Abstract

Background

Impairment in activities of daily living is a major burden to both patients and caregivers. Mild impairment in instrumental activities of daily living is often seen at the stage of mild cognitive impairment. The field of Alzheimer’s disease is moving toward earlier diagnosis and intervention and more sensitive and ecologically valid assessments of instrumental or complex activities of daily living are needed. The Harvard Automated Phone Task, a novel performance-based activities of daily living instrument, has the potential to fill this gap.

Objective

To further validate the Harvard Automated Phone Task by assessing its longitudinal relationship to global cognition and specific cognitive domains in clinically normal elderly and individuals with mild cognitive impairment.

Design

In a longitudinal study, the Harvard Automated Phone Task was associated with cognitive measures using mixed effects models. The Harvard Automated Phone Task’s ability to discriminate across diagnostic groups at baseline was also assessed.

Setting

Academic clinical research center.

Participants

Two hundred and seven participants (45 young normal, 141 clinically normal elderly, and 21 mild cognitive impairment) were recruited from the community and the memory disorders clinics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital.

Measurements

Participants performed the three tasks of the Harvard Automated Phone Task, which consist of navigating an interactive voice response system to refill a prescription (APT-Script), select a new primary care physician (APT-PCP), and make a bank account transfer and payment (APT-Bank). The 3 tasks were scored based on time, errors, repetitions, and correct completion of the task. The primary outcome measure used for each of the tasks was total time adjusted for correct completion.

Results

The Harvard Automated Phone Task discriminated well between young normal, clinically normal elderly, and mild cognitive impairment participants (APT-Script: p<0.001; APT-PCP: p<0.001; APT-Bank: p=0.04). Worse baseline Harvard Automated Phone Task performance or worsening Harvard Automated Phone Task performance over time tracked with overall worse performance or worsening performance over time in global cognition, processing speed, executive function, and episodic memory.

Conclusions

Prior cross-sectional and current longitudinal analyses have demonstrated the utility of the Harvard Automated Phone Task, a new performance-based activities of daily living instrument, in the assessment of early changes in complex activities of daily living in non-demented elderly at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Future studies will focus on cross-validation with other sensitive activities of daily living tests and Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers.

Keywords: activities of daily living, Alzheimer’s disease, longitudinal, mild cognitive impairment, performance-based

Introduction

Impairment in activities of daily living (ADL) is clinically meaningful to both patients and caregivers as it reflects difficulties in functioning and is associated with physical, psychological, and financial burden, as well as a loss of autonomy. While ADL impairment has been traditionally associated with the stage of dementia, mild impairment in instrumental ADL also occurs at the stage of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and has been incorporated into the revised diagnostic MCI criteria [1–3]. As the field of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) moves toward earlier diagnosis and intervention at the preclinical stage, more sensitive and ecologically valid assessments of instrumental or complex ADL are needed [4, 5].

We recently reported our initial experience with the Harvard Automated Phone Task (APT), a novel performance-based ADL instrument, which consists of navigating an interactive voice response system (IVRS) to perform common tasks required of elderly in their daily life [6]. We found that the Harvard APT discriminates well between young normal (YN), clinically normal (CN) elderly, and MCI participants and provides an incremental level of difficulty between tasks. Within CN elderly, the Harvard APT has a good short interval test-retest reliability and stability. Lastly, within CN elderly, the Harvard APT has a significant cross-sectional association with executive function, processing speed, and regional cortical atrophy independent of hearing acuity, motor speed, age, education, and premorbid intelligence.

In the current study, we aim to further validate the Harvard APT as a sensitive ADL test that could be used as an outcome measure in preclinical and early prodromal AD clinical trials and eventually even in clinical practice. Our objectives were to expand our sample in order to demonstrate stronger diagnostic group discrimination within non-demented individuals, and to assess the longitudinal relationship of the Harvard APT with global cognition and specific cognitive domains. We anticipate that the Harvard APT will be able to measure mild ADL changes that correspond with mild cognitive decline within CN elderly and MCI, which will support its potential use as a sensitive ADL outcome measure for early AD clinical trials.

