Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to estimate the prevalence of alcohol use among men living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy (ART) and examine the association of alcohol use and psychosocial variables on ART adherence. The study was a cross-sectional survey supplemented by medical records and qualitative narratives as a part of the initial formative stage of a multilevel, multicentric intervention and evaluation project.

Method:

A screening instrument was administered to men living with HIV (n = 3,088) at four ART Centers using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–consumption questions (AUDIT-C) to determine alcohol use for study eligibility. Alcohol screening data were triangulated with medical records of men living with HIV (n = 15,747) from 13 ART Centers to estimate alcohol consumption among men on ART in greater Mumbai. A survey instrument to identify associations between ART adherence and alcohol, psychosocial, and contextual factors was administered to eligible men living with HIV (n = 361), and in-depth interviews (n = 55) were conducted to elucidate the ways in which these factors are manifest in men’s lives.

Results:

Nearly one fifth of men living with HIV on ART in the Mumbai area have consumed alcohol in the last 30 days. Non-adherence was associated with a higher AUDIT score, consumption of more types of alcohol, and poorer self-ratings on quality of life, depression, and external stigma. The qualitative data demonstrate that non-adherence results from avoiding the mixing of alcohol with medication, forgetfulness when drinking, and skipping medication for fear of disclosure of HIV status when drinking with friends.

Conclusions:

As the demand for ART expands, Indian government programs will need to more effectively address alcohol to reduce risk and maintain effective adherence.

With a global prevalence of 36.9 million people living with HIV, it is estimated that 15.8 million people (42.8%) were accessing antiretroviral therapy (ART) in 2015 (UNAIDS, 2015). Although ART has transformed HIV from a fatal to a chronic health condition for those who have consistent access to medication, the disease still requires lifelong management and commitment to a challenging treatment regimen (Holstad et al., 2011). Adherence failure leads to multiple and serious negative consequences including transmission to others, failure of first-line medication, and more rapid transition to severe illness and death. Understanding factors that contribute to non-adherence and to improving adherence to ART are essential to both prevention of transmission and treatment.

Alcohol has been shown to be among the most common and significant contributors to ART non-adherence (Samet et al., 2004) and negatively affects the entire treatment cascade (Azar et al., 2010). Even with limited consumption (Nakimuli-Mpungu et al., 2012), alcohol has serious consequences for disease progression and transmission (Conigliaro et al., 2003; Krupitsky et al., 2005; Samet et al., 2004). In a meta-analysis, subjects using alcohol were twice as likely to report poor adherence to ART as compared with abstainers (Hendershot et al., 2009). Alcohol consumption can affect immunologic function (Goforth et al., 2004) and cause early death (Neblett et al., 2011). Among those on ART, alcohol use has been associated with lower CD4 cell counts and higher HIV viral loads (Baum et al., 2010; Hendershot et al., 2009; Samet et al., 2003); impaired memory, concentration, and physical movements (Nevid et al., 2006); negative encounters with healthcare providers (Kagee & Delport, 2010); and reinforcement of poor health behaviors (Ware et al., 2006).

Alcohol consumption among people living with HIV has been shown to have a strong relationship with factors associated with less adherence including higher internal and external stigma, poorer mental health status, limited social support, and substance use and abuse. People living with HIV reporting higher levels of HIV stigma were more likely to report poor adherence to their medications compared to those with lower levels of HIV stigma (Rintamaki et al., 2006). Social support and mental health have been documented as important factors affecting ART adherence (Achappa et al., 2013; Huynh et al., 2013; Langebeek et al., 2014). Substance use and smoking, which are frequent among people living with HIV, also link to poor ART adherence (King et al., 2012; Moreno et al., 2015; Nguyen et al., 2016; O’Cleirigh et al., 2015; Shuter & Bernstein, 2008).

HIV and Alcohol in India

Despite the relatively low prevalence of HIV (0.26%), India—with a population of almost 1.3 billion—has an estimated 2.1 million people living with HIV (UNAIDS, 2014), making it the country with the third largest number of cases in the world. The rollout of free governmental ART services in India began in 2004, somewhat later than in many other countries. By 2014, there were 425 ART Centers serving 726,824 people living with HIV, an estimated 31% of the total number of people living with HIV in the country (National AIDS Control Organisation, 2014).

Although India has worked to bring HIV under control, first through prevention and then through universal free treatment, the rate of alcohol consumption has skyrocketed in the past decade, and many studies have identified problem drinking in HIV-and STI-vulnerable populations (Mimiaga et al., 2011; Saggurti et al., 2008, 2010; Samet et al., 2010; Schensul et al., 2010a, 2010b; Singh et al., 2010; Sivaram et al., 2008; Verma et al., 2010; Yadav et al., 2014).

This article describes research conducted on alcohol-consuming men living with HIV in four ART Centers in urban areas in Maharashtra, a large western state having India’s third highest HIV prevalence rate. The objectives of the study are to (a) estimate the prevalence of alcohol use among people living with HIV on ART, (b) examine the impact of alcohol use on ART adherence, and (c) explore the associations of socio-behavioral and mental health factors with ART adherence.

