Abstract

It is well-known that majority of smokers worldwide quit smoking without any assistance. This is even more evident among Chinese smokers. The aim of this qualitative study was to explore how Chinese Canadian immigrant men who smoked cigarettes perceived smoking cessation aids and services and how they used any form of the smoking cessation assistance to help them quit smoking. The study was conducted in British Columbia, Canada. Twenty-two Chinese immigrants were recruited by internet advertisement and through connections with local Chinese communities. Ten of the 22 participants were current smokers and the other 12 had quit smoking in the past 5 years. Data were collected using semistructured interviews. Although all participants, including both the ex-smokers and current smokers, had made more than one quit attempt, they rarely used cessation aids or services even after they had immigrated to Canada. The barriers to seeking the cessation assistance were grouped into two categories: practical barriers and cultural barriers. The practical barriers included “Lack of available information on smoking cessation assistance” and “Difficulty in accessing smoking cessation assistance,” while cultural barriers included “Denial of physiological addiction to nicotine,” “Mistrust in the effectiveness of smoking cessation assistance,” “Tendency of self-reliance in solving problems,” and “Concern of privacy revelation related to utilization of smoking cessation assistance.” The findings revealed Chinese immigrants’ unwillingness to use smoking cessation assistance as the result of vulnerability as immigrants and culturally cultivated masculinities of self-control and self-reliance.

Keywords: Chinese immigrants, smoking cessation, men’s health, culture, qualitative study

Introduction

Tobacco use is the single largest preventable cause of premature death worldwide, killing nearly 6 million people a year (World Health Organization [WHO], 2015). China has the largest number of smokers in the world, with one in every three smokers in the world being Chinese (WHO, 2015). Smoking in China is predominantly a male behavior, with more than half of Chinese adult men smoking while less than 3% of women smoke (WHO, 2015).

Researchers have reported that smokers who receive some forms of smoking cessations assistance are more likely to be successful in quitting smoking (Cahill, Stevens, Perera, & Lancaster, 2013; Ormston, van der Pol, Ludbrook, McConville, & Amos, 2015; Wenig, Erfurt, Kröger, & Nowak, 2013). A recent Cochrane review concluded that pharmacotherapy, including nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and other pharmacological aids, such as bupropion, varenicline, and cytisine, improve the chances of successful quit (Cahill et al., 2013). Smoking cessation services, such as self-help materials and telephone, individual and group counseling, have also been identified to increase odds of successful cessation (Hung, Dunlop, Perez, & Cotter, 2011; Levinson et al., 2008; Ormston et al., 2015; Wenig et al., 2013).

Globally, majority of smokers quit smoking without using any form of the smoking cessation assistance. For example, in the Western world, 60% to 80% of ex-smokers report quitting cold turkey or cutting down before eventually quitting without using cessation assistance (Chapman & MacKenzie, 2010; Kotz, Fidler, & West, 2011). Unassisted quitting is more evident with Asian smokers. Studies in Japan and South Korea have reported that less than 20% of smokers used cessation aids in their quitting attempts (Hagimoto, Nakamura, Morita, Masui, & Oshima, 2010; Shin et al., 2013). A large-scaled survey with 4,732 adult smokers in China reported that while 48.2% had received advice from physicians to quit smoking, only 5.6% had used pharmacotherapy (Jiang, Elton-Marshall, Fong, & Li, 2010). Little knowledge is available on whether or not the indifference of the Chinese smokers to smoking cessation assistance is related to the unavailability of the assistance or unwillingness of the smokers to use it.

A limited number of studies have reported lower smoking prevalence and higher quit rates among Chinese Canadian immigrants compared with the Canada-born citizens (Neligan, 2008; Newbold & Neligan, 2012). A study based on data from the 2001 Canadian Census reported a smoking rate of 10.2% among Chinese immigrants compared to a rate of 25.6% among the Canada-born; while smoking cessation odds ratio between the Chinese immigrants and Canada-born was 1.272 versus1 (Newbold & Neligan, 2012). However, little is known about the role of smoking cessation assistance in the quitting experiences of the Chinese immigrants.

Smoking is a gendered behavior, associated with gender identities, gender roles, and gender relationships (Bottorff et al., 2014; Everett, Bullock, Longo, Gage, & Madsen, 2007; Oliffe, Bottorff, & Sarbit, 2012). Men’s smoking is universally associated with gender expectations for men, signifying masculine ideals of independence, physical resilience to harmful substances, and capacity to endure risk taking (Everett et al., 2007; Oliffe et al., 2012; White, Oliffe, & Bottorff, 2012a). Masculinities are multidimensional, contested, and dynamic. As family breadwinners, men sometimes use smoking to cope with work-related stress and at the same time might be concerned with the economic burden on their family due to the cost of smoking; as protectors of their families, they might also be concerned about the health risks of second-hand smoke to nonsmokers in the family. While research in the West has associated decreased smoking among expectant and new fathers to masculine expectations and aspirations related to fatherhood (Everett et al., 2007; Oliffe et al., 2012; White et al., 2012a), little research has been done to explore the smoking patterns among Chinese fathers and the influence of masculine expectations related to being a father (Fu, Chen, Wang, Edwards, & Xu, 2008; Zheng et al., 2014).

