Abstract

Background:

Cytokines are significant in the development and progression of chronic periodontitis (ChP) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DT2). Insufficient information is available regarding the pro- versus anti-inflammatory cytokines in ChP's influence on systemic levels of cytokines on DT2. This study investigated the levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-6 in the serum of patients with ChP, DT2, and with both ChP and DT2, as compared to health.

Materials and Methods:

A total of eighty participants were grouped equally groups as healthy (NH), ChP with, and without DT2 (ChP and ChP + DT2) and only type 2 diabetes (DT2). Plaque and gingival indices, bleeding on probing, pocket probing depths, clinical attachment loss, were evaluated. Serum samples were collected to measure glycated hemoglobin, random blood sugar. TNF-α, IL-4 and -6 was assessed by ELISA.

Results:

The selected cytokines were detected in all the participants. TNF-α and IL-6 were highest in ChP + DT2 group, whereas IL-4 was highest in health. Significant differences and correlation were observed between the cytokines, periodontal, and glycemic parameters and among the four groups.

Conclusion:

TNF-α and IL-6 appear to heighten the inflammatory state in patients with both type 2 diabetes and periodontitis, but IL-4, though considered an anti-inflammatory mediator was not convincing in such a role in this study. The cytokine behavior needs to be studied further in larger studies.

Keywords: Cytokines, inflammation, interleukins, periodontitis, serum, type 2 diabetes mellitus

INTRODUCTION

Interactions involving plaque/dental biofilm and the host inflammatory reactions results in chronic periodontitis (ChP), which are driven by cytokines that may be pro- or anti-inflammatory.[1] Cytokines are proteins with pleiotropic actions which regulate inflammatory responses and function in networks.[2]

Cytokine actions are important in the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DT2)[3] which can accentuate insulin resistance, insulin deficiency, and diabetes.[3,4,5] The association of ChP and DT2 is known.[6] Periodontal disease can enhance insulin resistance and also chronic inflammation systemically, with sustained hyperglycemia.[7,8] ChP and DT2 have similar pathogenesis and may influence each other by showing related cytokine behavior and together can be considered as an awry immune response.[9,10]

One of the widely investigated cytokines is tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, an important pro-inflammatory mediator associated with ChP and DT2.[11,12,13,14] Interleukin (IL)-6 is a cytokine having arguably pleiotropic activities, which may be destructive or protective.[15,16] Higher expression of periodontal IL-6 has been observed in individuals having both ChP and DT2 compared with patients with ChP alone or without both diseases.[17] IL-4 decreases the secretion of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, and thus may be anti-inflammatory.[18,19,20] IL-4 is implicated in the DT2 pathogenesis.[21] Hence, this study had the objective of investigating whether ChP intensifies systemic inflammation associated with DT2 by evaluating the serum levels of the cytokines, namely, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-4 in healthy individuals, ChP patients (who have no systemic diseases/conditions), and in DT2 patients with/without ChP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The sample population recruited was healthy individuals and patients who visited the outpatient departments of this institution as well as the concerned medical hospital. This research proposal obtained the required ethical clearance from the ethical committee of this institution (Reference No: 2013/S/PERIO/15) complying with the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki. A total of eighty gender-matched participants between 30 to 55 years were enrolled, after obtaining their written informed consent. In this study, ChP was diagnosed by assessing (apart from patient's history), the periodontal parameters which included pocket probing depth (PPD) of more than or equal to 5 mm, generalized bleeding on probing (BoP) and generalized clinical attachment loss (CAL) of more than or equal to 2 mm with alveolar bone loss visualized by radiographs. DT2 was previously diagnosed by the concerned physician/specialist based on the criteria of the American Diabetes Association.[22,23] Patients with at least 1 year history of DT2 who were diagnosed with the condition having glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) between 7.5% and 9.5%, with random/casual blood glucose/sugar (RBS) more than 200 mg/dl, having no history or current complications associated with diabetes were included. Such DT2 patients were on physician prescribed diabetes medication/treatment with no changes in therapy for at least a period of the previous 12 months. Only those individuals with body mass index of <30 and lipid profiles in acceptable range/values were involved. Individuals who smoked and/or chewed tobacco, or those who had periodontal treatment in the previous 90 days, or those with systemic disorders/diseases (with the exception of DT2 as per our inclusion criteria), bleeding disorders/tendencies due to any medical reason, pregnant or nursing mothers, patients who were immunosuppressed, individuals who required antibiotics as prophylactics before or during dental therapy, or those who were on any medication just before the study, were all excluded from this study. Recording of the dental/medical history and periodontal examination was performed on the participants by one examiner (ABA). The plaque index (PlI)[24] was recorded along with the gingival index (GI).[25] Measurements for BoP, pockets, and CAL were noted. Prescribed radiographs were used to assess the loss of supporting alveolar bone. HbA1C and RBS levels were estimated in the concerned hematology laboratory. The subjects who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were grouped as: Systemically normal and periodontally healthy group (NH) (n = 20); ChP group (n = 20); ChP with type 2 diabetes group (ChP + DT2) (n = 20), and type 2 diabetes without ChP group (DT2) (n = 20). Serum was obtained from the samples of blood collected from the subjects. An HbA1C test kit (Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway) was used to evaluate HbA1C levels. Kinetic method: Infinite STAT Glucose (Accurex Biomedicals Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, India) was used to estimate RBS TNF-α, ILs-4, and -6 was measured using ELISA (Krishgen BioSystems, Mumbai, India).

