Abstract

Purpose

The goal of this study is to summarize trends in rates of adverse events attributable to acetaminophen use, including hepatotoxicity and mortality.

Methods

A comprehensive analysis of data from three national surveillance systems estimated rates of acetaminophen-related events identified in different settings, including calls to poison centers (2008–2012), emergency department visits (2004–2012), and inpatient hospitalizations (1998–2011). Rates of acetaminophen-related events were calculated per setting, census population, and distributed drug units.

Results

Rates of poison center calls with acetaminophen-related exposures decreased from 49.5/1000 calls in 2009 to 43.5/1000 calls in 2012. Rates of emergency department visits for unintentional acetaminophen-related adverse events decreased from 58.0/1000 emergency department visits for adverse drug events in 2009 to 50.2/1000 emergency department visits in 2012. Rates of hospital inpatient discharges with acetaminophen-related poisoning decreased from 119.8/100 000 hospitalizations in 2009 to 108.6/100 000 hospitalizations in 2011. After 2009, population rates of acetaminophen-related events per 1million census population decreased for poison center calls and hospitalizations, while emergency department visit rates remained stable. However, when accounting for drug sales, the rate of acetaminophen-related events (per 1 million distributed drug units) increased after 2009. Prior to 2009, the rates of acetaminophen-related hospitalizations had been slowly increasing (p-trend = 0.001).

Conclusions

Acetaminophen-related adverse events continue to be a public health burden. Future studies with additional time points are necessary to confirm trends and determine whether recent risk mitigation efforts had a beneficial impact on acetaminophen-related adverse events.

Keywords: acetaminophen, overdose, emergency department, hospitalizations, pharmacoepidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Acetaminophen is widely used in the USA for reducing pain and fever.1,2 When used according to label directions, it has an established record of safety and efficacy. However, acetaminophen is a leading cause of drug toxicity that may lead to serious liver damage and death when the patient exceeds the maximum daily dose.3–6 The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has worked for several years to address the safety of acetaminophen. In 2002, an FDA Advisory Committee discussed acetaminophen-induced liver injury risk associated with unintentional overdoses and recommended a specific liver toxicity warning and distinctive labeling on over-the-counter (OTC) packages.7 In 2004, FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) launched a public education campaign for the safe use of acetaminophen-containing medicines and encouraged state boards of pharmacy to avoid use of abbreviations on pharmacy-generated prescription labels to improve patients’ ability to recognize their prescription medicines contain acetaminophen. In June 2009, FDA convened a meeting of the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committees to discuss acetaminophen-related adverse events and liver injury across a range of existing medical data and to propose additional regulatory measures.8

Following the 2009 Advisory Committee meeting, a multidisciplinary working group in CDER began developing recommendations to address acetaminophen-hepatotoxicity safety concerns. In 2011, CDER announced that manufacturers of prescription acetaminophen-combination products would be required to limit the amount of acetaminophen in products to 325mg per tablet, capsule, or other dosage and add proposed boxed warnings highlighting potential for severe liver injury. The change was to take approximately 3 years, with a January 2014 deadline for implementation of changes. The FDA’s Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology developed a surveillance plan to monitor the effectiveness of the risk mitigation efforts. The present study summarizes recent trends in rates of adverse events attributable to acetaminophen use (including hepatotoxicity and mortality) utilizing available resources that provide relevant data on poison center calls, emergency department (ED) visits, and hospitalizations.

METHODS

This study utilizes annual reports from the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) and data from two nationally representative surveillance databases: the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System – Cooperative Adverse Drug Events Surveillance (NEISS-CADES) project and the Nationwide In-patient Sample (NIS). The most current data were used at the time of analyses. Table 1 provides a summary of data elements available from these data sources.

Table 1.

Description of data elements available from data sources

| Characteristics | AAPCC* 2008–2012 | NEISS-CADES 2004–2012 | NIS 1998–2011 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Record level | Calls to poison control centers | Emergency department visits | Hospital discharges |

| Sampling frame | 57–61 centers each year | ~63 hospitals with EDs each year | ~1000 hospitals each year |

| Nationally projected estimates available | No | Yes | Yes |

| Acetaminophen-related events | Single exposures to analgesics, cold-and-cough preparations; single-ingredient or combination AP-containing products | Adverse drug events, including unintentional overdoses (ages 5+ years) or unsupervised ingestions (ages <5 years), adverse effects, allergic reactions, and therapeutic errors | ICD-9-CM (965.4): poisoning by aromatic analgesics |

| Age and gender available | Age: yes; gender: no | Yes | Yes |

| Intentionality classifications | Yes | Unintentional only† | Yes (E-codes) |

| Liver toxicity | No | No | Yes |

| Mortality | Yes | No | Yes (discharge status) |

ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification; NEISS-CADES, National Electronic Injury Surveillance System – Cooperative Adverse Drug Events Surveillance; NIS, Nationwide Inpatient Sample; AAPCC, American Association of Poison Control Centers; ED, emergency departments.

