad cohort confirmed that tumors with a sensitive EGFR mutation displayed significantly lower TMB than those with resistant/unknown mutations (59 vs. 159; P = 0.042; Fig. 3E), indicating it was the sensitive EGFR mutation that accounted for a low immunogenicity in NSCLC.

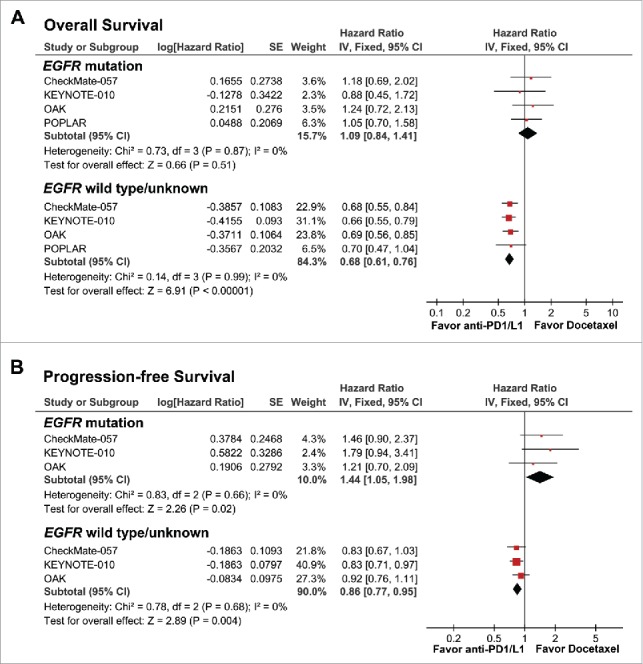

Patients with EGFR mutant NSCLC show impaired response to PD-1 blockade

Given that EGFR mutation was correlated with immunological tolerance and low immunogenicity, we speculated that EGFR mutation might be a negative predictive factor for PD-1 blockade immunotherapy in patients with NSCLC. A pool-analysis was performed to assess the different efficacy in NSCLC patients with EGFR mutant and wild-type comparing second-line PD-1/L1 inhibitor with docetaxel. Results from 2752 patients from 4 randomized control trials were analyzed. As expected, patients with EGFR mutation did not benefit from PD-1/L1 inhibitors in overall survival (OS; HR, 1.09, 95% CI [0.84–1.41]; P = 0.51) and even worse than docetaxel in progression-free survival (PFS; HR, 1.44, 95% CI [1.05–1.98]; P = 0.02). Conversely, patients with EGFR wild-type benefited most from PD-1/L1 inhibitors compared with docetaxel in both OS (HR, 0.67, 95% CI [0.61–0.76]; P<0.001) and PFS (HR, 0.86, 95% CI [0.77–0.95]; P = 0.004) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plots of hazard ratios (HRs) for (A) overall survival (OS) and (B) progression-free survival (PFS) from 4 randomized control trials, comparing second-line PD-1/L1 inhibitor with docetaxel in patients with EGFR mutations and wild-type non-small cell lung cancer. Pooled HRs were computed using the fixed-effects model.