Method

The data for this study were collected as a part of the Indo–U.S. research and intervention project titled, “Alcohol and ART Adherence: Assessment, Intervention and Modeling in India,” funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA; Grant No. U01AA021990-01; S. Schensul, J. Schensul, N. Saggurti, A. Sarna, MPIs; 2014–2019). The project involves a formative qualitative and quantitative data collection stage followed by interventions at the individual, group, and community levels applied sequentially in three centers in three cycles and as a package in a fourth center with a fifth center as a control. Comprehensive baseline and follow-up surveys, baseline CD4 and follow-up viral load testing (available only in the post-formative phase), and process monitoring and evaluation serve to measure outcomes.

Medical record data

Every person living with HIV registered for treatment at any governmental ART Center has a paper medical record (“White Card”) in which demographic data, side effects, opportunistic infections, and CD4 counts are entered by ART staff. One of the questions asked by ART counselors on initiation into treatment concerns “habit of alcohol use,” with boxes to be ticked for habitual, social, and never. Medical record data are entered into the National AIDS Control Organisation electronic database and was provided to the project for all 13 ART Centers in Mumbai, Thane, and Navi Mumbai in the State of Maharashtra providing services in 2014–2015. A total of 33,993 patient records, of which 25,006 were male, were received in the electronic database. Medical record data have been used to examine drinking behavior, changes in CD4 count, comorbidities, opportunistic infections, and side effects of medication.

Screening instrument

To identify eligible candidates in the study and to obtain an estimate of alcohol consumption prevalence among people living with HIV in the four ART Centers, a screening instrument was developed and implemented that included questions of age, length of time since diagnosis, time on ART, and alcohol consumption. Alcohol consumption was measured using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–consumption questions (AUDIT-C), comprising questions concerning ever consumed, in the past year, and in the last 30 days. Experienced and trained research investigators approached and conducted face-to-face interviews using the screener with as many men as possible waiting for medication pick-up at the ART Centers. During the formative research period, 3,088 people living with HIV were screened. Eligibility for inclusion into the in-depth interview and survey samples consisted of being age 18 or over, being on ART for 6 months or more, and having consumed alcohol at least one or more times in the last 30 days.

In-depth interviews

A purposive sample of 55 men, approximately 13 from each of the four ART Centers, was selected for in-depth interviews lasting 1 to 1.5 hours conducted by trained research investigators. These interviews, consistent with the overall project research model, addressed the understanding of people living with HIV regarding how they contracted the virus, the impact on their lives and on their families, the process of accessing testing centers, the referral to the ART Center, services received at the ART Center, social support, psychological well-being, comorbidities, alcohol use, the nature of their sexual behavior, their experience with ART, their understanding of their disease status, and the role of alcohol in their lives. Interviews were transcribed and entered into Atlas.ti (Version 7.0; Friese, 2013), and code categories were developed based on both the project research model and new issues that emerged from the interview text. Multiple project staff coded the text and checked for reliability. These procedures created consistency and integration between the qualitative and quantitative data with which to determine, as well as interpret, associations (Schensul, 1993).

Survey instrument

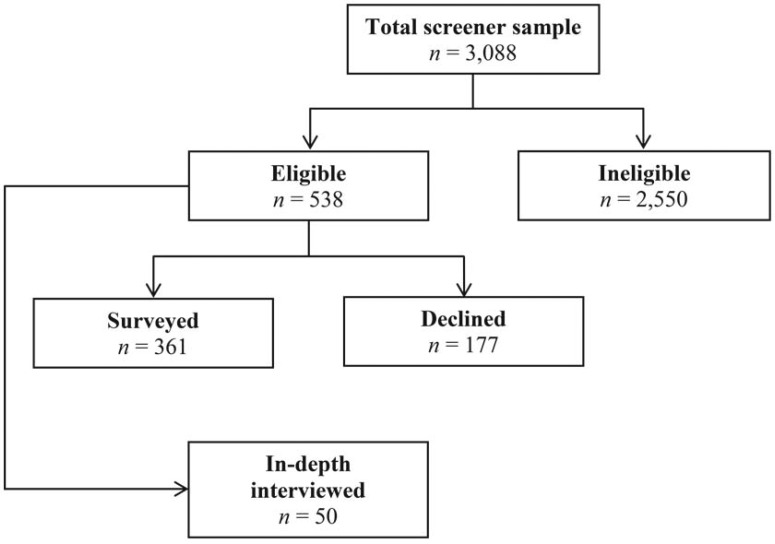

At the request of the Indian National AIDS Control Organisation, a preliminary survey instrument was developed to collect a broad range of data on alcohol and other variables as well as their impact on adherence and other outcomes. This survey instrument included both standardized scales and items derived from in-depth interviews and previous studies. The survey instrument was administered after medication pick-up to all eligible men living with HIV. Of the 3,088 who were screened, 538 (17.4%) people living with HIV were eligible for inclusion based on responses to the screener and written consent to participate. Of these 538 men, 177 (32.9%) indicated that they were not available to do the survey, 133 (75.1%) because they lacked the time to stay after they received their medication (most needing to get to work), 32 (18.1%) because they had no interest, and 12 (6.8%) who anticipated that they would be transferred to another Center (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the selection of participants in the study

The sociodemographic variables in the survey instrument included age, education level, marital status, religion, and employment and migration status.