Based on published annual reports.

NEISS-CADES data do not include ED visits related to drug abuse or self-harm/suicide.

American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC)

Pre-tabulated summary tables from annual reports of the AAPCCs’ National Poison Data System were used to examine trends in acetaminophen-related exposures measured as calls to poison centers from 2008 to 2012. AAPCC is a network of approximately 60 poison centers nationwide that provide treatment advice by telephone.9 AAPCC annual reports summarize the total National Poison Data System exposure calls per generic code9–13 by age categories, reason for reported exposure, and medical outcome, but not by gender. We used single exposures to acetaminophen-containing products listed under analgesics and cold-and-cough preparations for the purposes of this study. Reasons for reported exposure include intentional exposures, unintentional exposures, adverse reactions, unknown, and other. Medical outcomes range from no medical outcome to major effect and death. The poison centers conduct follow-up calls to help ensure accuracy and completeness of medical outcomes.

National Electronic Injury Surveillance System – Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance (NEISS-CADES)

Data from NEISS-CADES provided national estimates of acetaminophen-related ED visits resulting from therapeutic drug use from 2004 to 2012. NEISS, a nationally representative active surveillance system, collects information on consumer product-related injuries reported in ED visits. The NEISS-CADES component (initiated in 2004) identifies ED visits due to ADEs. The approximately 60 participating hospitals in NEISS-CADES represent a stratified probability sample of US hospitals with a minimum of six beds and a 24-hour ED.14–16 Clinical descriptions and circumstances surrounding the ADE are coded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 9.1. Acetaminophen-containing products were identified based on verbatim names of implicated drugs and characterized by generic active components using a modified version of the Veterans Administration National Drug File. When nonspecific brand names were reported, cases of acetaminophen-related events were included only if all available formulations of the product contained acetaminophen. Cases include incident ED visits for a condition attributed to use of acetaminophen-containing product or an acetaminophen-specific effect (i.e., unintentional overdoses following therapeutic administration, adverse effects, allergic reactions, or other secondary effects). Cases resulting in death en route to or in the ED, or those involving abuse/recreational use or self-harm/suicide are not included. ED visits for ADEs involving acetaminophen-containing analgesics and acetaminophen-containing cold-and-cough products were included. Information on vital status was not available in NEISS-CADES.

Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS)

This study examined national estimates of acetaminophen-related hospitalizations from 1998 to 2011 using discharge data from the NIS, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. NIS is comprised of an annual 20% stratified sample of community hospitals resulting in approximately 8 million inpatient records per year from about 1000 nonfederal short-stay hospitals from states participating in Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Each event-level record includes patient characteristics as well as specific diagnoses (up to 15 from 1998 to 2003; 25 from 2004 to 2011) and up to five procedure codes according to the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). The external causes of injury and overdose codes (i.e., E-codes) of the ICD-9-CM provide information used to determine the intentionality of the poisoning. Any hospitalization with a primary or secondary diagnosis for poisoning by aromatic analgesics, not elsewhere classified (ICD-9-CM code 965.4), constituted a hospitalization for an acetaminophen-related poisoning. This definition uses a previously validated algorithm found to have a positive predictive value of 95% and a sensitivity of 90%.17 An intentional poisoning was defined as any hospital record with an external cause of injury listed as suicide or self-inflicted poisoning by analgesics, antipyretics, and antirheumatics (E950.0). Unintentional poisoning was any hospital record with an external cause of injury listed as accidental poisoning by aromatic analgesics, antipyretics, and antirheumatics (E850.4). Other intentionality included the remaining acetaminophen-related hospital records including assaults (homicide) and adverse effects of therapeutic use. Liver toxicity was defined as the presence of any of the following ICD-9-CM codes as a diagnosis in addition to the diagnoses of acetaminophen-related poisonings. Severe liver toxicity included hepatorenal syndrome (572.4), hepatic coma or hepatic encephalopathy (572.2), acute or subacute liver necrosis or acute hepatic failure (570), liver transplant (V42.7), or any encounter that listed liver transplant as a procedure code (50.5). Moderate liver toxicity included jaundice (782.4), coagulopathy (286.9), coagulation defect due to liver disease (286.7), or biliuria (791.4). Mild liver toxicity included transaminasemia (790.4) or hepatitis, non-infectious toxic (573.3). Unspecified liver toxicity was defined as any record not otherwise classified as severe, moderate, or mild and that listed unspecified liver disorder (573.9). In-hospital mortality was defined as an acetaminophen-related hospitalization with a discharge status of death.

