Abstract

Past research has suggested that social support can reduce the negative psychological consequences associated with infertility. Online discussion boards (ODBs) appear to be a novel and valuable venue for men with fertility problems to acquire support from similar others. Research has not employed a social support framework to classify the types of support men are offered and receive. Using template, content, and thematic analysis, this study sought to identify what types of social support men seek and receive on online infertility discussion boards while exploring how men having fertility problems use appraisal support to assist other men. One hundred and ninety-nine unique users were identified on two online infertility discussion boards. Four types of social support (appraisal, emotional, informational, and instrumental) were evident on ODBs, with appraisal support (36%) being used most often to support other men. Within appraisal support, five themes were identified that showed how men communicate this type of support to assist other men: “At the end of the day, we’re all emotionally exhausted”; “So much of this could be me, infertility happens more than you think”; “I’ve also felt like the worst husband in the world”; “It’s just something that nobody ever talks about so it’s really shocking to hear”; “I say this as a man, you’re typing my thoughts exactly.” These findings confirm how ODBs can be used as a potential medium to expand one’s social network and acquire support from people who have had a similar experience.

Keywords: infertility, men, male factor infertility, online discussion board, social support

Introduction

Infertility, defined as the inability to achieve a pregnancy after 12 months of unprotected sexual intercourse (Zegers-Hochschild et al., 2009), affects 14% to 16% of couples in North America (Bushnik, Cook, Yuzpe, Tough, & Collins, 2012; Chandra, Copen, & Stephen, 2014). Research exploring the psychosocial consequences of infertility indicates that both men and women experience a wide range of negative outcomes including anxiety, depression, guilt, hopelessness, lowered self-esteem, and social strain (Cousineau & Domar, 2007; Dhillon, Cumming, & Cumming, 2000; Epstein, Rosenberg, Grant, & Hemenway, 2002; Smith et al., 2009). The stresses associated with infertility do not always lead to adverse psychological and social outcomes (Greil, Slauson-Blevins, & McQuillan, 2010; Hanna & Gough, 2015). For example, infertility can have both positive and negative effects on the couple by altering the quality of their sexual, social, and emotional relationship (Peterson, Pirritano, Christensen, & Schmidt, 2008).

For individuals going through adverse life events, social support from family and friends has been linked to reduced feelings of depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and to better quality of life (Cobb, 1976; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Vanderwerker & Prigerson, 2004). Studies focusing on the life crisis of infertility have revealed the importance of social support in coping with diagnosis and treatment (Agostini et al., 2011). Social support occurs when people share resources such as information, services, or emotional support, to benefit the person who receives those resources (Shumaker & Brownell, 1984). Social support may be most effective when the person providing support is similar in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, and has lived through similar life experiences as the individual experiencing the life crisis (Albrecht & Adelman, 1984; Vayreda & Antaki, 2009; Wang, Walther, Pingree, & Hawkins, 2008). Although beneficial for both genders, men are less likely than women to take advantage of social support (Cousineau & Domar. 2007; Harrison, MacGuire, & Pitceathly, 1995). Male factor infertility is frequently associated with high levels of social stigma due to the association of fertility with masculinity and sexual potency (Gannon, Glover, & Abel, 2004). As infertility can threaten a man’s self-image, it can result in feelings of depression, isolation, and a fear of disclosure, further reducing active support–seeking behaviors (Oliffe & Phillips, 2008; Schmidt, 2009).

Social support can be classified into one of four categories based on its defining attributes. These are informational, appraisal, emotional, and instrumental support (Langford, Bowsher, Maloney, & Lillis, 1997). Informational support refers to the provision of information that helps one problem solve during periods of stress. Appraisal support involves the communication of information relevant to self-evaluation and affirming the appropriateness of acts or statements made by the recipient. Emotional support is conveyed through the provision of empathy, love, caring, and trust. Finally, instrumental support is defined as the provision of tangible goods, services, or assistance. As social support is a reciprocal act, knowing the type of support an individual is seeking would allow the support provider to best assist the person based on their self-identified needs.

In coping with the psychosocial consequences of infertility, women tend to seek out social support more actively, while men tend to cope through avoidance and keep their emotional distress to themselves (Kowalcek, Wihstutz, Buhrow, & Diedrich, 2001). In infertility-related communication, men tend to rely mostly on secretive or formal communication, whereas women tend to be more open in talking about both facts and feelings related to infertility (Schmidt, Holstein, & Christensen, 2005). These gendered differences may reflect the fact that men have traditionally been socialized to contain their emotions, while women have been socialized to be more emotionally open and sensitive (Harrison et al., 1995; Kiss & Meryn, 2001; Wallace, 1999). For example, in a study comparing online communication between breast cancer and prostate cancer patients, women were more likely to use words related to emotional disclosure, while men were less likely to seek emotional support and used a communication style focused on information (Owen, Klapow, Roth, & Tucker, 2004). Although this study reports a gendered style of communication, there is evidence that men having fertility problems do engage in more emotion-focused disclosure in mixed gender online communities (Mo et al., 2009). These studies emphasize the need to take into consideration contextual factors affecting the discourse between men and women on differing online support group discussion boards.

