Abstract

This article explores the use of photo-elicitation methods in two men’s health studies. Discussed are the ways that photo-elicitation can facilitate conversation about health issues that might be otherwise challenging to access. In the first study, researchers explored 35 young men’s experiences of grief following the accidental death of a male peer. In the second study, researchers describe 64 fathers’ perceptions about their roles and identity with respect to child safety and risk. Photographs and accompanying narratives were analyzed and results were theorized using a masculinities framework. Discussed are the benefits of photo-elicitation, which include facilitating conversation about emotions, garnering insight into the structures and identities of masculinity in the context of men’s health. Considered also are some methodological challenges amid recommendations for ensuring reflexive practices. Based on the findings it is concluded that photo-elicitation can innovatively advance qualitative research in men’s health.

Keywords: photo-elicitation, research, qualitative, masculinity, bereavement/grief, fathers, fathering

Introduction

Scholarship of Western masculinities, particularly work done in the past two decades, has highlighted the potential for shifts from traditional ideals of manhood, which include stoicism, rationality and instrumentality toward contemporary practices embodied by emotional availability, nurturance, and active engagement within the domestic sphere (Aiken, 2009; Daly, 1993; Levant, 2008). In a variety of spaces, social conventions encourage men to lay claim to contemporary ideals (Levant & Pollack, 2001), but Wall and Arnold (2007) suggest that men’s practices are far more nuanced. They argue that contemporary and traditional values practices merge in complex ways and the notion of a new masculinity, as unbounded from previous embodiments of masculinity, is a cultural trope (Pommper, 2010; Wall & Arnold, 2007). The persistence of traditional ideals is illustrated in the way that men who do not lay claim to traditional ideals of superiority, dominance, and a tough exterior are routinely marginalized within masculine hierarchies (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Courtenay, 2011).

The interplay between contemporary and traditional discourses of masculinity has received limited attention (Levant & Pollack, 2001; Silverstein, Auerbach, & Levant, 2002) and is poorly understood in men’s health research. This is likely because of the fact that, short of using observational methods, it can be challenging for researchers to garner contextual understandings about men’s reference points and the interconnections between masculine identities and men’s health practices. This article reports that photo-elicitation (PE) methods were successfully used in two separate men’s health studies to facilitate the expression and exploration of emotion and enrich conversations on structures and identities of masculinity. Revealed are the ways that PE methods are adapted to advance the collection of context rich data within each of the aforementioned studies to advance understandings of men’s health practices.

Visual Methods

PE is part of a family of visual methods that includes, among others, photovoice (Wang & Burris, 1997), photo interviewing (Hurworth, 2003), and reflexive photography (Berman, 2001), and uses participant-produced photographs as a means to represent participant’s experiences. The primary emphasis of PE is the rich discussion that can occur about the photographs that research participants take in preparation for a qualitative in-depth interview (Clark-IbáÑez, 2007; Drew, Duncan, & Sawyer, 2010; Keller, Fleury, Perez, Ainsworth, & Vaughan, 2008; Oliffe & Bottorff, 2007; Packard, 2008). Photographs can then be used as reference points with which participants can guide the researcher through their story at their own speed (Clark-IbáÑez, 2004). A record is kept of the narration and both the photos and the interview transcript contribute data that are subsequently analyzed (Allen, 2009; Author, 2007).

While semistructured verbal interviews are the most common form of qualitative data collection, adding a visual dimension into the research process, such as PE, has grown in popularity (Catalani & Minkler, 2010). This is due to the recognition that the use of visual methods can help researchers to obtain nuanced insights that might not emerge through verbal accounts alone. PE fosters sharing rather than telling a story in the interview context facilitating unique researcher–participant connections (Allen, 2008). Though researchers and participants may inhabit diverse social and cultural worlds, photographs can be windows into the daily realities, places, and spaces occupied by participants (Clark-IbáÑez, 2007). The content within the photographs can be as concrete or symbolic as the participant chooses, allowing for an exploration of the phenomenon in metaphorical or literal terms (Creighton, 2011).

Men, Health Research, and Visual Methods

In their recent article, Affleck, Glass, and Macdonald (2013) argue that men’s experiences related to issues involving emotional complexity are underrepresented in qualitative health research. Affleck et al. along with other authors including Oliffe and Mroz (2005), Schwalbe and Wolkomir (2001) and Addis and Mahalik (2003), suggest that men are challenged to articulate their emotional experiences. Qualitative research that relies on an ability to spontaneously access, reflect on, and then communicate these experiences can be at odds with dominant ideals of masculinity within which men are expected to be expert and seek dominance (Affleck et al., 2013; Schwalbe & Wolkomir, 2001). PE methods afford a number of benefits when doing research with men that can help to overcome some of the identified challenges, which include providing an opportunity to build rapport, offering participants greater control in directing the interview process, allowing for time for reflection on the topic prior to the interview, and providing therapeutic experience for participants (Affleck et al., 2013; Oliffe & Bottorff, 2007; Oliffe & Mroz, 2005).

Another affordance of PE methods, particularly relevant to men’s health research, is the way it can facilitate the exploration of men’s conflicting identities between contemporary and traditional ideals of masculinity. Using semistructured interviews alone can pressure men to bring coherence to their identity, which can obscure the nuance in identity construction that transpires as men move through different places and social spaces (Butler, 2004; Connell, 2005; Elliott, 2005; Kohon & Carder, 2014). Referring to autophotographic methods, Kohon and Carder (2014) articulate that “participants create visual representations of their identity that add additional layers of meaning to qualitative research” (p. 49). Data that reflect the often conflictual process of identity construction can provide rich insights into men’s health practices.

The ways in which photographic methods can be used to effectively garner reflection on the array of masculine ideals was illustrated in our own work. For instance, similar studies were conducted on men and fathering—the first using qualitative interviews and the second augmenting that approach with PE methods. The first study (Brussoni & Olsen, 2011) elicited views and perspectives on what fathers do in relation to children’s play and why they do it. The second study (described in the current article) produced richer accounts chronicling more fully the fathers’ identities and how culture, community conventions, and personal experiences connected in the construct of fathering as a masculine practice (Creighton, Brussoni, Oliffe & Olsen, 2015). The addition of photographs allowed participants and researchers to explore the layers and nuances of the fathering role, where identity and practices converge and diverge.

