Abstract

Japan is an aging society, and the number of elderly patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is consequently increasing, with an estimated incidence of approximately 5 million. In 2014, asthma‐COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) was defined by a joint project of Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) committee and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) committee. The main aims of this consensus‐based document are to assist clinicians, especially those in primary care or nonpulmonary specialties. In this article, we discussed parameters to differentiate asthma and COPD in elderly patients and showed prevalence, clinical features and treatment of ACOS on the basis of the guidelines of GINA and GOLD. Furthermore, we showed also referral for specialized investigations.

Keywords: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, smoking

1. Introduction

Japan is an aging society, and the number of elderly patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is consequently increasing, with an estimated incidence of approximately five million. Although airway inflammation plays a role in the pathogenesis of both diseases, the inflammatory cells found in both and the efficacies of drugs are different. COPD and asthma are considered different diseases with different treatment guidelines.1, 2, 3, 4 However, their clinical symptoms are similar, particularly when they coexist in elderly patients. The coexistence of COPD is a contributing factor for refractory asthma, and therapeutic strategies should be accordingly selected. Items for COPD coexistent with asthma were added to the Japanese COPD Guidelines for Diagnosis and Therapy, third edition, which was released in June 2009.3 The Japanese Asthma Prevention and Control Guidelines, 2012, recommended that asthma with COPD in elderly patients requires early intervention because of a poor prognosis and an early decrease in pulmonary function.1 Asthma in patients with COPD generally shows a late onset and occurs in the presence of a smoking history, while patients with COPD occasionally exhibit risk factors for asthma or asthmatic symptoms. Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish asthma from COPD.

The characteristics of asthma in elderly patients include a decrease in pulmonary function, particularly small airway obstruction, and rapid airway obstruction because of aging, smoking, and airway remodeling. Asthma coexistent with COPD in elderly patients is generally nonatopic and is associated with a high frequency of complications, such as cardiovascular disease, digestive disorders, and metabolic diseases. Other characteristics of asthma in elderly patients include an increased risk of infection because of low immunity or aspiration and a decreased quality of life and adherence to drugs.

Asthma associated with smoking has higher severity, requires more frequent hospital admission, and causes a rapid decrease in the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1.0) compared with asthma not associated with smoking. Furthermore, the efficacy of inhaled or oral corticosteroids is lower for the former than for the latter.

Patients with features of both asthma and COPD have been recognized. They experience frequent exacerbations and have poor quality of life, a more decline in lung function and high mortality than asthma or COPD alone.5, 6 However, there was no generally agreed term or defining features for this category of chronic airway obstruction. In 2014, asthma‐COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) was defined by a joint project of Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) committee and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) committee. The main aims of this consensus‐based document are to assist clinicians, especially those in primary care or nonpulmonary specialties.2, 4 This document also shows ACOS is not a single disease. It includes patients with different forms of airway disease. Therefore, the other aims of this document to stimulate research into ACOS.

In this article, we discuss parameters to differentiate asthma and COPD in elderly patients and management strategies for asthma, COPD, and ACOS on the basis of the guidelines of GINA and GOLD.

2. Diagnosis and Differentiation: Asthma and COPD

The following diagnostic criteria for asthma were proposed by the Japanese Society of Allergology: attacks of dyspnea, wheezing, chest discomfort, and repeated cough (particularly at night and early morning); reversible airway limitation; airway hypersensitivity; history of atopic factor exposure; airway inflammation; and the absence of other diseases.1 COPD is diagnosed when FEV1.0% is <70% after bronchodilator inhalation. However, the assessment of FEV1.0% alone has two limitations. First, it can lead to overestimation of the diagnosis in elderly patients and underestimation in patients with a low vital capacity. Therefore, it is important to judge the severity using both FEV1.0% and %FEV1.0 (FEV1.0/FEV1.0 pred).3, 4

When patients with asthma aged >50 years exhibit symptoms of dyspnea on exertion, cough, sputum, and a history of smoking of >10 pack‐years, the coexistence of COPD should be considered. On the other hand, when patients with COPD report a history of asthma, atopic factor exposure, and attacks of wheezing, cough, and dyspnea at night and in the early morning, the coexistence of asthma should be considered. We often see such patients in the clinic; therefore, awareness of the characteristics of patients with ACOS is important.