Methods

Participants

Two hundred and seven participants were recruited from the community, the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) memory disorders clinics, and the Massachusetts Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (MADRC). Participants included 45 YN, 141 CN elderly, and 21 amnestic MCI. The 45 YN participants, 127 out of the 141 CN participants, and 10 of the 21 MCI participants overlap with the participants described in our previous study [6]. Moreover, new longitudinal data is presented in 23 CN and 10 MCI participants. All participants were healthy (other than having a diagnosis of MCI for those particular participants) or had stable chronic medical conditions and did not have active major psychiatric disorders.

YN participants were ages 18 to 27 years old (inclusive), had a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [7] score of 27 to 30 (inclusive), and normal memory performance (defined as a Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) [8] free recall score of >24 and cued recall score of >44). CN participants were ages 60 to 90 years old (inclusive), had an MMSE score of 25 to 30 (inclusive), and normal memory performance (FCSRT free recall score of >24 and cued recall score of >44). MCI participants were ages 61 to 90 (inclusive), had an MMSE score of 24 to 29 (inclusive), and impaired memory performance (FCSRT free recall score of ≤24 and/or cued recall score of ≤44).

The study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to initiation of any study procedures in accordance with Institutional Review Board guidelines.

Clinical Assessments

As previously described, the Harvard APT was developed at the BWH and MGH Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment and the Partners HealthCare Connected Health Innovation [6]. The Harvard APT consists of navigating an IVRS to complete the following 3 tasks: 1) Refilling a prescription (APT-Script); 2) Calling a health insurance company to select a new primary care physician (APT-PCP); and 3) making a bank account transfer and payment (APT-Bank). APT-Bank was developed later than APT-Script and APT-PCP. Therefore, fewer participants underwent APT-Bank. It takes about 10 minutes to complete all 3 tasks.

Tasks are scored based on total time (until disconnected), number of errors, number of repetition of steps, and correct completion of task. The primary outcome measure used for each of the tasks is total time adjusted for correct completion—for participants who did not complete the task correctly, time was adjusted to reflect that with greater resulting time values (they were assigned a total time equivalent to the longest total time among individuals who correctly completed the task). This adjustment was made because there were problems in the interpretation of raw time scores when participants gave up on the task too early or thought that they were done but did not compete the task correctly. In such cases, the raw time may have underestimated the participant’s impairment. Therefore, an adjusted time score may be more appropriate for more impaired individuals, which is especially relevant for follow-up assessments.

We developed alternate versions of the 3 tasks with equivalent psychometric properties for test-retest reliability and in order to minimize practice effects from year to year.

Other clinical assessments used in the current study included the American National Adult Reading Test intelligence quotient (AMNART IQ) [9], an estimate of premorbid intelligence; the MMSE [7], a measure of global cognition; the FCSRT [8], a measure of episodic memory; Trailmaking Test A (TMT-A) [10], a measure of processing speed; and Trailmaking Test B (TMT-B) [10], a measure of executive function.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 and SAS version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC). Demographics and participant characteristics provided in Table 1, including performance on cognitive testing, were related to the Harvard APT tasks in the overlapping smaller sample as previously reported [6]. The results of the cross-sectional association of the Harvard APT with participant demographics and characteristics within the current larger sample are similar and are therefore not shown.

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics of all participants.

| YN | CN | MCI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 45 | 141 | 21 |

| Age (years) | 21.4±2.3 (18–27) | 73.9±7.1 (60–90) | 77.2±8.2 (61–90) |

| Sex (% Female) | 71.1 | 73.1 | 42.9 |

| Race (% White) | 73.3 | 76.9 | 95.2 |

| Education (years) | 14.4±1.6 (12–18) | 16.1±2.9 (5–20) | 17.0±1.9 (14–20) |

| AMNART IQ | 122.0±4.5 (111–131) | 121.5±9.3 (80–132) | 121.8±8.3 (99–131) |

| MMSE | 29.7±0.7 (27–30) | 29.0±1.2 (25–30) | 27.3±1.7 (24–29) |

| FCSRT free recall | 38.6±3.5 (28–46) | 33.1±4.5 (25–47) | 15.1±8.3 (3–24) |

| FCSRT cued recall | 47.9±0.3 (47–48) | 47.8±0.5 (46–48) | 36.6±11.9 (13–48) |

| TMT-A (sec) | 20.7±5.9 (12–36) | 39.5±15.4 (12–95) | 38.8±16.3 (16–72) |

| TMT-B (sec) | 45.7±10.9 (27–68) | 93.3±48.4 (26–300) | 105.8±57.5 (41–230) |

AMNART IQ (American National Adult Reading Test intelligence quotient), CN (clinically normal elderly), MCI (mild cognitive impairment), MMSE (Mini-Mental State Exam), FCSRT (Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test), TMT (Trailmaking Test), YN (young normal).

