Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate (HR), rating of perceived exertion (RPE) and perceived enjoyment responses to a repeated-sprint training session (RST) compared to a small-sided soccer game session (SSG) in untrained adolescents. Twelve healthy post-pubertal adolescent males (age 15.8±0.6 years, body mass 59.1±3.7 kg, height 1.7±0.1m) performed RST and SSG sessions in a randomized and counterbalanced order. Blood pressure and HR were measured at rest and at 10, 20 and 30 minutes after interventions, and RPE and enjoyment were assessed. RST and SSG elicited similar exercise HR (74.0% vs. 73.7% of HR peak during RST and SSG respectively, P>0.05). There was no significant change in SBP or DBP after the 2 interventions (all P>0.05, ES<0.5) with a trend to a decrease in SBP after SSG at 30 min after intervention (moderate effect, ES=0.6). Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed a significant and large correlation between baseline BP values and magnitude of decline after both RST and SSG. Heart rate during recovery was higher compared with baseline at all times after both sessions (all P<0.05), with HR values significantly lower after SSG versus RST at 30 min after interventions (82.3±3.2 versus 92.4±3.2 beats/min, respectively, P=0.04). RPE was significantly lower (P=0.02, ES=1.1) after SSG than after RST, without significant differences in enjoyment. In conclusion, repeated sprint and small-sided games elicited similar exercise intensity without a significant difference in perceived enjoyment. Post-exercise hypotension after the two forms of training may depend on resting BP of subjects.

Keywords: Physical activity, Health, Post-exercise hypotension, Football

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases represent the primary cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide [1,2]. Moreover, it has been shown that cardiovascular disease and especially a high level of BP are becoming more premature among young and paediatric populations [3,4]. Moreover, physical inactivity and lifestyle-related diseases during childhood and adolescence are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and greatly contribute to the burden of disease, death, and disability during adulthood [5–7].

Despite the potential benefits of exercise, some estimates suggest that many adolescents do not achieve recommended levels of physical activity [8]. This is probably due to the lack of enjoyment and motivation frequently related to classical intervention modes such as continuous exercise, therefore leading to low adherence [9–11]. It is well acknowledged that enjoyment is one of the most influential factors to increase participation in physical activity, particularly in paediatric populations [12]. Thus, it is important to investigate training strategies capable of increasing physical activity levels among adolescents, in order to effectively reduce cardiovascular risk and improve their health.

Recently, sprint interval training or repeated sprint (RST) and small-sided soccer games (SSG) have emerged as feasible and efficacious strategies for addressing the lack of motivation for participation in physical activity. Firstly, RST can induce high neuromuscular and metabolic stress, with significant involvement of the aerobic system [13]. Furthermore, it represents an attractive training strategy compared with continuous aerobic running or cycling exercises [14,15]. Secondly, a growing amount of research has highlighted the health benefits from recreational SSG training in sedentary healthy and unhealthy individuals [16–18]. In comparison with continuous exercises, higher exercise intensities might be achieved during SSG with a lower rate of perceived effort [19], which supports its application as a strategy to improve health and increase physical activity levels in sedentary individuals.

Despite these promising applications, physiological and enjoyment responses to SSG and RST have not been investigated in untrained adolescents. Given the increasing interest in health benefits related to repeated sprint running exercise and recreational soccer training, the present study aimed to compare the acute effects of RST and SSG on heart rate and post-exercise blood pressure in untrained adolescents. Additionally, the degree of physical activity enjoyment and RPE were assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was designed to compare the acute effects of an RST training session and SSG on HR during exercise, post-exercise HR recovery, SBP, DBP, RPE, and enjoyment in healthy untrained adolescent boys. Using a randomized counterbalanced design, after baseline testing and familiarization sessions, 2 experimental sessions (RST and SSG) were conducted with 48-72 h intervals in between. The 2 familiarization sessions included measurement of resting HR and BP and performing the RST and SSG in each session. The experimental sessions included the measurements of HR and BP that were performed before (after 15 min of seated rest) and every 10 minutes for 30 minutes after each session. RPE and physical activity enjoyment were also evaluated 5 min after each intervention.