A growing number of infertile couples are using the Internet to obtain medical information and social support (Epstein et al., 2002; Hanna & Gough, 2016b; Hinton, Kurinczuk, & Ziebland, 2010; Malik & Coulson, 2008b). Men tend to use online support groups more frequently than face-to-face support groups to acquire advice and assistance (Dwyer, Quinton, Morin, & Pitteloud, 2014). These online groups can be especially beneficial for men having fertility problems due to the stigmatized nature of their condition (Berger, Wagner, & Baker, 2005). Online support groups have a number of advantages distinct from traditional support groups including: user anonymity, optional disclosure, lack of geographic barriers, and an asynchronous communication style (White & Doorman, 2001). These support groups can broaden one’s social network to include individuals with a similar experience of infertility, which may encourage men to seek support online (Malik & Coulson, 2008b; Mo et al., 2009).

Most research on online fertility support groups has focused on the experience of women (Epstein et al., 2002; Malik & Coulson, 2008a, 2010, 2011). It is important to address this disparity while identifying men’s needs in terms of social support (Culley, Hudson, & Lohan, 2013; Petok, 2015). The limited data on men’s experience of online support groups for infertility indicate that men used online discussion boards (ODBs) as a place to acquire support and as an outlet for hidden emotions, to which other users responded by drawing on their first-hand experiences to communicate information relevant to self-evaluation (Hanna & Gough, 2016a, 2016b; Malik & Coulson, 2008b). Thus, as has been reported in studies of online support groups for men with cancer and adolescents who self-harm (Smithson et al., 2011; Stephen et al., 2014), it appears that men use appraisal support to reach out and assist one another. To date, there have been no studies categorizing the types of support men seek and receive within ODBs for infertility.

The purpose of the present study was to explore communications by men within ODBs to identify which types of support men having fertility problems seek and receive through this medium. In this study, Langford et al.’s (1997) framework of social support was used to categorize support. As ODBs present themselves as a useful venue for men to normalize the experiences of other men with fertility problems (Hanna & Gough, 2016a, 2016b; Malik & Coulson, 2008b), an in-depth analysis of appraisal support would allow us to understand this supportive approach in further detail. To achieve this goal, template, content, and thematic analysis were used to categorize supportive messages based on their content. Specifically, the research questions are as follows:

Research Question 1: What types of support do men having fertility problems seek and receive on OBDs?

Research Question 2: How do men having fertility problems use appraisal support to assist others on OBDs?

Method

Data Collection

The data for this study were messages posted on ODBs between January 2014 and July 2015 and were collected between September 1 and September 6, 2015, by researchers in Canada. The ODBs were located on a popular social networking website allowing members to submit text posts anonymously, making it an attractive option for people searching for support. The social networking website is split into communities covering a range of men’s psychological and physical health issues. The current study examined two ODBs: one focusing on male-specific infertility and the other on general infertility. Both ODBs welcome men with fertility problems to discuss their personal experiences and provide support for one another. The messages from both ODBs were combined in the analysis for a total of 51 threads consisting of 546 messages. Messages identified the date and time of posting with the sender’s name followed by the text.

Sample

The present study was interested specifically in men’s use of ODBs; therefore, threads initiated by women were excluded from the data set. As a result, all of the support seekers included in this study were men. Replies to male-initiated threads by both genders were included in the analysis as these replies were a form of social support for male members. The gender of the sender was identified by the tags included with their username, the type of infertility they were experiencing, and the mention of gender in their public post history. In total, 199 unique sender names were identified. Within the ODB specifically for male infertility, 66% of the comments were posted by men, 30.2% by women, and 3.8% of users had an unidentifiable gender. Comment replies in the general infertility ODB were mostly posted by women (75%) though there was a significant male presence (25%). Generally, the individuals posting on the ODBs appeared to be attempting to cope with their diagnosis of infertility or were undergoing testing and/or treatment for both male and female factor infertility. Due to the range of infertility concerns mentioned by male users, they will be referred to as “men having fertility problems” throughout the analysis.

