Abstract

This study examined the role of media influence and immigration on body image among Pakistani men. Attitudes toward the body were compared between those living in Pakistan (n = 56) and those who had immigrated to the United Arab Emirates (n = 58). Results of a factorial analysis of variance demonstrated a significant main effect of immigrant status. Pakistani men living in the United Arab Emirates displayed poorer body image than those in the Pakistan sample. Results also indicated a second main effect of media influence.Those highly influenced by the media displayed poorer body image. No interaction effect was observed between immigrant status and media influence on body image. These findings suggest that media influence and immigration are among important risk factors for the development of negative body image among non-Western men. Interventions designed to address the negative effects of the media and immigration may be effective at reducing body image disorders and other related health problems in this population.

Keywords: body image, media influence, immigration, men, UAE, Pakistan

Introduction

Body image is a multidimensional construct, comprising of feelings, thoughts, and perceptions that individuals hold toward their body (Cash & Henry, 1995). These beliefs may be negative (Willet, 2007), and body image concerns can develop when there is a discrepancy between the actual and ideal body size, weight, or shape. Self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987, 1989) purports that emotional vulnerabilities result from inability to possess a desired goal, in this case, a “perfect” body. Those with negative attitudes toward their body may view it differently from reality, or hold the perception that their body does not meet societal standards (Primus, 2014). Cash (2004) suggested that self-perception of physical appearance is more powerful than the objective reality of appearance. Negative feelings or attitudes toward one’s physical appearance can have adverse effects on physical and mental health (Olivardia, Pope, Borowiecki, & Cohane, 2004), and are partly responsible for the development of bulimia, anorexia, low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, and obsessive–compulsive disorder in both men and women (Derenne & Beresin, 2006; McCreary & Saucier, 2009; Stice, 2002).

Body image dissatisfaction is commonly associated with women living in Western societies (Ferguson, 2013) and most past research in this field has assessed this population (Kennedy, Templeton, Gandhi, & Gorzalka, 2004; McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2004). A comparatively smaller body of research identifies that this issue is also becoming increasingly common among men (Barlett, Vowels, & Saucier, 2008; Dakanalis et al., 2015; Garner, 1997; Stapleton, McIntyre, & Bannatyne, 2016). Unfortunately, males may not disclose their body dissatisfaction because of the stereotype that it is a female-related disorder (Garner, 1997; Primus, 2014); they can therefore suffer in silence and develop related health problems (H. G. Pope, Phillips, & Olivardia, 2000). Body image dissatisfaction among men is a serious issue that should not be neglected because it can present problems of clinical significance (Cash, 2004; Cummins & Lehman, 2007). Blashill and Wilhelm (2014) reported that body distortion, associated with low self-esteem and depression among adolescent boys, persisted into adulthood. In addition, men who are dissatisfied with their bodies may also develop muscle dysmorphia (Grieve, 2007; Maida & Armstrong, 2005) which can affect their social and personal lives (H. G. Pope et al., 2000). Men with muscle dysmorphia are more likely to engage in substance abuse, including the use of steroids, and to attempt suicide (C. G. Pope et al., 2005).

Evidence suggests that body dissatisfaction among men differs from that of women (McCreary, Hildebrandt, Heinberg, Boroughs, & Thompson, 2007); therefore, the findings from studies conducted on women cannot be generalized to men (Adams, Turner, & Bucks, 2005). Women who are dissatisfied with their bodies usually internalize thin-ideals and adopt weight loss strategies (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2001; Thompson & Stice, 2001). Men with negative body image have been regarded as falling into two categories—those who want to gain weight and muscle mass, and those who want to lose weight (Drewnowski & Yee, 1987; McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2001). The category to which individuals belong may change over the life course. Younger males with negative body image may want to lose weight or gain weight. However, the desire for weight loss increases with age (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2003, 2004; McCreary & Sasse, 2000). How body image dissatisfaction influences behavior may also differ between the sexes. Men typically exercise to stay lean and build muscle, while women are more likely to diet to lose weight (Brunson, Øverup, Nguyen, Novak, & Smith, 2014; Drewnowski & Yee, 1987).

Body image, although an internal process, can be influenced by many external factors such as societal, familial, and peer pressure (Lefkowich, Oliffe, Clarke, & Hannan-Leith, 2017; McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2001; Tsiantas & King, 2001). Evidence suggests that exposure to mass media is among the major risk factors for body dissatisfaction among both men and women (Bardone-Cone, Cass, & Ford, 2008; Barlett et al., 2008; Bruns & Carter, 2015; Derenne & Beresin, 2006; McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2003). The increase in cases of body dissatisfaction among men in recent years has been suggested to stem from the growing importance placed by the media on the male physique (H. G. Pope et al., 2000).

By looking at trends within advertising it can be assessed why body dissatisfaction increased among men. H. G. Pope, Olivardia, Borowiecki, and Cohane (2001) conducted a survey of women’s magazines published between 1958 and 1998 and reported that the rate of women exposing their bodies remained the same over this period, while the rate of men exposing their bodies had increased from 3% in 1958 to 30% in 1998. Another trend was observed in that men were exposing their bodies when advertising unrelated products such as telephones and electronics. Fitness magazines increasingly feature more muscular models (Frederick, Fessler, & Haselton, 2005; Law & Labre, 2002) and the male body is depicted in sports magazines as an object. Instead of focusing on functional attributes of sportsmen, the media instead emphasizes their aesthetic attributes (Farquhar & Wasylkiw, 2007). Furthermore, the standards for the male body are becoming increasingly mesomorphic. Leit, Pope, and Gray (2001) examined male models in Playgirl magazines that were issued from 1973 to 1997 and concluded that male models have become more muscular over time. Action figures that are designed for boys have also changed in recent decades. The physical dimensions of current action figures have become larger and more muscular than their original designs (Baghurst, Hollander, Nardella, & Haff, 2006; H. G. Pope, Olivardia, Gruber, & Borowiecki, 1999). Consequently, males may be exposed to this ideal from an early age.