Subjects

Twelve untrained healthy adolescent boys (age 15.8±0.6 years, body mass 59.1±3.7 kg, height 1.7±0.1m, and BMI 20.0±1.6) were recruited for the study. During the study, participants were involved only in regular physical education programmes. All participants were fully informed of risks and discomforts associated with the experimental procedures, and their parents signed informed consent providing authorization to participate in the study. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee in conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki for human research.

Procedure

Participants were randomly allocated to two groups. After baseline assessment of body composition and HR peak, participants performed either a small-sided soccer game session (SSG) or repeated sprint running session (RST) in a counterbalanced design. Each session started with a brief dynamic warm-up (7 min: jogging + active dynamic stretching) followed by the exercise session (20 min). All sessions and measurements were performed at the same time of day (i.e., between 1:00 and 3:00 pm) at temperature ranging from 18 to 23°C.

Anthropometric and maturity assessment

Body mass and height were measured in standard conditions with minimal clothes. Four skinfolds (biceps, triceps, suprailiac, subscapular) were obtained by an experienced evaluator using a Harpenden caliper (Lange, Cambridge, MA, USA). Age at peak height velocity (PHV) was used as an indicator of maturity, representing the time of growth spurt during adolescence [20]. The PHV was calculated using sex-specific equations based on anthropometric measures (body mass, height, leg length, sitting height) [20].

Heart rate and blood pressure assessment

Measurement of HR peak was performed by means of the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1 [21]. The test consisted of a repeated 20-m run back and forth between 2 markers/lines, with progressive velocity adjusted using an audio player specific band. Participants were allowed to recover for 10 s in between each 40-m bout. The test was completed when the participant failed twice to maintain the running pace or reached voluntary exhaustion. The HR was measured by heart rate monitors (Polar S-810, Polar-Electro, Kempele, Finland, recording one value each 5 s), and the maximal HR achieved during the test was recorded as HR peak. A recent study by Póvoas et al. [22] demonstrated that Yo-Yo IRT test performance and HR peak are correlated and reliable in 9-16 year-old footballers and recreationally active boys.

Twenty-four hours before the experimental sessions, all subjects were instructed to avoid any strenuous physical activity or caffeine intake. Heart rate data were continuously collected at baseline, during the training session and 30 min after each session. Resting HR was evaluated during 10-min rest in a sitting position. Procedures for BP measurement followed the American Heart Association guidelines [23]. Resting SBP and DBP were measured in duplicate, using an automatic upper-arm blood pressure monitor (PK-HEM-7200; OMRON M3, Japan), with the subjects seated in a comfortable position in a quiet room for a minimum of 15 min. Post-exercise BP was measured in duplicate each time point at 10 min, 20 min and 30 min after interventions. An automated BP measurement system was used in order to prevent investigator bias in the reading of blood pressure between trials.

Perceived effort and enjoyment assessment

Within the first 10 minutes of post-exercise recovery, the RPE was assessed by means of Borg’s CR-10 point scale [24]. Enjoyment level after each intervention was also evaluated using a modified and validated Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) [25]. This questionnaire includes 16 items concerning different aspects of enjoyment, which are rated according to a 5-point Likert-type scale. The sum of scores was used for analysis.

Small-sided soccer game session

During the SSG, participants performed 3 repetitions of 3 min of an adapted 3 vs. 3 players’ soccer game, interspersed with 2 min of passive rest in between (approximately 12 min total time). In order to progressively increase the exercise intensity, the pitch size was increased from 20 m (length) x 12 m (width), to 25 m x 15 m, and to 30 m x 18 m, in the first, second, and third repetition, respectively [26]. Participants were asked to maintain high exercise intensity during each training session and to avoid intensive or forceful contacts and movements to avoid injuries.

Repeated sprint running session

Participants performed two sets of 6 repetitions of 30-m sprint with a 180° change of direction (15m +15m). Twenty seconds of recovery were allowed between sprints and 4 min between the two sets [27]. The session lasted approximately 10 min excluding warm-up duration.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were processed using the SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Results are presented as mean ± SD. The assumption of normality was confirmed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Test-retest reliability of measurements was assessed by the Cronbach interclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Firstly data were analysed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the association between baseline BP and the magnitude of BP decrease after the two interventions. Cohen’s d effect size (ES) was also calculated to determine the magnitude of changes or difference between interventions. ES was classified according to Cohen’s d as follows: < 0.2 was defined as trivial; 0.2– 0.6 was defined as small; >0.6–1.2 was defined as moderate; >1.2–2.0 was defined as large; > 2.0-4.0 was defined as very large; and >4.0 was defined as extremely large.