Alcohol consumption was measured using the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) questionnaire developed by the World Health Organization (Saunders et al., 1993), which has been validated in India (Pal et al., 2004). The responses for each item were scored from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating more consumption and greater problems associated with alcohol use. The Cronbach coefficient α for this measure was .77. Poly-alcohol use was measured by asking about the types of alcohol consumed, comprising Indian-made whiskey, country liquor (desi daru), wine, and regular and strong (higher alcohol) beer.

Social support was measured using the 11-item Medical Outcomes Study social support scale (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991), which includes five dimensions: emotional support, informational support, tangible support, positive social interaction, and affection support. The total score ranges from 0 to 11, with higher scores indicating greater support. A family support component was assessed. The Cronbach coefficient α for this measure was .73.

Mental health was measured using (a) the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977), which has been validated in India (Cottler et al., 2010) (α = .70); (b) the EuroQol-5 Dimension covering five domains of health: mobility, self-care, main activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression (Brooks et al., 2003), which has been validated in India (Tripathy et al., 2015) (α = .73); (c) HIV-related self-stigma (16 items, α = .88) and HIV-related external stigma (20-item, α = .80), which have been developed for and validated in India (Steward et al., 2008); and (d) a tenshun scale (11 items, α = .80), developed and validated from ethnographic work in previous studies (Schensul et al., 2009). Tenshun, an Indian cultural concept drawn from the English “tension,” has entered common usage in the last decade to refer to chronic and situational anxiety, stress, and depression related to negative life events (Maitra et al., 2015).

ART adherence was assessed retrospectively based on a 4-day recall using the AIDS Clinical Trials Group instrument (Chesney et al., 2000). The non-adherence rate to ART was calculated by dividing the number of missed doses by doses prescribed (about two thirds were on a twice-per-day dosage and one third on a single dose) over a 4-day period.

Data analysis

Data were entered using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Univariate analysis was conducted to obtain descriptive statistics of all variables. The dependent variable was non-adherence rate to ART, which was treated as a count variable and was over-dispersed, indicating a non-normal variance of the data. Negative binomial regression was therefore used for the analysis (UCLA & the Statistical Consulting Group, 2016; Zwilling, 2013). To assess factors associated with non-adherence to ART, bivariate and multivariate negative binomial regression (Type I) analyses were conducted. The regression coefficient estimates have been exponentiated and reported as incidence rate ratios (IRRs; Drew et al., 2016; Stephens & Havens, 2013). The IRRs are a measure of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable (the percentage of missed ART doses) and are interpreted in the following way: A one-unit increase in the independent variable score is associated with n × the IRR effect on the dependent variable. All factors from bivariate analyses with probability values of .2 or less were included in the final multivariable model. A p value of < .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Before we conducted the multivariable negative binominal regression model, the correlations among the predictors and the outcome variable were examined for multicollinearity with the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). The values of VIF ranged from 1.1 to 1.4 indicating there was no significant multicollinearity among variables in the multivariate models.

The study was approved by the University of Connecticut Health Center Institutional Review Board, the India Council for Medical Research, the Health Ministry Screening Committee, National AIDS Control Organisation, and the institutional review boards of all collaborating agencies and hospitals. Written informed consent in Hindi or Marathi was obtained from all participants in the study.

Results

Assessing sample equivalence

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the screeners (n = 3,088). To determine if there was any selection bias among the study samples, analyses were conducted comparing the demographic characteristics between eligible (n = 538) and ineligible samples (n = 2,550) and between those who declined to respond to the survey (n = 177) and those who responded to the survey (n = 361).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Variable | Total screener sample (n = 3,088) M | Ineligible sample (n = 2,550) M | Eligible sample (n = 538) M | P | Declined sample (n = 177) M | Survey sample (n = 361) M | p |

| Age, in years | 41.8 | 41.8 | 41.8 | n.s. | 42.4 | 41.5 | n.s. |

| Education, in years | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.4 | n.s. | 7.6 | 7.3 | n.s. |

| Months since HIV diagnosed | 58.9 | 58.2 | 62.4 | n.s. | 67.0 | 60.1 | n.s. |

| Months since starting ART | 47.9 | 48.1 | 47.6 | n.s. | 50.4 | 46.3 | n.s. |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p | n (%) | n (%) | p | |

| Currently married | 2,512 (81.3) | 2,071 (81.2) | 441 (82.0) | n.s. | 143 (80.8) | 298 (82.5) | n.s. |

| Religion | |||||||

| Hindu | 2,683 (86.9) | 2,206 (86.5) | 477 (88.7) | n.s. | 157 (88.7) | 320 (88.6) | n.s. |

| Other | 405 (13.1) | 334 (13.5) | 61 (11.3) | 20 (11.3) | 41 (11.6) | ||

| Migration | |||||||

| Born in Mumbai | 1,170 (37.9) | 948 (37.2) | 221 (41.1) | n.s. | 85 (48.5) | 136 (37.7) | .014 |

| Born outside Mumbai | 1,918 (62.1) | 1,601 (62.8) | 317 (58.9) | 92 (52.0) | 225 (62.3) | ||

| Currently working | 2,639 (85.9) | 2,147 (84.2) | 492 (91.4) | <.001 | 158 (89.3) | 334 (92.5) | n.s. |

Notes: n.s. = not significant; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

As Table 1 shows, there were no significant differences in age, education level, months since diagnosis of HIV, months since starting ART, and marital status between the eligible and ineligible groups and between the declined and survey groups. The only differences were that the eligible group had a significantly higher level of current work status than the ineligible group, and those who responded to the survey reported a higher rate of having migrated to urban areas of Maharashtra than those who declined.