As with females, the rise in body image concerns among men can be partially explained by social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954) in which upward comparison results in negative self-evaluation. In contemporary society, upward comparison takes place when men internalize appearance ideals when they are constantly exposed to media showing current archetypes of bodily success—celebrities, athletes, and actors portraying the ultimate male as muscular and lean, an ideal which is not always achievable (H. G. Pope et al., 2001). Men who read fitness magazines developed more eating disorders and body dissatisfaction than those who did not read the magazines (Morry & Staska, 2001). Exposure to the idealized “male form,” as represented by the media, may result in body dissatisfaction (Arbour & Martin Ginis, 2006; Cahill & Mussap, 2007; Hargreaves & Tiggemann, 2009), and this can occur with only short-term contact with such representations (Baird & Grieve, 2006; Mulgrew & Volcevski-Kostas, 2012). Khan, Khalid, Khan, and Jabeen (2011) conducted a study on Pakistani male and female students and reported that media exposure had a negative effect on body image.

It is the type of bodily representations, specifically those that result in upward comparison, that negatively influence body image. Men may rate themselves as more fit and toned when shown images of “average, nonmuscular” male physiques (Diedrichs & Lee, 2010; Lorenzen, Grieve, & Thomas, 2004). As noted by Farquhar and Wasylkiw (2007) models and actors typically possess the “ideal” male form, and these are easily available representations. Nonetheless, it is not always the case that exposure to media images will affect how one regards their own body. A small number of studies have reported no significant influence of self-reported body comparison on body dissatisfaction in males (Carlson Jones, 2004; van den Berg et al., 2007). The latter authors suggest this may stem from a tendency among men to engage in comparisons with peers, more so than with the media images of a flawless male form. This indicates a need to re-examine the processes involved in the development of body dissatisfaction among men. Humphreys and Paxton (2004) suggested that media alone is not responsible for the development of a negative body image. The tripartite influence model (Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe, & Tantleff-Dunn, 1999) proposes that peers and parents, in addition to the media, are primarily responsible for the development of body dissatisfaction. Nonetheless, it has been proposed that upward comparison with media images results in body dissatisfaction to a greater extent than upward comparison with friends, peers, and family members (Morrison, Kalin, & Morrison, 2004).

Body image disorders are commonly associated with culture and have long been identified with Western, developed, and industrialized countries (Thompson & Stice, 2001). Indeed, it was previously believed that body image concerns and eating disorders were Western culture-bound syndromes due to the importance placed on physical appearance for success and happiness (Lee, 1996; Thompson et al., 1999). Body image concerns are not the sole domain of a particular culture (Nasser, 1997; Thomas, Khan, & Abdulrahman, 2010), although it had been suggested that the increase in body image concerns that manifest into eating disorders resulted from the process of Westernization (Prince, 1983). However, Pike and Dunne (2015) argued that this does not adequately recognize that other factors besides globalization are at play, and suggested that eating pathologies stem in part from cultural transformation driven by urbanization and industrialization.

Ideal body shapes vary cross-culturally. While individuals from Western cultures typically prefer a thin female body and a muscular male body, many in non-Western countries prefer slightly curvier bodies for women and larger bodies for men (Bush, Williams, Lean, & Anderson, 2001; Cash & Smolak, 2012). Body image disturbances are common among both sexes (Schulte & Thomas, 2013), and interestingly a study conducted in Pakistan, reported that more men than women, displayed dissatisfaction with their bodies (Khan et al., 2011). A small number of studies have attempted to assess body image perceptions of men in Pakistan. Body shape (including height), muscularity, facial features, and hair were identified as body dissatisfaction constructs among university students in Lahore (Tariq & Ijaz, 2015), and 25% of participating males in this study displayed moderate or severe body dissatisfaction. Taqui et al. (2008) reported that in a sample of Pakistani medical students, more males were worried about being overweight than underweight, but that their primary area of concern was scalp hair. More recently, Suhail, Salman, and Salman (2015) identified scalp hair density as the main concern of male students, although this study did not research the issue of body size/shape.

Non-Western countries like Japan, Malaysia, China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore, and Fiji have experienced an increase in rates of body image disorders and eating disorders in recent years (Brokhoff et al., 2012; Chan, Ku, & Owens, 2010; Chisuwa & O’Dea, 2010; Xu et al., 2010). These issues have also been identified in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (Schulte & Thomas, 2013) and Pakistan (Jalees & de Run, 2014). The increase in body image disorders among non-Western countries has been examined under the lens of sociocultural theory, which suggests that cultures which promote the concept of the perfect body (notably, through their media) provide a setting for the development of body dissatisfaction and eating disorders (Furnham & Alibhai, 1983; Tsai, Curbow, & Heinberg, 2003). Due largely to the evolution of mass media, it has been argued that we now live in a “culturally shrunken world” (Swami, 2006, p. 46), wherein media images of perfect bodies are ubiquitous. Irrespective of the culture to which we belong, those who are influenced by the media may experience increased internalization of sociocultural pressures to achieve the unattainable.

When people move to a different country, they may experience discordance between their original culture and the host culture (Soh, Touyz, & Surgenor, 2006; Tsai et al., 2003). The general health of immigrant groups deteriorates with the length of time spent in the host country (Oza-Frank & Cunningham, 2010; Singh & Miller, 2004). In line with the convergence hypothesis (Sam, 2006), the health of immigrants shifts toward a national (host country) norm, which may be poorer than in their country of origin. For immigrants there is interplay between their traditional culture and the culture of the country to which they relocate, and they undergo a process of cultural evolution in which their values, beliefs, and attitudes change and acclimate to the host country (Barry, 2002). Dinicola (1990) argued that anorexia is, in part, a culture change syndrome that develops with cultural and economic evolution brought about by immigration of people to industrialized countries, and Sussman, Truong, and Lim (2007) suggested that eating disorders are evidence of a cultural-transition syndrome. It is therefore plausible to suggest that body image disturbances might also stem from the transition between two different cultures.

