Abstract

Background:

It is widely accepted that there are socioeconomic inequalities in oral health. A socioeconomic gradient is found in a range of clinical and self-reported oral health outcomes.

Aim:

The present study was conducted to assess the differences in oral hygiene practices among patients from different socioeconomic status (SES) visiting the Outpatient Department of the Sudha Rustagi College of Dental Sciences.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted from June to October 2014 to assess the effect of SES on the oral hygiene habits. The questionnaire included the questions related to the demographic profile and assessment of the oral hygiene habits of the study population.

Results:

Toothbrush and toothpaste were being used significantly (P < 0.05) more by lower middle class (84.4%) and upper middle class (100.0%). A significantly higher frequency of cleaning teeth (twice a day) was reported among the lower middle class (17.2%) and upper middle class (21.5%). The majority (34.3%) of the study population changed their toothbrush once in 3 months. The cleaning of tongue was reported by patients belonging to the upper middle (62.0%), lower middle (52.1%), and upper lower class (30.0%). The use of tongue cleaner was reported to be significantly (P < 0.05) more among upper middle (10.1%) class patients. A significantly higher number of patients from the lower class (81.3%) never visited a dentist.

Conclusion:

The oral hygiene practices of the patients from upper and lower middle class was found to be satisfactory whereas it was poor among patients belonging to lower and upper lower class.

Keywords: Oral health, oral hygiene, toothpaste

INTRODUCTION

Health is multifactorial, influenced by factors such as genetics, lifestyle, environment, socioeconomic status (SES), and many others.[1] Health cannot be isolated from its social context and the last few decades have witnessed that social and economic factors have as much influence on health as the medical interventions.[1]

Over the last century, health has improved significantly. This improvement, however, has not been experienced equally across the population, being considerably greater among the better off.[2] High economic status alone cannot contribute to better health.[1] Although it is a major factor for improving the health,[3,4,5,6] it can be a contributing factor for illness as well, like in the occurrence of coronary heart disease, diabetes, and obesity.[1] Studies indicate that education to some extent compensates the effect of poverty on health. Kerala with its high literacy status has better health (low infant mortality rate) compared to other parts of India, in spite of having lesser per capita income than the national average.[1]

Oral health is always an inseparable part of general health and several studies in the past have revealed an association between socioeconomic factors and oral health.[3,4,5,6,7] The need and demand for clear scientific evidence to inform and support the oral health policy-making process is greater than ever. Studies have shown that over the last decade, the differences in the oral health status between the individuals with a high SES and those with a low SES had markedly increased.[8]

Various studies[9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] in the past have suggested an association between neighborhood characteristics and self-rated general health. The individuals living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to rate their general health as poor than their counterparts living in more advantaged neighborhoods, regardless of their SES. Despite the existing evidence for the association between self-rated health status and neighborhood characteristics, to date, no study has explored a similar association for self-rated oral health in the US. However, in Canada, Locker and Ford[21,22] found that individuals living in low-income areas were more likely to rate their oral health as fair or poor than those living in high-income areas.

There is consistent evidence throughout Europe that people at a socioeconomic disadvantage suffer a heavier burden of oral health problems than their better-off counterparts.[23] These socioeconomic inequalities in oral health are a major challenge for health policy, not only because most of the inequalities can be considered unfair but also because reducing the burden of oral health problems in disadvantaged groups offers great potential for improving the average oral health status of the population as a whole.[24]

It is widely accepted that there are socioeconomic inequalities in oral health.[25,26] A socioeconomic gradient is found in a range of clinical and self-reported oral health outcomes.[27,28,29,30] A growing body of empirical research,[31] together with theoretical modeling of the social determinants of oral health,[32] suggests that the socioeconomic gradient in oral health may be related to social, environmental, and political factors, which act through material, behavioral, and psychosocial pathways.

Sheiham and Watt[33] state that: “The main causes of inequalities (in oral health) are differences in patterns of consumption of nonmilk extrinsic sugars and fluoridated toothpaste. Improvements in oral health that have occurred over the last 30 years have been largely a result of fluoride toothpaste and social, economic and environmental factors. Oral health inequalities will only be reduced through the implementation of effective and appropriate oral health promotion policy. Treatment services will never successfully tackle the underlying cause of oral disease.”

All these disparities in part can be attributed to the differences in oral hygiene practices among the different socioeconomic groups. Thus, the present study was conducted to assess the differences in oral hygiene practices among patients from different SES visiting the outpatient department (OPD) of the Sudha Rustagi College of Dental Sciences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional survey was done to assess the effect of SES on the oral hygiene habits. The survey was conducted from June to October 2014. The questionnaire included the questions related to the demographic profile and assessment of the oral hygiene habits of the study population.

The questionnaire included information related to the patient's name, age, gender, occupation, and residential area. The oral hygiene habits of the study population were assessed including the use of oral hygiene aid, frequency of cleaning teeth, duration of cleaning teeth, frequency of changing toothbrush, rinsing of mouth with water, use of mouthwash, and tongue cleaning aid used.

The SES of the population was assessed using the Kuppuswamy scale[34] which is based on per capita income per month, education status, and occupational status of the study population.

Inclusion criteria

Systemically healthy individuals aged above 18 years of age

The patients willing to give informed consent were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with history of systemic disease (debilitating disease or any condition having a substantial effect on oral health)

Pregnancy and lactation

Undergone oral prophylaxis during the past 6 months.

Ethical clearance

The ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Sudha Rustagi College of Dental Sciences, Faridabad. Informed consent was obtained from the patients who participated in the study.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 21.0 software (IBM Inc., Chicago, USA). Descriptive statistics (number and percentage of responses for the questions related to the oral hygiene practices including the demographic information) were calculated for response items. Chi-square test was applied for comparison of oral hygiene practices among patients belonging to different SES. Multinomial regression analysis was done for the odds ratio (OR) for the relationship of SES with the oral hygiene habits.

RESULTS

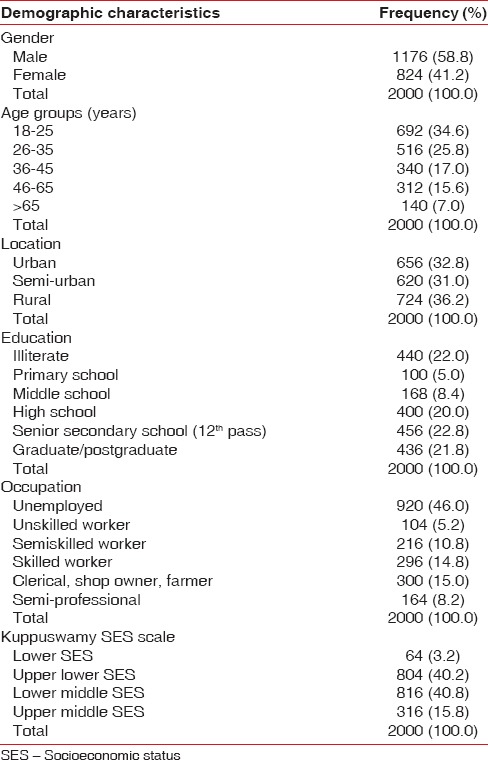

The mean age of the study population was 35.32 ± 15.529 (range 18–80) years. The study population included 1176 (58.8%) males and 824 (41.2%) females. The majority of the patients belonged from the rural areas (36.2%), followed by urban areas (32.8%) and semi-urban areas (31.0%) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population

The study population comprised 64 (3.2%) patients belonging to lower class, 852 (42.6%) belonging to upper lower class, 768 (38.4%) belonging to lower middle class, and 316 (15.8%) patients belonging to upper middle class [Table 1].

