Abstract

Black young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (YGBMSM) are at high risk for negative health outcomes, though this population is underrepresented in the health literature. An extensive literature review and content analysis of health-related peer-reviewed articles (1988-2013) was conducted that targeted Black YGBMSM, examining five content areas: sexual health, health care, substance use, psychosocial functioning, and sociostructural factors. A coding sheet was created to collect information on all content areas and related subtopics and computed descriptive statistics. Out of 54 articles, most were published after 2004 (N = 49; 90.7%) and addressed some aspect of sexual health (N = 50; 92.6%). Few articles included content on psychosocial functioning, including bullying/harassment, suicide, and racial/ethnic identity. Data on health care delivery/receipt and health insurance were underrepresented; tobacco use and substance abuse were seldom addressed. Important sociostructural factors, including sexual networks and race-based discrimination, were poorly represented. Last, there was a noteworthy deficit of qualitative studies and research exploring intersectional identity and health. This review concludes that studies on Black YGBMSM health places sex at the forefront to the neglect of other critical health domains. More research is needed on the diverse health issues of a vulnerable and underexamined population.

Keywords: gay health issues, adolescence, men of color, psychosocial and cultural issues, behavioral issues

Introduction

The health and well-being of adolescents and young adults has been an area of prominent focus in public health. This developmental period is marked by the negotiation of complex intrapersonal, interpersonal, and broader social experiences, and is further influenced by the varied cultural, environmental, and sociopolitical settings in which adolescents are situated (Crockett, 1997; Deas, 2005; Smetana, Campione-Barr, & Metzger, 2006). These factors serve to contextualize behavioral health risk and health outcomes for adolescents and young adults. Such outcomes include, but are not limited to, substance abuse and dependence, sexual health, and psychosocial functioning (Bennett & Bauman, 2000; Countryman, 2012; Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Shrier, Harris, Sternberg, & Beardslee, 2001; Viner et al., 2012).

While these health concerns are applicable to youth as a whole, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT), and other nonheterosexually identified youth may face additional challenges related to health. Researchers have reported that LGBT adolescents have considerably higher rates of substance use when compared with heterosexual adolescents, and that substance use is also associated with sexual risk taking and suicide attempts among gay and bisexual youth (Jordan, 2000; Marshal et al., 2008; Remafedi, 1994; Remafedi, Farrow, & Deisher, 1991; Rotheram-Borus et al., 1994). Furthermore, LGBT adolescents have much higher rates of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide completion when compared with heterosexual youth (Haas et al., 2010; Russell & Joyner, 2001; Suicide Prevention Resource Center, 2008). In addition, LGBT youth often experience discrimination and abuse on the basis of sexual orientation in a variety of contexts, including school, family, and community settings (Birkett, Espelage, & Koenig, 2009; Friedman, Marshal, Stall, Cheong, & Wright, 2008; Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Kosciw, Greytak, & Diaz, 2009; Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009; Sullivan & Wodarski, 2002). Consequently, many researchers have demonstrated that maintaining psychological health is especially challenging for this population (D’Augelli, 2002; Halverson, 2005; Rotheram-Borus & Fernandez, 1995). It is important to note, however, that high rates of negative health outcomes are not due to any inherent dysfunction among LGBT youth; rather, these outcomes are likely related to being members of a socially stigmatized group, who experience prejudice-related stressful life events, ongoing discrimination, and expectations of rejection (Harper & Schneider, 2003; Institute of Medicine, 2011; Meyer, 2003). Taken together, these concerns highlight a need for continued research that addresses psychosocial functioning, but also speaks to a need to examine the social determinants that give rise to adverse health outcomes.

Sexual health is another important health domain for LGBT adolescents. Young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (YGBMSM) in particular are at elevated risk for adverse sexual health outcomes. YGBMSM between the ages of 13 and 24 years have been experiencing an increase in rates of HIV infection, in spite of the fact that HIV incidence has been on a nationwide decline (Centers for Disease Control, 2013; Hall, Byers, Ling, & Espinoza, 2007). Researchers have reported that HIV risk is elevated in the presence of other psychosocial health problems, including substance use, mental health, and intimate partner violence (Bruce, Harper, & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions, 2011; Mustanski, Garofalo, Herrick, & Donenberg, 2007). YGBMSM also have nuanced experiences across a number of general sexual health categories that may have important implications for sexual health outcomes, including age of partners, race of partners, sexual positioning (e.g., being the receptive or insertive partner during anal sex), and online partner seeking (Bauermeister, 2012; Bruce, Harper, Fernandez, Jamil, & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions, 2012; Meyer & Dean, 1995; Millett, Peterson, Wolitski, & Stall, 2006; Mustanski & Newcomb, 2013).

When examining health outcomes for gay and bisexual youth across racial/ethnic categories, the factors associated with health disparities become increasingly complex. Black YGBMSM face even more challenges across multiple health domains, and researchers have proposed that these challenges are likely associated with African Americans’ experiences of marginalization and oppression on the basis of race (Mays, Cochran, & Barnes, 2007; Williams, 1999). With regard to HIV risk, Black YGBMSM accounted for more than half of new HIV infections among YGBMSM in 2010, and rates of HIV infection continue to be disproportionately represented among this population (Centers for Disease Control, 2011, 2013; Hall et al., 2007; Harawa et al., 2004). Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)—including syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia—are noted to be higher among Black GBMSM, which may in turn predispose this population to greater risk for HIV infection (Millett et al., 2006; Newman & Berman, 2008; Su, Beltrami, Zaidi, & Weinstock, 2011). Moreover, HIV-positive Black GBMSM are less likely to receive treatment or see a health care provider shortly after being diagnosed, and are also less likely to have health insurance than other HIV-positive GBMSM (Ebrahim, 2004; Millett et al., 2012; Oster, Dorell, et al., 2011; Oster, Wiegand, et al., 2011).

Although Black YGBMSM have higher rates of HIV infection, they do not engage in more individual risk behaviors compared with non-Black YGBMSM (Millett et al., 2006). Furthermore, some researchers have identified that Black GBMSM engage in less individual risk behaviors compared with other racial/ethnic groups, which suggests that individual behavior does not account for the differences observed in HIV infection across racial/ethnic groups (Calabrese, Rosenberger, Schick, Novak, & Reece, 2013; Harawa et al., 2004; Magnus, Kuo, et al., 2010; Magnus, Jones, et al., 2010). Researchers have thus highlighted a number of sociostructural factors that may be associated with Black GBMSM’s elevated risk for HIV infection, including fundamental health determinants (i.e., stigma, discrimination, racism), community factors (e.g., sexual networks, housing, social/peer networks), and access to health education, health care, and preventive health services (Clerkin, Newcomb, & Mustanski, 2011; Cohall et al., 2010; Dorell et al., 2011; George, Phillips, McDavitt, Adam, & Mutchler, 2012; Hightow-Weidman, Jones, Phillips, Wohl, & Giordana, 2011; Maulsby et al., 2014; Millett et al., 2006; Natale, 2009; Warren et al., 2007). Many of these factors remain hypothetical as few empirical studies have explored the relationship between HIV infection and macro-level variables that may influence health outcomes (Maulsby et al., 2014; Millett et al., 2006). In an effort to develop prevention and intervention initiatives tailored to the specific needs of Black YGBMSM, it will be important for HIV researchers to examine community, cultural, and sociostructural correlates of HIV risk within this population.

In addition to sexual health risk, many important nonsexual health domains for Black YGBMSM—such as mental health and intersectional identity development across marginalized groups (e.g., Black and gay)—are underrepresented in the literature (Jamil, Harper, & Fernandez, 2009; Mustanski, Garofalo, & Emerson, 2010). It is essential, however, to consider the needs and experiences of Black YGBMSM holistically, especially when this population continues to suffer disproportionate rates of negative health outcomes. Given the importance of assessing the state of knowledge about this population’s health needs, the investigators conducted an integrative literature review and content analysis of current health literature targeting Black YGBMSM. The investigators examined a broad scope of health domains for this population, covering five substantive content areas: (a) sexual health, (b) health care, (c) substance use, (d) psychosocial functioning, and (e) sociostructural factors. This article identifies gaps in the literature on Black YGBMSM, synthesizes and consolidates empirical findings addressing health disparities among Black YGBMSM, and informs future directions for research among this population.

