Abstract

Objective:

The effectiveness of alcohol taxes in reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related problems is well established in research, yet increases in U.S. state alcohol taxes are uncommon. This study examined how alcohol tax increases occurred recently in three U.S. states, what public health’s role was, and what can be learned from those experiences.

Method:

Review of available documentation and news media content analysis provided context and, along with snowball sampling, helped identify proponents, opponents, and neutral parties in each state. Thirty-five semi-structured key informant interviews (lasting approximately 1 hour) were conducted, transcribed, and analyzed for common themes.

Results:

State routes to alcohol tax increases varied, as did the role of public health research. Use of polling data, leveraging existing political champions, coalition building, drawing on past experience with legislative initiatives, deciding revenue allocation strategically, and generating media coverage were universal elements of these initiatives. Tax changes occurred when key policy makers sought new revenue sources or when proponents were able to build coalitions broader than the substance abuse field.

Conclusions:

Translation of scientific evidence on the effectiveness of increasing alcohol taxes into public health interventions may occur if legislative leaders seek new revenue sources or if broad-based coalitions can generate support and sustained media coverage. Policy makers are generally unaware of the health impact of alcohol taxes, although public health research may play a valuable role in framing and informing discussions of state alcohol tax increases as a strategy for reducing excessive alcohol use and alcohol-related harms.

Excessive alcohol use is responsible for 88,000 deaths in the United States each year, including 1 in 10 deaths among working adults ages 20–64 and 4,300 deaths among those younger than age 21 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). It cost the United States $249 billion in 2010, or $2.05 per drink, including $24.3 billion in costs because of underage drinking (Sacks et al., 2015). Excessive alcohol use can lead to health effects from drinking too much over time (e.g., breast cancer, liver disease, and heart disease) and harms from drinking too much in a short period (e.g., violence, alcohol poisoning, and motor vehicle crashes) (World Health Organization, 2014).

Numerous scientific reviews have found that increasing alcohol taxes is an effective intervention for reducing excessive alcohol use and related harms, and the Community Preventive Services Task Force recommends increasing the unit price of alcohol by raising taxes based on strong evidence of effectiveness for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms (Babor et al., 2010; Elder et al., 2010; Wagenaar et al., 2009, 2010; World Health Organization, 2010). Yet, because most alcohol taxes are based on the volume of alcohol sold (i.e., are excise taxes), they do not rise with inflation and, therefore, lose much of their value if they are not regularly increased (Xuan et al., 2015). A number of state and local governments have introduced legislation to increase alcohol taxes in recent years, but most of this legislation has not passed. As a result, the value of state alcohol taxes has generally declined on an inflation-adjusted basis (Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, 2011, 2014).

The purpose of this article therefore is to analyze recent alcohol tax increases in three states (Illinois, Massachusetts, and Maryland) to answer two research questions: (a) What were the common elements of the alcohol tax initiatives in three states studied, and (b) what was public health’s role in these three tax initiatives and what can be learned?

Method

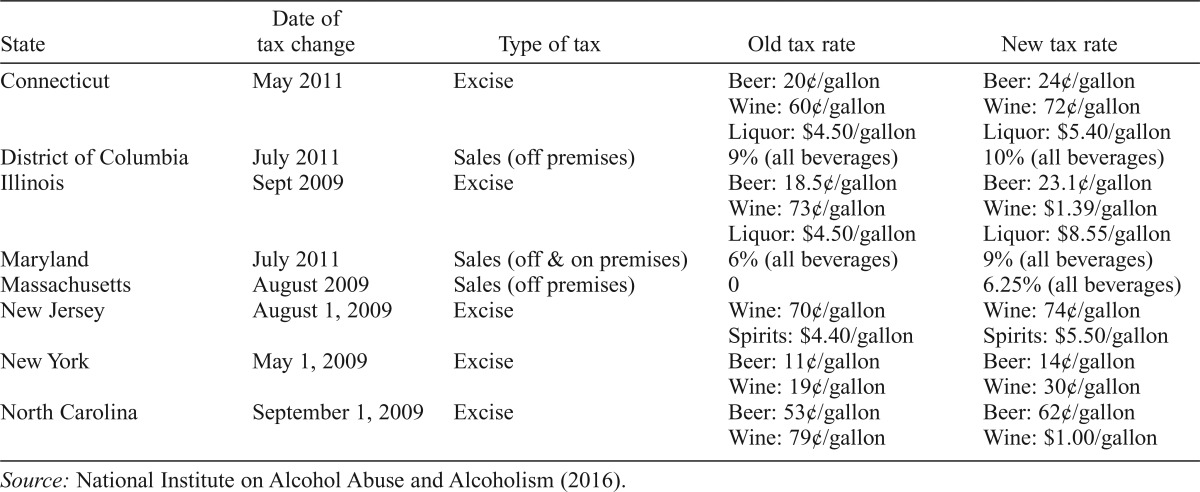

According to the Alcohol Policy Information System (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2016), seven states and the District of Columbia increased their alcohol taxes between 2009 and 2011 (Table 1). We selected the three with the largest changes that occurred across all three categories of beverages—beer, wine, and distilled spirits. From a preliminary review of public records, alcohol tax initiatives in these states—Illinois, Maryland, and Massachusetts—also illustrated a range of approaches for increasing alcohol taxes in states.