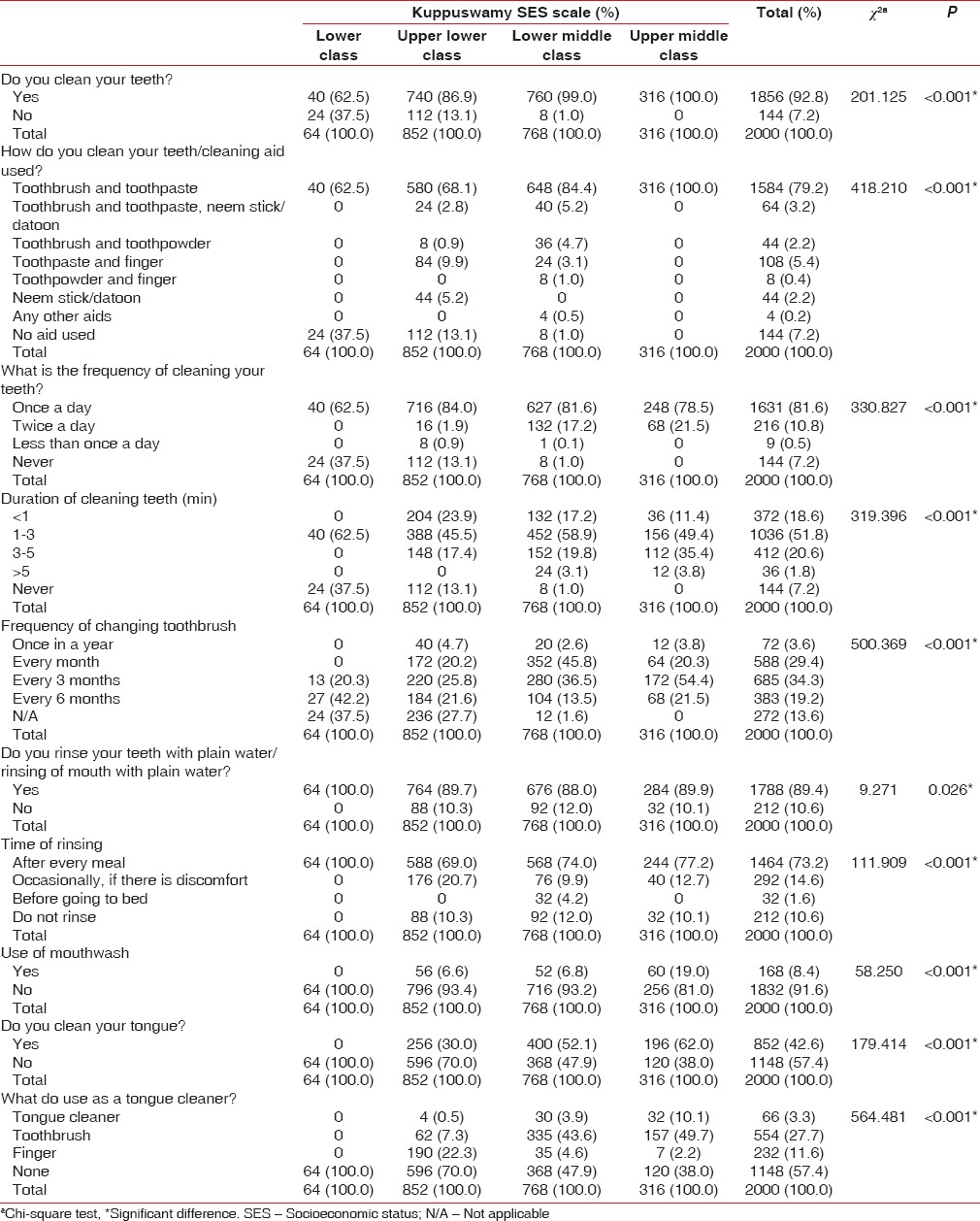

There was a significant association between the Kuppuswamy SES scale and cleaning of teeth. The cleaning of teeth being performed significantly (P < 0.05) more by lower middle class (99.0%) and upper middle class (100.0%) in comparison to the lower class and upper lower class [Table 2].

Table 2.

Oral hygiene practices among the study population

Toothbrush and toothpaste were being used significantly (P < 0.05) more by lower middle class (84.4%) and upper middle class (100.0%) in comparison to the lower class and upper lower class. The use of neem stick/datoon was reported by the patients belonging to upper lower class only (5.2%). The use of no cleaning aids for personal oral hygiene was reported to be significantly more among the patients belonging to lower class (37.5%) and upper lower class (13.1%) [Table 2].

A significant association was reported between the Kuppuswamy SES scale and frequency of cleaning the teeth. A significantly higher frequency of cleaning teeth (twice a day) was reported among the lower middle class (17.2%) and upper middle class (21.5%) in comparison to the lower class (0%) and upper lower class (1.9%) [Table 2].

There was a significant (P < 0.05) relationship between the Kuppuswamy scale and duration of cleaning the teeth. The performing of oral hygiene for 3–5 min and more than 5 min was reported to be significantly more among the patients belonging to lower middle class (19.8% and 3.1%, respectively) and upper middle class (35.4% and 3.8%, respectively) [Table 2].

There was a significant (P < 0.05) relationship between the Kuppuswamy scale and frequency of changing the toothbrush. The majority of the study population changed their toothbrush once in 3 months (n = 685, 34.3%), followed by every month (n = 588, 29.4%). Significantly (P < 0.05) more number of patients from the lower middle class (45.8% and 36.5%, respectively) and upper middle class (20.3% and 54.4%, respectively) changed their toothbrush once every 3 months and once in a month whereas significantly (P < 0.05) more number of patients from the lower class (42.2%) and upper lower class (21.6%) changed their toothbrush once every 6 months [Table 2].

The majority (1788, 89.4%) of the study population rinsed their mouth with plain water after meal. The rinsing of mouth with water after meal was found to be significantly more among lower class patients (100%) in comparison to the patients from other socioeconomic classes [Table 2].

