Abstract

Drug-induced gingival overgrowth (DIGO) is a well-recognized adverse effect of certain systemic medications. Calcium channel blockers, anticonvulsants, and immunosuppressants are frequently implicated drugs in the etiology of DIGO. Drug variables, plaque-induced inflammation, and genetic factors are the three important factors in the expression of gingival changes after systemic medication use. Careful clinical examination and thorough history taking form the basis for diagnosis of DIGO. Histopathological examination is often neglected; however, it is an important aid that helps in differential diagnosis. Cessation or change of drug and meticulous plaque control often leads to regression of the lesion, which however might need surgical correction for optimal maintenance of gingival health. The purpose of the present article is to review case reports and case series published in the last two decades and to assimilate and compile the information for clinical applications such as diagnosis and therapeutic management of DIGO.

Keywords: Anticonvulsants, calcium channel blockers, dental plaque, drug-induced gingival overgrowth, genetic factors, immunosuppressants, oral hygiene

INTRODUCTION

Certain gingival diseases that are modified substantially by the use of systemic medications are now well recognized. In the 1999 international workshop for a classification of periodontal diseases and conditions, “drug-influenced gingival enlargements” have been identified and added as a subcategory under the section “dental plaque-induced gingival diseases.”[1] Drug-influenced gingival enlargement has been defined as “an overgrowth or increase in size of the gingiva resulting in whole or in part from systemic drug use.”[2]

Anticonvulsants such as phenytoin and immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine and calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are frequently implicated as drugs that cause gingival overgrowth.[3] In addition, drugs such as sodium valproate[4] and erythromycin[5] induced gingival enlargements have also been reported in the past. Although the chemical nature of the three drug groups is different, they have a similar mechanism of action at the cellular level, where they inhibit intracellular calcium ion influx. Thus, all these drugs, despite being dissimilar, have a common side effect upon secondary target tissue such as gingival connective tissue.[6]

Drug-induced gingival overgrowth (DIGO) is usually esthetically disfiguring and interferes with speech and mastication. The clinical characteristics common to all DIGOs include a variation in the inter- or intra-patient pattern of enlargement; a tendency to occur more often in the anterior gingiva; a higher prevalence in younger age groups; onset within 3 months of drug use; and no association with attachment loss or tooth mortality. Moreover, the clinical lesions and their histological characteristics are indistinguishable among the gingival enlargements induced by one drug to another.[7] Age and other demographic variables, drug variables, concomitant medications, periodontal variables, and genetic factors are the known risk factors for DIGO.[3]

Although adequate literature is available in the form of case reports and case series, a lacunae still exists in assimilation and compilation of this knowledge for clinical application. Hence, in the present article, an attempt is being made to review case reports and case series of drug-induced gingival enlargements to outline the different drugs that induce gingival overgrowth, their varied clinical presentations, possible pathogenic mechanisms involved, their diagnosis and therapeutic managements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A thorough Medline/PubMed search was done for articles published from January 1993 to December 2014 using the search terms “gingival enlargement,” “gingival overgrowth,” “gingival hyperplasia,” “drug-induced,” “drug-influenced,” “medication-induced,” “medication-influenced,” and “DIGO” in various combinations. The search has been carried out by two separate investigators and then compared, analyzed, discussed, and agreed upon by the entire team of investigators before inclusion of the articles in the study.

Only human case reports and case series of DIGOs published in English were considered for inclusion in the article.

Exclusion criteria

Studies published in languages other than English

Reports of gingival enlargements in nonhuman subjects (DIGO reports in animals)

Exclusive review of literature articles

Exclusive histopathological analysis without clear reporting of the case

In vitro studies

Epidemiological studies, including prevalence studies, case–control studies, cohort studies, and therapeutic efficacy studies.

Reports of gingival enlargement with any etiology other than “drug-induced” or of uncertain etiology.

Inclusion criteria

Case reports and case series publications of DIGO involving human subjects

Articles published in English alone between January 1993 and December 2014.