Statistical Analysis

We examined annual rates according to their respective event setting (i.e., per 1000 poison center calls, per 1000 ED visits, and per 100 000 hospitalizations). For example, we used NIS to examine trends in hospital discharge rates from 1998 through 2011 by calculating hospital discharge rates (per 100 000 hospitalizations) in which the numerator was the nationally estimated number of acetaminophen-related hospitalizations and the denominator was the nationally estimated total hospitalizations for each of the 14 years.18 Test for trends in rates over time used weighted least squares regression and JOINPOINT software. However, cautious interpretation is needed when examining changes in trends pre-2009 and post-2009, given the potential limited number of years of data between joint points.

Next, to estimate population rates of poison center calls (2008 through 2012), ED visits (2004 through 2012), and hospitalizations (1998 through 2011), population data were obtained from the Census Bureau’s Population Estimates Program (www.census.gov). We determined annual rates per 1 million population by dividing the annual number of acetaminophen-related adverse events by the corresponding mid-year US census population to account for change in the US population over time.

Lastly, annual rates of acetaminophen-related adverse events were expressed per 1 million acetaminophen-containing drug units (i.e., OTC and prescription bottles/packages sold from manufacturers to retail and non-retail channels of distribution),19 thereby adjusting for change in sales over time where the majority of the acetaminophen sales data reflect OTC products. We utilized the total acetaminophen sales data to capture both prescription and OTC products because AAPCC annual reports and ICD-9 codes for NIS preclude distinguishing between prescription and OTC products in terms of acetaminophen-related poison center calls and hospitalizations.

The availability of additional data elements of NIS afforded the opportunity to describe acetaminophen-related poisonings that resulted in admission to a hospital by age group, gender, intentionality of poisoning, coexistent liver toxicity diagnosis, and in-hospital mortality. Sparse data for mortality precluded annual comparisons stratified by intentionality of poisonings or liver toxicity; therefore, we combined data across years to obtain overall (as opposed to annual) national estimates for these particular cross-tabulations.

Analyses used SAS® (version 9.3) statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). National estimates were obtained using standard methods for analyzing weighted data to account for sample weights and complex sampling design in calculation of percentages, means, and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for national estimates.20 In sensitivity analyses, the age–sex standardized rates were examined; results did not change markedly. All calculated p-values were two-sided.

RESULTS

From 2008 through 2012, US poison control centers received 558 159 single exposure calls involving acetaminophen-containing products, for an average of 111 632 per year (Table 2). Approximately two-thirds (67%) of these calls were for unintentional exposures; about half (49%) involved children 5 years of age or younger. The majority of acetaminophen-related exposures reported to poison control centers involved analgesics (88%, data not shown). One percent (n=6053) of the acetaminophen-related exposure calls involved life-threatening or debilitating events and 631 fatalities.

Table 2.

Summary of acetaminophen-related adverse events from data sources

| Characteristics | AAPCC* 2008–2012 | NEISS-CADES† 2004–2012 | NIS 1998–2011 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total acetaminophen-related adverse events | 558 159 | 8805 (unwtd) | 108 763 (unwtd) |

| 532 065 (wtd) | 534 739 (wtd) | ||

| Estimated average acetaminophen-related events per year | 111 632 | 59 118 | 38 196 |

| Among acetaminophen-related adverse events: | |||

| Est. % female | NA | 327 940 (62%) | 367 422 (69%) |

| Est. % unintentional | 373 817 (67%) | 219 228‡ (41%) | 84 279 (16%) |

| Est. % with liver toxicity | NA | NA | 54 238 (10%) |

| Est. % died | 631 (<1%) | NA | 6356 (1%) |

unwtd, unweighted and actual counts; wtd, weighted and nationally estimated counts; Est %, estimated percentages and corresponding standard errors, based on nationally estimated counts, if applicable (otherwise based on actual counts); NA, not applicable.

Based on published annual reports.

