Abstract

Background:

Hyaluronan is a critical component of the extracellular matrix and contributes significantly to tissue hydrodynamics and cell migration and proliferation. Studies have demonstrated its anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and regenerative effects. The present study aimed to assess the clinical effects of the subgingival application of 0.8% hyaluronic acid gel as an adjunct to scaling and root planing (SRP) in the treatment of generalized chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods:

Patients with chronic periodontitis were recruited to participate in a study with a split-mouth design and provided informed consent. One hundred sites were included in the study and divided into fifty test sites and fifty control sites. These were assessed for plaque index (PI), gingival index (GI), pocket probing depths, and relative attachment level (RAL) at-pretreatment (baseline), 4, and 12 weeks posttreatment. The patients received full-mouth SRP. A 0.8% hyaluronan gel was administered subgingivally in the test sites at baseline and after 1 week. Significant differences between test and control were evaluated using the t-test, analysis of variance (test) followed by Bonferroni post hoc test.

Results:

A significant reduction in PI and GI was observed in both groups at 12 weeks (P < 0.05). Significant reduction in the pocket probing depths and gain RAL was observed in both the groups as compared to baseline (P < 0.05). The hyaluronan group compared to control at 12 weeks showed statistically significant reduction in the probing pocket depth and gain in RAL (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

The subgingival application of 0.8% hyaluronan gel in conjunction with SRP may have a beneficial effect on periodontal health in patients with chronic periodontitis.

Keywords: Dental plaque, hyaluronan, periodontitis

INTRODUCTION

Chronic periodontitis is a multifactorial disease, where putative periodontopathogens trigger chronic inflammatory and immune responses. Bacteria associated with periodontal diseases are usually found in biofilms protecting them from antimicrobial agents.

Conventional, nonsurgical periodontal therapy consists of supragingival and subgingival tooth debridement. Mechanical debridement is usually effective in both disturbing the biofilm and reducing the bacterial load. Sometimes, it may not be sufficient to control the disease due to complex anatomy of the root and the contours of the lesion.[1] In addition, certain microorganisms have the ability to invade and reside within the gingival tissues providing a reservoir for the bacteria that rapidly repopulate the pocket. The base of the pocket is difficult to access for periodontal instrumentation and hence mechanical methods alone are insufficient.[2,3]

To overcome this, systemic antimicrobials delivery was initiated to augment the effects of conventional mechanical periodontal therapy. However, side effects including hypersensitivity, gastrointestinal intolerance, and the development of bacterial resistance have been reported with systemic antimicrobials.[4] Some studies also reported poor results of the drug to achieve an adequate concentration at the site of action, and/or due to the inability of the active product to be retained locally for a sufficient period.[5]

To avoid the undesirable effects of systemic antibiotic administration, several local drug delivery (LDD) systems have been developed. Local delivery of antibiotics into the pocket achieves a greater concentration of the drug locally, proving bactericidal for most periopathogens and at the same time exhibits negligible impact on the microflora residing in other parts of the body.[6]

The concept of controlled-release local delivery of therapeutic agents, either antimicrobials or anti-inflammatory agents, was advocated and developed into a viable concept primarily by Dr. Max Goodson in 1979. He developed hollow fibers of cellulose acetate filled with tetracycline.

Hyaluronic acid (HA) was discovered in 1934 by Karl Mayer and his colleague John Palmer, Scientists at Columbia University, New York, who isolated a chemical substance from the vitreous jelly of cow's eyes. They proposed the name “Hyaluronic Acid” as it was derived from the Greek word hyalos (glass) and contained two sugar molecules one of which was uronic acid.[7]

Hyaluronan, a nonsulfated glycosaminoglycan, is widely distributed throughout connective tissue and epithelial and neural tissues. It is a critical component of the extracellular matrix and contributes significantly to tissue hydrodynamics and cell migration and proliferation. Hyaluronan is also produced by fibroblasts in the presence of endotoxin; it plays an important anti-inflammatory role through the inhibition of tissue destruction and facilitates healing.[8,9]

