Abstract

The purpose of the study was to explore, within cultural and societal contexts, the factors of spousal HIV transmission as described by the experiences of HIV-positive Cambodian men. Using qualitative research methods, the researchers collected data from in-depth interviews with 15 HIV-positive Cambodian men of seroconcordant couples recruited from an HIV/AIDS clinic in Phnom Penh. Using a model of HIV transmission from husbands to wives, the questions were designed to elicit the men’s perspectives on the topics of promiscuity, masculinity, condom use in marriage, the image of the ideal Cambodian woman, and attitudes toward sex and marriage. Directed content analysis was used to analyze the interview data. The main results were as follows: (a) men involved with sex workers perceived this as a natural behavior and a necessary part of being an approved member in a male peer group, (b) married men never used condoms during sex with their wives prior to their HIV diagnosis, (c) men perceived a good wife as one who is diligent and loyal to her husband, and (4) men’s attitudes toward sex and marriage (e.g., sex perceived as a part of life pleasure) differed from those of their wives. Promoting honest spousal communication about sexuality, maintaining men’s marital fidelity, and increasing women’s comfort in the use of sexual techniques are suggested as strategies for reducing HIV transmission within marriage in Cambodia. Future interventions should focus on reshaping men’s behaviors and changing cultural norms to protect them and their spouses from HIV infection.

Keywords: Cambodia, HIV, marriage, men, transmission

Introduction

At the end of 2013, an estimated 4.8 million people in Asia and the Pacific were living with HIV, the largest number outside of sub-Saharan Africa (United Nations & AIDS, 2014). Most HIV-infected women in the region had acquired the disease from their husbands practicing risky sex behaviors outside of marriage (United Nations & AIDS, 2014). Marriage has been reported as a risk factor for HIV infection among women in other areas as well, with married women reporting an exposure rate to HIV infection that is three times higher than that of their unmarried counterparts (De Coninck, Feyissa, Ekström, & Marrone, 2014). Of the Southeast Asian countries, Cambodia has been hardest hit by the HIV epidemic (National Center for HIV/AIDS Dermatology and STD, 2011), with spousal HIV transmission being the most common origin of new HIV cases, cited as the source for 48% of new infections in 2014 (National AIDS Authority, 2015). As early as 2009, two thirds of Cambodian women diagnosed with HIV self-reported being infected by their husbands (Roberts, 2009). The first Cambodia national population survey suggested interventions be developed that focused on reducing HIV transmission among spouses by empowering women through education and better access to information (Sopheab, Saphonn, Chhea, & Fylkesnes, 2009).

In any country, the transmission of HIV within a marriage needs to be understood through the social and cultural contexts affecting men’s risky sexual behaviors and women’s vulnerability to HIV infection (Logan, Cole, & Leukefeld, 2002; Yang, Lewis, & Kraushaar, 2013). A gender relations approach to health informs how social environments shape men’s and women’s health (Schofield, Connell, Walker, Wood, & Butland, 2000). In Cambodia, the patriarchal culture holds that wives must always remain subordinate to their husbands; the Code of Women states that a wife is the physical property of her husband (Nakagawa, 2006). Cambodian women have reported that they do not enjoy freedom in their social activities, such as being able to attend parties or meet their female friends (Eng, Li, Mulsow, & Fischer, 2010). The ideal Cambodian woman is obedient and virtuous, following her husband’s lead in sexual relations to avoid marital arguments and avoiding marital arguments preserve household harmony (Nakagawa, 2006; Yang, 2012).

Being involved with sex workers is considered a right and need for a Cambodian man, accepted by his wife and society, and is illustrated by a popular local proverb, “No one eats sour soup every day” (Hong & Chhea, 2009; Yang, 2012). Cambodian men tend to visit sex workers as a sign of masculinity and are encouraged to have multiple sexual partners as part of presenting as a strong man (Family Health International, 2002). Extramarital sex often occurs when men are required to travel away from home for lengthy amounts of time due to work or when wives are not able to have sex (Sopheab, Fylkesnes, Vun, & O’Farrell, 2006). Men not using condoms has been tied to both excessive alcohol consumption and a dislike of condom use during sex (Family Health International, 2002; Phan & Patterson, 1994). Consistent condom use by married men during sex with brothel- and nonbrothel-based HIV-positive sex workers is lower than that of single men (Sok et al., 2008). The conversation over condom use is difficult for Cambodian wives; the husbands interpret it as a sign of their wives’ distrust (Marston & King, 2006; Webber et al., 2010). In 2008, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs reported that only 1% of Cambodian men used condoms during sexual intercourse within their marriage (Ministry of Women’s Affairs, 2008). In addition to the male-oriented attitude of Cambodian society, Cambodian wives also find their ability to discuss safe sex behaviors with their husbands limited by their lack of education and information about condom use (Menon, 2003; Yang, 2012). One study argues that an important factor of HIV transmission within marriage is the different attitudes held by women and men toward sex outside of marriage (Yang, Lewis, & Wonjar, 2016). In that study, the female participants explained that wives often considered sex as work, while husbands enjoyed sex as part of their personal pleasure, and wives usually entered marriage as virgins, while husbands experienced premarital sex.