RESULTS

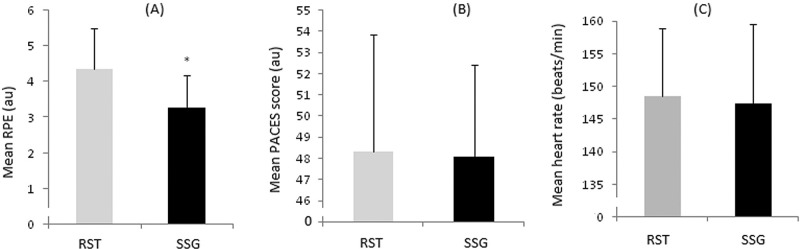

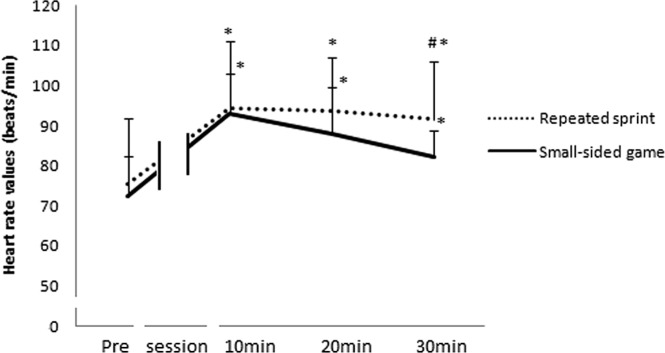

Participants’ baseline measures are presented in Table 1. Post-exercise blood pressure and heart rate after the two interventions are displayed in Table 2. Perceptual and enjoyment responses are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

TABLE 1.

Mean ± SD of age, body composition, blood pressure and maturity characteristics at baseline of the adolescent subjects.

| Variables | Values (M±SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 15.8 ± 0.6 |

| Y-PHV | 0.8 ± 0.5 |

| Height (m) | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

| Body mass (kg) | 59.1 ± 3.7 |

| Sum of skinfolds (mm) | 25.4 ± 2.8 |

| HR peak (beats/min) | 200 ± 5.6 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 113.2 ± 6.2 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 64.9 ± 1.5 |

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; Y-PHV: years to/from age of peak height velocity.

TABLE 2.

Effects of small-sided game and repeated sprint on BP and HR recovery (results presented as mean ± SD).

| Pre | 10 min | %Δ | ES | 20 min | % | ES | 30 min | %Δ | ES | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (beat/min) | ||||||||||

| RST | 75.5 ± 16.3 | 94.2 ± 16.8 | 24.8* | 1.1 | 93.5 ± 13.3 | 23.8* | 1.2 | 91.6 ± 14.3 | 21.3* | 1 |

| SSG | 72.4 ± 9.9 | 92.9 ± 10.2 | 28.3* | 2 | 88 ± 11.6 | 21.5* | 1.4 | 82.3 ± 6.5 | 13.6* # | 0.9 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | ||||||||||

| RST | 116.5 ± 8.6 | 116.7 ± 11 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 114.5 ± 5.9 | -1.7 | 0.48 | 115 ± 7.3 | -1.3 | 0.5 |

| SSG | 114.7 ± 6.9 | 112.4 ± 4.4 | -2 | 0.2 | 116 ± 9.1 | 1.2 | 0.27 | 112.7 ± 5.3 | -1.7 | 0.3 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | ||||||||||

| RST | 68.5 ±6.3 | 70.5 ± 5.7 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 69.3 ± 7.7 | 1.2 | 0.71 | 69.8 ± 7.2 | 1.9 | 0.6 |

| SSG | 68.8 ± 5.4 | 69.8 ± 6.2 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 66.8 ± 6.2 | -2.9 | 0.3 | 65 ± 6.2 | -5.5 | 0.7 |

Note: HR: heart rate, RS: repeated sprint, SSG: small-sided game; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure.

denotes significant difference compared with baseline (pre).

denotes significant difference between interventions.

FIG 1.