Table 1.

State alcohol tax changes, 2009–2011

| State | Date of tax change |

Type of tax | Old tax rate | New tax rate |

| Connecticut | May 2011 | Excise | Beer: 20¢/gallon | Beer: 24¢/gallon |

| Wine: 60¢/gallon | Wine: 72¢/gallon | |||

| Liquor: $4.50/gallon | Liquor: $5.4¢/gallon | |||

| District of Columbia | July 2011 | Sales (off premises) | 9% (all beverages) | 10% (all beverages) |

| Illinois | Sept 2009 | Excise | Beer: 18.5¢/gallon | Beer: 23.1¢/gallon |

| Wine: 73¢/gallon | Wine: $1.39/gallon | |||

| Liquor: $4.50/gallon | Liquor: $8.55/gallon | |||

| Maryland | July 2011 | Sales (off & on premises) | 6% (all beverages) | 9% (all beverages) |

| Massachusetts | August 2009 | Sales (off premises) | 0 | 6.25% (all beverages) |

| New Jersey | August 1, 2009 | Excise | Wine: 70¢/gallon | Wine: 74¢/gallon |

| Spirits: $4.40/gallon | Spirits: $5.50/gallon | |||

| New York | May 1, 2009 | Excise | Beer: 11¢/gallon | Beer: 14¢/gallon |

| Wine: 19¢/gallon | Wine: 30¢/gallon | |||

| North Carolina | September 1, 2009 | Excise | Beer: 53¢/gallon | Beer: 62¢/gallon |

| Wine: 790/gallon | Wine: $1.00/gallon |

Working from mentions of individuals in news media coverage, personal contacts, and recommendations from interviewees, we identified proponents, opponents, and neutral parties (e.g., journalists, pollsters, state employees) regarding the alcohol tax increases in each state. Because we were primarily interested in learning how alcohol tax increases were implemented, we focused more on proponents than opponents of the tax increases. However, we sought to interview at least one opponent and one neutral party in each state. Other materials—including voter information, press releases, talking points, written legislative testimony, legislation, and copies of media materials (radio or television), where available—were reviewed to obtain further information, including decisions about strategy, organization, and framing of messages.

We also collected a census of articles mentioning alcohol taxes from four leading newspapers in each state and performed content analyses of media coverage of efforts to raise alcohol taxes from January 1 of the year preceding the alcohol tax change through December 31 of the year after the alcohol tax change went into effect. The newspaper coding framework included both a priori questions and elements that emerged from initial review of the news data (Feraray & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). STATA Version 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) to calculate intercoder reliability (using Cohen’s κ) was used at the start of coding, halfway through coding the first state, and halfway through coding the remaining two states. Because the detailed methods used for the media content analyses are not central to this article, they are not reported here; where this article does include data from the content analysis, variables are only reported where concordance among the coders (κ) was greater than .70 (Viera & Garrett, 2005).