RESULTS

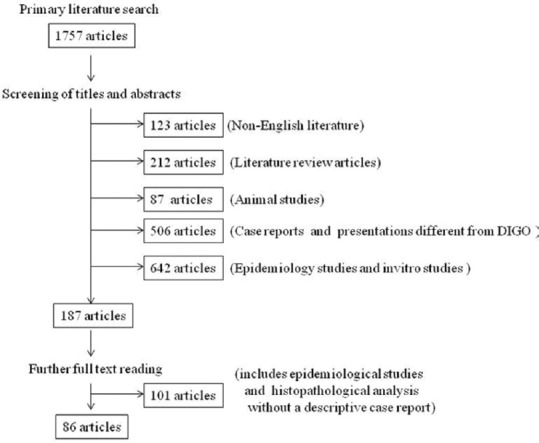

The primary literature search identified 1757 potential articles. However, by thorough screening of titles and abstracts, and further full text reading, only 86 relevant articles could be identified, which included case reports and case series presentations of DIGOs. Altogether, the number of cases analyzed was 119 [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of “literature search”

Reported cases of gingival enlargements were induced by different drugs; CCBs (50/119 – of which amlodipine-25;[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] nifedipine-13;[26,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40] verapamil-4;[41] felodipine-2;[42,43] nisoldipine-1;[44] manidipine-1;[45] and unspecified CCBs-4[46]); phenytoin (11/119);[47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] cyclosporine (31/119);[35,46,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75] phenobarbital (4/119);[76,77,78] sodium valproate (3/119 - including one report of congenital drug-induced gingival hyperplasia);[79,80,81] d-penicillamine (2/119);[82] combination oral contraceptive pill-lynestrenol and ethinyl estradiol (1/119);[83] vigabatrin (1/119).[84] Cases of gingival enlargement after combination drug therapy have also been reported; a combination of cyclosporine and CCBs (11/119);[35,46,85,86,87,88] phenytoin and phenobarbital (4/119);[54,89,90,91] and a combination of phenytoin, cyclosporine, and CCBs (1/119).[92]

Two cases of DIGO around dental implants have been reported; one associated with nifedipine use,[37] and other with phenytoin use.[57]

DISCUSSION

Gingival overgrowth is a frequently encountered, unrelated adverse effect resulting from intake of certain systemic drugs. An understanding of the underlying factors and mechanisms involved might be needful in prevention and therapeutic management of DIGO. Seymour et al. in 1996[93] suggested that DIGO is multifactorial and that three factors are significant in its expression. They are drug variables, plaque-induced inflammatory changes in the gingival tissues, and genetic factors.

Drug variables

From the reported cases in the last two decades assessed in this review, it has been clear that CCBs, cyclosporine, and phenytoin are the attributing drugs for a majority of DIGO cases.

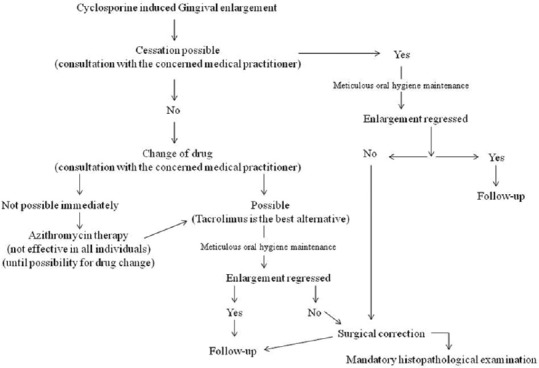

Cyclosporine is an immunosuppressant reportedly used in kidney/heart/liver transplant patients to prevent organ rejection.[35,60,61,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,72,74,75] It has also been used for treating aplastic anemia,[58,60,73] psoriasis,[62] and Behcet disease.[71] Cyclosporine is known to alter the metabolism of gingival fibroblasts and also upregulates specific growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor B, thereby causing adverse gingival changes such as overgrowth.[6] Cessation of the drug or its substitution by another drug is a definitive step in the management of cyclosporine-associated gingival overgrowth. Mathur et al. in 2003[65] reported regression of gingival overgrowth in a renal transplant patient after cessation of cyclosporine. Similarly, V'lckova-Laskoska in 2005[62] reported virtually complete reduction of gingival enlargement after cessation of cyclosporine in a patient under treatment for psoriasis.

However, abrupt cessation of an immunosuppressant might lead to severe complications such as failure of organ transplantations. Hence, substitution of cyclosporine by a better alternative has been suggested. Kennedy and Linden in 2000[72] and Hernández et al. in 2003[66] reported rapid reduction in gingival overgrowth after cyclosporine withdrawal and its conversion to tacrolimus in organ transplant patients. Similarly, Gonçalves et al. in 2008[60] reported that DIGO in a 9-year-old renal transplant patient under cyclosporine therapy recurred even after surgical correction and thorough practice of plaque control measures, which however regressed on change of medication from cyclosporine to tacrolimus without any need for further surgical intervention. Furthermore, Macartney et al. in 2009[59] reported that gingival enlargement in a child with severe aplastic anemia under cyclosporine therapy did not respond to intensive dental intervention. Significant improvement in gingival hyperplasia could only be achieved after the immunosuppressive therapy was changed to tacrolimus.