Since women’s vulnerability to HIV is a result of specific behaviors of their husbands, such as pursuing extramarital sexual relations and using condoms consistently (Mane & Aggleton, 2001; Phinney, 2008), it is critical to involve male partners in prevention programs. Thus, understanding the culturally based mechanisms in men’s lives that influence HIV transmission from husbands to wives is an urgent first step toward the development of effective prevention approaches. Very little research has been conducted to examine the thoughts, perspectives, and experiences of men and women who have experienced the spousal transmission of HIV in the Cambodian context. A previous research study conducted a systematic review of the available literature to develop a model of HIV transmission between husbands and wives in Cambodia (Yang et al., 2013). However, until August 2015, no studies examined the sociocultural influences on the transmission of HIV in marriage from the Cambodian male point of view. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the factors and culturally embedded environment that affect the transmission of HIV from Cambodian husbands to wives from the perspectives of men in HIV seroconcordant relationships. The main topics explored were the environment of promiscuity, perceptions of masculinity, condom use in marriage, the image of the ideal Cambodian woman, and attitudes to sex and marriage. The findings of this study will guide effective and culturally acceptable couple-based HIV prevention programs.

Method

Study Setting

The Sihanouk Hospital Center of HOPE (SHCH) provides HIV/AIDS care and other medical services. It is located in Phnom Penh, the capital city of Cambodia, and served as the setting for recruitment and data collection. Currently, about 3,700 HIV-infected adults from all Cambodian provinces are enrolled in the program, and about 70 to 100 adults needing HIV/AIDS medication and care come to the center every day for regular consultation.

Study Design

This study employed a qualitative design utilizing individual, semistructured, in-depth interviews. The modified model of HIV transmission from husbands to wives (Yang et al., 2016) was used as a conceptual framework for the study design and analysis, which was developed with data from women infected with HIV by their spouses (hereinafter referred to as Yang’s model).Yang’s model consists of four categories. Based on the four categories, this study’s interview questions were designed to elicit the men’s perspectives on the following topics: (a) perceptions of men’s involvement with sex workers, (b) meanings of masculinity, (c) perspectives of condom use within marriage, (d) the image of a good wife, (e) the meaning of sex, (f) perspectives on the use of sexual techniques, and (g) the purpose of marriage (Table 1). This study utilized Yang’s model to compare and confirm the perspectives and experiences between women (Yang’s model) and men (this study) so that the model of spousal HIV transmission can be updated. Additional questions were asked whenever more detailed information, clarification, or understanding of participants’ stories were needed. Examples of probing questions include (a) “Tell me more about that . . . ,” (b) “Tell me what you meant by . . . ,” and (c) “What are experiences of what you just said?” Before starting an interview, demographic information about general lifestyle (spousal characteristics, household information) and HIV status (years since diagnosis, CD4 cell count) was gathered.

Table 1.

Interview Questions and Main Results.

| Category in Yang’s model | Topic | Interview question | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Husband’s involvement with commercial sex workers | 1. Perceptions of men’s involvement with sex workers | ● I understand that it is common in Cambodia for a man to have sex with another woman when he cannot have sex with his wife. What do you know about this? ● Can you share your experience regarding this? |

● Involvement with sex workers: Natural behavior of men |

| 2. Meanings of masculinity | ● What is the meaning of “being a man” to you? | ● Masculinity: Membership in a male peer group | |

| Unprotected sex between an HIV-positive husband and his uninfected wife | 3. Perspectives of condom use by a married couple | ● What are your beliefs about the use of male condoms by a married couple? | ● No condom usage in marriage prior to diagnosis |

| Cultural values of the ideal Khmer woman | 4. The image of a good wife | ● What qualities are particularly important for a good wife to you? | ● Image of a good wife: Diligent and loyal |

| Different attitudes of woman and men toward sex and marriage | 5. The meaning of sex | ● Could you tell me what the meaning of sex is for you? | ● Meaning of sex: A part of life pleasure |

| 6. Perspectives on the use of sexual techniques | ● What are your beliefs about using different sexual techniques to increase the happiness and satisfaction from sex? | ● Perspectives on using sexual techniques: Useful but only with a sex worker | |

| 7. Purpose of marriage | ● What are things that you expected from marriage when you were first married? | ● Purpose of marriage: Children and stability |