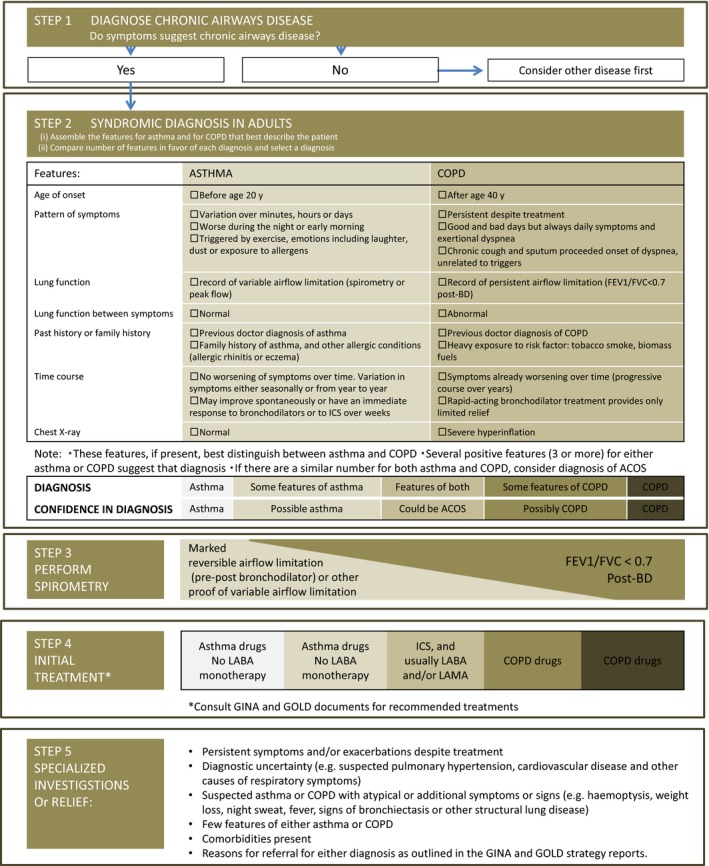

The syndromic diagnosis of asthma, COPD, and ACOS in elderly patients is shown in Table 1.2, 4 Age of onset, pattern of respiratory symptoms, lung function, lung function between symptoms, past history or family history, time course, chest X‐ray, and sputum cell fractionation are used to distinguish asthma from COPD. ACOS has features of both asthma and COPD.

Table 1.

Usual features of asthma, COPD, and ACOS

| Feature | Asthma | COPD | ACOS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset | Usually childhood onset but can commerce at any age | Usually >40 years of age | Usually >40 years of age, but may have had symptoms in childhood or early adulthood |

| Pattern of respiratory symptoms | Symptoms may vary over time (day to day, or over longer periods), often limiting activity. Often triggered by exercise, emotions, dust, or exposure to allergens | Chronic usually continuous symptoms, particularly during exercise, with “better” and “worse” days | Respiratory symptoms including exertional dyspnea are persistent but variability may be prominent |

| Lung function | Current and/or historical variable airflow limitation, for example, BD reversibility, AHR | FEV1 may be improved by therapy, but post‐BD FEV1/FVC <0.7 persists | Airflow limitation not fully reversible, but often with current or historical variability |

| Lung function between symptoms | May be normal between symptoms | Persistent airflow limitation | Persistent airflow limitation |

| Past history or family history | Many patients have allergens and a personal history of asthma in childhood, and/or family history of asthma | History of exposure to noxious particles and gases (mainly tobacco smoking and biomass fuels) | Frequently a history of doctor‐diagnosed asthma (current or previous), allergens and a family history of asthma, and/or a history of noxious exposures |