Besides cessation and change of drug, short-term administration of azithromycin was reported to improve cyclosporine-associated gingival hyperplasia by Wahlstrom et al. in 1995[75] and Strachan et al. in 2003.[67] Azithromycin may improve the symptoms of cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth by inhibiting cyclosporine-induced cell proliferation and collagen production and also by activating matrix metalloproteinases in cyclosporine-treated fibroblasts.[94] However, Nowicki et al. in 1998[74] reported only a partial regression of gingival hyperplasia with azithromycin in cyclosporine-treated renal transplant patients and could not find any further improvement with repeated azithromycin administration. In addition, Vallejo et al. in 2001[73] reported no improvement in cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia in spite of administering azithromycin. They further reported complete remission of gingival hyperplasia, only after withdrawal of cyclosporine and its replacement with tacrolimus. Thus, certain cases of cyclosporine-induced hyperplasia are resistant to azithromycin and this could probably be explained on the basis of varying fibroblast subpopulations in different individuals. Drug substitution by alternative immunosuppressants such as tacrolimus remains to be current definitive viable option in the management of cyclosporine-associated gingival hyperplasia.

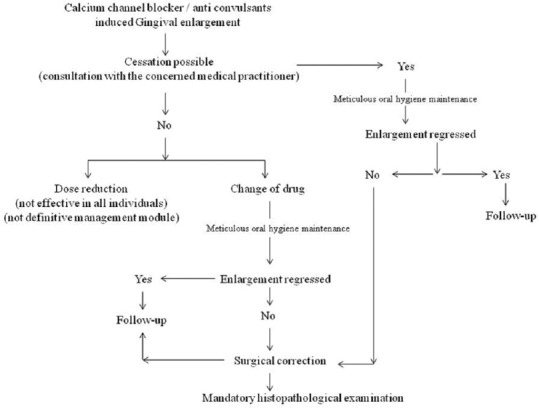

CCBs are therapeutic agents that are used in the management of heart diseases, particularly hypertension. CCBs affect calcium metabolism by reducing Ca2+ cell influx, which in turn reduces uptake of folic acid and leads to reduced production of active collagenase.[95] Among CCBs, nifedipine is the most frequently implicated drug, inducing gingival overgrowth.[95] However, in the last two decades, more cases of gingival overgrowth have been reported after amlodipine use than nifedipine (25 cases of amlodipine as against 13 cases of nifedipine). Low doses and short-term administration of CCBs might also induce gingival hyperplasia as suggested by Lafzi et al. in 2006[21] and Joshi and Bansal in 2013.[10] Furthermore, a case report by Sunil et al. in 2012[29] suggests that severity of the enlargement is dose dependent.

Changes of drug and meticulous oral hygiene are important aspects in the management of CCB-associated gingival overgrowth. Aldemir et al. in 2012[12] reported a case of gingival overgrowth in a hypertensive patient under amlodipine therapy, in which, change of medication resulted in regression of the overgrowth within 3 months without any need for surgical intervention. Joshi and Bansal in 2013[10] reported that gingival overgrowth in a hypertensive patient under amlodipine therapy showed drastic improvement within 1.5 months after change of drug. Similarly, Ramsdale et al. in 1995[36] reported gingival hyperplasia in a patient with heart disease under long-term nifedipine therapy, which disappeared completely within 6 months after cessation of nifedipine use. On the contrary, D'Errico and Albanese in 2013[8] reported a case of gingival overgrowth in a hypertensive patient under amlodipine therapy, where changing drug and execution of a professional oral hygiene treatment did not allow resolution of the hyperplasia. Only surgical excision of the overgrowth permitted resolution of the case. Leaving the two extremities apart, majority of cases were managed by change of drug and meticulous plaque control, which resulted in moderate regression of the lesion. This was followed by surgical correction of gingival tissues for optimal gingival health and maintenance.

Phenytoin is the most commonly prescribed anticonvulsant agent in the management of epilepsy. Phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth is the earliest known DIGO; first case of which was reported in 1939 by Kimball.[96] Phenytoin affects metabolism of certain fibroblast subpopulations, intracellular calcium metabolism, reduces folic acid uptake and metabolism, leading to production of inactive collagenase; thus, leading to gingival overgrowth.[6]

Although rare, besides gingival hyperplasia, phenytoin is also known to induce mucosal hyperplasia in denture wearers.[97] Dhingra and Prakash in 2012[89] reported a rare case of enlargement of mucosa in partially edentulous alveolar ridges despite not using any denture, after combination therapy of phenytoin and phenobarbital for epilepsy. Chee and Jansen in 1994[57] reported a case of peri-implant tissue hyperplasia after phenytoin therapy for epilepsy.