The use of mouthwash was reported by patients belonging to upper middle class (19.0%), lower middle class (6.6%), and higher lower class (6.8%). There was a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) among the patients from different SES [Table 2].

A statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) was seen in the cleaning of tongue. The cleaning of tongue was reported by patients belonging to the upper middle (62.0%), lower middle class (52.1%), and upper lower class (30.0%) whereas none of the patients from the lower class reported cleaning of the tongue. The use of tongue cleaner was reported to be significantly (P < 0.05) more among upper middle (10.1%) class patients whereas toothbrush was used for tongue cleaning more by upper middle (49.7%) and lower middle (43.6%) class patients. Most of the patients (22.3%) from the upper lower class used finger for tongue cleaning [Table 2].

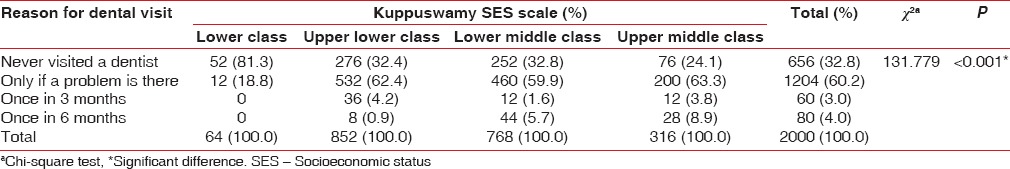

The majority (n = 1204, 60.2%) of the patients in the present study reported visiting a dentist only if a problem was there. A significantly higher number of patients from the lower class (81.3%) never visited a dentist and were visiting for the first time. A significantly higher number of patients from the lower middle (5.7%) and upper middle (8.9%) class visited a dentist once every 6 months [Table 3].

Table 3.

Reason for dental visit among the study population

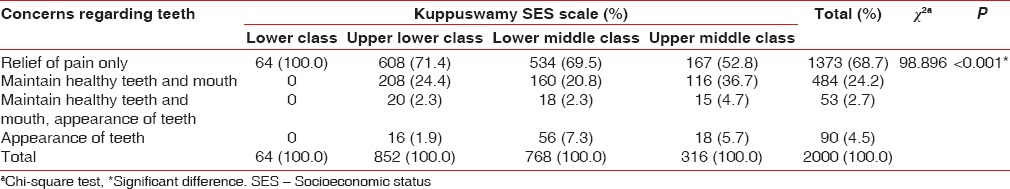

The majority (n = 1373, 68.7%) of the patients in the present study were concerned about relief of pain only. All the patients (100%) from lower class were only concerned about relief of pain only whereas a significantly higher proportion of patients from the lower middle (20.8%) and upper middle class (36.7%) were concerned about the maintenance of healthy teeth and mouth. The patients from the lower middle (7.3%) and upper middle class (5.7%) were also concerned about the appearance of their teeth [Table 4].

Table 4.

Concerns regarding teeth among the study population

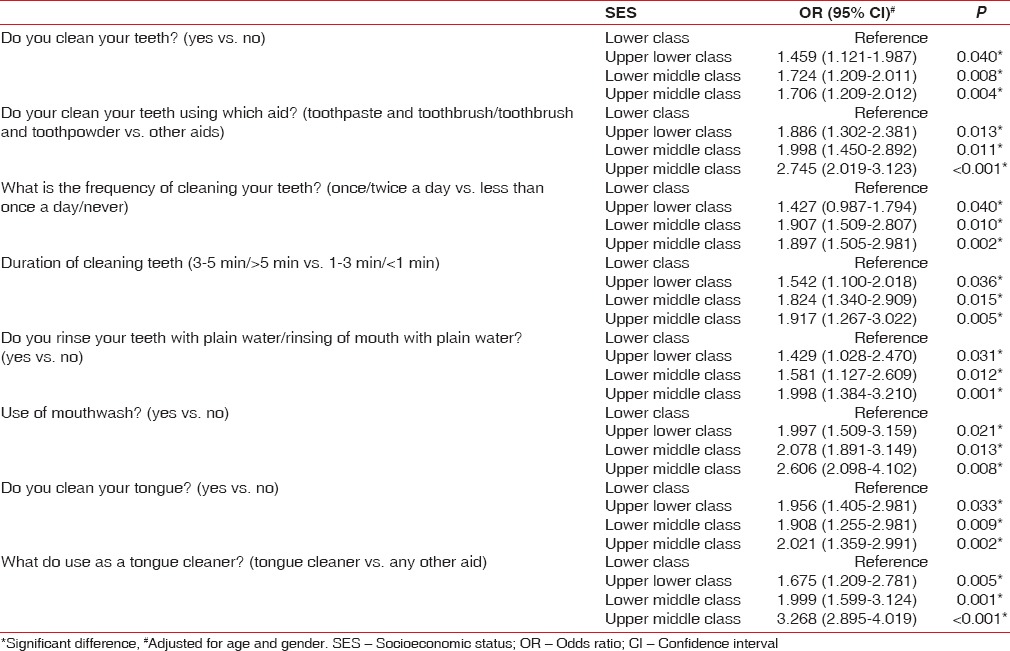

Multinomial regression analysis was done to estimate the OR taking age and gender as covariates. It was seen that with the improvement in SES, there was an improvement in the oral hygiene habits. It was seen that the patients of lower middle class and upper middle class had better chances of cleaning teeth (OR [95% confidence interval (CI)] = 1.724 [1.209–2.011] and 1.706 [1.209–2.012], respectively), using toothpaste and toothbrush (OR [95% CI] = 1.998 [1.450–2.892] and 2.745 [2.019–3.123], respectively), cleaning teeth once/twice a day (OR [95% CI] = 1.907 [1.509–2.807] and 1.897 [1.505–2.981], respectively), cleaning teeth for 3–5 min/more than 5 min (OR [95% CI] = 1.824 [1.340–2.909] and 1.917 [1.267–3.022], respectively), rinsing of mouth with plain water (OR [95% CI] = 1.581 [1.127–2.609] and 1.998 [1.384–3.210], respectively), mouthwash use (OR [95% CI] = 2.078 [1.891–3.149] and 2.606 [2.098–4.102], respectively), cleaning of tongue (OR [95% CI] = 1.908 [1.255–2.981] and 2.021 [1.359–2.991], respectively) and use of a tongue cleaner (OR [95% CI] = 1.999 [1.599–3.124] and 3.268 [2.895–4.019], respectively) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Multinomial regression model showing the comparison of the oral hygiene habits with respect to oral hygiene habits

