Abstract

One of the ongoing challenges for academic, biotech and pharma organizations involved in oncology-related research and development is how to help scientists be more effective in transforming new scientific ideas into products that improve patients’ lives. Decreasing the time required between bench work and translational study would allow potential benefits of innovation to reach patients more quickly. In this study, the time required to translate cancer-related biomedical research into clinical practice is examined for the most common cancer cases including breast, lung and prostate cancer. The calculated “time lag” typically of 10 years for new oncology treatments in these areas can create fatal delays in a patient’s life. Reasons for the long “time lag” in cancer drug development were examined in detail, and key opinion leaders were interviewed, to formulate suggestions for helping new drugs reach from bench to bed side more quickly.

Keywords: Time lag, cancer, translational study, technology transfer

Introduction

Basic biomedical research requires huge amount of financial investment. In 2017, the federal budget will provide $14.6 billion for basic research, $1 billion as an initiative for cancer research, and $33.1 billion for biomedical research (1). However, transforming this investment into an innovation to improve public health takes tremendous amount of time, which causes delays of potential patient benefit.

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in United States. According to the latest statistics, 595,690 American are predicted to die from cancer by the end of 2016, which equals to 1,600 deaths per day (2). Breast cancer will be the most common cancer in women with 246,660 new cases predicted, prostate cancer will be the most common cancer in men with 180,890 new cases predicted, and lung cancer will be the second most common in both women and men with 117,920 new cases predicted in 2016.

On one side of the coin, one might well say that cancer patients race with time for their lives. On the other side of the coin however, despite the tremendous amounts of time and money invested in biomedical research, the translation of basic biological discoveries into clinical applications takes a frustratingly long time. Therefore the “time lag” between basic biomedical research and translation of the resulting innovations into public health improvements deserves more attention (3).

In this study, firstly, the length of time between patent application and approval of a new cancer drug is examined. For this purpose, the three most common cancer types - breast, prostate and lung cancer - were chosen. As part of this study it is clearly important to understand the pace of current basic biomedical research and to develop potential solutions to the obstacles and challenges that it faces. With this in mind, in the second part of the study the reasons for this “time lag” in biomedical research are studied and defined in more detail.

Methods

In the first part of the study, information from the Pharmaprojects® database (produced by Citeline/Informa PLC) was used to calculate time lags of breast, lung and prostate cancer drugs. The time length between patent priority date, date of regulatory filing of the initial application and approval date of the new drug was calculated for each drug, and the average time length was calculated. Patent priority date of a new drug is considered as a publication date, and most of the drugs have patent protection. However, some of the Pharmaprojects® drug profiles did not include patent information, and in those cases the date of the first press release or publication was considered to be the publication date. Drugs without patent, publication or approval dates were eliminated.

In the second part of the study, key opinion leaders were interviewed, including principal investigators, scientists, researchers from National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), Yale University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Queen’s University School of Medicine, Dentistry and Biomedical Science, Belfast (U.K), and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. The interviews were performed to better understand the reasons for the lengthy time required for drug discovery or/and the failure of basic biomedical research to reach translational study. Additional background was obtained from relevant published articles and recorded seminars, as well as attendance at the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) 2016 Annual Conference and translational study-related conferences.

During these interviews, the following questions were discussed;

What determines that basic research results are not qualified to continue to translation study?

What are possible reasons for the lengthy time required to translate basic research into clinical practice?

How could we shorten the time lag in biomedical research?

Results

Time Lag in Breast, Lung and Prostate Cancer Research

The definition of translational research is not as clear as that of basic research or clinical research, and it is described as “a process that transfers basic science findings into clinical application” or “bench to bedside”. Translation of basic research findings into medical benefit requires an enormous amount of time and money (4, 5). When we empathize with a patient who has been waiting for a cure to survive, the time that is required for the translation of a drug into clinical application becomes more critical and important than ever. On the other hand, the large investment in basic and clinical biomedical research by the government creates the expectation and pressure to see public health benefits of biomedical research. Due to these obvious reasons, the first part of the study focused on the calculation of time lag in the three most common cancer types including breast, lung and prostate cancer.

In calculating these time lags, two data points were selected for each approved drug. The first data point was the patent priority date or the initial publication date; the second data point was the regulatory approval date for the drug itself. The time lag between these two data points and average time lag for each cancer type were calculated.