The management of phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth is similar to that of other DIGOs. Withdrawal and change of drug, meticulous oral hygiene maintenance, conservative nonsurgical approach followed by surgical intervention if necessary are the sequential steps in the treatment of phenytoin-associated gingival hyperplasia.

Polypharmacy can have an effect on DIGO. Majority of conditions need a combination therapy, particularly organ transplant patients receiving immunosuppressants are frequently administered CCBs to prevent serious life-threatening complications. However, such concomitant medications have a significant synergistic effect on gingival changes and increase the chances of recurrence.[98]

Plaque-induced inflammatory changes

Majority of DIGO cases are reported in patients with poor oral hygiene maintenance. However, whether plaque is a contributing factor to gingival hyperplasia or a consequence of gingival hyperplasia is not yet clearly outlined. Nevertheless, the clinical and histological picture of gingival enlargement and the medical history of the patient led some investigators to diagnose the enlargement as a combination of inflammatory and DIGO.[4] Addition of inflammatory component to the gingival overgrowth, thus complicates the diagnosis and also the management of DIGO.

Nonsurgical management of DIGO includes professionally delivered scaling and root planing as well as instructing and reinforcing oral hygiene maintenance measures to the patient. This, in conjunction with drug change, may totally eliminate the overgrowth or might at least partially result in regression of the lesion, allowing for an easy surgical correction.[99]

Genetic factors

Genotypic variation among individuals was attributed to the observed inter-individual variability in the expression and presentation of gingival hyperplasia after using systemic medications. Gingival fibroblasts exhibit marked functional heterogeneity in response to various stimuli.[93] This probably could explain why, not all individuals subjected to medications inducing gingival hyperplasia show gingival changes. Babu et al. in 2013[47] evaluated drug metabolizing enzyme cytochrome P450 2C9 gene polymorphism in an epileptic patient under phenytoin therapy who presented with generalized gingival enlargement. The pharmacogenomic study of the patient revealed that the patient was a homozygous mutant of CYP2C9 which prompted them to substitute the drug. Similarly, Charles et al. in 2012[13] reported a case of amlodipine-induced gingival hyperplasia associated with MDR1 3435C/T gene polymorphism. This gene polymorphism was suggested to alter the inflammatory response of the gingival tissues to the drug. Thus, pharmacogenomic studies might be useful in determining the effects of a drug and also help in prompting the physician to choose correct dose of drug or other alternatives.

The analysis of case reports in this article also revealed the importance of histopathological examination of the DIGO lesions. Kim et al. in 2002[69] reported two cases of cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth. However, the histopathological examination of the excised gingival tissues was suggestive of plasma cell granuloma composed of mature plasma cells. Thus, a careful differential diagnosis from malignant plasmacytoma had to be made in those cases. Another report by Rolland et al. in 2004[64] presented two cases of gingival overgrowth in heart transplant patients under cyclosporine therapy. The histologic picture of the excised tissue showed diffuse lamina propria infiltration by large malignant-appearing lymphoid cells. Subsequently, a diagnosis of posttransplant lympho-proliferative disorders was suggested.

In yet another report, Yoon et al. in 2006[22] presented a case of gingival enlargement in a patient who had been under long-term amlodipine therapy. Histopathological examination of an incisional gingival biopsy of the lesion revealed neoplastic cells. Further immunohistochemical study yielded a diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma. Later, a bone marrow biopsy was performed and the diagnosis was changed to acute myeloid leukemia. Unfortunately, the patient never showed remission and died 4 months after initial diagnosis. da Silveira et al. in 2007[90] reported a case of gingival enlargement in a patient under long-term phenytoin and phenobarbital therapy who also presented a peripheral calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor which could be confused with fibrous hyperplasia. Vishnudas et al. in 2014[28] reported a gingival enlargement after amlodipine use, which on histopathological examination was identified as plasma cell granuloma. These above reported cases clearly signify the importance of histopathological examination of gingival tissues in the diagnosis and management of DIGO.

Significant findings of the review

Besides gingiva, drug-induced hyperplasias of edentulous mucosa and peri-implant mucosa have also been reported (although rare)

Azithromycin therapy for cyclosporine-induced gingival enlargement is not a definitive management module

Tacrolimus is the best alternative substitute (available till date) for cyclosporine as an immunosuppressant to avoid/treat gingival hyperplasia

Meticulous oral hygiene maintenance is a critical factor in regression of DIGO

Persisting enlargement after drug cessation/substitution and meticulous oral hygiene maintenance might require surgical excision

Histopathological examination of all persisting enlargements is mandatory to evaluate malignant changes

Incidence of DIGO is believed to be influenced by genotype of the individual. This signifies the need for transformation to the concept of personalized medicine to prevent DIGO. Further research is, however, needed for such transformation in medicine to be practiced

Figure 2.

