Abstract

We explore the impact of malpractice caps on non-economic damages that were enacted between 2003 and 2006 on the supply of physician labor, separately for high-malpractice risk and low-malpractice risk physician specialty types, and separately by young and old physicians. We use physician data from the Area Resource File for 2000–2011 and malpractice policy data from the Database of State Tort Law Reforms. We study the impact of these caps using a reverse natural experiment, comparing physician supply in nine states enacting new caps to physician supply in ten states that had malpractice caps in place throughout the full time period. We use an event study to evaluate changes in physician labor compared to the prior year. We find evidence that non-economic damage caps increased the supply of high-risk physicians <35 years of age by 0.93 physicians per 100,000 people in the year after the caps were enacted. Non-economic damage caps were cumulatively associated with an increase of 2.1 high-risk physicians <35 years of age per 100,000 people. Stronger non-economic damage caps generally had a larger impact on physical supply.

Keywords: malpractice, physician labor supply

Introduction

Physician labor supply has long-standing importance for access to and quality of healthcare delivered in the United States.1–7 One potential driver of regional physician shortages is that some physicians may not want to practice in states that have unfavorable malpractice laws because they may be forced to pay higher malpractice premiums or may feel they are at higher risk for being sued.8,9 Physicians may choose the state in which they practice based on malpractice environment, or they may choose to leave the workforce entirely by retiring, for example. This may be particularly true for high-risk specialists such as surgical subspecialties and obstetrics/gynecology.9,10

In an effort to improve the malpractice environment for physicians, states have responded by passing laws to reduce the risk of a malpractice lawsuit and malpractice payouts.8,11–16 Malpractice reforms can be divided into indirect and direct reforms. Indirect reforms include those that limit access to court, such as statutes of limitations and screening panels, and include reforms that require higher standards of proof, such as expert witness standards.11 Direct reforms are those that limit the size of awards, also known as damage caps. Physician groups have long argued that physicians want to practice in states with damage caps, and that caps reduce regional physician shortages.8 Increased physician supply in states with damage caps may be a beneficial effect – whether intended or not.8,17–20

There have been three major waves of malpractice reforms: in the mid-1970s, mid-1980s, and mid-2000s. In the most recent wave of reforms, known as the third wave, eleven states instituted damage caps between the years of 2003 to 2006.21 One recent article by Helland and Seabury22 used a difference-in-difference model to compare the supply of physicians in states adopting damage caps in the third wave of reform, pre- and post-adoption. The authors noted non-parallel time trends that caused omitted variable bias in this difference-in-difference analysis; therefore, they addressed this by performing a difference-in-difference-in-difference (DDD) analysis that compared the supply of high-risk specialists relative to low-risk specialties in the states enacting malpractice reform. The authors found that the supply of high-risk specialists increased relative to low-risk specialists in adopting states. The authors noted that one of the limitations of a DDD methodology is that it prevents drawing conclusions about the impact of reforms on overall physician supply, which may be more directly relevant to local policy debates.

Paik, Black, and Hyman23 also explored the effects of the third wave of malpractice reform. In their analysis the authors primarily used as the control group only states without caps on non-economic damages, but in supplementary analyses they also calculate results using a “broader” control group of all states (both non-adopting states and prior-adopting states). The authors found no evidence that cap adoption led to an increase in specialties that face high liability risks with the exception of plastic surgeons. In our study, we use an alternative control group of states having previously adopted non-economic damage caps. We also explore heterogeneity by physician age, which the authors did not do in their study.

Other studies have explored the earlier two waves of malpractice reforms. Encinosa and Hellinger found that physician supply increased by over 2 percent in states that had instituted damage caps between 1985 and 2000 and also found that the supply of obstetricians/gynecologists and surgeons increased by over 5 percent in states with damage caps of $250,000 or less.24 Kessler et al. found a 3.3 percent increase in physician supply in states that had instituted caps between 1985 and 2001 compared with states that had not.25

This current study uses the third wave of malpractice reform and explores the age at which physician supply is most sensitive to non-economic damage caps. We hypothesize that physician supply, particularly supply of high-risk specialists, increased in states that implemented damage caps in the third wave of reform versus states that did not. Additionally, younger physicians may make decisions about where to establish careers and what types of residencies to enter and older physicians may make decisions about whether or not to retire. One study using data from 1993–2001 found only weak evidence that some physicians on the margins of their careers make entry and exit decisions in part based on the size and number of malpractice payments.26 Our paper provides an opportunity to reevaluate if physicians on the margins of their careers are responsive to malpractice environments.

Our paper makes several useful innovations to prior studies evaluating this question. First, we explore how physicians across different ages respond to caps on non-economic damages. Second, by using a reverse natural experiment that uses only states with non-economic damage caps at some point during the study period, we avoid the problem of using as a control group states without non-economic damage caps that may actually lose physicians if physicians relocate from these states to states newly enacting non-economic damage caps. If the control group loses physicians due to malpractice reform in other states, this could cause traditional DD estimates to be too large because of “double-counting.” Third, similar to Paik, Black, and Hyman23 we use an event study to evaluate the year-over-year change in the supply of physician labor, both in the years leading up to and after the enactment of non-economic damage caps. This allows us to observe any heterogeneity in effects of the policy in either the pre-period or the post-period. This later approach was also used by.