The aim of the current article is to build on previous work on the PE methodological approach by sharing these two empirical examples in which PE methods provided unique insights about masculinities and health. Detailed is the utility of these methods, highlighting the potential for PE methods to facilitate conversation about emotions and explore, with participants, the structures and identities of masculinity to enrich men’s health research. The first study, Guys and Grief, was conducted with men who had lost a male friend to accidental death, with a focus on participants’ gendered experiences and expressions of grief. In the second project, the Canadian Fathers Study (CFS), we explored the way that fathers think about risk and safety for their young children, and their reflections on the father/child relationship. While the focus of the current article is to discuss the PE-related findings that have emerged from these two studies, a more expanded description of each study and the empirical findings can be found elsewhere see Creighton & Oliffe, 2010; Brussoni, Creighton, Olsen & Oliffe, 2013; Creighton, Oliffe, Matthews & Saewyc, 2015; Creighton, Brussoni, Oliffe, Olsen, 2015.

Project 1: Guys and Grief

Injuries are the leading cause of death for men aged 15 to 30 years (Statistics Canada, 2012). Little is known about the health outcomes for young men, who may in a period of their life be less attached to family and community institutions amid grieving the loss of a male peer. Connell’s (1995) hegemonic and multiple masculinities framework informed our study of young men’s grief processes and practices following the death of a male friend. Explored were the ways that men constructed gendered identities across time and space, and actively not only sustain but also contest masculine ideals about what it is to be a man in the aftermath of such a loss. Also incorporated was a Communities of Practice framework (Paechter, 2003) to discern and describe how masculine identities are embodied and normed within specific milieus and locales in the context of losing a male peer.

Method

Participants

Thirty-five men, aged 19 to 25 years (mean = 21) who had experienced the death of a male friend within the past 3 years, participated in the study. Participants resided in metro Vancouver and the mountain resort of Whistler, British Columbia. Interviews were conducted in 2010-2011 by two female researchers with training in qualitative interviewing and PE methods. Participants were provided with a digital camera and received a $20 honorarium to acknowledge their contribution to the project.

Following University ethics approval, participants were recruited using posters, flyers, online advertising (Facebook and Craigslist), and word of mouth. Information regarding the project and its aims were distributed to staff of local youth serving organizations so that they could both post information and direct study information to potential participants. Participants could request more information or volunteer for the study by contacting researchers by telephone, text, or e-mail using the contact information provided on the recruitment materials. Initial conversations with volunteers were used to evaluate eligibility and subsequently explain the goals of the research. Recruitment and interviewing continued until the repetition of themes and story elements indicated that data saturation was reached.

Data Collection

Two individual interviews were conducted 1 month to 2 years following the death of a male friend. The first interview served as an opportunity to obtain written consent, collect demographic information, and hear the story of the friend’s death and surrounding circumstances. Following this interview, participants were given 2 weeks to take photographs to chronicle their experiences of losing a male peer. The second in-depth, semistructured interview was driven by the photographs that participants had taken, highlighting the men’s experiences of grief. The participants brought their camera to the second meeting and photographs were loaded onto a laptop computer for viewing in the interview. The photographs were reviewed individually with the researcher inquiring into the reasons the participant had for taking the photo and the meanings that he made from it. All photographs taken by participants were included in the interview. Photographs were discussed in the order outlined by the photo assignment which followed the set of themes proposed by the researcher (Table 1).

Table 1.

Photo Instructions for Guys and Grief Study.

| This is like a questionnaire that you answer with a photograph instead of with words. Remember, there are no wrong or right answers. |

| 1. Where did you and your friend hang out? |

| 2. What did you and your friend do together? |

| 3. After your friend died, what did you do and where did you go? |

| 4. What places remind you of your friend? |

| 5. What do you do to honor your friend? |

| 6. Take a picture of something that represents how you felt after your friend died |

| 7. What symbolizes being a man to you? |

| 8. What do you think symbolizes being a man to your friends? |

| 9. What does it mean when people say “man up”? |

| 10. What is one thing you can’t say? |

Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim with pseudonyms given to participants to maintain anonymity. Photographs were downloaded into a password-protected file from the camera’s memory card which was subsequently erased. The 402 participant photographs were embedded in the interview transcripts and organized using qualitative data analysis software (Atlas.ti6).

Data Analysis

Textual and photographic data were analyzed by the first and third author. While there are multiple strategies for analyzing textual and photo data, this study used the most common approach, using constant comparison and grounded theory methods (Charmaz, 2006; Dey, 1999). Open coding was used to develop conceptual labels for discrete events or phenomenon identified in the data. Using constant comparative techniques first-level codes into broader categories were grouped and condensed, using axial coding to make connections between categories and subcategories. This coding process provided a frame for analysis and facilitated a reassembling of data that were fractured during the initial coding procedures. Selective coding was used to integrate the larger, encompassing categories.

Following analysis of text and photographs together, photographs were analyzed using a three-stage process described by Oliffe, Bottorff, Kelly, and Halpin (2008) and informed by the work of Dowdall and Golden (1989). In the first stage, the photograph was viewed alongside the participant’s narrative to gain insight into the ways men understood and viewed their images. In a second stage of analysis, the photograph was considered from the perspective of the researcher. Carefully reviewed by the researchers were details in the images and who was depicted in the photographs while reflecting on cultural practices and contexts. Discussed were the ways that our own experiences and identities might influence the lens with which we viewed the photos. These processes were used to contextualize participant’s accounts, challenge assumptions, and integrate participant and researcher interpretations. In a third stage, all the photographs were laid out to discern overall themes and interpretations. In the first stage, the photograph was viewed alongside the participant’s narrative in order to gain insight into the ways men understood and viewed their images. In the second stage of analysis, the photograph was considered from the perspective of the researcher. We carefully reviewed the details in the images including who was depicted in the photographs while reflecting on cultural practices and contexts. We noted the ways in which reflections on the photographs were similar to or diverged from those of participants; and the team discussed how their own experiences and identities might influence the lens with which the photos were interpreted. These processes were used to contextualize participant’s accounts, challenge assumptions, and integrate participant and researcher interpretations. In the third stage, all the photographs were laid out to discern overall themes and interpretations. At this stage of analysis, Connell’s (1995) and Connell and Messerschmidt’s (2005) model of hegemonic masculinities were considered to think about narratives of identity. Through examining the ways that extracted themes aligned with and contested traditional and contemporary masculine ideals, photographs and emergent findings were theorized. The process of analysis was continually informed by insights from both the qualitative interview transcripts and the photographs, weaving together both sets of data to discern results.