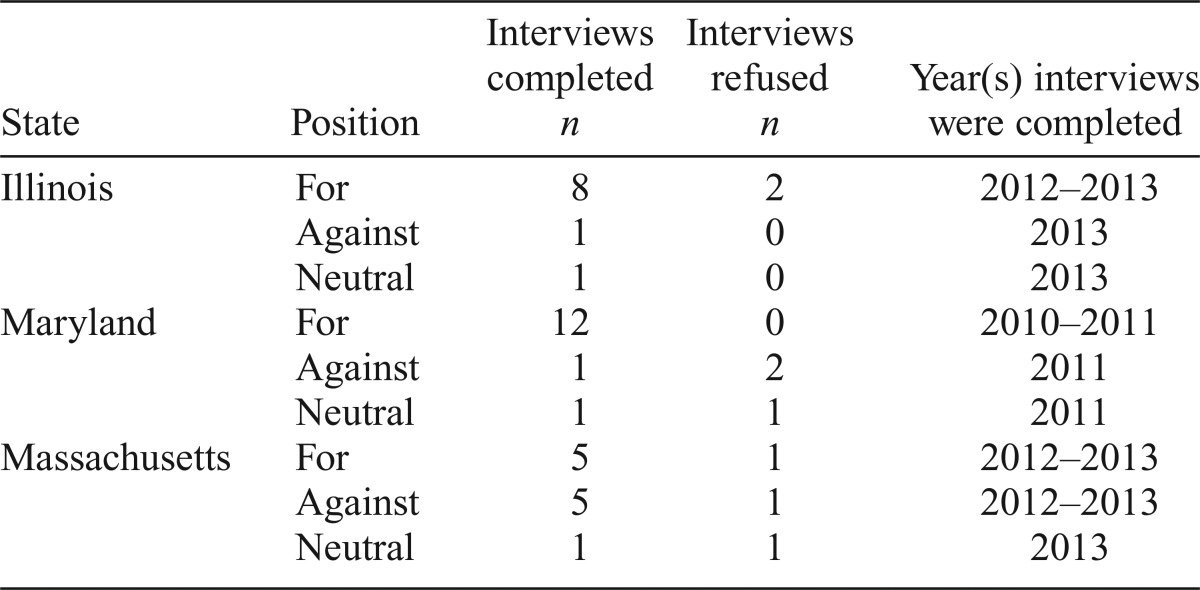

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with informants in each state (Table 2). Interviews in Illinois and Massachusetts were conducted at least 2 years after the tax increases occurred and in Maryland during the legislative process or within a year of the tax initiative. Interviews generally lasted less than an hour and drew from advocates, legislators, faith leaders, business owners, alcohol industry representatives, public health officials, and journalists. An interview guide (Table 3) was developed reflective of the two aims of the research: understanding how the campaigns happened and exploring the role of public health in them. Interview questions were selected from the guide based on each interviewee’s role in the tax effort. Interviewees subsequently received electronic versions of the interview transcript and could edit their responses before being included in this study.

Table 2.

Summary of interviews completed and refused

| State | Position | Interviews completed n |

Interviews refused n |

Year(s) interviews were completed |

| Illinois | For | 8 | 2 | 2012–2013 |

| Against | 1 | 0 | 2013 | |

| Neutral | 1 | 0 | 2013 | |

| Maryland | For | 12 | 0 | 2010–2011 |

| Against | 1 | 2 | 2011 | |

| Neutral | 1 | 1 | 2011 | |

| Massachusetts | For | 5 | 1 | 2012–2013 |

| Against | 5 | 1 | 2012–2013 | |

| Neutral | 1 | 1 | 2013 |

Table 3.

Interview guide (questions selected based on interviewee)

| 1. Please describe the nature of your job in general and a short description of your organization. |

| 2. What was your relationship to the initiative to raise alcohol taxes in [state] during the [year] legislative session? How did you and/or your organization participate in the campaign to raise alcohol taxes (i.e., please walk me through the entire process from start to end)? |

| 3. How did you decide that [year] was the year to advocate for the tax increase? What had happened in previous years to make you think that you had a good chance at getting a tax increase in [year]? |

| 4. From your perspective, what were the key phases of that campaign? Is there a specific strategy that you followed to get the tax passed? If so, please walk me through all the stages of your strategy. |

| 5. How familiar are you with the research on the potential public health benefits of raising alcohol taxes in reducing alcohol-related problems? What role do you think this research played in the campaign? |

| 6. Did you incorporate polling into your campaign? If so, when did you conduct polling, what were the outcomes, and how did you use them? |

| 7. How did you work with journalists to get your side of the story out there? Which newspapers/journalists do you feel did a good job of reporting the story? Were there local newspapers in key areas of the state that you targeted? What was the central message you were trying to get out through the news media, and how successful do you think you were at getting it out? What if any barriers did you encounter with the news media? |

| 8. Was there any paid media used during that time? If so, who paid for it and what was the message? |

| 9. What was your opinion of the section of the bill that dedicated new revenues generated by the tax increase to specific programs? |

| 10. Do you think dedicating these revenues to specific programs hurt or helped the bill’s chance for passage? Why? |

| 11. What in your view was the single most important factor shaping this campaign? |

| 12. If there was one piece of advice that you could go back and give yourself early on in the campaign, what would it be? |

| 13. Did other groups/individuals create a communications or organizing strategy to fight the ballot initiative? If so, who were they, how did they organize, and what were their primary messages? |

| 14. If you had to do it again, is there some strategy/event/approach that you would do differently? |

| 15. Who else do you think I should be talking with? |

A single interviewer conducted all interviews and coded the transcripts. Although researchers initially used QSR International’s NVivo software to identify nodes or themes that emerged from the interviews, ultimately the research team relied primarily on repeated review of the transcripts by hand, letting themes emerge from that review as in ethnographic content analysis (Altheide, 1996), in which themes are permitted to emerge from the data itself rather than being developed a priori. Once a set of themes had been identified, portions of interviews were then coded as relevant to those themes.