Analysis

Messages were analyzed using a combination of template, content, and thematic analysis. The template for the current analysis was based on Langford et al.’s (1997) typology in order to have a priori categories of support to guide further analyses (King, Cassell, & Symon, 2004). While content analysis can be used to characterize and understand the relative prevalence of a construct (Chen, 2014), thematic analysis allows one to identify, analyze, and record patterns within the data set (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Merging these methods allowed us to (1) categorize various types of support identifiable within ODBs, (2) characterize the relative prevalence of social support, and (3) acquire a deeper understanding of the provision of social support within ODBs. First, the messages within the data set were differentiated by whether the user was asking for support or providing support to another user. For a user to be asking for support, the comment had to be an explicit solicitation of assistance. For example, a user could state that he is “just looking for any input whatsoever” or could ask whether “anyone has some insight on what to expect.” As for the provision of support, these messages were identified as such if they were offered as a supportive response to the original thread. Second, the messages were read carefully to identify which type of support they contained based on Langford et al.’s (1997) typology of social support. This typology was chosen because it comprised a small number of categories and a clear and comprehensive template with which to classify online messages. Social support can be classified into one of four categories: informational, appraisal, emotional, and instrumental. In the context of ODBs for infertility, informational support was identifiable when users sought medical information about their diagnosis or various treatments and associated side effects. Appraisal support was coded when individuals were looking for shared experiences as feedback and affirmations for their own personal decisions with infertility. Emotional support involved the communication of empathy and understanding for the experience of infertility and the provision of hope for future treatment outcomes. As the study was conducted online, it was expected that the provision of tangible goods or assistance would be less evident. The definition of instrumental support was in consequence broadened to include directive suggestions meant to provide practical assistance for everyday activities (Evans, Donelle, & Hume-Loveland, 2012). For example, a user could be guiding another in how to support his wife by telling him forthrightly to “Rub her feet. Offer to get takeaway if she doesn’t feel like cooking. Be her rock.” A single comment could include more than one type of social support, as the defining attributes of support are not mutually exclusive. Third, the data were systematically reviewed to identify themes inductively within the content coded as appraisal support. This analysis was conducted in an essentialist/realist framework which aims to report the experience, meaning, and reality of participants and the themes were identified within the explicit meaning of the text (Braun & Clarke, 2006). A software program developed to assist qualitative data analysis, Nvivo 9 (QSR International, Victoria, Australia), was used to facilitate this process. Fourth, 22% of the content was chosen at random and reviewed by a second rater who was trained in the present coding scheme. After review, the codes were compared and an interrater reliability of 90% agreement was achieved. The codes not agreed on were discussed in detail and a decision about coding was made by consensus of both raters.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations relevant to this study are centered predominantly on issues of privacy, confidentiality, and informed consent surrounding open-source online data. Eysenbach and Till (2001) have identified multiple key aspects of ODBs which must be met in order for ethical consent to be waived. The first of these is that the postings on the website be publicly accessible and not require registration to be viewed. The host website used for the analysis is open and does not require registration to view posts. Second, online communities need a membership size of over 100 unique users to further emphasize their open access and public nature. In the communities observed, membership ranged from 250 to 4,000 users and subscription to the individual community was not necessary in order to post on the discussion board. Third, individuals’ perception of the “public” versus “private” nature of the website must be taken into consideration prior to using ODB posts as research data without gaining consent (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, & Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, 2014). Within the website observed there is an option to make individual communities private and individuals also have the option to send private messages or to submit public posts. The communities observed were not private and the host website is accessed by over one million people every day, removing any reasonable expectation of privacy. Finally, according to Eysenbach and Till (2001), the data analysis has to be conducted in a nonintrusive manner in communities that do not explicitly require consent for research. The authors did not post on the ODBs and there was no explicit restriction on using posts for research within the community guidelines. As all of these conditions were met within the ODBs observed, research ethics committee approval and informed consent were not required and members were not contacted prior to and during the research project.

Based on the approach and precedents established by previous authors (Hanna & Gough, 2016a, 2016b; Malik & Coulson, 2008b), utilizing data from open online sources was deemed ethical and essential in further understanding men’s experience in acquiring support for infertility online. Learned society guidelines were utilized throughout the research project (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2014) to ensure the privacy and autonomy of individuals using the ODBs. All usernames were anonymized through a unique numbering system and coded based on the member’s gender, namely, M for male and F for female (e.g., M010), in the early stages of the study and remain so in this report.

Results

What Types of Support Do Men Having Fertility Problems Seek and Receive on Online Discussion Boards?

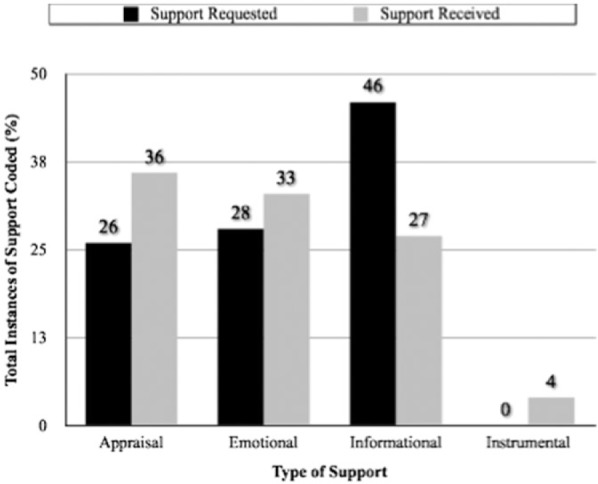

Figure 1 summarizes the different categories of support sought and provided. Out of the 546 total comments included in the analysis, 418 comments were coded as having at least one instance of support. Within these 418 supportive comments, 540 unique instances of support were identified. Seventy of the 540 instances were requests for support, whereas the remaining 470 were supportive responses.

Figure 1.

The proportion of each instance of social support requested (n = 70) and received (n = 470) within online discussion boards.

Informational Support

This type of support was requested most often: 32 (46%) requests for and 129 (27%) responses of informational support were identified. Direct requests for information or advice were often used in order to further understand one’s diagnosis and to seek suggestions for what they should do moving forward with treatment.

I just got my test results and the Dr said I have no sperm in my ejaculate . . . I was wondering if anyone knows what I am looking at. (M005)

As a response to these requests, other users would answer based on what they best understood from their personal research and/or what their doctor had recommended.

The medical term for your condition is azoospermia so start googling that. As mentioned, you have either non-obstructive (your body isn’t making sperm) or obstructive (your body makes sperm but it is trapped inside due to a blockage). (M003)

In cases where requests for information were more complex and scientific, users would refer these men to alternative sources of scientific information or suggest that they go to see their health care provider with these questions.

Haven’t heard of that issue before. Have you seen a urologist? If not, I cannot encourage you strongly enough to do so. (M012)

Appraisal Support

This type of support was most frequently offered though it was less often requested than informational and emotional support: 18 (26%) requests for and 168 (36%) responses of appraisal support were identified. When appraisal support was desired, users began by sharing their current situation and asked other users whether they had lived through a similar experience.

My wife and I have been [trying to conceive] for about a year . . . [my urologist] prescribed Clomid for me. I’m just wondering if anyone here has experience with clomid for male factor subfertility? (M012)

Appraisal support was given as a response to provide other men with information relevant to self-evaluation. For example, if a man asked for information about using donor sperm, a supporter would begin by validating his experience and sharing his perspective on the issue.