Values represent mean ± standard deviation (except for n, Sex, and Race).

In MCI participants, reliability of the Harvard APT (APT-Script and APT-PCP) was determined with intraclass correlations and inter-item correlations. Test-retest was performed with a short interval (17.6±8.7 days) using an alternate version. For CN participants, test-retest reliability analyses were previously described [6].

Discrimination between diagnostic groups (YN, CN, and MCI) was performed cross-sectionally on the baseline portion of the data used below for the longitudinal analyses, employing a general linear model after log transforming adjusted time for Task 1 (APT-Script), yielding less skewed residuals. The main effect test for diagnostic group was followed by pairwise post-hoc tests using the Tukey-Kramer adjustment for multiple comparisons. For Task 2 (APT-PCP) and Task 3 (APT-Bank), which did not have normal distributions, the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test was used instead, followed by pairwise Mann-Whitney post-hoc tests.

Longitudinal analyses were run with respect to time (years) into the study for the dependent variables of the APT-Script and APT-PCP adjusted time in separate analyses. The predictors of primary interest were: MMSE, TMT-A, TMT-B, FCSRT free recall, and FCSRT cued recall, in separate analyses. Mixed fixed and random effects regression models were used with a backward elimination algorithm (p<0.05 cut off) on an initial pool of fixed predictors and variances/covariances of random terms. The linear component of time in the study was the relevant time predictor in all models. All models also initially included the fixed predictors of the baseline predictor of interest (MMSE, TMT-A, etc.), the final follow-up measure of the same variable, and the interactions of each with time. The term for the initial predictor was not removed from the model before those for the follow-up terms for interpretive reasons. The coefficients for the follow-up terms indexed change across the study in the given predictor given that the initial predictor value was statistically held constant. Additional covariates were baseline age and years of education. Random terms were participant intercepts and the linear slope term for Time in Study, initially allowed to be correlated. Residuals from values predicted by the fixed terms, as well as residuals from values predicted by the combination of both the fixed terms and random terms were checked for model fit and conformance to assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity.

Results

Test-retest reliability

Data was obtained for APT-Script and APT-PCP in MCI participants using the alternate versions over a short interval. Five participants underwent an alternate version after 17.6±8.7 days, yielding a intraclass correlation of 0.79 and an inter-item correlation of 0.66.

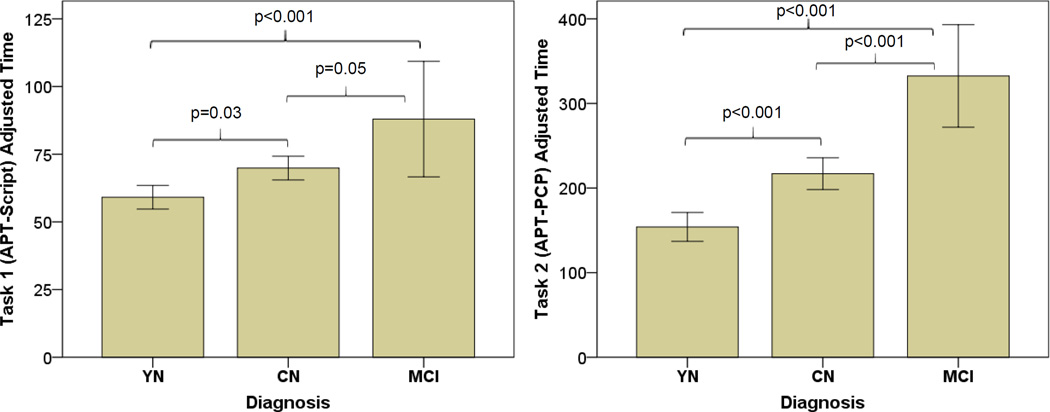

Discrimination between diagnostic groups

For Task 1 (APT-Script) and Task 2 (APT-PCP), there were significant differences among groups (APT-Script: p<0.001, APT-PCP: p<0.001) with MCI performing worse than CN (APT-Script: p=0.05, APT-PCP: p<0.001) and CN performing worse than YN participants (APT-Script: p=0.03, APT-PCP: p<0.001) (see Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2.