More than 85% of the total sample were working, indicating the efficacy of the ART in maintaining health. The educational range shows a wide spread indicative of the fact that “free medication” draws those of both higher and lower socioeconomic status. The means for both length of time since diagnosis and time on ART indicate that this is a population who for the most part are long-term users of HIV and ART programs. The low frequency of Muslims in the sample is because the ART Centers from which these samples are primarily drawn are located in urban areas outside of Mumbai, where the percentages of Muslims are lower.

Alcohol use prevalence

Analysis of the medical record data for the 13 ART Centers in urban Maharashtra shows that, of the 15,747 men living with HIV for whom there is data for this item, 6.4% (1,016) report themselves as “habitual” drinkers, 15.7% (2,471) report themselves as “social” drinkers, and 77.9% (12,260) report “never” drinking. If habitual and social are added together, the prevalence is 22.1%. Assessment of the medical records of 10,056 women living with HIV in the same 13 ART Centers indicated that only 86 (0.8%) had ever consumed alcohol, providing the rationale for the focus on men living with HIV only. There is limited consistency, however, in the way ART Center staff and respondents define these terms. In addition, medical records of 37% of the men living with HIV and 38.4% of the women living with HIV show missing data with regard to this question.

The screener uses the more reliable AUDIT-C to measure alcohol use. Although this screening sample is not random, it does represent a large number of people living with HIV at urban ART Centers and thus is the best approximation to date of the level of alcohol use among men living with HIV on ART in India. Table 2 presents the prevalence of alcohol use for the sample of 3,088 screeners.

Table 2.

Prevalence of alcohol use among the screeners

| Alcohol use | Positive, n (%) | Negative, n (%) |

| Have ever used alcohol | 2,123 (68.8) | 965 (31.3) |

| Used alcohol in the last year | 934 (30.2) | 1,191 (38.6) |

| Used alcohol in the last 30 days | 556 (18.3) | 369 (11.9) |

By combining the results of the medical record and the screener data, a conservative estimate suggests that approximately one fifth (18.3%) of men living with HIV have consumed alcohol at least once in the last 30 days.

Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy

The dependent variable of adherence is measured on the basis of reported missed doses in the last 4 days. For the total sample, 11.2% have missed at least one dose (less than 90% adherence) in this period. Using the survey data allows identification of the variables associated with adherence/non-adherence to ART. Table 3 provides the descriptive statistics for the predictor variables. Table 4 presents the results of the multivariate negative binominal regression analysis for the association between adherence to ART and alcohol, mental health, and social support variables.

Table 3.

Distribution of predictors

| Predictor variables | M (SD) | Range |

| AUDIT score | 7.9 (5.68) | 34.0 |

| Different types of alcohol | 1.3 (1.06) | 4.0 |

| Quality of life | 1.3 (0.31) | 0.9 |

| Depression (CES-D) | 0.3 (0.11) | 0.7 |

| Tenshun | 3.6 (1.06) | 4.7 |

| HIV-related external stigma | 0.5 (0.11) | 0.6 |

| HIV-related self-stigma | 2.5 (0.53) | 2.7 |

| Support from family | 0.5 (0.35) | 1.0 |

Notes: AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale.

Table 4.

Factors associated with non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in the past 4 days

| Characteristics | uIRR [95% CI] | p | aIRR [95% CI] | p |

| AUDIT score | 1.20 [1.16, 1.25] | <.001 | 1.19 [1.08, 1.16] | <.001 |

| Different types of alcohol | 2.43 [2.01, 2.96] | <.001 | 1.98 [1.57, 2.51] | <.001 |

| Quality of life | 5.43 [3.27, 9.05] | <.001 | 6.25 [3.57, 10.93] | <.001 |

| Depression (CES-D) | 2.15 [1.48, 3.13] | <.001 | 2.41 [1. 47, 3.94] | .001 |

| Tenshun | 1.14 [1.04, 1.25] | .004 | 0.78 [0.69, 0.87] | <.001 |

| External stigma | 10.49 [2.31, 47.77] | .002 | 4.66 [1.00, 21.68] | .043 |

| Self-stigma | 1.93 [1.56, 2.39] | <.001 | 0.65 [0.48, 0.87] | .005 |

| Support from family | 4.27 [3.02, 5.92] | <.001 | 3.81 [2.48, 5.85] | <.001 |

Notes: uIRR = unadjusted incidence rate ratio; aIRR = adjusted incidence rate ratio; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; CI = confidence interval; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale.