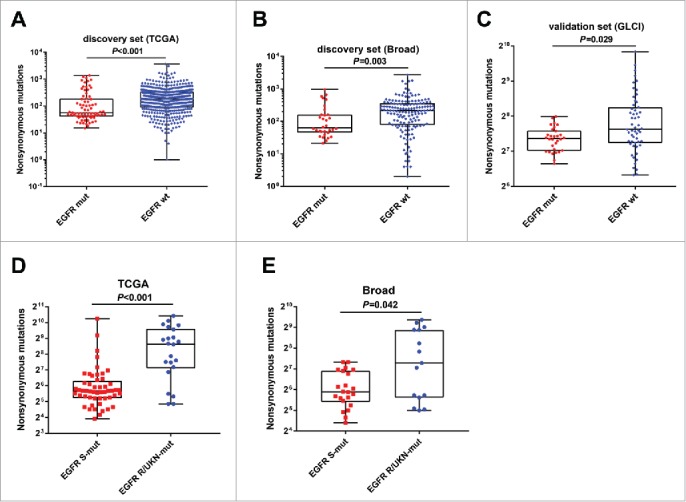

Next, we focused on 3 representative cases from our center treated with PD-1 inhibitors. Patient A was a heavy-smoking male diagnosed with lung adenocarcinoma (cT4N3M1c, stage IVB), harboring an EGFR L858R mutation, who showed PD-L1-negative expression and low density of CD8+ TIL. After 2 cycles of pembrolizumab treatment, the patient was evaluated as dramatic progression and performance deterioration (Fig. 5A). Patient B was a non-smoking female diagnosed with lung squamous cell carcinoma (cT1bN0M1b, stage IVB) with an EGFR exon 19 deletion. She was strongly positive for PD-L1 (PD-L1 = 50%) and CD8+ TIL (CD8 = 50%). However, after 3 cycles of pembrolizumab treatment, the patient hardly showed any clinical benefits, and directly produced a progression disease (+120%) (Fig. 5B). Patient C was a light-smoking male diagnosed with lung squamous cell carcinoma (cT4N2M1a, stage IVA). He was enrolled in the CheckMate 078 clinical trial, had EGFR wild-type, was moderately positive for PD-L1 (PD-L1 = 10%), and showed a weak density of CD8+ TIL. After 6 cycles of nivolumab treatment, the patient was found to show a partial response (−90%) (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Anti-tumor activity and biomarker analysis of EGFR and PD-L1 in 3 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 inhibitors (A, B, and C).

Discussion

With the emergence of checkpoint-focused clinical trials for NSCLC, there is an increasing concern about the significance of driver mutations in guiding immunotherapy. This study was aimed to extend our understanding of the potential mechanisms behind immune evasion in patients with EGFR mutation. We performed an integrated study, and showed that EGFR mutation was correlated with decreased PD-L1 expression, lack of T-cell infiltration, and lower TMB. These 3 factors were previously shown to be predictive biomarkers for PD-1 blockade immunotherapy.19 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically explore the underlying mechanisms behind the association between EGFR mutation and immune resistance, which to some extent, explains why NSCLC patients with positive EGFR mutation respond poorly to PD-1/L1 inhibitors. This study was performed as an integrated investigation based on pooled analysis of randomized control trials and large-sample analyses, with whole genome sequencing from both repository databases (TCGA and Broad) as well as samples from the GLCI, which enhanced the reliability of our conclusions.

In this study, we found that patients harboring EGFR-activating mutations showed a lower PD-L1 expression than those with EGFR wild-type. Our results are different from those of some previous studies, which argued that EGFR mutation increased the expression of PD-L1.6,20,21 This discrepancy is likely due to the heterogeneity of the study populations. Our recent published study had demonstrated some common mutations (KRAS/TP53/STK11) significantly affected the PD-L1 expression.22 Therefore, it is reasonable to understand the co-mutated genes in the patients with EGFR mutation. Furthermore, various antibodies and cut-off values have been reported for immunohistochemically evaluating PD-L1 expression, which may lead to conflicting results.23,24 In addition, previous studies have focused on the correlation between EGFR status and PD-L1 expression, but they overlooked the TILs and TMB of which the impact may interfere in EGFR mutant patients. This might partly explain why some patients with EGFR mutation and PD-L1–positive failed to respond to anti-PD-1/L1 therapy. In contrast, our study comprehensively analyzed the association between EGFR mutation and PD-L1 expression, CD8-positive T-cell infiltration, and TMB, and thus better interpreted the relationship between EGFR mutation and immune evasion.

Given that EGFR mutations affected several immune-related biomarkers and induced an immunosuppressive TME, we speculated on the element that served as the chief culprit for PD-1 blockade in patients with EGFR mutation. Previous studies have suggested that optimal activation of effector T cells required 2 signals: an antigen-specific signal generated by the interaction between the antigen and the TCR (MHC-Ag- TCR) and a second signal resulting from the interaction between costimulatory molecules (B7-CD27).25,26 We showed in this study that EGFR mutations caused a weakening of the immunogenicity, which impaired the antigen specific signal and caused the T cells to become blind to the tumor cells. As we all know, the CheckMate 026 clinical trial comparing first-line nivolumab with standard chemotherapy in NSCLC patients with PD-L1≥ 5% was failed. However, a recent exploratory analysis of CheckMate 026, based on the subgroup of TMB, showed promising results. Patients in the high-TMB subset demonstrated significantly prolonged PFS and superior ORR, indicating that TMB may be a preferable predictive biomarker for anti-PD1/L1 therapy. In our study, we reported 3 patients, who had undergone PD-1 inhibitors therapy. Remarkably, patient B had an EGFR exon 19 deletion and was strongly positive for PD-L1 (PD-L1 = 50%) and CD8+ TIL (CD8 = 50%). However, after 3 cycles of pembrolizumab treatment, the patient hardly showed any clinical benefits, but exhibited progression disease, implying that the low TMB induced by EGFR mutation may be the primary reason for the lack of response.