The impact of emigration from one’s country of origin on body image may be moderated by other factors. Interestingly, body dissatisfaction was negatively associated with age, and positively associated with self-reported integration in a sample of men who emigrated from Asian countries (Sri Lanka, Pakistan) to Norway (Råberg, Kumar, Holmboe-Ottesen, & Wandel, 2010). The extent to which immigrants adopt beliefs and values of their host culture may affect the risk of body dissatisfaction and eating disorders (Soh et al., 2006). In a systematic review of the literature on cultural change and eating disorders, Doris et al. (2015) identified both greater and lesser acculturation as risk factors for the development of eating disorders. Furthermore, in their review of studies which examined body image perceptions of non-Western immigrant groups in Western countries, Toselli, Rinaldo, and Gualdi-Russo (2016) reported greater body dissatisfaction among those who live in urban areas, who are more likely to have adopted Western beauty ideals. Acculturation, regarded as a desirable end goal for an immigrant population, may, in this instance, be deleterious to psychological well-being.

Body image concerns have been reported among non-Western immigrants to be associated with poor body image and eating disorders. Asian immigrants in Western countries appear more at risk (Sussman et al., 2007). Researchers suggest a need to assess the role played by Asian and Western influences on body image concerns (Jung, Forbes, & Chan, 2010; Watt & Ricciardelli, 2012), as immigrant men may have different body image concerns (e.g., they may be less concerned about muscularity than about their height (Watt & Ricciardelli, 2012). Past studies that have examined body image among men, have focused on those living in Western countries (Ricciardelli, McCabe, Williams, & Thompson, 2007; Yang, Gray, & Pope, 2005). It is important to assess body image concerns of men living in non-Western countries (Ricciardelli et al., 2007), and to identify the risk factors that are associated with body image disturbances in this population (Makino, Tsuboi, & Dennerstein, 2004). Few studies have compared two groups from the same ethnic backgrounds in different countries (Davis & Katzman, 1998) and of these, most have been conducted on women (Abdollahi & Mann, 2001; Furnham & Alibhai, 1983; Gunewardene, Huon, & Zheng, 2001; Sussman et al., 2007; Tsai et al., 2003). Moreover, few have examined media influence and immigration together, making it difficult to draw any conclusions on the potential interaction between these two factors (Warren & Rios, 2013).

This study attempts to address this gap by examining two potential factors associated with body dissatisfaction among non-Western men. The present study compares two groups of young Pakistani men living in two non-Western countries namely the UAE and Pakistan, which hold similar religion, values, traditions, and appearance ideals. However, the UAE is more ethnically diverse than Pakistan. Within the UAE, 86% of the population is composed of non-national residents from countries worldwide (Maceda, 2014), who have diverse cultural practices and asethetic ideals. Based on previous findings, a significant difference in the body image of Pakistani men based on immigration status (i.e., those who had immigrated to the UAE compared with those who lived in Pakistan) was hypothesized. A significant difference in body image between men who were highly influenced by the media when compared with those who were less influenced by the media was expected. Furthermore, it was hypothesized that there would be a significant interaction between immigrant status and media influence on body image, specifically Pakistani men who immigrated to the UAE, and who showed high level of media ideal internalization, would have greater body dissatisfaction than those who remained in Pakistan, and who were less influenced by the media.

Method

Participants

A total of 114 undergraduate Pakistani male students were purposively selected using snowball sampling from a university in Karachi, Pakistan (n = 56) and from an international university in Dubai, UAE (n = 58). The average age of Pakistani-based students was (M = 21.00 years, SD = 1.80) and the average age of the UAE-based students was (M = 21.15 years, SD = 2.30).

Materials

The Body Shape Questionnaire

The English version of the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ-8C; Evans & Dolan, 1993) measured participants’attitudes toward their body. It is a validated shorter version of the original BSQ-34 Questionnaire, which has high internal consistency and test reliability (Cooper, Taylor, Cooper, & Fairburn, 1987; Rosen, Jones, Ramirez, & Waxman, 1996; Warren et al., 2008). Research assessing its psychometric properties in a Brazilian sample reported concurrent and discriminant validity (da Silva, Dias, Moroco, & Campos, 2014). Liu et al. (2015) described the BSQ-8C, administered in their Taiwan-based study, as having good internal reliability. It is an eight item, 6-point Likert-type scale, ranging from never (1) to always (6). Overall scores range from 8 to 48, with higher scores indicating negative body image among the participants. Item 4 was modified with respect to culture of the participants in the current study, from “Have you imagined cutting off fleshy areas of your body?” to “Have you imagined hiding the fleshy areas of your body?” The BSQ-8C had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .88) after the modification of Item 4.

Sociocultural Attitude Towards Appearance Questionnaire

The English version of the Sociocultural Attitude Towards Appearance Questionnaire (SATAQ-3) was used to measure the degree to which people internalize cultural appearance ideals (Thompson, van den Berg, Roehrig, Guarda, & Heinberg, 2004). It is a reliable and validated scale (Thompson et al., 2004), effective in measuring media influence among undergraduate male students (Karazsia & Crowther, 2008). Reliability and validity are also indicated by studies which have examined internalization among women in Jordan (Madanat, Hawks, & Brown, 2006), and a sample that included older immigrant women in the United States (Dunkel, Davidson, & Qurashi, 2010). This 30-item questionnaire has 4 subscales that measure internalization (general and athlete), pressures, and information. Items are rated on 5-point Likert-type scale, and range from (1) definitely disagree to (5) definitely agree. Total scores from the SATAQ-3 were split into two categories using the median group score, 87 (on a scale ranging from 30 to 150), wherein scores above the median were categorized as High Media Influence and scores below the median were categorized as Low Media Influence. Item 6 had been modified to cater to the sex of the participants under study, from “I do not feel pressure from TV or magazines to look pretty.” to “I do not feel pressure from TV or magazines to look good.” In the current study, the SATAQ-3 has a good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .87, after the modification of Item 6.