The use of hyaluronan in the treatment of inflammatory processes has been established in several settings such as in the treatment of osteoarthritis,[10] cataract surgery,[11] and radioepithelitis following radiation therapy and intra-articularly injected hyaluronate alleviated clinical characteristics of rheumatoid arthritis.[12,13]

HA plays important role in cell adhesion, migration, and differentiation mediated by the various HA binding proteins and cell-surface receptors. It has been studied as a metabolite or diagnostic marker of inflammation in the gingival crevicular fluid as well as a significant factor in growth, development, and repair of tissues.[14]

The beneficial effect of a hyaluronan-containing gel during the therapy of plaque-induced gingivitis is proven by clinical and paraclinical variables.[15] Yet, a coherent and conclusive evaluation of the possible effect of HA in the treatment of periodontal diseases has not been possible due to a large variability in the limited literature that is available.[16]

Thus, the present study aimed to assess the clinical effects of subgingival application of 0.8% HA gel as an adjunct to scaling and root planing (SRP) in the treatment of generalized chronic periodontitis.

Aim

The aim of this study is to compare the effect of the local delivery of HA as an adjunct to SRP versus SRP alone in the treatment of chronic periodontitis.

Objectives

To assess the clinical effects of subgingival application of 0.8% HA gel as an adjunct to SRP

To test the efficacy, equivalence or superiority of subgingival administration of HA gel in addition to SRP as compared to SRP alone in the treatment of chronic periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of data

Patients were recruited from the outpatient department of Periodontics. The ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee.

Inclusion criteria

Subjects between the age group of 30 and 60 years

Subjects who readily gave informed consent for the study

Patients with a minimum number of 20 teeth

Patients with chronic periodontitis, with probing pocket depth (PPD) ≥5 mm in at least 1 tooth in the contralateral quadrants [Figure 1a].

Figure 1.

(a) Pocket Probing with stent in position; (b) Application of 0.8% Hyaluronic acid gel with blunt cannula; (c) Periodontal dressing placed

Exclusion criteria

Patients who consumed tobacco in any form

Patients who had undergone periodontal therapy in the last 6 months

Patients who had received antibiotic therapy in the previous 3 months

Patients who were taking or had consumed vitamin supplements, anti-inflammatory agents, or statins in the previous 3 months.

Patients with any systemic disorder affecting periodontal health

Patients with infectious conditions other than periodontitis

Regular users of mouthwash

Chronic alcoholics.

Study design

Informed written consent was obtained from all the subjects before participating in the study.

All study subjects underwent an oral examination, and the below-stated indices were recorded by a single examiner.

Baseline periodontal assessment included as follows:

In each recruited patient, teeth with PPD of ≥5 mm were allotted to either.

Group A - (n = 50): Control sites: Treated with SRP only or

Group B - (n = 50): Test sites: Treated with SRP + hyaluronan gel 0.8%.

Full mouth SRP was performed for all the subjects. The experimental sites were gently dried using an air syringe and isolated with cotton rolls. This was followed by subgingival administration of 0.2 ml 0.8% HA gel into selected sites following SRP [Figure 1b]. The 0.8% HA gel was in the form of preloaded 1 ml syringes with a blunt cannula (Gengigel® 0.8%, Ricerfarma) [Figure 2]. The test sites were then covered with a periodontal dressing (Coe-Pak®) for retention of the material [Figure 1c]. Each subject was told to report immediately if the pack was dislodged before the scheduled recall visit or if any sort of discomfort, pain, burning sensation, or any allergic reaction occurred.

Figure 2.

0.8% hyaluronic acid gel (Gengigel® Prof Syringes, Ricerfarma)

At the 1st week recall, the same procedure was repeated. HA gel was readministered at the test sites after removing periodontal dressing. The periodontal dressing was placed again, and the instructions were repeated.