Performance on Harvard APT Tasks 1 and 2.

| Phone Tasks | YN | CN | MCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 45 | 141 | 21 | |

|

Task 1: APT-Script |

Adjusted Time (sec) |

59.1±14.5 (40– 118) |

69.9±26.4 (41–180) | 88.0±46.9 (48–180) |

| Errors | 0.3±0.6 (0–3) | 0.4±0.8 (0–6) | 0.6±1.0 (0–3) | |

| Step repetition | 0.1±0.3 (0–1) | 0.3±0.5 (0–3) | 0.6±0.7 (0–2) | |

| Completed (%) | 100 | 98.6 | 95.2 | |

|

Task 2: APT-PCP |

Adjusted Time (sec) |

154.1±56.7 (114– 480) |

217.0±113.0 (119– 480) |

332.5±129.5 (157– 480) |

| Errors | 0.9±1.5 (0–6) | 1.7±2.2 (0–8) | 4.2±2.8 (1–13) | |

| Step repetition | 0.4±0.5 (0–1) | 0.6±0.8 (0–3) | 1.2±1.5 (0–5) | |

| Completed (%) | 97.8 | 88.7 | 65.0 | |

APT (Automated Phone Task), CN (clinically normal elderly), MCI (mild cognitive impairment), YN (young normal).

Values represent mean ± standard deviation (range) except for n and Completed. There were significant differences between groups on adjusted time (Task 1: p<0.001, Task 2: p<0.001) with MCI performing worse than CN and CN worse than YN subjects.

Figure 1.

Bar graphs with error bars of adjusted time for Task 1 (APT-Script) (LEFT) and Task 2 (APT-PCP) (RIGHT) in YN, CN, and MCI participants. MCI performed worse than CN and CN performed worse than YN participants on both tasks. P values are corrected for multiple comparisons. APT (Automated Phone Task), CN (clinically normal elderly), MCI (mild cognitive impairment), YN (young normal).

Sixty-two (10 YN, 43 CN, and 9 MCI) of the 207 participants underwent Task 3 (APT-Bank). There were significant differences among groups (p=0.04), with MCI performing (non-significantly) worse than CN (p=0.29) and CN performing worse than YN participants (p=0.05).

Longitudinal analyses

33 CN and MCI subjects underwent 2 to 4 administrations of the Harvard APT over 2.4±0.8 years, as well as 2 assessments (baseline and final) of global cognition (MMSE), processing speed (TMT-A), executive function (TMT-B), retrieval memory (FCSRT free recall), and storage memory (FCSRT cued recall). Results of mixed effects models adjusting for age and education are described below.