Procedure

Ethical approval from the university in Dubai was obtained, and written permission from the university in Karachi was obtained prior to data collection. Participants provided informed consent, and all were debriefed following data collection.

Results

The results of descriptive statistics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics Showing Mean Scores for Body Image by Immigrant Status and Media Influence.

| Dependent variable: Body image | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media influence | Immigrant status | M | SD | N |

| Low influence | Pakistan | 18.33 | 8.85 | 30 |

| United Arab Emirates | 20.21 | 7.42 | 33 | |

| Total | 19.32 | 8.12 | 63 | |

| High influence | Pakistan | 24.08 | 9.89 | 26 |

| United Arab Emirates | 31.52 | 8.37 | 25 | |

| Total | 27.73 | 9.83 | 51 | |

| Total | Pakistan | 21.00 | 9.70 | 56 |

| United Arab Emirates | 25.09 | 9.60 | 58 | |

| Total | 23.08 | 9.83 | 114 | |

Note. Higher scores signify body image concerns.

Levene’s test indicated equality of variance for body image dissatisfaction across both groups,Pakistani men in Pakistan and Pakistani men in the UAE, F(3, 110) = 1.035, p > .05. A 2 × 2 factorial analysis of variance identified a significant main effect of immigrant status on body image, F(1, 110) = 8.249, p < .01, ηp2 = .070, with men in the UAE displaying more negative attitudes toward their body (M = 25.08, SD = 9.60), than those living in Pakistan (M = 21.00, SD = 9.69).

Analysis also indicated a highly significant main effect of media influence on body image, F(1, 110) = 27.602, p < .001, ηp2 = .201. Those who scored high (i.e., above the median) on internalization of cultural appearance ideals (M = 27.73, SD = 9.83), displayed greater body image concerns in comparison with those who displayed low levels of internalization (M = 19.32, SD = 8.12).

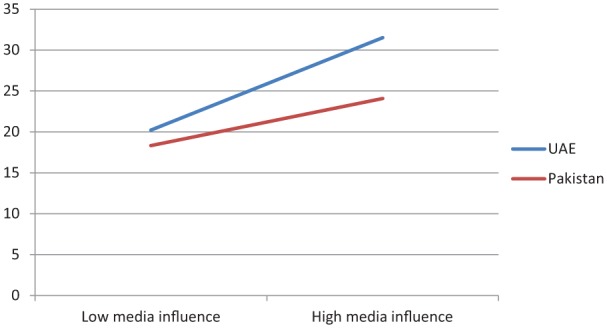

There was a nonsignificant interaction between immigrant status and media influence on body image of Pakistani men, F(1, 110) = 2.939, p = .089, ηp2 = .026 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Means plot showing the influence of immigrant status and media influence on body image.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the effect of media influence and immigration on body image among a small sample of Pakistani men. The first hypothesis, which examined the effect of immigrant status on body image, was supported by the results. In the current study, the difference in body image concerns between men in the UAE and Pakistan may be explained by culture change theory, which states that immigration to industrialized countries increases the likelihood of body dissatisfaction (Dinicola, 1990). Pakistani immigrant men in the UAE undergo cultural evolution, perhaps because they moved to a part of the world which is ethnically diverse, developed, and affluent (Musaiger, bin Zaal, & D’Souza, 2012). In Pakistan, which has a population of 135 million, 97% of the population share the same values, traditions, beliefs (Khan et al., 2011; Malik, 2006), and religion—Islam, which encourages modesty in relation to physical appearance (Jalees & de Run, 2014). The UAE is also an Islamic country with a rich culture of its own (Mady, 2005), but it has gone through a rapid economic and sociocultural change in recent years (Musaiger et al., 2012). Economic growth and industrialization, along with the influx of overseas workers has resulted in a multiethnic society (Mady, 2005), with residents bringing their own languages, religions, and cultures (Fox, Mourtada-Sabbah, & al-Mutawa, 2006). Men in Pakistan live within a culture that places relatively less importance to physical appearance (Jalees & de Run, 2014), among people with shared values, beliefs, and attitudes (Malik, 2006). However, when they immigrate to the UAE, which is a multiethnic society (Mady, 2005) these men are exposed to a variety of cultural backgrounds. They undergo an acculturation process as suggested by Lee (1996), which affects their eating habits, lifestyle, and attitudes toward their bodies. During this process, they may also experience acculturative stress due to cultural clash (Tsai et al., 2003) as they try to adapt to the values and beliefs of the host country and at the same time adhere to their original values, beliefs, and attitudes.

The findings are comparable to past research by Råberg et al. (2010) who reported that Pakistani immigrants in Norway were dissatisfied with their weight. Similarly, they are in keeping with studies which revealed the general body image dissatisfaction of immigrant groups, namely Korean men living in New Zealand, and Chinese men living in Australia (Jung et al., 2010; Watt & Ricciardelli, 2012). Thus, the current study suggests that body image disorders are not culture-bound syndromes. They are culture-change syndromes brought about by cultural and economic evolution. In the current study, immigration brings about a sociocultural and economical change in Pakistani men, which potentially affects their attitudes and habits.

The second hypothesis, which examined the effect of media influence on body image, was also supported by the results. There was a significant effect of internalization on body image, indicating that a high degree of high media influence was, in part, responsible for negative body image. Media influence affected the body image of men in both the UAE and Pakistan samples; however, the former reported somewhat greater body image concerns than the latter. The second hypothesis was based on social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954) and sociocultural theory (Furnham & Alibhai, 1983; Tsai et al., 2003)—that upward comparison and internalization of cultural appearance ideals result in negative self-evaluation. In this study, men who were highly influenced by the media had negative attitudes toward their body. Perhaps this is due to upward comparison and negative self-evaluation caused by internalization of cultural appearance ideals shown by media such as celebrities, athletes, and actors portraying the ultimate male as muscular and lean, which is not always achievable (H. G. Pope et al., 2001). Evidence suggests that body image concerns among both sexes have increased in the UAE and Pakistan due to a general increase in media exposure (Jalees & de Run, 2014; Mady, 2005). One in five men compare themselves with actors, athletes, and models; moreover, nearly half of those seeking cosmetic surgery in the UAE are men (Kemp, 2012).