Differences between repeated sprint session (RST) and small-sided game session (SSG) in terms of rating of perceived exertion (A), physical activity enjoyment scale (B) and mean heart rate (C); *: denotes significant difference compared to baseline (p < 0.05).

FIG 2.

Heart rate data measured before (Pre) and after 10, 20 and 30 min of a repeated sprint training session (RST) or a small-sided game session (SSG). * Significantly different from Pre (P ≤ 0.05). # Significant difference between the two interventions (P ≤ 0.05).

The intra-class correlation coefficients for test-retest reliability (n = 8) were high for resting HR (r = 0.9, P<0.01), SBP (r = 0.8, P = 0.01) and DBP (r = 0.8, P = 0.01).

No significant change vs. baseline values was detected in SBP or DBP at 10, 20 and 30 min of post-exercise recovery after the two interventions (all P>0.05, ES<0.6). However, Pearson’s correlation revealed a significant large and inverse association between baseline BP and the magnitude of decline after RST and SSG. After an SSG session, a significant correlation was found for SBP at 10 min (r = -0.8, P = 0.01), at 30 min (r = -0.6, r = 0.04) and for DBP at 10 and 20 min (both r > 0.7, P < 0.05). After an RST session, a significant correlation was found for SBP at 20 min (r = -0.7, P = 0.01) and at 30 min (r = -0.6, r = 0.05); Table 3. In regard to HR, both sessions similarly induced significant increases after exercise compared with baseline. However, post-hoc analysis revealed significant lower values after SSG compared with RST at 30 min after interventions (82.3 ± 6.5 versus 91.6 ± 14.3 beats/min, P = 0.04, ES = 0.8, respectively). Finally, significantly lower RPE was noted after SSG compared with RST (P=0.02, ES=1.1), while perceived enjoyment scores did not differ between groups (P=0.92, ES=0.04).

TABLE 3.

Relationship between baseline BP and post-exercise changes.

| 10 min | 20 min | 30 min | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting SBP | SSG | r = -0.8 * P = 0.01 |

r = -0.2 P = 0.5 |

r = -0.6 * P = 0.04 |

| RST | r = 0.3 P = 0.4 |

r = -0.7* P = 0.01 |

r = -0.6* P = 0.05 |

|

| Resting DBP | SSG | r = -0.8* P = 0.01 |

r = -0.7* P = 0.02 |

r = -0.5 P = 0.1 |

| RST | r = -0.5 P = 0.1 |

r = -0.5 P = 0.1 |

r = -0.5 P = 0.1 |

|

Note: SSG - small-sided game, RST - repeated-sprint training

DISCUSSION

The present study sought to compare cardiovascular, effort-perception and enjoyment responses to small-sided soccer games compared with repeated sprint running in untrained healthy adolescents. The main findings are that the two training methods elicited similar exercise intensity, without any repercussion for post-exercise BP. The effort perception was significantly lower after SSG than RST, with no difference in the perceived enjoyment between groups. Furthermore, HR value declines after interventions were at similar magnitude during the first 20 min. However, HR values were significantly lower after SSG than RST at 30 min after intervention.

During the last few years, a growing body of research has highlighted the benefits of organized soccer training for health indicators in healthy or unhealthy young and adults individuals [28–30]. Although there is evidence demonstrating the efficacy of soccer training as a strategy to improve health status, specific research about the acute physiological and perceptual responses is scarce, especially in paediatric populations. Our findings demonstrated that SSG might elicit moderate to vigorous exercise intensity (over 70% HR peak), which is compatible with the improvement of aerobic capacity and equivalent to values previously reported for adults [31].

Furthermore, the % HR peak observed within exercise sessions was similar in SSG and RST, suggesting that high metabolic stress was provoked by both types of training.