Data

For state malpractice law information, we used the Database of State Tort Law Reforms Version 5 (DSTLR5), which is the most comprehensive dataset of state-level malpractice reforms.21 This dataset contains a description of each reform, the year of the reform, and other details about the reform (e.g., whether the reform was held up by the states’ court). If a reform was passed in the first half of the year, the DSTLR5 lists that year as the year of the reform (e.g. reform passed in first half of 2005 and listed as 2005 in DSTLR5). If a reform was passed in the second half of the year, the DSTLR5 lists the next year as the year of the reform (e.g. reform passed in second half of 2005 is listed as 2006 in DSTLR5). Our primary variable of interest is malpractice caps on non-economic damages; however, we also control for caps on punitive damages, caps on total damages, split recovery reform, collateral source reform, punitive evidence reform, periodic payments (none, discretionary, mandatory), contingency fee, joint and several liability reform, and patient compensation fund reform. Eleven states implemented non-economic damage caps during our study period, hence we evaluate the effect of this policy change versus enacting caps on punitive damages (3 states) or total damages (no changes).

For physician supply, we used data from the Area Health Resources File (AHRF), which is a county-level database maintained by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Resources and Services Administration.27 The AHRF contains data on health resources including physician supply, which includes residents and fellows, by specialty and age. We followed the literature to group active non-federal physicians into high-malpractice risk and low-malpractice risk specialty types based on claims awarded if this data was available,10,22 or based on claims filed if not.10 High-risk specialties are defined as neurological surgery, plastic surgery, thoracic surgery, anesthesiology, emergency medicine, radiology, cardiovascular disease, gastroenterology, pulmonary disease, orthopedic surgery, urology, neurology, general surgery, OBGYN, general practice, and general internal medicine. Low-risk specialties are defined as psychiatry, physical med rehab, public health, allergy immunology, dermatology, family medicine, pediatrics, ophthalmology, diagnostic radiology, and pathology. Additionally, we further grouped these high-risk and low-risk non-federal active physicians into age categories (<35 years of age, 35–54 years of age, ≥55 years of age) to explore if damage caps have differential effects on physicians of different ages; for example, by having disproportionate effects on relocation or early retirement decisions.

For non-malpractice-related state-level characteristics that vary over time, we used median household income information from the AHRF file (inflation-adjusted to 2011 dollars), and we used the percentage of the population in different age-gender cohorts from Census data that was adjusted by the Survey of Epidemiology and End Results (SEER).28 We used the SEER data to create 18 age categories of 0–4, 5–9, 10–14, […], 80–84, 85+) for both men and women, creating 36 variables in total.

In our analysis, we use data from 2000 to 2011, which allows at least three years to elapse before a damage cap was newly implemented during the years of 2003 to 2006. Physician supply data was not provided by the AHRF data for year 2009, and so we exclude this year from our analysis. We exclude three states—Wisconsin, Georgia, and Illinois--from all analyses because Wisconsin repealed its damage cap during the study period, and Georgia and Illinois both implemented damage caps and had them quickly repealed by the courts during the study period.

Empirical Methods

We estimate the following model using a panel of the counts of physicians operating in a given state for each year across 2000–2011:

Our main outcome variable is the number of active non-federal high-risk and low-risk physicians in each state per 100,000 residents (hereafter referred to as people), by age (<35 years of age, 35–54 years of age, ≥55 years of age). The same categorization of age was used in another paper to identify physicians at the margins of their careers.26 A secondary outcome is the supply of six common (>1 specialist per 100,00 people) high-risk physician specialty types: anesthesiology, emergency medicine, orthopedic surgery, general surgery, OBGYN, and general internal medicine.

Our objective is to measure the impact of enacting non-economic damage caps on physician supply. To accomplish this, we attempt to remove sources of omitted variable bias by controlling on the right-hand side for variables that may be correlated with differential propensities to enact malpractice laws and, separately, variables that are correlated with physician supply (Xst). Age-gender cohorts and income levels of the population may correlate with physician supply by increasing demand for certain types of specialist care, and may also correlate with political pressure to enact malpractice reform. Therefore, we control for these population-level variables. Following Helland and Seabury,22 we also control for other types of malpractice law policies as a proxy for political pressure to enact non-economic damage caps. These other policies are shown in Table 1 and are punitive damages, split recovery reform, collateral source reform, punitive evidence reform, periodic payments (none, discretionary, mandatory), contingency fee, joint and several liability reform, and patient compensation fund reform.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics for States with Malpractice Caps on Non-Economic Damages, 2000–2011

| Variable | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 209 | 2005.182 | 3.441 | 2000 | 2011 |

| High-Risk Physicians, <35 Years of Age | 209 | 14.138 | 6.630 | 3.007 | 35.165 |

| High-Risk Physicians, 35–54 Years of Age | 209 | 57.320 | 11.259 | 35.358 | 94.554 |

| High-Risk Physicians, ≥55 Years of Age | 209 | 34.203 | 9.039 | 20.242 | 64.288 |