The results of the final negative binomial regression model show that people living with HIV who have a higher AUDIT score (i.e., they consumed more alcohol and experienced more associated problems) had significantly lower adherence to ART (IRR = 1.19, 95% CI [1.08, 1.16]). Consumption of more types of alcohol was significantly associated with lower adherence to ART (IRR = 1.98, 95% CI [1.57, 2.51]). Lower quality of life was significantly associated with decreased adherence to ART (IRR = 6.25, 95% CI [3.57, 10.93]). Contrary to hypothesized relationships, a higher level of tenshun was significantly associated with a higher adherence to ART (IRR = 0.78, 95% CI [0.69, 0.87]). Higher HIV-related external stigma was significantly associated with lower adherence to ART (IRR = 4.66, 95% CI [1.002, 21.68]). A higher level of HIV-related self-stigma was significantly associated with higher adherence to ART (IRR = 0.65, 95% CI [0.48, 0.87]). A higher level of family support was significantly associated with decreased adherence to ART (IRR = 3.81, 95% CI [2.48, 5.85]).

Qualitative data

More than half of the 50 men in the in-depth interviews reported that alcohol played an intimate role in their becoming HIV positive. The pattern involved drinking with friends, going to the “red-light” district, having sex with a sex worker without protection, and learning that they were positive through private HIV testing. Although some men had reported that they had stopped drinking once they heard the results of the testing or that the symptoms were sufficiently severe that they lost the desire to drink, most men who drank before their diagnosis continued the pattern after they initiated ART.

The in-depth interview data demonstrate that alcohol use, psychological factors, and social support all have an impact on ART adherence. In some cases these factors work independently of each other, and in others they are expressed together, showing a combined effect on an individual’s ART adherence. The direct relationship between alcohol use and adherence is often expressed in terms of forgetting to take doses of the medication when drinking or skipping doses purposefully because of a perception that the combination of alcohol and medication will render medication ineffective or be dangerous.

“I forget because of drink. Sometime I forget particularly morning doses due to rushing on work. If I drank whisky or rum, then purposely I do not take medicine to avoid any complication.” (Age 22, married, no children)

“Yes, when I drink that day I skip the medicine. I have a fear, if I take the medicine then it will have an effect on my health.” (Age 45, married, 4 children)

When combined with alcohol use, mental health issues such as depression, tenshun, and stress were described along with ART non-adherence.

“I know medicine is important for me. But because of much tenshun in my life, I forget to take the medication regularly . . . You can understand my drinking habit. If people have a lot of tenshun in family life then drinking will increase.” (Age 30, married, 1 child)

“I drink to forget this thing [HIV] which is happened with me. And I don’t want to blame anyone. Sometime I drink more so that time I prefer to not take the medicine.” (Age 41, married, 2 children)

“My family members always used to scold me [after drinking]. They say that you are suffering from a very dangerous disease and even then you are drinking, you should stop the drinking habit. One brother has gone (died) because of drinking alcohol. . .” (Age 35, married, 2 children)

Social support, particularly from spouses, is expressed in relation to ART adherence. This support often functions in practical terms for the men, transportation to ART centers, or picking up medication on their behalf. The emotional support provided by family is also described as invaluable.

“My family knew I was suffering from HIV, but they didn’t have any knowledge of this. And now they take care of me, and they always think about my health . . .” (Age 35, married, no children)

“I think I am getting love from all. Today my son was asking me whether I need him to accompany me to the ART Center. I felt very good when he asked me this.” (Age 48, married, 3 children)

Discussion

The screener data in combination with the medical records gave us the basis for estimating that nearly one fifth of the people living with HIV on ART in these urban ART Centers in the Western State of Maharashtra have consumed alcohol at least once in the last 30 days. This estimate is relatively consistent with other studies. A nationally representative sample of Indian households found that the prevalence of alcohol use among men in the previous 3 months was about 26% (Pandey et al., 2010). A study among 150 people living with HIV receiving ART at an HIV clinic in southwestern Uganda found that 21% reported consuming alcohol in the past 30 days (Bajunirwe et al., 2014).

Consistent with previous studies (Braithwaite et al., 2008; Hendershot et al., 2009; Parsons et al., 2008; Samet et al., 2004), the findings show that alcohol use was significantly associated with non-adherence to ART. Compared with earlier studies, however, the effect size of the AUDIT score on non-adherence to ART in our study was smaller, whereas the inclusion of a broader set of social and psychological independent variables and their effect sizes are larger than comparable studies reported in the literature (Achappa et al., 2013; Huynh et al., 2013; Langebeek et al., 2014). The findings of this study indicate that alcohol, in combination with social and psychological factors, plays a significant role in contributing to non-adherence among men living with HIV in India.

In the results of qualitative interviewing, men report a number of reasons for why alcohol interferes with adherence, including that they believe it does not “mix” well; that they “forget” when they drink; and that when they drink with friends, they do not want to be seen taking the medication and therefore have to disclose their status. Because a great majority of men work long hours, reluctance to disclose their status through taking medication is also a factor that interferes with adherence.

