Abstract

Objectives

Pre-antiretroviral therapy (ART) inflammation and coagulation activation predict clinical outcomes in HIV-positive individuals. We assessed whether pre-ART inflammatory marker levels predicted the CD4 count response to ART.

Methods

Analyses were based on data from the Strategic Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) trial, an international trial evaluating continuous vs. interrupted ART, and the Flexible Initial Retrovirus Suppressive Therapies (FIRST) trial, evaluating three first-line ART regimens with at least two drug classes. For this analysis, participants had to be ART-naïve or off ART at randomization and (re)starting ART and have C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and D-dimer measured pre-ART. Using random effects linear models, we assessed the association between each of the biomarker levels, categorized as quartiles, and change in CD4 count from ART initiation to 24 months post-ART. Analyses adjusted for CD4 count at ART initiation (baseline), study arm, follow-up time and other known confounders.

Results

Overall, 1084 individuals [659 from SMART (26% ART naïve) and 425 from FIRST] met the eligibility criteria, providing 8264 CD4 count measurements. Seventy-five per cent of individuals were male with the mean age of 42 years. The median (interquartile range) baseline CD4 counts were 416 (350–530) and 100 (22–300) cells/µL in SMART and FIRST, respectively. All of the biomarkers were inversely associated with baseline CD4 count in FIRST but not in SMART. In adjusted models, there was no clear relationship between changing biomarker levels and mean change in CD4 count post-ART (P for trend: CRP, P = 0.97; IL-6, P = 0.25; and D-dimer, P = 0.29).

Conclusions

Pre-ART inflammation and coagulation activation do not predict CD4 count response to ART and appear to influence the risk of clinical outcomes through other mechanisms than blunting long-term CD4 count gain.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, CD4 count, coagulation, C-reactive protein, D-dimer, highly active antiretroviral therapy, HIV, immunological response, inflammation, interleukin-6

Introduction

Long-term immunological outcomes in HIV-positive individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) are one of the most important determinants of the risk of AIDS-related events and serious non-AIDS-related (SNA) events in treated HIV-positive individuals [1,2]. By far, CD4 count at ART initiation is understood to be the key factor in determining CD4 count trajectory post-ART. Pre-ART inflammation and coagulation activation also play an important role in determining the risk of long-term clinical outcomes [3–8]. However, it is unclear whether pre-ART inflammation adversely impacts long-term gain in CD4 T-cell count (henceforth CD4 count) post-ART, independent of CD4 count at ART initiation.

In a recent case–control study from the AIDS clinical trials group longitudinal linked randomized trials (ALLRT) cohort [6], both pre-ART and post-ART markers of inflammation and coagulation were associated with SNA outcomes. While some postulate that this relationship is, in part, explained by subsequent immunodeficiency (possibly induced by immune activation and exhaustion), others suggest that these processes impact outcomes somewhat independent of CD4 count [3,6,9]. The authors of the ALLRT study postulated that there may be at least two pathways to serious clinical outcomes: long-term inflammation and long-term immunodeficiency, with the link between the two as yet unclear [6]. These studies did not investigate the link between pre-ART inflammation and CD4 count trajectory post-ART, especially in those starting ART at high CD4 counts (> 200–300 cells/µL). Investigating this relationship could not only provide a mechanistic insight into the process of how inflammation relates to clinical outcomes, but also provide a predictive tool for long-term CD4 count gain, beyond pre-ART CD4 count.

Using data from the Strategic Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) and Flexible Initial Retrovirus Suppressive Therapies (FIRST) trials, we sought to investigate whether pre-ART inflammation and coagulation activation predict CD4 count response to ART in HIV-positive patients (re)initiating ART at a wide range of baseline CD4 counts.

Methods

Study population

The SMART trial was a large multi-country trial (the findings of which have been published previously) [10], comparing the strategy of continuous ART [viral suppression (VS) arm] vs. CD4 count-guided interruption of ART [drug conservation (DC)]. Follow-up was scheduled at randomization, months 1 and 2, and then every 2 months for the first year and then 4-monthly thereafter. The FIRST trial (the results of which have also been published elsewhere [11]) compared three first-line ART strategies using two or three classes of antiretrovirals, such that all patients received at least two classes of antiretrovirals. Follow-up was scheduled at randomization, months 1 and 4, and then every 4 months. CD4 count and viral load were measured at all follow-up visits.

