Abstract

The Nigerian society is rapidly becoming urban as a result of a multitude of push and pull factors. This has generated urban health crises among city dwellers notably the urban poor. A systematic search of published literature in English was conducted between 1960 and 2015. Published peer review journals, abstracts, Gray literature (technical reports, government documents, reports, etc.), inaugural lectures, and internet articles were reviewed. Manual search of reference lists of selected articles were checked for further relevant studies. The review showed that the pace of urbanization is unprecedented with cities such as Lagos having annual urban growth rate of 5.8%. Urbanization in Nigeria is mainly demographically driven without commensurate socioeconomic dividends and benefits to the urban environment. This has created urban health crises of inadequate water safe supply, squalor and shanty settlements, sanitation, solid waste management, double burden of diseases and inefficient, congested, and risky transport system. In conclusion, when managed carefully, urbanization could reduce hardship and human suffering; on the other hand, it could also increase poverty and squalor. Some laws need to be amended to change the status of poor urban settlements. Urban health development requires intersectoral approach with political will and urban renewal program to make our urban societies sustainable that promote healthy living.

Keywords: Cities, Nigeria, urbanization, urban health, villes, Nigeria, urbanisation, santé urbaine

Résumé

La société nigériane devient rapidement urbaine à la suite d’une multitude de facteurs de push et pulls. Cela a généré des crises de santé urbaine parmi les citadins, notamment les citadins pauvres. La recherche systématique de la littérature publiée en anglais a été menée entre 1960 et 2015. Des revues d’examen par les pairs publiées, des résumés, la littérature grise (rapports techniques, documents gouvernementaux, rapports, etc.), des conférences inaugurales et des articles sur Internet ont été examinés. La recherche manuelle des listes de références des articles sélectionnés a été vérifiée pour d’autres études pertinentes. L’évaluation a montré que le rythme de l’urbanisation est sans précédent avec des villes comme Lagos ayant un taux annuel de croissance urbaine de 5,8%. L’urbanisation au Nigéria est principalement axée sur la démographie sans des dividendes et des bénéfices socio-économiques proportionnels à l’environnement urbain. Cela a créé des crises sanitaires urbaines d’approvisionnement inadéquat en eau, de squalers et de bidonvilles, d’assainissement, de gestion des déchets solides, de double charge de maladies et de systèmes de transport inefficaces, encombrés et risqués. En conclusion, lorsqu’ils sont bien gérés, l’urbanisation pourrait réduire les difficultés et les souffrances humaines; D’autre part, cela pourrait aussi augmenter la pauvreté et la misère. Certaines lois doivent être modifiées pour changer le statut des zones urbaines pauvres. Le développement de la santé urbaine nécessite une approche intersectorielle avec la volonté politique et le programme de renouvellement urbain pour rendre nos sociétés urbaines durables et promouvoir une vie saine.

INTRODUCTION

Today, there is no doubt that the world has increasingly become urban and the 20th century witnessed rapid and unprecedented urbanization of the world's population. The global urban population increased from 13% in 1900 to 29% in 1950, 49% in 2005 and it is estimated that by 2030, 60% of the population will live in the cities.[1] This trend is a reflection of the growth of urban population that increased from 220 million in 1900 to 732 million in 1950 and is expected that there will be 4.9 billion urban dwellers by 2030 (annual urban growth rate of 1.8%).[1] Almost all of this growth will be in lower income regions of Africa and Asia where urban population is likely to triple and in Asia will more than double.[2] Of all the regions of the world, Asia and Africa are urbanizing faster and are projected to become 56% and 64% urban, respectively by 2050. Three countries; Nigeria, India, and China combined are expected to account for 37% of the projected growth of the world population between 2014 and 2050. At the beginning of the 20th century, just 16 cities in the world (mostly in developing nations) contained a million people or more. Today, more than 400 cities have a population of a million or more, about 70% of them are found in developing countries. For the first time in history, in 2007, more people live in cities and towns than will be living in rural areas and by 2017, the developing nation is likely to have become more urban in character than rural.[2] While, there is no universal definition of what constitutes urban settlement, the criteria for classifying an area as urban may be based on one or a combination of characteristics as human population threshold, population density, proportion employed in nonagricultural sectors, presence of infrastructures such as paved roads, electricity, piped water or services, and presence of education and health services.[3] On the other hand, urbanization denotes a process whereby a society changes from a rural to urban way of life or redistribution of populations to urban settlements associated with development and civilization. For millennia, urban areas have been centers and drivers of commercial, scientific, political and cultural life, having a major influence on the whole countries and regions. The Nigerian society is undergoing both demographic transition (people are living longer) and epidemiological transition (change in population health due to changes in lifestyle) mainly as a result of urbanization. The country is undergoing rapid urbanization with a rapidly growing population. At current growth rate of about 2.8%–3% a year, Nigeria's urban population will double in the next two decades.