Alcohol use is not an isolated behavior but is deeply embedded in the social and psychological realities of people living with HIV on ART. External stigma, associated with fear of disclosure of one’s HIV status, along with a higher level of depression and a poorer quality of life, also contributes to poorer adherence. Contrary to hypothesized directions, however, people living with HIV who reported a higher level of tenshun, greater self-stigma, and less familial support showed higher levels of adherence. The qualitative data provide some assistance in sorting out the reasons for contrary results. People living with HIV experiencing more tenshun, greater self-blame, and internalized stigma described their greater adherence as their only coping strategy for “doing it to themselves.” The qualitative data indicate that people living with HIV who use greater amounts of alcohol make many demands on their families and although support may be high in general, the family makes less of a contribution to medication adherence as they deal with the needs and demands of people living with HIV in other areas.

These study results have limitations. The screener, medical records, and the survey were not drawn from randomly selected people living with HIV; as a result, they may suffer from nonrandom selection bias, although the size of the sample may increase confidence in its representatives. Self-reporting was used to measure adherence and alcohol use, which may be subject to social desirability and recall bias. Given the nature of a cross-sectional survey, a causal relationship among the study variables cannot be established.

It is clear that alcohol use in the context of an ART program must be reduced or eliminated for the health and well-being of the people living with HIV. A focus on alcohol use cannot be done, however, by simply passing on the message not to drink on a one-time basis. A comprehensive program needs to be established that can address the full range of factors, including not only alcohol and associated substances but also mental health, stigma, and social relationships that can increase the quality of life of people living with HIV.

Based on these formative research results, this NIAAA project has designed three multilevel interventions to be tested for their separate efficacy and their sequential impact. Individual counseling, consisting of four sessions provided by trained counselors, will particularly focus on the psychological factors of depression and tenshun that are associated with adherence and provide an impetus for alcohol use. Group intervention for 8–12 people living with HIV will focus on expanding knowledge of alcohol’s impact on adherence and mutual exchange of solutions for building positive social networks, improving quality of life, and reducing self-stigma. Community intervention aims to reduce the factors of external and internal stigma that undermine adherence through collective group action to address factors in the society that undermine the rights and services of people living with HIV and in turn empower individuals to more effectively address both alcohol and adherence. The consequences of the formative quantitative and qualitative research have directly led to the structuring and content of the interventions. Successive studies will report on the outcomes of these interventions in ameliorating the negative interaction of alcohol and ART adherence.

Acknowledgments

This project is a collaboration of the India offices of the Population Council and the International Center for Research on Women and the Network of Maharashtran Positive People (NMP+), the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, and the Institute for Community Research in Hartford, CT. We would like to acknowledge the project team with special thanks to the research investigators who so diligently and effectively collected the interview and survey data for this article.

Footnotes

This study was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant No. U01AA021990-01.

References

- Achappa B., Madi D., Bhaskaran U., Ramapuram J. T., Rao S., Mahalingam S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV. North American Journal of Medical. 2013;5:220–223. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.109196. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.109196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar M. M., Springer S. A., Meyer J. P., Altice F. L. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;112:178–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.014. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajunirwe F., Haberer J. E., Boum Y, II, Hunt P., Mocello R., Martin J. N., Hahn J. A. Comparison of self-reported alcohol consumption to phosphatidylethanol measurement among HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral treatment in southwestern Uganda. Plos One. 2014;9(12):e113152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113152. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0113152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum M. K., Rafie C., Lai S., Sales S., Page J. B., Campa A. Alcohol use accelerates HIV disease progression. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2010;26:511–518. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0211. doi:10.1089/aid.2009.0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite R. S., Conigliaro J., McGinnis K. A., Maisto S. A., Bryant K., Justice A. C. Adjusting alcohol quantity for mean consumption and intoxication threshold improves prediction of nonadherence in HIV patients and HIV-negative controls. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:1645–1651. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00732.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks R., Rabin R., de Charro F. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003. The measurement and valuation of health status using EQ-5D: A European perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney M. A., Ickovics J. R., Chambers D. B., Gifford A. L., Neidig J., Zwickl B., Wu A. W. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG Adherence Instruments. AIDS Care. 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. doi:10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conigliaro J., Gordon A. J., McGinnis K. A., Rabeneck L., Justice A. C. & the Veterans Aging Cohort 3-Site Study. How harmful is hazardous alcohol use and abuse in HIV infection: Do health care providers know who is at risk? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;33:521–525. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00014. doi:10.1097/00126334-200308010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler L. B., Satyanarayana V. A., O’Leary C. C., Vaddiparti K., Benegal V, Chandra P. S. Feasibility and effectiveness of HIV prevention among wives of heavy drinkers in Bangalore, India. AIDS and Behavior, 14, Supplement. 2010;1:S168–S176. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9729-5. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9729-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew D. A., Goh G., Mo A., Grady J. J., Forouhar F., Egan G., Swede H., Rosenberg D. W., Stevens R. G., Devers T. J. Colorectal polyp prevention by daily aspirin use is abrogated among active smokers. Cancer Causes & Control. 2016;27:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0686-1. doi:10.1007/s10552-015-0686-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese S. ATLAS.ti 7 user guide and reference. Berlin: Atlas ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. 2013 http://atlasti.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/atlasti_v7_manual_201312.pdf?q=/uploads/media/atlasti_v7_manual_201312.pdf