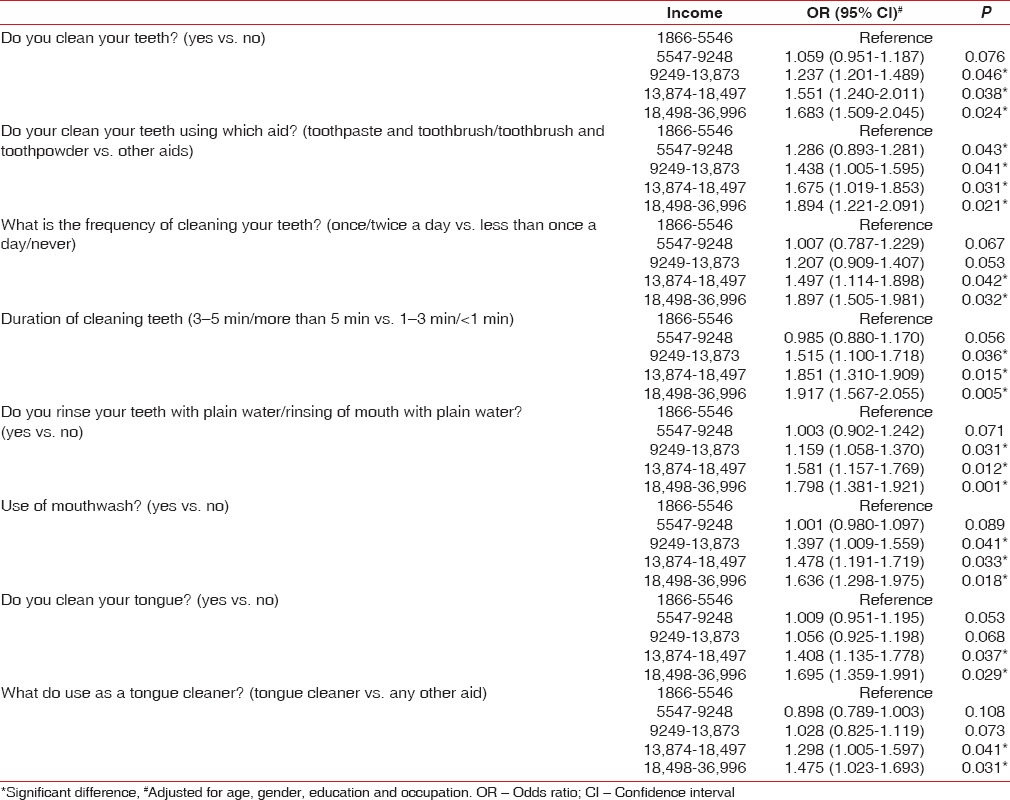

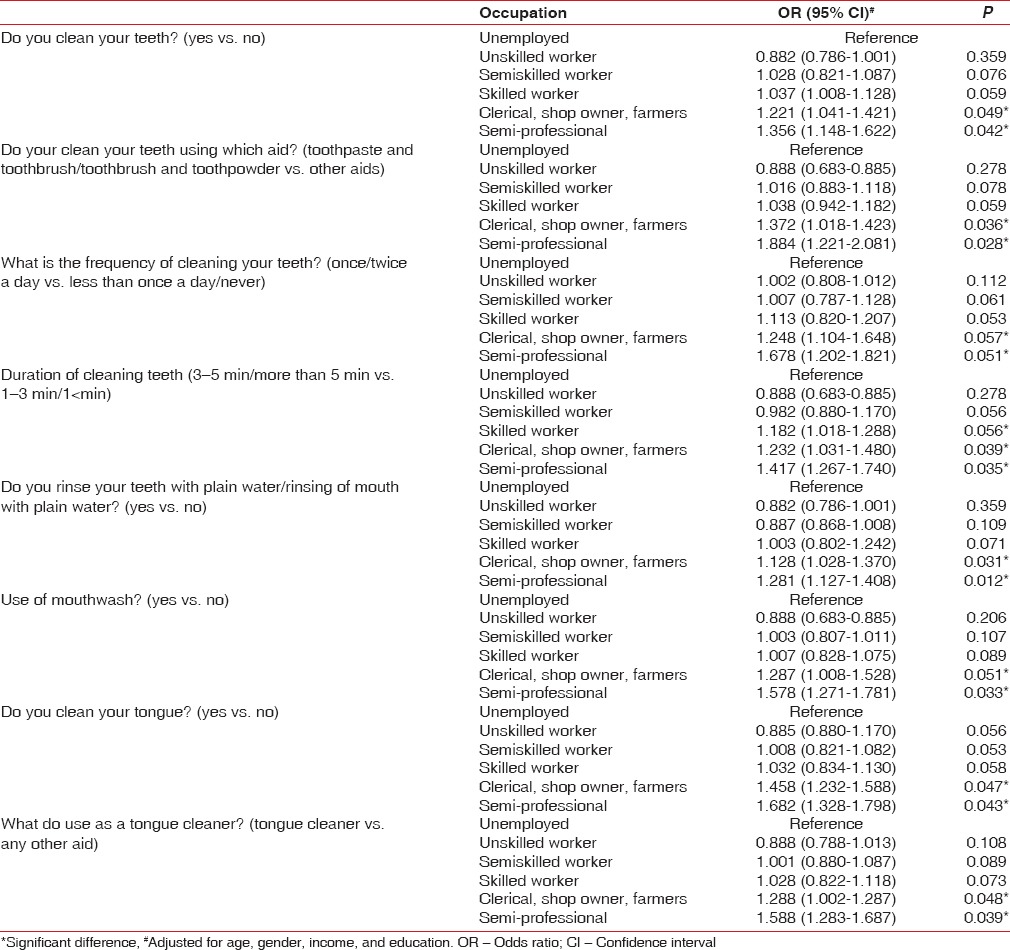

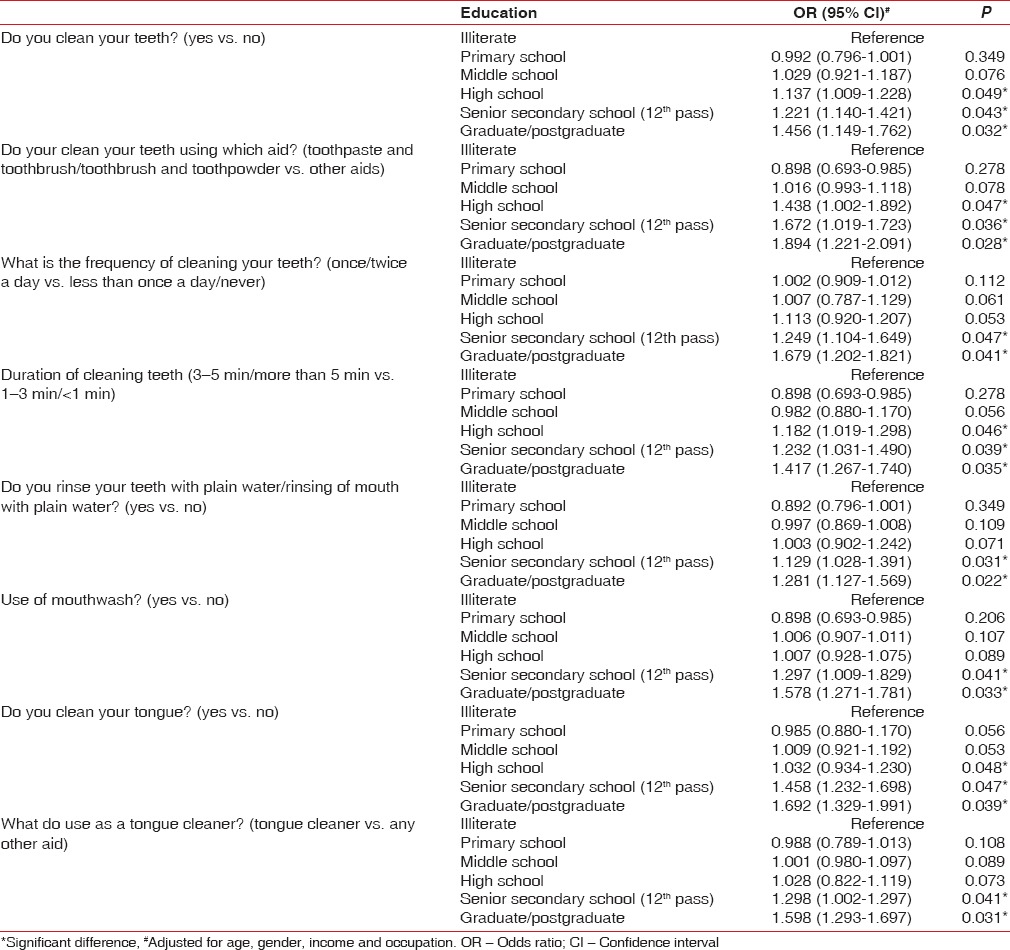

Multinomial regression analysis was done to estimate the OR for income, education, and occupation controlling for age, gender, income, education, and occupation, respectively [Tables 6-8]. The OR showed that the income, education, and occupation had a substantial effect on the oral hygiene habits of the study population. Better chances of cleaning teeth was seen among patients in income categories 9249–13,873, 13,874–18,497, and 18,498–36,996 (OR [95% CI] = 1.237 [1.201–1.489], 1.551 [1.240–2.011], and 1.683 [1.509–2.045], respectively), patients with high school, senior secondary school (12th pass), and graduate/postgraduate education (OR [95% CI] = 1.221 [1.140–1.421], 1.456 [1.149–1.762], and 1.456 [1.149–1.762], respectively) and clerical, shop owner, farmers (OR [95% CI] = 1.221 [1.041–1.421]) and semi-professional (OR [95% CI] = 1.356 [1.148–1.622]).

Table 6.

Multinomial regression model showing the comparison of the oral hygiene habits with respect to oral hygiene habits

Table 8.

Multinomial regression model showing the comparison of the oral hygiene habits with respect to oral hygiene habits

Table 7.

Multinomial regression model showing the comparison of the oral hygiene habits with respect to oral hygiene habits

Use of toothpaste and toothbrush/toothbrush and toothpowder as a cleaning aid was found to be more among patients in income categories 5547–9248, 9249–13,873, 13,874–18,497, and 18,498–36,996 (OR [95% CI] = 1.286 [0.893–1.281], 1.438 [1.005–1.595], 1.675 [1.019–1.853] and 1.894 [1.221–2.091]), patients with high school, senior secondary school (12th pass) and graduate/postgraduate education (OR [95% CI] = 1.438 [1.002–1.892], 1.672 [1.019–1.723] and 1.894 [1.221–2.091], respectively) and clerical, shop owner, farmers (OR [95% CI] = 1.372 [1.018–1.423]) and semi-professional (OR [95% CI] = 1.884 [1.221–2.081]).

Cleaning teeth once/twice a day was found to be significantly better among patients belonging to income categories 13,874–18,497 and 18,498–36,996 (OR [95% CI] = 1.497 [1.114–1.898] and 1.897 [1.505–1.981], respectively), patients with high school and graduate/postgraduate education (OR [95% CI] = 1.249 [1.104–1.649] and 1.679 [1.202–1.821], respectively). Cleaning