Method

Procedure

This study employed an integrative review process and content analysis as its principal methodological and data analytic approach (Krippendorf, 2013; Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). The review was initiated by using three scholarly search engines—PubMed, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar—to examine the current literature related to the selected topic. To conduct the search, a combination of three specific keywords were entered from the following list: “Black,” “Gay,” “Youth,” “Adolescents,” “MSM,” and “African-American.” Each combination included a race, age, and sexual orientation term (e.g., Black + Adolescents + Gay). The first 100 results from each search term combination on Google Scholar were checked for a total of 800 search results. All search results that appeared in the PubMed and PsycINFO search engines were checked. Across all search engines, duplicate citations were quickly identified and avoided due to browser settings that highlight previously clicked links in a different color. Articles were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (a) The study sample had to be based in the United States; (b) At least 75% of the sample had to be male and include analysis and discussion specific to male gender; (c) At least 50% of the sample had to be between the ages of 13 and 25 years and include analysis and discussion specific to this age range; (d) The sample had to include men reporting a nonheterosexual orientation or identity (e.g., gay/bisexual) or men reporting having engaged in sexual activity with other men; (e) The article had to include enough participants who were Black (or represented a racial categorization across the African Diaspora) to conduct race-specific analyses; (f) The article had to include a substantive focus on some aspect of health (e.g., sexual health, psychosocial functioning); and (g) The article had to be published between 1988 and 2013 inclusive.

In addition to the above criteria, articles with a mixed gender sample that did not provide a clear breakdown of race and/or sexual identity by gender were excluded from the analysis. The investigators also elected to include articles with racially/ethnically diverse samples in order to capture the broad scope of health research relevant to the study population. However, in order to ensure a sufficient number of Black participants for meaningful ethnic-specific analysis, the investigators developed cutoff criteria for the proportion of Black participants per article in relation to the total sample size of the study: (a) For articles with an N ≤ 100, Black participants had to account for ≥40% of the total sample; (b) For articles with an N between 100 and 250, Black participants had to account for ≥30% of the total sample; (c) For articles with an N between 250 and 500, Black participants had to account for ≥25% of the total sample; and (d) For articles with an N ≥ 500, Black participants had to account for ≥20% of the total sample.

Content Coding

A content analysis coding and data sheet was created to gather information on demographics, recruitment strategies, research methods used in each article, the five core content areas related to health, and related subtopics within each content area. All articles were coded for their inclusion or omission of each content area topic and subtopic, where 1 = inclusion of content and 0 = omission of content.

Demographics

Six race/ethnicity identity labels were selected and recorded. These labels included (a) Black/African American, (b) White/Caucasian, (c) Latino/Hispanic, (d) Asian/Pacific Islander, (e) other, and (f) not specified. For sexual orientation, the investigators recorded every sexual identity label used by the authors and identified 26 identity labels in total. Many of these labels included combined identity terms (e.g., homosexual/gay, bisexual/bicurious, straight/unsure, etc.) that overlapped with singular identities (e.g., gay, bisexual, straight, etc.). Through a thematic analysis process, the comprehensive set of identity labels were collapsed into a smaller set of similar categories. In total, 10 sexual orientation identity labels were selected to be represented in the review: (a) gay, (b) bisexual, (c) straight, (d) straight/unsure/other, (e) MSM, (f) MSM/nongay identified, (g) down-low, (h) questioning, (i) two-spirited, and (j) other.

Core Content Codes

The investigators coded for recruitment strategies and research methodologies employed in each article; a list of these are noted on Table 1. The investigators coded for five substantive areas of health with each content area including a set of specific topics and subtopics. All topics for sexual health, health care, and substance use are listed on Table 2, and all topics for psychosocial functioning and sociostructural factors are listed on Table 3.

Table 1.

Article Characteristics, Demographics, Recruitment, and Methodology.

| N (participants) | % | N (articles) | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article characteristics | ||||

| Male exclusivea | — | — | 50 | 92.6 |

| Age range (13-25 years) exclusive | — | — | 47 | 87.0 |

| Black/African American exclusive | — | — | 22 | 40.7 |

| All Black men, aged 13-25 years | — | — | 18 | 33.3 |

| Sexual identities | ||||

| Gay | 22,126 | 38.7 | 25 | 46.3 |

| Bisexual | 6,577 | 11.5 | 28 | 51.9 |

| Straight | 139 | 0.2 | 8 | 14.8 |

| Straight/unsure/other | 394 | 0.7 | 2 | 3.7 |

| MSMb | 25,297 | 44.3 | 16 | 29.6 |

| MSM/nongay identified | 289 | 0.5 | 2 | 3.7 |

| Down-low | 12 | <0.1 | 2 | 3.7 |

| Questioning | 123 | 0.2 | 3 | 5.5 |

| Two-spiritedc | 106 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other | 2,039 | 3.6 | 18 | 33.3 |

| Racial/ethnic identities | ||||

| Black/African American | 25,124 | 41.5 | — | — |

| White/Caucasian | 14,175 | 23.4 | — | — |

| Latino/Hispanic | 15,947 | 26.4 | — | — |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2,253 | 3.8 | — | — |

| Other | 2,618 | 4.3 | — | — |

| Not specified | 391 | 0.7 | — | — |

| Dichotomized—Racial/ethnic identities | ||||

| Black/African American | 25,124 | 41.5 | — | — |

| Non-Black/African American | 35,384 | 58.5 | — | — |

| Recruitment | ||||

| School based | — | — | 0 | 0 |

| Community based | — | — | 49 | 90.7 |

| Online | — | — | 6 | 11.1 |

| Databases | — | — | 3 | 5.5 |

| Methodology | ||||

| Qualitative | ||||

| Individual | — | — | 9 | 16.7 |

| Focus groups | — | — | 5 | 9.3 |

| Other | — | — | 1 | 1.9 |

| Quantitative | ||||

| Individual | — | — | 45 | 83.3 |

| Other | — | — | 1 | 1.9 |

Note. MSM = men who have sex with men.

One article had seven transidentified participants (male to female); one article had two participants identified as female, two identified as transgender, and two identified as other/refused; one article had four transidentified participants who were assigned male at birth and reported having sex with men; and one article had a mixed gender sample with a large sample size (N > 4,000). bMay include gay-identified and nongay-identified participants. cTwo articles included two-spirited as part of a joint identity (e.g., queer/two-spirited); no article included it as a stand-alone label.

Table 2.

Sexual Health, Health Care, and Substance Abuse.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual health | ||

| HIV | 38 | 70.4 |

| HIV testing/counseling | 12 | 22.2 |

| HIV knowledge/treatment awareness | 6 | 11.1 |

| HIV status (participants) | 32 | 59.3 |

| HIV status (partners) | 9 | 16.7 |

| HIV status disclosure | 3 | 5.6 |

| ART use/viral load/CD4 Counts | 8 | 14.8 |

| Linkage/retention in care | 5 | 9.3 |

| HIV stigma | 2 | 3.7 |

| STIsa | 10 | 18.5 |

| Sexual activityb | 40 | 74.1 |

| Condom usagec | 39 | 72.2 |

| General sexual health | 42 | 77.8 |

| Peer norms around condoms | 8 | 14.8 |

| Exchange sex for resources | 13 | 24.1 |

| Sex education or prevention programs | 12 | 22.2 |

| Sexual positioning/roled | 20 | 37.0 |

| Age at sexual debute | 10 | 18.5 |

| Age of partners | 8 | 14.8 |

| Race of partners | 4 | 7.4 |

| Relationship typef | 15 | 27.8 |

| Online/app-based partner seeking | 7 | 13.0 |

| Sexual violence | 2 | 3.7 |

| Health care | ||

| Health care receipt/delivery | 8 | 14.8 |

| Health insurance | 7 | 13.0 |

| Substance use | ||

| Alcohol | 16 | 29.6 |

| Tobacco | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other drugs | 28 | 51.9 |

| Substance abuse | 2 | 3.7 |

Note. STIs = sexually transmitted infections; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

Includes having ever contracted/tested for STIs. bIncludes number of partners, type of sex acts (anal, oral, vaginal), frequency of sex acts, abstinence, and gender of partner. cIncludes use and negotiation. dIncludes insertive/receptive anal sex or top/bottom/versatile sexual roles. eIncludes age at first sexual experience and/or age at first same-sex experience. fIncludes main/nonmain partners, steady/nonsteady partners, and primary/casual/committed partners.