- Goforth H. W., Lupash D. P., Brown M. E., Tan J., Fernandez F. Role of alcohol and substances of abuse in the immuno-modulation of human immunodeficiency virus disease: A review. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment. 2004;3:174–182. doi:10.1097/01.adt.0000137432.11895.ee. [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot C. S., Stoner S. A., Pantalone D. W., Simoni J. M. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;52:180–202. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b18b6e. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b18b6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstad M. M., DiIorio C., Kelley M. E., Resnicow K., Sharma S. Group motivational interviewing to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications and risk reduction behaviors in HIV infected women. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15:885–896. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9865-y. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9865-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh A. K., Kinsler J. J., Cunningham W. E., Sayles J. N. The role of mental health in mediating the relationship between social support and optimal ART adherence. AIDS Care. 2013;25:1179–1184. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.752787. doi:10.1080/09540121.2012.752787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagee A., Delport T. Barriers to adherence to antiretroviral treatment: The perspectives of patient advocates. Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15:1001–1011. doi: 10.1177/1359105310378180. doi:10.1177/1359105310378180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King R. M., Vidrine D. J., Danysh H. E., Fletcher F. E., McCurdy S., Arduino R. C., Gritz E. R. Factors associated with nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive smokers. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2012;26:479–485. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0070. doi:10.1089/apc.2012.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupitsky E. M., Horton N. J., Williams E. C., Lioznov D., Kuznetsova M., Zvartau E., Samet J. H. Alcohol use and HIV risk behaviors among HIV-infected hospitalized patients in St. Petersburg, Russia. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.015. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langebeek N., Gisolf E. H., Reiss P., Vervoort S. C., Hafsteinsdottir T. B., Richter C., Nieuwkerk P. T. Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: A meta-analysis. BMC Medicine. 2014;12:142. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0142-1. doi:10.1186/s12916-014-0142-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maitra S., Brault M. S., Schensul S. L., Schensul J. J., Nastasi B. K., Verma R. K., Burleson J. A. An approach to mental health in low- and middle-income countries: A case example from urban India. International Journal of Mental Health. 2015;44:215–230. doi: 10.1080/00207411.2015.1035081. doi:10.1080/00207411.2015.1035081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga M. J., Thomas B., Mayer K. H., Reisner S. L., Menon S., Swaminathan S., Safren S. A. Alcohol use and HIV sexual risk among MSM in Chennai, India. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2011;22:121–125. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009059. doi:10.1258/ijsa.2009.009059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J. L., Catley D., Lee H. S., Goggin K. The relationship between ART adherence and smoking status among HIV+ individuals. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19:619–625. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0978-6. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0978-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakimuli-Mpungu E., Bass J. K., Alexandre P., Mills E. J., Musisi S., Ram M., Nachega J. B. Depression, alcohol use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:2101–2118. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0087-8. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-0087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Control Organisation. Annual report 2013-14. Retrieved from. 2014 http://www.aidsdatahub.org/annual-report-2013-14-national-aids-control-organisation-2014

- Neblett R. C., Hutton H. E., Lau B., McCaul M. E., Moore R. D., Chander G. Alcohol consumption among HIV-infected women: Impact on time to antiretroviral therapy and survival. Journal of Women’s Health. 2011;20:279–286. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2043. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevid J. S., Rathus S. A., Greene B. 6th ed. London, England: Pearson Education Ltd; 2006. Abnormal psychology in a changing world. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen N. T. P., Tran B. X., Hwang L. Y., Markham C. M., Swartz M. D., Vidrine J. I., Vidrine D. J. Effects of cigarette smoking and nicotine dependence on adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive patients in Vietnam. AIDS Care. 2016;28:359–364. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1090535. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1090535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Cleirigh C., Valentine S. E., Pinkston M., Herman D., Bedoya C. A., Gordon J. R., Safren S. A. The unique challenges facing HIV-positive patients who smoke cigarettes: HIV viremia, ART adherence, engagement in HIV care, and concurrent substance use. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19:178–185. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0762-7. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0762-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal H. R., Jena R., Yadav D. Validation of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in urban community outreach and de-addiction center samples in north India. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:794–800. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.794. doi:10.15288/jsa.2004.65.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J. T., Rosof E., Mustanski B. The temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and HIV-medication adherence: A multilevel model of direct and moderating effects. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2008;27:628–637. doi: 10.1037/a0012664. doi:10.1037/a0012664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A., Mishra R. M., Reddy D. C., Thomas M., Sahu D., Bharadwaj D. Alcohol use and STI among men in india: Evidences from a national household survey. Indian Journal of Community Medicine : Official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine. 2012;37:95–100. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.96094. doi:10.4103/0970-0218.96094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S. The CES-D scale. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar]