Estimates for adverse drug events involving acetaminophen-containing products (i.e., unintentional overdoses, allergic reactions, and medication errors). NEISS-CADES data do not include emergency department visits due to drug abuse and self-harm/suicide.

Unintentional overdoses.

From 2004 through 2012, there were an estimated 532 065 ED visits in the US for ADEs involving acetaminophen-containing products (Table 2), an estimated average of 59 118 annually. Women accounted for 62% (95%CI: 60–63%) of the estimated ED visits; those aged 18 years and over accounted for 75% (95% CI: 72–77%). A large percentage (41%, 95%CI: 38–45%) of annual visits were classified as unintentional overdoses (annual estimate of 24 358); the remaining comprised adverse effects, allergic reactions, and other secondary effects (e.g., falls and chocking). An estimated 9637 of annual ED visits involving acetaminophen-related unintentional overdoses were for unsupervised ingestions in children less than 5 years of age. Overall, 14% (95%CI: 12–16%) of ED visits for ADEs involving acetaminophen-containing products resulted in an acute-care hospitalization. Eighty percent (95%CI: 75–85%) of these ED visits requiring hospitalizations were for adults ages 18 years and older and 63% (95%CI: 57–69%) involved unintentional overdoses.

From 1998 through 2011, there were an estimated 534 739 hospitalizations associated with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code of acetaminophen-related poisonings, an estimated average of 38 196 per year (Table 2). The majority of these hospitalizations was for female patients (69%; 95%CI: 68–69%) and occurred primarily among adults (83%). Of note, 61% (95%CI: 60–62%) of the acetaminophen-related hospitalizations were among 18- to 44-year-olds; 67% (95%CI: 66–67%) and 59% (95%CI: 58–60%) were among the 18- to 44-year-olds for men and women, respectively. Two-thirds (67%, 95%CI: 66–68%) of estimated hospitalizations for acetaminophen-related poisonings were intentional, 16% (95%CI: 15–16%) unintentional, and 17% (95%CI: 16–18%) other/unspecified. Overall, an estimated 10% (95%CI: 10–11%, n=54238) of hospitalizations had a diagnosis for both acetaminophen-related poisoning and liver toxicity; 4.9%(95%CI: 4.7–5.1%) were intentional poisonings, 3.2% (95%CI: 3.0–3.4%) were accidental poisonings, and 2.0% (95%CI: 1.8–2.2%) were other/unspecified poisonings (Table 3). This pattern of slightly less accidental poisonings with coexistent liver toxicity remained when examining adults and children separately (data not shown). As shown in Table 3, less than 1% of the overall prevalence of acetaminophen-related hospitalizations included patients who were under the age of 18 years with a coexistent diagnosis of liver toxicity (adults comprised approximately 9.3%, 95%CI: 8.8–9.8%). The percentage of in-hospital mortality among those hospitalized for acetaminophen-related poisonings was approximately 1.2% (95%CI: 1.1–1.3%, n=6356). The proportion of hospitalizations for acetaminophen poisonings resulting in death during the same hospital stay was predominately comprised of adults (1.2%, 95%CI: 1.1–1.3%), women than men (0.8% (95%CI: 0.7–0.9%) vs. 0.4% (95%CI: 0.3–0.4%), respectively), and slightly lower for those with unintentional poisonings (0.3% (95%CI: 0.3–0.4%) vs. 0.4% (95%CI: 0.4–0.5%) for accidental and intentional poisonings, respectively).

Table 3.

Overall prevalence of acetaminophen-related hospitalizations by liver toxicity and mortality, NIS 1998–2011

| Acetaminophen-related hospitalizations n = 534 740 |

|

|---|---|

| Coexistent Liver Toxicity, % (95%CI) | 10.14% (9.64–10.65) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 6.65% (6.30–7.01) |

| Male | 3.49% (3.29–3.68) |

| Age group | |

| <18 years of age | 0.85% (0.76–0.94) |

| ≥18 years of age | 9.29% (8.81–9.78) |

| Intentionality | |

| Accidental | 3.23% (3.01–3.45) |

| Intentional | 4.90% (4.66–5.13) |

| Other/unspecified | 2.01% (1.83–2.20) |

| In-hospital mortality, % (95%CI) | |

| Gender | 1.19% (1.09–1.28) |

| Female | 0.81% (0.74–0.88) |

| Male | 0.38% (0.34–0.42) |

| Age group | |

| <18 years of age | — |

| ≥18 years of age | 1.17% (1.08–1.27) |

| Intentionality | |

| Accidental | 0.33% (0.28–0.37) |

| Intentional | 0.44% (0.39–0.49) |

| Other/unspecified | 0.42% (0.37–0.47) |

All percentages based on the total estimated number of acetaminophen-related hospitalizations (n = 534 740). National estimates with unweighted cell counts < 30 are not reported because of unstable estimates based on small numbers.