of teeth for 3–5 min/more than 5 min was significantly more among patients belonging to income categories 9249–13,873, 13,874–18,497, and 18,498–36,996 (OR [95% CI] = 1.515 [1.100–1.718], 1.851 [1.310–1.909] and 1.917 [1.567–2.055], respectively), patients with high school and graduate/postgraduate education (OR [95% CI] = 1.232 [1.031–1.490] and 1.417 [1.267–1.740], respectively) and clerical, shop owner, farmers (OR [95% CI] = 1.232 [1.031–1.480]) and semi-professional (OR [95% CI] = 1.417 [1.267–1.740]).

Mouthwash use was reported among patients with 13,874–18,497 and 18,498–36,996 (OR [95% CI] = 1.478 [1.191–1.719] and 1.636 [1.298–1.975], respectively), patients with high school and graduate/postgraduate education (OR [95% CI] = 1.297 [1.009–1.429] and 1.578 [1.271–1.781], respectively) and semi-professional (1.578 [1.271–1.781]). Tongue cleaning was reported among patients with income categories 13,874–18,497 and 18,498–36,996 (OR [95% CI] = 1.408 [1.135–1.778] and 1.695 [1.359–1.991], respectively), patients with high school and graduate/postgraduate education (OR [95% CI] = 1.458 [1.232–1.698] and 1.692 [1.329–1.991], respectively), farmers (OR [95% CI] = 1.458 [1.232–1.588]) and semi-professional (OR [95% CI] = 1.682 [1.328–1.798]). Use of a tongue cleaner was reported to be significantly more among patients with income categories 13,874–18,497 and 18,498–36,996 (OR [95% CI] = 1.298 [1.005–1.597] and 1.475 [1.023–1.693], respectively), patients with high school and graduate/postgraduate education (OR [95% CI] = 1.298 [1.002–1.297] and 1.598 [1.293–1.697], respectively) and clerical, shop owner, farmers (OR [95% CI] = 1.288 [1.002–1.287]) and semi-professional (OR [95% CI] = 1.588 [1.283–1.687]).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, a large proportion (92.8%) of the study population was cleaning their teeth on a routine basis. Oral hygiene practices in India are deeply based in tradition and culture with use of indigenous substances being widely prevalent.[35] A significantly (P < 0.05) higher proportion of the lower middle class (99.0%) and upper middle class (100.0%) were cleaned their teeth on routine basis in comparison to the lower class (62.5%) and upper lower class (86.9%). The percentage of people performing oral hygiene practices decreased with the deterioration of the SES.