Subjects were recalled after 7 days for removal of the periodontal dressing, reinforcing oral hygiene maintenance instructions, and recording clinical parameters. Recall visits were scheduled at the end of 4 weeks and 12 weeks.

Statistical analysis

A convenient sample size of 100 sites was included under 5% alpha error and 80% of power of the test to detect the significant difference. All data collected was entered in Microsoft Excel (MS office version 2010) and tabulated. Data analysis was done using Windows PC-based SPSS version 17 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The one-way analysis of variance was used to compare the intra-group parameters at various time intervals (baseline, 4 weeks, and 12 weeks) followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. The Student's t-test was used to determine whether a statistically significant difference existed between the test and the control groups at different time intervals. Statistical significance was set at 5% level of significance (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

One hundred sites were selected from nine patients, showing PPD ≥5 mm in at least one tooth in the contralateral quadrants. These patients, in the age group of 30–60 years, satisfied the inclusion criteria of having chronic periodontitis. All subjects completed the study. The periodontal parameters were assessed at baseline, 4 weeks, and 12 weeks.

For PI and GI, site-specific scores were recorded and tabulated. For PPD and RAL, the deepest probing depth and its corresponding RAL, for the selected tooth, were recorded and tabulated. These recordings were subjected to both intra- and inter-group comparisons.

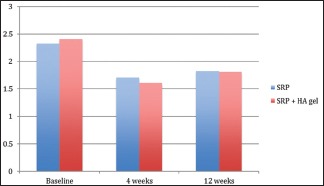

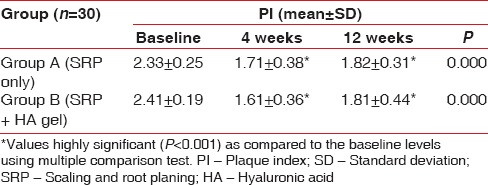

Plaque index

Inter-group comparisons of PI at each follow-up revealed no significant difference between the groups at any stage during the follow-up as seen in Table 1 and Graph 1. Comparison at different time intervals during follow-up showed that there was a statistically significant reduction in the PI scores at each follow-up as compared to baseline. However, there was no significant difference found between 4 weeks and 12 weeks follow-up. These findings were true for both the test and the control group [Table 2 and Graph 2].

Table 1.

Inter-group comparison of plaque index using Student's t-test

Graph 1.

Inter-group comparison of plaque index

Table 2.

Intra-group comparison of plaque index using repeated measures of analysis of variance

Graph 2.

Intra-group comparison of plaque index

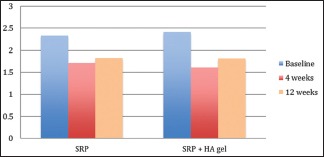

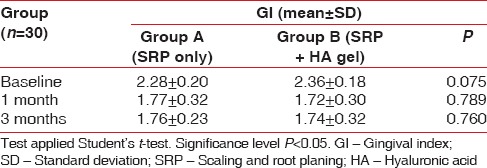

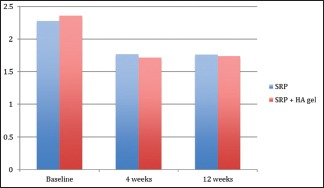

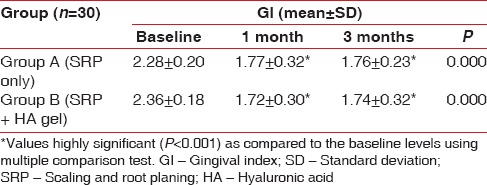

Gingival index

Inter-group comparisons of GI at each follow-up carried out by t-test revealed no significant difference between the groups at any stage during the follow-up as seen in Table 3 and Graph 3. Comparison at different time intervals during follow-up done showed that there was a statistically significant reduction in the GI scores at each follow-up as compared to baseline. However, there was no significant difference found between 4 weeks and 12 weeks follow-up. These findings were true for both the test and the control group [Table 4 and Graph 4].

Table 3.

Inter-group comparison of gingival index using Student's t-test

Graph 3.