CI, confidence interval.

Trends over time by setting

The number of acetaminophen-exposed events reported to poison centers decreased from 121 900 in 2008 to 98 998 in 2012 (Appendix Table 1), a percent decrease of 19%. From year 2008, the number of estimated ED visits for acetaminophen-related ADEs increased from 54 451 to 68 901 in 2012 (27% increase), whereas hospitalizations decreased 13% from 47 826 to 41 840 in 2011 (2012 hospitalization data were unavailable). Figures 1 through 3 provide trends in the annual rates of poison center calls, ED visits, and hospitalizations expressed per setting-specific population, census population, and drug units. Appendix Figures 1 and 2 further provide the trends for poison center calls and inpatient hospitalizations by intentionality and by age groups, respectively. Overall, the rates of acetaminophen-related hospitalizations slowly increased from 1998 to 2009 (p-trend=0.001) by all three denominators, with the highest rate in 2008.

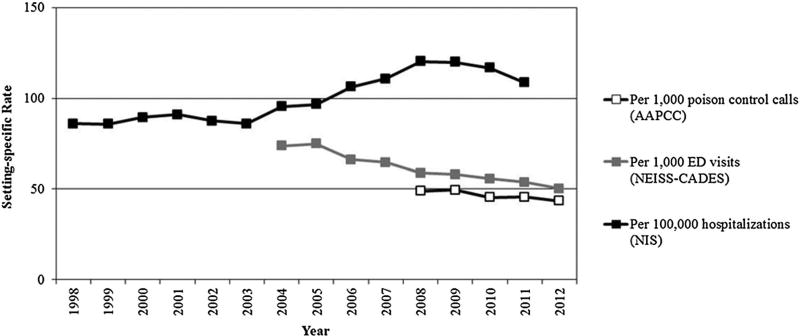

Figure 1.

Rates of acetaminophen-related events by event setting. AAPCC, American Association of Poison Control Centers; NEISS-CADES, National Electronic Injury Surveillance System – Cooperative Adverse Drug Events Surveillance; NIS, Nationwide Inpatient Sample

Rates per source population (poison center calls, ED visits, or hospitalizations)

Within each setting, there was a decrease in acetaminophen-related event rates after 2009 (per 1000 calls, 1000 ED visits for ADEs, and 100 000 hospitalizations) (Figure 1). The rate of poison center calls with acetaminophen-related exposures decreased from 49.5 per 1000 calls in 2009 to 43.5 per 1000 calls in 2012. Similarly, the rates of ED visits and inpatient hospitalizations for acetaminophen-related adverse events decreased (58.0 to 50.2 in 2012 and 119.8 to 108.6 in 2011 per 1000 ED visits for ADEs and 100 000 hospitalizations, respectively). Within the NIS, proportion of acetaminophen-related hospitalizations with an additional diagnosis for liver toxicity increased (from 6% in 1998 to 13% in 2011), and acetaminophen-related in-hospital mortality remained stable (approximately 1.2%) from 1998 to 2010; there was a slight increase in 2011 (1.5%). The Joinpoint Regression Program indicated a change in trend at years 2003 and 2009 during the 14-year study period for inpatient hospitalizations with a significant change in slope after 2009 (p-value =0.01). For NEISS-CADES and AAPCC, the annual percent change was significantly different from zero at α=0.05 (APC=−4.8, 95%CI: −5.6 to −4.0 and −3.1, 95%CI: −5.6 to −0.5, respectively).