We conducted a retrospective exploratory analysis on the subset of SMART and FIRST participants who, at randomization, were ART naïve (all FIRST participants and a subset of SMART participants [12]) or off ART (a subset of SMART participants [12]) and had had biomarkers measured. In SMART, the majority (> 75%) of participants have had their baseline biomarkers measured in stored samples after they provided appropriate consent. In FIRST, biomarkers have been measured only for selected participants who consented and were included in previous studies (Boulware et al. [4], a case−control study focussed on AIDS and mortality outcomes, and Andrade et al. [13], a nested cohort study focussed on flare in hepatitis virus-coinfected individuals).

Outcome

The outcome was the absolute change in CD4 count during the follow-up from (re)start of ART (visit 0) to 24 months post-ART. The CD4 count change was calculated by subtracting CD4 count at each visit from that at ART initiation.

Covariates

The main covariables of interest were markers of inflammation, including highly sensitive C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) and the coagulation activation marker D-dimer, all measured at randomization pre-ART. These markers were chosen as they have been consistently shown to be associated with adverse clinical outcomes [6,14,15]. The details regarding measurement of these markers in each trial have been published previously [4,7]. Of note, in each study, markers were measured at two different laboratories, using different assays, especially for D-dimer and CRP (also see sensitivity analyses).

Markers were categorized as quartiles. We also generated an ‘inflammation score’ by ranking each patient according to the level of each of the markers. Ranks for each patient were then added up to generate the score. Thus, a higher score reflects high inflammation/coagulation activation. This score was also analysed as quartiles.

Other baseline (defined as ART initiation) variables of interest included: age, CD4 count (categorized as < 50, 50–200, 201–350, 351–500 and > 500 cells/µL), sex, race (white, black and other), mode of transmission [injecting drug user (IDU) and other], hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) status [HBV surface (HBs) antigen and HCV antibody positive or negative, respectively], body mass index (BMI; defined as weight (kg)/height (m2) and categorized as < 18.5, 18.5–25, >25–30 and > 30), history and duration of any prior ART (if any), duration or date of HIV infection (if known) and viral load (log10 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL).

Statistical considerations

The follow-up commenced at the (re)initiation of ART. ART status was as per intention to treat, i.e. once ART was started, patients were assumed to be on ART for the duration of the follow-up (except for the SMART DC arm). The SMART DC arm was only analysed for participants’ first episode of ART (i.e. they were censored once they stopped ART) because they went through a structured interruption in their ART. We used all of the available CD4 counts measured at months 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20 and 24 (visits at months 2, 6 and 10 were missing in FIRST participants). Initially, we plotted mean change in CD4 count at each visit by the quartiles of each baseline biomarker. We then fitted random effects linear models (which account for repeat measurements of CD4 count) to model change in CD4 count. Time was modelled as visits (categorical variable with a category for each visit). A few DC arm participants who started ART later in the follow-up had a visit structure that did not conform to the above schedule. For the analysis, their visit number was aligned to the nearest possible number from the visit structure of months 0 (ART initiation), 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20 and 24 (for example, their visit ‘x’ in the trial when they commenced ART was visit ‘0’ for the analysis). Models were adjusted for trial treatment arm (VS/DC or the three arms of the FIRST trial) and for variables mentioned above.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted by (1) including only SMART participants in the analysis, as laboratorial methods and selection criteria differed in the two studies; (2) including in the analysis only FIRST participants who were included in Andrade et al. [13] (as they were not selected on case−control status) and the SMART VS arm (as the DC arm had a greater time gap between biomarker measurement and start of ART); and (3) analysing the following alternative outcomes: percentage change in absolute CD4 count, change in CD4 percentage and change in CD4:CD8 ratio, which were only available in the SMART cohort.

Results

Overall, 659 SMART (26% ART naïve) and 425 FIRST study participants met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis. The patient characteristics at ART initiation in each trial are provided in Table S1. Overall (n = 1084 with 8264 measurements), about 75% of participants were male with the mean age of 42 years, 37% and 47% were white and black, respectively, 22% reported IDU, and 9.6% and 32.8%, respectively, were known to be HBV and HCV positive. The medians [interquartile ranges (IQR)] of key variables at ART (re)initiation were as follows: CD4 count, 360 (265–473) cells/µL; D-dimer, 0.43 (0.25–0.81) µg/mL; CRP, 1.69 (0.69–4.12) µg/mL, and IL-6, 2.59 (1.63–4.45) pg/mL. The median (IQR) CD4 counts in SMART and FIRST were 416 (350–530) and 100 (22–300) cells/µL, respectively. Overall, hepatitis B and C prevalence and values of all the biomarkers tended to be higher in FIRST participants.