Inter-group comparison of gingival index

Table 4.

Intra-group comparison of gingival index using repeated measures of analysis of variance

Graph 4.

Intra-group comparison of gingival index

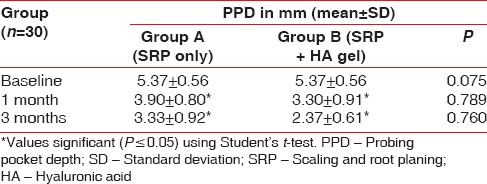

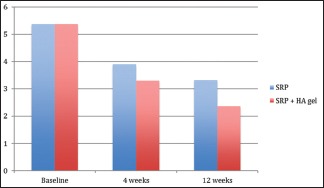

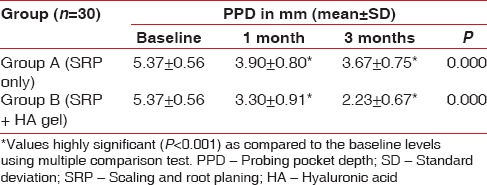

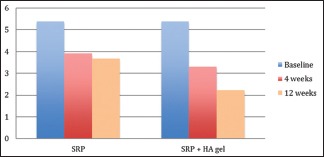

Probing pocket depth

There was no statistical difference found at baseline between the test and the control group. However, there was significantly significant reduction in the probing depths in test group as compared to the control group at both, 4 weeks (P = 0.044) and 12 weeks (P = 0.041) recall as shown in Table 5 and Graph 5. Comparison at different time intervals during follow-up showed a statistically significant reduction in the probing depths at each follow-up as compared to baseline. A statistically significant reduction was also seen between the 4 weeks and the 12 weeks follow-up. These findings were true for both the test and the control group [Table 6 and Graph 6].

Table 5.

Inter-group comparison of probing pocket depth using Student's t-test

Graph 5.

Inter-group comparison of probing pocket depth

Table 6.

Intra-group comparison of probing pocket depth using repeated measures of analysis of variance

Graph 6.

Intra-group comparison of probing pocket depth

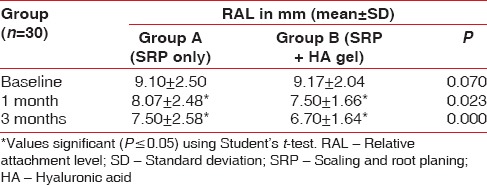

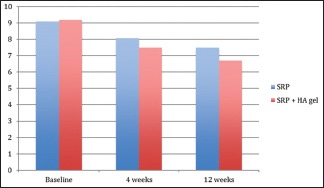

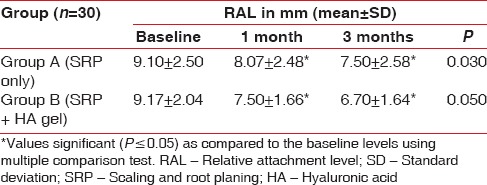

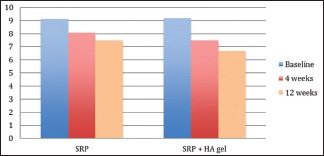

Relative attachment level

There was no statistical difference found at baseline between the test and the control group. However, there was a significant reduction in the RALs in test group as compared to the control group at both, 4 weeks (P = 0.00) and 12 weeks (P = 0.00) recall as shown in [Table 7 and Graph 7]. Comparison at different time intervals during follow-up showed a statistically significant reduction in the RALs at each follow-up as compared to baseline. However, no statistically significant reduction was seen between the 4 weeks and the 12 weeks follow-up. These findings were true for both the test and the control group [Table 8 and Graph 8].

Table 7.

Inter-group comparison of relative attachment level using Student's t-test

Graph 7.

Inter-group comparison of relative attachment level

Table 8.

Intra-group comparison of relative attachment level using repeated measures of analysis of variance

Graph 8.