Table 3.

Psychosocial Functioning and Sociostructural Factors.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial functioning | ||

| Stress | 3 | 5.6 |

| Anxiety | 2 | 3.7 |

| Depression | 10 | 18.5 |

| Coping | 2 | 3.7 |

| Suicide | 4 | 7.4 |

| Bullying/harassment | 2 | 3.7 |

| Abuse | 2 | 3.7 |

| Social support | 10 | 18.5 |

| Self-efficacy/self-esteem/self-worth | 5 | 9.3 |

| Racial/ethnic identity | 6 | 11.1 |

| Sexual orientation identity | 24 | 44.4 |

| Gender expression/identity | 4 | 7.4 |

| Sociostructural factors | ||

| Homophobia | 9 | 16.7 |

| Attitudes | 6 | 11.1 |

| Discrimination | 6 | 11.1 |

| Racism | 4 | 7.4 |

| Attitudes | 1 | 1.9 |

| Discrimination | 3 | 5.6 |

| Stigma | 2 | 3.7 |

| Sexuality | 2 | 3.7 |

| Race | 1 | 1.9 |

| Social/environmental context | 19 | 35.2 |

| Community/neighborhood characteristics | 7 | 13.0 |

| Sexual networks | 3 | 5.6 |

| General peer/social networks | 8 | 14.8 |

| Church/religion/ideology | 3 | 5.6 |

| Housing/living arrangement | 6 | 11.1 |

| Family experiences | 4 | 7.4 |

Data Analytic Strategy

The analytic strategy was informed using previously established guidelines around quantitative content analysis (Krippendorf, 2013). For each article, information on (a) the mean age of sample participants when provided, (b) the total number of participants in each racial/ethnic group category, and (c) the total number of participants in each sexual orientation identity category was collected. In some instances, researchers only provided the percentage of participants identifying with each racial/ethnic identity and sexual orientation identity label. For these cases, the N was calculated by multiplying the percentage by the total sample size and rounded to the nearest whole number. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for all content areas, all topic and subtopic content codes and all demographic categories. Last, the number of articles published per year in the target date range were collected as well as overall percentages for each year.

Results

Article and Sociodemographic Characteristics

In total, 54 articles were identified that met the inclusion criteria, which is an approximate average of two articles per year (all articles included in the review are denoted with an asterisk in the references section). Precisely one third of the articles reviewed captured data exclusively for Black YGBMSM between the ages of 13 and 25 years (see Table 1). A total of 22 articles (41.2%) were Black exclusive, 47 articles (87.0%) included sample data exclusively for participants between the ages of 13 and 25 years, and 50 articles (92.6%) included samples that were exclusively male. Only 38 articles (70.4%) included data on the mean age of participants. Of these, the mean age of participants was 20.74 years (SD = 2.20). Of the articles with a mixed gender sample, one included seven transidentified participants (male to female). Another article included two participants who identified as female, two who identified as transgender, and two who identified as “other/refused.” A third article included four transidentified participants who were assigned male at birth and reported having sex with men. The fourth mixed gender article had a sufficiently large enough sample size (N > 4,000) to meet the inclusion criteria for age, race, and male gender.

Approximately two fifths (41.5%) of all sampled participants were categorized as Black/African American, with very few studies (3.7%) noting any distinction on basis of ethnic/cultural background (e.g., Caribbean, African, etc.). A sizable portion (44.3%) of all sampled participants were categorized exclusively as MSM by the researchers without any other accompanying identity label. MSM that were strictly nongay identified composed 0.5% of the total sample. In contrast, 38.7% of all sampled participants were categorized as gay and 11.5% identified as bisexual. Considerably fewer participants were categorized as straight (0.2%), straight/unsure/other (0.7%), down-low (<0.1%), questioning (0.2%), two-spirited (0.2%), and other (3.6%).

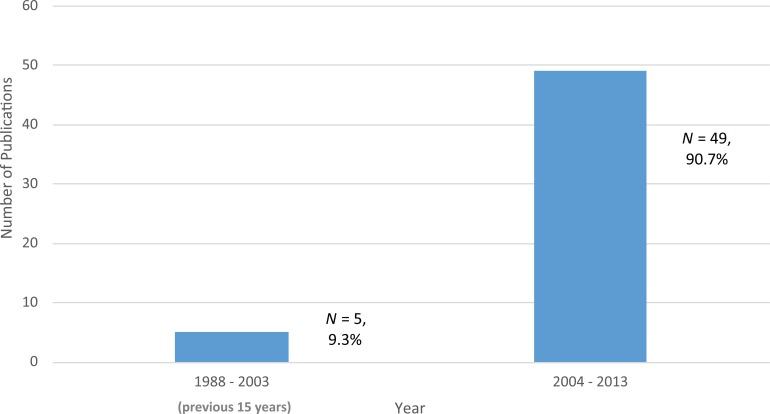

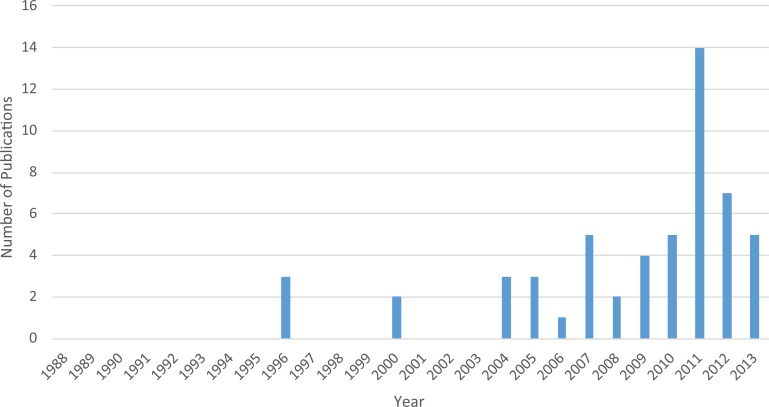

No article included a school-based venue for recruitment. The majority of researchers recruited participants through community venues (N = 49, 90.7%), while a small number of researchers used online recruitment methods (N = 6, 11.1%) or collected sample data through large national or state-level databases (N = 3, 5.5%). Most articles included quantitative methods and analyses (N = 46, 85.2%), while a smaller number of articles employed qualitative methods in their research design and analytic approach (N = 15, 27.8%). Last, there was a pronounced skew in the distribution of publication dates over time. A total of 49 articles (90.7%) were published in the past 10 years, while only 5 articles (9.3%) were published in the previous 15 years (see Figure 1). More articles were published in 2011 (N = 14, 25.9%) than any other year and accounted for approximately one quarter of all publications in this 25-year review (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Publications on Black YGBMSM and health (1988-2013).

Note. YGBMSM = young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.

Figure 2.

Publications on Black YGBMSM and health (1988-2013).

Note. YGBMSM = young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.