Patient characteristics of the SMART subset were broadly similar to those of the entire SMART study population [10]. FIRST patients selected for this study (vs. the entire FIRST study) had substantially lower CD4 counts (100 cells/µL in this study vs. 162 cells/µL in the main study) and a higher prevalence of hepatitis C (54% vs. 20%, respectively) and B (18% vs. 6%, respectively) [11]. This was most likely due to the fact that the FIRST participants who contributed to this analysis were selected as the part of previous case-control studies [4,13]. (See 2nd paragraph under ‘Study population’ under ‘Methods’).

All of the markers showed an inverse correlation with the baseline CD4 count, largely driven by a strong correlation in the FIRST cohort (P < 0.05 for the interaction between baseline CD4 count and study). In FIRST, the coefficient for each marker (95% confidence interval) per 100 cells/µL increment in baseline CD4 count was: D-dimer, −0.11 (−0.16, −0.06); IL-6, −1.11 (−2.03, −0.18); and CRP, −1.30 (−2.24, −0.37).

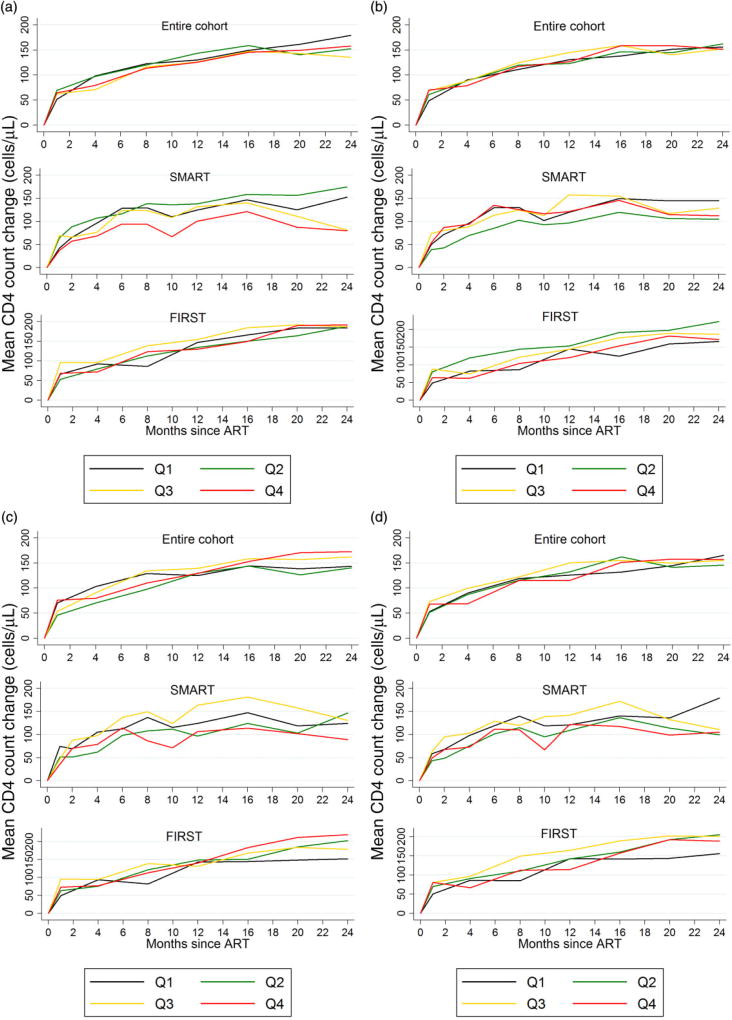

Figure 1 shows the mean CD4 count change by the quartile of each biomarker, overall and separately for each trial. There was no suggestion of any clear trend between changing quartiles of any of the biomarkers at baseline and the trajectory of CD4 count change.

Fig. 1.

Change in CD4 count since (re)initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) by pre-ART quartiles of biomarkers. (a) Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and CD4 count change. (b) C-reactive protein (CRP) and CD4 count change. (c) D-dimer and CD4 count change. (d) Inflammation rank score (see main text for details) and CD4 count change. Q, quartile (Q1, first quartile etc.); SMART, Strategic Management of Antiretroviral Therapy trial; FIRST, Flexible Initial Retrovirus Suppressive Therapies trial.

Table 1 provides the adjusted mean difference in CD4 count change across all visits for quartiles of each biomarker from random effect models. These models were adjusted for the baseline CD4 count category, visit, and all of the variables mentioned in the ‘Methods’ section. After accounting for key variables, there did not appear to be any clear relationship between changing biomarker level and mean change in CD4 count (P > 0.05 for trend for all markers).

Table 1.