| Low-Risk Physicians, <35 Years of Age | 209 | 11.236 | 3.175 | 4.265 | 17.434 |

| Low-Risk Physicians, 35–54 Years of Age | 209 | 43.215 | 8.054 | 28.461 | 61.677 |

| Low-Risk Physicians, ≥55 Years of Age | 209 | 23.577 | 6.200 | 14.569 | 42.948 |

| Median Annual Income Per Household (in 1000s of 2011 dollars) | 209 | 51.759 | 8.819 | 36.963 | 73.970 |

| Caps Non-Economic Damages | 209 | 0.828 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Caps Punitive Damages | 209 | 0.373 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Caps Total Damages | 209 | 0.053 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Split Recovery Reform | 209 | 0.158 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Collateral Source Reform | 209 | 0.651 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Punitive Evidence Reform | 209 | 0.947 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Periodic Payments - None | 209 | 0.335 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Periodic Payments Reform Discretionary | 209 | 0.201 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Periodic Payments Reform Mandatory | 209 | 0.464 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Contingency Fee Reform | 209 | 0.292 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Joint and Several Liability Reform | 209 | 0.904 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Patient Compensation Fund Reform | 209 | 0.244 | - | 0 | 1 |

Notes: Our analysis includes 19 states with malpractice caps either during the whole period of 2000–2011, or with new malpractice caps during this period. We exclude three states—Wisconsin, Georgia, and Illinois-- because Wisconsin repealed its damage cap during the study period, and Georgia and Illinois both implemented and repealed a damage cap during the study period. 36 age-gender cohorts are not shown in this table, but are controlled for in the regression analysis.

We also control for year and state fixed effects (γs, γt) to remove unobservable variation within states and years. There were no new caps on total damages during our study period, hence our inclusion of state fixed effects controls for this time-invariant policy.

Our main predictor variables are state malpractice caps on non-economic damages between 2000 and 2011. We use an event study design to observe heterogeneity in the effects of the policy in the post-period, and to test for evidence of the parallel trends assumption being met in the pre-period. The event study permits us to detect year-over-year differences in the supply of physicians in the years leading up to and after the implementation of non-economic damage caps. Our event study is represented in our equation by indicator variables that turn on and stay on at different temporal distances before or after the enactment of non-economic damage caps. The interpretation for these coefficients is the difference in physician supply compared to the prior period (e.g. caps,t+2 is the difference in physician supply two years before a cap versus three years before). We calculate a Wald test of significance for the three policy leads to determine if there is any evidence of the parallel trends assumption (i.e. H0: caps,t+3 + caps,t+2 + caps,t+1 = 0). We also estimate linear combinations of the coefficients in the year of the law change and in each subsequent period after to determine the cumulative effect of the law change.

We originally performed a difference-in-difference analysis on the 47 states that did not rescind non-economic damage caps during our study period of 2000–2011, but our identification strategy was confounded by non-parallel trends in the pre-period, as noted by Helland and Seabury.22 Non-parallel time trends may suggest the presence of an omitted time varying variable correlated with both the enactment of malpractice caps and labor supply, thus biasing our association. It may also suggest policy endogeneity. Failure to correct for this will lead to a biased estimate of the effect of non-economic damage caps.

We explore using alterative control groups of states that either did not adopt non-economic damage caps at any point in our study, or states that adopted in year 2000 or earlier. We compared the coefficients on the policy leads using these two control groups, and we determined that using states that had adopted in year 2000 or earlier exhibited the least evidence of policy endogeneity. Therefore, for our main results we perform a reverse natural experiment,29 by performing our analysis on 19 states with non-economic damage caps at some point in the study period. We compare physician supply in 9 states that newly enacted non-economic damage caps to physician supply in 10 states that had non-economic damage caps in place for the full duration of the study. The 19 states that we use in this reverse natural experiment are identified, along with the year that the non-economic damage cap was implemented, in Table 2. This natural experiment approach also has the advantage of using a control group that is unlikely to be impacted by a decrease in physician supply if physicians indeed do relocate from states without non-economic damage caps to states newly enacting these caps, which could spuriously inflate DD estimates by “double-counting” the same physician (once when they leave the control state and again when they arrive in the treatment state).

Table 2.

Caps on Non-Economic Damages by State

| State | Years Cap Implemented |

Statute |

|---|---|---|

| States with new caps (2000–2011) | ||

| Alaska | 2006 | AK ST §09.55.549 |

| Florida | 2003 | West’s F.S.A. § 766.118 |

| Idaho | 2004 | ID ST § 6-1603 |

| Mississippi | 2003 | Miss. Code Ann. § 11-1-60 |

| Nevada | 2003 | NV ST 41A.035 |

| Oklahoma | 2004 | 63 Okl.St.Ann § 1-1708.1F |

| South Carolina | 2006 | SC ST § 15-32-220 |

| Texas | 2004 | Tex. Civ. Prac. And Rem. 74.301 |

| West Virginia | 2003 | W. Va. Code § 55-7B-8 |

| States with existing caps (2000–2011) | ||

| California | 1975 | CA CIVIL s 3333.2 |

| Colorado | 1987 | CO ST S 13-64-302 |

| Hawaii | 1987 | HI ST § 663-8.7 |

| Kansas | 1987 | KS ST § 60-19a02 |

| Maryland | 1987 | MD CTS & JUD PRO § 3-2A-09 |

| Missouri | 1986 | Mo. Stat. § 538.210 |

| Montana | 1996 | MT ST 25-9-411 |

| North Dakota | 1996 | ND ST 32-42-02 |

| South Dakota | 1996 | SD ST § 21-3-11 |

| Utah | 1988 | U.C.A. 1953 § 78B-3-410 |

Notes: Wisconsin, Georgia, and Illinois are excluded from this analysis because Wisconsin repealed its damage cap during the study period, and Georgia and Illinois both implemented damage caps and had them quickly repealed by the courts during the study period.