Sexual Health

Overall, almost all of the articles in the review included content on sexual health (N = 50, 92.6%). Nearly three fourths of the articles included data on some aspect of HIV (N = 38, 70.4%). Of the HIV-specific subtopics, nearly one fourth of the articles included content on HIV testing and counseling (N = 12, 22.2%). More than half of the articles contained data on the HIV status of study participants (N = 32, 59.3%), though far fewer contained data on the HIV status of participants’ partners (N = 9, 16.7%). A small number of articles included data on HIV knowledge and treatment awareness (N = 6, 11.1%), as well as linkage and retention in care (N = 5, 9.3%), and antiretroviral therapy (ART) use, viral load, and CD4 counts (N = 8, 14.8%). Only three articles (5.6%) included data on status disclosure, and two articles (3.7%) included content on HIV stigma (see Table 2).

Slightly less than one fifth of the articles included data on participants’ STI history (N = 10, 18.5%), while nearly three fourths of the articles included data on condom use (N = 39, 72.2%) and sexual activity (N = 40, 74.1%). Approximately four fifths of the articles included content on some aspect of general sexual health (N = 42, 77.8%). Of the general sexual health subtopics, more than a third of the articles included data on sexual positioning or role (N = 20, 37.0%). Roughly a quarter of the articles included data on relationship type (N = 15, 27.8%), exchanging sex for resources (N = 13, 24.1%), and sex education or prevention programs (N = 12, 22.2%). Nearly one fifth of the articles included data on participants’ age at sexual debut (N = 10, 18.5%), while eight articles (14.8%) included content on peer norms around condoms. A small number of articles included content on age of participants’ partners (N = 8, 14.8%), race of participants’ partners (N = 4, 7.4%), sexual violence (N = 2, 3.7%), and online or app-based partner seeking (N = 7, 13.0%).

Health Care and Substance Use

Overall, 10 of the articles (18.5%) in the review included content on health care. Eight articles (14.8%) included content on the delivery or receipt of health care services and seven articles (13.0%) contained data on whether or not participants had health insurance. Almost half of the articles in the review included content on substance use (N = 28, 51.9%). Slightly more than a quarter of the articles contained data on alcohol use (N = 16, 29.6%). No article included data on tobacco use, and only two articles (3.7%) made explicit mention of substance abuse. Approximately half of the articles contained data on the use of other drugs (N = 28, 51.9%) with other drugs accounting for 60.9% of all substance use content codes (see Table 2).

Psychosocial Functioning

Approximately two thirds of the articles reviewed included content on some aspect of psychosocial functioning (N = 35, 64.8%). Nearly half of the articles included content on sexual orientation identity (N = 24, 44.4%), and altogether, sexual orientation identity accounted for 32.4% of all psychosocial functioning content codes (see Table 3). Nearly one fifth of the articles included content on social support (N = 10, 18.5%) and depression (N = 10, 18.5%). Six articles (11.1%) contained content on racial/ethnic identity, but only four articles (7.4%) included content on gender expression. Considerably fewer articles contained content on abuse (N = 2, 3.7%) and bullying/harassment (N = 2, 3.7%), and the same was true for coping (N = 2, 3.7%) and self-efficacy/self-esteem/self-worth (N = 5, 9.3%). Last, content on stress (N = 3, 5.6%), anxiety (N = 2, 3.7%), and suicide (N = 4, 7.4%) were also poorly represented in the literature.

Sociostructural Factors

Approximately two fifths of the articles reviewed included content on sociostructural factors (N = 23, 42.6%), and nearly a third of the articles included content on some aspect of social/environmental context (N = 19, 35.2%). Of the subtopics for social/environmental context, the investigators identified the most content on community/neighborhood characteristics (N = 7, 13.0%) and general peer/social networks (N = 8, 14.8%). Slightly fewer articles included content on housing/living arrangements (N = 6, 11.1%) and family experiences (N = 4, 7.4%). The least amount of data was identified for sexual networks (N = 3, 5.6%) and church, religion, or ideology (N = 3, 5.6%).

A modest number of articles contained data on homophobia (N = 9, 16.7%). Of the subtopics for homophobia, six articles (11.1%) included content on homophobic attitudes and six articles (11.1%) included content on sexuality-based discrimination. Only four articles (7.4%) included content on racism. Of the subtopics for racism, one article (1.9%) included content on racist attitudes and three articles (5.6%) included content on race-based discrimination. Even fewer articles included content on stigma (N = 2, 3.7%) and of the subtopics for stigma, one article (1.9%) included content on race-based stigma and two articles (3.7%) included content on sexuality-based stigma (see Table 3).

Discussion

This study aimed to provide an integrative review and content analysis of health literature targeting Black YGBMSM between 1988 and 2013. As the issue of identity would feature prominently in this review, the investigators saw fit to begin the discussion on the basic classification strategies that researchers used to describe the study sample. Specifically, the matter of sexual identity was of particular interest and proved to be somewhat complex. Across articles, researchers used a wide range of different sexual identity labels, many of which were conflated into one (e.g., homosexual/gay). The confluence of multiple identity terms may be problematic, as the meaning and significance of one term may not be interchangeable with another, and may thus be an inaccurate representation of the participants involved in the study. Moreover, the term “homosexual” is considered antiquated and pejorative by many LGBT-identified persons, due in large part to its clinical history as a marker of pathology (Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, 2014; Harper, 2010).

Identity labels that have emerged as popular alternatives to traditional LGBT identity terms, such as pansexual and same gender loving, were not reported in any article in this review. Same gender loving in particular has become increasingly popular among some African Americans, as some report the term “LGBT” to be largely associated with a White-dominated community and sociopolitical sphere (Boykin, 2000). Other identity labels, such as two-spirited and questioning, were used sparingly and in combination with other terms as noted above. Nearly half of the participants were classified as MSM with no other identity term, reflecting a common trend in the academic literature of reducing gay and bisexual men to a set of behaviors in studies on sexual health. Researchers have highlighted the inherent shortcomings of this approach, as such labeling reinforces a dominant heterosexist framework, and ignores the nuances of sexual orientation, expression, and community among LGBT or nonheterosexually identified persons (Young & Meyer, 2005). This review thus highlights a need for consensus and consistency in applying identity labels in future research, as well as the importance of promoting identity-affirming language that is sensitive to the variations in self-labeling preferences among nonheterosexually identified persons.

With regard to the five core content areas, topics related to sexual health emerged as the most prominent concern among the population of focus. Nearly every article in this review addressed some aspect of sexual behavior and related health outcomes, most notably HIV, condom use, and sexual activity. The HIV status of study participants was the most frequently addressed HIV subtopic in this review, which may indeed be reflective of the deepening concerns over increasing rates of HIV infection among Black YGBMSM. In contrast, HIV stigma was only explored in two articles, even though many researchers have suggested that stigma related to HIV may be a fundamental driving force behind the epidemic (Maulsby et al., 2014; Smit et al., 2012). Last, HIV treatment knowledge/awareness, linkage/retention in care, and ART use/viral loads/CD4 counts were all poorly represented in this review. Researchers have stressed the universal importance of addressing these topics in the effort to combat HIV, as they have major implications for HIV transmission, treatment, and prevention (World Health Organization, 2012). The findings from this review thus present an opportunity for researchers to address important gaps in the literature on HIV risk and the course of HIV infection among Black YGBMSM.

Many important general sexual health subtopics were seldom addressed across the articles in this review, including experiences of sexual violence, which only appeared in two articles. The association between HIV risk and experiences of violence within same-sex intimate partnerships has received little attention in the scientific literature, and few studies have explored the prevalence of sexual assault and intimate partner violence among LGBT adolescents in general (Freedner, Freed, Yang, & Austin, 2002; Halpern, Young, Waller, Martin, & Kupper, 2004; Heintz & Melendez, 2006). The two articles in the review that captured data on sexual violence did not provide in-depth analyses on the topic, but did note that 20% to 30% of study participants had experienced at least one instance of forced sex or sexual violence (Garofalo, Mustanski, Johnson, & Emerson, 2010; Koblin et al., 2000). Sexual assault and intimate partner violence are both vitally important concerns with serious consequences for the health and well-being of survivors. Given the scarcity of research on this topic for LGBT youth—and especially among Black YGBMSM—future studies that explore issues related to dating, sex, and relationships among Black YGBMSM should pay closer attention to participants’ experiences with sexual violence.