Intra-group comparison of relative attachment level

DISCUSSION

Periodontal diseases are plaque-associated infections initiated by the accumulation and maturation of pathogenic biofilms of the surface of the teeth and oral mucosal surfaces. Periodontitis appears in a generalized form but more often appears in local areas in a patient's mouth or is reduced to localized areas after Phase I treatment.[20]

Nonsurgical therapy remains the cornerstone of periodontal treatment.[21] However, the ability of the clinician to gain access to deep pockets, during SRP, often results in a substantial variation in its effectiveness.[20]

To overcome these limitations, LDD systems were developed.[6] A number of studies have reported a variety of LDD systems as adjunct to SRP. However, the outcomes obtained from these results have been questioned for their clinical superiority as compared to the conventional debridement and have emphasized on the need for further research for the same.[22]

HA has been attributed a protective role in inflammatory damage. Hyaluronan in its various forms, shows bacteriostatic, fungistatic, anti-inflammatory, anti-edematous, osteoinductive, and pro-angiogenetic properties, thereby promoting wound healing in a variety of tissues.[14]

Healing of periodontal wound includes a series of highly reproducible and rigidly controlled biologic events which includes inflammation, granulation tissue formation, epithelium formation, and tissue remodeling. Hyaluronan plays an important role through all the stages of periodontal wound healing.[14]

Håkansson et al. suggested role of hyaluronan in migration and adherence of Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN's)and macrophages at the inflamed site and the phagocytosis and killing of invading microbes. Such events would allow counteraction of colonization and proliferation of anaerobic pathogenic bacteria in the gingival crevice and adjacent periodontal tissues.[23]

Hyaluronan itself may also prevent periodontal pathogen colonization by directly preventing microbial proliferation. It may also indirectly act to moderate inflammation and stabilize the granulation tissue by preventing degradation of the extracellular matrix proteins by serine proteinases derived from inflammatory cells as healing progresses.[14]

HA has shown to accelerate bone regeneration by means of chemotaxis, proliferation, and differentiation of mesenchymal cells. HA shares bone induction characteristics with osteogenic substances such as bone morphogenetic protein-2 and osteopontin.[24]

A number of studies on HA have advocated its use as monotherapy or as adjunct to nonsurgical and/or surgical periodontal treatment to reduce inflammation and promote wound healing.[13,25,26,27] In a recent systemic review, the authors concluded that coherent and conclusive evaluation of the possible effect of HA in the treatment of periodontal diseases has not yet been possible and a positive additional effect of HA application should be repeatedly reported in controlled clinical settings.[16]

Thus, we evaluated the effect of locally delivered hyaluronan gel used in adjunct with SRP in the treatment of chronic periodontitis.

The gel used in our study (0.8% Gengigel Prof®, Ricerfarma) contains hyaluronan, xylitol, and excipients. No undesirable side effects have been reported by the patients in any previous studies. It is available in a preformed syringe form with blunt cannulas for subgingival delivery for the gel.[28]

Our study design was a randomized, controlled trial in accordance with the recommendations by Pihlström in 1997.[29]

On the test sites, after completion of SRP, 0.2 ml of 0.8% HA gel was subgingivally placed using the preformed syringes. The hyaluronan gel was reapplied at 1 week posttreatment. This study design was similar to the study reported by Johannsen et al.[13]

Periodontal pack (Coe-Pack) was given after HA application.[13] This would help retain the drug subgingivally for maximum period.

The clinical parameters were assessed at baseline, 4 weeks, and 12 weeks. The difference between the mean baseline values of both the test group and the control group for all the clinical parameters was statistically insignificant. Thus, the randomization was successful.

The inter-group comparison, at 4 weeks and 12 weeks, showed that the difference between the mean PI and GI was insignificant between the test and the control group. However, intra-group comparison in both the test and the control group at the recall appointments showed a highly statistically significant difference from the baseline. This reinforces the already ingrained importance of SRP in nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Hawthorne effect could also be a contributing factor where the subjects enrolled in the study maintained better oral hygiene leading to significant improvement in the PI and the GI.[30]

In the intra-group comparison for PPD, in both test and the control groups, a statistically significant reduction was observed at 4 weeks and 12 weeks. However, in the inter-group comparison, a statistically significant difference was seen in the test group as compared to the control group at both 4 weeks and 12 weeks.