In Asian populations, the incidence of EGFR mutation was estimated to be 39.6% in NSCLC, and even exceeded 50% in adenocarcinoma.27 After obtaining the possible reasons for EGFR-mediated immune escape, we speculated upon how to manage EGFR-mutant patients with TKI resistance in the setting of immunotherapy. Recent clinical trials of checkpoint-based combination therapies have highlighted the potential to enhance the clinical benefits of monotherapies by combining them with agents that have synergistic activities.28,29 Preclinical data have shown that radiotherapy sensitized refractory tumors to checkpoint inhibitors by recruiting antitumor T cells and converting “cold” tumors into “hot” ones. More importantly, radiotherapy was shown to induce T cell responses to peptides derived from proteins upregulated in response to radiation, suggesting that radiation could expose antigenic mutations that were silent in non-irradiated tumors.30,31 Recently, a study on secondary analysis of the KEYNOTE-001 had discovered an interesting result: previous treated with radiotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC resulted in longer PFS and OS with pembrolizumab treatment than that seen in patients who did not have previous radiotherapy.32 Notably, there are 54 patients with NSCLC and EGFR mutation in KEYNOTE-001, it is worth investigating the response of this subgroup with or without radiotherapy.

Our study has several limitations. First, we did not consider the situations in which patients with EGFR mutation will respond to anti-PD-1/L1 therapy. A recent clinical trial identified a small group of patients with EGFR mutations, who have acquired partial response and longer PFS during treatment. Future studies should focus on this population and explore the underlying mechanism behind this improved efficacy. Second, although we demonstrated that the EGFR mutation-induced immune resistance was due to reduced PD-L1 expression, lack of CD8+ T cell infiltration, and lower TMB, we could not estimate definite cut-off values for these 3 continuous variables; thus, we still cannot identify patients with EGFR mutations who are likely to respond to PD-1/L1 inhibitors. These cutoff values need to be defined and then clinically validated.

In conclusion, the results of this study highlighted an insight into the underlying mechanisms between EGFR mutation and immune evasion. We identified those patients with EGFR mutation showed impaired response to PD-1 pathway blockade, which could be due to the uninflamed TME with immunological ignorance and weak immunogenicity.

Materials and methods

We extracted mRNA expression profiling data from TCGA database or from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) in GLCI. The data was analyzed for the mRNA expression of PD-L1 and CD8A. Reverse phase protein array (RPPA) and immunohistochemistry was performed for estimating PD-L1 protein and CD8+ TIL content. Mutation profiling data extracted from repository databases (TCGA and Broad) and the WGS data was analyzed for TMB.

Clinical cohorts

TCGA and Broad cohorts were retrieved from the online data repository. The gene mutational profiles of 542 lung adenocarcinoma patients were included in TCGA cohort. The Broad cohort contained 183 lung adenocarcinomas and matched normal tissues with detailed information about mutation load and mutation spectrum.33 A total of 85 lung adenocarcinoma samples from the GLCI, Guangdong General Hospital (GGH) were subjected to WGS and mRNA expression profile analysis. Another cohort from GLCI consisted of NSCLC samples resected from 255 patients from January 2010 to December 2012, which were analyzed for PD-L1 expression and EGFR status. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of GLCI of GGH, and all patients provided specimens with written informed consent. The key variables of these 4 cohorts, including demographic and clinical information, are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Pool-analyses

The first pool-analysis focused on the correlation between PD-L1 expression and EGFR status in resected NSCLC samples. The results of 3283 patients from 15 studies were analyzed. The characteristics of the included patients, including race, staging, PD-L1 antibody clone, and cut-off value, are summarized in Supplementary Table S2.