It has been systematically shown that SBP and DBP can be reduced for several hours after a single session of resistance training [32] and aerobic-based training [33], which has been referred to as post-exercise hypotension. Furthermore, this response has been suggested to be clinically desirable, since chronic BP reduction due to aerobic training could be related to the summation of acute hypotensive responses following exercise sessions [34]. Since benefits of recreational soccer training for BP have been reported [29,35], we considered it relevant to test whether SSG and RST would be able to induce post-exercise hypotension. This hypothesis was not confirmed, since differences in SBP and DBP compared to pre-exercise values were not detected after either intervention at any of the time-points during recovery. So far, no other study has aimed to investigate the effects of recreational soccer on post-exercise BP, which limits the discussion of the present data. Nonetheless, the present findings concur with several prior studies that did not observe post-exercise hypotension in normotensive individuals [36,37]. Despite the fact that significant BP reduction was not detected after SSG and RST, our data corroborate the hypothesis of a relationship between resting BP and the magnitude of post-exercise hypotension. Despite the short period of BP assessment after exercise, in both SSG and RST, subjects who had higher initial BP exhibited greater reduction in BP (r>0.81, P < 0.05). In the present study, the subjects were healthy and of normal weight, which might have been related to the normal BP values that were observed at rest. Further studies should further develop the findings of the present research by controlling post-exercise blood pressure for more than 30 min post-exercise recovery. Furthermore, although the benefits of soccer-based training for resting BP have been demonstrated in healthy and hypertensive adults subjects [29,35], there are no data on the long-term effects of SSG on blood pressure in adolescents, and this should be addressed in future studies.

Heart rate values during the recovery period after the two interventions were significantly higher at 10, 20 and 30 min compared with baseline values. However, at 30 min, HR was significantly higher after RST compared with SSG, suggesting that RST may result in more post-exercise fatigue/stress than SSG. These results are in line with the study of Buchheit et al. [14]. These authors demonstrated that parasympathetic reactivation assessed through HR recovery and HR variability is highly impaired after RST exercise in moderately trained subjects and appears to be mainly related to the anaerobic processes that are highly taxed during RST. Thus, the low parasympathetic reactivation after RST and SSG should be taken into account by clinicians and specialists wishing to prescribe these two types of training especially in clinical patients.

It has been shown that motivation represents an important component to start doing physical activity; it is the first step and is particularly important in children and adolescents because they are strongly influenced by motivation and enjoyment of physical activity [38]. The SSG has been acknowledged as an effective tool for enhancing adherence to physical activity in untrained individuals. Furthermore, it represents a social activity which produces larger improvements in maximal oxygen uptake than continuous moderate-intensity endurance running or strength training [39]. Altogether, our findings suggest that both SSG and RST should be considered as strategies for replacing traditional continuous exercise training regimens, in order to counteract the lack of motivation, which is a key component in physical inactivity [40]. In regard to effort and enjoyment perception, the present results showed that SSG elicited significantly lower RPE than RST, but similar enjoyment (PACES). Since the exercise intensity was similar across the two types of exercise, a first analysis might suggest that the inferior fatigue perception during SSG is related to a higher level of motivation in practising soccer than performing repeated sprints. On the other hand, this could be questioned based on the fact that a significant difference in enjoyment score was not detected between exercise modes. Actually, previous studies have consistently shown that RST may be a motivating activity for adolescents, at least in comparison with continuous exercise [12,14]. Therefore, differences in fatigue perception could possibly be due to either physiological issues, such as the proportion of aerobic-anaerobic metabolism, or a combination of physiological and motivational aspects (such as the existence of goals and collective competition). Evidently, further research is warranted to evaluate these speculations.

Some limitations of the present study should be considered. Firstly the sample size is small, and thus it is difficult to draw a general conclusion. Furthermore, the two kinds of exercise were different in terms of motor recruitment and biomechanical aspects, and therefore future studies should include the assessment of the workload applied for both exercises, because it has been shown that differences in exercise workload may influence either metabolic or cardiorespiratory responses [41].

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the present study shows that SSG and RST elicited higher exercise intensity (HR values exceeds 70% of HRpeak). However, significant effects on BP up to 30 minutes after exercise were not detected. Furthermore, effort perception was significantly lower after SSG than RST, although the enjoyment level was similar across conditions. Additional research is necessary to investigate whether SSG and RST can induce post-exercise hypotension in adolescents with high resting BP, as well as to ascertain potential determinant factors of perceived fatigue and enjoyment within different types of activity in this population.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the students for their time and effort throughout the study.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflict of interests.