- Rintamaki L. S., Davis T. C., Skripkauskas S., Bennett C. L., Wolf M. S. Social stigma concerns and HIV medication adherence. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2006;20:359–368. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.359. doi:10.1089/apc.2006.20.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saggurti N., Schensul S. L., Singh R. Alcohol use, sexual risk behavior and STIs among married men in Mumbai, India. AIDS and Behavior 14, Supplement1. 2010:S40–S47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9728-6. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9728-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saggurti N., Verma R. K., Jain A., RamaRao S., Kumar K. A., Subbiah A., Modugu H. R., Halli S., Bharat S. HIV risk behaviors among contracted and non-contracted male migrant workers in India: Potential role of labor contractors and contractual systems in HIV prevention. AIDS, 22, Supplement. 2008;5:S127–S136. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000343771.75023.cc. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000343771.75023.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet J. H., Horton N. J., Traphagen E. T., Lyon S. M., Freedberg K. A. Alcohol consumption and HIV disease progression: Are they related? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:862–867. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000065438.80967.56. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000065438.80967.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet J. H., Pace C. A., Cheng D. M., Coleman S., Bridden C., Pardesi M., Raj A. Alcohol use and sex risk behaviors among HIV-infected female sex workers (FSWs) and HIV-infected male clients of FSWs in India. AIDS and Behavior, 14, Supplement. 2010;1:S74–S83. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9723-y. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9723-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet J. H., Phillips S. J., Horton N. J., Traphagen E. T., Freedberg K. A. Detecting alcohol problems in HIV-infected patients: Use of the CAGE questionnaire. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2004;20:151–155. doi: 10.1089/088922204773004860. doi:10.1089/088922204773004860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J. B., Aasland O. G., Babor T. F., de la Fuente J. R., Grant M. Development of The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schensul J. J., Singh S. K., Gupta K., Bryant K., Verma R. Alcohol and HIV in India: A review of current research and intervention. AIDS and Behavior, 14, Supplement. 2010a;1:S1–S7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9740-x. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9740-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schensul S. Using ethnograph to build a survey instrument. Cultural Anthropology Methods. 1993;5(2):9. doi:10.1177/1525822X9300500207. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1525822x9300500207?journalCode=fmxb. [Google Scholar]

- Schensul S. L., Saggurti N., Burleson J. A., Singh R. Community-level HIV/STI interventions and their impact on alcohol use in urban poor populations in India. AIDS and Behavior, 14, Supplement. 2010b;1:S158–S167. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9724-x. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9724-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schensul S. L., Verma R. K., Nastasi B. K., Saggurti N., Mekki-Berrada A. Sexual risk reduction among married women and men in urban India: An anthropological intervention. In: Hahn R. A., Inborn M., editors. Anthropology and public health: Bridging differences in culture and society. Second ed. 2009. pp. 362–394. Oxford Scholarship Online. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195374643.001.0001. [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne C. D., Stewart A. L. The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuter J., Bernstein S. L. Cigarette smoking is an independent predictor of nonadherence in HIV-infected individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:731–736. doi: 10.1080/14622200801908190. doi:10.1080/14622200801908190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. K., Schensul J. J., Gupta K., Maharana B., Kremelberg D., Berg M. Determinants of alcohol use, risky sexual behavior and sexual health problems among men in low income communities of Mumbai, India. AIDS and Behavior, 14, Supplement. 2010;1:S48–S60. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9732-x. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9732-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaram S., Srikrishnan A. K., Latkin C., Iriondo-Perez J., Go V. F., Solomon S., Celentano D. D. Male alcohol use and unprotected sex with non-regular partners: Evidence from wine shops in Chennai, India. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;94:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.016. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens D. B., Havens J. R. Predictors of alcohol use among rural drug users after disclosure of hepatitis C virus status. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:386–395. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.386. doi:10.15288/jsad.2013.74.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward W. T., Herek G. M., Ramakrishna J., Bharat S., Chandy S., Wrubel J., Ekstrand M. L. HIV-related stigma: Adapting a theoretical framework for use in India. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:1225–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.032. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy S., Hansda U., Seth N., Rath S., Rao P. B., Mishra T. S., Kar N. Validation of the EuroQol five-dimensions—Three-level quality of life instrument in a classical Indian language (Odia) and its use to assess quality of life and health status of cancer patients in Eastern India. Indian Journal of Palliative Care. 2015;21:282–288. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.164896. doi:10.4103/0973-1075.164896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UCLA & the Statistical Consulting Group. SPSS data analysis examples: Negative binomial regression. 2016 Retrieved from http://dev2.hpc.ucla.edu/stat/spss/dae/neg_binom.htm.

- UNAIDS. The gap report. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf.

- UNAIDS. Fact sheet 2015. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/campaigns/HowAIDSchangedeverything/factsheet.

- Verma R. K., Saggurti N., Singh A. K., Swain S. N. Alcohol and sexual risk behavior among migrant female sex workers and male workers in districts with high in-migration from four high HIV prevalence states in India. AIDS and Behavior, 14, Supplement. 2010;1:S31–S39. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9731-y. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9731-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware N. C., Wyatt M. A., Tugenberg T. Social relationships, stigma and adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2006;18:904–910. doi: 10.1080/09540120500330554. doi:10.1080/09540120500330554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav D., Chakrapani V, Goswami P., Ramanathan S., Ramakrishnan L., George B., Paranjape R. S. Association between alcohol use and HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men (MSM): Findings from a multi-site bio-behavioral survey in India. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18:1330–1338. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0699-x. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0699-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwilling M. Negative binomial regression. The Mathematica Journal. 2013;15:1–18. doi:10.3888/tmj.15-6. [Google Scholar]