Our equation was estimated using a fixed effects ordinary least squares regression model. Standard errors were clustered at the state level, and each state-level observation was weighted by its population.

Results

Descriptive statistics for our sample of 19 states with malpractice caps at some point during the period of 2000–2011 are provided in Table 1, with 209 observations at the state-year level. The average state had 14.1 high-risk physicians <35 years of age per 100,000 people, 57.3 high-risk physicians 35–54 years of age per 100,000 people, and 34.2 high-risk physicians ≥55 years of age per 100,000 people. The number of low-risk physicians was smaller for each physician age cohort. The median average annual income per household was $51,759. Not displayed in the descriptive statistics table, but controlled for in the regression analysis, is 36 age-gender cohort variables for each state. Our sample of 19 states had a non-economic damage cap in place 82.8% of the time, which is higher than the national average due to dropping states without non-economic damage caps.

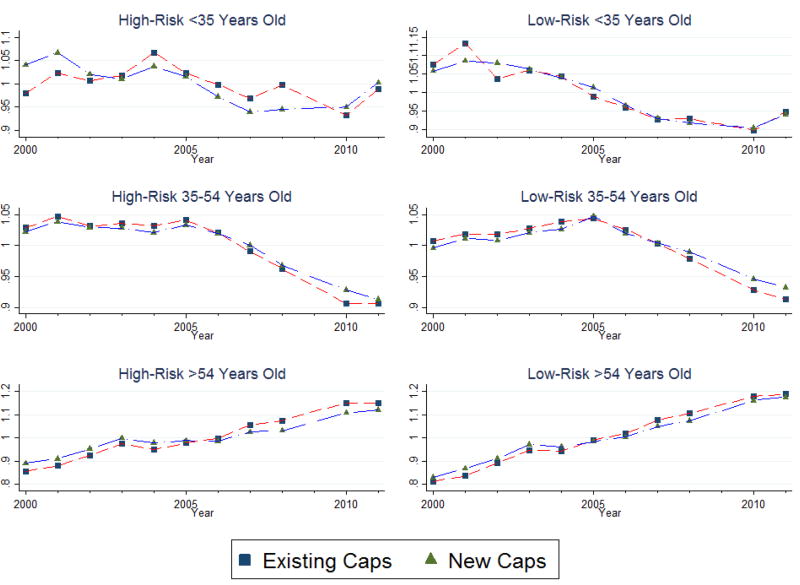

In Figure 1, we first explore the trends in physician labor (represented as differences from the mean), separately for states enacting new caps between 2003–2006 and for states with caps enacted prior to 2000, and separately by physician-risk categories. The levels of physician supply are higher for states with existing caps. We might expect to see shifts in physician supply in the 2003–2006 period during which malpractice caps were being enacted, or shortly after, but we do not see any obvious visual evidence of this. However, the graphical evidence does not control for heterogeneity by group in other malpractice policies or state-level demographics (income and age), which we can control for using regression analysis. In Online Figure 1, we show the same figure for states enacting new caps between 2003–2006 and for states not enacting caps during our study period. While the trends between all three groups appear fairly similar, we show upcoming that the coefficients on the policy leads demonstrated less evidence of policy endogeneity when the control group was states with existing caps rather than without caps.

Figure 1.

Differences from the Mean in Physician Supply per 100,000 people in States with Existing Caps on Non-Economic Damages and States with New Caps on Non-Economic Damages

Notes: Physicians include all active, non-federal physicians. New caps were enacted between 2003 and 2006.

Table 3 presents an event study of the effect of non-economic damage caps on the number of active non-federal physicians per 100,000 people, separately by risk and age. This model controls for state characteristics (e.g. 36 age-gender cohorts, median household income, and other malpractice policies), year fixed effects, and state fixed effects. The coefficients can be interpreted as the change in physician labor from the prior period.

Table 3.