It’s not just your wife, both of you have a son. I’ve already painfully accepted the sad reality that I’ll most likely will never become a father biologically. But whatever children my wife and I do gain in time . . . it wouldn’t matter to me. This is because I will be their father. (M033)

Users would also offer appraisal support to normalize the feelings of men seeking emotional support by sharing how they too “haven’t experienced more sadness than I have with the loss of a pregnancy [or] failed attempts to have a child” (F006).

Emotional Support

Twenty (28%) requests for and 153 (33%) responses of emotional support were identified. Many of the men used the ODBs as an outlet to vent their emotions. Men often mentioned how, “where we come from this is a social stigma so we cannot even raise money or talk to someone . . . its either this forum or [my wife]” (M113). In response, men would mention how “I totally understand how you feel” (M046) and offered reassurance by saying, “just wanted to let you know you’re not alone” (M005).

Emotional support was often used to show empathy and understanding of one’s current condition, failed treatment experience, or relationship with friends and family. Although these people were communicating online, a depiction of caring and admiration was apparent within their comments:

That sucks, man. Sorry to hear it. The best thing I can tell you is this: learn to love yourself first . . . It’s all OK. And the way to make things better is to understand that. (M078)

Additionally, emotional support was used to convey hope and to wish others the best moving ahead in their life.

I’m praying for you and hope you can get through this . . . Please keep fighting, later you won’t regret it. (F010)

Instrumental Support

No (0%) requests for instrumental support were identified. Nonetheless, 20 (4%) responses to requests for other types of support were coded as containing instrumental support. When users responded to solicitations of support using instrumental support, it was often through the provision of practical coping strategies. This kind of support was used to guide others in how to move ahead with their treatment or how to support their partner in times of elevated distress, with an emphasis on being directive rather than helping one problem solve.

Offer to attend as many appointments as you can with her. Ask questions. If you can’t go to an appointment, ask her about it afterwards. Ask her how she is feeling . . . Be part of the process. (F032)

How Do Men Having Fertility Problems Use Appraisal Support to Assist Others on Online Discussion Boards?

The results of this study revealed that users offered appraisal support most often to assist other men. The analysis of these messages resulted in five key themes for how users relied on appraisal support to assist other men in their experience of infertility: (1) “At the end of the day, we’re all emotionally exhausted”; (2) “So much of this could be me, infertility happens more than you think”; (3) “I’ve also felt like the worst husband in the world”; (4) “It’s just something that nobody ever talks about so it’s really shocking to hear”; (5) “I say this as a man, you’re typing my thoughts exactly.”

Theme 1: “At the End of the Day, We’re All Emotionally Exhausted.”

A recurring theme in providing appraisal support was to normalize the roller-coaster of emotions men were experiencing in regard to their infertility. Men expressed a broad range of negative emotions yet these were often followed by the hope that their efforts would result in successful treatment outcomes. As one man seeking support mentioned:

I don’t know if expecting failure helps. I think it always hurts no matter what. I just allow myself to feel how I feel. Most of the time I’m pessimistic but sometimes I’m hopeful. (M099)

This quote portrays how men felt mixed emotions and had conflicting thoughts in response to their fertility treatment. Regularly, these men were supported through affirmations of the appropriateness of their emotions and the importance of verbalizing them to someone who would listen and understand.

Your feelings are completely normal and it’s not healthy to keep them bottled up inside. It’s cathartic to air them to someone who can listen objectively. (F024)

As men explicitly mentioned, “I didn’t think I could talk to anyone about this, much less post it on the internet” (M101), the discussion boards were reported as being a safe space to do so. The method of normalizing men’s feelings through one’s own experience would make the similarities between these men more explicit and allowed them to communicate on a personal level. Appropriately, some men would look specifically for this type of support and expected others to share their own experience within their comment.

I don’t post that much . . . but i wanted advice off of REAL people . . . who have been in similar situations. (M076)

Receiving a response which reduced negative self-evaluations and helped men realize how “at the end of the day, we’re [all] emotionally exhausted” (M038), reportedly made these men feel better.

Thanks for you[r] kind words everyone. It really does help to know that I can share my feelings with people who understand what I’m going through. (M002)

Theme 2: “So Much of This Could Be Me, Infertility Happens More Than You Think.”

As men primarily looked for information on ODBs, a recurring theme within the discussion boards was to convey information through one’s personal experience of infertility. This was notable when men were asking about their infertility to further understand their condition, diagnosis, or current symptoms.

Since a few guys here have had surgical sperm extraction or aspiration, I wonder if anyone lives with chronic testicle pain. (M063)

In this context, men were not asking for general information, but rather for information relevant to self-evaluation, which would affirm the normality of side effects following a surgical procedure. Additionally, it appeared that men asked for appraisal support to identify with others diagnosed with infertility and in turn reduce their sense of isolation through a shared experience:

I was born with no testicles so [my] body doesn’t produce testosterone or semen. What about you? (M033)

Sperm count, motility and morphology are all low. I’m clueless as to why that is the case. (M063)

In response, men regularly shared their own diagnosis of infertility and stated how, “for some of us, it’s going to be a reality we must face” (M122) and were relieved to hear how their condition “happens more than you would think” (M045). Although many men had difficulty accepting their diagnosis, they understood the reality of their condition and how they would need to undergo treatment to have children.