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that the research did not qualify as human subjects research and therefore did not require IRB oversight.

Results

Table 1 provides a summary of the tax laws enacted in each of these three case-study states. Of note, the newly applied sales tax increase in Massachusetts was subsequently repealed by a ballot initiative after only 1 year. Initial review of the interview transcripts generated a list of 23 themes; coding of the transcripts to these themes resulted in the identification of six common elements in the three state alcohol tax initiatives, as follows: (a) use of research, including public health data and resident polling; (b) political support; (c) coalition building; (d) past experience with legislative initiatives; (e) revenue allocation; and (f) media coverage.

Use of research

Public health data.

Awareness of research demonstrating that alcohol consumption and related harms decrease when prices increase (Wagenaar et al., 2009) and that youth are particularly sensitive to price changes (Chaloupka et al., 2002; Cook, 2007; Grossman et al., 1994) varied within the three states. At first in all three states, most stakeholders and partners were more interested in revenues that a tax increase could produce than potential effects on alcohol consumption and related harms. Describing an initial conversation on the proposed alcohol tax increase, a Maryland advocate stated, “They never talked about the independent public health benefits of raising the alcohol tax, or if at all, very little. They looked at it as a money source that would reduce alcohol problems by funding alcohol and drug programs. Many of the people in the coalition either didn’t know the research or didn’t believe it… it just wasn’t on their radar screen” (V DeMarco, interview, October 6, 2010).

However, after these initial conversations, the Maryland coalition made extensive efforts to put forward public health data on the impact of the proposed tax increase. Public health researchers prepared and released to the news media projections of the revenue and health effects of three different levels of tax increases. These projections showed that increasing taxes by the equivalent of 10 cents a drink could raise $214 million and decrease alcohol consumption by 4.79% (Jernigan & Waters, 2009).

Maryland was the only state of the three in which researchers provided a state-specific estimate of the number of lives that could be saved by an alcohol tax increase, from expected reductions in deaths from traffic crashes, homicides, and liver disease, as well as reductions in cases of assault, fetal alcohol syndrome, and alcohol dependence or abuse. The coalition also produced and wore buttons with the message, “Dime a drink saves lives.”

In Maryland, the opposition argued that the increase would cost the state jobs and would lead to cross-border shopping; the Massachusetts campaign encountered the latter argument as well. The Maryland campaign spanned two legislative sessions (2010 and 2011), and so in response to these arguments, it commissioned and released to the press a second report by public health researchers addressing the likely economic effects of the tax—including the impact on employment—as well as the cross-border shopping issue (Jernigan et al., 2011).

In Illinois, projections from an economist at the University of Illinois at Chicago estimated the revenue effects of doubling, tripling, or quadrupling the existing state alcohol excise tax, or increasing the tax by a nickel per standard drink. The latter option turned out to fall in between the doubling and tripling scenarios and was estimated to raise $254 million in revenue and decrease consumption of beer by up to 3.94%, wine by up to 2.5%, and distilled spirits by up to 6.7% (Heaps & Rooney, memorandum, February 17, 2009).

The coalition in Massachusetts used general public health research on the relationship between increases in alcohol prices and decreases in alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harms, without any Massachusetts-specific public health research on this relationship.

Role of state health departments.

Despite some use of public health data, with the exception of Massachusetts, state health departments played a minimal role in the three alcohol tax initiatives. Drawing on existing research, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health provided information on the general public health benefits of increasing the price of alcohol during public forums but did not provide any state-specific information on the expected impact of a state alcohol tax increase in Massachusetts.

Polling data.

Both Maryland and Massachusetts used polling to assess support for an alcohol tax increase, but in different ways. In Massachusetts, proponents of the tax increase added a few questions to an existing statewide poll in 2008 and found that approximately 58% of respondents would support taxing off-premises sales if revenues were dedicated to prevention and treatment. In addition to general opinion polling, proponents in Maryland used 501(c)4 funds (see below) to assess voting behavior in the upcoming 2010 general election and how this might change based on a candidate’s position on the proposed alcohol sales tax, a strategy the coalition had previously used to assess public support for handgun control (DeMarco & Schneider, 2000) and for an increase in state tobacco taxes (Jernigan, 2010). As one proponent stated, “When you have a vast majority of likely voters who through scientific polling say that they really support an alcohol tax . . . [whether] Republican or Democrat . . . being able to show legislators that voters will cross party lines [to support a candidate who favors the tax] is huge” (M. Celentano, interview, November 17, 2010).

Political support at outset

In Illinois and Massachusetts, politicians in each state showed early signs, either in the months preceding the legislative session or early on in the relevant legislative session, of willingness to support a tax increase. Proponents in Illinois knew that the senate president was an early supporter of increasing alcohol taxes for the general purpose of raising revenues. As one journalist who covered legislative affairs in Springfield noted, “A financing package is usually worked out among discussions of the top leaders, with the speaker and senate president and minority leaders. It’s not something that bubbles up from a rank and file member” (Anonymous Springfield, IL, journalist, January 31, 2013).