Treatment recommendation flowchart for cyclosporine-induced drug-induced gingival overgrowth

Figure 3.

Treatment recommendation flowchart for calcium channel blocker/anticonvulsants-induced drug-induced gingival overgrowth

CONCLUSION

DIGO is a multifactorial adverse effect of taking certain systemic medications. Although exact pathogenic mechanisms are not yet completely understood, the drug variables, dental-plaque induced inflammatory changes, and genetic variables are frequently listed as important risk factors for DIGO. Careful selection of drug and its dose for particular medical conditions by medical practitioners might be helpful in preventing drug-related adverse effects. In cases, where using drugs that induce gingival overgrowth is unavoidable, dental referral, thorough plaque control, reinforcement of oral hygiene maintenance instructions to the patient might be helpful in preventing as well as controlling the severity of the lesion. An in-depth knowledge of pharmacokinetics of the drugs, their adverse effects, pathogenic mechanisms involved in DIGO and their varied clinical presentations helps the dental practitioner in therapeutic management of DIGO. In addition, coordination between medical and dental practitioners is essential for successful management of DIGO.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.4th ed. Chicago, IL: American Academy of Periodontology; 2001. American Academy of Periodontology. Glossary of Periodontal Terms. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seymour RA. Effects of medications on the periodontal tissues in health and disease. Periodontol 2000. 2006;40:120–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behari M. Gingival hyperplasia due to sodium valproate. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:279–80. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.54.3.279-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valsecchi R, Cainelli T. Gingival hyperplasia induced by erythromycin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallmon WW, Rossmann JA. The role of drugs in the pathogenesis of gingival overgrowth. A collective review of current concepts. Periodontol 2000. 1999;21:176–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mariotti A. Dental plaque-induced gingival diseases. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:7–19. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Errico B, Albanese A. Drug-induced gingival hyperplasia, treatment with diode laser. Ann Stomatol (Roma) 2013;4(Suppl 2):14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasupuleti MK, Musalaiah SV, Nagasree M, Kumar PA. Combination of inflammatory and amlodipine induced gingival overgrowth in a patient with cardiovascular disease. Avicenna J Med. 2013;3:68–72. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.118462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joshi S, Bansal S. A rare case report of amlodipine-induced gingival enlargement and review of its pathogenesis. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:138248. doi: 10.1155/2013/138248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muralikrishna T, Kalakonda B, Gunupati S, Koppolu P. Laser-Assisted Periodontal Management of Drug-Induced Gingival Overgrowth under General Anesthesia: A Viable Option. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:387453. doi: 10.1155/2013/387453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aldemir NM, Begenik H, Emre H, Erdur FM, Soyoral Y. Amlodipine-induced gingival hyperplasia in chronic renal failure: A case report. Afr Health Sci. 2012;12:576–8. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v12i4.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charles N, Ramesh V, Babu KS, Premalatha B. Gene polymorphism in amlodipine induced gingival hyperplasia: A case report. J Young Pharm. 2012;4:287–9. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.104375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma S, Sharma A. Amlodipine-induced gingival enlargement – A clinical report. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2012;33:e78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banthia R, Jain P, Banthia P, Belludi S, Jain AK. Amlodipine- induced gingival overgrowth: A case report. J Mich Dent Assoc. 2012;94:48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srivastava AK, Kundu D, Bandyopadhyay P, Pal AK. Management of amlodipine-induced gingival enlargement: Series of three cases. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2010;14:279–81. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.76931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Triveni MG, Rudrakshi C, Mehta DS. Amlodipine-induced gingival overgrowth. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2009;13:160–3. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.60231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubrey SW, Grocott-Mason R. Gingival overgrowth secondary to amlodipine. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2009;70:538–9. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2009.70.9.43877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhale RP, Phadnaik MB. Conservative management of amlodipine influenced gingival enlargement. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2009;13:41–3. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.51894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatia V, Mittal A, Parida AK, Talwar R, Kaul U. Amlodipine induced gingival hyperplasia: A rare entity. Int J Cardiol. 2007;122:e23–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lafzi A, Farahani RM, Shoja MA. Amlodipine-induced gingival hyperplasia. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11:E480–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoon AJ, Pulse C, Cohen LD, Lew TA, Zegarelli DJ. Myeloid sarcoma occurring concurrently with drug-induced gingival enlargement. J Periodontol. 2006;77:119–22. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.77.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obiechina NS, Fine JB. Case report: Treatment of amlodipine associated gingival overgrowth in periodontitis patients. Dent Today. 