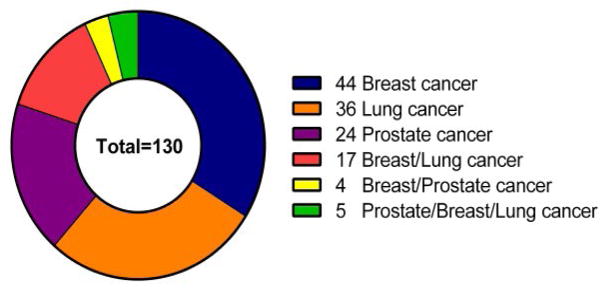

As seen in Figure 1, there are currently 44, 36, 24 approved drugs, respectively, for breast cancer, lung cancer and prostate cancer. Some of these drugs could be used for more than one cancer indication. For example, 17 drugs could be used to treat both breast and lung cancer, 4 drugs could be used to treat both breast and prostate cancer and 5 drugs could be used to treat breast, lung and prostate cancer. A total of 130 approved breast, lung, and prostate cancer drugs could potentially have been used for the calculation of time lag. However, drugs without patent priority date/publication date or launched date were excluded from the time lag calculation.

Figure 1.

The number of approved drugs for prostate, breast and lung cancer.

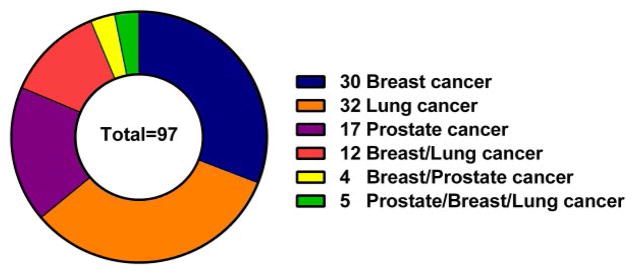

As shown in Figure 2, 97 drugs out of 130 drugs were examined for time lag calculation: 30, 32, 17 approved drugs, respectively for breast cancer, lung cancer and prostate cancer. As seen in Figure 2, 12 drugs could treat breast and lung cancer, 4 drugs could treat both breast and prostate cancer and 5 drugs could treat breast, lung and prostate cancer.

Figure 2.

The number of approved drugs that were used to calculate time lag for prostate, breast and lung cancer treatment.

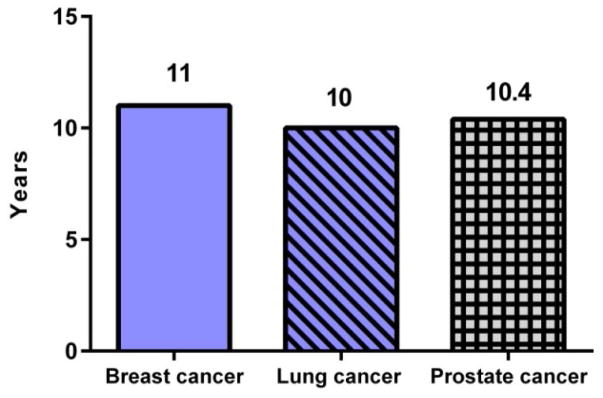

As seen in Figure 3, the average time required to launch a cancer drug was calculated to be 11 years, 10 years and 10.4 years, respectively for breast, lung and prostate cancer. In another study, the time lag for general biomedical research (not just cancer), calculated by searching publication data of 23 studies, was determined to be 17 years (6). In either instance, this is a frustratingly long time to launch a drug, cancer or otherwise. When we consider the typical conditional 5-year relative survival time for a cancer patient (7), the 10 to 11 year time required for translation of a cancer drug into clinical applications makes for a dramatically heart-breaking and fatal waiting period.

Figure 3.

Calculated “time lag” of translation of a cancer drug into clinical application for breast, lung and prostate cancer

Reasons for the Long “Time Lag” in Breast, Lung and Prostate Cancer Research

Finding the reasons for this “time lag” in new breast, lung and prostate cancer treatments is a multi-dimensional puzzle. These reasons need to be first better defined so that potential solutions can be developed by both the biotechnology industry and the research community. Clearly, the causes for this lengthy “time lag” can be divided into two categories: scientific and non-scientific.