Statistical analyses

The raw data for statistical analyses were tabulated and means and standard deviations calculated. To test the normality of the variables, Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were first done. The four groups were compared group-wise/pair-wise using nonparametric tests, i.e., Mann–Whitney U-test, Kruskall–Wallis, and Wilcoxon Sign Rank tests for those variables which were not following a normal distribution. Karl Pearson's test was employed for correlation analyses. A step-wise regression analysis was also performed. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) computed the analyses.

RESULTS

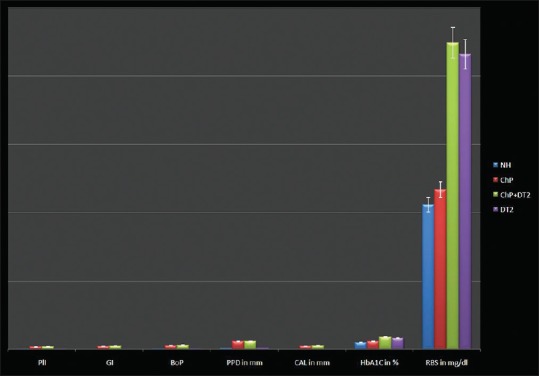

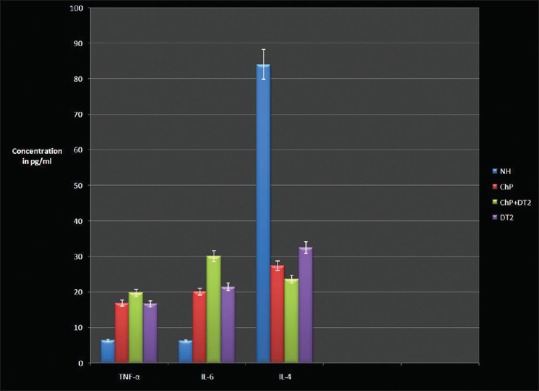

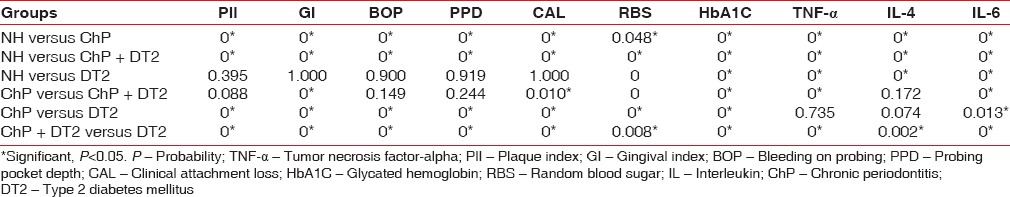

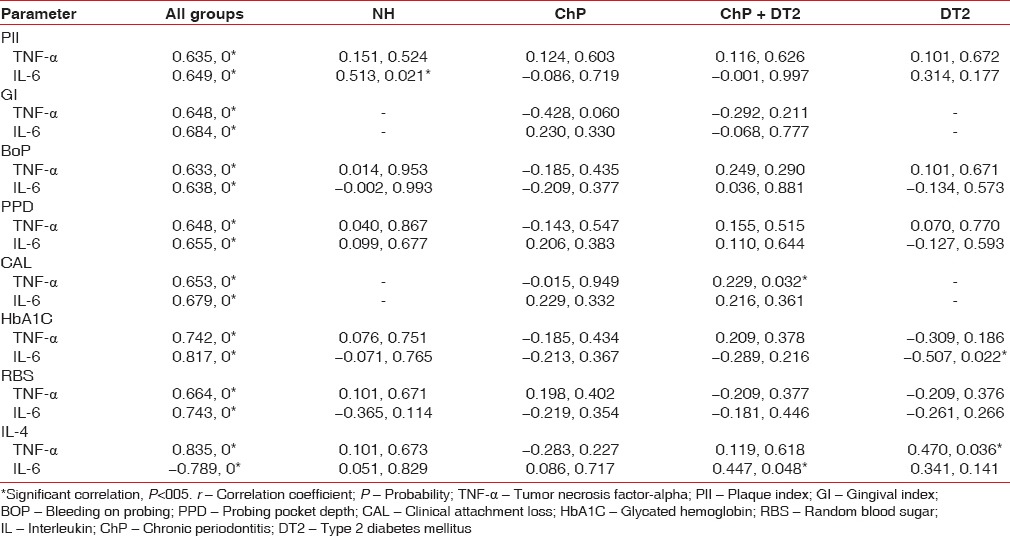

The four groups with a total of eighty age and gender-matched subjects expressed the cytokines of interest to this study. Serum TNF-α (lowest 3.29 pg/ml, highest 22.14 pg/ml), IL-6 (lowest 4.24 pg/ml, highest 35.21 pg/ml), and IL-4 (lowest 15.32 pg/ml, highest 119.12 pg/ml) was detected in all the participants and is presented as a graphical representation along with PlI, GI, BoP, PPD, CAL, HbA1C, and RBS [Figures 1 and 2]. Mann–Whitney (U-test) and Wilcoxon Sign Rank (W) tests returned significant statistical differences as depicted in Table 1. IL-4 did not differ when ChP was compared with ChP + DT2. TNF-α and IL-4 did not differ when ChP was compared with DT2. When all the groups were combined and analyzed, the cytokines correlated significantly with the periodontal clinical parameters and the glycemic variables. No statistically significant correlations were noted in each group, except for TNF-α with CAL in the ChP + DT2 group; HbA1C with IL-6, and also TNF-α with IL-4 in the DT2 group. Table 2 presents the periodontal clinical, glycemic variables including IL-4 and their correlations with TNF-α and IL-6. The step-wise regression analysis did not return significant results.