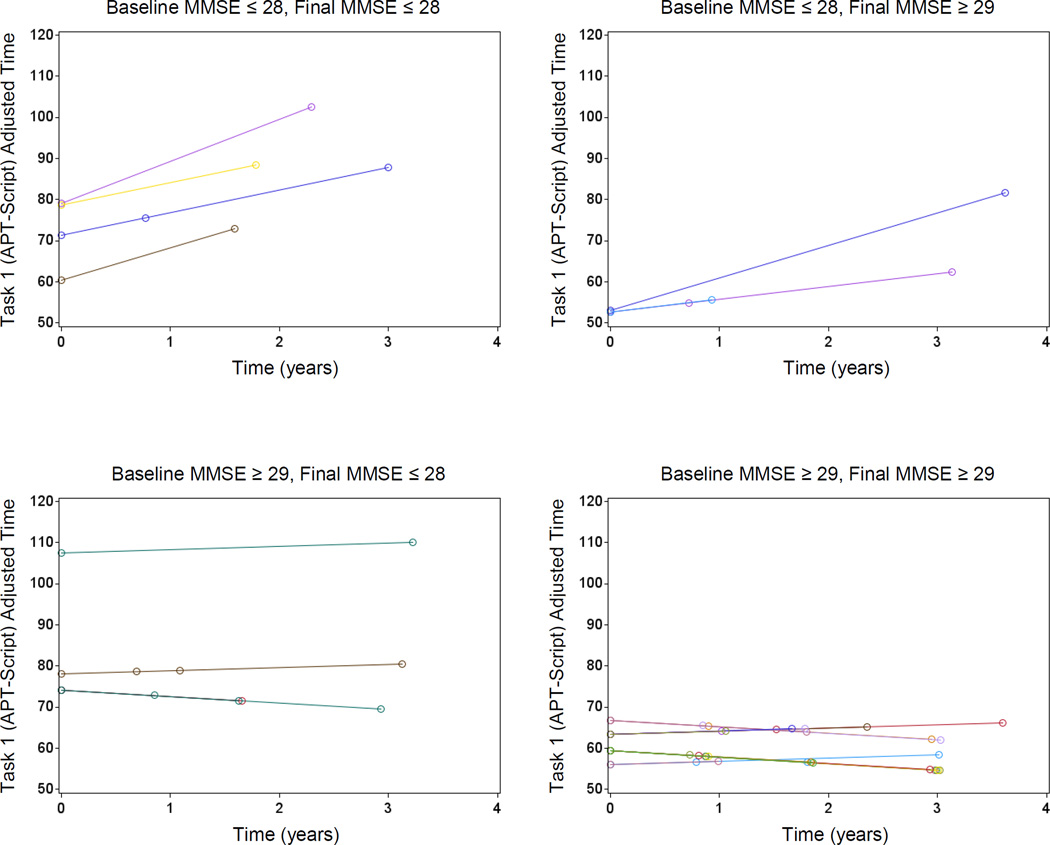

MMSE

Worse baseline global cognition was associated with worsening ADL over time (APT-Script: p=0.04; APT-PCP: p=0.03). Furthermore, worsening global cognition across time was associated with overall worse ADL (APT-Script: p=0.01; APT-PCP: p=0.01) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Predicted Values for APT-Script adjusted time from the fixed predictors of the mixed effects model, for individual participants, stratified by baseline/final and high/low (above/below the mean) MMSE score. Note that a baseline high MMSE score makes the slopes of APT-Script adjusted time shallower, whereas a final high MMSE score makes the lines lower. Within panel intercept/slope variation is due to variation in MMSE scores remaining within the indicated broad strata corresponding to the panels. APT (Automated Phone Task), MMSE (Mini-Mental State Exam).

TMT-A

Worse baseline processing speed was associated with overall worse ADL (APT-Script: p<0.001).