Trends in Physician Supply per 100,000 people in States with Malpractice Caps on Non-Economic Damages Before and After Implementation, by Physician Risk Type and Age

| Number of Years Before or After Damage Cap |

High-Risk, <35 Years of Age |

High-Risk, 35–54 Years of Age |

High-Risk, ≥55 Years of Age |

Low-Risk, <35 Years of Age |

Low-Risk, 35–54 Years of Age |

Low-Risk, ≥55 Years of Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Years Before | 0.13 [0.51] | −0.68 [0.45] | 0.23 [0.37] | −0.03 [0.20] | 0.59* [0.24] | 0.13 [0.32] |

| 2 Years Before | −0.2 [0.21] | 0.18 [0.25] | −0.13 [0.31] | 0.1 [0.18] | 0.04 [0.18] | −0.02 [0.25] |

| 1 Year Before | −0.19 [0.20] | −0.36 [0.30] | −0.07 [0.29] | 0.24 [0.20] | 0.07 [0.26] | −0.33 [0.20] |

| Year of Non-Economic Damage Cap | −0.36 [0.35] | 0.17 [0.71] | 0 [0.47] | 0.61 [0.34] | 0.78 [0.58] | −0.75 [0.43] |

| 1 Year After | 0.93** [0.24] | 0.37 [0.38] | −0.38 [0.32] | 0.05 [0.13] | −0.04 [0.23] | 0.04 [0.19] |

| 2 Years After | 0.26 [0.19] | −0.43 [0.33] | −0.25 [0.16] | −0.28** [0.09] | −0.14 [0.25] | 0.17 [0.23] |

| 3 Years After | 0.54*** [0.11] | 0.22 [0.28] | −0.57* [0.26] | 0.11 [0.17] | 0.44 [0.24] | −0.19 [0.19] |

| 4 Years After and Beyond | 0.69** [0.21] | 0.56 [0.34] | −0.05 [0.31] | −0.28 [0.16] | 0.15 [0.23] | 0.48* [0.22] |

| p-value for Pre-Trend | 0.281 | 0.135 | 0.855 | 0.562 | 0.147 | 0.16 |

| Linear Combination of Post-Cap Coefficients | 2.055*** [0.44] | 0.884 [0.604] | −1.255 [0.871] | 0.216 [0.294] | 1.184* [0.502] | −0.26 [0.419] |

| Sample | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 |

| Mean | 16.532 | 59.549 | 37.833 | 11.645 | 40.978 | 25.15 |

| State Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: State characteristics include annual income, 36 age-gender cohorts, and all of the additional malpractice reform variables included in Table 1.

Significant at the 0.1 percent level.

Significant at the 1 percent level.

Significant at the 5 percent level.

Among the 19 states that we use in our reverse natural experiment, the time trends appear to be parallel, as represented by only one statistically significant coefficient in the three years before non-economic damage caps for our six outcome variables. Further, we conducted a joint Wald test to determine the overall significance of changes in physician supply in the three years before non-economic damage caps were enacted, and the reported p-values were not statistically significant. Overall, this suggests that we do not observe evidence of states endogenously implementing damage caps in response to declining physician supply.

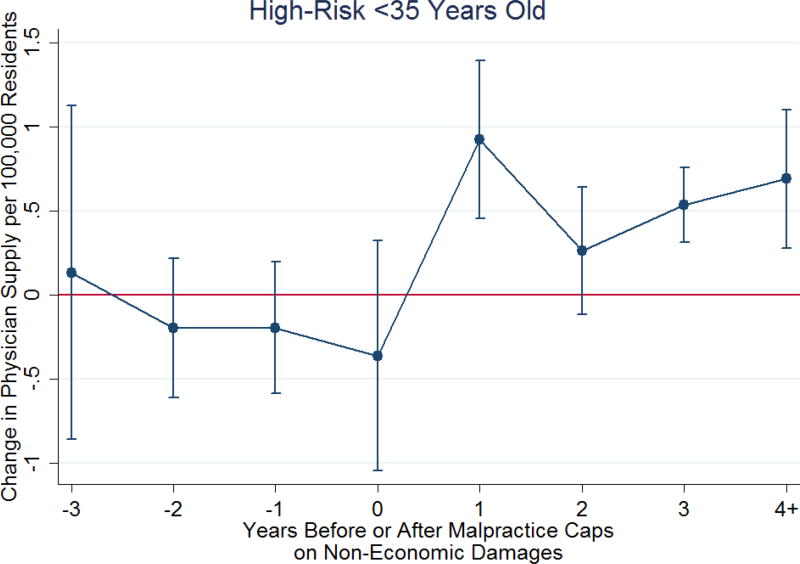

Among high-risk physicians <35 years of age, we observe a statistically significant increase in physician supply of 0.93 physicians per 100,000 people in the first year after non-economic damage caps were enacted (p<0.01), a statistically significant increase in physician supply of 0.54 physicians per 100,000 people three years after non-economic damage caps were enacted (p<0.001), and a statistically significant increase in physician supply of 0.64 physicians per 100,000 people in the fourth year and beyond after non-economic damage caps were enacted (p<0.01). These findings for high-risk physicians <35 years of age are also shown in Figure 2. The cumulative effect of enacting non-economic damage caps was to increase the supply of high-risk physicians <35 years of age by 2.1 physicians per 100,000 people (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Year-Over-Year Change in Physician Supply of High-Risk Physicians <35 Years Old

Notes: This provides a visual representation of the results shown in the second column of Table 3. Confidence intervals are at the 95% level

We do not see any consistent evidence of a change in the supply of high-risk physicians between the ages of 35–54 or ≥55 years of age. For the oldest physicians, malpractice caps were associated with a reduction in physician supply of −0.6 physicians per 100,000 people (p<0.05) in the third year after non-economic damage caps were enacted, which is opposite of our prediction. However, the lack of any cumulative effect in physician supply for middle-age and older high-risk physicians leads us to speculate that this reduction in physician supply is not meaningfully associated with non-economic damage caps. Indeed, 1 in 20 coefficients will be statistically significant by random chance at p<0.05. We conclude that there is strong evidence of the enactment of non-economic damage caps cumulatively increasing the supply of high-risk physicians <35 years of age, and no consistent evidence of the caps having an impact on the supply of older high-risk physicians.