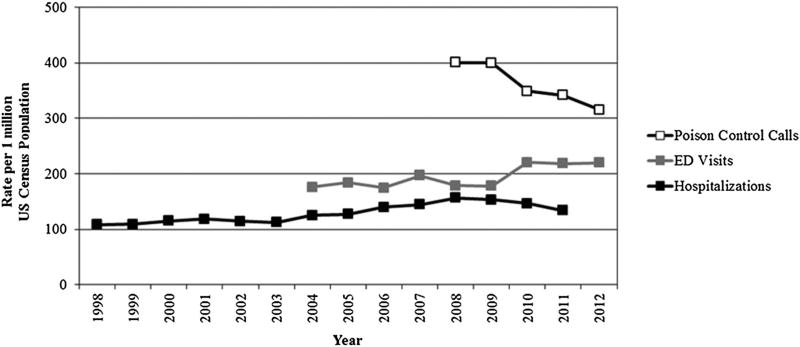

Rates per 1 million census population

The population rates per 1 million population decreased for poison control center calls and hospitalizations after 2009 and remained stable for ED visits (Figure 2). For calls to poison control centers, the rate of acetaminophen-exposed cases per 1 million population decreased during the study period, from 401 cases per million population in 2008 to 315 cases per million population in 2012. For ED visits, the rate of acetaminophen-related adverse events was similar for 2008 and 2009 (approximately 178 per 1 million population) but then increased in 2010 to 221 per 1 million population. The rate for ED visits was relatively consistent through 2012 (approximately 219 per 1 million population in both 2011 and 2012). The rates per 1 million population for acetaminophen-related hospitalizations decreased from 157 in 2008 to 134 in 2011. The Joinpoint results indicated a change in trend at years 2003 and 2008 during the 14-year study period for NIS. For NEISS-CADES, the annual percent change was significantly different from zero at α=0.05 (APC=3.1, 95%CI: 1.0–5.1). For AAPCC, the Joinpoint results indicate a change in trend at year 2009; the pre-2009 slope=−10.9, post-2009 slope=−25.5; however, because of insufficient number of data points prior to 2009, a significant change in slope pre-post 2009 could not be determined because the standard error prior to 2009 is unknown.

Figure 2.

Rates of acetaminophen-related events per 1 million census population. ED, emergency department

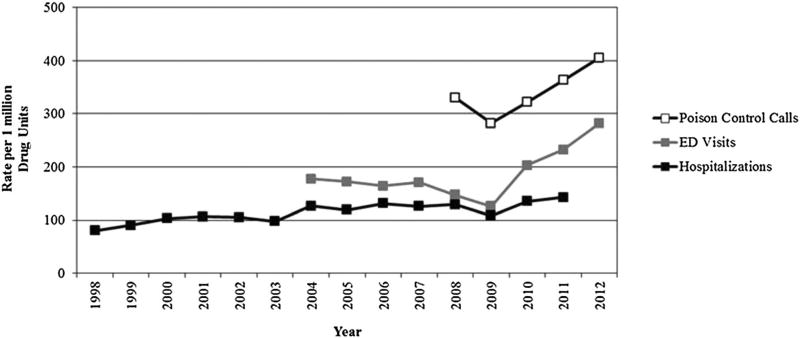

Rates per 1 million drug units sold/distributed

Figure 3 shows an increase in rates of acetaminophen-related events per 1 million drug units sold/distributed after 2009 for all three settings. The rate of poison center calls with acetaminophen-related exposures per 1 million drug units sold/distributed increased from 282.0 in 2009 to 405.3 in 2012. The rate of ED visits for acetaminophen-related adverse events per 1 million drug units sold/distributed increased from 125.7 in 2009 to 282.1 in 2012. Similarly, the rates per 1 million drug units sold/distributed for acetaminophen-related hospitalizations increased from 108.2 in 2009 to 142.9 in 2011. Overall sales of acetaminophen-containing products distributed from manufacturers increased 18% from 2008 to 2009 then decreased from 2010 to 2012. The proportion of prescription sales ranged from 11% to 33% during the entire study period. The Joinpoint results indicate a change in trend at year 2009 for NEISS-CADES (p-value=0.001) and AAPCC (pre-2009 slope=−48.7, post-2009 slope=41.1). However, because of insufficient number of data points prior to 2009 from AAPCC, a significant change in slope pre-post 2009 could not be determined because the standard error prior to 2009 is unknown. For NIS, the annual percent change was significantly different from zero at α=0.05 (APC=3.3, 95%CI: 1.9–4.7).

Figure 3.

Rates of acetaminophen-related events per 1 million drug units sold to retail and non-retail channels of distribution. Source for drug units: IMS Health, National Sales Perspectives™. Years 1998–2012. Data extracted April 2014. ED, emergency department

DISCUSSION

We observed a decrease in the pattern of acetaminophen-related event rates after 2009 within respective source populations (i.e., per 1000 poison center calls, 1000 ED visits, and 100 000 hospitalizations). The pattern across population rates per 1 million census population decreased among poison control centers and hospitals after 2009 and appeared stable for ED visits, whereas an increase in acetaminophen-related events (per 1 million drug units sold/distributed) was observed after 2009, when accounting for drug sales.