Scientific reasons

Challenges in Reproducible Data Generation

Reproducibility is clearly one of the most important fundamental principles of science research. Reproducibility means that any laboratory could produce the same results for experiments conducted under the same conditions. Reproducible data generation is an issue in oncology research as without reproducibility, a new treatment discovery could easily be dismissed as invalid. There are multiple reasons for reproducibility problems in research studies such as weak experimental design, lack of knowledge by the investigator of basic experimental principles, inappropriate statistical analysis, inappropriate small sample size, other human error related variations, overly complex experimental procedures, and unanticipated changes (especially stability or contamination) in chemical and biological ingredients (8). The main reasons for this “time lag” in oncology related to reproducibility will now be reviewed and discussed in more detail.

Vitro-Vivo Model Differences and Mouse Models for Human Disease

Unexplored differences between in vitro (working with living cells in a dish) and in vivo (working with whole living animal) models of disease could be the source of unreproducible data generation and one biggest challenges in oncology research today. While an in vitro study could be the genesis for a novel biomedical discovery and eliminate the cost and complexity of a whole animal study, misidentified, virus or mycoplasma contaminated cells would however lead to unreliable experimental results. When such occurs it means the loss of time in general research progress and more importantly, a delay in the discovery of life-saving drugs (9). To improve reproducibility of an in vitro study, cell lines need to be periodically validated for their purity and confirmed authentication (10).

On the other hand, an in vivo study usually produces more reliable and reproducible data and early toxicology studies and potential adverse effects for a new drug should include an in vivo evaluation. One of reproducibility problems appears in case of switching from an in vitro system to an in vivo system. Often the activity of a drug compound in an in vitro system can be different than in an in vivo system due to differences between oral uptake and general absorption (11).

Human xenograft mouse models are considered as a foundation of cancer research, and they have been used for decades in drug development including safety and toxicity testing. In vivo study models are expensive and time consuming. Despite successful pre-clinical testing, mouse models often do not lead to successful practice in clinical applications due to their often overlooked historic low translational success and low reproducibility. Besides the examples for cancer, there are many mouse models for other diseases with similar low success rates. Alzheimer disease is another example for well-known but often ineffective or inefficient in vivo model systems. Approximately 36 drugs have failed in Alzheimer disease clinical trials, even though they were successful in transgenic mouse and rat models (12, 13). There are also many other reasons for low reproducibility and translational success of in vivo studies. One particularly noteworthy case is that of using healthy animals with transplanted tumors for immunological cancer treatment or drug testing. Without considering the entirety of relevant but often complex endogenous factors in cancer progression, studies that focus only on a single factor can generate in unreliable in vivo data that will not lead to subsequent successful clinical applications (14, 15, 16, and 17). Other problems are statistically poor experimental design, lack of randomization and replication as well as omitted negative results. Human patient samples, collaborations with tissue bio banks, humanized mouse models and spontaneous cancer mouse models can be considered as alternative approaches in oncology research to prevent animal model-related obstacles or delays (9).

Human Patient Samples

Even though mouse models bring advantages to ease the complexity of biomedical research, their correlation with human cancer pathology and subsequent use to measure the safety and efficiency of chemotherapeutic drugs has significant potential for failure. Taking advantage of human patient samples and tissues from bio banks should thus be in general more relevant for translational studies than mouse models. However, collection and storage of human patient samples can cause problems themselves in reproducible data generation. For example, freezing human samples could change the protein structure of the samples — later causing reproducibility problems with treatments using fresh human patient samples. Therefore, using fresh human samples could be one of the solutions to generate more reliable data.

Non-Scientific reasons

Competitor Versus Collaborator

Finding cures for a cancer has been a challenging adventure, similar in deed to a “moon shot” and collaboration thus is an inevitable requirement to shorten time lag in such biomedical research. Most of the time, failure in biomedical research can eventually be attributed to lack of fundamental understanding by one or more of participating investigators of the underlying scientific principles of the ongoing research project. Collaboration can bring a steadier pace and effectiveness into an otherwise slowly processing research program. However, the intellectual property (IP) generated from such research and resulting competition to commercialize it can be one of the obstacles to collaboration and research tool sharing in cancer research if not handled properly (18).