Data Collection Method

Fifteen Cambodian men were purposively selected who were (a) married, (b) diagnosed as HIV-positive, (c) married to a woman diagnosed as HIV-positive (based on self-report), and (d) able to sign the written informed consent form. The study purpose, process, and methods were officially introduced in an infectious department meeting of doctors, nurses, counsellors, and support group leaders. With the support of the department, a site intermediary worked to recruit participants while patients waited to see the health care providers. The site intermediary presented the study purpose, eligibility criteria, and participation protocols on an individual basis to men in the SHCH waiting area. When a person showed interest in the study, their eligibility was screened. Potential participants were given information about the study; when a person agreed to participate after being apprised of the study, a time was set for the interview. All participants were asked to sign a written informed consent form prior to starting the interview process and were told they could terminate the interview at any time. The hospital provided a soundproofed office in which the confidential interviews took place; male participants were interviewed one-on-one, separately from their wives. Each interview lasted between 35 and 67 minutes, with an average of 60 minutes per interview, and was recorded on a digital voice recorder. Recruitment and interviews were conducted in July and August of 2015, and recruitment continued until the data arrived at saturation. Ethics approval was obtained from the Chonbuk National University Institutional Human Subjects Review Committee and the National Ethics Committee for Health Research of the Cambodia Ministry of Health before the study began. Participants were given the local cash equivalent of US$5 in appreciation of their time.

Data Management and Analysis

All recordings were transcribed in Khmer, the local language, then translated into English and verified for accuracy by a professional translator. The senior author and the translator reviewed both versions to ensure the conceptual and semantic equivalence of meaning between the original and translated data. The translator double-checked the transcripts by listening to audio files of the interviews.

Directed content analysis was used to analyze the interview data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). The directed approach to content analysis helps determine the initial coding scheme based on an existing theory or theoretical framework. To identify key themes and obtain a sense of the data as a whole, the first author read through the transcripts several times and with great care. Using Yang’s model (Yang et al., 2016), which presented the categories of HIV transmission from husbands to wives from the women’s perspectives, key predetermined concepts were identified as initial coding categories (see Table 1). Next, based on this initial analysis, key messages and quotations were identified. The coauthors discussed the structure of the findings and appropriateness of the outstanding quotations. The text data were managed using ATLAS.ti 6.0, a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software program. To maintain study trustworthiness, analysis was consistently monitored throughout the period of data collection and analysis via the use of the senior author’s reflective daily diaries and the careful scrutiny of interview interpretations, recorded transcriptions, and script translations. The senior author debriefed each interview with the interpreter using the reflective daily diaries.

Results

Characteristics of Study Participants

The 15 participants in this study visited the SHCH for ongoing medical care. They were an average of 44 years old (range 29-63), had been married for 17 years on average (range 5-36), and had been HIV-positive for an average of 7 years (range 0.5-17). Their wives were an average of 37 years old (range 27-56) and had been HIV-positive for an average of 6 years (range 0.5-12). Fourteen of the men originally came from rural areas, and nine lived in Phnom Penh at the time of the study. The mean level of education for the participants was 9 years more than that of their wives (5 years). Participants had been in antiretroviral therapy for an average of 6 years (range 0.5-11), and the average of their CD4 cell count was 392 (range 44-800). All of the men reported being employed (e.g., construction labor, farmer, seller), with household incomes ranging from US$75 to US$500 per month and averaging US$228. During the interview, most of the participants’ mode of HIV infection was self-identified as sexual relations with sex workers.

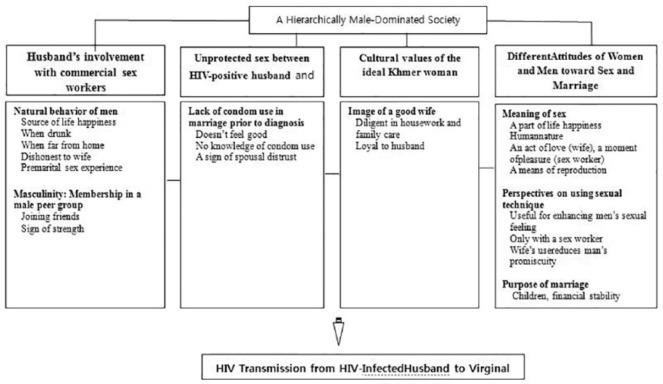

Data analysis revealed themes from participants’ perspectives and experiences. The interview questions lead to these those themes on each topic. Figure 1 outlines factors of each category explored in this study.

Figure 1.

Model of HIV Transmission Between Husbands and Wives: Male Perspectives.

Involvement With Sex Workers: Natural Behavior of Men

The participants perceived a man’s sexual behavior outside of marriage as part of man’s nature and important to man’s life happiness. Most men reported joining a party and drinking with friends, then naturally desiring to have sex when drunk. The men reported enjoying alcohol and believing that drinking provides happiness and release from stress, but ultimately makes them forget everything and leads to visiting sex workers.