In Massachusetts, in the months immediately before the 2009 legislative session, proponents met with staff in the Executive Office of Health and Human Services and the Executive Office of Administration and Finance to obtain their support for the alcohol sales tax and their commitment to speak with the governor about it. Opponents in Massachusetts also noted the influence of the Senate Chairman of the Joint Legislative Committees on Taxation, who had advocated for years for repealing the alcohol exemption from state sales taxes.

In contrast, the Maryland efforts began without support from any of the key legislative leaders. In fact, then-Governor Martin O’Malley began his second term in 2011 by stating that he would not propose any new taxes on anything.

Coalition building

In all three states, small coalitions of alcohol prevention and treatment advocacy groups had spent years trying to educate legislative leaders about the potential public health impact of increasing alcohol taxes on excessive alcohol use and related harms. In Illinois and Massachusetts, these coalitions collaborated closely with legislators who expressed interest in raising the taxes in 2009. In Maryland, proponents of the alcohol tax increase formed a broader coalition—comprising public health, alcohol prevention and treatment, mental health, developmental disabilities, health care advocacy organizations, and labor unions—to propose an alcohol excise tax increase in 2009. Some of the members of this broader coalition had been working together for more than a decade on campaigns addressing a variety of public health issues, including tobacco, gun violence, and health care access.

In Illinois and Massachusetts, the coalitions comprised substance abuse prevention and treatment stakeholders. They wanted to ensure that any dedicated funds would be allocated to their cause and did not think there would be enough revenue generated by the tax to allow inclusion of other causes, issues, or partners. As one of the lead organizers in Massachusetts stated, “It’s really tough to get people to expend political capital if they’re not going to directly benefit from it. I totally get that.… We knew it wasn’t going to raise that much money so we really focused on saving money for addiction prevention and treatment programs” (V DiGravio, interview, 2012).

In Maryland, a broad and diverse coalition first negotiated among its members specific percentage splits for each constituency should the alcohol tax legislation pass. One lobbyist for alcohol prevention and treatment services recalled that an influential and supportive state senator suggested that proponents representing alcohol prevention and treatment enter into a partnership with the developmental disabilities community because, “The developmental disabilities folks are so well organized, are so vocal, and have extraordinarily compelling stories. They have spent many, many years working on their own advocacy” (A. Ciekot, interview, April 26, 2011). Other key constituencies that negotiated funds from the tax increase included alcohol and other drug as well as mental health service providers, a labor union representing health care workers, and a large statewide coalition seeking funding to support greater access to health care in the state.

A core group of four organizations—all nonprofits, but one being a 501(c)(4), a type of nonprofit with greater latitude for lobbying—conducted most of the organizing. They were joined by two large labor unions later in the campaign. One of the core organizations reached out to other groups across the state, including small businesses, faith-based organizations, and a variety of other constituencies with no direct interest in an alcohol tax. These groups supported an extension of health care benefits in the state that would be paid for by the additional alcohol tax revenues, and they generated signed resolutions from a diverse array of more than 1,200 organizations stating that they supported the tax increase.

Past experience with legislative initiatives

In each state, proponents had a long history of lobbying for increased resources for community services, but the substance abuse prevention and treatment groups had had little success in linking this lobbying to a revenue measure like an alcohol tax increase that could provide dedicated funding. In Illinois, the substance abuse prevention and treatment field had restored $55 million in proposed cuts during the budgetary process in 2008. In Massachusetts, a state senator had worked with proponents since the mid-1990s to increase alcohol taxes, but without success. Similarly, in Maryland, advocates in the substance abuse field had worked with supportive legislators to introduce an alcohol tax bill each year since the mid-1990s, also without success. However, the statewide healthcare coalition that led Maryland’s efforts to increase alcohol taxes had previously succeeded in raising the tobacco tax and changing gun laws during the late 1990s and 2000s.

Revenue allocation

Proponents of tax increases in all three states tried to dedicate at least a portion of the anticipated revenue to preventing and treating alcohol and other drug problems. In Illinois, substance abuse prevention and treatment advocates were unable to secure any resources for these services; all funds went to capital construction (roads and bridges) across the state. In Massachusetts, proponents initially secured budget language allocating 4.25% of the 6.25% sales tax (i.e., 68% of the anticipated revenues) to a newly created Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Trust Fund. In Maryland, only the developmental disabilities community received funds in the first year, with the balance of funds going for school construction and other educational activities, even though education advocates were not part of the original coalition. The Maryland legislature’s decision to dedicate much of the new alcohol sales tax revenue during the first year following the tax increase to school construction, which was very popular, weakened the opposition’s ability to lobby against it. As one industry lobbyist recalled, “I knew once they threw some bones to the developmental disability community and that they were going to include the school construction, that the bill was going to pass” (B. Bereano, interview, September 15, 2011).