The second pool-analysis compared the efficacy of a second-line PD-1/L1 inhibitor with that of docetaxel in patients with metastatic NSCLC with mutated or wild-type EGFR. The results of 2752 patients from 4 randomized control trials (CheckMate-057, keynote-010, OAK, POPLAR)8-10,34 were analyzed. The baseline characteristics of the enrolled trials are summarized in the Supplementary Table S3.

Data extraction was performed independently by 2 authors (ZYD and SYL) from the eligible studies using a predefined information sheet. Study design, search strategy, and selection criteria of these above 2 pool-analyses are provided in Supplemental Methods and Fig. S2, S3.

Reverse-phase protein array (RPPA) and mRNA expression profiling analysis

Proteomic analysis was based on RPPA from TCGA database, comprising 237 lung adenocarcinomas. The RPPA methodology and data analysis pipeline have been described in a previous study.35 The RPPA data were downloaded directly from TCGA portal and used in subsequent analyses.

For mRNA expression sequencing in the GLCI cohort, the experimental procedures for RNA extraction from tumors, mRNA library preparation, sequencing (Illumina HiSeq 2000), quality control, and subsequent data processing for quantification of gene expression have been previously reported.35 Cufflinks v2.0.2 uses the normalized RNA-seq fragment counts to measure the relative abundance of transcripts.36 Gene expression levels were calculated in terms of fragments per kilo base of exon model per million mapped reads (FPKM).

Mutation data analysis

For the discovery set, somatic mutation data (level 2) of the 542 lung adenocarcinomas were retrieved from TCGA data portal (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/findArchives.htm) and The Cancer Immunome Atlas (TCIA) (https://tcia.at/). To assess the mutational load, the number of mutated genes carrying at least one non-synonymous mutation in the coding region was computed for each tumor. The somatic mutation data of the Broad cohort was retrieved from cbioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/study.do?cancer_study_id=luad_broad). The whole list of 6 base substitutions and numerical mutation burden was provided for all 183 lung adenocarcinomas.

For the validation set (GLCI), whole-genome sequencing of DNA from tumors and matched normal blood were conducted for 85 patients with lung adenocarcinoma in our center. Enriched exome libraries were sequenced on the HiSeq 2000 platform (Illumina) to >100 coverage. Alignment, base-quality score recalibration, and duplicate-read removal were performed; germline variants were excluded; mutations were annotated; and indels were evaluated as described previously.15,37

The mutation spectrum for each sample in the Broad and GLCI cohorts was calculated as the percentage of each of 6 single nucleotide changes, including base transitions (AT > GC and GC > AT) and base transversions (AT > CG, AT > TA, GC > CG, and GC > TA), among all the single nucleotide substitutions.

Immunohistochemistry

Tumor sections were assessed immunohistochemically using PD-L1 (clone: SP142, Spring Bioscience, Inc.) and CD8 (clone: C8/144B, Gene Tech Co., Ltd). The IHC-stained tissue sections were scored separately by 2 pathologists (LXY and YFL), who were blinded to the clinical parameters. PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and immune cells was evaluated using a 3-tiered grading system. Strong: ≥50% for tumor cell (TC) or ≥10% for immune cell (IC); weak: 5–49% for TC or 5–9% for IC; negative: <5% for TC or IC. The percentage of CD8+ lymphocytes among all the nucleated cells in the stromal compartments was assessed. Scoring cut-off points were set at 25% or 50% for each core, according to the degree of cell densities: low density: <25%; moderate density: 25–49%; high density: ≥50%.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager Version 5.2 (RevMan, Cochrane Collaboration), GraphPad Prism (version 7.01), and SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS, Inc.). Statistical heterogeneity in the pool-analyses was evaluated using the χ2 test and inconsistency index (I2); values were considered significant when χ2 p-value < 0.1 or I2 > 50%. In the absence of statistically significant heterogeneity, the fixed-effect model was used for the pool-analysis. Otherwise, the random-effect model was selected. Scatter dot plot and box and whisker plots indicate median and 95% confidence interval (CI). Mann-Whitney U and Chi-square tests were used to analyze immune-related parameters between EGFR mutation and wild-type groups. All reported P values were 2-tailed, and for all analyses, P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant, unless otherwise specified.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This study was supported by the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Lung Cancer Translational Medicine (Grant No. 2012A061400006), The National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2016YFC1303800), the Special Fund for Research in the Public Interest from the National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China (Grant No. 201402031), the Project of National Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 81372285 and 81673031), and National Natural Science Foundation for Young Scientists of China (Grant No. 81201855).