2000;19:76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morisaki I, Dol S, Ueda K, Amano A, Hayashi M, Mihara J. Amlodipine-induced gingival overgrowth: Periodontal responses to stopping and restarting the drug. Spec Care Dentist. 2001;21:60–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2001.tb00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seymour RA, Ellis JS, Thomason JM, Monkman S, Idle JR. Amlodipine-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:281–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Straka M, Varga I, Erdelský I, Straka-Trapezanlidis M, Krnoulová J. Drug-induced gingival enlargement. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2014;35:567–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tejnani A, Gandevivala A, Bhanushali D, Gourkhede S. Combined treatment for a combined enlargement. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18:516–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.138747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vishnudas B, Sameer Z, Shriram B, Rekha K. Amlodipine induced plasma cell granuloma of the gingiva: A novel case report. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2014;5:472–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.136267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sunil PM, Nalluswami JS, Sanghar SJ, Joseph I. Nifedipine-induced gingival enlargement: Correlation with dose and oral hygiene. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2012;4(Suppl 2):S191–3. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.100268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shibukawa Y, Fujinami K, Yamashita S. Clinical case report of long-term follow-up in type-2 diabetes patient with severe chronic periodontitis and nifedipine-induced gingival overgrowth. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2012;53:91–9. doi: 10.2209/tdcpublication.53.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alandia-Roman CC, Tirapelli C, Ribas P, Panzeri H. Drug-induced gingival overgrowth: A case report. Gen Dent. 2012;60:312–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fornaini C, Rocca JP. Co2 laser treatment of drug-induced gingival overgrowth – Case report. Laser Ther. 2012;21:39–42. doi: 10.5978/islsm.12-CR-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Carvalho Farias B, Cabral PA, Gusmão ES, Jamelli SR, Cimões R. Non-surgical treatment of gingival overgrowth induced by nifedipine: A case report on an elderly patient. Gerodontology. 2010;27:76–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2009.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naidoo LC, Stephen LX. Nifedipine-induced gingival hyperplasia: Non-surgical management of a patient. Spec Care Dentist. 1999;19:29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1999.tb01365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santi E, Bral M. Effect of treatment on cyclosporine- and nifedipine-induced gingival enlargement: Clinical and histologic results. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1998;18:80–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramsdale DR, Morris JL, Hardy P. Gingival hyperplasia with nifedipine. Br Heart J. 1995;73:115. doi: 10.1136/hrt.73.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silverstein LH, Koch JP, Lefkove MD, Garnick JJ, Singh B, Steflik DE. Nifedipine-induced gingival enlargement around dental implants: A clinical report. J Oral Implantol. 1995;21:116–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henderson JS, Guillot JL, Krolls SO, Parkel CO, Jr, Johnson RB. Case presentation. Initiation of gingival overgrowth by an increased daily dosage of nifedipine. Miss Dent Assoc J. 1994;50:12–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hapak L. Periodontal management of nifedipine-induced gingival overgrowth: A case report and review of the pertinent literature. Oral Health. 1994;84:15–7. 20-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sam G, Sebastian SC. Nonsurgical management of nifedipine induced gingival overgrowth. Case Rep Dent. 2014;2014:741402. doi: 10.1155/2014/741402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matharu MS, van Vliet JA, Ferrari MD, Goadsby PJ. Verapamil induced gingival enlargement in cluster headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:124–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.024240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fay AA, Satheesh K, Gapski R. Felodipine-influenced gingival enlargement in an uncontrolled type 2 diabetic patient. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1217. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.7.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young PC, Turiansky GW, Sau P, Liebman MD, Benson PM. Felodipine-induced gingival hyperplasia. Cutis. 1998;62:41–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tajani AH, Nesbitt SD. Gingival hyperplasia in a patient with hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:863–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.00036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ikawa K, Ikawa M, Shimauchi H, Iwakura M, Sakamoto S. Treatment of gingival overgrowth induced by manidipine administration. A case report. J Periodontol. 2002;73:115–22. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dannewitz B, Krieger JK, Simon I, Dreyhaupt J, Staehle HJ, Eickholz P. Full-mouth disinfection as a nonsurgical treatment approach for drug-induced gingival overgrowth: A series of 11 cases. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2010;30:63–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Babu SP, Ramesh V, Samidorai A, Charles NS. Cytochrome P450 2C9 gene polymorphism in phenytoin induced gingival enlargement: A case report. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2013;5:237–9. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.116828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parwani RN, Parwani SR. Management of phenytoin-induced gingival enlargement: A case report. Gen Dent. 2013;61:61–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohan RP, Rastogi K, Bhushan R, Verma S. Phenytoin-induced gingival enlargement: A dental awakening for patients with epilepsy. BMJ Case Rep 2013. 2013:pii: Bcr2013008679. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-008679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luvizuto ER, da Silva JB, Campos N, Luvizuto GC, Poi WR, Panzarini SR. Functional aesthetic treatment of patient with phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e174–6. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824de16e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Devanna R, Asif K. Interdisciplinary management of a patient with a drug-induced gingival hyperplasia. Contemp Clin Dent. 2010;1:171–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.72786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Oliveira Guaré R, Costa SC, Baeder F, de Souza Merli LA, Dos Santos MT. Drug-induced gingival enlargement: Biofilm control and surgical therapy with gallium-aluminum-arsenide (GaAlAs) diode laser – A 2-year follow-up. Spec Care Dentist. 2010;30:46–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2009.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lucchesi JA, Cortelli SC, Rodrigues JA, Duarte PM. Severe phenytoin-induced gingival enlargement associated with periodontitis. Gen Dent. 2008;56:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marakoglu I, Gursoy UK, Cakmak H, Marakoglu K. Phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth in un-cooperated epilepsy patients. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:337–40. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma S, Dasroy SK. Images in clinical medicine. Gingival hyperplasia induced by phenytoin. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:325. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tigaran S. A 15-year follow-up of phenytoin-induced unilateral gingival hyperplasia: a case report. Acta Neurol Scand. 1994;90:367–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb02739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chee WW, Jansen CE. Phenytoin hyperplasia occurring in relation to titanium implants: A clinical report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1994;9:107–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sabnis GR, Karnik ND, Sundar U, Adwani S. Gingival enlargement due to Cyclosporine A therapy in aplastic anaemia. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43:613–4. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.84988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Macartney C, Freilich M, Odame I, Charpentier K, Dror Y. Complete response to tacrolimus in a child with severe aplastic anemia resistant to cyclosporin A. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52:525–7. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gonçalves SC, Díaz-Serrano KV, de Queiroz AM, Palioto DB, Faria G. Gingival overgrowth in a renal transplant recipient using cyclosporine A. J Dent Child (Chic) 2008;75:313–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haytac CM, Ustun Y, Essen E, Ozcelik O. Combined treatment approach of gingivectomy and CO2 laser for cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth. Quintessence Int. 2007;38:e54–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.V'lckova-Laskoska MT. Cyclosporin A-induced gingival hyperplasia in psoriasis: Review of the literature and case reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2005;13:108–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Giusto TJ. Periodontal management of gingival overgrowth in a renal transplant patient: A case report. J N J Dent Assoc. 2005;76:26–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rolland SL, Seymour RA, Wilkins BS, Parry G, Thomason JM. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders presenting as gingival overgrowth in patients immunosuppressed with ciclosporin. A report of two cases. Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:581–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mathur H, Moretti AJ, Flaitz CM. Regression of cyclosporia-induced gingival overgrowth upon interruption of drug therapy. Gen Dent. 2003;51:159–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hernández G, Arriba L, Frías MC, de la Macorra JC, de Vicente JC, Jiménez C, et al. Conversion from cyclosporin A to tacrolimus as a non-surgical alternative to reduce gingival enlargement: A preliminary case series. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1816–23. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.12.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Strachan D, Burton I, Pearson GJ. Is oral azithromycin effective for the treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia in cardiac transplant recipients? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2003;28:329–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2003.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guelmann M, Britto LR, Katz J. Cyclosporin-induced gingival overgrowth in a child treated with CO2 laser surgery: A case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2003;27:123–6. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.27.2.v70187716x08286q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim SS, Eom D, Huh J, Sung IY, Choi I, Ryu SH, et al. Plasma cell granuloma in cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth: A report of two cases with immunohistochemical positivity of interleukin-6 and phospholipase C-gamma1. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:704–7. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.5.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Butterworth C, Chapple I. Drug-induced gingival overgrowth: A case with auto-correction of incisor drifting. Dent Update. 2001;28:411–6. doi: 10.12968/denu.2001.28.8.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Irshied J, Bimstein E. Oral diagnosis of Behcet disease in an eleven-year old girl and the non-surgical treatment of her gingival overgrowth caused by cyclosporine. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2001;26:93–8. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.26.1.e2g5662851133t35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kennedy DS, Linden GJ. Resolution of gingival overgrowth following change from cyclosporin to tacrolimus therapy in a renal transplant patient. J Ir Dent Assoc. 