Adapting the Approach

To balance direction and creativity, participants were given a “photo assignment.” Participants were instructed to view the photo assignment as a questionnaire, a familiar structure to most that they would answer with pictures instead of words. The photo assignment, informed by masculinities and community of practice frameworks (Connell, 1995; Paechter, 2003), focused on gendered embodiments, practices, and performances in the context of losing a male peer to an accidental death. Participants were asked to represent the social contexts of the friendship, how they experienced grief over the loss, and the ways sought to memorialize the friend, along with reflecting on the potential tensions round grieving in acceptable “manly” ways. The photo assignment was adjusted slightly, following initial interviews, to be more specific regarding images of masculinity. We recognized that our question “What does it mean to be a man?” was disembodied, and therefore it was difficult for participants to produce a photograph that was not a simple stereotype. For this reason, we embodied the photo assignment to ask, two questions “What does it mean to be a man to you?” and “What does it mean to be a man to your friends?”

In order to avoid influencing the type of photographs taken, the researcher did not give other instructions to the participant. When given the opportunity to ask questions, the participants typically asked about the number of photographs that they were expected to take, to which the researcher replied that there was no set limit.

Results

Highlighted in this section are the ways that the PE approach was useful to promote discussion about participants’ masculinities in the context of their grief, and how the use of PE enriched conversations about the emotional experience of losing a friend. All names included in the results are pseudonyms.

One of the primary aims in this study was to elicit men’s descriptions of grief in a social context in which ideals of masculinity exclude performances of vulnerability and expressions of sadness. To this end, participants were asked to produce photographs that showed the way that they sustained and/or contested masculine identities following the loss of a male friend. As anticipated, most participants struggled to produce images of masculinities. Many men grappled between their impulse to take pictures that symbolized what they believed to be society’s ideals and discerning an image that symbolized their own gendered identity. Most participants resolved this issue by producing images that they saw as social stereotypes of manhood, including “getting girls” and “having cool cars,” and then issuing their own critique.

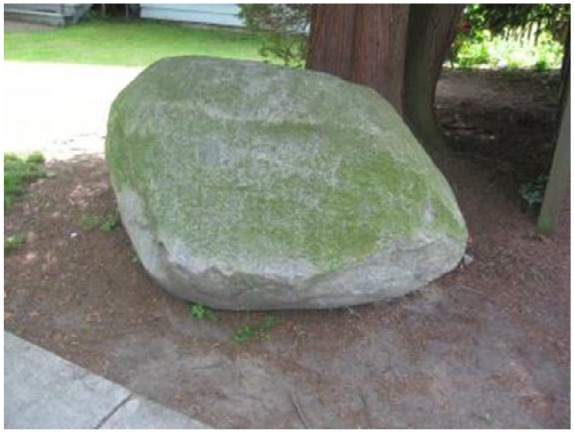

Joe’s photograph (Figure 1), exemplifies this reflexive understanding of masculinity. He was 19 when his friend fell through a skylight at a party. Now aged 22 years, Joe described a stereotyped masculinity: “Kind of like that caveman image [roars for emphasis] who just comes out ready to fight or run or kill, without thought or consideration for what he is doing.” He explained that this masculinity could be symbolized by his photo of the boulder (Figure 1): “This big rock, it’s like strong and immovable but kind of standing alone and not supported by anything.”

Figure 1.

Masculinitiy as a Boulder.

Joe argued that this embodiment of masculinity was wrongheaded, stating that it is better to “work together.” He, like many other participants, maintained that this sturdy oak, overly armored performance of masculinity was one that the intelligent, evolved man should strive to rise above rather than aspire to. He stated, “You’ve got to get beyond, you know, that kind of overly guy that is such a big deal in high school, You need to move on.”

While the majority of participants rejected stereotyped versions of hypermasculinity, photos, and narratives emerging from the “Take a picture of something that represents how you felt after your friend died” elucidated the ways that participants found it challenging to reconfigure dominant configurations of masculine practices (Schippers, 2007). In other words, even though participants were critical of some aspects of dominant masculinity, these representations emerged as central to their own grief processes. In response to the photo prompt, for example, the strongest themes were of feeling hollow, empty, and removed. Participants spoke about feeling as though they were standing outside and dissociated from the world, unable to connect with friends or family.

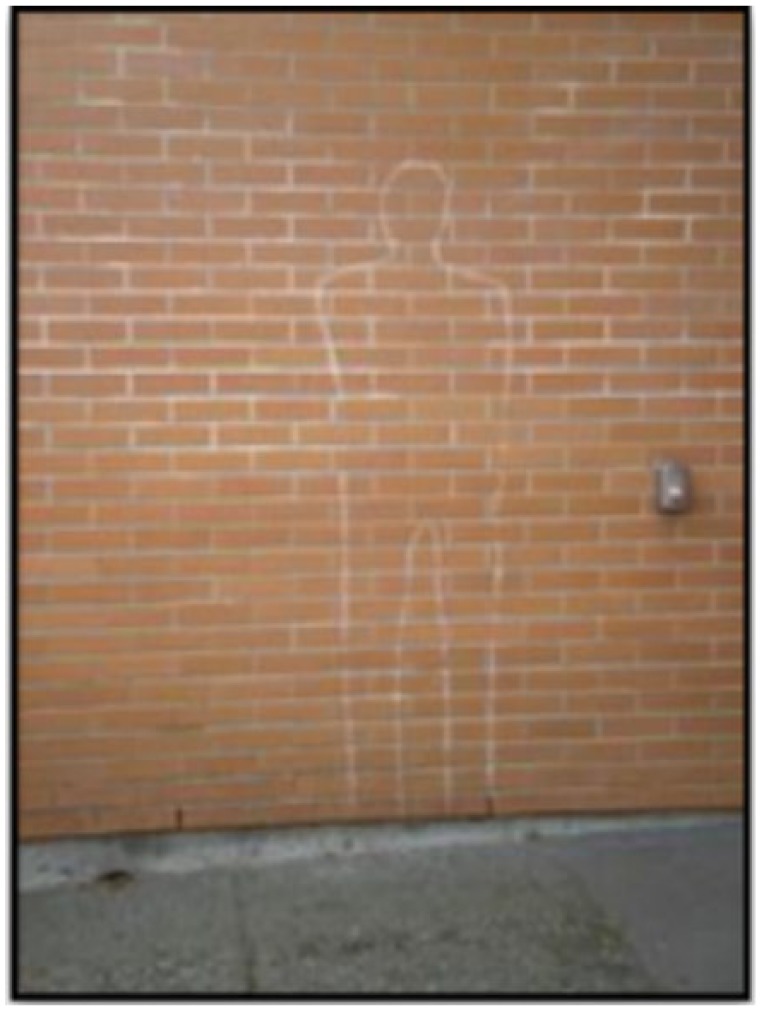

When Jim was 20 years old, his childhood friend died in a scooter accident while driving home from a bar. When Jim received the call from his parents with the news, he felt as though he was walking around like a “hollow man” (Figure 2): “Do you see that chalk outline of a person on the wall? It’s just outside the library and I only just noticed it. That’s how I felt. Hollow, like a person could just walk by.”