| Time course | Often improves spontaneously or with treatment, but may result in fixed airflow limitation | Generally, slowly progressive over years despite treatment | Symptoms are partly but significantly reduced by treatment. Progression is usual, and treatment needs are high |

| Chest X‐ray | Usually normal | Severe hyperinflation and other changes of COPD | Similar to COPD |

| Exacerbations | Exacerbations occur, but the risk of exacerbations can be considerably reduced by treatment | Exacerbations can be reduced by treatment. If present, comorbidities contribute to impairment | Exacerbations may be more common than in COPD but are reduced by treatment. Comorbidities can contribute to impairment |

| Airway inflammation | Eosinophils and/or neutrophils | Neutrophils and/or eosinophils in sputum, lymphocytes in airways, may have systemic inflammation | Eosinophils and/or neutrophils in sputum |

ACOS, asthma COPD overlap syndrome; BD, bronchodilator; AHR, airway hyper‐responsiveness; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The differential diagnoses of lung disease include interstitial lung disease, sinobronchial syndrome, bronchiectasis, lung cancer, and respiratory infection, including tuberculosis. Other extrapulmonary differential diagnoses include cardiovascular disease, anemia, obesity, sleep apnea syndrome, and reflex esophagitis. To rule out these diseases, not only efficient medical interviews and examination but also chest radiography, chest computed tomography, electrocardiography, echocardiography, plasma brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) measurement, and sputum culture or cytology are required.

3. Prevalence of ACOS

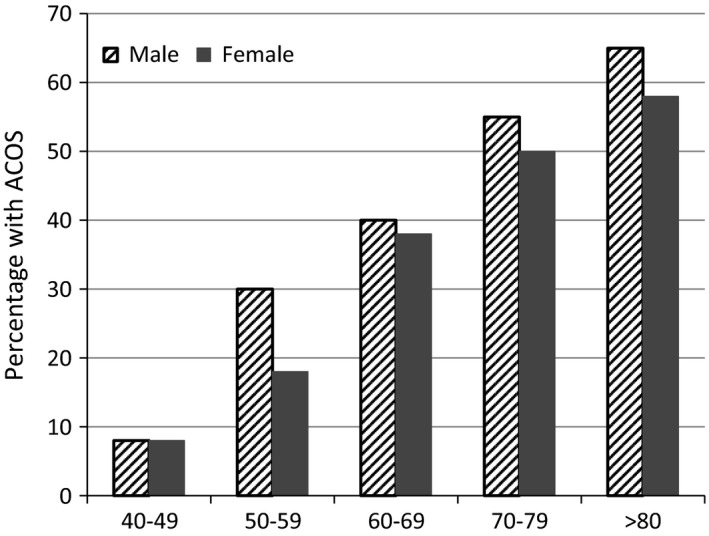

Gibson et al.5 showed prevalence of ACOS patients by gender increased depending on aging. Guidelines2, 4 showed the prevalence rates of ACOS have ranged between 15% and 55%,6, 7, 8 and concurrent doctor‐diagnosed asthma and COPD have been reported in between 15% and 20% of patients.9, 10, 11, 12 In Japan, Nagai et al.13 reported, in 2003, that 37% of patients with asthma showed emphysematous changes. The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare conducted a national survey of asthma to determine its incidence and prevalence and the patient quality of life in 2005.14 In this report, 24.7% of patients with asthma aged >65 years showed COPD. An internet survey of elderly asthma patients in 2008 showed that 48% of elderly patients with asthma exhibited COPD, including emphysema and chronic bronchitis.15

In our institution, 33 of 109 elderly patients with asthma aged >65 years exhibited COPD (33%), while 43 of 188 patients with COPD exhibited asthma (22.8%).

In summary, the prevalence of ACOS was found to be at least 15%.