Most of men when they have party and drink outside always automatically think about sex, and that’s happen in most men. When they come back and attempt to have sex with wife but wife rejects. Then, they will go out for sex. That’s [what] most of man do. (Linn, age 36)

In particular, the men reported seeking out sex shops when traveling away from home for an extended amount of time to work. The participants viewed this practice as common and normal, a natural part of men’s behavior in Cambodia, not as something bad or strange.

All men when they stay away from wife they wish to get another girl for sex because when we go out it take long time it hard to meet wife and then if they feel sex they just go out to find the sex service outside. My personal thinking and idea I think this is general and very common case in Cambodia. (Linn, age 36)

Oh! That is the nature of men, you also knew about that. Example, we went to work at province, we can get some money, we ate something, and then went to KTV [Karaoke Television, a place where one can meet prostitutes] . . . most of men always had some partner with other girls. Especially, policemen. (Potan, age 43)

Actually this is not that difficult when we go out. We usually we go to the Bar, KTV, just sex and pay. So we don’t have to live with those girls, just keep it secret and don’t let our wife know, that’s it!! It just we can’t have 2 wives because of the financial problem. (Sothom, age 45)

Some men attributed men’s involvement with sex workers outside the home to a man’s dishonest personality and desire to have as many women as finances allow. They did not guarantee faithfulness and honesty to their wives, keeping their behaviors outside the home secret; as participants shared, “Men are not honest enough. I am bad and they are also bad, just same” (Makala, age 40); “Men always think that ‘Do not honesty to each other’ like Khmer proverbs saying. It is not enough only getting one woman and wants one more” (Potan, age 43). Even when they did not have enough money, the men reported the pursuit of women other than their wives as normal. One man justified visiting sex shops as better behavior than raping a child or hurting one’s wife.

Every man they are not that faithful enough and they are not that good. Some people raped a child, or even some young girl. However, we don’t have to do that. We can just find out those sex services. There are many places in Cambodia. Just pay them and come back home that’s ok. (Veasni, age 36)

In addition, 13 male participants confessed that they had sexual experiences around or before age 20 or before marriage. They would drink with friends and find a girl for sex, or had sexual relationships with girlfriends. One participant shared that, “Before married, I usually went for a walk and enjoyed sex and drinking” (Makala, age 40).

Masculinity: Membership in a Male Peer Group

Participants in this study primarily defined masculinity as membership in a male peer group. They believed that a real man knew how to get along with friends, drink, and sing, and had the ability to do what he wanted. When single, the participants reported spending their earnings on hanging out with friends, as one interviewee shared, “Sometime they asked me to hang out overnight to be a real man. If we can’t do that, we are not men” (Samik, age 29). They had friends who called, asked, and dragged them out to drink and to get girls.

When I was single, I was getting more money and more friends, they just took me to those places, but before that I am such a gentleman. I was a jeweller so I make pretty much money. I usually sent money to my parent. But my friends pulled me and I started drinking and got the girl. So, I never remained money in my pocket every month. (Makala, age 40)

“Being a man” also referred to strength for six study participants; in particular, they felt that a real man should be stronger than a woman and not act feminine, as one man shared, “For this actually it up to us, our manner, we act just like we are strong, that’s it! We have to be strong, just don’t act like a girl or gay, that’s it!!” (Sothom, age 45). Participants said that they often talked about their energy and pride as a man in a peer group when out drinking. One participant said, “When drinking, they always talked about their energy, their proudness, and their pride . . . summarize they are pride unlimited” (Seang, age 51).

Lack of Condom Usage in Marriage Prior to Diagnosis

Most participants had never used condoms with their wives before their or their wives’ HIV diagnosis. They mentioned decreased sexual feeling, no knowledge of condoms, and usage as a sign of spousal distrust as reasons for not using condoms during marital sexual relations. Men stated that condoms decreased their ability to get and keep an erection and felt unnatural. As one man stated, “For me, I don’t like to use [a] condom because it doesn’t feel good, not nature. Actually, when we use [a] condom it makes us just get no erection, just no feeling” (Sothom, age 45). The other main rationale for not using condoms was the lack of HIV and condom use information at the time participants married. They remembered the lack of HIV information prior to United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia, which in 1992, led to the restoration of peace after years of civil war. At that time, there was no broadcasting on the TV or radio about HIV or condom use.