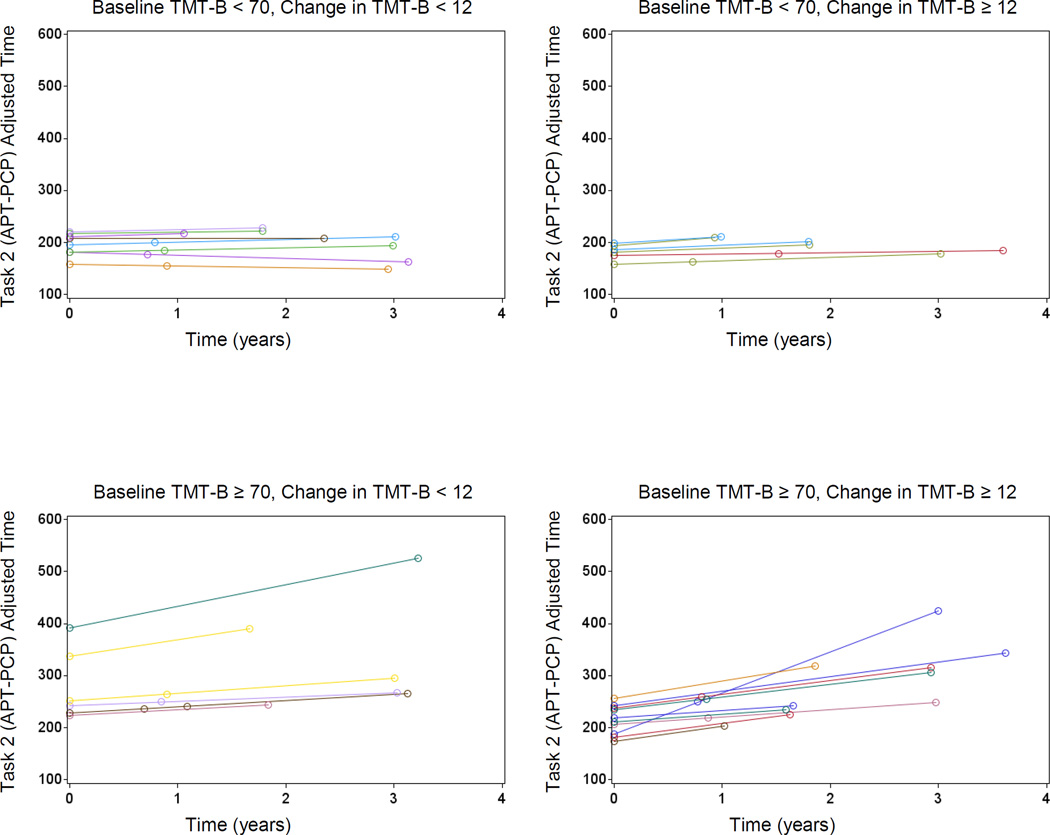

TMT-B

Worse baseline executive function was associated with overall worse ADL (APT-Script: p<0.001; APT-PCP: p=0.03). Greater decline from baseline to final executive function was associated with greater worsening of ADL over time (APT-PCP: p=0.04) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Predicted Values for APT-PCP adjusted time from the fixed predictors of the mixed effects model, for individual participants, stratified by baseline TMT-B score (high/low score according to a median split) and change in TMT-B score. Note that a baseline high TMT-B score and/or a greater change in TMT-B score (from baseline to final score) is associated with higher scores and a steeper increase over time of APT-PCP adjusted time. Within panel intercept/slope variation is due to variation in TMT-B scores remaining within the indicated broad strata corresponding to the panels. APT (Automated Phone Task), TMT (Trailmaking Test).

FCSRT free recall

Greater decrease in retrieval memory was associated with overall worse ADL (APT-Script: p=0.002). Worse baseline memory was marginally associated with worsening ADL over time (APT-PCP: p=0.07).

FCSRT cued recall

Worse baseline storage memory was associated with overall worse ADL (APT-Script: p<0.001). Greater decline from baseline to final storage memory was associated with greater worsening of ADL over time (APT-PCP: p=0.02).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that within CN elderly and individuals with MCI the new sensitive performance-based ADL test, the Harvard APT, tracks well over time with global cognitive function and specifically with processing speed, executive function, and episodic memory. Moreover, as we have previously shown [6], we now demonstrate more clearly with a larger sample size that the Harvard APT discriminates well between young and old clinically normal individuals and those with MCI.

Few ADL tests have been able to show functional decline in parallel with cognitive decline over time prior to the stage of dementia, and even fewer have been able to do so when starting with CN elderly at baseline [4]. Recently a longitudinal study in CN elderly of a hybrid scale assessing both subjective cognitive concerns and subjective ADL changes, the Cognitive Function Instrument (CFI), predicted cognitive decline over time [11]. In the current study, a subset of participants was followed for two and a half years with multiple administrations of the Harvard APT and cognitive tests. We were able to show that either worse baseline performance or worsening performance over time on the Harvard APT tracks well with overall worse performance or worsening performance over time in global cognition, processing speed, executive function, and episodic memory.

A few sensitive subjective and performance-based ADL tests have been able to discriminate well between CN elderly and MCI [12–14]. Similarly, we were able to clearly distinguish between CN and MCI participants using the Harvard APT, especially using the challenging APT-PCP task, in which individuals are asked to navigate a health insurance phone menu in order to select a new primary care physician.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently provided guidance for early AD clinical trial outcome measures [15]. For secondary prevention trials focused on individuals starting with preclinical AD, the recommendation is to have a single sensitive cognitive test as the primary outcome measure, which years later should be followed up by an ADL measure. This recommendation was made in light of the lack of sensitive ADL measures for individuals transitioning from preclinical to prodromal AD. To address this gap in the field, recommendations for such a sensitive ADL measure have been suggested, focused on using a performance-based instrument that assesses complex ADL that includes time and accuracy scores [5]. The short form of the Financial Capacity Instrument (FCI-SF) has shown subtle financial skill decline in individuals with preclinical AD participating in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, demonstrating the utility and feasibility of a performance-based ADL outcome measure for clinical trials in preclinical AD [16]. Our data with the Harvard APT suggests that it too could be helpful in assessing ADL changes at this early stage.