Disclosure statement

No author has any financial interest or received any financial benefit from this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lakka H-M, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, Niskanen LK, Kumpusalo E, Tuomilehto J, Salonen JT. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA. 2002;288(21):2709–2716. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.21.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laing S, Swerdlow A, Slater S, Burden A, Morris A, Waugh NR, Gatling W, Bingley PJ, Patterson CC. Mortality from heart disease in a cohort of 23,000 patients with insulin-treated diabetes. Diabetologia. 2003;46(6):760–765. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bigi S, Fischer U, Wehrli E, Mattle HP, Boltshauser E, Bürki S, Jeannet PY, Fluss J, Weber P, Nedeltchev K, El-Koussy M, Steinlin M, Arnold M. Acute ischemic stroke in children versus young adults. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(2):245–254. doi: 10.1002/ana.22427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maximova K, McGrath JJ, Barnett T, O’Loughlin J, Paradis G, Lambert M. Do you see what I see? Weight status misperception and exposure to obesity among children and adolescents. Int J Obes. 2008;32(6):1008–1015. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortega F, Ruiz J, Castillo M, Sjöström M. Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: a powerful marker of health. Int J Obes. 2008;32(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Telama R, Leskinen E, Yang X. Stability of habitual physical activity and sport participation: a longitudinal tracking study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1996;6(6):371–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1996.tb00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S, Han J, Jin Y, Lee I, Hong H, Kang H. Poor physical fitness is independently associated with mild cognitive impairment in elderly Koreans. Biol Sport. 2016;33(1):57–62. doi: 10.5604/20831862.1185889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodersen NH, Steptoe A, Boniface DR, Wardle J. Trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviour in adolescence: ethnic and socioeconomic differences. Br J sports Med. 2007;41(3):140–144. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.031138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leslie E, Owen N, Salmon J, Bauman A, Sallis JF, Lo SK. Insufficiently active Australian college students: perceived personal, social, and environmental influences. Prev Med. 1999;28(1):20–27. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Brown W. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: review and update. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(12):1996–2001. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasconcellos F, Seabra A, Katzmarzyk PT, Kraemer-Aguiar LG, Bouskela E, Farinatti P. Physical activity in overweight and obese adolescents: Systematic review of the effects on physical fitness components and cardiovascular risk factors. Sports Med. 2014;44(8):1139–1152. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartlett JD, Close GL, MacLaren DP, Gregson W, Drust B, Morton JP. High-intensity interval running is perceived to be more enjoyable than moderate-intensity continuous exercise: implications for exercise adherence. J Sports Sci. 2011;29(6):547–553. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2010.545427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaister M. Multiple-sprint work: methodological, physiological, and experimental issues. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2008;3(1):107–112. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.3.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchheit M, Laursen PB, Ahmaidi S. Parasympathetic reactivation after repeated sprint exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293(1):133–141. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00062.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahdiabadi J, Gaeini AA, Kazemi T, Mahdiabadi M. The effect of aerobic continuous and interval training on left ventricular structure and function in male non-athletes. Biol Sport. 2013;30(3):207–211. doi: 10.5604/20831862.1059302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammami A Chamari K, Slimani M, Shephard RJ, Yousfi N, Tabka Z, Bouhlel E. Effects of recreational soccer on physical fitness and health indices in sedentary healthy and unhealthy subjects. Biol Sport. 2016;33(2):127–137. doi: 10.5604/20831862.1198209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faude O, Kerper O, Multhaupt M, Winter C, Beziel K, Junge A, Meyer T. Football to tackle overweight in children. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(s1):103–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milanović Z, Pantelić S, Kostić R, Trajković N, Sporiš G. Soccer vs. running training effects in young adult men: which programme is more effective in improvement of body composition? Randomized controlled trial. Biol Sport. 2015;32(4):301–305. doi: 10.5604/20831862.1163693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bangsbo J, Hansen PR, Dvorak J, Krustrup P. Recreational football for disease prevention and treatment in untrained men: a narrative review examining cardiovascular health, lipid profile, body composition, muscle strength and functional capacity. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(9):568–576. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirwald RL, Baxter-Jones AD, Bailey DA, Beunen GP. An assessment of maturity from anthropometric measurements. Med Sci Sports Exer. 2002;34(4):689–694. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200204000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bangsbo J, Iaia FM, Krustrup P. The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test. Sports med. 2008;38(1):37–51. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Póvoas SC, Castagna C, Soares JM, Silva PM, Lopes MV, Krustrup P. Reliability and validity of Yo-Yo tests in 9-to 16-year-old football players and matched non-sports active schoolboys. Eur J Sport Sci. 2015;16(7):1–9. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2015.1119197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickering T, Hall J, Appel L, Falkner B, Graves J, Hill M, Jones D, Kurtz T, Sheps S, Roccella E. Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005;45:142–161. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster C, Florhaug JA, Franklin J, Gottschall L, Hrovatin LA, Parker S, Doleshal P, Dodge C. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J Strength Cond Res. 2001;15(1):109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Motl RW, Dishman RK, Saunders R, Dowda M, Felton G, Pate RR. Measuring enjoyment of physical activity in adolescent girls. Am J Preventive Med. 2001;21(2):110–117. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rampinini E, Impellizzeri FM, Castagna C, Abt G, Chamari K, Sassi A, Marcora SM. Factors influencing physiological responses to small-sided soccer games. J Sports Sci. 2007;25(6):659–666. doi: 10.1080/02640410600811858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchheit M, Millet G, Parisy A, Pourchez S, Laursen P, Ahmaidi S. Supramaximal training and postexercise parasympathetic reactivation in adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(2):362–371. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815aa2ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barene S, Krustrup P, Jackman SR, Brekke OL, Holtermann A. Do soccer and Zumba exercise improve fitness and indicators of health among female hospital employees? A 12-week RCT. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(6):990–999. doi: 10.1111/sms.12138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohr M, Lindenskov A, Holm P, Nielsen H, Mortensen J, Weihe P, Krustrup P. Football training improves cardiovascular health profile in sedentary, premenopausal hypertensive women. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(s1):36–42. doi: 10.1111/sms.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vasconcellos F, Seabra A, Cunha F, Montenegro R, Penha J, Bouskela E, Nogueira Neto JF, Collett-Solberg P, Farinatti P. Health markers in obese adolescents improved by a 12-week recreational soccer program: a randomised controlled trial. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(6):564–575. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1064150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aslan A. Cardiovascular responses, perceived exertion and technical actions during small-sided recreational soccer: Effects of pitch size and number of players. J Hum kinet. 2013;38:95–105. doi: 10.2478/hukin-2013-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boroujerdi SS, Rahimi R, Noori SR. Effect of high-versus low-intensity resistance training on post-exercise hypotension in male athletes. Int SportMed J. 2009;10(2):95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eicher JD, Maresh CM, Tsongalis GJ, Thompson PD, Pescatello LS. The additive blood pressure lowering effects of exercise intensity on post-exercise hypotension. Am Heart J. 2010;160(3):513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu S, Goodman J, Nolan R, Lacombe S, Thomas SG. Blood pressure responses to acute and chronic exercise are related in prehypertension. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(9):1644–1652. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31825408fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Randers MB, Nielsen JJ, Krustrup BR, Sundstrup E, Jakobsen MD, Nybo L, Dvorak J, Bangsbo J, Krustrup P. Positive performance and health effects of a football training program over 12 weeks can be maintained over a 1-year period with reduced training frequency. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(s1):80–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rondon MUPB, Alves MJN, Braga AMF, Teixeira OTU, Barretto AC, Krieger EM, Negrao CE. Postexercise blood pressure reduction in elderly hypertensive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(4):676–682. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01789-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brownley KA, West SG, Hinderliter AL, Light KC. Acute aerobic exercise reduces ambulatory blood pressure in borderline hypertensive men and women. Am J Hypertens. 1996;9(3):200–206. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)00335-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seabra AC, Seabra AF, Mendonça DM, Brustad R, Maia JA, Fonseca AM, Malina RM. Psychosocial correlates of physical activity in school children aged 8–10 years. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(5):794–798. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milanović Z, Pantelić S, Čović N, Sporiš G, Krustrup P. Is Recreational Soccer Effective for Improving VO2max? A Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis. Sports Med. 2015;45(9):1339–1353. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0361-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cox AE, Smith AL, Williams L. Change in physical education motivation and physical activity behavior during middle school. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(5):506–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tschakert G, Kroepfl J, Mueller A, Moser O, Groeschl W, Hofmann P. How to regulate the acute physiological response to “aerobic” high-intensity interval exercise. J Sports Sci Med. 2015;14(1):29–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]