These findings are consistent with past research, which suggest that men develop body image dissatisfaction when they are exposed to media showing ideal figures (Bardone-Cone et al., 2008; Blond, 2008; Jalees & de Run, 2014; Khan et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2010). This is supported by research that suggests that it is the type of bodily representation that is important—showing men “normal,” “non-muscular” representations of the male form results in increased body satisfaction (Diedrichs & Lee, 2010). Ferguson (2013) claimed there is little evidence for the effects of media influence on body dissatisfaction of males, although he did suggest that some studies which fail to demonstrate an effect may have methodological errors. Grabe, Ward, and Hyde (2008) noted the methodological rigor of experimental studies that have identified effects in studies among a wide range of samples with differing measures, and cited supportive evidence from correlational studies. Nonetheless, the authors recognize that effects of media influence on body image are not uniform, and that this relationship can be affected by preexisting body dissatisfaction, media literacy (in particular, critical thinking), social comparison, and many other factors (López-Guimerà, Levine, Sánchez-Carracedo, & Fauquet, 2010; McLean, Paxton, & Wertheim, 2016).

The third hypothesis examined the interaction effect of media influence and immigrant status on body image. Results have demonstrated a non-significant interaction effect of media influence and immigrant status on body image. This indicates that both media influence and immigrant status independently play a role in the development of negative body image among Pakistani men.

Van den Berg et al. (2007) suggested that processes involved in the development of negative body image among men should be reexamined. This study has tried to fill that gap, and results suggest that male immigrants are at a higher risk of developing negative attitudes toward their body than those who remain in their country of origin. Men may also develop a negative body image due to susceptibility to media influence. The findings from this study will add to the existing literature on body image among non-Western men, and may further assist clinicians in designing interventions aimed at reducing the negative effects of exposure to unrealistic media ideals, and with stressors associated with immigration, on body image among this population. Interventions can be designed by increasing awareness of potentially harmful effects of media and culturally-constructed ideals because evidence suggests that providing school-based media literacy can reduce the negative effects of such images being shown on the media (Wilksch, Tiggemann, & Wade, 2006). Furthermore, the media may have a positive influence in promoting benefits of optimal nutrition and exercise toward the goal of achieving a healthy body.

A potential limitation of this study relates to the educational status of the participants; these young men belong to a more educated cohort than the national average; only 34.6% of males in Pakistan were able to attend secondary school between 2008 and 2012 (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2013). Thus, this sample may not be a true representative of all Pakistani men and the findings may only generalize to educated, adult Pakistani men who research suggests are at a greater risk of developing negative body image (Khan et al., 2011). The questionnaire used to assess body image (BSQ-8C; Evans & Dolan, 1993) focuses on concerns about fat, and thus may not capture the nuances of body image that might manifest in this sample. Indeed, Pook, Tuschen-Caffier, and Brähler (2008) argued that this measure may not be suitable for assessing body dissatisfaction among males. Although males may certainly display concerns about excess fat and overweight, past research suggests this is more typical of an older sample (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2003, 2004; McCreary & Sasse, 2000), with younger men reporting dissatisfaction with lack of muscle definition (Murray & Lewis, 2014) or with size (i.e., they may wish to gain or lose weight; McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2004). Respondents in this study may have had body image concerns which the current study did not address.

Apart from immigration status, there are other underlying factors such as level of acculturation, acculturative stress, culture of host country, and home country that likely affect body image among immigrants, and these should be examined in future studies. Moreover, sociocultural factors, such as pressure from peers, friends, and family members (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2001) could be assessed to determine whether these factors interact with media messages to have effects on body image (Thompson & Stice, 2001). An avenue for further research into internalization of the body image ideal, is the extent to which body image norms are internalized due to the use of social media (Meier & Gray, 2014; Perloff, 2014). Moreover, future studies might include a qualitative component to gain insight into the lived experiences of Pakistani men in relation to their body image. As results indicate that the level of media influence played a role in negative body image, irrespective of immigration status, it is important to not only examine media content but also increase awareness of the influence of the media and culturally constructed versions of physical attractiveness (Wilksch et al., 2006).

In conclusion, the present study is one of very few investigating the effects of the media influence and immigrant status on body image among non-Western men. Although the hypotheses were largely supported, this research highlights the need for further investigation of the potentially multiple factors implicated in causing body image dissatisfaction among this underresearched population. In doing so, we may begin to understand the negative impact on physical and mental well-being, and develop preventative or therapeutic interventions.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abdollahi P., Mann T. (2001). Eating disorder symptoms and body image concerns in Iran: Comparisons between Iranian women in Iran and in America. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 30, 259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams G., Turner H., Bucks R. (2005). The experience of body dissatisfaction in men. Body Image, 2, 271-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbour K. P., Martin Ginis K. A. (2006). Effects of exposure to muscular and hypermuscular media images on young men’s muscularity dissatisfaction and body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 3, 153-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baghurst T., Hollander D. B., Nardella B., Haff G. G. (2006). Change in sociocultural ideal male physique: An examination of past and present action figures. Body Image, 3, 87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird A. L., Grieve F. G. (2006). Exposure to male models in advertisements leads to a decrease in men’s body satisfaction. North American Journal of Psychology, 8, 115-121. [Google Scholar]

- Bardone-Cone A. M., Cass K. M., Ford J. A. (2008). Examining body dissatisfaction in young men within a biopsychosocial framework. Body Image, 5, 183-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlett C. P., Vowels C. L., Saucier D. A. (2008). Meta-analyses of the effects of media images on men’s body-image concerns. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27, 279-310. [Google Scholar]