In China, smoking has provided a strong positive signifier of masculinity and an important way to embody idealized notions of manhood and enact authority. As a culturally accepted practice, smoking is regarded as social currency and masculine capital (Ding & Hovell, 2012; Mao, Yang, Bottorff, & Sarbit, 2014). Smoking and cigarette gifting are an important component of men’s social interactions and business transactions, even among those residing in rural areas (Mao et al., 2014).

There is evidence, however, that masculine identities and roles change with immigration to another country. For example, researchers have reported enhanced masculinities among the immigrant men (Donaldson & Howson, 2009). For immigrant men, paid work represents a “key element” in maintaining masculine identities, particularly when the future of their family is challenged by the material instability caused by immigration. This is in stark contrast to the experiences of immigrant women who are usually expected to sacrifice their own careers and to be largely responsible for men’s physical and emotional well-being and for the unpaid care of their children, parents, and households (Donaldson & Howson, 2009).

A general reduction of smoking among Chinese immigrants in Western countries has been observed (S. Li, Kwon, Weerasinghe, Rey, & Trinh-Shevrin, 2013; Nakamura, Ialomiteanu, Rehm, & Fischer, 2011; Newbold & Neligan, 2012; Zhu, Wong, Tang, Shi, & Chen, 2007), and it is not clear whether the change is partially prompted by men’s role perceptions as the family provider and family protector. As masculinities are contextual, it is important to explore Chinese immigrants’ masculinities and their relations to the immigrants’ smoking.

This article originates from a study to explore the smoking behaviors of Chinese immigrant men after they became fathers (Mao, Bottorff, Oliffe, Sarbit, & Kelly, 2015). As part of the study, quit attempts were examined and the role of smoking cessation assistance was explored. This part formed the foundation for this article and reports on the attitudes of Canadian Chinese immigrant men who smoked toward smoking cessation assistance and factors influencing their use of cessation assistance to quit smoking.

The study was conducted in Canada, where a comprehensive range of tobacco control measures has been implemented (Health Canada, 2015). Smoking cessation aids are available in every province, with free NRT in some provinces, while in other provinces, the NRT is available for purchase in supermarkets and pharmacies without prescription (Health Canada, 2015). Training has been provided to health professionals in many provinces, and assessment of smoking status and brief advice on smoking cessation are encouraged as part of routine practice (Bodner, Rhodes, Miller, & Dean, 2012).

Method

A qualitative interpretive research approach was used in conducting the study. Using this approach, the focus was on meanings and understandings developed socially and experientially. As such, the aim was not to test hypotheses driven but to produce an in-depth understanding of Chinese immigrant men’s perspectives on smoking and the process of cessation as influenced by their personal experiences and the social context (Rowlands, 2005). The study was reviewed and approved by a university behavioral research ethics board.

Data Collection Procedures

Bilingual advertisements for recruitment were distributed to Chinese organizations in lower mainland in British Columbia, Canada, and put on Chinese online forums. The Chinese forums were parts of Chinese websites in Canada, covering various aspects of life. The websites were in Chinese language to serve Chinese Canadian immigrants. There were no restrictions to accessing these websites. It was free to put on advertisements in the forums, and the advertisements could be on the forums for months. People who were interested in the study contacted the research team by telephone or e-mail, and those eligible for the study were invited to participate in the study.

Study Sample

Men who responded to the recruitment ads were screened for eligibility. Criteria for eligibility included the following: (1) self-identified as a Chinese immigrant or a Chinese Canadian, (2) currently smoking or having quit smoking in the past 5 years, (3) having lived in Canada for at least half a year, and (4) currently expecting a child or having a child younger than 5 years of age. Twenty-two Chinese Canadian immigrant men recruited through the Chinese forums (n = 21) or through the Chinese organizations (n = 1) met study criteria and provided informed consent. Among the 22 participants, 12 came from Ontario, 8 from British Columbia, and 2 from Quebec, representing the 3 most populous provinces in Canada.

A variety of backgrounds in terms of demography and smoking patterns are represented in the study sample (see Table 1). All the men were the first-generation Chinese immigrants, with two moving to Canada before 18 years of age, while the others immigrated after age of 18. The two early immigrants identified their first language as English while the others identified Chinese as their first language.

Table 1.