Toothbrush and toothpaste (79.2%) were the most commonly used aid in the present study followed by toothpaste and finger (5.4%). This was similar to the study by Kapoor et al.,[36] (90.3% patients cleaned their teeth with toothbrush and toothpaste), Freire et al.,[37] the most common oral hygiene aids were toothbrush (97.6%), toothpaste (90.5%), and dental floss (69.1%) and Paul et al.,[38] where most of the study subjects (69.20%) used both a toothbrush and toothpaste together, followed by the manual use of toothpaste or toothpowder (22.32%) as a method of cleaning their teeth. Similar findings were also noted by Jain et al.[39] among OPD patients in Jodhpur, Sharda and Sharda[40] among urban people of Udaipur, toothbrush (94.4%) and toothpaste (90.6%) were the main products used for the maintenance of oral hygiene, Chandra Shekar et al.[41] among the municipal employees of Mysore city, Bhat et al.[42] among the patients attending the Raja Rajeshwari Dental College, Bengaluru, and Pandya and Dhaduk[43] among the population in central Gujarat.

The toothbrush and toothpaste use is the most effective way of cleaning the teeth and maintaining the oral hygiene. To maximize the oral health, the American Dental Association and US Surgeon General recommend that individuals brush twice and floss at least once a day and have regular prophylactic dental visits.[44]

The use of no cleaning aids for personal oral hygiene was reported to be significantly more among the patients belonging to lower class (37.5%) and upper lower class (13.1%) in the present study. In the present study, toothbrush and toothpaste were being used significantly (P < 0.05) more by lower middle class (84.4%) and upper middle class (100.0%) in comparison to the lower class and upper lower class. This was similar to the study by Kadtane et al.,[45] 81.8% and 88.8% of the individuals from upper and upper middle class, respectively, used a toothbrush and toothpaste for cleaning followed by 66.2% middle class, 51.3% upper lower and 79.8% lower class. These results are similar to the study done by Chandra Shekar et al.,[41] where all the cases in the upper SES were using brush and paste for cleaning their teeth. The affordability of the people influences the choice of the oral hygiene aid as depicted in the present study.

In the present study, once daily cleaning of teeth was performed by majority (81.6%) of the subjects whereas very few subjects (10.8%) were cleaning their teeth twice daily. This was similar to the study by Bhat et al.,[42] in which 86.4% of them were brushing once a day and only 11.6% of the participants were brushing twice a day but was very less as compared to the US where 90% of the studied group were brushing twice a day.[46] This was different in comparison to 58% of the police recruits in the study by Dilip,[47] 67% of the Chinese urban adolescents in the study by Jiang et al.,[44] 62% of the Kuwaiti adults in a study by Al-Shammari et al.[48] and 50% of the middle-aged and 75% of the elderly Chinese adults in urban areas in a study by Zhu et al.,[49] 44.4% of the Chinese adolescents in a study by Zhu et al.,[50] 22% in the study by Sharda and Sharda[40] Whereas in the study by Paul et al.,[38] approximately one-third of the cases (35.71%) cleaned their teeth twice daily, while 58.93% cleaned them once daily.

A significantly higher frequency of cleaning teeth (twice a day) was reported among the lower middle class (17.2%) and upper middle class (21.5%) patients. This was similar to the study by Kadtane et al.,[45] where twice daily cleaning was reported by cases belonging to the upper, and lower middle class in comparison to the upper middle, upper lower and lower class.

The higher socioeconomic strata usually represent the people with better educational level thus leading to a better comprehension and awareness level. This might be the reason for twice daily practice to be more among higher socioeconomic strata. The best oral hygiene practices are brushing twice daily with a fluoridated toothpaste.

A significantly higher number of patients belonging to lower middle (19.8% and 3.1% respectively) and upper middle class (35.4% and 3.8%, respectively) cleaned their teeth for 3–5 min and more than 5 min. Similar results were also reported by Kadtane et al.,[45] a higher duration of cleaning teeth (2–3 and 3–4 min) was reported by patients from the lower middle and upper middle class whereas the high-class patients cleaned their teeth for 1–2 and 2–3 min.

Rinsing of mouth with plain water was reported by 89.4% patients in the present study with majority rinsing their mouth after meals (73.2%). This was much better than the study of Jain et al.,[39] only 29% of the sample population rinsed their mouth after eating food. The rinsing of mouth with water after meal was found to be significantly more among lower class patients (100%). This basic habit of oral hygiene was found to be quite among this study population.

In the present study, only 8.4% patients were using a mouthwash which was similar to the study by Paul et al.,[38] only 8.93% of the cases were using a mouthwash and Jain et al.,[39] 10% of the subjects used a mouth wash. A comparatively lesser proportion (4.8%) reported using a mouthwash in the study by Bhat et al.[42] The use of mouthwash was reported significantly (P < 0.05) more by patients belonging to upper middle class (19.0%) whereas none of the patients from lower class were using a mouthwash.

Cleaning of tongue was reported by 42.6% of patients in the present study. This was comparatively lower to the study by Kapoor et al.,[36] Tongue cleaning was reported by 67.2% of the patients but was in contrast with the study by Jain et al.,[39] in which only 20% of the studied population cleaned their tongue. The cleaning of tongue was reported by patients belonging to the upper middle (62.0%), lower middle class (52.1%) and upper lower class (30.0%) and there was significant (P < 0.05) across the different socioeconomic groups. This basic and simple method of maintaining oral hygiene is not very much popular among the study population which shows lack of oral health awareness.

The use of other oral hygiene aids like tongue cleaner and mouthwashes helps in keeping the good oral hygiene and maintaining the health of the oral cavity. Hence, to make people more aware of the different oral hygiene aids available, proper selection of these aids and use of these aids, the dental professionals should make their patients more aware of these accessory oral hygiene aids.

Visiting a dentist is still not considered a preventive dental behavior; at present, it only depends on the treatment needs.[38] The majority (60.2%) of the patients in the present study reported visiting a dentist only if a problem was there whereas only 3.0% and 4.0% visited a dentist once in 3 and 6 months, respectively. This was similar to the study by Kapoor et al.,[36] in which 75% of the patients visited the dentist only in problem and only 10% of the population visited the dentist on a regular basis after every 6 months, Paul et al.,[38] 59.38% cases had not visited a dentist in the last 6 months preceding the study and Bhat et al.,[42] 11.8% of them visited dentist once in a year, 1.4% of them visited every 6 months, and 4% of them visited the dentist regularly for their routine dental check-up. A significantly higher number of patients from the lower class (81.3%) never visited a dentist and were visiting for the first time. A significantly higher number of patients from the lower class (81.3%) never visited a dentist whereas a significantly higher number of patients from the lower middle (5.7%) and upper middle (8.9%) class visited a dentist once every 6 months.

The dental health care in India is mostly through the system of the private dental practitioners since the government facilities are limited in number and over-crowded with patients. In addition, the system of dental health insurance is not developed in India.