All the tax proponents interviewed agreed that the general public tends to be more likely to support an alcohol tax increase if the funding is dedicated to worthy causes, such as healthcare services. On the other hand, the legislators interviewed in each state preferred to have the money go into the general fund so that they could allocate it, as needed, in the state budget. Economic conditions also helped convince state legislators in Illinois and Massachusetts to support alcohol tax increases, as both states faced significant budgetary challenges because of the recession of 2007–2009. As a result, interviewees from the alcohol and drug treatment community in Illinois reported thinking that, although their number one priority was securing funds for their sector, it was unlikely that new alcohol tax revenues would be used to support substance abuse prevention and treatment services. In Massachusetts, advocates were unable to sustain the dedicated revenues when the measure subsequently went to the ballot box; however, they were gratified that state legislators did not cut the overall budget for the Massachusetts Bureau of Substance Abuse Services even after the alcohol tax was repealed.

Maryland law required the proposed alcohol tax increase and allocation of the expected tax revenue to be in separate bills. One of the main organizers recalled during a legislative hearing “saying to our coalition that it’s OK if they pass the tax in one bill and allocate the funds separately . . . . It’s not as secure as the dedicated funds we want, but we have to deal with reality” (V DeMarco, interview, April 21, 2011). After its initial failure to gain the earmarks, the Maryland coalition regrouped and secured them in the next annual budget.

Media coverage

The proposed tax increases generated media coverage in all three states. Illinois had the least print coverage, with only 60 news articles mentioning the alcohol tax increase, compared with 239 in Maryland and 190 during the period up to the passage of the tax in Massachusetts. Putting these numbers into context, Massachusetts and Maryland are close in size in terms of population (Massachusetts: 6.5 million; Maryland: 5.8 million in 2010), whereas Illinois had 12.8 million residents in 2010 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017).

In Illinois, once it became clear that legislative leadership intended to pass an alcohol tax increase, state legislators and leading advocates held one press event in support of what was essentially a “placeholder” alcohol tax bill early on to show bipartisan support for increasing alcohol taxes and for giving some of the new tax revenue to substance abuse prevention. However, once the alcohol tax increase was folded into a larger capital spending bill, proponents elected not to push for media coverage.

In Massachusetts, although media attention played a role, much of the coverage was neutral in tone—that is, it did not seem to favor either side of the alcohol tax debate—and generally presented the alcohol tax increase alongside other proposed changes to the state budget rather than drawing attention to it as a separate tax proposal.

The Maryland coalition considered both earned and paid media as essential to their strategy to increase awareness and educate the public and legislators. Leaders in the coalition, including both advocates for increased health care access and advocates for persons with developmental disabilities, had long-established relationships with reporters and journalists and used them to promote the potential public health benefits of the proposed legislation. As one proponent described it, “We get coverage just to keep the issue in the spotlight as much as possible” (M. Celentano, interview, November 17, 2010). Another noted that their spokespersons were “very strong in knowing how to frame the message and put forth a positive response on the public health benefit” (B. Cox, interview, April 26, 2011).

Maryland’s legislature only meets for 90 days of each year, so much of the media advocacy and resulting attention occurred before the legislative session. One advocate reported that, “by the time you get to session, a lot of media attention [has been] paid every step of the way. Whenever there was a key point [about the tax increase], there was a lot of outreach to media, which generates more interest by the media. They didn’t get tired of the issue” (L. Howell, interview, May 26, 2011). Labor unions involved in the coalition paid for a radio message that played during key legislative discussions on the bill, encouraging voters to call their legislators and ask them to support the alcohol tax increase. Proponents continued their “public relations offensive” (V. DeMarco, interview, April 21, 2011) through the effective date of the tax, believing it important to show support for the tax increase and to highlight how the increased funding would benefit different constituencies across the state.

Discussion

Alcohol tax increases have the potential to serve two public health objectives. First and foremost, a large body of research has established that these tax increases can reduce excessive alcohol consumption and related problems (Elder et al., 2010; Wagenaar et al., 2009, 2010). Second, alcohol tax increases can provide additional revenues that may be used to fund public health priorities, including alcohol and other drug prevention and treatment.

In practice, the campaigns chronicled here struggled to achieve both of these objectives, and policy makers and key stakeholders alike were more interested in the latter than the former.