In addition, the proportion of acetaminophen-related hospitalizations with an additional diagnosis for liver toxicity continued to rise over the 14-year study period, doubling from 6% in 1998 to 13% in 2011. The observed increase is of potential concern given the large number of patients who use acetaminophen alone or in combination with other products in the US.1,2 A trend toward more liver injury diagnoses among acetaminophen-related inpatient hospitalizations suggests the importance of developing effective approaches to prevent acetaminophen poisoning among patients with potentially high-risk conditions for liver toxicity.

Consistent with previous studies21–25, we found that acetaminophen-related events remain a significant concern, albeit we observed an apparent decline in certain rates of acetaminophen poisonings in recent years, which support a previously reported decrease in ED visits attributable to acetaminophen overdose from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey.26 Our observation of a continued increase in coexistent liver toxicity is also consistent with previous studies.21 A closer examination showed hospitalizations for unintentional acetaminophen poisonings were no more likely to lead to liver toxicity than poisonings resulting from intentional self-inflicted poisonings; this pattern remained unchanged when separately examining adults. This finding is in contrast to the higher morbidity reported in an accidental overdose group from a case series of 93 patients hospitalized for acetaminophen poisoning at a single hospital in New York.27 However, it should be noted their reported morbidity (15%) was based on a small number of accidental cases (n = 13).

Potential limitations of the present study include variations in sampling scheme, calendar years spanned, and case/intentionality definitions, which precludes direct comparison of rates across studies. A potential challenge is the interpretation of trends using data based on voluntary reports (e.g., poison center calls), where it is not certain whether a decrease signifies a reduction in harm, a reduction in awareness of poison control centers, or less reliance on poison control centers by patients. However, data provided are informative in describing similar patterns of acetaminophen-related events by various settings over time. Although the denominator of a rate may be defined in a number of ways, ultimately the choice of which denominator to use depends on the question being asked.28 In the present study, the trends in rates that use drug sales as a denominator account for fluctuations in sales of acetaminophen-containing products over time and may better represent the population-at-risk for acetaminophen-related adverse events. A limitation being that the sales data are not a measure of direct patient use, it is unknown if patients actually consume the drug or if the drug is still on the pharmacy counters or in the medicine cabinets. Although sales of acetaminophen-containing products decreased after 2010 (partly explaining observed increases in sales-adjusted rates in recent years), the number of ED visits for acetaminophen-related ADEs has increased (with the highest number of estimated events in 2012). An additional limitation is that we cannot assume that all calls to poison centers or visits to EDs are due to acetaminophen toxicity when a combination product is implicated. For example, the increase in ED visits in the later years may be due to increased use of analgesic combination products and toxicity from non-acetaminophen components. We also cannot assume liver toxicity identified in the hospitalizations was the direct result of acetaminophen use; we only know that diagnosis codes for both acetaminophen overdose and liver toxicity were present during the same hospital stay. Furthermore, mortality in the NIS was determined from a hospital discharge status of death (thus only capturing in-hospital deaths), and information on cause of death was not available. Because of these limitations, liver toxicity and mortality associated with acetaminophen poisoning may be underestimated. Strengths of the present study include the large sample sizes across settings, calculation of national estimates for ED visits and hospitalizations, and ability to examine intentionality of acetaminophen-associated hospitalizations as well as coexistent liver toxicity and in-hospital mortality.

In conclusion, acetaminophen-related adverse events continue to be a public health burden, with an average of 112 000 poison center calls, 59 000 ED visits, and 38 000 hospitalizations annually in the US. Of concern, inpatient hospitalizations for liver toxicity with acetaminophen overdose continue to increase. From available data, it is not possible to determine adequately the potential beneficial impact of recent risk mitigation efforts on acetaminophen-related adverse events, particularly for the more recent 2011 FDA announcement to limit the dose of prescription products. Future studies that include additional time points are necessary to confirm recent trends and to quantify more fully the impact of recent risk mitigation efforts.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Acetaminophen-related adverse events continue to be a public health burden.

Events of coexistent liver toxicity and in-hospital mortality have not decreased.

Continued surveillance and additional years of data are needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Daniel Budnitz and Maribeth Lovegrove of the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for their help with the development of the definitions, analysis, and/or interpretation of this study.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The opinions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US FDA.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors state that no ethical approval was needed.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web site.