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of mean ± standard deviation of PlI, GI, BoP, PPD, CAL, HbA1C, RBS in the four groups. PlI – Plaque index; GI – Gingival index; BoP – Bleeding on probing; PPD – Probing pocket depth; CAL – Clinical attachment loss; HbA1C – Glycated hemoglobin; RBS – Random blood sugar

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of mean ± standard deviation of TNF-α, interleukin-4 and -6 in the four groups. TNF-α – Tumor necrosis factor-α; IL – Interleukin

Table 1.

Consolidated pair wise comparisons showing the P value between the four groups for plaque index, gingival index, bleeding on probing, probing pocket depth, clinical attachment loss, glycated hemoglobin, random blood sugar, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-4 and interleukin-6 using Mann-Whitney U-test and Wilcoxon sign rank W-test

Table 2.

Karl Pearson's correlation analysis (r, P) between plaque index, gingival index, bleeding on probing, probing pocket depth, clinical attachment loss, glycated hemoglobin, random blood sugar, interleukin-4 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6 in the four groups

DISCUSSION

ChP as a local infection can possibly disseminate into the systemic circulation thereby accentuating the inflammatory condition in disorders such as DT2.[26]

DT2 patients in our study had moderately/poorly controlled hyperglycemia with the lipid profile in acceptable limits. Among the clinical and glycemic variables, we found significant differences in the GI, CAL, HbA1C, and RBS between ChP and ChP + DT2 patients and for all the clinical and glycemic variables between ChP and DT2 patients, and between ChP + DT2 and DT2 patients.