The pattern, trend, and characteristics of urbanization in Nigeria have been alarming. The towns and cities have grown phenomenally with pace of urbanization in Nigeria showing extraordinary high rates of 5%–10% per annum.[4] Consequently, there has been rapid expansion of Nigerian cities’ area up to 10-fold their initial point of growth[5] and the fact that the growth has been largely unplanned and uncontrolled.[6,7] Several studies have shown that inadequate planning of urban land uses in Nigeria and great intensity of use has exacerbated urban problems.[6,8]

In 1995, there were 7 cities with a population of over 1 million, 18 cities with over 500,000 population, 36 with over 200,000, and 78 with over 100,000. By 2020, it is projected that the number of cities with a population of 500,000 and 200,000, respectively will be 36 and 680 assuming annual urban growth rate of 5%.[9] Over the decades, the population of most major cities/towns has increased by many fold. Lagos, Kano, Port Harcourt, Maiduguri, Kaduna, Ilorin, and Jos all had more than 1000% increase over the past 5 decades. For instance, Kano's population rose from 5,810,470 in 1991 to 9,383,682 in 2006. Enugu had 174,000 in 1965, 464,514 in 1991, and 712,291 in 2006 while over the same period, Lagos had a population of less than a million, 4 million, and over 10 million, respectively.[10] Lagos is a mega city where inadequate infrastructure and services, housing shortage, traffic congestion, crime, street violence, and other social vices are well pronounced. These population increases account in part, for the rapid physical expansion of these cities and consequent creation of urban slums and urban villages. In 1950, only 10.1% of population was urban in Nigeria, this rose to 20.0% by 1970, 43.3% in 2000, and it is expected to reach 58.3% by 2020.[9]

Urbanization is a major public health challenge of the 21st century as urban populations are rapidly increasing, but basic infrastructures are insufficient and social and economic inequities in urban areas have resulted in significant health inequalities. In this sense, therefore, urbanization in a way is similar to globalization which can be seen as a structural social determinant of health that can challenge the aspirations of equity due to tendency of accumulation of wealth and power among urban elites. Today, most cities in Nigeria have undergone urban decay because of lack of or breakdown in basic services; potable water supply, electricity, efficient city transport services, affordable housing, and waste disposal systems. This is largely as a result of authorities coming to terms with the “tempo” of rising urban needs. These phenomenal transitions are not without health challenges to the population in urban areas and cities. These prompted this review as there is an obvious need to assess how these demographics can enhance our understanding of the current urban trait in Nigeria and its challenges. Urbanization is integrally connected to the three pillars of sustainable development, economic development, social development, and environmental protection,[1] and as urbanization proceeds in Nigeria, the pace and scale of urban population growth will generate important public health challenges for town planners and governments. This is more so since urbanization has not been associated with sustained industrialization and socioeconomic development across the country. Urban poverty and the growth of slums and shanty settlements which are critical challenges to urban health have grown remarkably. Thus, the “health for all will not be achieved for all Nigerians without re-orienting the system to deal with urban health problems.” Systematic search of published literature in English was conducted between 1960 and 2015. Published peer review journals, abstracts, Gray literature (technical reports, government documents, reports, etc.), inaugural lectures, and Internet articles were reviewed. Manual search of reference lists of selected articles was checked for further relevant studies. Here, we broadly review the current knowledge on trends of urbanization in Nigeria and health challenges posed by this phenomenon to provide an informed background to stimulate further research and to promote positive urbanization. In addition, health of Nigerians should be a major consideration in both urban renewal and future town planning to ensure that urbanization is not only friendly across all ages but also works to reduce the double burden of infectious and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs).