Adjusted* differences in mean CD4 count change post-antiretroviral therapy (ART) by quartiles of inflammation and coagulation markers and baseline CD4 count

| Difference in mean CD4 count change relative to reference (95% CI), P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Covariate | IL-6 | CRP | D-dimer | Inflammation rank score |

| Quartiles of the biomarker | ||||

| 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 2 | −2.71 (−21.94 to 16.52), 0.78 | 1.01 (−18.30 to 20.31), 0.92 | −20.35 (−39.86 to −0.84), 0.04 | 0.19 (−19.40 to 19.79), 0.985 |

| 3 | −5.10 (−25.11 to 14.91), 0.62 | 3.72 (−16.16 to 23.60), 0.71 | −7.47 (−27.39 to 12.46), 0.46 | 7.35 (−12.79 to 27.49), 0.475 |

| 4 | −11.93 (−32.44 to 8.58), 0.25 | −0.96 (−21.03 to 19.11), 0.93 | −16.32 (−37.15 to 4.51), 0.13 | −10.94 (−31.82 to 9.94), 0.304 |

| P for trend | 0.25 | 0.97 | 0.29 | 0.44 |

| Baseline CD4 count | ||||

| <50 cells/µL | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 50–200 cells/µL | 6.70 (−19.41 to 32.80), 0.62 | 6.74 (−19.40 to 32.88), 0.61 | 5.75 (−20.35 to 31.85), 0.67 | 5.77 (−20.39 to 31.92), 0.67 |

| 200–350 cells/µL | 9.72 (−18.58 to 38.02), 0.50 | 11.15 (−17.06 to 39.37), 0.44 | 9.26 (−19.05 to 37.58), 0.52 | 10.17 (−18.08 to 38.42), 0.48 |

| 350–500 cells/µL | −12.45 (−41.77 to 16.87), 0.41 | −10.74 (−39.95 to 18.48), 0.47 | −11.46 (−40.76 to 17.84), 0.44 | −11.41 (−40.66 to 17.85), 0.44 |

| >500 cells/µL | −39.60 (−71.32 to −7.87), 0.01 | −38.75 (−70.51 to −7.00), 0.02 | −39.34 (−71.08 to −7.59), 0.01 | −39.59 (−71.28 to −7.90), 0.01 |

Each column represents an individual model for each biomarker, adjusted for baseline CD4 count, visit (categorical variable), race, age, gender, body mass index category, time since HIV diagnosis, hepatitis B and C status, viral load, duration of prior ART (if any) and treatment arm. In addition to baseline CD4 count and visit, other significant variables in all of these models were race, viral load, and treatment group, and hepatitis C was borderline significant. See main text for the definition of inflammation rank score. CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6.

Results were robust to all of the sensitivity analyses. Restricting the analysis to FIRST participants in the Andrade et al. [13] study and the SMART VS arm did not impact the results (P > 0.05 for trend for all markers). Finally, biomarker levels were not significantly associated with percentage change in CD4 count, change in CD4 percentage and CD4:CD8 ratio (n = 2473 available measurements) (P > 0.05 for each biomarker and outcome combination).

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the impact of markers of pre-ART inflammation (CRP and IL-6) and coagulation activation (D-dimer) on the change in CD4 count in response to (re)initiation of ART in those commencing ART at a wide range of CD4 counts. We found that the pre-ART level of inflammation and coagulation did not predict the change in CD4 count over up to 2 years post-ART, after accounting for CD4 count at ART commencement, time on ART and other key factors. CD4 count at ART initiation was the strongest predictor of the CD4 count response to ART.

Pre-ART levels of these markers seem to play an important role in the development of AIDS and SNA outcomes [3,5,6]. Some authors postulate the existence of a pre-ART inflammation ‘set-point’ which independently impacts future health [6]. However, it has been unclear whether these markers impact long-term CD4 count trajectory, thereby resulting in adverse outcomes. Also, whether the strategy of suppressing pre-ART inflammation will boost long-term CD4 count gain post-ART is unclear. Conversely, low CD4 count could also directly/indirectly affect the inflammation process. Our analysis helps to disentangle this complex relationship and lends further support to the hypothesis that pre-ART inflammation and coagulation activation do not blunt long-term CD4 count gain and might be associated with clinical outcomes through alternative mechanisms. These findings imply that the potential clinical benefit of suppressing pre-ART inflammation may not be apparent in the CD4 count trajectory over time. Of note, it is possible that the residual inflammation while on ART could be associated with ongoing CD4 count changes; this was not evaluated in the current study.

These observations have a few implications. As inflammation appears to be a somewhat independent process impacting clinical outcomes, the provision of ART (which is known to reduce inflammation) might provide the greatest benefit to people with higher pre-ART inflammation/coagulation activation independent of their CD4 count. This idea of providing ART to those with high inflammation might help to select candidates likely to benefit from ART, when the benefit by CD4 count criteria is unclear (for example, in those with CD4 counts > 500 cells/µL where the clinical benefit of ART is unclear, and is a matter of current investigation in the START trial [16]).