At that time, there were not broadcasts about using condoms or about [the] new virus, so we did not know and we were not interested. There were not broadcasts on television about this virus. Right after UN came, we came to know. (Seang, age 51)

One participant who worked in Thailand and came back home about every 2 or 3 years assumed he got infected in Cambodia, complaining that Cambodia was late in protecting people from HIV. He remembered that condom use with commercial sex workers was a regulation in Thailand; if a man did not follow this law, he could not use the sex service. He practiced condom use when in Thailand because of that country’s regulations but did not in Cambodia, and hence became infected with HIV.

Condom use in a marital relationship is a trust matter between a husband and wife, according to the participants. A husband’s voluntary use of condoms with his wife would imply that he is afraid of being infected with HIV from her, giving her the perception that she was high-risk, like a sex worker. One man shared, “My wife, she is my sweetie. It is not good that I use condoms. With a sex worker, I can use a condom, because I am afraid of transmission viruses” (Kiseth, age 39). Some men felt that using a condom would make their wives suspect their love and trust. One man would not use condoms with his wife even as contraception.

I think the woman will doubt with the man when he uses a condom with her but in case of contraception the women can select the contraceptive pill, or just follow the natural way before and after ovulation, for the married couples. For me, I do not support using a condom. (Shivan, age 63)

Image of a Good Wife: Diligent and Loyal

The male participants reported that a wife who is diligent in being the family caretaker was their idea of a good wife. They expected their wives to stay at home doing housework, looking after children, and helping husbands: “She was just a lady and always stays at home. She looked after all children with a good care, and she did many house works” (Puklork, age 58).

Some study interviewees stated that a wife’s loyalty was very important; as one explained, “I wish to have a good wife that have a loyalty to me and especially don’t tell a lie to me. Those are enough for me” (Sithan, age 32). They wanted their wives to respect and trust them as life partners in any environment and situation. Having a good heart, being unaggressive, and being honest were also characteristics that the men wanted in their wives. One participant shared, “Being a good wife for me is beautiful, loyal, not that aggressive to me and to other, and friendly, something like that” (Borek, age 47).

Meaning of Sex: A Part of Life Pleasure

The meaning of sex for the men was summarized in four parts. First, according to participants, sex is a source of life pleasure and of men’s happiness. They liked sex because it provided them with feelings of joy, excitement, and general well-being. Second, for some of the men, sex itself was not useful or purposive, but participants reported seeking sex as part of their instinct and nature, one that could not be controlled or dismissed. One participant explained, “Sex is not useful, just makes feeling good at a moment, and then make us tired, but that is human basic need and human life” (Kiseth, age 39). Third, participants distinguished the meaning of sex with sex workers from that of sex with their wives. They valued sex with their wives as part of sharing mutual understanding, love, and happiness. One man confessed, “Actually, there are two types of sex. If we have sex with our wives and share happiness together because we know each other feeling clearly and that is happiness and feel comfortable” (Sothom, age 45). However, sex with a woman outside the marriage was considered necessary for feeling good in the moment due to sexual release, and the men viewed commercial sex workers as interested in just earning money.

Outside girl, those called prostitutes, they need only our money. They can’t remember who you are at the next day. She just says, “You just give money to me, and get out.” So they need only our money, it’s just nothing. (Veasni, age 36)

Last, some men implied that sex was only for having a child by ending their comments with phrases like “Nothing else besides having a baby,” “That’s enough,” “That’s all,” and “Just that, no more than children.”

Perspectives on Using Sexual Techniques: Useful but Only With a Sex Worker

Participants agreed that using techniques (e.g., woman on top position, woman playing with penis with her fingers) during sex had benefits. It stimulated their feelings as arousal and provided more excitement and higher satisfaction.

I believed that when [we] use techniques, we actually feel good. I don’t know the girl’s feeling because I am a man. I always wanted a lady to be satisfied and first reach to the goal by using our technique. But I do not know the woman feeling. I am 100% for sure for all men, they feel that. (Shivan, age 63)

However, participants felt they could use those techniques with sex workers but not with their wives. They felt they could request some sex techniques from sex workers because they are paid, but cannot hurt or force their wives into satisfying only the husbands. A man likened it to committing a sin against his wife: “When we do that with our wife, it is like to sin her” (Puklork, age 58). The men respected their wives as their spouses, not as prostitutes, and used only simple techniques because they thought their wives would not like anything else. “She does not like. If I know 15 styles, I can use just one style only with her. She never just follows my order” (Makala, age 40). Sex workers follow the men’s requests because of money, but the men felt that their wives did not need to please their husbands for money so the wives would not be open to different sexual techniques. In the men’s view, sexual techniques enhance sexual excitement for men but not for women, making it simply additional work for women.