Among low-risk physicians, the coefficients are generally small in magnitude compared to the coefficients in the post period for high-risk physicians <35 years of age. We see one statistically significant decline in physician supply of 0.28 physicians <35 years of age per 100,000 people in the second year after non-economic damage caps were implemented (p<0.01). This suggests that some of the increase in physician supply may have been offset by lower supply of young low-risk physicians. An increase in physician supply of 0.5 physicians per 100,000 people is shown 4 years and after for low-risk physicians ≥55 years of age (p<0.05), but this again does not appear to be meaningfully associated with non-economic damage caps. Collectively, there is little evidence that the supply of low-risk physicians was affected by the enactment of non-economic damage caps.

In contrast, in Online Table 1, we use states not adopting non-economic damage caps as our control group for adopting states. In this case, the coefficient on the policy lead one year before adoption is statistically significant and large for middle-aged physicians. This suggests that using previously-adopting states as our control group is a more suitable comparison group. However, our finding of a large increase in physician supply in the year after adoption for high-risk physicians <35 years of age was consistent regardless of the control group used.

In Table 4 we replicate Table 3 for 5 states enacting non-economic damage caps of $250,000 or less (AK, ID, TX, UT, WV) compared to 3 states with these strong caps throughout the full study period (CA, KS, MT). Our estimates are less precise since we are only using eight states, but we find some evidence that cumulative effects of the policy are larger. The supply of high-risk physicians <35 years of age is estimated to have increased by 3.4 physicians per 100,000 in these states adopting strong caps on non-economic damages (compared to 2.1 physicians per 100,000 in all states adopting non-economic damage caps). We also find evidence from this table of a possible large increase in physician supply from middle-aged high-risk physicians (13.5 physicians per 100,000, p<0.01). In a surprising finding, low-risk, older physicians in states adopting strong caps on non-economic damages may have also increased their labor, which was opposite in sign from our earlier results in Table 2.

Table 4.

Trends in Physician Supply per 100,000 people in States with Strong Malpractice Caps on Non-Economic Damages (≤$250,000) Before and After Implementation, by Physician Risk Type and Age

| Number of Years Before or After Damage Cap |

High-Risk, <35 Years of Age |

High-Risk, 35–54 Years of Age |

High-Risk, ≥55 Years of Age |

Low-Risk, <35 Years of Age |

Low-Risk, 35–54 Years of Age |

Low-Risk, ≥55 Years of Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Years Before | −0.11 [0.83] | 0.22 [0.77] | 1.17 [0.74] | −0.02 [0.51] | 1.11 [0.47] | 0.46 [0.41] |

| 2 Years Before | −0.03 [0.28] | 0.61 [0.82] | 0.28 [0.51] | 0.37 [0.42] | −0.38 [0.39] | 0.4 [0.20] |

| 1 Year Before | −0.9 [0.64] | 0.1 [0.63] | 0.08 [0.55] | 0.01 [0.49] | −0.37 [0.52] | 0.09 [0.15] |

| Year of Non-Economic Damage Cap | 1.05 [2.69] | 7.10* [2.95] | −1.1 [1.47] | 2.23 [1.08] | −1.9 [2.07] | 3.1 [1.33] |

| 1 Year After | 0.03 [0.81] | 2.07* [0.83] | 0.46 [0.86] | 0.71 [0.82] | −0.92 [0.61] | 1.24* [0.38] |

| 2 Years After | 0.52 [1.00] | 0.73 [0.52] | 0.22 [0.45] | 0.15 [0.78] | −0.52 [0.62] | 0.82** [0.19] |

| 3 Years After | 0.31 [0.68] | 1.46 [0.63] | −0.81 [0.70] | 0.65 [0.47] | −0.26 [0.32] | 0.25 [0.43] |

| 4 Years After and Beyond | 1.48 [0.72] | 2.18* [0.78] | −0.09 [0.35] | 0.08 [1.09] | −0.59 [0.45] | 1.02* [0.39] |

| p-value for Pre-Trend | 0.364 | 0.678 | 0.15 | 0.718 | 0.001 | 0.263 |

| Linear Combination of Post-Cap Coefficients | 3.394 [5.229] | 13.549** [3.535] | −1.315 [2.777] | 3.826 [3.496] | −4.187 [3.12] | 6.434* [2.185] |

| Sample | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 |

| Mean | 16.565 | 56.387 | 37.777 | 11.849 | 40.513 | 25.621 |

| State Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: State characteristics include annual income, 36 age-gender cohorts, and all of the additional malpractice reform variables included in Table 1.

Significant at the 0.1 percent level.

Significant at the 1 percent level.

Significant at the 5 percent level.