The age of participants’ partners was another topic that only a few articles addressed. Findings from these studies built on a small literature base exploring how romantic/sexual dyads among YGBMSM and older male partners may place YGBMSM at greater risk for HIV infection (Berry, Raymond, & McFarland, 2007; Clerkin et al., 2011; Hurt et al., 2012; Mustanski & Newcomb, 2013). Online partner seeking was also addressed sparingly, though this area of study for GBMSM is relatively new. Researchers reported that online partner seeking was common among Black YGBMSM, and also identified opportunities to pursue sexual health promotion initiatives through mobile phones and online social/sexual networking sites (Fields et al., 2006; George et al., 2012; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2012; Muessig et al., 2013). Both of these topics will have important implications in the development of culturally tailored interventions targeting Black YGBMSM and will be critical for researchers to continue investigating in greater depth.

Sexual positioning was the most commonly occurring general sexual health subtopic in this review. Researchers mostly provided descriptive statistics around participants having receptive or insertive anal sex, with some studies noting differences across racial/ethnic groups. In one study, researchers reported that Latino participants were significantly more likely to have engaged in receptive anal sex when compared with Black participants; in another, researchers noted that Black participants were more likely than White participants to have engaged in receptive anal sex in their most recent sexual encounter with a causal partner (Halkitis et al., 2011; Warren et al., 2007). The distinction between casual versus primary partners (i.e., relationship type) was also frequently referenced across articles, with a wide range of unique findings. One qualitative study highlighted participants’ perceived difficulty of maintaining a long-term relationship in a homophobic society, while another study reported that Black YGBMSM were less likely to have casual partners than other racial/ethnic groups (Harawa et al., 2004; Kubicek, Beyer, Weiss, & Kipke, 2012). The diversity of findings on sexual positioning and relationship type, as well as the implications of these findings for sexual health risk and well-being, suggests that continued research is needed on these important topics. The literature base may be further improved by the inclusion of studies with a dominant focus on relationships and dating, and that explore the negotiation and navigation of these processes, as such topics have received less attention in the literature on Black YGBMSM.

Along with research on sexual health and HIV, sexual orientation identity was also prominently featured in this review and accounted for nearly a third of all psychosocial functioning content codes. This finding gives further credence that sexuality and sexual expression remain the dominant focus of research addressing the health and well-being of Black YGBMSM. Gender expression/identity, in contrast, was rarely discussed, with only four articles collecting data on this topic. Racial/ethnic identity was also underrepresented in the review with only six articles collecting data specific to participants’ experiences as Black men. Of the articles that explored both sexual and racial/ethnic identity together, important distinctions emerged, such as the salience of (a) determining a suitable sexual identity label, (b) exploring cultural heritage, (c) managing stigma around sexual orientation in Black communities and families, and (d) reconciling a host of dual-minority stressors (Balaji et al., 2012; Jamil et al., 2009; Voisin, Bird, Shiu, & Krieger, 2013). While studies that explore identity are inherently meaningful for a population that is oppressed on the basis of identity, it is equally important to acknowledge intersecting identities, as well as the different dimensions of health and experiences that make up the diverse lives of Black YGBMSM. The lack of an intersectional approach to exploring identity reflects an area of great opportunity for researchers, as intersectionality provides a theoretical framework that is inherently suitable for research examining multiple axes of oppression for marginalized groups (Bowleg, 2012). Such an approach may enhance the knowledge of the unique developmental trajectories of Black YGBMSM, and may inform directions for future research and tailored health promotion initiatives for this population.

In terms of other psychosocial functioning issues covered in this review, social support was modestly represented, with 10 articles reporting data on the topic. Both health-promoting and health-harming outcomes related to social support were explored across articles. For example, in one study, researchers reported that Black YGBMSM who scored higher on social support were significantly more likely to have ever been tested for HIV (Mashburn, Peterson, Bakeman, Miller, & Clark, 2004). In a small qualitative study, men who identified as being on the “down-low” spoke of the difficulties related to social isolation and a lack of social support (Martinez & Hosek, 2005). Issues related to social support among Black YGBMSM will be an essential area for investigators concerned with psychosocial functioning and well-being to continue to explore. Researchers may want to consider the social contexts of Black YGBMSM on future studies that address social support, paying particular attention to situations that deny or limit opportunities to secure support from friends, family, or community members.

In addition to social support, depression was also modestly represented in the review, having been discussed across 10 different articles. Many researchers reported that high rates of depressive symptomology was common among this population (Hightow-Weidman, Phillips, et al., 2011; Magnus, Jones, et al., 2010; Wohl et al., 2011). Although a modest number of articles addressed depressive symptomology, only four articles addressed the issue of suicide, and two articles addressed the issues of bullying/harassment and abuse. Both academia and popular media have been filled with passionate discourse around these topics—owing in large part to the increased media coverage of suicides among LGBT youth, which were often a result of bullying and harassment (Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Henkin, 2012). However, there is a considerable gap in the scientific literature investigating these important themes among Black YGBMSM. All four articles in this review that discussed suicide drew data from predominantly Black and Latino samples, and each of them noted that participants reported high rates of ever having made a plan to attempt suicide or ever having made an actual suicide attempt (Hightow-Weidman, Jones, et al., 2011; Hightow-Weidman, Phillips, et al., 2011; Hightow-Weidman, Smith, Valera, Matthews, & Lyons, 2011; Outlaw et al., 2011). Three of these articles, however, used the same data set, in effect leaving only two unique samples from which data were collected that addressed suicide. Overall, this review indicates that there is a paucity of research that addresses psychosocial functioning among Black YGBMSM, as well as critical mortality outcomes such as suicide. Given the severe nature of these topics and the high rates of negative health outcomes reported, researchers should examine these issues in future studies on Black YGBMSM health.

While many of the articles in the review included content on substance use, the majority of these articles included data on the use of drugs other than alcohol or tobacco. Many articles also included “other drugs” in their analyses without further specification about the type of substances involved, though most articles that collected data on substances implicated them as a correlate for HIV risk. There is already an abundance of literature demonstrating that specific types of drugs, such as methamphetamine, have a strong association with HIV risk and are used among some segments of the gay community (Halkitis & Parsons, 2003; Nanín & Parsons, 2006). This review suggests that the health literature targeting Black YGBMSM reflects an enduring concern about the association between drug use and HIV risk for gay men as a whole. It will be important for researchers to continue to monitor these associations, and for public health practitioners to address substance use when designing and implementing interventions for this population.

Although alcohol use was adequately represented in this review, there was a diverse range of findings and discussion on the use of alcohol across articles. In a study investigating clinical samples of HIV-positive young men of color who have sex with men, researchers reported that men with a CD4 count ≤350 who had not started ART were significantly more likely to have consumed alcohol in the past 2 weeks than participants who had started ART (Hightow-Weidman, Jones, et al., 2011). In a 2008 study, researchers reported that Black YGBMSM were significantly more likely to have engaged in sexual activity because of alcohol, and investigators also noted that Black YGBMSM were less likely to binge drink than White YGBMSM (Garofalo et al., 2010; Warren et al., 2007). No article in the review included any discussion on alcohol use outside of the context of HIV risk. Beyond these results, few researchers reported important findings related to alcohol use among Black YGBMSM or differences in its use across race/ethnicity; those who did noted that these differences were marginal and/or did not achieve statistical significance. Given such varied results, the association of alcohol use on health behaviors and outcomes warrants closer attention in future studies on Black YGBMSM.

Content on tobacco use was poorly represented in the review as no article meeting the inclusion criteria included data on this topic. There is a vast literature documenting the ill effects of cigarette and tobacco use among adolescents and adults alike, and researchers have also reported that African American males experience disparate rates of negative health outcomes related to cigarette use when compared with Whites (Chassin, Presson, Sherman, & Edwards, 1990; Gardiner, 2004). The findings from this review thus indicate that there is a considerable lack of research focusing on tobacco use among Black YGBMSM. Researchers with a primary focus in health disparities related to cigarette and tobacco use may consider developing studies that target this population specifically.