So much of this story could be me. Have you thought about sperm extraction surgery? I am azoospermic. . . . They chopped open my testes and I had a baby. (M063)

Men would also ask for information to help their wives cope with treatment outcomes of various procedures. As a result, ODBs were not only used to discuss issues relevant to their own self-evaluation but also to benefit their intimate relationship.

The wife and I are starting IVF in a few months. . . . Please could anyone give any advice. . . . How will the hormone injects affect the wife’s moods? (M076)

After receiving responses of self-relevant information from individuals struggling with infertility sharing how “I am sorry we are stuck in this boat together . . . it hurts so bad and is expensive” (F145), many of the men using the ODB reported that “this was pretty much exactly the kind of feedback I was looking for” (M050).

Theme 3: “I’ve Also Felt Like the Worst Husband in the World.”

Men frequently reported that they felt isolated from their wives in terms of the treatment process and their male factor infertility. If the primary cause of infertility was male factor, men would mention how “I’m really disappointed [and] I have a feeling [my wife] holds me responsible for it” (M083). In response to these messages, men would state how they too have “felt like the worst husband in the world” (M133) and feel “so many things and don’t know how to voice them” (M052). As such, appraisal support served to display how spousal conflicts are not atypical within infertile couples.

For me, I felt like less of a man. Like it was my fault. . . . You’ll fight with each other, you’ll feel like you’re fighting the world . . . if you can rely on each other and build each other up, you’ll get through it. (M088)

Sharing these thoughts allowed men to feel understood and experience a sense of relief as they no longer had to hide their emotions. As one man expressed, “Thanks, it’s good to know someone out there can understand how I feel” (M002).

Often, men made it clear that they did not know how to openly discuss their feelings with their wives when facing negative treatment outcomes. Although female supporters suggested men should not “keep it all away from your wife forever” (F001), some men were reluctant to communicate openly. As a man said, “Believe me, I wish I could share my feelings with [my wife]” but feared “she would get depressed herself, and then it’s me who has to help her” (M002).

In other instances, men stated how they had “absolutely no idea how [to] be supportive” (M029) when the treatment only directly involved their partner. The responses to these solicitations of support would often include personal experiences of how other men had been able to assist their wives. These users argued that this not only helped their partner but also had the benefit of bringing them closer together as a couple.

As a fellow father-to-be, what I try to do is just participate in as much as I can with her . . . I found that once I started trying to be more involved it really helped me cope and heal myself. (M118)

Theme 4: “It’s Just Something That Nobody Ever Talks About so It’s Really Shocking to Hear.”

Men not only felt isolated and withdrawn from their wives but expressed similar feelings regarding family, friends, and coworkers. Although in some cases, social network members were supportive of the couple during their fertility treatment, men stated how support from these sources was unreliable as they did not “understand what we have to go through” (M101). Through the use of appraisal support, users were able to normalize these experiences and offer assurance that their negative reactions are to be expected in such situations. One user mentioned how:

I want to love my hapless parents, but much of the time it is very hard to. Neither of them really know or care about this problem. (M089)

These feelings of isolation and disconnection from close family members were explicitly stated several times by both men and women. To this end, ODBs served as a medium through which members could vent their feelings and connect with individuals who have experienced similar hardships:

I get it. My brother in law’s wife has had two kids and everytime we are over at her house she complains on how hard it is to have kids and raise them. . . . She pisses me off so much. (M101)

Due to the social stigma associated with infertility, some men assumed that if their relatives knew they were infertile, it would negatively influence the way they interact with them. This was based on the assumption that infertility is “just something that nobody ever talks about so it’s really shocking to hear” (M030). As one user mentioned:

What I hate most are the thoughts I can’t help about what people think when they talk to me. Is it pity? . . . I’m so conflicted because I know I’d feel the same way as those people if the tables were turned. (M154)

Supporters often mentioned how “so many of us put up with the most asinine shit either because we ‘can’t’ say something (‘it’s family!’) or because we are too afraid of the fall out” (F024). As individuals often reported negative interactions within their actual social network, ODBs appeared to offer a positive peer support group allowing these men to say what they truly felt without fear of consequences.

Theme 5: “I Say This as a Man, You’re Typing My Thoughts Exactly.”

The connectedness of users on ODBs was motivated by the fact that they were all experiencing some form of fertility issue. Although support by both men and women was welcome, men often appeared to be most appreciative of appraisal support coming from other male users. Men stated how:

Fertility forums being principally populated with females (rightfully so!) and I found navigating those forums tricky because I felt I needed to speak to other men. (M003)

Supporters would often make their gender explicit in their comments by mentioning how they “say this as a man” (M088) and how they are “stuck in this boat together” (M098). This was noticeable when a man was looking for support after another failed treatment attempt. Through sharing similar hardships, men seemed to reinforce and encourage one another’s efforts. Men would mention how all of those trying to become fathers “are strong for going through this” and how “nothing can defeat the desire to have children” (M166). This type of relatedness was also seen in men looking for support after being diagnosed with infertility:

Just wanted to let you know you are not alone . . . I felt like such a failure as a man after I found out I had azoospermia. . . . Hang in there buddy, it gets better. (M005)

As this comment shows, men were sharing their personal experience of infertility, which was interpreted as an attempt to show empathy and normalize what they were going through. As supporters also experienced infertility as something negatively affecting their quality of life and self-perceptions as men, the provision of appraisal support allowed these men to feel empowered as they realize they are “strong for going through this” (M054).