Prostitutes, they will follow us [on] all techniques, because they want our money. For [a] wife, she doesn’t need fun. If my salary 1000$, I just give my wife 70 to 80% so she doesn’t need to do to please her husband. She knows that is her money. (Shivan, age 63)

Some men agreed that, if a woman knew how to use sexual techniques and agreed to use them with her husband at home, the husband would reduce his visits to sex shops. One participant stated it most clearly: “This is actually the most important part about us. If our wives are just good enough, we can’t go out to seek for those services of prostitutes” (Borek, age 47).

Purpose of Marriage: Children and Stability

Participants expected marriage to bring them a happy life through having children and enough money. Children were what the men most wanted from marriage. After that, stable family finances were a priority. Having enough money to purchase land, a big house, a car, and the things they wanted was considered a source of family happiness. They regarded making enough of an income to be rich as a responsibility of the head of household: “Yes! I had many dreams. I always wanted to build a big house and to buy a car” (Potan, age 43).

Discussion

This study reveals the social and cultural factors underlying Cambodian men’s perspectives in connection with risk opportunities of HIV infection in marriage.

This study’s findings illustrate that involvement with commercial sex workers generally occurs when a husband is drunk and/or forced to be far from home for a lengthy period of time. In other studies, male migration and mobility among married couples were factors encouraging HIV infection; in India, infection occurred 4.4 times more in men with a migration history than in their stationary counterparts and 2.3 times more for the wives of those migrating men (Saggurti, Mahapatra, Sabarwal, Ghosh, & Johri, 2012). This suggests that HIV prevention programs should include an intervention targeting men who are required to stay far from home for a certain period (e.g., 3 months). The program can introduce diverse leisure activities and educational HIV seminars as after-work events in the community to replace drinking and pursuing extramarital relationships. It is interesting that one participant justified using sex workers as a better choice than child rape. Child sex trafficking occurs in all Southeast Asian countries, and Cambodia is one of the most affected (Davy, 2014).

In this study, the men confessed that they were not honest or faithful to their wives, while women in previous studies perceived their husbands’ visits to sex shops as part of public business (just for fun, not for getting more women) and trusted their husband to be faithful (Yang et al., 2016). In a setting where HIV transmission occurs through heterosexual contact, behavioral change is most imperative. Male faithfulness as a method for protecting the family from HIV within a marriage has been mentioned as a preventive measure in a Mozambique study (Bandali, 2011), and divorcing an unfaithful spouse is suggested as a sensible HIV risk reduction strategy in a 2008 study (Reniers, 2008). Cambodian women generally do not have sex with anyone but their husbands, but most married men in that country have been with sex workers or have girlfriends outside of marriage (Yang, 2012). According to women infected with HIV from their husbands, the men are regretful and feel sorry about the spousal HIV transmission so they try to become better husbands by curtailing their infidelity after discovering both their and their wives’ HIV status (Yang, Lewis, & Wojnar, 2015). Thus, HIV interventions in Cambodia need to target HIV-negative couples and address the promotion of positive marital practices such as mutual respect, love, friendship, and faithfulness, rather than simply focus on safer sex behaviors within marriage (Mugweni, Pearson, & Omar, 2012).

Research suggests that cultural and societal expectations and norms of what constitutes a “real man” can create an environment where HIV transmission is a high risk. Men in this study reported making an effort to be approved as a member of their male peer group by joining in their friends’ drinking and visiting of sex shops. Moreover, concepts of masculinity may prevent men from acknowledging that they need more information about sex and sexually transmitted diseases, resulting in risky sexual experimentation to prove their manhood (Mane & Aggleton, 2001). In a previous study in Uganda, peer pressure was a sociocultural influence for adolescents making sexual decisions to fit in their peer group, saying “the others are doing it” (Katz et al., 2013). Thus, working with Cambodian male adolescents to change their perceptions of masculinity and to foster their ability to refuse friends’ requests to join them in inappropriate behavior may be an important long-term step in lowering HIV transmission in marriage. A junior and senior high school curriculum could be aimed at healthy gender norms and attitudes toward sex. Young men outside the education system should be included in community-based programs.