A high proportion (68.7%) of the patients in the present study were concerned about relief of pain only and would seek dental treatment for relief of pain only. These results were similar to the study done by Bhat et al.,[42] 82.8% had visited the dentist due to pain and Jain et al.[39] where 54% of the cases visited the dentist when they were in pain. Patients (100%) from lower class were concerned about relief of pain only whereas maintenance of healthy teeth and mouth was a major area of concern among patients belonging to the lower middle (20.8%) and upper middle class (36.7%).

The OR was calculated for SES as well as income, education and occupation separately controlling for these factors along with age and gender. The multinomial logistic analysis shows that the income level, education level, occupational status separately as well as the SES influence the cleaning of teeth by the patient, use of the oral hygiene aids by toothbrush and toothpaste/toothpowder, rinsing of the mouth with water, use of a mouthwash, tongue cleaning and using a tongue cleaner. The OR showed that these factors affect the affordability, awareness level and patients concerns about their oral health and oral hygiene.

The study by Paula et al.[38] showed that literates and higher SES (Class I) study cases had more “good practices” compared to illiterates, and lower SES (Class V), respectively; the differences appeared to be statistically significant (P < 0.05). These findings are in agreement with the findings reported in the present study. The study by Gundala et al.[51] showed that there was a strong association of lifestyle, education level, and socioeconomic status with periodontal health.

The study by Newman and Gift[52] the descriptive models have suggested that individuals with resources in the form of finances and education, and a sense of self-efficacy as expressed in attitudes toward oral health, had the greatest probability of having a regular pattern of preventive care. In the study by Arun et al.,[53] income was the major determinant of regular health care visits. The study by Yu et al.[54] also showed that health insurance and family income are most consistently related to adolescents' use of preventive medical and dental care. The study by Maupome et al.[55] showed that the financial and economic-related barriers affected oral self-care, including dental hygiene instructions.

The findings similar to the present study were also reported by Olusile et al.,[56] in which the use of toothbrush was significantly related to educational status and occupation. Younger persons, females, and more educated persons used toothbrushes for daily tooth cleaning. Similarly, all the sociodemographic characteristics were significantly related (P < 0.001) to daily frequency of tooth cleaning. Similar findings were also reported by Hjern et al. and Jamieson and Thomson.[28,57]

The brushing frequency was also related to the financial factors among present study with cleaning teeth once/twice a day beinf found to be significantly better among higher income categories such as 13,874–18,497 (OR = 1.497) and 18,498–36,996 (OR = 1.897). Similar findings were also reported by Almas et al.,[58] with brushing three times a day was common among >5000 SR monthly income group.

Hence, financial considerations, educational status, and occupation of the patient significantly impact oral health care in India. The findings from the present and various other studies have shown that the lower socioeconomic strata have poor oral hygiene practices which might be related to low affordability and low level of awareness. This combined with the long working hours might lead to neglection of the oral hygiene habits. Thus, the further study should be conducted to have an in-depth knowledge of the factors responsible for poor oral hygiene habits among this population. This can form basis for the suitable public health care programs targeting this population.

Various studies have shown an impact of SES on the oral health of an individual. It has also been proven that there is a significant association exists between the individual's oral health and awareness about the same. Individuals with lower socioeconomic group have less awareness and access to the oral health care. Individuals from lower socioeconomic groups unable to use the oral hygiene aids like mouthwash, interproximal brushes, and various medicated toothpaste because of their high cost. Comparatively individuals from higher economic status have access to all the above-mentioned oral health aids and also the awareness of its role in improving periodontal health.

This study is not without limitations, the major limitation is its dependence on self-reported information; such information is often subject to response bias due to the different interpretations individuals can give to the questions. In addition, the responses may have been influenced by the social acceptability of their responses which is referred to as the social desirability bias.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, the oral hygiene practices of the patients from upper and lower middle class was found to be satisfactory whereas it was poor among patients belonging to lower and upper lower class. The percentage of people using oral hygiene aids other than toothbrush and toothpaste was very less. Hence, the dental professionals need to educate and motivate people about the oral hygiene maintenance along with proper selection and use of the various oral hygiene aids.

The SES has an impact on the oral hygiene practices of the patients as it affects the affordability of the population. The development and implementation of well-structured dental health education programs on periodic basis are needed to improve and maintain suitable oral health standards among municipal employees with special emphasis on the lower SES strata.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Park K. 17th ed. Jabalpur, India: Banarsidas Bhanot Publishers; 2002. Concepts of Health and Disease. Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine; pp. 11–47. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliver RC, Brown LJ, Loe H. Variations in the prevalence and extent of periodontitis. J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;122:43–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8177(91)26016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petridou E, Athanassouli T, Panagopoulos H, Revinthi K. Socio-demographic and dietary factors in relation to dental health among Greek adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24:307–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1996.tb00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freire Mdo C, de Melo RB, Almeida e Silva S. Dental caries prevalence in relation to socioeconomic status of nursery school children in Goiânia-GO, Brazil. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24:357–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1996.tb00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whittle JG, Whittle KW. Household income in relation to dental health and dental health behaviours: The use of super profiles. Community Dent Health. 1998;15:150–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Hosani E, Rugg-Gunn A. Combination of low parental educational attainment and high parental income related to high caries experience in pre-school children in Abu Dhabi. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:31–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorgensen EB. Effect of socio-economic and general health status on periodontal conditions in old age. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:83. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oral Health U.S. The National Institute of Dental and Cranio-facial Research, USA. 2002. [Last accessed on 2014 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/datastatistics/surgeongeneral/report/executivesummary.htm .

- 9.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Glass R. Social capital and self-rated health: A contextual analysis. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1187–93. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malmström M, Sundquist J, Johansson SE. Neighborhood environment and self-reported health status: A multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1181–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yen IH, Kaplan GA. Poverty area residence and changes in depression and perceived health status: Evidence from the Alameda county study. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:90–4. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subramania SV, Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Does the state you live in make a difference? Multilevel analysis of self-rated health in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subramanian SV, Kim DJ, Kawachi I. Social trust and self-rated health in US communities: A multilevel analysis. J Urban Health. 2002;79(4 Suppl 1):S21–34. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.suppl_1.S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Browning CR, Cagney KA. Neighborhood structural disadvantage, collective efficacy, and self-rated physical health in an urban setting. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:383–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy BP, Kawachi I, Glass R, Prothrow-Stith D. Income distribution, socioeconomic status, and self rated health in the United States: Multilevel analysis. BMJ. 1998;317:917–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7163.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soobader M, LeClere FB, Hadden W, Maury B. Using aggregate geographic data to proxy individual socioeconomic status: Does size matter? Am J Public Health. 2001;91:632–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.4.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stafford M, Marmot M. Neighbourhood deprivation and health: Does it affect us all equally? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:357–66. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humphreys K, Carr-Hill R. Area variations in health outcomes: Artefact or ecology. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:251–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones K, Duncan C. Individuals and their ecologies: Analysing the geography of chronic illness within a multilevel modelling framework. Health Place. 1995;1:27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reijneveld SA. Neighbourhood socioeconomic context and self reported health and smoking: A secondary analysis of data on seven cities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:935–42. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.12.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Locker D, Ford J. Evaluation of an area-based measure as an indicator of inequalities in oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994;22:80–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1994.tb01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Locker D, Ford J. Using area-based measures of socioeconomic status in dental health services research. J Public Health Dent. 1996;56:69–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: Continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century – The approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(Suppl 1):3–23. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunst A, Mackenbach J. Copenhagen: WHO, Regional Office for Europe; 1997. [Last accessed on 2014 Nov 25]. Measuring Socio.economic Inequalities in Health. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/14133604_Measuring_the_Magnitude_of_Socio-Economic_Inequalities_in_Health_An_Overview_of_Available_Measures_Illustrated_with_Two_Examples_from_Europe . [Google Scholar]