Demographics and Smoking Patterns of the Study Participants.

| Age, years | 38 ± 5.0 (28-46) |

| Education | |

| Elementary school and below | 0 |

| Junior/middle school | 1 |

| High school | 0 |

| Nonuniversity (collage, vocational, technical, trade, etc.) | 3 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 13 |

| Master’s degree or over | 5 |

| Years in Canada | 8.7 ± 6.4 (0.5-22) |

| Occupation | |

| Clerical/administrative | 5 |

| Construction/manual labor | 7 |

| Technical/skilled/professional/trade | 7 |

| Unemployed (disabled, student) | 3 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 21 |

| Divorced | 1 |

| Amount smoked | |

| ≤10/day | 7 |

| 10-20/day | 3 |

| >20/day | 0 |

| Quit smoking | 12 |

Interview Protocol

Semistructured interviews were conducted via telephone with all the participants except one, with whom a face-to-face interview was conducted. A topic guide was used to facilitate the interviews. The sample questions related to utilization of smoking cessation assistance are in Table 2. Probes and follow-up questions were used to encourage the participants to elaborate their quitting experiences. Also, they were encouraged to compare the cessation aids and services between China and Canada, and share their perceptions of the different attitudes between Chinese and Canadians toward the various forms of cessation assistance. Masculinity and/or gender role and how these related to smoking cessation were explicitly explored. The interviews were conducted by the bilingual researcher (AM), lasting from ½ hour to 1½ hours. Two of the interviews were conducted in English while the other 20 were in Mandarin. Participants were also asked questions about their demographic characteristics and their smoking history. A supermarket voucher worth of CAD$50 was provided to the participants to acknowledge their contribution to the study.

Table 2.

The Interview Questions Related to Utilization of Cessation Assistance.

| • Would you please tell me something about your smoking? |

| • Which factors helped you quit smoking? |

| • Which factors prevented you from quitting smoking? |

| • How did you use the smoking cessation assistance in your attempts to quit smoking? Or why did you not want to use the cessation assistance? (If the smokers had never used any forms of cessation assistance) |

| • Based on your observation, are there differences in seeking cessation assistance between Chinese smokers and Canadian smokers? What do you think have caused the differences? |

Data Analysis

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. For those interviews in Mandarin, translation of the interviews from Chinese into English was conducted at the same time as transcription. A bilingual research assistant with Chinese and English proficiency translated and transcribed the interviews and the translations and transcriptions were checked by the bilingual researcher (AM).

Thematic analysis using constant comparison was conducted with the transcribed interviews (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). A coding framework was developed based on the readings of the first three interviews. The bilingual researcher and the other two experienced qualitative researchers independently hand coded the first three interviews. They reviewed the data line by line to identify important ideas and initial concepts relevant to the purpose of the study. The initial codes generated from the previous interviews were checked using constant comparison with the following interviews, leading to expansion and revision of the codes. Definitions for each code were established to facilitate independent coding. For example, the code “Patterns of smoking” was defined as “Any comments about when, where, why the participant smokes; the length of smoking; and beliefs about smoking and health.” After comparisons were made, the researchers refined the coding framework. The comparisons also acted as the achievement of intercoder agreement, in which the three coders compared the names of the codes, frequency of the individual codes, and the coded segment in the data set.

Once the coding framework became stable, which meant no more modifications with the framework, the qualitative data management program Nvivo 8 was used to code and retrieve data. Codes were grouped to categories and were reviewed in detail, comparing and contrasting data from all participants to identify the factors to influence the smokers’ efforts to quit smoking. The three researchers reviewed and debated discordant narratives to reach consensus on the interpretation of the findings. Repeated narratives about the participants’ smoking and quitting experiences were evident and indicated that data saturation was achieved.

Results

All the participants had at least one child younger than 5 years old. Their average age was 38 ± 5.0 (range = 28-46 years). They had lived in Canada for 8.7 ± 6.4 years (range = 0.5-22 years), indicating that they were relatively new immigrants. All the 22 participants were smoking at the time they immigrated to Canada. By the time this study was implemented, 12 of them had quit smoking (defined as having stopped smoking for at least 1 week) while the other 10 were still smoking. All the current smokers were smoking less than they had before. The quit or reduction of smoking was prompted by two life events: moving to Canada and/or becoming a father. Both ex-smokers and current smokers had made more than one quit attempt. In general, men in this study made 2.7 ± 0.9 quit attempts (range = 2-5).

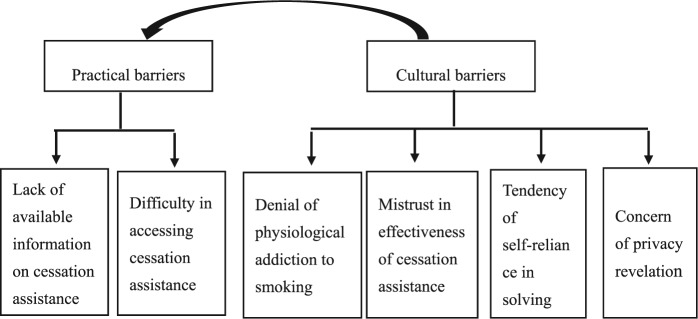

Only three of the participants reported using certain form of cessation assistance in their quit efforts, with one using E-cigarettes and the other two getting advice from physicians. The barriers that prevented the participants from using cessation assistance can be divided into two categories: practical barriers and cultural barriers. Although the men pointed to practical barriers, overall they were indifferent to cessation aids and services even when the aids and services were available, indicating that cultural barriers may be the most influential factor in preventing the participants from seeking cessation assistance (Figure 1). The following section will detail these barriers. The Chinese immigrant participants who smoked were coded as “CS,” and they were numbered according to the sequence they entered the study.

Figure 1.

The barriers preventing Chinese smokers from seeking smoking cessation assistance.