The interviewees reported they had no knowledge of HIV and had never used condoms with their wives before being diagnosed. The rate of condom use is low as both a contraceptive and an HIV prevention method in other countries too. For example, in an analysis using nationally representative cross-sectional surveys of women in 16 developing countries, only 2% of married couples used condoms for contraception (Ali, Cleland, & Shah, 2004). The majority of HIV-positive Thai men (73%) never used condoms with HIV-negative wives before disclosure, and a shorter duration of marriage (less than 2 years) and younger age (less than 30 years) were associated with HIV seroconversion (Rojanawiwat et al., 2009). Thus, newly married and young couples may be at higher risk of HIV transmission within a marital relationship. Kalipeni and Ghosh (2007) reported that people continued to not use condoms during intercourse even when they knew about the benefits of condom use (Kalipeni & Ghosh, 2007). Thus, future research needs to study what creates this gap between knowledge and behavior in a human being. Condom use in marriage may be socially acceptable to wives; however, in past studies, a Cambodian wife’s request for condom usage within marriage was often seen as a sign of her lack of trust in her husband (Yang et al., 2013). In contrast, the men in this study considered wanting to use condoms as a sign to their wives that the wives’ behavior was not trusted. This difference in the concepts of condom use and spousal trust may be attributed to a lack of communication between husbands and wives about sexual and relational issues. Previous studies have illustrated that Cambodian couples have poor marital communication about sexuality, instead choosing to talk mostly about daily, economic, and child issues (Yang, 2012). A woman’s economic and social reliance on her husband, her traditional role as nurturer and caregiver, and her inability to negotiate safe sex practices due to the cultural constraints in a male-dominated society emerged as hindrances to effective communication between couples in past studies (Patel et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2016). In Malawi, the idea of talking with one’s husband about using condoms during marital sex was likened to inviting an intruder into one’s house (Chimbiri, 2007). Therefore, efforts should be placed on removing the societal stigma of condom use in marriage and changing men’s attitude to voluntarily use condoms to protect their spouses. Programs also need to be developed that help women increase their decision-making autonomy in safe sexual relations as needed.

A 2013 study concluded that the concept of sexual obedience to one’s husband as part of an ideal Cambodian woman’s behavior often led to an increase in HIV-related risky behaviors within marriage (Yang et al., 2013); the men in this study did not address this sexual aspect, instead mentioning diligence in housework and loyalty to one’s husband as part of being a good wife. Some men in this study agreed that a woman’s use of a variety of sexual techniques with her husband may decrease the man’s extramarital sexual relations. Cambodian women often view sex only as work; they respond to their husbands when requested and are proud of their ignorance of various sexual techniques, seeing that as the providence of paid sex workers (Yang et al., 2016). Thus, it is strongly suggested that sex education programs targeting women be developed; the materials can include content discussing sex as a pleasurable activity to enjoy with one’s husband and how to satisfy oneself and one’s husband with certain techniques (e.g., doing contractions, squeezing, pushing and pulling the pelvic muscles during sex, trying sex with the woman on top).

In conclusion, efforts to change those factors that influence Cambodian men’s perspectives on gender roles, marital infidelity, masculinity, and condom use in marriage need to be changed; otherwise, it will be difficult to reduce their wives’ HIV risk. The findings of this study can guide couple-oriented prevention efforts. One of this study’s main strengths is that it is the first study exploring culturally embedded factors of HIV transmission from the perspective of Cambodian men in HIV-concordant couples. A major study limitation is the timing of the study; there is the possibility that perspectives changed after HIV diagnosis because the participants may have already undergone some changes in attitudes and behaviors while living with HIV. Another limitation could have occurred from using the previously developed model. Yang’s model guided the study well by informing in detail the topics dealt with in the study; however, it also may have limited the ability to find cultural factors that are absent in the model.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2015S1A5A8012848).

References

- Ali M. M., Cleland J., Shah I. H. (2004). Condom use within marriage: A neglected HIV intervention. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 82, 180-186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandali S. (2011). Norms and practices within marriage which shape gender roles, HIV/AIDS risk and risk reduction strategies in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique. AIDS Care, 23, 1171-1176. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimbiri A. M. (2007). The condom is an “intruder” in marriage: Evidence from rural Malawi. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 1102-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davy D. (2014). Understanding the complexities of responding to child sex trafficking in Thailand and Cambodia. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 34, 793-816. [Google Scholar]

- De Coninck Z., Feyissa I. A., Ekström A. M., Marrone G. (2014). Improved HIV awareness and perceived empowerment to negotiate safe sex among married women in Ethiopia between 2005 and 2011. PLoS ONE, 9(12), e115453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng S., Li Y., Mulsow M., Fischer J. (2010). Domestic violence against women in Cambodia: Husband’s control, frequency of spousal discussion, and domestic violence reported by Cambodian women. Journal of Family Violence, 25, 237-246. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9287-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Family Health International. (2002). Strong fighting: Sexual behavior and HIV/AIDS in the Cambodian uniformed services. Retrieved from http://www.aidsdatahub.org/sites/default/files/documents/FHI_2002_Cambodia_Sexual_Behavior_and_HIV_AIDS_in_the_Cambodian_Uniformed_Services.pdf