Content on substance abuse was also poorly represented in the review. The deficit of data included on substance abuse may be an extension of the overall shortage of data on psychosocial functioning, as the rates of comorbidity between substance abuse and a number of clinical outcomes—including depression and suicide—has been well established (Merikangas et al., 2010; Swendsen et al., 2010). Researchers may consider developing studies that focus on clinical samples of Black YGBMSM who are actively participating in treatment for addiction to better capture data on substance abuse and dependence that may otherwise be elusive in samples drawn from the general population.

This review suggests that studies on health service delivery and receipt, as well as health insurance, are underdeveloped in the literature targeting Black YGBMSM. From the articles collected, the results from studies on the quality and accessibility of health care appear to be mixed. In one study, researchers reported that Black YGBMSM were more likely to receive prevention and counseling services from their providers as well as report greater use of and satisfaction with their health care providers (Behel et al., 2008). Other studies, however, reported that some Black YGBMSM experience difficulties in trusting providers and perceive a lack of respect on the part of providers (Magnus, Jones, et al., 2010; Mashburn et al., 2004). Given the recent changes surrounding accessibility to health insurance through the Affordable Care Act, and the subsequent opportunities to enhance public health prevention efforts, these factors may be of growing significance to both researchers and practitioners (Koh & Sebelius, 2010). This is especially important given the shifting landscape of biomedical treatment and prevention options for HIV. Specifically, the increasing advocacy for making pre-exposure prophylaxis available to sexually active gay men may draw issues related to health insurance and service delivery to the forefront, in addition to the existing needs of those already living with HIV (Underhill, Operario, Mimiaga, Skeer, & Mayer, 2010). Moreover, health insurance and service delivery will remain essential areas of concern for Black YGBMSM seeking psychological services and/or medical care for other health issues. Therefore, the investigators consider it essential for researchers to take these factors into account when developing future studies that address health care for Black YGBMSM.

The final content area in this review examined Black YGBMSM’s experiences in a broader structural context. Of these sociostructural factors, social and environmental context was the most commonly occurring topic, with 19 articles collecting data on a diverse range of subtopics within this area. Each subtopic, however, was only mentioned in a small number of articles with community/neighborhood characteristics, general peer/social networks, and family experiences accounting for the most codes. Issues related to experiences of violence in neighborhoods, social network configurations, and stigma among YGBMSM were also explored in a small number of articles (LaSalaa & Friersonb, 2012; Magnus, Jones, et al., 2010; Martinez & Hosek, 2005; Peterson, Rothenberg, Kraft, Beeker, & Trotter, 2009; Voisin et al., 2013). Despite the fact that stigma was measured as a stand-alone variable in only two articles, discussions across the studies in this review highlighted the pervasiveness of stigma on the basis of sexual behavior or orientation within different social settings. Only three articles included content on church/religion and ideology, yet all of these articles spoke to the inherent challenges associated with sexuality and religion. Researchers have long demonstrated that health promotion initiatives through the Black church can be an effective way to engage community members at risk for adverse health outcomes (Blank, Mahmod, Fox, & Guterbock, 2002; Campbell et al., 2007; Markens, Fox, Taub, & Gilbert, 2002; Thomas, Quinn, Billingsley, & Caldwell, 1994). Researchers may thus consider exploring both the challenges and opportunities associated with the Black church and health outcomes for Black YGBMSM.

In addition to the deficit of literature on religion and church experiences, no study in this review recruited participants through schools, and only three articles included any meaningful discussion on participants’ experiences in a school setting (Edwards, 1996; Stevens, Bernadini, & Jemmott, 2013; Voisin et al., 2013). This is a major shortcoming in the literature, given that researchers have noted that school contexts play an important role in adolescents’ health and risk behaviors (Resnick et al., 1997). The absence of school-based recruitment may limit researchers’ abilities to explore schools as a sociostructural factor, therefore it will be difficult for investigators to fill gaps in the literature addressing this variable. Researchers should thus aim to pursue school-based recruitment strategies as well as examine community, peer, and family contextual factors in future studies on Black YGBMSM health.

Notably, racism and homophobia were not well represented in this review as very few articles collected data on participants’ experiences of race-based or sexuality-based discrimination. This represents yet another gap in the literature addressing Black YGBMSM as these are two fundamental health determinants that may give rise to a range of health disparities (Almeida, Johnson, Corliss, Molnar, & Azrael, 2009; Maulsby et al., 2014; Mays et al., 2007; Williams, 1999). In addition, few articles included data on sexual networks, which is another noteworthy shortcoming in the literature. Researchers continue to gather evidence that implicates sexual network restrictions as a contributor to the proliferation of HIV among Black GBMSM. These restrictions may be partially governed by social determinants of health, such as racial prejudice, or may be a function of selective in-group race preferences (Berry et al., 2007; Clerkin et al., 2011; Raymond & McFarland, 2009). Relatedly, few researchers captured data on the “race of partners” general sexual health subtopic, which further accentuates the gap in the literature on race-related factors and sexual health. Taken together, these findings reflect a gross underrepresentation of the role of race and the social/relational dynamics associated with sexual health risk among Black YGBMSM. Future studies should therefore investigate the ways in which race and racism are associated with the health outcomes of Black YGBMSM, paying special attention to how other contextual variables—such as social networks, communities, and broader social structures—are also associated with health.

Future Research, Limitations, and Strengths

Overall, this review of the literature reveals an exceedingly sparse number of articles addressing Black YGBMSM health between 1988 and 2013. At a total of 54 articles, an approximate average of two articles per year during this time span have been published that meet the criteria for this review. Few articles, however, were published before 2004, illustrating that this population has only garnered the attention of health-focused researchers in recent years. There is ample opportunity, and indeed an ethical imperative, to build a scientific literature base that captures the experiences of a population that has been largely neglected and without voice. To this end, the literature may benefit from the inclusion of well-designed qualitative studies as qualitative research presents an opportunity to communicate the unique and nuanced experiences of a population in ways that quantitative research is less equipped to provide (Clarke, 2004; Johnson & Waterfield, 2004). Only a quarter of the articles in this review included any qualitative component to their research design and analysis, further highlighting that this methodological approach would enhance the scientific community’s understanding of the unique health concerns of Black YGBMSM.

What is perhaps most striking about this review is that, in spite of an overall paucity of research on this population, the overwhelming majority of research that does exist is centered on sex—to the neglect of other critical health domains. For example, there were considerably more articles represented among the sexual health content area when compared with the psychosocial functioning content area. Moreover, sexual orientation identity accounted for nearly half of all the psychosocial functioning content codes, demonstrating that even within this content area, sexuality is still placed at the forefront. It is difficult to determine the precise reasons for why other content areas are so underresearched when compared with sex, though it is reasonable to assume that the overemphasis on sexuality and sexual health is reflective of epidemiologic trends of disproportionate HIV and STI risk among Black YGBMSM. While these trends demand the attention of researchers and practitioners, it is important to keep in mind that Black YGBMSM have multifaceted health concerns. Researchers should be cautious about how the overall needs and characteristics of this population are reflected through the topics that are most often explored—as well as those that are often overlooked. The current state of health literature may give the impression that sex and sexuality are the most salient dimensions of Black YGBMSM experiences and the most central health priorities for this population. In turn, Black YGBMSM may become inadvertently reduced to their sexualities, which not only provides limited insights into this population but is also potentially stigmatizing. Moving forward, it will be important for researchers to augment the dominant health discourses around Black YGBMSM with studies that examine the varied and complex health needs of this population.