Practical Barriers

Lack of Available Information on Smoking Cessation Assistance

More than half of the participants acknowledged that they did not know whether or not smoking cessation aids or services were available in Canada because they did not intentionally seek such information. One participant (CS6), who had been in Canada for 4 years and currently smoking 15 cigarettes a day, said, “There might be some forms of cessation assistance in Canada. I did not care about them so I might have missed the relevant information.” However, about two thirds of the participants complained that they were never informed of the cessation aids and services available. A current smoker (CS4), who had lived in Canada the longest time (22 years) among all of the Chinese participants, complained about his lack of awareness of cessation assistance when he tried to quit smoking during his wife’s pregnancy, “I knew there were associations or organizations to help people to stop smoking. I had no connection to them. Nobody referred me to them. No one told me how to get there.” While the men did not actively seek information on cessation assistance, it also appeared that even if they were aware of cessation assistance they lacked information about how to access it.

Although becoming an expectant or new father has been associated with efforts to reduce and quit smoking (Everett et al., 2007; Fu et al., 2008; Oliffe et al., 2012; White et al., 2012a; Zheng et al., 2014), about half of the participants articulated that they did not get cessation help from the physicians during their wives’ pregnancy. One ex-smoker (CS8) had quit smoking for 1.5 years due to concerns about the impact of his smoking on his pregnant wife as well as constraints on smoking in Canada related to policies and social norms that denormalize smoking. He recalled their physician’s neglect of the issue of his smoking when he accompanied his wife for regular obstetric checkups, “They just talked with my wife. They did not have any impact on my smoking.”

Despite feeling neglected by physicians, all the Chinese participants spoke highly of the important role of physicians to smokers’ successful quit. One man (CS9), who quit smoking as soon as he knew of his wife’s pregnancy, explained, “Yea, I did [quit]. My family doctor told me that if the pregnant woman inhales second hand smoke, it will affect the fetus. So the advice from family doctors was important.”

Difficulty in Accessing Smoking Cessation Assistance

Most of the study participants did not know whether or not there were counseling services or cessation programs provided for them. However, they stated that even if there were such services it was impractical for them to attend because they had no time for such activities. As first-generation immigrants, the participants described difficulties in earning a living in Canada. For example, one current smoker who worked in a Chinese restaurant claimed that he could not afford the time to accompany his wife to the obstetric clinic: “You have to wait for an hour for the doctor, and we Chinese won’t have that time.” Here he used “we Chinese” suggesting that being busy with earning a living was not only his single experience but the experience of many Chinese immigrant men.

Language barrier also prevented the participants from accessing cessation assistance. Among the 22 study participants, 18 had baccalaureate degrees or higher, and they could read, write, listen, and speak English. Yet they preferred materials or services in Chinese to those in English, “If the quitlines don’t provide services in Chinese, I don’t think Chinese would want to use them,” said CS8, an ex-smoker who quit smoking unassisted 1 year and 5 months ago.

Cultural Barriers

Denial of Physiological Addiction to Smoking

The study participants all claimed that they did not need cessation assistance because they were not addicted to cigarette smoking. According to the participants, smoking was only a habit they had difficulty giving up. The participants, sometimes reluctantly, confessed that they were addicted to the “habit of smoking” after they reflected on the reason that they could not quit after several quit attempts.

There seemed a line between physiological addiction and psychological addiction to tobacco smoking: the physiological addicts could not leave smoking while the psychological addicts could do without. The participants tended to acknowledge the possibility of a psychological addiction after they initially denied any addiction:

For my case, I was not heavily addicted to cigarettes. I didn’t need them [nicotine replacement products]. Once I made up my mind to stop smoking I stopped. (CS12, ex-smoker)

No, I have never thought of seeking help. The nicotine replacement stuff helps you to quit smoking, by reducing your addiction to nicotine physiologically. But I think cutting psychological addiction is the key to quitting. (CS7, current smoker)

Their denial of physiological addiction to smoking influenced their interest in seeking cessation assistance. According to the participants, NRT was useful for smokers who were physiologically addicted to cigarettes. Light smokers reasoned that since they were addicted solely psychologically, NRT could not help them. On the other hand, they believed heavy smokers were addicted both physiologically and psychologically, so NRT could help them to a certain degree but not completely. Willpower was perceived to be the key element to successful cessation for both light smokers and heavy smokers.

The men also compared their tobacco smoking to addiction to other substances, in order to support their claims that they were not physiologically addicted to smoking. CS11, a 40-year-old current smoker who had smoked for more than 15 years and had reduced his smoking from 2 or 3 days a pack (20 cigarettes/pack) to the current level of fewer than 10 cigarettes per week, denied his addiction to smoking. He stated, “We are 30’s or 40’s grown-up adults already. We just smoke a little bit every day. Smoking cigarette is not the same as taking drugs. We are not alcoholics who can’t live a day without drinking.” According to this smoker, a grown-up man should be able to exercise self-control with his smoking, which means he was able to avoid impulses to smoke and behave in line with social norms, that is, to not smoke obsessively or in the places where smoking was inappropriate or not permitted. His success in substantially reducing his smoking was viewed as a demonstration of his capacity for self-control. Although the study participants rarely used NRT, they expressed cynicism about NRT that directly contrasted with perceptions of Canadians’ enthusiasm for this cessation aid, “I heard lots of Canadians tried NRT. Actually Canadians act in a rigid way. Is the NRT really useful?” (CS14, current smoker)