Thus, SRP did have a significant role in PPD reduction. However, application of HA gel augmented its effects, and lead to further reduction in the PPD.

Periodontal pockets are pathognomic signs of periodontal disease. A number of studies have documented significant improvement in probing depth variable when HA gel was used in conjunction with SRP.[16] Johannsen et al., also used 0.8% HA gel in combination with SRP, found that reduction in probing depth between baseline and 12 weeks was statistically significantly greater for the test group than the control group (1.0 + 0.3 mm and 0.8 + 0.2 mm), respectively.[13]

Even in studies wherein the modes of application of HA gel and the frequency differed in the treatment of chronic periodontitis patients, significant reductions in pocket depths were observed.[28,31,32,33,34]

Only two studies by Xu et al.[35] and Gontiya and Galgali[28] that we found in the literature have contradictory results. However, in both the studies, the concentration of HA was 0.2%. Thus, we could infer that a higher concentration of HA is needed for better clinical outcomes.

In a recent systematic review on the effects of hyaluronan in periodontal therapy, the authors concluded that HA has definite positive effect on the probing depth reduction as compared to SRP alone.[16]

Apart from the already established role of HA on wound healing, this reduction in the probing depth could also be accredited to the fact that hyaluronan has been shown to directly interfere with inflammation. HA gel has bacteriostatic effect on periodontal pathogens.[25,27,36] These properties might reduce bacterial load in the initial stage of healing and hence may have resulted in better improvement in test group patients than control group. HA has been said to have regenerative and osteoinductive potential.[37]

In the present study, both the groups showed a statistically significant gain in the attachment at 4 weeks and 12 weeks. However, the test group showed a statistically significant improvement in RAL as compared to the control group. All the properties discussed so far attributed to hyaluronan could ensue these positive effects on the attachment level.

Another study by Chauhan et al. showed a similar gain in the attachment level in the group where HA was used in conjunction with SRP.[32]

Most of the studies have also shown an enhancement in the attachment levels wherein HA was used as an adjunct to SRP. They, however, did not find a statistically significant difference between the test and control groups.[13,27,28,31,34,35] This could be attributed to the vast difference in the study design such as the severity of the disease in the subjects, the concentration of the gel, and the mode of application, frequency.

Hyaluronan has also been studied as an adjunct to periodontal surgical treatment. In a case series by Vanden Bogaerde,[38] wherein open flap debridement (OFD) was performed with adjunct use of hyaluronan for the treatment of intrabony defects, clinical attachment level (CAL) gain after 12 months was observed. CAL gains ranging from 1.9 to 3.5 mm[39,40] were observed when HA was used in adjunct to modified Widman flap or OFD. In another study, HA gel application as adjunct to guided tissue regeneration (GTR) resulted in statistically significant larger radiographic bone gain comparing to only GTR.[41]

Thus, these findings support the gain in the clinical attachment we found in our study owing to the favorable properties of hyaluronan.

The application of hyaluronan, thus, has an irrefutable advantage on the various gingival and periodontal clinical parameters in the treatment of periodontal disease.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Clinicians are challenged with managing patients with periodontitis of varying extent and severity. Treatment options range from SRP to SRP with adjunctive treatments to surgical interventions.

Hyaluronan as an LDD is gaining foothold too. Due to its anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial and regenerative properties, it is being evaluated as an adjunct to both nonsurgical and surgical therapy in periodontology.

In the present study, the clinical effects of subgingival application of 0.8% hyaluronan gel as an adjunct to SRP in the treatment of generalized chronic periodontitis were assessed.

The following conclusions were drawn at the end of the study:

There was a significant improvement in all the parameters found at different time intervals

There was a significant improvement in the primary variables of the periodontal parameters, i.e., PPDs and attachment levels in the sites wherein hyaluronan was used as compared to where it was not.