4. Clinical Features of ACOS

Fabbri et al. reported comparisons between patients with COPD and patients with asthma, who showed irreversible airway obstruction by the age of 65 years. A greater number of patients with COPD reported a smoking history, with a lower DLco and poorer efficacy of long‐acting beta‐2 agonists (LABAs) and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) compared with the patients with asthma.16

The clinical features of asthma in elderly patients and COPD are shown in Table 2 and summarized as follows: (i) The symptoms of asthma in elderly patients include paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and wheezing, while the main symptoms of patients with COPD included dyspnea on exertion. (ii) Patients with asthma reported a history of asthma or atopic factor exposure, while most patients with COPD reported a smoking history. (iii) The lung diffusion capacity assessed by the DLco or DLco/VA, which indicates alveolar function, is normal in patients with asthma and low in COPD patients with severe emphysematous changes. Furthermore, dynamic hyperinflation after hyperventilation or exercise is not observed in patients with asthma, while it is observed even in patients with mild COPD. (iv) Elderly patients with asthma show evidence of eosinophilic airway inflammation in induced sputum, while patients with COPD show evidence of neutrophilic airway inflammation. However, both diseases show a similar cell fraction in induced sputum after exacerbation. (v) FeNO is elevated in steroid‐naïve asthma in elderly patients, while patients with stable COPD show an almost normal FeNO level. (vi) Airway hypersensitivity is usually observed in patients with asthma, but not in patients with COPD. However, it is difficult to differentiate both diseases on the basis of airway hypersensitivity alone. (vii) Not all patients with asthma show an improved FEV1.0% after bronchodilator inhalation. On the other hand, patients with COPD show an FEV1.0% of <70% after bronchodilator inhalation. LABAs are more effective in asthma than in COPD, while long‐acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) are more effective in COPD than in asthma. Of late, patients with COPD have been exhibiting reversibility after inhalation of two bronchodilator doses. However, LABAs and ICS are more effective in patients with asthma than in patients with COPD. (viii) Emphysematous changes, which appear as low‐attenuation areas on high‐resolution computed tomography, are observed in COPD, but not in asthma.

Table 2.

Clinical features of asthma and COPD

| (1) Symptoms |

Paroxysmal nocturnal cough, dyspnea, and wheezing (Asthma) Dyspnea on exertion, chronic cough, and sputum (COPD) |

| (2) Clinical history |

History of asthma, atopic factor (Asthma) Middle aged or older, smoking history of over 10 pack‐year (COPD) |

| (3) Pulmonary function tests |

Small airway disease (Asthma·COPD) Low lung diffusion capacity, pulmonary hyperinflation (COPD) |

| (4) Sputum cell fractionation |

Eosinophilic airway inflammation (Asthma) Neutrophilic airway inflammation (COPD) |

| (5) Exhaled nitric oxide levels |

High (Asthma) Normal (COPD) |

| (6) Airway hypersensitivity | Hyper (Asthma≧COPD) |

| (7) Efficacy of drugs |

Bronchodilator (Asthma·COPD) Inhaled corticosteroid (Asthma) |

| (8) HRCT | Low attenuation area (COPD) |

HRCT, high‐resolution computed tomography; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

ACOS patients are considered to exhibit the clinical features of both diseases. Therefore, we always need to consider the coexistence of COPD and asthma in elderly patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage with Asthma‐COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) among the patients with airflow obstruction. Each age group was divided by gender. Prevalence of ACOS patients was increased by age

5. Treatment of Syndromic Diagnosis of ACOS

Smoking cessation is the first step of management for smokers. It decreases the symptoms of wheezing, cough, sputum, and dyspnea and disease severity and improves the patient's quality of life. It also improves airway inflammation and airway obstruction, which leads to prevent a rapid decrease in FEV1.0. Smoking cessation improves the efficacy of ICS and theophylline clearance.17