- Barry D. T. (2002). An ethnic identity scale for East Asian immigrants. Journal of Immigrant Health, 4, 87-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill A. J., Wilhelm S. (2014). Body image distortions, weight, and depression in adolescent boys: Longitudinal trajectories into adulthood. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15, 445-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blond A. (2008). Impacts of exposure to images of ideal bodies on male body dissatisfaction: A review. Body Image, 5, 244-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brokhoff M., Mussap A. J., Mellor D., Skouteris H., Ricciardelli L. A., McCabe M. P., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M. (2012). Cultural influences on body dissatisfaction, body change behaviours, and disordered eating of Japanese adolescents. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 15, 238-248. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns G. L., Carter M. M. (2015). Ethnic differences in the effects of media on body image: The effects of priming with ethnically different or similar models. Eating Behaviors, 17, 33-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunson J. A., Øverup C. S., Nguyen M. L., Novak S. A., Smith C. V. (2014). Good intentions gone awry? Effects of weight-related social control on health and well-being. Body Image, 11, 1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush H. M., Williams R. G., Lean M. E., Anderson A. S. (2001). Body image and weight consciousness among South Asian, Italian and general population women in Britain. Appetite, 37, 207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill S., Mussap A. J. (2007). Emotional reactions following exposure to idealized bodies predict unhealthy body change attitudes and behaviors in women and men. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 62, 631-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Jones D. (2004). Body image among adolescent girls and boys: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 40, 823-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash T. F. (2004). Body image: Past, present, and future. Body Image, 1, 1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash T. F., Henry P. E. (1995). Women’s body image: The results of a national survey in the U.S.A. Sex Roles, 33, 19-28. [Google Scholar]

- Cash T. F., Smolak L. (2012). Body image: A handbook of science, practice, and prevention (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chan C. K. Y., Ku Y., Owens R. G. (2010). Perfectionism and eating disturbances in Korean immigrants: Moderating effects of acculturation and ethnic identity. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 13, 293-302. [Google Scholar]

- Chisuwa N., O’Dea J. A. (2010). Body image and eating disorders amongst Japanese adolescents. A review of the literature. Appetite, 54, 5-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper P. J., Taylor M. J., Cooper Z., Fairburn C. G. (1987). The development and validation of the Body Shape Questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6, 485-494. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins L. H., Lehman J. (2007). Eating disorders and body image concerns in Asian American women: Assessment and treatment from a multicultural and feminist perspective. Eating Disorders, 15, 217-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva W. R., Dias J. C. R., Moroco J., Campos J. A. D. B. (2014). Confirmatory factor analysis of different versions of the Body Shape Questionnaire applied to Brazilian university students. Body Image, 11, 384-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakanalis A., Zanetti A. M., Riva G., Colmegna F., Volpato C., Madeddu F., Clerici M. (2015). Male body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptomatology: Moderating variables among men. Journal of Health Psychology, 20, 80-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C., Katzman M. A. (1998). Chinese men and women in the United States and Hong Kong: Body and self-esteem ratings as a prelude to dieting and exercise. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 23, 99-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derenne J. L., Beresin E. V. (2006). Body image, media, and eating disorders. Academic Psychiatry, 30, 257-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diedrichs P. C., Lee C. (2010). GI Joe or Average Joe? The impact of average-size and muscular male fashion models on men’s and women’s body image and advertisement effectiveness. Body Image, 7, 218-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinicola V. F. (1990). Anorexia multiforme: Self-starvation in historical and cultural context: Part II. Anorexia nervosa as a culture-reactive syndrome. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review, 27, 245-286. [Google Scholar]

- Doris E., Shekriladze I., Javakhishvili N., Jones R., Treasure J., Tchanturia K. (2015). Is cultural change associated with eating disorders? A systematic review of the literature. Eating and Weight Disorders: Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 20, 149-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A., Yee D. K. (1987). Men and body image: Are males satisfied with their body weight? Psychosomatic Medicine, 49, 626-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel T. M., Davidson D., Qurashi S. (2010). Body satisfaction and pressure to be thin in younger and older Muslim and non-Muslim women: The role of Western and non-Western dress preferences. Body Image, 7, 56-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C., Dolan B. (1993). Body Shape Questionnaire: Derivation of shortened “alternate forms.” International Journal of Eating Disorders, 13, 315-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar J. C., Wasylkiw L. (2007). Media images of men: Trends and consequences of body conceptualization. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 8, 145-160. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson C. J. (2013). In the eye of the beholder: Thin-ideal media affects some, but not most, viewers in a meta-analytic review of body dissatisfaction in women and men. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2, 20-37. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. (1954). A theory of social comparison process. Human Relations, 7, 117-140. [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. W., Mourtada-Sabbah N., al-Mutawa M. (2006). Globalization and the Gulf. Oxon, England: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick D. A., Fessler D. M. T., Haselton M. G. (2005). Do representations of male muscularity differ in men’s and women’s magazines? Body Image, 2, 81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnham A., Alibhai N. (1983). Cross-cultural differences in the perception of female body shapes. Psychological Medicine, 13, 829-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner D. M. (1997). The 1997 body image survey results. Psychology Today, 30, 30-44. [Google Scholar]

- Grabe S., Ward L. M., Hyde J. S. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 460-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieve F. G. (2007). A conceptual model of factors contributing to the development of muscle dysmorphia. Eating Disorders, 15, 63-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunewardene A., Huon G. F., Zheng R. (2001). Exposure to westernization and dieting: A cross-cultural study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29, 289-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves D. A., Tiggemann M. (2009). Muscular ideal media images and men’s body image: Social comparison processing and individual vulnerability. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 10, 109-119. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94, 319-340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins E. T. (1989). Self-discrepancy theory: What patterns of self-beliefs cause people to suffer? Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 22, 93-136. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys P., Paxton S. J. (2004). Impact of exposure to idealised male images on adolescent boys’ body image. Body Image, 1, 253-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalees T., de Run E. C. (2014). Body image of Pakistani consumers. Journal of Management Science, 1(1), 16-34. [Google Scholar]