Finally, in Table 5, we explore heterogeneity in the adoption of non-economic damage caps for young physicians across different high-risk physician specialist groups (>1 specialist per 100,000 people). Emergency medicine and general internal medicine specialists exhibit the most consistent evidence of responding to non-economic damage caps. The supply of emergency medicine specialists increased by 0.24 physicians per 100,000 people (p<0.001) in the year following the adoption of non-economic damage caps, which was an increase of 15% of the mean. Non-economic damage caps were also associated with higher numbers of general internal medicine specialists in the year of passage and in each subsequent year. The cumulative increase in emergency medicine physicians was 0.48 / 100,000 people (p<0.001) and the cumulative increase in general internal medicine physicians was 1.17 / 100,000 people (p<0.001).

Table 5.

Trends in Physician Supply per 100,000 people in States with Malpractice Caps on Non-Economic Damages Before and After Implementation, by Physician High-Risk Physician Specialty Type, <35 Years of Age

| Number of Years Before or After Damage Cap |

Anesthesiology | Emergency Medicine |

Orthopedic Surgery |

General Surgery |

OBGYN | General Internal Medicine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Years Before | 0.06 [0.07] | −0.07 [0.07] | 0.05 [0.08] | −0.16 [0.11] | −0.08 [0.07] | 0.25 [0.37] |

| 2 Years Before | 0.03 [0.04] | −0.04 [0.04] | −0.05 [0.05] | 0.04 [0.10] | 0.06 [0.04] | −0.21 [0.15] |

| 1 Year Before | −0.05 [0.06] | −0.02 [0.05] | −0.05 [0.04] | 0.08 [0.06] | 0 [0.04] | −0.05 [0.10] |

| Year of Non-Economic Damage Cap | −0.30* [0.11] | −0.01 [0.08] | 0.03 [0.06] | −0.12 [0.11] | −0.12 [0.07] | 0.12 [0.17] |

| 1 Year After | 0.02 [0.06] | 0.24*** [0.05] | −0.03 [0.06] | 0.23* [0.09] | 0.11 [0.07] | 0.36*** [0.08] |

| 2 Years After | 0.05 [0.04] | 0.02 [0.06] | −0.01 [0.05] | 0.03 [0.05] | 0.02 [0.05] | 0.2 [0.17] |

| 3 Years After | 0.01 [0.04] | 0.08 [0.05] | 0.03 [0.04] | 0.04 [0.09] | 0.12* [0.05] | 0.27* [0.10] |

| 4 Years After and Beyond | 0.08 [0.06] | 0.16* [0.07] | 0 [0.04] | 0.14* [0.06] | 0.05 [0.05] | 0.22 [0.11] |

| p-value for Pre-Trend | 0.72 | 0.503 | 0.463 | 0.011 | 0.443 | 0.428 |

| Linear Combination of Post-Cap Coefficients | −0.145 [0.105] | 0.48*** [0.139] | 0.024 [0.073] | 0.321 [0.168] | 0.173 [0.117] | 1.172*** [0.285] |

| Sample | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 |

| Mean | 1.484 | 1.6 | 1.008 | 2.024 | 1.794 | 6.166 |

| State Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: We show physician supply for the most common types of high-risk physician specialists <35 years of age. State characteristics include annual income, 36 age-gender cohorts, and all of the additional malpractice reform variables included in Table 1.

Significant at the 0.1 percent level.

Significant at the 1 percent level.

Significant at the 5 percent level

Discussion

In this study, we perform a reverse natural experiment among 19 states that either had non-economic damage caps in place during the full study period, or that enacted them during the third wave of malpractice reforms between 2003 to 2006. We find evidence that the supply of high-risk physician specialists <35 years of age rose due to the enactment of non-economic damage caps. This provides evidence of an effect of malpractice caps on non-economic damages for physicians at the entry point of their careers. Our event study design provides evidence of both immediate and delayed impacts of enacting non-economic damage caps on the supply of young, high-risk physician labor. We also find suggestive evidence of greater physician supply responsiveness to strong caps of $250,000 or less. These increases in response to strong caps were not limited to strictly young, high-risk physicians. Finally, we find evidence of particularly strong responsiveness to caps on non-economic damages by young emergency medicine physicians and general internal medicine physicians.

Our results are similar in spirit to those of Helland and Seabury,22 who used a DDD model to identify an increase in physician supply of high-risk physicians relative to low-risk physicians in states adopting malpractice caps versus states that did not. A benefit of our study is that we can estimate causal effects for both low- and high-risk physicians; whereas Helland and Seabury could only estimate the differential effect between the two groups. Differentials are less valuable to policymakers than direct evidence of the likely effects of non-economic damages caps on certain types of physicians, such as young family practice physicians.

Paik, Black, and Hyman23 argue that non-economic damage caps did not increase the supply of physician labor. We find evidence that they did—but primarily only for young, high-risk physicians. Our results suggest the importance of considering age of the physicians in future studies in non-economic damage caps.

We also argue that states without non-economic damage caps are potentially a poor control unit because of the possibility that physicians will relocate from these states without non-economic damage caps to states newly adopting non-economic damage caps. We solve this problem by using a reverse natural experiment that keeps only states with non-economic damage caps at some point in the study period.