Although the research base supporting the effectiveness of increasing alcohol taxes as a public health intervention is robust, both decision makers and stakeholders in these states were for the most part unaware and skeptical that relatively modest tax increases would actually decrease excessive consumption and related problems. Subsequent evaluations of the Illinois and Maryland tax increases have demonstrated that they did precisely this (Esser et al., 2016; Staras et al., 2014, 2016; Wagenaar et al., 2015; Lavoie et al., 2017). The Maryland campaign made more concerted efforts to put public health research at the forefront of the campaign, including release of two reports as well as the use of a slogan that the tax increase would save lives. Public health departments were generally not involved in the three tax initiatives. This may have been because, at least in part, none of these states had health department staff specifically working on the epidemiology and prevention of excessive alcohol use.

Support of political leaders for the state tax initiatives and for the designated use of tax revenues for particular health programs varied considerably across the three states. In Illinois and Massachusetts, political leaders supported the tax initiatives at the beginning of these campaigns but did not consistently support the use of tax revenue for alcohol and other drug problems. Maryland had no such support at the outset and instead sought out multi-sectoral support (that is, support broader than the substance abuse field).

It is of interest that Maryland was the most successful in advancing the dual public health objectives of implementing the tax increase and increasing funding for the alcohol and other drug field. This suggests that building alliances across public health, treatment, and human services by trading some or much of the expected proceeds may lend a proposed tax increase a broader and more powerful base of support. The subsequent loss of the tax increase at the ballot box in Massachusetts underscores the point that coalitions solely encompassing the substance abuse field may be insufficiently broad to bring about a sustainable victory.

Polling played a key role in Maryland and in Massachusetts, not only in demonstrating public support for the tax increases, but also in educating decision makers about it. Media coverage helped educate the public about the tax increase to some degree in all states. Proponents of the tax increases also generally relied more heavily on earned than paid media. However, once again Maryland was an outlier, with more media coverage per population as well as some paid media. In comparison, there was very limited coverage in Illinois.

This study has several limitations. First, despite multiple attempts, we were unable to conduct interviews with many of the opponents of the alcohol tax increases in Illinois and Maryland. We were also unable to interview legislators in Illinois or journalists in Maryland or Massachusetts. However, we interviewed informants representing proponents, opponents, and neutral parties and thus were able to learn about both sides of the issue, in all three states.

Second, with the exception of Maryland, we collected background information and conducted personal interviews 2 to 3 years after the tax initiatives were completed, which may have compromised collection of key background information and introduced recall biases. It is possible that the opportunity to reflect in the interviews during the campaign assisted the Maryland campaign to improve its effectiveness; however, this is unlikely given the brief duration of the interviews and that the Maryland coalition was following an organizing formula it had previously used successfully to pass tobacco taxes and gun-control measures. In Massachusetts, it is also possible that the fact that interviews occurred after the tax was repealed may have influenced responses. In both cases, we sought to complement and as much as possible verify information obtained from personal interviews using archival documents and news media coverage from that time.

Third, it was generally not possible to interview subjects for more than an hour. As a result, some information on the tax initiatives was likely to have been excluded from the interviews. Fourth, the involvement of the second author as an advisor to the Maryland campaign could have biased the findings of the interviews. We attempted to mitigate this by having the first author, who had no involvement with the campaign, conduct all the interviews in all three states. Fifth, the validity of interview data was limited by the presence of the researcher during the data collection process and the subjective interpretation of the large volume of interview data. Analysis of available documents and news media coverage was used in an effort to mitigate these limitations.

Abundant public health research has demonstrated that increasing alcohol taxes can reduce excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. This article shows that states have used a variety of approaches to increase alcohol taxes. Broad-based coalitions that reach beyond substance abuse treatment and prevention, such as the one assembled in Maryland, may be more effective in securing adoption of an alcohol tax increase and raising funds for alcohol and other drug programming than one that is focused on substance abuse alone. Using the news media to publicize the public health aspects of alcohol tax campaigns, as was also done in Maryland, can also assist in framing the issue and keeping it on the public agenda. Other research has found that only 40% of the American public follows health news closely (Brodie et al., 2003); media advocacy techniques such as producing and releasing reports, holding press-worthy events, and seeking out and/or writing guest editorials in support of alcohol taxes, all of which were used in Maryland, may help the public health field to surmount this barrier (Wallack et al., 1999).

Finally, public health engagement and visibility in these campaigns were scarce, as evidenced by the limited involvement of public health departments as well as the difficulty in making a public health–based argument for the taxes even among those supportive of the increases. Very few states have dedicated capacity in alcohol epidemiology. Building and sustaining state public health capacity to document and prevent excessive alcohol use and related harms—and involving public health professionals in educating and informing coalitions and other partners about the public health impact of excessive alcohol use and evidence-based prevention strategies to address it—could improve the field’s ability to translate research supporting the effectiveness of alcohol taxes as a preventive strategy into public health practice.