TNF-α and IL-6 were found to be elevated in the diseased groups which is in agreement with other reports.[27,28] Another investigation[29] mentions no significant correlation between clinical periodontal variables and TNF-α which we could also confirm in our study, but CAL and TNF-α correlated positively in the ChP + DT2 group. TNF-α is related to ChP in DT2.[30] Our study revealed a contrary association between HbA1C and IL-6 in the DT2 group. Hence, IL-6 need not be higher in diabetes, probably because IL-6 is a pleuripotent cytokine having anti-inflammatory effects.[31]

It is traditionally accepted that IL-4 has anti-inflammatory functions, but may have multiple actions.[20] IL-4 did not differ significantly between ChP and DT2. Lower levels of IL-4 was observed in ChP + DT2 which is similar to another study,[32] although IL-4 and TNF-α in our investigation correlated positively with each other in DT2. Hence, a conclusive anti-inflammatory role for IL-4 is not forthcoming. However, both TNF-α, IL-6 indicate a strong pro-inflammatory role in ChP and DT2. TNF-α is elevated in diabetics which has been observed in our data.[11,33,34] IL-6 is increased in ChP,[35] and enhances alveolar bone destruction. Conversely, IL-6 also induces IL-1 receptor antagonist,[31] protecting overt inflammatory responses, and influences vascular homeostasis.[36] Cytokines, therefore, have a complex functionality. A balance between cytokines which appear to promote inflammation (IL-6, TNF-α), and cytokines which seemingly control inflammation (IL-4), is necessary in disease development and progression, particularly in the context of ChP and DT2 manifesting together.[37,38] The nature of cytokine responses is multifaceted, and it is not easy to ascribe specific and constant roles for each of the various cytokines which undoubtedly function in complex networks, especially when two diseases, such as a ChP and DT2 occur concurrently.

One limitation of this study is that the measured cytokine values may not be truly reflected because all the diabetes patients were diagnosed at least 1 year before being recruited for the current investigation. Hence, the HbA1C and RBS values selected by our study method were to try and understand the quantitative cytokine behavior in these predetermined conditions. Another limitation is that we did not attempt to delineate the individual patients with diabetes as well-controlled, or moderately, or poorly controlled hyperglycemia, which possibly would have required additional groups of specified participants for such a study. In addition, all the diabetes patients were being treated for the condition with drugs such as metformin, or insulin. These medications may exert an anti-inflammatory effect, although it is not conclusive according to the literature.[39,40,41] This again, adds another issue, i.e., changing or ceasing the medications, to observe the nature of the cytokines and their interactions, which would be unacceptable due to ethical reasons. Therefore, the evaluation was performed with the stated inclusion and exclusion criteria. Moreover, a question might arise as to why other cytokines were not assessed. Considering the large number of cytokines, it was not feasible to evaluate more.