- Hong R., Chhea V. (2009). Changes in HIV-related knowledge, behaviors, and sexual practices among Cambodian women from 2000 to 2005. Journal of Women’s Health, 18, 1281-1285. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H.-F., Shannon S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalipeni E., Ghosh J. (2007). Concern and practice among men about HIV/AIDS in low socioeconomic income areas of Lilongwe, Malawi. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 1116-1127. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz I. T., Ybarra M. L., Wyatt M. A., Kiwanuka J. P., Bangsberg D. R., Ware N. C. (2013). Socio-cultural and economic antecedents of adolescent sexual decision-making and HIV-risk in rural Uganda. AIDS Care, 25, 258-264. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.701718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan T., Cole J., Leukefeld C. (2002). Women, sex, and HIV: Social and contextual factors, meta-analysis of published interventions, and implications for practice and research. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 851-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mane P., Aggleton P. (2001). Gender and HIV/AIDS: What do men have to do with it? Current Sociology, 49(6), 23-37. [Google Scholar]

- Marston C., King E. (2006). Factors that shape young people’s sexual behavior: A systematic review. Lancet, 368, 1581-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon A. K. (2003). Gendered epidemic: Addressing the specific needs of women fighting HIV/AIDS in Cambodia. Berkeley Women’s Law Journal, 18, 254-264. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Women’s Affairs. (2008). A fair share for women: Cambodia gender assessment. Retrieved from http://www.adb.org/documents/fair-share-women-cambodia-gender-assessment

- Mugweni E., Pearson S., Omar M. (2012). Traditional gender roles, forced sex and HIV in Zimbabwean marriages. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14, 577-590. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.671962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa K. (2006). More than white cloth? Women’s rights in Cambodia. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Cambodian Defenders Project. [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Authority. (2015). Cambodia Country Progress Report. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/KHM_narrative_report_2015.pdf

- National Center for HIV/AIDS Dermatology and STD. (2011). Annual Report. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Patel S. N., Wingood G. M., Kosambiya J. K., McCarty F., Windle M., Yount K., Hennink M. (2014). Individual and interpersonal characteristics that influence male-dominated sexual decision-making and inconsistent condom use among married HIV serodiscordant couples in Gujarat, India: Results from the positive Jeevan Saathi study. AIDS Behavior, 18, 1970-1980. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0792-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan H., Patterson L. (1994). Men are gold, women are cloth. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: CARE International in Cambodia. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney H. M. (2008). “Rice is essential but tiresome; you should get some noodles”: DoiMoi and the political economy of men’s extramarital sexual relations and marital HIV risk in Hanoi, Vietnam. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 650-660. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2007.111534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reniers G. (2008). Marital strategies for regulating exposure to HIV. Demography, 45, 417-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts J. (2009). Preventing spousal transmission of HIV in Cambodia: A rapid assessment and recommendations for action. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: UNIFEM, UNAIDS. [Google Scholar]

- Rojanawiwat A., Ariyoshi K., Pathipvanich P., Tsuchiya N., Auwanit W., Sawanpanylaert P. (2009). Substantially exposed but HIV-negative individuals are accumulated in HIV-serology-discordant couples diagnosed in a referral hospital in Thailand. Japanese Journal of Infectious Disease, 62(1), 32-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saggurti N., Mahapatra B., Sabarwal S., Ghosh S., Johri A. (2012). Male out-migration: A factor for the spread of HIV infection among married men and women in rural India. PLoS ONE, 7(9), e43222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield T., Connell R. W., Walker L., Wood J. F., Butland D. L. (2000). Understanding men’s health and illness: A gender-relations approach to policy, research, and practice. Journal of American College Health, 48, 247-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sok P., Harwell J. I., Dansereau L., McGarvey S., Lurie M., Mayer K. H. (2008). Patterns of sexual behaviour of male patients before testing HIV-positive in a Cambodian hospital, Phnom Penh. Sexual Health, 5, 353-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopheab H., Fylkesnes K., Vun M. C., O’Farrell N. (2006). HIV-related risk behaviors in Cambodia and effects of mobility. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 41(1), 81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopheab H., Saphonn V., Chhea C., Fylkesnes K. (2009). Distribution of HIV in Cambodia: Findings from the first national population survey. AIDS, 23, 1389-1395. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832cd95a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations & AIDS. (2014). The Gap Report. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Webber G., Edwards N., Amaratunga C., Graham I. D., Keane V., Ros S. (2010). Knowledge and views regarding condom use among female garment factory workers in Cambodia. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine & Public Health, 41, 685-695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. (2012). HIV transmission from husbands to wives in Cambodia: The women’s lived experiences (Doctoral dissertation). University of Washington, Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Lewis F. M., Kraushaar D. L. (2013). HIV transmission from husbands to wives in Cambodia: A systematic review of the literature. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15, 1115-1128. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2013.793403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Lewis F. M., Wojnar D. (2015). Life changes in women infected with HIV by their husbands: An interpretive phenomenological study. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 26, 580-594. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2015.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Lewis F. M., Wonjar D. (2016). Culturally embedded risk factors for Cambodian husband-wife HIV transmission. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 48, 154-162. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]