Figure 2.

Invisable Man.

While dismissing the disaffected, invulnerable masculinity as “shallow,” Jim’s own experience of grieving the death was not only one of being disconnected but also wanting disconnection from others. The image of a brick wall reflected his impenetrability, consistent with his narrative of backing away from family and friends who tried to “help.” By embodying a hollow man identity he was able to internalize the grief experience maintaining invisibility synonymous with the cool rationality of the masculinity he critiqued.

Chris, a 21-year-old, had a friend passed away following a drug overdose. His picture, a plain brick wall, portrayed the ways in which he experienced grief at the memorial for his friend (Figure 3):

I thought I would cry. Maybe somewhere deep down I wanted to, but maybe not. This wall is like me, sort of solid and strong, you know. I was the one that people—usually girls—could lean on . . . or against in the way that this picture represents.

Figure 3.

Impenetrable Brick Wall.

Chris described his restraint, weighing the possibility that he might have wanted to break down but opted not to. In not crying or being visibly vulnerable he could be the pillar of strength and support for those less resilient—women. In this account, Chris’s strength is mobilized to protect and console others offering the dual positioning of aligning to masculine ideals while understanding but resisting feminine expressions and the need for support.

Markus, a 25-year-old whose friend was killed when he drove his car off an embankment, also produced an image of concrete (Figure 4) to symbolize his grief over the death. He likened the shock of hearing about his friend’s passing to having an object larger and harder than his strong façade come at him without warning, producing irreparable damage in the wake of such tragic events: “When I found out about P’s death I just felt like there were all of these cracks in me. Like, I would not be the same person. That’s why I took a picture of this concrete.”

Figure 4.

Cracks in the Concrete.

In contrast to Jim’s and Chris’s photographs, Markus’s image and narrative conceded that grief catalyzed him toward reformulating performances of masculinity. Marcus likened the grass growing through the cracks in the concrete as new life and transformation. Rather than hardening him and bolstering his protective walls, the experience of grief was the epiphany to shattering the legitimacy of claiming an impenetrable hardness.

Markus’s photograph conveyed the way that the loss of a friend acts as a moment of identity transformation, an experience that many other participants shared. Participants with previous commitments to patterns of stoic masculine practices found themselves surprised by powerful feelings and expressions of grief.

In the context of this study, the use of participant produced photos was critical in eliciting gendered experiences of grief. The images and accompanying narratives provided nuances to illuminate disjunctures (men distancing themselves from traditional masculinity) and prevailing practices (which maintain or were complicit in sustaining traditional masculinity). In addition, photographs illuminated a process of change toward contemporary masculinities evidenced in subtle yet powerful analogies and metaphors (e.g., grass growing through concrete).

Project 2: The Canadian Fathers Study

The Canadian Father’s Study (CFS) also combined semistructured interviews and PE to explore father roles, relationships, and practices with their children with particular focus on the issue of risk taking and safety. PE was used in this study to visually capture the environments in which men fathered as well as the way that they viewed themselves in a parenting role. Connell’s (1995) hegemonic and multiple masculinities framework was again used to understand the ways in which men positioned themselves as fathers in the context of familial patterns of gendered relations, social identities, space and place, and traditional and contemporary ideals of fathering.

Method

Despite the increased role of fathers in the lives of children (Harrington, Van Deusen, Fraone, & Mazar, 2015) much of the research into parenting has been conducted with mothers. Compared with research done on mothers and mothering, there have been relatively few investigations into the ways that fathers reflect on their relationships with children and the implications of father role strain (Silverstein et al., 2002) and depression (Edmondson, Psychogiou, Vlachos, Netsi, & Ramchandani, 2010). In the CFS, two interviews were conducted with 64 fathers, evenly dispersed between urban and rural regions in two Canadian provinces. Interviews were conducted in 2010-2013 by four trained female researchers and participants received a $50 honorarium for participation. The mean age of fathers was 37.8 years and, at the time of participation, fathers had at least one child between 2 and 7 years old. Thirty-six fathers were the sole earners in their families while 19 were in dual earning couples, 8 families had one parent on maternity/paternity leave and one family was on social assistance. The sample included fathers with a variety of family configurations and diverse forms of employment. Fathers were recruited using existing fathering networks listservs, placing ads in local papers and at local community centers, and snowball sampling methods. Recruitment and interviewing continued until we reached data saturation.

Data Collection

Following consent, researchers conducted a semistructured interview with participants, which covered their perceptions of fathering identities, their views on the gender relations between fathers and mothers, and orientation toward children’s risk and safety. Fathers were asked to consider the way they approached their parenting role and engaging with their children (Author, 2015). Participants were then given a photo guide with instructions as to the nature of photos required. In total, 992 photos were produced. Most images were digital photographs; however, a few participants also submitted images that they had downloaded from the Internet, reporting that they were unable to take photographs that accurately represented their perspective. The second interview was driven by these images which were uploaded and viewed on the researcher’s computer.

Data Analysis

Photos and narratives were uploaded to NVivo 10™ for coding and analyzed using the same three-stage process described in the Guys and Grief project (Oliffe et al., 2008) that involved examining photos from the perspective of participant, researcher, and through a theoretical framework. As the coding and writing proceeded, we examined in greater depth how masculine ideals influenced the ways men fathered and considered risk engagement and safety issues in the context of engaging their children.

Adapting the Approach

As in the Guys and Grief study, researchers were not overly prescriptive when guiding the men’s photo assignment efforts or in answering questions about the specificities of the task. The PE strategy used, however, evolved significantly over the course of this study. Initially, photo prompts were broad, allowing fathers to interpret the assignment as they wished and not prescribing particular responses (Table 2).

Table 2.