The strengths of our study include the large sample size and the heterogeneous group of participants with near complete follow-up at structured visits. This ensured that our study had enough power to at least detect a clinically meaningful difference, and minimized bias from missing data. The study has a few limitations. First, it was conducted on a selected sample from a large study, which, especially in case of the FIRST trial, was different to the parent study. Also, biomarkers were measured at different laboratories in each trial, possibly resulting in measurement error or inconsistency in values between the two trials. However, stratifying by trial and various sensitivity analyses restricted to subcohorts did not impact our results.

In conclusion, we found that pre-ART inflammation/coagulation activation does not predict the CD4 count trajectory post-ART. These findings suggest that inflammation is probably an independent pathological process associated with the development of serious clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health [grant numbers: U01AI042170 and U01AI46362 (SMART); U01AI042170, U01AI046362 and U01AI068641 for the FIRST study (CPCRA 058)] and INSIGHT, as well as through the Intramural Research Program of NIAID. In addition, this project has been supported in part by federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. DRB is supported by NIAID grant K23AI073192-02, and JVB by grant K12RR023247-05. We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the SMART and FIRST participants, the SMART study team (see El-Sadr et al. [10] for a list of investigators), the FIRST study team (see Boulware et al. [4] and MacArthur et al. [11] for lists of investigators), and the INSIGHT Executive Committee.

Footnotes

Results from this paper were presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 23–26 February 2015, Seattle, WA, USA.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no other relevant conflicts of interest.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site: Table S1 Patient Characteristics at ART initiation overall and by trial.

References

- 1.Achhra AC, Petoumenos K, Law MG. Relationship between CD4 cell count and serious long-term complications among HIV-positive individuals. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9:63–71. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Achhra A, Amin J, Law M, et al. Immunodeficiency and the risk of serious clinical endpoints in a well studied cohort of treated HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2010;24:1877–1886. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833b1b26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalayjian Robert C, Machekano Rhoderick N, Rizk N, et al. Pretreatment levels of soluble cellular receptors and interleukin-6 are associated with HIV disease progression in subjects treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1796–1805. doi: 10.1086/652750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boulware D, Hullsiek K, Puronen C, et al. Higher levels of CRP, D-dimer, IL-6, and hyaluronic acid before initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) are associated with increased risk of AIDS or death. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1637–1646. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McComsey GA, Kitch D, Sax PE, et al. Associations of inflammatory markers with AIDS and non-AIDS clinical events after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: AIDS clinical trials group A5224s, a substudy of ACTG A5202. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:167–174. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000437171.00504.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tenorio AR, Zheng Y, Bosch RJ, et al. Soluble markers of inflammation and coagulation, but not T-cell activation, are predictors of non-AIDS-defining morbid events during suppressive antiretroviral treatment. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:1248–1259. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuhaus J, Jacobs J, David R, et al. Markers of inflammation, coagulation, and renal function are elevated in adults with HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1788–1795. doi: 10.1086/652749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ledwaba L, Tavel JA, Khabo P, et al. Pre-ART levels of inflammation and coagulation markers are strong predictors of death in a South African cohort with advanced HIV disease. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e24243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamlyn E, Fidler S, Stohr W, et al. Interleukin-6 and D-dimer levels at seroconversion as predictors of HIV-1 disease progression. AIDS. 2014;28:869–874. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2283–2296. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacArthur RD, Novak RM, Peng G, et al. A comparison of three highly active antiretroviral treatment strategies consisting of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, or both in the presence of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors as initial therapy (CPCRA 058 FIRST Study): a long-term randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;368:2125–2135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69861-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy Study G. Emery S, Neuhaus JA, et al. Major clinical outcomes in antiretroviral therapy (ART)-naive participants and in those not receiving ART at baseline in the SMART study. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1133–1144. doi: 10.1086/586713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrade BB, Hullsiek KH, Boulware DR, et al. Biomarkers of inflammation and coagulation are associated with mortality and hepatitis flares in persons coinfected with HIV and hepatitis viruses. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1379–1388. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Achhra AC, Amin J, Sabin C, et al. Reclassification of risk of death with the knowledge of D-dimer in a cohort of treated HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2012;26:1707–1717. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328355d659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W, et al. Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundgren J, Babiker A, Gordin F, Borges A, Neaton J. When to start antiretroviral therapy: the need for an evidence base during early HIV infection. BMC Med. 2013;11:148. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.