References

- 1.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, Janne PA, Kocher O, Meyerson M, Johnson BE, Eck MJ, Tenen DG, Halmos B. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:786-92. PMID:15728811. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, Sunpaweravong P, Han B, Margono B, Ichinose Y, et al.. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:947-57. PMID:19692680. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen N, Fang W, Zhan J, Hong S, Tang Y, Kang S, Zhang Y, He X, Zhou T, Qin T, et al.. Upregulation of pd-l1 by egfr activation mediates the immune escape in egfr-driven NSCLC: Implication for optional immune targeted therapy for NSCLC patients with egfr mutation. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10:910-23. PMID:25658629. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen N, Fang W, Lin Z, Peng P, Wang J, Zhan J, Hong S, Huang J, Liu L, Sheng J, et al.. KRAS mutation-induced upregulation of PD-L1 mediates immune escape in human lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2017;PMID:28451792. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2005-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong S, Chen N, Fang W, Zhan J, Liu Q, Kang S, He X, Liu L, Zhou T, Huang J, et al.. Upregulation of PD-L1 by EML4-ALK fusion protein mediates the immune escape in ALK positive NSCLC: Implication for optional anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune therapy for ALK-TKIs sensitive and resistant NSCLC patients. Oncoimmunology 2016; 5:e1094598. PMID:27141355. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1094598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akbay EA, Koyama S, Carretero J, Altabef A, Tchaicha JH, Christensen CL, Mikse OR, Cherniack AD, Beauchamp EM, Pugh TJ, et al.. Activation of the PD-1 pathway contributes to immune escape in EGFR-driven lung tumors. Cancer Discov 2013; 3:1355-63. PMID:24078774. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gettinger S, Politi K. PD-1 Axis inhibitors in EGFR- and ALK-driven lung cancer: Lost cause? Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22:4539-41. PMID:27470969. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, et al.. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1627-39. PMID:26412456. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, Molina J, Kim JH, Arvis CD, Ahn MJ, et al.. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387:1540-50. PMID:26712084. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, Park K, Ciardiello F, von Pawel J, Gadgeel SM, Hida T, Kowalski DM, Dols MC, et al.. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): A phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 389:255-65. PMID:27979383. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CK, Man J, Lord S, Links M, Gebski V, Mok T, Yang JC. Checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer-a meta-analysis. J Thorac Oncol 2017; 12:403-7. PMID:27765535. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gainor JF, Shaw AT, Sequist LV, Fu X, Azzoli CG, Piotrowska Z, Huynh TG, Zhao L, Fulton L, Schultz KR, et al.. EGFR mutations and alk rearrangements are associated with low response rates to pd-1 pathway blockade in non-small cell lung cancer: A retrospective analysis. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22:4585-93. PMID:27225694. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-3101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taube JM, Anders RA, Young GD, Xu H, Sharma R, McMiller TL, Chen S, Klein AP, Pardoll DM, Topalian SL, et al.. Colocalization of inflammatory response with B7-h1 expression in human melanocytic lesions supports an adaptive resistance mechanism of immune escape. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4:127ra37. PMID:22461641. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teng MW, Ngiow SF, Ribas A, Smyth MJ. Classifying cancers based on t-cell infiltration and PD-L1. Cancer Res 2015; 75:2139-45. PMID:25977340. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, Lee W, Yuan J, Wong P, Ho TS, et al.. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 2015; 348:124-8. PMID:25765070. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castellanos E, Feld E, Horn L. Driven by mutations: The predictive value of mutation subtype in egfr-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 12(4):612-623. PMID:28017789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J, Haber DA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7:169-81. PMID:17318210. doi: 10.1038/nrc2088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massarelli E, Johnson FM, Erickson HS, Wistuba II, Papadimitrakopoulou V. Uncommon epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non-small cell lung cancer and their mechanisms of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors sensitivity and resistance. Lung Cancer 2013; 80:235-41. PMID:23485129. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, Pardoll DM. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2016; 16:275-87. PMID:27079802. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azuma K, Ota K, Kawahara A, Hattori S, Iwama E, Harada T, Matsumoto K, Takayama K, Takamori S, Kage M, et al.. Association of PD-L1 overexpression with activating EGFR mutations in surgically resected nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2014; 25:1935-40. PMID:25009014. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang CY, Lin MW, Chang YL, Wu CT, Yang PC. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in surgically resected stage I pulmonary adenocarcinoma and its correlation with driver mutations and clinical outcomes. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50:1361-9. PMID:24548766. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong ZY, Zhong WZ, Zhang XC, Su J, Xie Z, Liu SY, Tu HY, Chen HJ, Sun YL, Zhou Q, et al.. Potential predictive value of TP53 and KRAS mutation status for response to PD-1 blockade immunotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23:3012-24. PMID:28039262. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsao MS, Le Teuff G, Shepherd FA, Landais C, Hainaut P, Filipits M, Pirker R, Le Chevalier T, Graziano S, Kratze R, et al.. PD-L1 protein expression assessed by immunohistochemistry is neither prognostic nor predictive of benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in resected non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(4):882-9. PMID:28137741. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huynh TG, Morales-Oyarvide V, Campo MJ, Gainor JF, Bozkurtlar E, Uruga H, Zhao L, Gomez-Caraballo M, Hata AN, Mark EJ, et al.. Programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in resected lung adenocarcinomas: Association with immune microenvironment. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11:1869-78. PMID:27568346. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.08.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science 2015; 348:56-61. PMID:25838373. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki H, Owada Y, Watanabe Y, Inoue T, Fukuharav M, Yamaura T, Mutoh S, Okabe N, Yaginuma H, Hasegawa T, et al.. Recent advances in immunotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014; 10:352-7. PMID:24196313. doi: 10.4161/hv.26919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yatabe Y, Kerr KM, Utomo A, Rajadurai P, Tran VK, Du X, Chou TY, Enriquez ML, Lee GK, Iqbal J, et al.. EGFR mutation testing practices within the asia pacific region: Results of a multicenter diagnostic survey. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10:438-45. PMID:25376513. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ott PA, Hodi FS, Kaufman HL, Wigginton JM, Wolchok JD. Combination immunotherapy: A road map. J Immunother Cancer 2017; 5:16. PMID:28239469. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0218-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teng F, Kong L, Meng X, Yang J, Yu J. Radiotherapy combined with immune checkpoint blockade immunotherapy: Achievements and challenges. Cancer Lett 2015; 365:23-9. PMID:25980820. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reits EA, Hodge JW, Herberts CA, Groothuis TA, Chakraborty M, Wansley EK, Camphausen K, Luiten RM, de Ru AH, Neijssen J, et al.. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J Exp Med 2006; 203:1259-71. PMID:16636135. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franceschini D, Franzese C, Navarria P, Ascolese AM, De Rose F, Del Vecchio M, Santoro A, Scorsetti M. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy: Can this combination change the prognosis of patients with melanoma brain metastases? Cancer Treat Rev 2016; 50:1-8. PMID:27566962. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaverdian N, Lisberg AE, Bornazyan K, Veruttipong D, Goldman JW, Formenti SC, Garon EB, Lee P. Previous radiotherapy and the clinical activity and toxicity of pembrolizumab in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: A secondary analysis of the KEYNOTE-001 phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18(7):895-903. PMID:28551359. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30380-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imielinski M, Berger AH, Hammerman PS, Hernandez B, Pugh TJ, Hodis E, Cho J, Suh J, Capelletti M, Sivachenko A, et al.. Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing. Cell 2012; 150:1107-20. PMID:22980975. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, Kowanetz M, Vansteenkiste J, Mazieres J, Park K, Smith D, Artal-Cortes A, Lewanski C, et al.. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): A multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387:1837-46. PMID:26970723. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00587-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014; 511:543-50. PMID:25079552. doi: 10.1038/nature13385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Feng Z, Wang X, Wang X, Zhang X. DEGseq: An r package for identifying differentially expressed genes from rna-seq data. Bioinformatics 2010; 26:136-8. PMID:19855105. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan TA, Wolchok JD, Snyder A. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1984. PMID:26559592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1508163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.