Original Photo Instructions for Canadian Fathers Study.

| Take some pictures of the things that concern your child’s safety, such as |

| Hazards you are concerned about |

| Ways you keep your child safe |

| Things that are helpful and unhelpful in keeping your child safe |

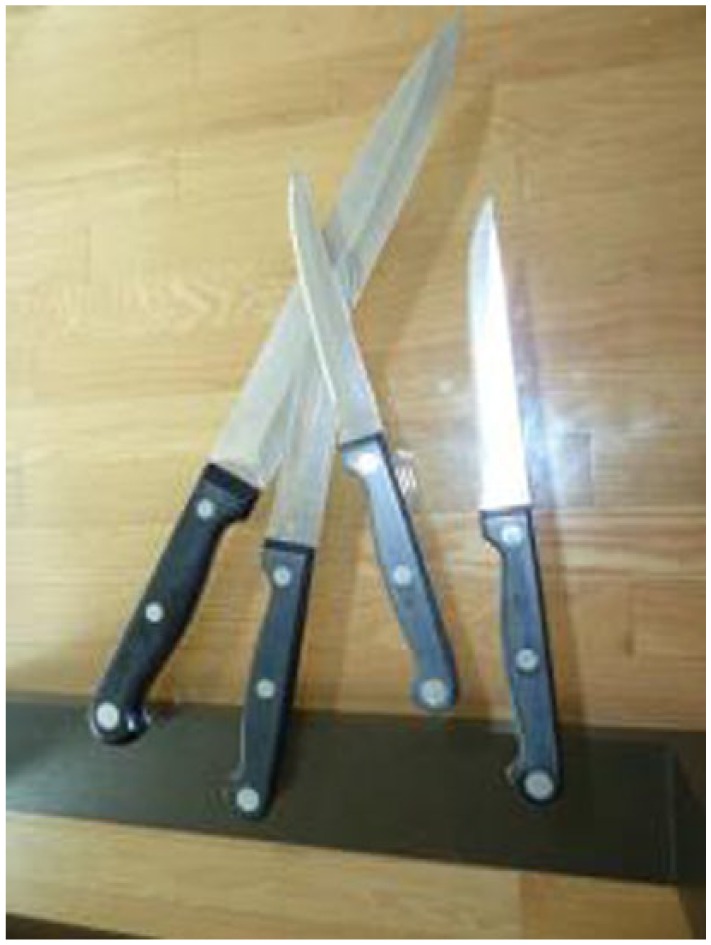

This set of instructions given to the initial six participants yielded many photos similar to those depicted below (Figures 5-7).

Figure 5.

Cross at the Cross Walk.

Figure 6.

Wear a Helmet.

Figure 7.

Avoid Sharp Knives.

As evident in Figures 5 to 7, fathers were taking photographs that, almost exclusively, fit in one of three themes: common outdoor hazards (play equipment, traffic, bodies of water), safety strategies (helmets, life jackets, proper storage of dangerous items), and common household hazards (knives, cords, poisons). While the photos confirmed that fathers understood injury risks as well as many appropriate injury prevention approaches, we found that the PE interviews were primarily didactic and did not enrich the conversation about risk and safety to the extent we had hoped. In addition, the photo prompts were not well matched with the initial interviews. While the first in-depth interviews opened up conversations about gender relations, fathering practices and balancing protection with gaining new experiences and capacities, the photos were most often concrete answers to the underlying question “what SHOULD you do?”

In response to these methodological challenges in our PE strategy, we adapted the photo assignment to explicitly ask fathers to consider the way that the community values of fathering influenced their own ideals about fathering with relationship to childhood risk and safety in their photo taking (Table 3). Following refinement of the photo assignment, photos illustrated the way that fathers balanced, with varying degrees of comfort, competing demands of fathering with respect to identities and roles of fatherhood. We found that this shift in PE strategy not only enriched both the photo and interview data but seemed to put the participant at ease, likely because of the relaxed nature of the interview and explicit avoidance of any interrogation about evaluating the men’s understandings about safety standards and strategies.

Table 3.

Adapted Photo Instructions for Canadian Fathers Study.

| Feel free to take pictures that are symbolic or ones that are concrete responses to the photo questionnaire. |

| 1. Take a picture (or pictures) of something that represents what you think it means to be a good father. |

| 2. Take a picture (or pictures) of something that represents what you think that others in your community would consider a good father. |

| 3. Take a picture (or pictures) of something you consider too risky for your child to do. |

| 4. Take a picture (or pictures) of something that might carry some risk but that you believe is important for your child to do or learn to do. |

| 5. Take pictures of things that you think other dads need to know about keeping kids active and safe. |

Results

This section highlights the ways in which PE was used to talk with fathers about how they thought about roles and relationships as they balance work and family. The benefits of PE were also evident in the way that they facilitated a discussion about specific examples and the emotional experience of fathering.

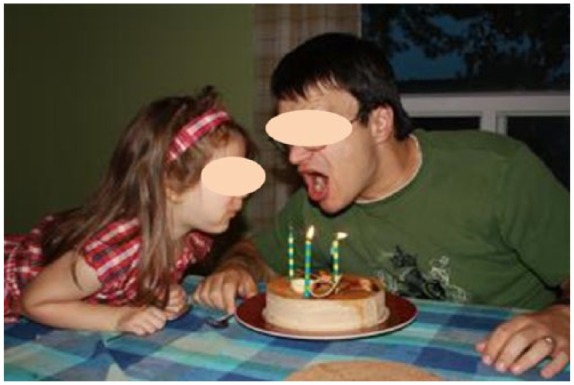

In response to the prompt “What does it mean to be a good father?” participants often produced photos that illustrated the dual roles that they assumed in their family, which included elements of both contemporary and traditional father identities. There were also images that depicted fathers in contexts demonstrating different commitments. For example, Pierre, a 36-year-old father of two, produced an image of himself and his daughter blowing out her birthday candles. Their heads are close together, portraying a close and engaged relationship (Figure 8): “A good father is a family man, someone who is involved. Not just in the dimension of being the breadwinner of the family. Maybe a more flexible notion than that, someone who is involved.”

Figure 8.

Father/Daughter Relationship.

Despite asserting the importance of going beyond the breadwinner role, Pierre also emphasized that his role in providing the family with its main source of income was also important to him. He included photographs of money (Figure 9) as well as a means to make money (Figure 10):

I realized that . . . and I also have that role in our relationship . . . there is a question of solidity, of stability and rationality that is associated with the role of the father . . . the father is a provider. It’s for sure that in my case, we’re a more traditional couple in that dimension. I bring home the biggest salary.

Figure 9.

Breadwinner.

Figure 10.

Earning money through labour.

It was important for Pierre to establish that his involvement with his children in no way superseded his masculine identity of, not only bringing home money to support the family but, as Figure 10 shows, earning this money through his labor. Interestingly, Pierre had a desk job rather than work with heavy machinery. He took this photo because he idealized fathers as “someone brave,” self-sacrificing in providing for family, intricately linking to physical elements romanticized in traditional masculinities. While he saw his own employment as “less impressive,” and perhaps less traditionally masculine, he made the point that his father role was firmly associated with breadwinner ideals in providing for his family.