Furthermore, this shared male experience appeared to be important when men were discussing tests or treatments that were only experienced by the male gender. Although women were able to share what their husbands had experienced, the male perspective was most valued as men were “typing my thoughts exactly” (M075). In a thread on the topic of sperm banking, a man was looking for support and information on whether there were “benefits to ejaculating twice” (M043). In response, both genders acknowledged his solicitation of support yet the advice given by men was taken over the advice by women:

I appreciate a comment on my post [F008], but . . . I will follow [M063]’s advice regarding talking only to the doctor. (M043)

As appraisal support involves the approval of one’s decisions or normalizing one’s experience through a shared reality, a male perspective appeared to be necessary to fully understand and affirm a man’s experience.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the types of support men having fertility problems seek and receive on ODBs while using thematic analysis to categorize the ways in which these men use appraisal support. The content analysis of online posts revealed that men sought out informational support most often, followed by emotional and appraisal support. Interestingly, the supportive responses men received did not follow the same order of frequency, with appraisal support being provided most often, followed by emotional, informational, and instrumental support. Requests for appraisal support appeared to encourage individuals communicating online to relate their own experience of infertility while normalizing the experience of others. This perspective allowed supporters to take a more personal approach to reassure men having fertility problems, while at the same time offering sympathy and understanding toward their situation. Although men looked for informational support most often, users relied predominantly on appraisal support when responding to solicitations of advice. Although there were instances of emotional and informational support integrated within instances of appraisal support, the latter was the main source of support within these messages. It is of note that instrumental support was never directly requested and was only delivered in the form of directive suggestions meant to provide practical assistance. This corroborates the past literature suggesting that instrumental support is not a significant component of online peer support (Evans et al., 2012).

By definition, both informational and appraisal support involve the provision of information. They differ in terms of intent and the way in which the supportive response is delivered. While informational support is based on helping one problem solve during a stressful situation, appraisal support involves the communication of information to aid in self-evaluation and to affirm the acts of the other person (Langford et al., 1997). In this study, users often shared their own experience in order to provide men with information and to indicate how they acquired knowledge of the topic at hand. Through appraisal support, this type of information was oriented toward normalizing and upholding the other person’s decisions rather than problem solving for them.

In agreement with past literature on gender differences and online support–seeking behaviors for infertility, the men in this study did request informational support most often (Malik & Coulson, 2010, 2011; Mo et al., 2009; Wallace, 1999). Responses to these requests for support often included information to assist in problem solving through one’s personal experience of infertility. As this study and others have identified, users may not have considered themselves as qualified to give scientific information and instead guided men toward other sources of information or their health care provider (Sillence, 2013). This result is interesting as existing studies emphasize how one of the disadvantages of online support groups is the communication of false information (Broom, 2005). Fear of giving false information may have influenced the men in this study to avoid giving medical information and instead utilize their own experiences and problem-solving strategies as sources of support.

The results of this study counter previous literature suggesting that men tend to avoid openly searching for support while being formal and secretive about their infertility-related problems (Kowalcek et al., 2001; Schmidt et al., 2005; Wallace, 1999). Discussions about the emotional journey associated with infertility occurred often on the ODBs and men provided both emotional support to convey empathy, understanding, and companionship, and appraisal support to normalize the range of feelings these men were experiencing. These findings confirm what has been observed in other research (Hanna & Gough, 2016a, 2016b; Malik & Coulson, 2008b) and does so using a relatively large sample of male and female posters. Typically, men tend to have difficulties asking for psychological support, especially if they feel guilty about being the source of a couple’s infertility (Jaoul et al., 2014; Petok, 2015). To this end, the empathetic responses from female supporters may have been a facilitating factor in helping men break away from traditional gender roles and openly request for support (Kiss & Meryn, 2001; Mo et al., 2009; Oliffe & Phillips, 2008; Schmidt, 2009). Although women online facilitate this exchange, it is not necessary for women to be present on ODBs for men to support one another emotionally (Hanna & Gough, 2016a, 2016b; Malik & Coulson, 2008b). Emotional support appears to have been beneficial for these men as many users explicitly stated how it made them feel less isolated, hopeless, and depressed to know they were not the only ones going through infertility. This buffering effect has been demonstrated in other studies of social support (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Malik & Coulson, 2008b).

The present study also supports previous work on the psychological impact of infertility suggesting that men want to take the role of the supportive partner and have to suppress their emotions to fulfill this position (Cousineau & Domar, 2007). As men using the ODBs often had their wives as their only confidantes, they felt that they had nowhere else to turn when confronted with adversity. Moreover, the issue of stigma was repeatedly discussed by these men. This was an important theme that emerged in the present study, where men explicitly discussed how their perception of the stigma associated with infertility negatively influenced their social interactions, inducing an avoidance to discuss the topic and an inability to acquire support in person. This further enhanced feelings of isolation and made them feel withdrawn from their wives and close relatives. As ODBs allow men to discuss their emotions openly and anonymously, these forums appear to be a safe and judgment free venue for men to express their emotions to individuals like themselves. This would in turn reduce the fear of social stigma, emasculation, and the burden of disclosing to relatives when seeking face-to-face support (Berger et al., 2005; Gannon et al., 2004; White & Dorman, 2001).

Within the messages, there were several instances where men mentioned they had nowhere else to go to share their emotions and discuss concerns regarding their relationships with their wives, friends, and family. Men also stated how they often felt that their wives blamed them for failed attempts at conceiving and that other family members were unreliable as support givers. Accordingly, ODBs appeared to be an alternate source of support for these men, which connected them to individuals who experienced similar hardships. As men may find it easier to disclose these issues anonymously, ODBs may be valuable in providing men with a broader and more accepting network of support (Broom, 2005; Hanna & Gough, 2016b; Martins, 2013).