CONCLUSION

This study indicates that the inflammatory status in DT2 is enhanced by ChP due to higher expression of TNF-α and IL-6 indicating accentuated inflammation, but there are variations in the functions of IL-4. Larger studies are required to understand the destructive and protective behavior and interactions of such biological mediators in periodontal diseases and diabetes.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tatakis DN, Kumar PS. Etiology and pathogenesis of periodontal diseases. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:491–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.03.001. v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preshaw PM, Taylor JJ. How has research into cytokine interactions and their role in driving immune responses impacted our understanding of periodontitis? J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(Suppl 11):60–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickup JC, Crook MA. Is type II diabetes mellitus a disease of the innate immune system? Diabetologia. 1998;41:1241–8. doi: 10.1007/s001250051058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:98–107. doi: 10.1038/nri2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernández-Real JM, Pickup JC. Innate immunity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2012;55:273–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2387-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapple IL, Genco R Working Group of Joint EFP/AAP Workshop. Diabetes and periodontal diseases: Consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on periodontitis and systemic diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(Suppl 14):S106–12. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loos BG. Systemic markers of inflammation in periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2005;76(11 Suppl):2106–15. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genco RJ, Grossi SG, Ho A, Nishimura F, Murayama Y. A proposed model linking inflammation to obesity, diabetes, and periodontal infections. J Periodontol. 2005;76(11 Suppl):2075–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thunell DH, Tymkiw KD, Johnson GK, Joly S, Burnell KK, Cavanaugh JE, et al. A multiplex immunoassay demonstrates reductions in gingival crevicular fluid cytokines following initial periodontal therapy. J Periodontal Res. 2010;45:148–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2009.01204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iacopino AM. Periodontitis and diabetes interrelationships: Role of inflammation. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:125–37. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graves DT, Cochran D. The contribution of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor to periodontal tissue destruction. J Periodontol. 2003;74:391–401. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mishima Y, Kuyama A, Tada A, Takahashi K, Ishioka T, Kibata M. Relationship between serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha and insulin resistance in obese men with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2001;52:119–23. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King GL. The role of inflammatory cytokines in diabetes and its complications. J Periodontol. 2008;79(8 Suppl):1527–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernández-Real JM, Ricart W. Insulin resistance and chronic cardiovascular inflammatory syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:278–301. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akira S, Taga T, Kishimoto T. Interleukin-6 in biology and medicine. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:1–78. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohamed-Ali V, Goodrick S, Rawesh A, Katz DR, Miles JM, Yudkin JS, et al. Subcutaneous adipose tissue releases interleukin-6, but not tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in vivo . J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:4196–200. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross JH, Hardy DC, Schuyler CA, Slate EH, Mize TW, Huang Y. Expression of periodontal interleukin-6 protein is increased across patients with neither periodontal disease nor diabetes, patients with periodontal disease alone and patients with both diseases. J Periodontal Res. 2010;45:688–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2010.01286.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai CC, Ku CH, Ho YP, Ho KY, Wu YM, Hung CC. Changes in gingival crevicular fluid interleukin-4 and interferon-gamma in patients with chronic periodontitis before and after periodontal initial therapy. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2007;23:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. Heterogeneity of cytokine secretion patterns and functions of helper T cells. Adv Immunol. 1989;46:111–47. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60652-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.te Velde AA, Huijbens RJ, Heije K, de Vries JE, Figdor CG. Interleukin-4 (IL-4) inhibits secretion of IL-1 beta, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-6 by human monocytes. Blood. 1990;76:1392–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bid HK, Konwar R, Agrawal CG, Banerjee M. Association of IL-4 and IL-1RN (receptor antagonist) gene variants and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A study in the north Indian population. Indian J Med Sci. 2008;62:259–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 1):S11–66. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2015 abridged for primary care providers. Clin Diabetes. 2015;33:97–111. doi: 10.2337/diaclin.33.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Dyke TE, van Winkelhoff AJ. Infection and inflammatory mechanisms. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(Suppl 14):S1–7. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amar S, Han X. The impact of periodontal infection on systemic diseases. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9:RA291–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor GW, Burt BA, Becker MP, Genco RJ, Shlossman M, Knowler WC, et al. Severe periodontitis and risk for poor glycemic control in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol. 1996;67(10 Suppl):1085–93. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saxlin T, Suominen-Taipale L, Leiviskä J, Jula A, Knuuttila M, Ylöstalo P. Role of serum cytokines tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 in the association between body weight and periodontal infection. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:100–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engebretson S, Chertog R, Nichols A, Hey-Hadavi J, Celenti R, Grbic J. Plasma levels of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in patients with chronic periodontitis and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tilg H, Trehu E, Atkins MB, Dinarello CA, Mier JW. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) as an anti-inflammatory cytokine: Induction of circulating IL-1 receptor antagonist and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor p55. Blood. 1994;83:113–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ribeiro FV, de Mendonça AC, Santos VR, Bastos MF, Figueiredo LC, Duarte PM. Cytokines and bone-related factors in systemically healthy patients with chronic periodontitis and patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1187–96. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.100643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desfaits AC, Serri O, Renier G. Normalization of plasma lipid peroxides, monocyte adhesion, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in NIDDM patients after gliclazide treatment. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:487–93. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nilsson J, Jovinge S, Niemann A, Reneland R, Lithell H. Relation between plasma tumor necrosis factor-alpha and insulin sensitivity in elderly men with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1199–202. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.8.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Irwin CR, Myrillas TT. The role of IL-6 in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Oral Dis. 1998;4:43–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1998.tb00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lau DC, Dhillon B, Yan H, Szmitko PE, Verma S. Adipokines: Molecular links between obesity and atheroslcerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2031–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01058.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Preshaw PM, Foster N, Taylor JJ. Cross-susceptibility between periodontal disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: An immunobiological perspective. Periodontol 2000. 2007;45:138–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2007.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor JJ, Preshaw PM, Lalla E. A review of the evidence for pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontitis and diabetes. J Periodontol. 2013;84(4 Suppl):S113–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.134005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saisho Y. Metformin and inflammation: Its potential beyond glucose-lowering effect. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2015;15:196–205. doi: 10.2174/1871530315666150316124019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheen AJ, Esser N, Paquot N. Antidiabetic agents: Potential anti-inflammatory activity beyond glucose control. Diabetes Metab. 2015;41:183–94. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kothari V, Galdo JA, Mathews ST. Hypoglycemic agents and potential anti-inflammatory activity. J Inflamm Res. 2016;9:27–38. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S86917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]