References

- 1.Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Rosenberg L, Anderson TE, Mitchell AA. Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the United States: the Slone survey. JAMA. 2002;287(3):337–344. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qato DM, Alexander GC, Conti RM, Johnson M, Schumm P, Lindau ST. Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(24):2867–2878. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chun LJ, Tong MJ, Busuttil RW, Hiatt JR. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and acute liver failure. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43(4):342–349. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31818a3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bower WA, Johns M, Margolis HS, Williams IT, Bell BP. Population-based surveillance for acute liver failure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(11):2459–2463. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, et al. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2005;42(6):1364–1372. doi: 10.1002/hep.20948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheen CL, Dillon JF, Bateman DN, Simpson KJ, Macdonald TM. Paracetamol toxicity: epidemiology, prevention and costs to the health-care system. QJM. 2002;95(9):609–619. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/95.9.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Joint meeting of the Non-prescription Drug Advisory Committee with the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee, Anesthetic and Life Support Drugs Advisory Committee, Arthritis Advisory Committee, and Gastrointestinal Drugs Advisory Committee: meeting announcement. [accessed 12 March 2014];2002 Sep 19–20; www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/cder02.htm#NonprescriptionDrugs.

- 8.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Joint meeting of the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee with the Anesthetic and Life Support Drugs Advisory Committee and the Non-prescription Drug Advisory Committee. [accessed 12 March 2014];2009 Jun 29–30; www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/Calendar/ucm143083.htm.

- 9.Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Bailey JE, Ford M. 2012 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 30th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2013;51(10):949–1229. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.863906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Green JL, Rumack BH, Giffin SL. 2008 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 26th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009;47(10):911–1084. doi: 10.3109/15563650903438566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Green JL, Rumack BH, Giffin SL. 2009 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 27th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2010;48(10):979–1178. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2010.543906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Green JL, Rumack BH, Dart RC. 2010 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 28th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011;49(10):910–941. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.635149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Rumack BH, Dart RC. 2011 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 29th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2012;50(10):911–1164. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2012.746424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jhung MA, Budnitz DS, Mendelsohn AB, Weidenbach KN, Nelson TD, Pollock DA. Evaluation and overview of the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance Project (NEISS-CADES) Med Care. 2007;45(10 Supl 2):S96–102. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318041f737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Budnitz DS, Pollock DA, Weidenbach KN, Mendelsohn AB, Schroeder TJ, Annest JL. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA. 2006;296(15):1858–1866. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroeder T, Ault K. National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) Sample Design and Implementation From 1997 to Present. Consumer Product Safety Commission; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myers RP, Leung Y, Shaheen AA, Li B. Validation of ICD-9-CM/ICD-10 coding algorithms for the identification of patients with acetaminophen overdose and hepatotoxicity using administrative data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:159. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houchens R, Elixhauser A. Using the HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample to estimate trends. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.IMS Health. IMS National Sales Perspectives™ Retail and Non-Retail Sample Coverage of the Universe. [accessed April 2014];1998–2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houchens R, Elixhauser A. Calculating Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) variances, 2001. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bond GR, Ho M, Woodward RW. Trends in hepatic injury associated with unintentional overdose of paracetamol (acetaminophen) in products with and without opioid: an analysis using the National Poison Data System of the American Association of Poison Control Centers, 2000–7. Drug Saf. 2012;35(2):149–157. doi: 10.2165/11595890-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manthripragada AD, Zhou EH, Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Willy ME. Characterization of acetaminophen overdose-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(8):819–826. doi: 10.1002/pds.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Crosby AE. Emergency department visits for over-doses of acetaminophen-containing products. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(6):585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox S, Kuo C, Jamieson DJ, et al. Poisoning hospitalisations among reproductive-aged women in the USA, 1998–2006. Inj Prev. 2011;17(5):332–337. doi: 10.1136/ip.2010.029793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nourjah P, Ahmad SR, Karwoski C, Willy M. Estimates of acetaminophen (Paracetomal)-associated overdoses in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(6):398–405. doi: 10.1002/pds.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li C, Martin BC. Trends in emergency department visits attributable to acetaminophen overdoses in the United States: 1993–2007. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(8):810–818. doi: 10.1002/pds.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gyamlani GG, Parikh CR. Acetaminophen toxicity: suicidal vs. accidental. Crit Care. 2002;6(2):155–159. doi: 10.1186/cc1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riegelman RK. Studying a Study & Testing a Test: How to Read the Medical Evidence. 5. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.