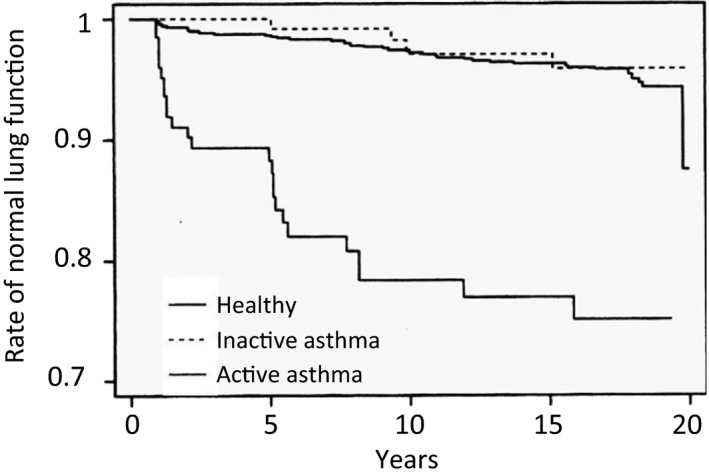

Active asthma without COPD decreased pulmonary function compared with inactive asthma. To obtain good control of asthma is very important to maintain lung function; therefore, the use of ICS is strongly recommended for patients with asthma to obtain better control (Figure 2).18 Pulmonary function shows a more rapid decrease in ACOS patients than in patients with COPD. Therefore, ICS are recommended for ACOS patients by the Japanese COPD guidelines, irrespective of the severity of COPD or Global initiative chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage of airway obstruction.3, 4

Figure 2.

Annual change of pulmonary functions in healthy control, inactive asthma, and active asthma. Active asthma patients decline their lung function compared to inactive asthma

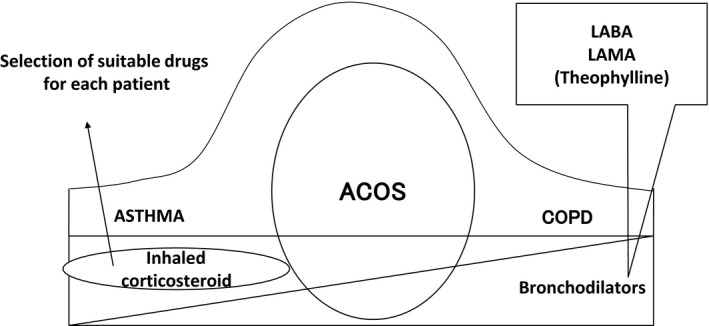

A combination of ICS and bronchodilators, LAMA, or LABA is the recommended pharmacological therapy for ACOS (Figure 3).19 ICS are first‐choice drugs for asthma, including asthma in elderly patients. There are two types of ICS devices: dry powder inhaler (DPI) and metered dose inhaler (MDI). MDIs are pressurized canisters. When the inhaler is pressed while breathing in, vapor containing the medication passes into the lungs. DPIs contain the medication in the dry powder form. The powder must be inhaled quickly and forcefully for the medication to reach the lungs. The particles delivered by MDIs are smaller than those delivered by DPIs, and MDIs can access smaller airways compared with DPIs. Because most ACOS patients exhibit small airway involvement, MDIs such as beclomethasone hydrofluoroalkane or ciclesonide hydrofluoroalkane are more effective.20 It is reported that both MDIs and DPIs are adequate for COPD, even severe COPD. Subgroup analysis of the GOAL21 and TORCH22 study results showed that the combination of fluticasone and salmeterol, which are DPIs, was effective for both asthma in elderly patients and COPD. It is important to select ICS devices for ACOS patients on the basis of the inhalation technique, device type, and patient compliance.

Figure 3.