Mistrust in the Effectiveness of Smoking Cessation Assistance

Several smokers, based on their own experiences and experiences of the people around them, believed in the short-term, rather than long-term, effectiveness of smoking cessation assistance. One man, who used to smoke 15 cigarettes a day and quit smoking 2 years ago via “cold turkey” (CS15), described his friend’s quitting experiences using NRT. He stated,

One of my friends tried one product. He put something on his arm. I don’t know what that was. But it was only useful when he put it on arm. Once he took it off, there was no effect at all.

CS15 attributed taking up regular jogging and walking, rather than using cessation assistance, as key to his success in quitting and remaining smoking-free.

While the participants viewed NRT as ineffective, they further doubted the effectiveness of cessation counseling services. Only one man in the sample reported having had the experience of a counseling session, and although it was not for smoking cessation, his experience reflected the view that counseling was sought to solve problems:

I once came across difficulties and I went to a Canadian organization. They talked and talked and talked but all the talkings were useless to solve my problem. Their counseling might be helpful for some people who needed comfort because of distress. But I went there not for being comforted. I needed to solve the problem. (CS21, ex-smoker)

While the purpose of the counseling is generally to enhance the coping capacity and self-efficacy for the help-seekers, the participants expected counseling as a way to solve the underlying problems of help seekers. Similarly, the study participants did not see the usefulness of quitline services, as CS15, who quit smoking unassisted 2 years ago expressed his opinion on the quitlines, “You are so thirsty for a cigarette and you want a cigarette; you make a phone call to the quitline. They can’t solve this problem for you.”

Tendency of Self-Reliance in Solving Problems

Some of the study participants observed that Canadians were more likely to seek help from governments and other institutions, while Chinese tended to solve problems by their own.

Here people are told from early childhood that you can go to governments for help if you come across any problems. Chinese are told to solve their personal problems within their own resources. (CS14, current smoker)

According to the participants, there was a culture of self-reliance among them and one of help-seeking among Canadians. The difference was deeply rooted in the environment one grew up in and influenced attitudes toward smoking cessation assistance. One man explained,

They (the Canadians) like to go see psychologists. Chinese do not have this kind of values yet. I guess people will laugh at you if you go to a counselor for quitting smoking. (CS5, current smoker)

Concern of Privacy Revelation Related to Utilization of Smoking Cessation Assistance

There were concerns about perceived risks related to sharing private information with others when seeking smoking cessation assistance. CS19, an ex-smoker who quit smoking because of concerns of health risks of his smoking to his son and his pregnant wife, explained why he did not seek cessation assistance: “I also think that smoking is a very personal thing so I do not like to share it with other people.” Another participant, CS9, who quit smoking as soon as his wife became pregnant, disagreed that smoking was a personal issue and was not concerned about sharing information about his smoking behaviors with others, even with strangers, because there were “lots of people” who smoked in Canada as well as in China. However, he agreed that in seeking cessation assistance there could be a risk of revealing private family matters. He explained, “Smoking is not (private), but things like fighting with your wife is private. You will not reveal that information.” As a result, the Chinese immigrant smokers were cautious about attending group sessions focused on smoking cessation:

Quit smoking group? Canadians may like to join it. We Chinese don’t want to reveal our privacy. But on the other hand, Canadians also pay much attention to protect their privacy. I don’t know how to express my meaning. But definitely I don’t want to join a quit group. (CS17, current smoker)

Concerns about privacy were also related to the “closeness” of the Chinese immigrant community in Canada, as one of the participants who had lived in Canada for 4 years, said:

You see every year more Chinese are coming to Canada. But still we Chinese are an ethnic minority in Canada. I find that the Chinese immigrants, even when they have lived in Canada for many years, don’t like to join the Canadian groups in community activities. Chinese immigrants like to be with fellow Chinese. If you live in a small city in Canada, you may know all the Chinese in your city. (CS6, current smoker)

While these close connections in the Chinese community provided an important source of support for Chinese immigrants, along with this came a potential risk to privacy revelation. The fact that 21 of the 22 participants were recruited through the Chinese online forums with only one through personal connections may be a reflection of Chinese immigrants’ attention to privacy protection. Online forum provided men with an acceptable degree of anonymity.

The Chinese men were clear that completely quitting smoking was a tough and lengthy process and that failure to quit might often happen. However, men worried that failure in front of outside people would result in them “losing face.” One ex-smoker (CS21) who quit smoking 3 months after he immigrated to Canada due to the changed smoking environment in Canada, said, “If you and others discuss quitting smoking and you boast that you are able to quit if you want; then you smoke again, how will they look at you? You surely don’t have face.” Some participants mentioned that they would rather go online to discuss quitting than go to a person or a group in real life to discuss quitting. Indeed there were three participants who sought online information on smoking cessation before or during their quitting smoking.