Intellectual Property (IP) Challenges for Sharing Research Tools

In the Unites States, the total number of the pharmaceutical and medical field related patents granted between 1964 and 2012 by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office is 168,435 (19). Both the universities and private companies that own these patents thus potentially have significant control over the biomedical research field due to this increasing amount of patent activity, including those related to research tools. However to minimize future time-lags, it is clear that drug discovery related to cancer research conducted at universities or private companies will need rapid access to state-of-the-art research tools. Unreasonable restrictions or delays in the distribution or use of such tools can stifle new discoveries, thus limiting the development of future biomedical products. In 1997, Harold Varmus, then Director of the National Institutes of Health (and later Director of the National Cancer Institute), established a Working Group to look into the increasing apprehension that intellectual property restrictions might be stifling the broad dissemination of new scientific discoveries and thus limiting future avenues of basic research, drug discovery and product development in all therapeutic areas, not only cancer. Specific areas of concern were raised in the scientific community regarding: problems or delays encountered in the distribution, licensing and use of unique research tools as well as the competing interests of intellectual property owners and research tool users. Case in point was the difficulties in cancer research being encountered due to the so-called “DuPont Oncomouse Patents” originating from Harvard University.

In response, the NIH developed guidance for NIH-funded scientists and their collaborators on tool sharing and tool distribution (whether the tool was patented or not), to facilitate the exchanges of these tools for research discoveries and product development independent of IP status. Now more than sixteen years later, these guidelines have become standard clauses for nearly all funding from government and non-profit agencies so that a proper balance has been achieved to balance the interest in accelerating scientific discovery with that also of facilitating product development for health and patient care. (18, 20).

Public-Private Partnership Challenges

Partnerships in biomedical science optimize the use of available knowledge and resources and speed the progress of biomedical research. Public-private partnerships include at a minimum at least one private and one non-profit organization working together to accelerate translation of a biomedical discovery into public health benefit. Enactment of the Bayh-Dole Act and related legislation by the U.S. Congress beginning in the 1980s marked the start of opportunities for public-private partnerships. One of the good examples for public-private partnerships is the osteoarthritis initiative partnership between the NIH and private industry. This partnership accomplishments included establishing a database of radiological images, relevant biomarkers and physical exams as objective and measurable standards for the progression of this painful and disabling disease – all of which should be helpful in reducing time lag of future biomedical research in this field (21, 22). However, despite the inherent advantages of public-private partnerships, there are still obstacles to be avoided in their use that could otherwise limit their efficient application. It will be critical, for example, to set well-articulated common goals in such a partnership for otherwise further time-lags may result that may adversely affect the outcomes of the research. Thus in a typical academia-pharmaceutical company partnership, academic scientists will likely focus on biochemical and molecular targets of the disease, while on the other hand pharmaceutical company scientists will focus on the manufacturing and clinical development of the innovative therapy. When not handled properly in advance and then managed effectively during the project, problems in public-private partnerships can result from differing end goals of each partners, unwillingness to share control and resulting financial benefits of a project, or simply differing work cultures – all of which could cause delays in translation of an innovation into a new oncology or other disease therapeutic.

Conclusions and Future Opportunities

Eroom’s law indicates that drug discovery is slower and more expensive today than the past decades. As a general trend, the number of new drugs launched per year has been decreasing, however spending in drug development process have been increasing (23). Today we have more advanced technology, more investment in biomedical research and unfortunately seemingly less positive outcomes for drug development. The trend thus appears to be more delays in drug approval, further losses in productivity of pharmaceutical research. In this study, the findings showed that the typical age of a cancer drug is at least 10 years before it ever reaches the patients. For cancer patients 10 year period translates unfortunately to more than a life time of delay. To find solution for delays and to increase productivity in oncology as well as other areas of biomedical research, the problems or roadblocks need to better articulated and understood by all participants so that corrective action can be taken. While drug discovery and clinical testing are themselves inherently difficult, there are both scientific and non-scientific reasons contributing to the time-lag in biomedical research. As described previously scientific reasons include reproducible data generation, inappropriate use of in vitro/vivo models, and variation in human sample collection. Non-scientific reasons can include are poor collaborations among interested parties, lack of sharing of research tools and weak or ineffective public-private partnership arrangements.