Within the limitations of the current study, subgingival placement of 0.8% HA gel along with SRP provided a significant improvement in periodontal parameters in the test sites after a 3-month period when compared with control sites. Thus, hyaluronan is surfacing as a promising prospect in the treatment of periodontitis. However, further studies with larger sample size are needed in this field to substantiate the assessment of the result of the said periodontal therapy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adriaens PA, De Boever JA, Loesche WJ. Bacterial invasion in root cementum and radicular dentin of periodontally diseased teeth in humans. A reservoir of periodontopathic bacteria. J Periodontol. 1988;59:222–30. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.4.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rams TE, Slots J. Local delivery of antimicrobial agents in the periodontal pocket. Periodontol 2000. 1996;10:139–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1996.tb00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golub LM, Lee HM, Lehrer G, Nemiroff A, McNamara TF, Kaplan R, et al. Minocycline reduces gingival collagenolytic activity during diabetes. Preliminary observations and a proposed new mechanism of action. J Periodontal Res. 1983;18:516–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1983.tb00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Winkelhoff AJ, Rams TE, Slots J. Systemic antibiotic therapy in periodontics. Periodontol 2000. 1996;10:45–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1996.tb00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodwad V, Vaish S, Mahajan A, Chhokra M. Local drug delivery in periodontics: A strategic intervention. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2012;4:30–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodson JM, Haffajee A, Socransky SS. Periodontal therapy by local delivery of tetracycline. J Clin Periodontol. 1979;6:83–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1979.tb02186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vedamurthy M. Soft tissue augmentation – Use of hyaluronic acid as dermal filler. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:383–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartold PM, Page RC. Hyaluronic acid synthesized by fibroblasts cultured from normal and chronically inflamed human gingivae. Coll Relat Res. 1986;6:365–77. doi: 10.1016/s0174-173x(86)80006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moseley R, Waddington RJ, Embery G. Hyaluronan and its potential role in periodontal healing. Dent Update. 2002;29:144–8. doi: 10.12968/denu.2002.29.3.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams ME, Atkinson MH, Lussier AJ, Schulz JI, Siminovitch KA, Wade JP, et al. The role of viscosupplementation with hylan G-F 20 (Synvisc) in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: A Canadian multicenter trial comparing hylan G-F 20 alone, hylan G-F 20 with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and NSAIDs alone. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1995;3:213–25. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(05)80013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neumayer T, Prinz A, Findl O. Effect of a new cohesive ophthalmic viscosurgical device on corneal protection and intraocular pressure in small-incision cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:1362–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuno H, Yudoh K, Kondo M, Goto M, Kimura T. Biochemical effect of intra-articular injections of high molecular weight hyaluronate in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Inflamm Res. 1999;48:154–9. doi: 10.1007/s000110050439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johannsen A, Tellefsen M, Wikesjö U, Johannsen G. Local delivery of hyaluronan as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1493–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahiya P, Kamal R. Hyaluronic acid: A boon in periodontal therapy. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:309–15. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.112473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jentsch H, Pomowski R, Kundt G, Göcke R. Treatment of gingivitis with hyaluronan. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:159–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.300203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertl K, Bruckmann C, Isberg PE, Klinge B, Gotfredsen K, Stavropoulos A. Hyaluronan in non-surgical and surgical periodontal therapy: A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42:236–46. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Löe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol. 1967;38:610–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pihlstrom BL. Measurement of attachment level in clinical trials: Probing methods. J Periodontol. 1992;63(12 Suppl):1072–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.12s.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Killoy WJ. Chemical treatment of periodontitis: Local delivery of antimicrobials. Int Dent J. 1998;48(3 Suppl 1):305–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.1998.tb00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drisko CH. Nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000. 2001;25:77–88. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2001.22250106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonito AJ, Lux L, Lohr KN. Impact of local adjuncts to scaling and root planing in periodontal disease therapy: A systematic review. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1227–36. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.8.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Håkansson L, Hällgren R, Venge P. Regulation of granulocyte function by hyaluronic acid. In vitro and in vivo effects on phagocytosis, locomotion, and metabolism. J Clin Invest. 1980;66:298–305. doi: 10.1172/JCI109857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendes RM, Silva GA, Lima MF, Calliari MV, Almeida AP, Alves JB, et al. Sodium hyaluronate accelerates the healing process in tooth sockets of rats. Arch Oral Biol. 2008;53:1155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pirnazar P, Wolinsky L, Nachnani S, Haake S, Pilloni A, Bernard GW. Bacteriostatic effects of hyaluronic acid. J Periodontol. 1999;70:370–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engström PE, Shi XQ, Tronje G, Larsson A, Welander U, Frithiof L, et al. The effect of hyaluronan on bone and soft tissue and immune response in wound healing. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1192–200. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.72.9.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eick S, Renatus A, Heinicke M, Pfister W, Stratul SI, Jentsch H. Hyaluronic acid as an adjunct after scaling and root planing: A prospective randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2013;84:941–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.120269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gontiya G, Galgali SR. Effect of hyaluronan on periodontitis: A clinical and histological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:184–92. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.99260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pihlstrom BL. Overview of periodontal clinical trials utilizing anti-infective or host modulating agents. Ann Periodontol. 1997;2:153–65. doi: 10.1902/annals.1997.2.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanes PJ, Purvis JP. Local anti-infective therapy: Pharmacological agents. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003;8:79–98. doi: 10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilloni A, Annibali S, Dominici F, Di Paolo C, Papa M, Cassini MA, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of an hyaluronic acid-based biogel on periodontal clinical parameters. A randomized-controlled clinical pilot study. Ann Stomatol (Roma) 2011;2:3–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chauhan AS, Bains VK, Gupta V, Singh GP, Patil SS. Comparative analysis of hyaluronan gel and xanthan-based chlorhexidine gel, as adjunct to scaling and root planing with scaling and root planing alone in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A preliminary study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013;4:54–61. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.111619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koshal A, Patel P, Bolt R, Bhupinder D, Galgut P. A comparison in postoperative healing of sites receiving non-surgical debridement augmented with and without a single application of hyaluronan 0.8% gel. Dent Trib Middles East Afr Ed. 2012;10:8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polepalle T, Srinivas M, Swamy N, Aluru S, Chakrapani S, Chowdary BA. Local delivery of hyaluronan 0.8% as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A clinical and microbiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015;19:37–42. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.145807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu Y, Höfling K, Fimmers R, Frentzen M, Jervøe-Storm PM. Clinical and microbiological effects of topical subgingival application of hyaluronic acid gel adjunctive to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1114–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.8.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodrigues SV, Acharya AB, Bhadbhade S, Thakur SL. Hyaluronan-containing mouthwash as an adjunctive plaque-control agent. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2010;8:389–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ballini A, Cantore S, Capodiferro S, Grassi FR. Esterified hyaluronic acid and autologous bone in the surgical correction of the infra-bone defects. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6:65–71. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vanden Bogaerde L. Treatment of infrabony periodontal defects with esterified hyaluronic acid: Clinical report of 19 consecutive lesions. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2009;29:315–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briguglio F, Briguglio E, Briguglio R, Cafiero C, Isola G. Treatment of infrabony periodontal defects using a resorbable biopolymer of hyaluronic acid: A randomized clinical trial. Quintessence Int. 2013;44:231–40. doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a29054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fawzy El-Sayed KM, Dahaba MA, Aboul-Ela S, Darhous MS. Local application of hyaluronan gel in conjunction with periodontal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16:1229–36. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0630-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engström PE, Shi XQ, Tronje G, Larsson A, Welander U, Frithiof L, Engstrom GN. The effect of hyaluronan on bone and soft tissue and immune response in wound healing. J Periodontol. 2001;72(9):1192–200. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.72.9.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]