Discussion

It may be self-evident that immigrant smokers encounter difficulty in accessing health services in the host country due to language barriers and unfamiliarity with these services. Studies have reported that immigrants, particularly new immigrants, experienced delay or neglect in seeking health assistance (Beiser & Hou, 2014; Parikh, Fahs, Shelley, & Yerneni, 2009; Singh, Rodriguez-Lainz, & Kogan, 2013). The findings of this study suggest that the interplay between practical and cultural barriers profoundly influenced Chinese immigrant men’s utilization of smoking cessation assistance. The Chinese immigrant smokers were unaware of cessation aids and services available in Canada, not because these forms of assistance did not exist but because the men had no interest in seeking the assistance.

An interesting finding is that the Chinese male smokers drew a line between physiological addiction and psychological addiction to cigarette smoking. Based on their perception, psychological addiction was controllable while physiological addiction was uncontrollable. The overall tendency of the Chinese men to deny (physiological) addiction may be related to Chinese men’s tendency to portrait themselves able to control their health behaviors (Jiang et al., 2010). Although acknowledging their psychological addiction to smoking, the Chinese smokers showed indifference to smoking cessation services, like counseling, helplines, group support, and so on. Previous research has identified that since medical treatments are viewed as acceptable among Asian men, treatments for addiction that simultaneously address medical and emotional problems are more likely to be taken up than solely psychosocial support (Fong & Tsuang, 2007).

The finding of this study that the smokers believed in willpower as the key for successful quit symbolizes masculine norms of strength and self-control for men in all cultures (Everett et al., 2007; Oliffe et al., 2012; White et al., 2012a). However, the cynicism the Chinese men showed to Canadian men’s help-seeking behavior sheds light on important variations in the way masculinities are practiced in different cultures. Chinese men’s masculinity is rooted in Chinese culture, which honors gender identities for men as the head of their society and their family (C. Li, 2000; Mao, Bristow, & Robinson, 2013). Chinese male images are portrayed as tough, fearless, and resistant in a patriarchal society, and these traits have been enhanced as the result of immigration. Also, Chinese people’s self-concept is embedded (C. Li, 2000). In a sense, Chinese men’s masculinity is incorporated with familism and collectivism (C. Li, 2000; Mao et al., 2013).

Researchers have reported that people’s behaviors are related to in-group/out-group orientations constructed by collectivistic culture and individualistic culture (Balliet, Wu, & De Dreu, 2014; Stephan, Stephan, Saito, & Barnett, 1998). An in-group in collectivistic cultures is represented by one’s family, friends, and other people concerned with one’s welfare; while in individualistic cultures the in-group is defined as people who are similar to oneself in social class, race, beliefs, attitudes, and values. So in-groups in individualistic culture cover a much broader spectrum than in collectivistic culture but the members of in-groups in collectivistic culture are more closely bounded. That may explain why Chinese men were cautious not to overly seek the smoking cessation assistance provided by out-groups. In collectivistic culture, protecting each other’s face is key to keep in-group harmony (Balliet et al., 2014; Stephan et al., 1998). The fact that some of the Chinese smokers showed interest in online information on smoking cessation indicated that Chinese immigrants were also trying to use available resources. However, they were careful in seeking the appropriate resources due to concerns about privacy and perceived risks related to “losing face” and jeopardizing family reputation to out-groups.

Policy Implications

The practical barriers clearly points to the need for support from governmental and nongovernmental organizations for Chinese immigrant smokers to quit smoking. Research should be conducted with Chinese immigrants to explore the kinds of messages that will motivate them to quit smoking and how to appropriately deliver the messages to the enlarging Chinese communities (Canada Immigration Newsletter, 2014). English language services, such as English versions of materials on smoking cessation or quitline services in Chinese, should be provided for Chinese immigrants.

Addressing cultural barriers is also important because these barriers fundamentally affect men’s help-seeking behaviors. Researchers have suggested that smoking cessation interventions for men should be in line with masculine ideals (White, Oliffe, & Bottorff, 2012b). While Chinese men’s determination and perceived self-efficacy for cessation should be acknowledged, they should also be provided information about the greater chances of success for quitting smoking with cessation assistance so that they can make an informed decision.

Despite distrust in psychosocial counseling and other counseling services, the Chinese immigrant men who smoked, like those male smokers in China, expressed trust in physicians’ advice (Lin, Zhao, Cheng, & Lam, 2013; Yu et al., 2004). Researchers have identified pregnancy as a “teachable moment” for expectant parents to quit smoking (McBride, Emmons, & Lipkus, 2003). The “teachable moment” is defined as a naturally occurring event or life transition that influences one’s readiness for learning new information and changing behaviors (McBride et al., 2003). This study identified that immigrant Chinese men’s interests in smoking cessation elevated during their wives’ pregnancy. However, the physicians seemed to have missed the opportunity to provide cessation help to the expectant fathers, simply because Chinese women were usually the nonsmokers. Brief advice from physicians has been reported to have a significant influence on smoking cessation (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). In future the obstetric physicians and/or family doctors in Canada should assess the partner smoking status when they serve Chinese immigrant women and provide male smokers with information and referral to cessation services.