The current study had several limitations. First, our sample was highly educated and intelligent, which is common in convenience samples for observational studies and clinical trials. However, there was a wide range of education in the large CN group (5 to 20 years) and a little over a quarter were minorities. Second, our subset of participants with longitudinal data was small (n=33). However, the results were consistent across multiple cognitive tests. Third, we did not compare the Harvard APT to other sensitive ADL tests. The focus of the current study was to assess the longitudinal properties of the Harvard APT in relation to standard cognitive tests. We plan to report results relating the Harvard APT to several other ADL tests in a separate study.

In conclusion, we have previously shown that the Harvard APT is a sensitive tool for assessing early ADL changes in CN elderly and individuals with MCI who may be at the early stages of AD, focusing on cross-sectional comparisons to cognitive tests and test-retest reliability within the CN group. We now demonstrate acceptable to good reliability of the instrument in MCI, show improved ability to discriminate between CN and MCI, and most importantly, show that the Harvard APT is a good measure of complex ADL changes over time that corresponds with the progression of early cognitive decline over time. These properties of the Harvard APT, as well as its ecological validity, easy and quick administration (about 10 minutes altogether), make it a promising candidate as an ADL outcome measure for preclinical and early prodromal AD clinical trials. In future studies, we will cross-validate the Harvard APT with other sensitive ADL measures and determine its relationship to AD biomarkers at the preclinical stage of AD.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank RipRoad for their assistance in the development of the Harvard APT.

Funding

This study was supported by K23 AG033634, R01 AG027435, K24 AG035007, the Harvard Aging Brain Study (P01 AGO36694, R01AG037497, and R01 AG046396), the Alzheimer’s Association (SGCOG-13-282201), the Massachusetts Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P50 AG005134), and the Harvard NeuroDiscovery Center.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Marshall has served as a consultant for Halloran and GliaCure. Ms. Aghjayan, Ms. Dekhtyar, Dr. Locascio, Dr. Jethwani, Dr. Amariglio, and Dr. Johnson have no disclosures. Dr. Sperling has served as a consultant for Merck, Eisai, Janssen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Isis, Lundbeck, Roche, and Genetech. Dr. Rentz has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly, Neurotrack, and Lundbeck.

References

- 1.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall GA, Rentz DM, Frey MT, et al. Executive function and instrumental activities of daily living in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris JC. Revised Criteria for Mild Cognitive Impairment May Compromise the Diagnosis of Alzheimer Disease Dementia. Arch Neurol. 2012 doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.3152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall GA, Amariglio RE, Sperling RA, Rentz DM. Activities of daily living: Where do they fit in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2012;2:483–491. doi: 10.2217/nmt.12.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marson D. Investigating functional impairment in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2015;2:4–6. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2015.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall GA, Dekhtyar M, Bruno JM, et al. The Harvard Automated Phone Task: new performance-based activities of daily living tests for early Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2015;2:242–253. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2015.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grober E, Sanders AE, Hall C, Lipton RB. Free and cued selective reminding identifies very mild dementia in primary care. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24:284–290. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181cfc78b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson HE, O'Connell A. Dementia: the estimation of premorbid intelligence levels using the New Adult Reading Test. Cortex. 1978;14:234–244. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(78)80049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reitan RM. Validity of the trail making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amariglio RE, Donohue MC, Marshall GA, et al. Tracking early decline in cognitive function in older individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease dementia: the ADCS-Cognitive Function Instrument. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:446–454. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galasko D, Bennett DA, Sano M, Marson D, Kaye J, Edland SD. ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: assessment of instrumental activities of daily living for community-dwelling elderly individuals in dementia prevention clinical trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:S152–S169. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213873.25053.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg TE, Koppel J, Keehlisen L, et al. Performance-based measures of everyday function in mild cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:845–853. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09050692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triebel KL, Martin R, Griffith HR, et al. Declining financial capacity in mild cognitive impairment: A 1-year longitudinal study. Neurology. 2009;73:928–934. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b87971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozauer N, Katz R. Regulatory innovation and drug development for early-stage Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1169–1171. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1302513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marson DC, Gerstenecker A, Triebel K, et al. 19th Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. Toronto, Canada: 2016. Detecting functional impairment in preclinical Alzheimer's disease using a brief performance measure of financial skills. [Google Scholar]