As the literature on social support has linked successful advice giving to individuals with a shared understanding of the recipient’s situation (Albrecht & Adelman, 1984; Vayreda & Antaki, 2009; Wang et al., 2008), appraisal support from other men struggling with infertility was expected to be especially beneficial. Analyses of male-only ODBs for infertility indicate that men value support from other men with similar experiences of infertility (Hanna & Gough, 2016b). A major theme in this analysis was that men explicitly sought out appraisal support to acquire the perspective of other men with fertility problems to cope better with their own experience of infertility. Interestingly, although women attempted to assist men with issues specific to male factor infertility, their advice was less well-received than that of other men. It would appear that the men using these ODBs were looking for support from other men in similar circumstances. Consequently, if the support provider did not meet this requirement, the content of the support would not be as successful in validating their experience (Wang et al., 2008).

There are a number of limitations to the present study which must be considered. First, the extent to which the men who choose to use ODBs are representative of the general population of men having fertility problems still remains unclear. Second, due to the anonymous nature of these ODBs, it was not possible to accurately determine demographic characteristics of these users including ethnicity, age, educational level, and socioeconomic background. Third, the gender of users identified for this study was sometimes ambiguous and determined through their username, the type of infertility they were experiencing and/or the mention of gender in their public post history. As a result, gender differences in support provision was not examined. Fourth, although this study examined messages from two different support group communities, the results may have been influenced by the nature of the website chosen. The social networking website chosen was accessible internationally, all posts analysed on the infertility discussion boards were in English and both genders had access to view and answer messages. Future research should consider other websites or online media where social support can be delivered exclusively by men.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that through ODBs, men are able to discuss openly their experience of infertility and acquire various types of social support in response. This study reaffirms the role and importance of appraisal support as the primary method of online peer support communication. As depicted in the thematic analysis, appraisal support is critical in helping normalize the experiences of these men which may in turn reduce the stigma and social isolation associated with infertility. Supportive interventions should focus on reducing negative perceptions of infertility among men and facilitating the interaction between individuals with a shared experience of infertility. Having an available online peer support network appears to facilitate these exchanges by connecting men with fertility problems anonymously through a secure and accessible medium. As men are able to search for social support online and receive the assistance they desire, future studies should investigate which types of support are most beneficial in reducing stigma and social isolation, and whether in-person or online support groups are most effective in helping men cope with the negative consequences of infertility.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Stephanie Robins and Skye Miner for commenting on the earlier versions of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Team Grant: Boys’ and Men’s Health—Promoting Physical and Mental Health in Men Facing Fertility Issues funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR TE1-138296).

References

- Agostini F., Monti F., De Pascalis L., Paterlini M., La Sala G. B., Blickstein I. (2011). Psychosocial support for infertile couples during assisted reproductive technology treatment. Fertility and Sterility, 95, 707-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht T. L., Adelman M. B. (1984). Social support and life stress. Human Communication Research, 11, 3-32. [Google Scholar]

- Berger M., Wagner T. H., Baker L. C. (2005). Internet use and stigmatized illness. Social Science & Medicine, 61, 1821-1827. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. [Google Scholar]

- Broom A. (2005). Medical specialists’ accounts of the impact of the Internet on the doctor/patient relationship. Health (London), 9, 319-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnik T., Cook J. L., Yuzpe A. A., Tough S., Collins J. (2012). Estimating the prevalence of infertility in Canada. Human Reproduction, 27, 738-746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, & Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. (2014, December). Tri-council policy statement: Ethical conduct for research involving humans. Retrieved from http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/pdf/eng/tcps2-2014/TCPS_2_FINAL_Web.pdf

- Chandra A., Copen C. E., Stephen E. H. (2014). Infertility service use in the United States: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 1982-2010 (National Health Statistics Report). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr073.pdf [PubMed]