Other forms of smoking cessation assistance, such as self-help materials and online messages, should be developed in line with the busy life of Chinese immigrants and their needs to protect privacy. Recent findings have supported effectiveness of Web-based interventions in tobacco control (Balhara & Verma, 2014; Brunette et al., 2015). Web-based interventions can reach a large section of the population at low cost. Also, the users of the online resources can access information at a pace and time of their own convenience. More research is needed to develop Web-based interventions specifically for Chinese men who smoke.

Limitations of the Study

As with all qualitative research, caution is needed to generalize the findings in this study due to the small number of participants. Also, the recruitment method (mainly through Chinese online forums) produced a cohort of mainly new immigrants. Their experiences in quitting smoking may be different from the long-term immigrants or the second-generation Chinese immigrants because the latter are likely able to access more social resources due to their language advantage and wider social connections. Despite these limitations, this study, as the first to explore Chinese Canadian immigrants’ experiences in seeking cessation assistance, provided in-depth explanations to the common findings that Chinese smokers usually quit smoking unassisted.

Conclusions

Chinese immigrant smokers tend to rely on their willpower as the only tool to quit smoking, even when exposed to an environment with cessation aids and services. A gender-based analysis identified Chinese men’s stronger tendency to be self-reliant in quitting smoking than Canadian men due to culturally cultivated masculinities. While institutional efforts are needed to overcome practical barriers, the key is to work with the masculinities of Chinese immigrant men to enhance their capacity in making informed decision to increase the chances of successful quitting in their own ways.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely thanks Joan Bottorff, John Oliffe, and Gayl Sarbit for their constructive guidance in conducting the study. The author also thanks Sharon Pan for her contribution in interview transcriptions and translations.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research study was made possible by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant No. 62R43745) and a postdoctoral fellowship award from the Psychosocial Oncology Research Training program.

References

- Balhara Y. P. S., Verma R. (2014). A review of web based interventions for managing tobacco use. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 36, 226-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balliet D., Wu J., De Dreu C. K. (2014). Ingroup favoritism in cooperation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 1556-1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiser M., Hou F. (2014). Chronic health conditions, labour market participation and resource consumption among immigrant and native-born residents of Canada. International Journal of Public Health, 59, 541-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodner M. E., Rhodes R. E., Miller W. C., Dean E. (2012). Smoking cessation and counseling: Practices of Canadian physical therapists. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(1), 67-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff J. L., Haines-Saah R., Kelly M. T., Oliffe J. L., Torchalla I., Poole N., . . . Phillips J. C. (2014). Gender, smoking and tobacco reduction and cessation: A scoping review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 13(1), 114. doi: 10.1186/s12939-014-0114-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunette M. F., Gunn W., Alvarez H., Finn P. C., Geiger P., Ferron J. C., McHugo G. J. (2015). A pre-post pilot study of a brief, web-based intervention to engage disadvantaged smokers into cessation treatment. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 10, 3. doi: 10.1186/s13722-015-0026-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill K., Stevens S., Perera R., Lancaster T. (2013). Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: An overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, (5), CD009329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canada Immigration Newsletter. (2014). The story of Chinese immigration to Canada. Retrieved from http://www.cicnews.com/2014/03/story-chinese-immigration-canada-033259.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Health-care provider screening for tobacco smoking and advice to quit: 17 countries, 2008-2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62, 920-927. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman S., MacKenzie R. (2010). The global research neglect of unassisted smoking cessation: Causes and consequences. PLoS Medicine, 7, e1000216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D., Hovell M. F. (2012). Cigarettes, social reinforcement, and culture: A commentary on “tobacco as a social currency: Cigarette gifting and sharing in China.” Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 14, 255-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson M., Howson R. (2009). Men, migration and hegemonic masculinity. In Donaldson M., Hibbins R., Howson R., Pease B. (Eds.), Migrant men: Critical studies of masculinities and the migration experience (pp. 210-217). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Everett K. D., Bullock L., Longo D. R., Gage J., Madsen R. (2007). Men’s tobacco and alcohol use during and after pregnancy. American Journal of Men’s Health, 1, 317-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong T. W., Tsuang J. (2007). Asian-Americans, addictions, and barriers to treatment. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 4(11), 51-59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C., Chen Y., Wang T., Edwards N., Xu B. (2008). Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in Chinese new mothers decreased during pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61, 1182-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagimoto A., Nakamura M., Morita T., Masui S., Oshima A. (2010). Smoking cessation patterns and predictors of quitting smoking among the Japanese general population: A 1-year follow-up study. Addiction, 105, 164-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. (2015). Strong foundation, renewed focus: An overview of Canada’s Federal Tobacco Control Strategy 2012-17. Retrieved from http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/pubs/tobac-tabac/fs-sf/index-eng.php