- 25.Locker D. Deprivation and oral health: A review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:161–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.280301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watt RG. From victim blaming to upstream action: Tackling the social determinants of oral health inequalities. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enjary C, Tubert-Jeannin S, Manevy R, Roger-Leroi V, Riordan PJ. Dental status and measures of deprivation in Clermont-Ferrand, France. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34:363–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jamieson LM, Thomson WM. Adult oral health inequalities described using area-based and household-based socioeconomic status measures. J Public Health Dent. 2006;66:104–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2006.tb02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.López R, Fernández O, Baelum V. Social gradients in periodontal diseases among adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34:184–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders AE, Slade GD, Turrell G, John Spencer A, Marcenes W. The shape of the socioeconomic-oral health gradient: Implications for theoretical explanations. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34:310–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sisson KL. Theoretical explanations for social inequalities in oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:81–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petersen PE. Sociobehavioural risk factors in dental caries – International perspectives. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:274–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheiham S, Watt RG. Inequalities in oral health. In: Gordon D, Shaw M, Dorling D, Smith GD, editors. Inequalities in Health. Bristol: The Policy Press, University of Bristol; 1999. pp. 240–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar N, Gupta N, Kishore J. Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic scale: Updating income ranges for the year 2012. Indian J Public Health. 2012;56:103–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.96988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goel S, Goel BR, Bhongade ML. Oral health status of young adults using indigenous oral hygiene methods. Stomatol India. 1992;5:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kapoor D, Gill S, Singh A, Kaur I, Kapoor P. Oral hygiene awareness and practice amongst patients visiting the department of periodontology at a dental college and hospital in North India. Indian J Dent. 2014;5:64–8. doi: 10.4103/0975-962X.135262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freire MD, Sheiham A, Bino YA. Sociodemographic factors associated with oral hygiene habits in Brazilian adolescents. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2007;10:606–14. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paul B, Basu M, Dutta S, Chattopadhyay S, Sinha D, Misra R. Awareness and practices of oral hygiene and its relation to sociodemographic factors among patients attending the general outpatient department in a tertiary care hospital of Kolkata, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2014;3:107–11. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.137611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jain N, Mitra D, Ashok KP, Dundappa J, Soni S, Ahmed S. Oral hygiene-awareness and practice among patients attending OPD at Vyas Dental College and Hospital, Jodhpur. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:524–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.106894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharda A, Sharda S. Factors influencing choice of oral hygiene products used among the population of Udaipur, India. Int J Dent Clin. 2010;2:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chandra Shekar BR, Reddy C, Manjunath BC, Suma S. Dental health awareness, attitude, oral health-related habits, and behaviors in relation to socio-economic factors among the municipal employees of Mysore city. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2011;4:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhat PK, Kumar A, Aruna CN. Preventive oral health knowledge, practice and behaviour of patients attending dental institution in Bangalore, India. J Int Oral Health. 2010;2:17–6. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandya H, Dhaduk R. Oral hygiene status in central Gujarat, 2010 – An epidemiological study. J Dent Sci. 2012;2:51–3. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang H, Petersen PE, Peng B, Tai B, Bian Z. Self-assessed dental health, oral health practices, and general health behaviors in Chinese urban adolescents. Acta Odontol Scand. 2005;63:343–52. doi: 10.1080/00016350500216982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kadtane SS, Bhaskar DJ, Agali C, Punia H, Gupta V, Batra M, et al. Periodontal health status of different socio-economic groups in out-patient department of TMDC & RC, Moradabad, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZC61–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8565.4624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Survey of family toothbrushing practices. Bureau of dental health education. Bureau of Economic Research & Statistics. J Am Dent Assoc. 1966;72:1489–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dilip CL. Health status, treatment requirements, knowledge and attitude towards oral health of police recruits in Karnataka. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2005;5:20–34. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Shammari KF, Al-Ansari JM, Al-Khabbaz AK, Dashti A, Honkala EJ. Self-reported oral hygiene habits and oral health problems of Kuwaiti adults. Med Princ Pract. 2007;16:15–21. doi: 10.1159/000096134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu L, Petersen PE, Wang HY, Bian JY, Zhang BX. Oral health knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of adults in China. Int Dent J. 2005;55:231–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2005.tb00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu L, Petersen PE, Wang HY, Bian JY, Zhang BX. Oral health knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of children and adolescents in China. Int Dent J. 2003;53:289–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2003.tb00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gundala R, Chava VK. Effect of lifestyle, education and socioeconomic status on periodontal health. Contemp Clin Dent. 2010;1:23–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.62516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newman JF, Gift HC. Regular pattern of preventive dental services – A measure of access. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:997–1001. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90239-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arun R, Karthik SJ, Nagarakanti S, Kumar TS, Arun KV, Usharani MV. Influence of literacy and socioeconomic status on awareness of periodontal disease. Med Res Chron. 2015;2:94–107. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu SM, Bellamy HA, Schwalberg RH, Drum MA. Factors associated with use of preventive dental and health services among U.S. adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29:395–405. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maupome G, Aguirre-Zero O, Westerhold C. Qualitative description of dental hygiene practices within oral health and dental care perspectives of Mexican-American adults and teenagers. J Public Health Dent. 2015;75:93–100. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olusile AO, Adeniyi AA, Orebanjo O. Self-rated oral health status, oral health service utilization, and oral hygiene practices among adult Nigerians. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:140. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hjern A, Grindefjord M, Sundberg H, Rosen M. Social inequality in oral health and use of dental care in Sweden. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29:167–74. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Almas K, Al-Malik TM, Al-Shehri MA, Skaug N. The knowledge and practices of oral hygiene methods and attendance pattern among school teachers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:1087–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]