As the methodological strategy for this study employs an integrative and content analytic review process, there are a few limitations to note about this particular approach. The integrative review has faced criticism due to potential concerns around researcher bias, amassing incomplete data, and an overall lack of rigor in the review process (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). The investigators have attempted to address these concerns by (a) having a clearly defined population of focus, (b) identifying a specific set of predetermined health content areas and demographic characteristics to be examined, (c) including a consistent and systematic search method in scholarly databases, and (d) providing clear criteria for inclusion/exclusion of articles. Content analysis is also limited by its purely descriptive nature and its inability to answer important phenomenological questions. The investigators acknowledge this limitation, and attempt to draw inferences about the findings to the extent that is possible, while offering suggested avenues for future research.

Another limitation of this study involves potential concerns with measurement of constructs. The investigators did not, for example, scrutinize the instruments used to measure social support—though these self-report inventories varied across studies, with a number of researchers using questions developed in-house or including items that were tailored to specific topics (e.g., social support around issues related to sex). In addition, the study population in this review is restricted to U.S.-based samples. The literature detailing the experiences of Black YGBMSM in other countries may provide a meaningful supplement to the research based in the United States, and would also allow the investigators to speak to a broad range of health concerns among this population. It was determined, however, that inclusion of these studies would be beyond the scope of this review, especially given the importance of evaluating health issues within specific sociopolitical and cultural contexts. Last, given space limitations, discussion on specific topics that did not fall into the predetermined content areas and subtopic codes were omitted. For example—variables such as geographic region, perceived risk of becoming infected with HIV, infidelity, romantic loneliness, and many others—occurred infrequently and were highly specific, and were thus coded as “other” in their respective content areas. Future studies may benefit from the inclusion of these variables to enhance current understandings of their association with health outcomes for Black YGBMSM.

This study is strengthened by its examination of a broad range of health issues for the target population, and is among the first to review and consolidate such an extensive scope of health research on Black YGBMSM. Another strength of this study includes the concentrated yet flexible demographic inclusion criteria. The restriction of articles on the basis of race and race-specific analyses enabled the investigators to capture data that reliably examine Black YGBMSM, but it also allowed them to include racially diverse articles that contained equally meaningful findings about this population. Last, the systematic approach in both the review and coding process allowed the investigators to organize the study to obtain the most relevant content and present an accurate, comprehensive overview of the literature. Overall, the investigators hope that this review brings important health topics that have been neglected in the literature to the forefront of public health discourse surrounding Black YGBMSM. The investigators hope that these findings serve as a platform to guide new research and inform health promotion initiatives for this highly marginalized population.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education at the University of Michigan, School of Public Health.

References

All articles with an asterisk are a part of the literature review.

- Almeida J., Johnson R. M., Corliss H. L., Molnar B. E., Azrael D. (2009). Emotional distress among LGBT youth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 1001-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Arrington-Sanders R., Leonard L., Brooks D., Celentano D., Ellen J. (2013). Older partner selection in young African-American men who have sex with men. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 682-688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bakeman R., Peterson J. L. (2013). Do beliefs about HIV treatments affect peer norms and risky sexual behavior among African American men who have sex with men? International Journal of STD and AIDS, 18, 105-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Balaji A. B., Oster A. M., Viall A. H., Heffelfinger J. D., Mena L. A., Toledo C. A. (2012). Role flexing: How community, religion, and family shape the experiences of young Black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 26, 730-737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister J. A. (2012). Romantic ideation, partner-seeking, and HIV risk among young gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 431-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Behel S. K., MacKellar D. A., Valleroy L. A., Secura G. M., Bingham T., Celentano D. . . . Young Men’s Survey Study Group. (2008). HIV prevention services received at health care and HIV test providers by young men who have sex with men: An examination of racial disparities. Journal of Urban Health, 8, 727-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D. L., Bauman A. (2000). Adolescent mental health and risky sexual behavior. British Medical Journal, 321(7256), 251-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M., Raymond H., McFarland W. (2007). Same race and older partner selection May explain higher HIV prevalence among black men who have sex with men. AIDS, 21, 2349-2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkett M., Espelage D. L., Koenig B. (2009). LGB and questioning students in schools: The moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 989-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank M. B., Mahmod M., Fox J. C., Guterbock T. (2002). Alternative mental health services: The role of the black church in the south. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 1668-1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1267-1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boykin K. O. (2000). Where rhetoric meets reality: The role of Black lesbians and gays in “queer” politics. In Rimmerman C. A., Wald K. D., Wilcox C. (Eds.), Politics of gay rights (pp. 79-96). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D., Harper G. W. Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2011). Operating without a safety net: Gay male adolescents’ responses to marginalization and migration and implications for theory of syndemic production for health disparities. Health Education & Behavior, 38, 367-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D., Harper G. W., Fernandez M. I., Jamil O. B. Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2012). Age-concordant and age-discordant sexual behavior among gay and bisexual male adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 441-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese S. K., Rosenberger J. G., Schick V. R., Novak D. S., Reece M. (2013). An event-level comparison of risk-related sexual practices between black and other-race men who have sex with men: Condoms, semen, lubricant, and rectal douching. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 27, 77-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. K., Hudson M. A., Resnicow K., Blakeney N., Paxton A., Baskin M. (2007). Church-based health promotion interventions: Evidence and lessons learned. Annual Review of Public Health, 28, 213-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Celentano D. D., Sifakis F., Hylton J., Torian L. V., Guillin V., Koblin B. A. (2005). Race/ethnic differences in HIV prevalence and risks among adolescents and young adult men who have sex with men. Journal of Urban Health, 82, 610-621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. (2011). Rates of diagnoses of HIV infection among adults and adolescents, by area of residence—United States. HIV Surveillance Report, 23, 1-84. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. (2013). HIV testing and risk behaviors among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men—United States. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62, 958-962. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L., Presson C. C., Sherman S. J., Edwards D. A. (1990). The natural history of cigarette smoking: Predicting young-adult smoking outcomes from adolescent smoking patterns. Health Psychology, 9, 701-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke L. (2004). The value of qualitative research. Nursing Standard, 18(52), 41-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Clerkin E. M., Newcomb M. E., Mustanski B. (2011). Unpacking the racial disparity in HIV rates: The effect of race on risky sexual behavior among Black young men who have sex with men (YMSM). Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 34, 237-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Cohall A., Dini S., Nye A., Dye B., Neu N., Hyden C. (2010). HIV testing preferences among young men of color who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 1961-1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Countryman J. (2012). Substance use in adolescents. In Klykylo W. M., Kay J. (Eds.), Clinical child psychology (3rd ed., pp. 243-254). West Sussex, England: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett L. J. (1997). Cultural, historical, and subcultural contexts of adolescence: Implications for health and development. In Schulenberg J., Maggs J. L., Hurrelmann K. (Eds.), Health risks and developmental transitions during adolescence (pp. 23-53). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli A. R. (2002). Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths ages 14 to 21. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7, 433-456. [Google Scholar]

- Deas D. (2005). Adolescent substance abuse and psychiatric comorbidities. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(Suppl. 7), 18-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Dorell C. G., Sutton M. Y., Oster A., Hardnett F., Thomas P. E., Gaul Z. J., . . . Heffelfinger J. D. (2011). Missed opportunities for HIV testing in health care settings among young African American men who have sex with men: Implications for the HIV epidemic. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 25, 657-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim S. H. (2004). Race/ethnic disparities in HIV testing and knowledge about treatment for HIV/AIDS: United States, 2001. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 18, 27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Edwards W. J. (1996). A sociological analysis of an in/visible minority group: Male adolescent homosexuals. Youth & Society, 27, 334-355. [Google Scholar]

- *Eyre S. L., Milbrath C., Peacock B. (2007). Romantic relationship trajectories of African American gay/bisexual adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 107-131. [Google Scholar]