- Chen A. T. (2014). What’s in a virtual hug? A transdisciplinary review of methods in online health discussion forum research. Library & Information Science Research, 36, 120-130. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38, 300-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Wills T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310-357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau T. M., Domar A. D. (2007). Psychological impact of infertility. Best Practice & Research: Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 21, 293-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culley L., Hudson N., Lohan M. (2013). Where are all the men? The marginalization of men in social scientific research on infertility. Journal of Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 27, 225-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon R., Cumming C. E., Cumming D. C. (2000). Psychological well-being and coping patterns in infertile men. Fertility and Sterility, 74, 702-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer A. A., Quinton R., Morin D., Pitteloud N. (2014). Identifying the unmet health needs of patients with congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism using a web-based needs assessment: Implications for online interventions and peer-to-peer support. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 9, 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein Y. M., Rosenberg H. S., Grant T. V., Hemenway N. (2002). Use of the internet as the only outlet for talking about infertility. Fertility and Sterility, 78, 507-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M., Donelle L., Hume-Loveland L. (2012). Social support and online postpartum depression discussion groups: A content analysis. Patient Education and Counseling, 87, 405-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G., Till J. E. (2001). Ethical issues in qualitative research on internet communities. British Medical Journal, 323, 1103-1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon K., Glover L., Abel P. (2004). Masculinity, infertility, stigma and media reports. Social Science & Medicine, 59, 1169-1175. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greil A. L., Slauson-Blevins K., McQuillan J. (2010). The experience of infertility: A review of recent literature. Sociology of Health & Illness, 32, 140-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna E., Gough B. (2015). Experiencing male infertility. A review of the qualitative research literature, SAGE Open, 5(4). doi: 10.1177/2158244015610319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna E., Gough B. (2016. a). Emoting infertility online: A qualitative analysis of men’s forum posts. Health (London), 20, 363-382. doi: 10.1177/1363459316649765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna E., Gough B. (2016. b). Searching for help online: An analysis of peer-to-peer posts on a male-only infertility forum. Journal of Health Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1359105316644038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J., MacGuire P., Pitceathly C. (1995). Confiding in crisis: Gender differences in pattern of confiding among cancer patients. Social Science & Medicine, 41, 1255-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L., Kurinczuk J. J., Ziebland S. (2010). Infertility; isolation and the Internet: A qualitative interview study. Patient Education and Counseling, 81, 436-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaoul M., Bailly M., Albert M., Wainer R., Selva J., Boitrelle F. (2014). Identity suffering in infertile men. Basic and Clinical Andrology, 24, 1. doi: 10.1186/2051-4190-24-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N., Cassell C., Symon G. (2004). Using templates in the thematic analysis of texts. In Cassell C., Symon G. (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp. 256-270). London, England: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss A., Meryn S. (2001). Effect of sex and gender on psychosocial aspects of prostate and breast cancer. British Medical Journal, 323, 1055-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalcek I., Wihstutz N., Buhrow G., Diedrich K. (2001). Coping with male infertility: Gender differences. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 265, 131-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford C. P., Bowsher J., Maloney J. P., Lillis P. P. (1997). Social support: A conceptual analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25, 95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S. H., Coulson N. S. (2008. a). Computer-mediated infertility support groups: An exploratory study of online experiences. Journal of Patient Education and Counseling, 73, 105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S. H., Coulson N. S. (2008. b). The male experience of infertility: A thematic analysis of an online infertility support group bulletin board. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 26, 18-30. [Google Scholar]

- Malik S. H., Coulson N. S. (2010). Coping with infertility online: An examination of self-help mechanisms in an online infertility support group. Journal of Patient Education and Counseling, 81, 315-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S. H., Coulson N. S. (2011). A comparison of lurkers and posters within infertility online support groups. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 29, 564-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins M. V., Peterson B. D., Costa P., Costa M. E., Lund R., Schmidt L. (2013). Interactive effects of social support and disclosure on fertility-related stress. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(4), 371-388. [Google Scholar]

- Mo P. K., Malik S. H., Coulson N. S. (2009). Gender differences in computer-mediated communication: A systematic literature review of online health-related support groups. Journal of Patient Education and Counseling, 75, 16-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Phillips M. J. (2008). Men, depression and masculinities: A review and recommendations. Journal of Men’s Health, 5, 194-202. [Google Scholar]

- Owen J. E., Klapow J. C., Roth D. L., Tucker D. C. (2004). Use of the internet for information and support: Disclosure among persons with breast and prostate cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 27, 491-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B., Pirritano M., Christensen U., Schmidt L. (2008). The impact of partner coping in couples experiencing infertility. Human Reproduction, 23, 1128-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petok W. D. (2015). Infertility counseling (or the lack thereof) of the forgotten male partner. Fertility and Sterility, 104, 260-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt L. (2009). Social and psychological consequences of infertility and assisted reproduction: What are the research priorities? Human Fertility, 12, 14-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt L., Holstein B. E., Christensen U., Boivin J. (2005). Communication and coping as predictors of fertility problem stress: Cohort study of 816 participants who did not achieve a delivery after 12 months of fertility treatment. Human Reproduction, 20, 3248-3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker S. A., Brownell A. (1984). Toward a theory of social support: Closing conceptual gaps. Journal of Social Issues, 40(4), 11-36. [Google Scholar]

- Sillence E. (2013). Giving and receiving peer advice in an online breast cancer support group. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16, 480-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. F., Walsh T. J., Shindel A. W., Turek P. J., Wing H., Pasch L., . . . The Infertility Outcomes Program Project Group. (2009). Sexual, marital, and social impact of a man’s perceived infertility diagnosis. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6, 2505-2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithson J., Sharkey S., Hewis E., Jones R., Emmens T., Ford T., Owens C. (2011). Problem presentation and responses on an online forum for young people who self-harm. Discourse Studies, 13, 487-501. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen J., Collie K., McLeod D., Rojubally A., Fergus K., Speca M., . . . Elramly M. (2014). Talking with text: Communication in therapist-led, live chat cancer support groups. Journal of Social Science & Medicine, 104, 178-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwerker L. C., Prigerson H. G. (2004). Social support and technological connectedness as protective factors in bereavement. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 9, 45-57. [Google Scholar]

- Vayreda A., Antaki C. (2009). Social support and unsolicited advice in a bipolar disorder online forum. Qualitative Health Research, 19, 931-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace P. (1999). The psychology of the Internet. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Walther J. B., Pingree S., Hawkins R. P. (2008). Health information, credibility, homophily, and influence via the internet: Web sites versus discussion groups. Health Communication, 23, 358-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White M., Dorman S. M. (2001). Receiving social support online: Implications for health education. Health Education Research: Theory and Practice, 16, 693-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegers-Hochschild F., Adamson G. D., de Mouzon J., Ishihara O., Mansour R., Nygren K., . . . Vanderoel S. (2009). The international committee for monitoring assisted reproductive technology (ICMART) and the world health organization (WHO) revised glossary on ART terminology, 2009. Fertility and Sterility, 92, 1520-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]