- Jung J., Forbes G. B., Chan P. (2010). Global body and muscle satisfaction among college men in the United States and Hong Kong-China. Sex Roles, 63, 104-117. [Google Scholar]

- Karazsia B. T., Crowther J. H. (2008). Psychological and behavioral correlates of the SATAQ-3 with males. Body Image, 5, 109-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp R. (2012, January 30). Are men in the UAE suffering dangerously in pursuit of the perfect body? The National. Retrieved from http://www.thenational.ae/lifestyle/well-being/are-men-in-the-uae-suffering-dangerously-in-pursuit-of-the-perfect-body

- Kennedy M. A., Templeton L., Gandhi A., Gorzalka B. B. (2004). Asian body image satisfaction: Ethnic and gender differences across Chinese, Indo-Asian, and European-descent students. Eating Disorders, 12, 321-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A. N., Khalid S., Khan H. I., Jabeen M. (2011). Impact of today’s media on university student’s body image in Pakistan: A conservative, developing country’s perspective. BMC Public Health, 11, 379. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law C., Labre M. P. (2002). Cultural standards of attractiveness: A thirty-year look at changes in male images in magazines. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 79, 697-711. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. (1996). Reconsidering the status of anorexia nervosa as a western culture-bound syndrome. Social Science & Medicine, 42, 21-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowich M., Oliffe J. L., Clarke L. H., Hannan-Leith M. (2017). Male body practices. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11, 452–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leit R. A., Pope H. G., Gray J. J. (2001). Cultural expectations of muscularity in men: The evolution of Playgirl centerfolds. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29, 90-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. Y., Tseng M. C. M., Chen K. Y., Chang C. H., Liao S. C., Chen H. C. (2015). Sex difference in using the SCOFF questionnaire to identify eating disorder patients at a psychiatric outpatient clinic. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 57, 160-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Guimerà G., Levine M. P., Sánchez-Carracedo D., Fauquet J. (2010). Influence of mass media on body image and eating disordered attitudes and behaviors in females: A review of effects and processes. Media Psychology, 13, 387-416. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen L. A., Grieve F. G., Thomas A. (2004). Brief report: Exposure to muscular male models decreases men’s body satisfaction. Sex Roles, 51, 743-748. [Google Scholar]

- Maceda C. (2014, August 25). Dubai one of world’s most influential cities: Forbes. Gulf News. Retrieved from http://gulfnews.com/business/sectors/general/dubai-one-of-world-s-most-influential-cities-forbes- 11373781 [Google Scholar]

- Madanat H. N., Hawks S. R., Brown R. B. (2006). Validation of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 among a random sample of Jordanian women. Body Image, 3, 421-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mady A. M. (2005). Roles and effects of media in the Middle East and the United States. Leavenworth, KS: School of Advance Military Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Maida D. M., Armstrong S. L. (2005). The classification of muscle dysmorphia. International Journal of Men’s Health, 4, 73-91. [Google Scholar]

- Makino M., Tsuboi K., Dennerstein L. (2004). Prevalence of eating disorders: A comparison of Western and non-Western countries. Medscape General Medicine, 6, 49 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1435625/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik I. H. (2006). Culture and customs of Pakistan. London, England: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe M. P., Ricciardelli L. A. (2001). Parent, peer, and media influences on body image and strategies to both increase and decrease body size among adolescent boys and girls. Adolescence, 36, 225-240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe M. P., Ricciardelli L. A. (2003). Body image and strategies to lose weight and increase muscle among boys and girls. Health Psychology, 22, 39-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe M. P., Ricciardelli L. A. (2004). Body image dissatisfaction among males across the lifespan: A review of past literature. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56, 675-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary D. R., Hildebrandt T. B., Heinberg L. J., Boroughs M., Thompson J. K. (2007). A review of body image influences on men’s fitness goals and supplement use. American Journal of Men’s Health, 1, 307-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary D. R., Sasse D. K. (2000). Exploring the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. Journal of American College Health, 48, 297-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary D. R., Saucier D. M. (2009). Drive for muscularity, body comparison, and social physique anxiety in men and women. Body Image, 6, 24-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean S. A., Paxton S. J., Wertheim E. H. (2016). Does media literacy mitigate risk for reduced body satisfaction following exposure to thin-ideal media? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1678-1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier E. P., Gray J. (2014). Facebook photo activity associated with body image disturbance in adolescent girls. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17, 199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison T. G., Kalin R., Morrison M. A. (2004). Body-image evaluation and body-image investment among adolescents: A test of sociocultural and social comparison theories. Adolescence, 39, 571-592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morry M. M., Staska S. L. (2001). Magazine exposure: Internalization, self-objectification, eating attitudes, and body satisfaction in male and female university students. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 33, 269-279. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgrew K. E., Volcevski-Kostas D. (2012). Short term exposure to attractive and muscular singers in music video clips negatively affects men’s body image and mood. Body Image, 9, 543-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray T., Lewis V. (2014). Gender-role conflict and men’s body satisfaction: The moderating role of age. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15, 40-48. [Google Scholar]

- Musaiger A. O., bin Zaal A. A., D’Souza R. (2012). Body weight perception among adolescents in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 27, 1966-1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasser M. (1997). Culture and weight consciousness. London, England: Routledge. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivardia R., Pope H. G., Borowiecki J. J., Cohane G. H. (2004). Biceps and body image: The relationship between muscularity and self-esteem, depression, and eating disorder symptoms. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 5, 112-120. [Google Scholar]

- Oza-Frank R., Cunningham S. A. (2010). The weight of US residence among immigrants: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews, 11, 271-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perloff R. M. (2014). Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles, 71, 363-377. [Google Scholar]