- *Fields E. L., Bogart L. M., Smith K. C., Malebranche D. J., Ellen J., Schuster M. A. (2012). HIV risk and perceptions of masculinity among young Black men who have sex with men. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50, 296-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Fields E. L., Wharton M. J., Marrero A. L., Little A., Pannell K., Morgan J. H. (2006). Internet chat rooms: Connecting with a new generation of young men of color at risk for HIV infection who have sex with other men. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 17(6), 53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Flores S. A., Bakeman R., Millett G. A., Peterson J. L. (2009). HIV risk among bisexually and homosexually active racially diverse young men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 36, 325-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Forney J. C., Miller R. L. (2012). Risk and protective factors related to HIV-risk behavior: A comparison between HIV-positive and HIV-negative young men who have sex with men. AIDS Care, 24, 544-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedner N., Freed L. H., Yang Y. W., Austin S. B. (2002). Dating violence among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: Results from a community survey. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 469-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M. S., Marshal M. P., Stall R., Cheong J., Wright E. R. (2008). Gay-related development, early abuse, and adult health outcomes among gay males. AIDS Behavior, 12, 891-902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner P. S. (2004). The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 6, 55-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Garofalo R., Mustanski B., Johnson A., Emerson E. (2010). Exploring factors that underlie racial/ethnic disparities in HIV risk among young men who have sex with men. Journal of Urban Health, 87, 318-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. (2014). Glossary of terms/language—Terms to avoid. In GLAAD media reference guide (9th ed.). Retrieved from http://www.glaad.org/reference/offensive

- *George S., Phillips R., McDavitt B., Adam W., Mutchler M. G. (2012, November). The cellular generation and a new risk environment: Implications for texting-based sexual health promotion interventions among minority young men who have sex with men. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, Chicago, IL, 247-256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Guenther-Grey C. A., Varnell S., Weiser J. I., Mathy R. M., O’Donnell L., Stueve A. . . . Community Intervention Trial for Youth Study Team. (2005). Trends in sexual risk-taking among urban young men who have sex with men, 1999-2002. Journal of National Medical Association, 97(7 Suppl.), 38-43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A. P., Eliason M., Mays V. M., Mathy R. M., Cochran S. D., D’Augelli A. R., . . . Clayton P. J. (2010). Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(1), 10-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Halkitis P. N., Brockwell S., Siconolfi D. E., Moeller R. W., Sussman R. D., Mourgues P. J., . . . Monica M. (2011). Sexual behavior of adolescent emerging and young adult men who have sex with men ages 13-29 in New York City. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 56, 285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis P. N., Parsons J. T. (2003). Recreational drug use and HIV-risk sexual behavior among men frequenting gay social venues. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 14(4), 19-38. [Google Scholar]

- Hall H. I., Byers R. H., Ling Q., Espinoza L. (2007). Racial/ethnic and age disparities in HIV prevalence and disease progression among men who have sex with men in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1060-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern C. T., Young M. L., Waller M. W., Martin S. L., Kupper L. L. (2004). Prevalence of partner violence in same-sex romantic and sexual relationships in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35, 124-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halverson E. R. (2005). InsideOut: Facilitating gay youth identity development through a performance-based youth organization. American Journal of Public Health, 5, 67-90. [Google Scholar]

- *Hampton M. C., Halkitis P. N., Storholm E. D., Kupprat S. A., Siconolfi D. E., Jones D., . . . McCree D. H. (2013). Sexual risk taking in relation to sexual identification, age, and education in a diverse sample of African American men who have sex with men (MSM) in New York City. AIDS Behavior, 17, 931-938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Harawa N. T., Greenland S., Bingham T. A., Johnson D. F., Cochran S., Cunningham W. E., . . . Valleroy L. A. (2004). Associations of race/ethnicity with HIV prevalence and HIV-related behaviors among young men who have sex with men in 7 urban centers in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 35, 526-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper G. W. (2010). A journey toward liberation: Confronting heterosexism and the oppression of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people. In Nelson G., Prilleltensky I. (Eds.), Community psychology: In pursuit of wellness and liberation (2nd ed., pp. 407-430). London, England: MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Harper G. W., Schneider M. (2003). Oppression and discrimination among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people and communities: A challenge for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 243-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hart T., Peterson J. L. (2004). Predictors of risky sexual behavior among young African American men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 1122-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler M. L. (2011). The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics, 127, 896-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins J. D., Catalano R. F., Miller J. Y. (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychology Bulletin, 112, 64-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintz A. J., Melendez R. M. (2006). Intimate partner violence and HIV/STD risk among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21, 193-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkin R. (2012). Confronting bullying: It really can get better. English Journal, 101(6), 110-113. [Google Scholar]

- *Hightow-Weidman L. B., Hurt C. B., Phillips G., 2nd, Jones K., Magnus M., Giordano T. P. . . . The YMSM of Color SPNS Initiative Study Group. (2011). Transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance among young men of color who have sex with men: A multicenter cohort analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48, 94-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hightow-Weidman L. B., Jones K., Phillips G., 2nd, Wohl A. R., Giordana T. P. (2011). Baseline clinical characteristics, antiretroviral therapy use, and viral load suppression among HIV-positive young men of color who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 25, 9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hightow-Weidman L. B., Jones K., Wohl A. R., Futterman D., Outlaw A., Phillips G., 2nd . . . The YMSM of Color SPNS Initiative Stud Group. (2011). Early linkage and retention in care: Findings from the outreach, linkage, and retention in care initiative among young men of color who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 25, 31-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hightow-Weidman L. B., Phillips G., 2nd, Jones K. C., Outlaw A. Y., Fields S. D., Smith J. C. (2011). Racial and sexual identity-related maltreatment among minority YMSM: Prevalence, perceptions, and the association with emotional distress. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 25, 39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hightow-Weidman L. B., Pike E., Fowler B., Kibe J., McCoy R., Pike E., . . . Adimora A. (2012). HealthMpowerment.org: Feasibility and acceptability of delivering an internet intervention to young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Care, 24, 910-920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hightow-Weidman L. B., Smith J. C., Valera E., Matthews D. D., Lyons P. (2011). Keeping them in “STYLE”: Finding, linking, and retaining young HIV-positive Black and Latino men who have sex with men in care. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 25, 37-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt C. B., Matthews M. M., Stapleton A. A., Adimora C. E., Golin C. E., Hightow-Weidman L. B. (2012). Sex with older partners is associated with primary HIV infection among men who have sex with men in North Carolina. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 54, 185-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Jamil O. B., Harper G. W., Fernandez M. I. (2009). Sexual and ethnic identity development among gay-bisexual-questioning (GBQ) male ethnic minority adolescents. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15, 203-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Johnson A. S., Hu X. J., Sharpe T. T., Dean H. D. (2009). Disparities in HIV/AIDS diagnoses among racial and ethnic minority youth. Journal for Equity in Health, 2, 4-18. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R., Waterfield J. (2004). Making words count: The value of qualitative research. Physiotherapy Research International, 9, 121-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Jones K. T., Johnson W. D., Wheeler D. P., Gray P., Foust E., Gaiter J. (2008). Nonsupportive peer norms and incarceration as HIV risk correlates for young Black men who have sex with men. AIDS Behavior, 12, 41-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K. M. (2000). Substance abuse among gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and questioning adolescents. School Psychology Review, 29, 201-206. [Google Scholar]

- *Koblin B. A., Torian L. V., Guilin V., Ren L., MacKellar D. A., Valleroy L. A. (2000). High prevalence of HIV infection among young men who have sex who have sex with men in New York City. AIDS, 14, 1793-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh H. K., Sebelius K. G. (2010). Promoting prevention through the Affordable Care Act. New England Journal of Medicine, 363, 1296-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw J. G., Greytak E. A., Diaz E. M. (2009). Who, what, where, when, and why: Demographic and ecological factors contributing to hostile school climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 976-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf K. (2013). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- *Kubicek K., Beyer W. J., Weiss G., Kipke M. D. (2012). Photovoice as a tool to adapt an HIV prevention intervention for African American young men who have sex with men. Health Promotion Practice, 13, 535-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *LaSalaa M. C., Friersonb D. T. (2012). African American gay youth and their families: Redefining masculinity, coping with racism, and homophobia. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 8, 428-445. [Google Scholar]