2000;46:3–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vallejo C, Iniesta P, Moraleda JM. Resolution of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia resistant to azithromycin by switching to tacrolimus. Haematologica. 2001;86:110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nowicki M, Kokot F, Wiecek A. Partial regression of advanced cyclosporin-induced gingival hyperplasia after treatment with azithromycin. A case report. Ann Transplant. 1998;3:25–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wahlstrom E, Zamora JU, Teichman S. Improvement in cyclosporine-associated gingival hyperplasia with azithromycin therapy. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:753–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503163321116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lafzi A, Farahani RM, Shoja MA. Phenobarbital-induced gingival hyperplasia. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2007;8:50–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sinha S, Kamath V, Arunodaya GR, Taly AB. Phenobarbitone induced gingival hyperplasia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:601. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gregoriou AP, Schneider PE, Shaw PR. Phenobarbital-induced gingival overgrowth? Report of two cases and complications in management. ASDC J Dent Child. 1996;63:408–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patil RB, Urs P, Kiran S, Bargale SD. Global developmental delay with sodium valproate-induced gingival hyperplasia. BMJ Case Rep 2014. 2014:pii: bcr2013200672. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-200672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Joshipura V. Sodium valproate induced gingival enlargement with pre-existing chronic periodontitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:278–81. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.99277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rodríguez-Vázquez M, Carrascosa-Romero MC, Pardal-Fernández JM, Iniesta I. Congenital gingival hyperplasia in a neonate with foetal valproate syndrome. Neuropediatrics. 2007;38:251–2. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tovaru S, Parlatescu I, Dumitriu AS, Bucur A, Kaplan I. Oral complications associated with D-penicillamine treatment for Wilson disease: A clinicopathologic report. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1231–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mistry S, Bhowmick D. Oral contraceptive pill induced periodontal endocrinopathies and its management: A case report. Eur J Dent. 2012;6:324–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Katz J, Givol N, Chaushu G, Taicher S, Shemer J. Vigabatrin-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:180–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Walker MR, Lovel SF, Melrose CA. Orthodontic treatment of a patient with a renal transplant and drug-induced gingival overgrowth: A case report. J Orthod. 2007;34:220–8. doi: 10.1179/146531207225022275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Khocht A, Schneider LC. Periodontal management of gingival overgrowth in the heart transplant patient: A case report. J Periodontol. 1997;68:1140–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.11.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jackson C, Babich S. Gingival hyperplasia: Interaction between cyclosporin A and nifedipine? A case report. N Y State Dent J. 1997;63:46–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Darbar UR, Hopper C, Speight PM, Newman HN. Combined treatment approach to gingival overgrowth due to drug therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:941–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dhingra K, Prakash S. Gingival overgrowth in partially edentulous ridges in an elderly female patient with epilepsy: A case report. Gerodontology. 2012;29:e1201–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2012.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.da Silveira EJ, Gordón-Núñez MA, Seabra FR, Bitu Filho RS, Lima EG, de Medeiros AM, et al. Peripheral calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor associated with generalized drug-induced gingival growth: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:341–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Priyadharshini V, Belure VV, Triveni MG, Tarun Kumar AB, Mehta DS. Successful management of phenytoin and phenobarbitone induced gingival enlargement: A multimodal approach. Contemp Clin Dent. 2014;5:268–71. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.132365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mattson JS, Blankenau R, Keene JJ. Case report. Use of an argon laser to treat drug-induced gingival overgrowth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:78–83. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Seymour RA, Thomason JM, Ellis JS. The pathogenesis of drug-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23(3 Pt 1):165–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb02072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim JY, Park SH, Cho KS, Kim HJ, Lee CK, Park KK, et al. Mechanism of azithromycin treatment on gingival overgrowth. J Dent Res. 2008;87:1075–9. doi: 10.1177/154405910808701110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Livada R, Shiloah J. Calcium channel blocker-induced gingival enlargement. J Hum Hypertens. 2014;28:10–4. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2013.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kimball OP. The treatment of epilepsy with sodium diphenyl hydantoinate. JAMA. 1939;112:1244–5. [Google Scholar]

- 97.McCord JF, Sloan P, Quayle AA, Hussey DJ. Phenytoin hyperplasia occurring under complete dentures: A clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;68:569–72. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(92)90366-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Seymour RE, Ellis JS, Thomason JM. Risk factors for drug-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:217–23. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027004217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mavrogiannis M, Ellis JS, Thomason JM, Seymour RA. The management of drug-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:434–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]