Drug therapy of Asthma‐COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS), asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A combination of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and bronchodilators, long‐acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA), or long‐acting beta‐2 agonists is the recommended pharmacological therapy for ACOS. ICS are first‐choice drugs for asthma, while LAMAs are first‐choice drugs for COPD

Variations of long‐acting bronchodilators include inhaled LAMAs such as tiotropium and glycopyrronium; inhaled LABAs such as salmeterol, formoterol, and indacaterol; and patched LABAs such as tulobuterol and oral theophylline. Recently, a combination of inhaled LABAs and LAMAs, such as glycopyrronium/formoterol and umeclidinium/vilanterol, has become available in Japan. Symptoms, drug effects, side effects and complications should be considered when selecting combination therapy of LABAs and LAMAs. Although each drug has different mechanisms of inducing bronchodilation, appropriate treatment not only improves symptoms, exercise capacity, and quality of life but also prevents exacerbation.

LAMAs are first‐choice drugs for COPD, although they are also effective for asthma with dyspnea on exertion. The addition of tiotropium improves pulmonary function and quality of life in elderly patients with asthma controlled by ICS and LABAs.23 Elderly patients who cannot inhale drugs properly are suitable for tulobuterol patches because of good compliance and improvement in quality of life. Downregulation of beta‐2 receptors occurs by the administration of LABAs alone, even in elderly patients, while ICS suppress this downregulation. Therefore, administration of both ICS and LABAs may be effective. The combined administration of ICS and LABAs is easier compared with the separate administration of each drug, and it is expected to lead to higher patient compliance. Furthermore, low‐dose theophylline (serum level: approximately 5 μg/mL) has shown anti‐inflammatory effects when combined with bronchodilators. However, serum theophylline levels should be measured, particularly in patients with several complications, to prevent theophylline intoxication. Smoking increases leukotriene production in patients with asthma; it has been reported that leukotriene receptor antagonists are more effective than ICS for asthma associated with smoking.24

The daily activities of ACOS patients are decreased because of dyspnea on exertion. This results in deconditioning and decreased cardiac function and skeletal muscle wasting, which, in turn, leads to less exercise and deterioration of dyspnea, thus creating a vicious circle. To resolve this issue, pulmonary rehabilitation and appropriate respiration techniques and drug administration are recommended; short‐acting bronchodilators administered before exercise are also effective.

In summary, ACOS patients should receive a combination of ICS and long‐acting bronchodilators LABAs and/or LAMAs after considering the risks and benefits. Depending on the symptoms or severity of disease, other medications or early pulmonary rehabilitation should be additionally considered.

6. Referral for Specialized Investigations

Referral for expert advice and further diagnostic evaluation is necessary in the following contexts (Figure 4): (i) Patients with persistent symptoms and/or exacerbations despite treatment; (ii) diagnostic uncertainty, especially if an alternative diagnosis including suspected pulmonary hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and other causes of respiratory symptoms, needs to be excluded; (iii) patients with suspected asthma or COPD with atypical or additional symptoms or signs (eg, hemoptysis, weight loss, night sweat, fever, signs of bronchiectasis, or other structural lung disease) suggest an additional pulmonary diagnosis;(iv) when chronic airways disease is suspected but syndromic features of both asthma and COPD are few; (v) comorbidities present; (vi) referral may be appropriate for issues arising during ongoing management of asthma, COPD, or ACOS, as outlined in the GINA and GOLD strategy reports.2, 4

Figure 4.

Guidelines of Global Initiative for Asthma and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease showed syndromic approach to disease of chronic airflow limitation. This approach showed from diagnosis of chronic airway disease (STEP 1) to referral for specialized investigations (STEP 5)

In summary, when diagnosis is uncertain or symptoms are atypical or continue in spite of appropriate treatment of ACOS by guidelines’ recommendations, referral for specialized investigation is needed.

Conflict of Interest

KH has received funds reimbursing him for attending a related symposia, or talk from Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi‐Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Kyorin Pharmaceutical, and Novartis Pharma. Institution of YT, KA, and KH has received research funding from Astellas Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Kyorin Pharmaceutical, and MSD. TS has no conflict of interest.