- Hung W. T., Dunlop S. M., Perez D., Cotter T. (2011). Use and perceived helpfulness of smoking cessation methods: Results from a population survey of recent quitters. BMC Public Health, 11, 592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Elton-Marshall T., Fong G. T., Li Q. (2010). Quitting smoking in China: Findings from the ITC China Survey. Tobacco Control, 19(Suppl. 2), i12-i17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotz D., Fidler J. A., West R. (2011). Did the introduction of varenicline in England substitute for or add to the use of other smoking cessation medications? Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 13, 793-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson A. H., Glasgow R. E., Gaglio B., Smith T. L., Cahoon J, Marcus A. C. (2008). Tailored behavioral support for smoking reduction: Development and pilot results of an innovative intervention. Health Education Research, 23, 335-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. (2000). The sage and the second sex: Confucianism, ethics, and gender. Chicago, IL: Open Court. [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Kwon S. C., Weerasinghe I., Rey M. J., Trinh-Shevrin C. (2013). Smoking among Asian Americans: Acculturation and gender in the context of tobacco control policies in New York City. Health Promotion Practice, 14(5 Suppl.), 18S-28S. doi: 10.1177/1524839913485757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P. R., Zhao Z. W., Cheng K. K., Lam T. H. (2013). The effect of physician’s 30s smoking cessation intervention for male medical outpatients: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Public Health (Oxford), 35, 375-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao A., Bottorff J. L., Oliffe J. L., Sarbit G., Kelly M. T. (2015). A qualitative study of Chinese Canadian fathers’ smoking behaviors: Intersecting cultures and masculinities. BMC Public Health, 15, 286. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1646-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao A., Bristow K., Robinson J. (2013). Caught in a dilemma: Why do non-smoking women in China support the smoking behaviors of men in their families? Health Education Research, 28, 153-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao A., Yang T., Bottorff J. L., Sarbit G. (2014). Personal and social determinants sustaining smoking practices in rural China: A qualitative study. International Journal for Equity in Health, 13, 12. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-13-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride C. M., Emmons K. M., Lipkus I. M. (2003). Understanding the potential of teachable moments: The case of smoking cessation. Health Education Research, 18, 156-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N., Ialomiteanu A., Rehm J., Fischer B. (2011). Prevalence and characteristics of substance use among Chinese and South Asians in Canada. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 10(1), 39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neligan D. (2008). Smoking prevalence and cessation amongst immigrants in Canada (Unpublished master’s thesis). McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Newbold K. B., Neligan D. (2012). Disaggregating Canadian immigrant smoking behavior by country of birth. Social Science & Medicine, 75, 997-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Bottorff J. L., Sarbit G. (2012). Supporting fathers’ efforts to be smoke-free: Program principles. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 44(3), 64-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormston R., van der Pol M., Ludbrook A., McConville S., Amos A. (2015). Quit4u: The effectiveness of combining behavioral support, pharmacotherapy and financial incentives to support smoking cessation. Health Education Research, 30, 121-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh N. S., Fahs M. C., Shelley D., Yerneni R. (2009). Health behaviors of older Chinese adults living in New York City. Journal of Community Health, 34(1), 6-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands B. (2005). Grounded in practice: Using interpretive research to build theory. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methodology, 3(1), 81-92. [Google Scholar]

- Shin D. W., Suh B., Chun S., Cho J., Yoo S. H., Kim S. J., . . . Cho B. (2013). The prevalence of and factors associated with the use of smoking cessation medication in Korea: Trend between 2005-2011. PLoS One, 8(10), e74904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G. K., Rodriguez-Lainz A., Kogan M. D. (2013). Immigrant health inequalities in the United States: Use of eight major national data systems. Scientific World Journal, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/512313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan C. W., Stephan W. G., Saito I., Barnett S. M. (1998). Emotional expression in Japan and the United States: The nonmonolithic nature of individualism and collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29, 728-748. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. C., Corbin J. M. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedure for developing Grounded Theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Wenig J. R., Erfurt L., Kröger C. B., Nowak D. (2013). Smoking cessation in groups: Who benefits in the long term? Health Education Research, 28, 869-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C., Oliffe J. L., Bottorff J. L. (2012. a). Fatherhood, smoking, and secondhand smoke in North America: An historical analysis with a view to contemporary practice. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6, 146-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C., Oliffe J. L., Bottorff J. L. (2012. b). From the physician to the Marlboro man: Masculinity, health, and cigarette advertising in America, 1946-1964. Men and Masculinities, 15, 526-547. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2015). Tobacco in China. Retrieved from http://www.wpro.who.int/china/mediacentre/factsheets/tobacco/en/

- Yu D. K., Wu K. K., Abdullah A. S., Chai S. C., Chai S. B., Chau K. Y., . . . Yam H. K. (2004). Smoking cessation among Hong Kong Chinese smokers attending hospital as outpatients: Impact of doctors’ advice, successful quitting and intention to quit. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 16, 115-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P., Kegler M. C., Berg C. J., Fu W., Wang J., Zhou X., . . . Fu H. (2014). Correlates of smoke-free home policies in Shanghai, China. Biomed Research International. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1155/2014/249534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S. H., Wong S., Tang H., Shi C. W., Chen M. S. (2007). High quit ratio among Asian immigrants in California: Implications for population tobacco cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 9(Suppl. 3), S505-S514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]