These three photographs illustrate the connections and tensions between contemporary and traditional fathering practices wherein emotional nurturing and involvement with children are integrated with provider roles. At the same time that many men no longer subscribe to the notion that fathers and children should be distant, they maintain longstanding the masculine ideals that men should be the primary breadwinner. Congruently, while participants were willing to embody some roles traditionally assigned to mothers, these descriptions were accompanied by assurances that they have not abandoned the more socially valued performances of masculinity.

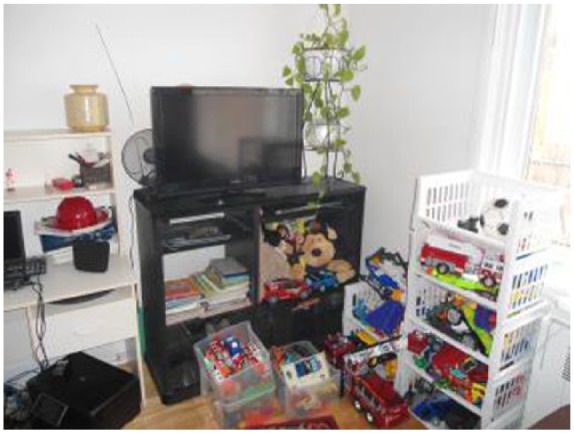

Harry, a 39-year-old father of a 7-year-old boy, transmitted a similar message, albeit, through the use of different images. His two photographs presented in this article featured both traditional “provider” role and contemporary “nurturer” role of father. His first photograph, in response to what constitutes good fathering, was of a room full of toys that he and his wife have purchased for their son (Figure 11). He reflected on the value that he placed on being able to provide his son toys and electronics for entertainment as well as the learning benefits that his son might gain from them:

And so, a good father, you have to not only. . . . With this photo, I wanted to talk about objects. I mean to say that he [the father] has to work a lot and earn his living.

Figure 11.

Providing for my son.

In describing a subsequent photo Harry explained that good fathers also have the obligation to engage with their children and participate in their development—a nurturer role. Figure 12 shows Harry playing with his son. Both father and son are smiling, clearly enjoying a fun activity together:

And also playing with him, that illustrates what it is to be a good dad too. We don’t only give him toys but you have to play with him because that is what he likes and it permits us to develop his distinct personality, our boy.

Figure 12.

Spending time.

Notably, while Figure 12 portrays an affectionate engagement between father and son, Harry highlights it as a means to an end in that playing with his son aids the boy’s development. The activity is therefore purposeful with outcomes and perhaps expectations attached to the active doing of fathering. Also evident is the consumer power made available through Harry’s work. In this regard, the nature of the products purchased is privileged as masculine capital residing above the type of the paid work.

This emphasis on teaching and guiding was also evident in Michael’s photos and narratives regarding his fathering role in his son’s life. A 40-year-old father of three, Michael spoke about bringing his 5-year-old son with him on construction sites to serve the dual purpose of spending time and teaching him (Figures 13 and 14):

Here, you see, that’s him with my tools. You see, he had a plank and he wanted to have a hammer and a screwdriver. Of course he’s too small for nails. He hits himself more on the fingers than anything else. He hits the plank with a hammer and a screwdriver. When I’m doing my deck or I’m doing my different construction projects, he’s always there to come work with me.

Figure 13.

Teaching Skills.

Figure 14.

He watches me at work.

André, a 45-year-old father of seven boys, used the image of a baseball cap and the metaphor of “coach” to frame his engagement with his children. He commented on the way that his fathering role involved understanding of the child’s problem and then developing a strategy to resolve the issues (Figure 15):

The baseball hat, that’s for the coaching side. When you’re a parent, it’s like you’re a coach as well. You can’t let them go just anywhere, any which way. There are ways of doing things. When there are harder things, we find strategies to succeed at what remains to be done. Once we’ve listened to the fears, the worries, we can coach to know how to overcome them. So that was the coach’s baseball hat.

Figure 15.

Coach.

While André maintained a high level of involvement in his children’s lives, he cast a traditionally masculine interpretation of this involvement. Acknowledging that parents wear many hats, he pictured the baseball cap as a means to convey the coach role in disciplining, advising and directing—all of which were generally accomplished in an outdoor sports setting.

CFS participant photographs provided evocative imagery and illustrated the ways in which fathers interpreted and reinterpreted their identities in the context of competing discourses of hegemonic masculinity and contemporary fathering. Common to Michael’s and André’s perspectives was the doing of fathering wherein work and leisure activities were the foundation for their children’s life lessons. The ethic of work and usefulness, for example, permeated Michael’s transmittal of masculine ideals to his son; while André clearly aligned to sports metaphors in being the coach to his team of boys. The intergenerational teachings of masculinity are central to the men’s accounts and contemporary fathering practices prescribing men’s direct involvement legitimate the teaching of somewhat traditional masculine ideals.

Discussion

The studies discussed in this article provide examples of the way that PE can help researchers and participants elucidate and abstract complex relationships between traditional embodiments of masculinity and the contemporary ideals espoused as new standards for manliness. As Affleck et al (2013) have argued, a qualitative investigation of an individual’s health and well-being that does not include the affective experience is left wanting. The use of photographs with men in the studies facilitated discussion about emotional experiences, the expression of emotion, reflection on the ways that participants construct masculinities in diverse contexts, the conflict between dominant social ideals of masculinity, and the lived experiences of men (Plunkett, Leipert, & Ray, 2013).

Emotion

While a narrative interview can quickly move into the theoretical or symbolic realm, a photo of one’s experiences of grief or of one’s children brought about discussion of the concrete and real-time emotional responses that accompany it. Rather than relying solely on the individual to reflect on the context of the interview, the participant has visual medium and mechanism to express perspectives on the phenomenon. The images also often served to trigger a cascade of emotive responses—many of which had been channeled by participants into the taking of the photograph in the first place. Afforded also by the authors, multiple meanings residing within the photographs were auto narratives purging free independent of the interviewers’ direct questions.

Masculinities

The images produced by men in this article illustrate how dominant constructions of masculinities are engaged by men in grief and fatherhood. In both studies, some men self-consciously distanced themselves from more traditional images of masculinity, embodied as stoic and impenetrable. Many participants spoke about how the powerful experience of grieving a loss or of becoming a father promoted sensitivity, softness, and some introspection. Photographs prompted self-disclosure and permitted the sharing of vulnerabilities, but the Guys and Grief study photographs also commonly portrayed images of concrete and other impenetrable objects. The CFS included fathers in the role of providing, teaching, and directing courting, and at times conceding the tensions inherent to attachment and removal. Men pictured themselves both within the context of grief and childrearing and also their emotional (Guys and Grief) and physical (CFS) absence from it. In this way, photographs captured continuities, as well as discontinuities, in the evolution of masculinity in a way that was not evident in the first verbal-only interview.