Footnotes

This research was funded by contract number 200-2011-40800 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Altheide D. (1996). Qualitative media analysis (Qualitative Research Methods Series, 38). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Babor T. F., Caetano R., Casswell S., Edwards G., Giesbrecht N., Graham K. Rossow I. (2010). Alcohol: No ordinary commodity: Research and public policy (2nd ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie M., Hamel E. C., Altman D. E., Blendon R. J., & Benson J. M. (2003). Health news and the American public, 1996–2002. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 28, 927–950. doi:10.1215/03616878-28-5-927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) software. Retrieved from https://nccd.cdc.gov/DPH_ARDI/default/default.aspx

- Chaloupka F. J., Grossman M., & Safer H. (2002). The effects of price on alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems. Alcohol Research & Health, 26, 22–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook P. J. (2007). Paying the tab: The costs and benefits of alcohol control Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeMarco V., & Schneider G. E. (2000). Elections and public health [Editorial]. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 1513–1514. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.10.1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distilled Spirits Council of the United States. (2011). Distilled Spirits Council 2010 industry review. Retrieved from http://www.discus.org/assets/1/7/2010_DISCUS_Industry_Briefing.pdf

- Distilled Spirits Council of the United States. (2014). Distilled Spirits Council 2013 industry review. Retrieved from http://www.discus.org/assets/1/7/Distilled_Spirits_Industry_Briefing_Feb_4_2014.pdf

- Elder R. W., Lawrence B., Ferguson A., Naimi T. S., Brewer R. D., Chattopadhyay S. K., … Fielding J. E., & the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. (2010). The effectiveness of tax policy interventions for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38, 217–229. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser M. B., Waters H., Smart M., & Jernigan D. H. (2016). Impact of Maryland’s 2011 alcohol sales tax increase on alcoholic beverage sales. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 42, 404–411. doi:10.3109/00952990.2016.1150485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feraray J., & Muir-Cochrane E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using the matic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M., Chaloupka F. J., Saffer H., & Laixuthai A. (1994). Effects of alcohol price policy on youth: A summary of economic research. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 4, 347–364. doi:10.1207/s15327795jra0402_9 [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H. (2010). The DeMarco factor: Interview with a health policy advocate. Health Promotion Practice, 11, 306–309doi:10.1177/1524839910366377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H., & Waters H. (2009). The potential benefits of alcohol excise tax increases in Maryland. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H., Waters H., Ross C., & Stewart A. (2011). The potential economic effects of alcohol excise tax increases in Maryland. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie M.-C., Langenberg P., Villaveces A., Dischinger P. C., Simoni-Wastila L., Hoke K., & Smith G. S. (2017). Effect of Maryland’s 2011 alcohol sales tax increase on alcohol-positive driving. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53, 17–24. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2016). Alcohol Policy Information System. Retrieved from http://www.alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov

- Sacks J. J., Gonzales K. R., Bouchery E. E., Tomedi L. E., & Brewer R. D. (2015). 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49, e73–e79. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staras S. A., Livingston M. D., Christou A. M., Jernigan D. H., & Wagenaar A. C. (2014). Heterogeneous population effects of an alcohol excise tax increase on sexually transmitted infections morbidity. Addiction, 109, 904–912. doi:10.1111/add.12493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staras S. A., Livingston M. D., & Wagenaar A. C. (2016). Maryland alcohol sales tax and sexually transmitted infections: A natural experiment. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50, e73–e80. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). 2010 Census Interactive Population Search. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/2010census/popmap/ipmtext.php

- Viera A. J., & Garrett J. M. (2005). Understanding interobserver agreement: The kappa statistic. Family Medicine, 37, 360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar A. C., Livingston M. D., & Staras S. S. (2015). Effects of a 2009 Illinois alcohol tax increase on fatal motor vehicle crashes. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 1880–1885. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar A. C., Salois M. J., & Komro K. A. (2009). Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: A meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction, 104, 179–190. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02438.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar A. C., Tobler A. L., & Komro K. A. (2010). Effects of alcohol tax and price policies on morbidity and mortality: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 2270–2278. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.186007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallack L., Woodruff K., Dorfman L., & Diaz I. (1999). News for a change: An advocate’s guide to working with the media. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2010). Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/alcstratenglishfinal.pdf?ua=1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2014). Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/msb_gsr_2014_1.pdf?ua=1

- Xuan Z., Chaloupka F. J., Blanchette J. G., Nguyen T. H., Heeren T. C., Nelson T. F., & Naimi T. S. (2015). The relationship between alcohol taxes and binge drinking: Evaluating new tax measures incorporating multiple tax and beverage types. Addiction, 110, 441–450. doi: 10.1111/ add.12818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]