Tochino Y, Asai K, Shuto T, Hirata K. Asthma‐COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS)—Coexistence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma in elderly patients and parameters for their differentiation. J Gen Fam Med. 2017;18:5–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgf2.2

References

- 1. Ohta K, Akiyama K, Nishima S, et al. The Japanese Society of Allergology: The Japanese Asthma Prevention and Management Guideline 2012. Tokyo: Kyowa Kikaku; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, Boulet LP, et al. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. [Updated 2015]. Available from http://www.ginasthma.org/local/uploads/files/GINA_Report_2015_May19.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- 3. Nagai A, Nishimura M, Mishima M, et al. The Japanese Respiratory Society: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 4th ed Osaka: Medical Review; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Decramer M, Agusti AG, Bourbeau J, et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. [Updated 2015]. Available from http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report_2015_Apr2.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- 5. Gibson PG, Simpson JL. The overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD: what are its features and how important is it? Thorax. 2009;64:728–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kauppi P, Kupiainen H, Lindqvist A, et al. Overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD predicts low quality of life. J Asthma. 2011;48:279–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marsh SE, Travers J, Weatheall M, et al. Proportional classification of COPD phenotypes. Thorax. 2008;63:761–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weatheall M, Travers J, Shirtcliffe PM, et al. Distinct clinical phenotypes of airways disease defined by cluster analysis. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:812–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, Lydick E. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1683–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Louie S, Zekki AA, Schivo M, et al. The asthma‐chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome: pharmacotherapeutic considerations. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:197–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McDonald VM, Simpson JL, Higgins I, Gibson PG. Multidimensional assessment of older people with asthma and COPD: clinical management and health status. Age Ageing. 2011;40:42–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Soriano JB, Davis KJ, Coleman B, et al. The proportional Venn diagram of obstructive lung disease: two approximations from the United States and the United Kingdom. Chest. 2003;124:474–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nagai A, Tamaoki J. Coexistence of COPD as a factor of severe asthma. Arerugi No Rinsho. 2003;2:154–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Akazawa A, Takahashi K, Taniguchi M, et al. National survey in all ages about prevalence of asthma, effect of expanding guideline and quality of life. The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Grants System; Available from www.allergy.go.jp/Research/Shouroku_08/16akazawa.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Minoguchi K, Yokoe T, Tanaka A, et al. Current treatment of asthma and its problems from the Internet survey of adult asthma patients. Allergol Immunol. 2009;16:72–81. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fabbri LM, Romaqnoli M, Corbetta L, et al. Differences in airway inflammation in patients with fixed airflow obstruction due to asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:418–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thomson NC, Chaudhuri R, Livingston E. Asthma and cigarette smoking. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:822–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Silva GE, Sherrill DL, Guerra S, Barbee RA. Asthma as a risk factor COPD in a longitudinal study. Chest. 2004;126:59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tochino Y, Asai K, Hirata K. Bronchial asthma: progress in diagnosis and treatments. Topics: I. Basic knowledge; 4. Differentiation and coexistence with COPD. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2013;102:1352–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leach CL, Davidson PJ, Hasselquist BE, Boudreau RJ. Lung deposition of hydrofluoroalkane‐134a beclomethasone is greater than that of chlorofluorocarbon fluticasone and chlorofluorocarbon beclomethasone: a cross‐over study in healthy volunteers. Chest. 2002;122:510–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bateman ED, Bousquet J, Keech ML, Busse WW, Clark TJ, Pedersen SE. The correlation between asthma control and health status: the GOAL study. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. Cardiovascular events in patients with COPD: TORCH study results. Thorax. 2010;65:719–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hirata K. Treatment of inhaled drugs for asthma, role of long‐acting muscarinic antagonists. J Japan Soc Respir Care. 2006;15:605–11. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lazarus SC, Chinchilli VM, Rollings NJ, et al. Smoking affects response to inhaled corticosteroids or leukotriene receptor antagonists in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:783–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]