The use of PE methods can increase our understanding of the structures of masculinity and masculine identities by giving the participants power and agency as previously described by Oliffe and Bottorff (2007). An overview of a large collection of photographs, such as was produced in our studies, can yield an account of the social spaces that men occupy as they assume different identities. Most photographs, taken by participants in both studies, were outside, congruent with a traditional gender binary which associate masculinity and outdoor/public spheres and femininity with indoor/private spheres (Laurendeau, 2008). There was a notable contextual contrast evident in the photos taken by the young men in the Guys and Grief study and the fathers in the CFS. This was, in part, because of the different subject matter explored in the two studies but the marked difference also illustrates the way masculinities are dynamic shifting as men journey through diverse life course events. We reflected that commitment to the most emphasized embodiments of dominant masculinities may wane or become less important as men age. It was noteworthy that contemporary masculinities (e.g., emotional expressiveness, nurturing behaviors) were often only theorized by young men in the Guys and Grief study; men in the CFS actually practiced within the realm of renegotiated masculinities. Also evident is the robustness of the method wherein interiority as well as corporeal objects can be produced and narrated. Analysis of where men go to take photographs and what (or who) they choose to include, also assists with naming the characteristics of traditional and more contemporary versions of masculinity.

PE Methods and Masculinities

The process of adapting the photo instructions given to participants following initial interviews speaks to the necessity of continually evaluating the photo data and how participants are interpreting and responding to the assignment. This strategy was also instructive about the potential considerations when doing PE research with men. We found, for example, that we needed to balance giving precise instructions, aligning with a masculine ideal of “getting it right,” with giving an overly didactic assignment that precluded creativity and personal interpretation. Men, in both studies, were concerned about wasting our time and theirs by producing photographs that did not adequately contribute to the research. To allay this concern it was important, therefore, to reassure participants that there was “no right or wrong image” and that we were interested in the way that they interpreted their photographs and the photo assignment more broadly. If they could not think of an image to produce on a specific topic, participants were encouraged to move on to another theme. In terms of study design, it is clear that the processes used to direct participant’s photographs deeply influenced the depth of the images and the accompanying narratives shared by the men. In addition, the interiority of the study topics demanded introspection about what was said, as well as how it was represented.

Methodologically, we thoughtfully considered the effect of having female researchers interviewing men about grief and fathering. With the understanding that gender is coconstructed in interaction (West & Zimmerman, 2009) speculated was whether grieving young men would be more or less expressive or if fathers would construct their fathering role as more monolithic when speaking with a female interviewer. As Elliot (2005) argues research interviews should be seen both as a site for the production of data and as an opportunity to explore the interaction as an enmeshment of gender identities. While the gender of interview and interviewee does not necessarily produce better or worse data, reflecting on the posturing, performativities, and other potential influences is in line with the reflexivity central to qualitative health research.

PE was a good fit with the way that participants already engaged in the world. With cameras in cell phones and the proliferation of ways of producing and sharing images on the Internet, photographs are an ever more normative way by which many young and middle age people share their experiences with others. For these same reasons, talking through images in creative ways, through the use of analogies and metaphors to yield comparisons, is also an extension of that technology (Allen, 2008; Author, 2011) and is likely to be taken up much more often in the health research context. With this in mind, ethics review committee criteria for the use of this method have become more stringent with privacy issues paramount. The Guys and Grief study, for example, included permission for the use of photos only in the context of the initial consent form. The CFS, initiated a year later, included a photo release form signed by participants following submission of photos alongside the consent form. This two-step process ensures that participants are aware of the potential use of the photographs prior to taking them and have a second opportunity to reflect on how they might choose to limit dissemination. Participants in both studies were instructed not to take identifying photographs of others. Participants in the CFS study were assured that photographs of children would have faces blocked out, even if fathers gave us permission to use these photographs, to protect and respect children’s privacy in the era of the World Wide Web.

The challenges of using photo research are both material and methodological. There are logistical limitations, for instance, in retaining the participant throughout the multistep study. Another challenge is in the analyses. The products of visual methods can be particularly powerful for viewers, but Moran-Ellis et al. (2006) caution researchers to maintain a position of reflexivity. While an interview transcript might easily lend itself to deconstruction, there might be a temptation to construe pictures as more “truthful” and objective than words (Clark-IbáÑez, 2004). Moreover, the perspective and construction of an image maintains a kind of “authorless” state, where it is easy to forget that a picture has been framed and constructed by its author, as well as by the viewer. Phrases such as “a picture is worth a thousand words” or “pictures don’t lie” imply that images capture the truth and represent reality (Clark-IbáÑez, 2007). Likewise, photographic images are commonly used to present a socially desirable image of the self. For example, photographs that include an image of the participant (e.g., father and son) may be projecting a representation of how the participant would like to be seen or how he believes the researcher could be assured of his engaged fathering. However, the same constructivist and critical interpretations characterizing qualitative interviews apply in the analysis of the photograph, mandating that the researcher be reflexive about the limitations of narrations of self and other, regardless of the method chosen.

Despite some limitations, our experiences illustrate the value of PE methods to enhance in-depth interviews and generate insights that may not be visible in-depth interviews alone. It fosters the development of complex concepts that may have only partially understood through semistructured interviews or more positivistic methods such as surveys or structured interviews. In particular, herein we have emphasized their value for traditionally challenging populations and topics. Through these means, we have garnered insights regarding men and masculinities that would not otherwise have been available to us and you—and in doing so, we are privileged with innumerably rich material for sharing the knowledge etched within the images and narrated by authors and other viewers.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the men who participated in these studies, and to research team members Elizabeth Saewyc, Jennifer Matthews, Anne George, Pierre Maurice, David Sheftel, Dominique Gagné, and Sami Kruse.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This research and article were made possible by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Institute of Gender and Health) Grant No. OBM-101389, Grant No. IGO-103694 and MOP-111027.Career support for Creighton was provided by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR). Career support for Brussoni was provided by a MSFHR scholar award. Career support for Oliffe was provided by a MSFHR scholar award.