- Pike K. M., Dunne P. E. (2015). The rise of eating disorders in Asia: A review. Journal of Eating Disorders, 3, 33 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4574181/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pook M., Tuschen-Caffier B., Brähler E. (2008). Evaluation and comparison of different versions of the Body Shape Questionnaire. Psychiatry Research, 158, 67-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C. G., Pope H. G., Menard W., Fay C., Olivardia R., Phillips K. A. (2005). Clinical features of muscle dysmorphia among males with body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image, 2, 395-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope H. G., Olivardia R., Borowiecki J. J., Cohane G. H. (2001). The growing commercial value of the male body: A longitudinal survey of advertising in women’s magazines. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 70, 189-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope H. G., Olivardia R., Gruber A., Borowiecki J. (1999). Evolving ideals of male body image as seen through action toys. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 26, 65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope H. G., Phillips K. A., Olivardia R. (2000). The Adonis complex: The secret crisis of male body obsession. New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Primus M. (2014). Body dissatisfaction and males: A conceptual model. Scholarly Horizons: University of Minnesota, Morris Undergraduate Journal, 1(1), 1-24. [Google Scholar]

- Prince R. (1983). Is anorexia nervosa a culture-bound syndrome? Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review, 20, 299-302. [Google Scholar]

- Råberg M., Kumar B., Holmboe-Ottesen G., Wandel M. (2010). Overweight and weight dissatisfaction related to socio-economic position, integration and dietary indicators among South Asian immigrants in Oslo. Public Health Nutrition, 13, 695-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardelli L. A., McCabe M. P., Williams R. J., Thompson J. K. (2007). The role of ethnicity and culture in body image and disordered eating among males. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 582-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J. C., Jones A., Ramirez E., Waxman S. (1996). Body Shape Questionnaire: Studies of validity and reliability. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 20, 315-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sam D. L. (2006). Acculturation and health. In Sam D. L., Berry J. W. (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (pp. 452-468). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte S. J., Thomas J. (2013). Relationship between eating pathology, body dissatisfaction and depressive symptoms among male and female adolescents in the United Arab Emirates. Eating Behaviors, 14, 157-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G. K., Miller B. A. (2004). Health, life expectancy, and mortality patterns among immigrant populations in the United States. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 95, I14- I21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soh N. L., Touyz S. W., Surgenor L. J. (2006). Eating and body image disturbances across cultures: A review. European Eating Disorders Review, 14, 54-65. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton P., McIntyre T., Bannatyne A. (2016). Body image avoidance, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology: Is there a difference between male gym users and non-gym users? American Journal of Men’s Health, 10, 100-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 825-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhail M., Salman S., Salman F. (2015). Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in medical versus nonmedical students: A questionnaire based pilot study. Journal of Pakistan Association of Dermatologists, 25, 162-168. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman N. M., Truong N., Lim J. (2007). Who experiences “America the beautiful”? Ethnicity moderating the effect of acculturation on body image and risks for eating disorders among immigrant women. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 3, 29-49. [Google Scholar]

- Swami V. (2006). The influence of body weight and shape in determining female and male physical attractiveness. In Kindes M. V. (Ed.), Body image: New research (pp. 35-61). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science. [Google Scholar]

- Taqui A. M., Shaikh M., Gowani S. A., Shahid F., Khan A., Tayyeb S. M., . . . Naqvi H. A. (2008). Body dysmorphic disorder: Gender differences and prevalence in a Pakistani medical student population. BMC Psychiatry, 8(1), 20. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq M., Ijaz T. (2015). Development of Body Dissatisfaction Scale for university students. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 30, 305-322. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J., Khan S., Abdulrahman A. A. (2010). Eating attitudes and body image concerns among female university students in the United Arab Emirates. Appetite, 54, 595-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. K., Heinberg L. J., Altabe M., Tantleff-Dunn S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. K., Stice E. (2001). Thin-ideal internalization: Mounting evidence for a new risk factor for body-image disturbance and eating pathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 181-183. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. K., van den Berg P., Roehrig M., Guarda A. S., Heinberg L. J. (2004). The Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Scale-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and validation. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35, 293-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toselli S., Rinaldo N., Gualdi-Russo E. (2016). Body image perception of African immigrants in Europe. Globalization and Health, 12(1), 48. doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0184-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai G., Curbow B., Heinberg L. (2003). Sociocultural and developmental influences on body dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors of Asian women. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191, 309-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiantas G., King R. M. (2001). Similarities in body image in sisters: The role of sociocultural internalization and social comparison. Eating Disorders, 9, 141-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. (2013). Pakistan: Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/pakistan_pakistan_statistics.html

- van den Berg P., Paxton S. J., Keery H., Wall M., Guo J., Neumark-Sztainer D. (2007). Body dissatisfaction and body comparison with media images in males and females. Body Image, 4, 257-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren C. S., Cepeda-Benito A., Gleaves D. H., Moreno S., Rodriquez S., Fernandez M. C., . . . Pearson C. A. (2008). English and Spanish versions of the Body Shape Questionnaire: Measurement equivalence across ethnicity and clinical status. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41, 265-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren C. S., Rios R. M. (2013). The relationships among acculturation, acculturative stress, endorsement of Western media, social comparison, and body image in Hispanic male college students. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14, 192-201. [Google Scholar]

- Watt M., Ricciardelli L. A. (2012). A qualitative study of body image and appearance among men of Chinese ancestry in Australia. Body Image, 9, 118-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilksch S. M., Tiggemann M., Wade T. D. (2006). Impact of interactive school-based media literacy lessons for reducing internalization of media ideals in young adolescent girls and boys. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39, 385-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willet E. (2007). Negative body image. New York, NY: Rosen. [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Mellor D., Kiehne M., Ricciardelli L. A., McCabe M. P., Xu Y. (2010). Body dissatisfaction, engagement in body change behaviors and sociocultural influences on body image among Chinese adolescents. Body Image, 7, 156-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. J., Gray P., Pope H. G. (2005). Male body image in Taiwan versus the West: Yanggang Zhiqi meets the Adonis complex. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 263-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]