Future Opportunity: Establishing Stronger Academia - Industry Connection for Oncology

Besides these problems discussed above, it seems that a general disconnect exists between academia and pharmaceutical companies that also stretches the time lag between bench and bedside. This lack of connectivity between industry and universities at times may be leaving potentially brilliant ideas in the dark. Academics have deep scientific knowledge but suffer from funding problems to pursue their research and typically lack the more applied skills of later stage clinical research, regulatory and production scale-up knowledge. Pharmaceutical companies generally have funding and applied skills, but they are dependent on academics and small biotech companies for fundamental knowledge and novel discoveries. Establishing more stronger and living connections between academia and pharmaceutical companies, thus increasing clinical research knowledge of academic scientists would go far to bring better pace and synergy in biomedical research.

Future Opportunity: Repurposing of FDA Approved Drugs for Oncology Applications

During one of the interviews for this article, a principal investigator from a major university said that time lag in his research to market is only 2–3 years, because his laboratory studies FDA approved drugs for different indications. Using FDA approved drugs for other indications, which means repurposing of a drug would dramatically reduce time lag and overall cost. The more exciting part of repurposing drugs, of course, is that translation of a drug into a new treatment for a patient’s benefit will be quicker.

Acknowledgments

The work of Dr. Uygur was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Berna Uygur, Section on Membrane Biology, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892.

Josh Duberman, NIH Library, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Steven M. Ferguson, Office of Technology Transfer, National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD

References

- 1.Presidential Fiscal year 2017 budget. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rebecca L, Siegel KDM, Ahemdin J. Cancer stattistics. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins FS. Reengineering translational science: the time is right. Science translational medicine. 2011;3(90):90cm17–90cm17. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanney SR, Castle-Clarke S, Grant J, Guthrie S, Henshall C, Mestre-Ferrandiz J, et al. How long does biomedical research take? Studying the time taken between biomedical and health research and its translation into product. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2015;13(1) doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-13-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lost in translation-basic science in the era of translational research. Infection and Immunity. 2009;78(2):563–566. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01318-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational study. Journal of Royal Society of Medicine. 2011:104. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen-Heijnen ML, Houterman S, Lemmens VE, Brenner H, Steyerberg EW, Coebergh JW. Prognosis for long-term survivors of cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(8):1048–1413. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reproducibility and reliability of biomedical research: improving research practice. The Academy of Science, Symposium Report 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gawrylewski A. The scientists. 2007. Trouble with mouse models. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorsch JR, Collins FS, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Fixing problems with cell lines. Science. 2014;346(6216):1452–1453. doi: 10.1126/science.1259110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedhoff LT. New Drugs: An Insider’s Guide to the FDA’s New Drug Approval Process, for Scientists, Investors, and Patients. Pharmaceutical Special Projects Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fulmer T. Animal instincts. SciBX: Science-Business eXchange. 2012;5(44) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavanaugh SE, Pippin JJ, Barnard ND. Animal models of Alzheimer disease: historical pitfalls and a path forward. Altex. 2014;31(3):279–302. doi: 10.14573/altex.1310071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manjili HM. Opinion: translational research in crisis. the-scientist.com; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kola I, Landis J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2004;3(8):711–716. doi: 10.1038/nrd1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.TGR Trends in the risks and benefits to patients with cancer participating in phase 1 clinical trials. JAMA. 2004;292:2130–2140. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.17.2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seok J, et al. Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110(9):3507–3512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222878110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maskus KE, Reichman JH. International public goods and transfer of technology under a globalized intellectual property regime. Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Patent & Trademark Office. Patenting By Geographic Region (State and Country) 2016 http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/naics/stc_naics_fgall/usa_stc_naics_fg.htm.

- 20.Ferguson SM, Kim J. Distribution and licensing of drug discovery tools–NIH perspectives. Drug discovery today. 2002;7(21):1102–1106. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(02)02499-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Natitonal Institutes of Health (NIH) Public-Private Partnerships (For Archival Purposes Only) 2016 https://commonfund.nih.gov/publicprivate.

- 22.Reich MR. Public–private partnerships for public health. Nature Medicine. 2000;6(6):617–620. doi: 10.1038/76176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jack W, Scannell AB. Helen Boldon & Brian Warrington, Eroom’s Law in pharmaceutical R&D. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2012;11:191–200. doi: 10.1038/nrd3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]