References

- Addis M., Mahalik J. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the context of help seeking. American Psychologist, 58, 5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affleck W., Glass K. C., MacDonald M. E. (2013). The limitations of language: Male participants, stoicism, and the qualitative research interview. American Journal of Men’s Health, 7, 155-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken S. (2009). The awkward spaces of fathering. Burlington, England: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Allen L. (2008). Young people’s “agency” in sexuality research using visual methods. Journal of Youth Studies, 11, 565-577. [Google Scholar]

- Allen L. (2009). “Snapped”: Researching the sexual cultures of schools using visual methods. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 22, 549-561. [Google Scholar]

- Berman H. (2001). Portraits of pain and promise: A photographic study of Bosnian youth. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 32(3), 21-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brussoni M., Olsen L.L. (2011) Striking a Balance: Father’s attitudes and practices towards child injury prevention. Journal of Developmental and Behavioual Pediatrics, 32(7), 491-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brussoni M., Creighton G.M., Olsen L.L., Oliffe J.L. (2013) Men on fathering in the context of children’s unintentional injury prevention. 7(1), 75-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. (2004). Undoing gender. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Catalani C., Minkler M. (2010). Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior, 37, 424-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, England: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Clark-IbáÑez M. (2004). Framing the social world with photo elicitation interviews. American Behavioral Scientist, 47, 1507-1527. [Google Scholar]

- Clark-IbáÑez M. (2007). Inner-city children in sharper focus: Sociology of childhood and photo-elicitation interviews. In Stanczak G. C. (Ed.), Visual research methods: Image, society and representation (Vol. 47, pp. 167-196). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W. (1995). Masculinities. Cambridge, England: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W. (2005). Masculinities (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W., Messerschmidt J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19, 829-859. doi: 10.1177/0891243205278639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W. (2011). Dying to be men: Psychosocial, environmental and biobehavioral directions in promoting the health of men and boys. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton G.M., Oliffe J.L. (2010) Theorizing masculinities and men’s health: A brief history with a view to practice. Health Sociology Review, 19(4), 409-418. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton G.M. (2011) Troubled Masculinity: Exploring Gender Identity and Risk-taking Following the Death of a Friend. (Doctoral Dissertation) Retrieved from UBC Circle https://circle.ubc.ca/handle/2429/37961

- Creighton G., Brussoni M., Oliffe J. L., Olsen L. L. (2015). Fathers on child’s play: Urban and rural Canadian perspectives. Men and Masculinities. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1097184X14562610 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton G.M., Oliffe J.L., Matthews J., Saewyc E. (2016) "Dulling the Edges": Young Men’s Use of Alcohol to Deal With Grief Following the Death of a Male Friend. Health Education and Behaviour, 43, 54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly K. (1993). Reshaping fatherhood: Finding the models. Journal of Family Issues, 14, 510-530. doi: 10.1177/019251393014004003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dey I. (1999). Grounding grounded theory: Guidelines for qualitative inquiry. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dowdall G. W., Golden J. (1989). Photographs as data: An analysis of images from a mental hospital. Qualitative Sociology, 12, 183-213. [Google Scholar]

- Drew S. E., Duncan R. E., Sawyer S. M. (2010). Visual storytelling: A beneficial but challenging method for health research with young people. Qualitative Health Research, 20, 1677-1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson O. J. H., Psychogiou L., Vlachos H., Netsi E., Ramchandani P. G. (2010). Depression in fathers in the postnatal period: Assessment of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening measure. Journal of Affective Disorders, 125, 365-368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot J. (2005). Using narrative in social research. London, England: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J. (2005). Using narrative in social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington B., Van Deusen F., Fraone J. S., Mazar I. (2015). The new dad: A portrait of today’s father. Boston, MA: Boston College Center for Work & Family. [Google Scholar]

- Hurworth R. (2003, Spring). Photo-interviewing for research. Social Research Update—Sociology at Surrey, 40, 1-4. [Google Scholar]

- Keller C., Fleury J., Perez A., Ainsworth B., Vaughan L. (2008). Using visual methods to uncover context. Qualitative Health Research, 18, 428-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohon J., Carder P. (2014). Exploring identity and aging: Auto-photography and narratives of low income older adults. Journal of Aging Studies, 30, 47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurendeau J. (2008). “Gendered risk regimes”: A theoretical consideration of edgework and gender. Sociology of Sport Journal, 25, 293-309. [Google Scholar]

- Levant R. (2008). How do we understand masculinities? An editorial. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 9, 1-4. [Google Scholar]

- Levant R., Pollack W. (2001). A new psychology of men. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Moran-Ellis J., Alexander V. D., Cronin A., Dickinson M., Fielding J., Sleney J. (2006). Triangulation and integration: Processes, claims and implications. Qualitative Research, 6, 45-59. [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Bottorff J. L. (2007). Further than the eye can see? Photo elicitation and research with men. Qualitative Health Research, 17, 850-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Bottorff J. L., Kelly M. T., Halpin M. (2008). Analyzing participant produced photographs from an ethnographic study of fatherhood and smoking. Research in Nursing and Health, 31, 529-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Mroz L. (2005). Men interviewing men about health and illness: Ten lessons learned. Journal of Men’s Health and Gender, 2, 257-260. [Google Scholar]

- Packard J. (2008). “I’m going to show you want it’s really like out here.” The power and limitation of participatory visual methods. Visual Studies, 23, 63-77. [Google Scholar]

- Paechter C. (2003). Masculinities and femininities as communities of practice. Women’s Studies International Forum, 26, 69-77. [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett R., Leipert B. D., Ray S. L. (2013). Unspoken phenomena: Using the photovoice method to enrich phenomenological inquiry. Nursing Inquiry, 20, 156-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommper D. (2010). Masculinities, the metrosexual, and media images: Across dimensions of age and ethnicity. Sex Roles, 63, 682-686. [Google Scholar]

- Schippers M. (2007). Recovering the feminine other: Masculinity, femininity, and gender hegemony. Theory and Society, 36, 85-102. [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe M., Wolkomir M. (2001). The masculine self as a problem and resource in interview studies of men. Men and Masculinities, 4, 90-103. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein L. B., Auerbach C. F., Levant R. (2002). Contemporary fathers reconstructing masculinity: Clinical implications of gender role strain. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 33, 361-369. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2012). Table102-0561: Leading causes of death, total population, by age group and sex, Canada (annual). Retrieved from http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=1020561

- Wall G., Arnold S. (2007). How involved is involved fathering? An exploration of the contemporary culture of fatherhood. Gender & Society, 26, 508-527. doi: 10.1177/0891243207304973 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Burris M. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24, 369-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West C., Zimmerman D. H. (2009). Accounting for doing gender. Gender & Society, 23, 112-122. [Google Scholar]