In conclusion, our study finds that implementing non-economic damage caps may be a successful way for states to increase their supply of young, high-risk physicians, but is likely ineffective in increasing the supply of low-risk physicians like primary care physicians.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Non-economic damage caps increased the supply of high-risk physicians <35 years of age.

Stronger non-economic damage caps generally had a larger impact on physical supply.

Emergency medicine and general internal medicine specialists were particularly responsive.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Bishop is supported by a National Institute on Aging Career Development Award (K23AG043499) and by funds provided as Nanette Laitman Clinical Scholar in Public Health at Weill Cornell Medical College. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclaimers: None

References

- 1.Kirch DG, Henderson MK, Dill MJ. Physician workforce projections in an era of health care reform. Annu. Rev Med. 2012;63:435–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050310-134634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitka M. Looming shortage of physicians raises concerns about access to care. JAMA. 2007;297(10):1045–1046. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Physicians. Creating a new national workforce for internal medicine. 2006 http://www.acponline.org/advocacy/current_policy_papers/assets/im_workforce.pdf.

- 4.Freed GL, Nahra TA, Wheeler JR. Counting physicians: Inconsistencies in a commonly used source for workforce analysis. Acad. Med. 2006;81(9):847–852. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200609000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Comparison of physician workforce estimates and supply projections. JAMA. 2009;302(15):1674–1680. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an aging America: building the healthcare workforce. [Accessed October 27, 2014];2008 Available at http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2008/Retooling-for-an-Aging-America-Building-the-Health-Care-Workforce/ReportBriefRetoolingforanAgingAmericaBuildingtheHealthCareWorkforce.pdf.

- 7.Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician Shortages to Worsen Without Increases in Residency Training. [Accessed October 27, 2014]; Available at https://www.aamc.org/download/153160/data/physician_shortages_to_worsen_without_increases_in_residency_tr.pdf.

- 8.American Medical Association. Medical Liability Reform--NOW! Chicago, IL: Feb 5, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dranove D, Gron A. Effects of the malpractice crisis on access to and incidence of high-risk procedures: Evidence from Florida. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(3):802–810. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.3.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice Risk According to Physician Specialty. New Engl J. Med. 2011;365(7):629–636. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1012370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Brennan TA. Medical malpractice. N Engl J. Med. 2004;350(3):283–292. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr035470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bishop TF, Klotman PE, Vladeck BC, Callahan MA. The future of malpractice reform. Am J. Med. 2010;123(8):673–674. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Congressional Budget Office. Letter to Senator Orrin Hatch. [Accessed May 14, 2016];2009 http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/106xx/doc10641/10-09-tort_reform.pdf.

- 14.Zuckerman S, Bovbjerg RR, Sloan F. Effects of tort reforms and other factors on medical malpractice insurance premiums. Inquiry. 1990;27(2):167–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sloan FA. State responses to the malpractice insurance "crisis" of the 1970s: an empirical assessment. J Health Polit Policy. Law. 1985;9(4):629–646. doi: 10.1215/03616878-9-4-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rock SM. Malpractice premiums and primary cesarean section rates in New York and Illinois. Public Health. Rep. 1988;103(5):459–463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Congressional Budget Office. Letter to Senator Orrin Hatch. [Accessed July 1, 2012];2009 Oct 9; Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/106xx/doc10641/10-09-tort_reform.pdf.

- 18.Anderson RE. Billions for defense: the pervasive nature of defensive medicine. Arch Intern. Med. 1999;159(20):2399–2402. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.20.2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessler D, McClellan M. Do doctors practice defensive medicine. Q J Econ. 1996(111):353–390. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. Physicians' views on defensive medicine: a national survey. Arch Intern. Med. 2010;170(12):1081–1083. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avraham R. DSTLR 5th 1980–2012. 2015 https://law.utexas.edu/faculty/ravraham/dstlr.php.

- 22.Helland E, Seabury SA. Tort reform and physician labor supply: A review of the evidence. Int Rev Law Econ. 2015;42:192–202. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paik M, Black B, Hyman DA. Damage Caps and the Labor Supply of Physicians: Evidence from the Third Reform Wave. American Law and Economics Review. 2016;18(2):463–505. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Encinosa WE, Hellinger FJ. Have state caps on malpractice awards increased the supply of physicians? Health Aff (Millwood) 2005 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.250. Suppl Web Exclusives:W5-250-W255-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler DP, Sage WM, Becker DJ. Impact of Malpractice Reforms on the Supply of Physician Services. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2618–2625. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katherine Baicker, Chandra A. NBER Working Paper Series. Cambridge: NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH; 2004. The Effect of Malpractice Liability on the Delivery of Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health Resources and Services Administration. Area Health Resources Files (AHRF) Overview. [Accessed October 27, 2014]; Available at http://ahrf.hrsa.gov/overview.htm.

- 28.The National Bureau of Economic Research. Survey of Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) U.S. State and County Population Data. 2016 http://www.nber.org/data/seer_u.s._county_population_data.html.

- 29.Gruber J. The Incidence of Mandated Maternity Benefits. Am Econ. Rev. 1994;84(3):622–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.