UNDERSTANDING URBANIZATION

Historically, cities have been the epicenter of economic development and centers of industry and commerce all over the world. If they are well managed, cities offer important opportunities, social and technological development, and facilitated the diffusion of information through interaction among diverse cultures. Cities have been focal points for political activities, systems of law, and good governments and employments. Cities have also been centers of scientific innovations, for instance in 19th century, urban residents in Europe were among the first people to widely practice family planning before the practice spread to countryside.[11]

The trend in urbanization and city growth in developing countries (including Nigeria) are caused by a multitude of factors – rural-urban migration, natural population increase and annexation, and expansion of neighborhoods. However, these factors are not mutually exclusive. It has been argued that because the rate of natural increase is lower in urban than rural areas, the main drivers of urbanization are rural-urban migration, expansion of urban areas through the process of annexation, and transformation of rural villages to small urban settlements. Thus, urbanization has outpaced industrialization. In Nigeria, urbanization has a long history in its growth and development. There were extensive urban developments that predate the British Colonial administration where cities have existed for centuries; Lagos, Ibadan, Kano, Sokoto, Calabar, and Port-Harcourt, etc. Lagos one of the world's largest cities, grew as a colonial Nigeria's capital and leading port. Till date, it remains the country's economic and cultural center. Ibadan was founded as a 19th century war camp, was the largest precolonial city in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) due to massive rural-urban migration. Its economy is based on agriculture and trade. Kano is the largest Hausa city in Northern Nigeria that became prominent as the center for a prosperous agricultural district (the ground pyramids) and as a major terminus of Trans-Sahara trade.[12] Today, it is a major commercial, industrial, transportation, and administrative center. Sokoto was the seat of the 19th century jihadist led by Usman Dan Fodio that spread Islamic religion to all the major cities in Northern Nigeria.[13] Other important cities include Oyo, Abeokuta, Ife, Zaria, Katsina, Jos, Bida, Calabar, and Enugu. Today, they are major centers for commercial, transportation, political, and industrial activities. Postindependence led to Africanization of public service and expansion of parastatal agencies resulting in a high rate of new employments in urban centers. Furthermore, the 1970s and 1980s saw acceleration in other sectors - banking, construction, and tourism. More recently is the impact of globalization and the free movement of peoples, goods, and services. Thus, postindependence migration into urban centers assumed deluge proportions.[14]

Table 1 shows urbanization growth experienced and that projected for some countries from SSA. Between 1970 and 1991, urban population growth rate ranged between 5.6% and 7.8%; Nigeria had the lowest urbanization rate of 5.4% while Kenya had the highest of 7.0%.[15]

Table 1.

Urbanization of low-income countries in Sub-Saharan Africa

| Urban population as a percentage of total population* | Urban population average annual growth rate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 1991 | 2000 | 1970-1980 | 1980-1990 | 1991-2000 | |

| Low-income countries | 28 | 39 (3127) | -(3686) | 3.7 | 5.0 | 2.4 |

| Kenya | 10 | 24 (25) | 32 (34) | 8.5 | 7.8 | 7.0 |

| Zimbabwe | 17 | 28 (10) | 35 (12) | 5.6 | 5.8 | 5.4 |

| Nigeria | 20 | 36 (99) | 43 (128) | 6.1 | 5.8 | 5.4 |

*Figures in parenthesis are estimates of total population in millions

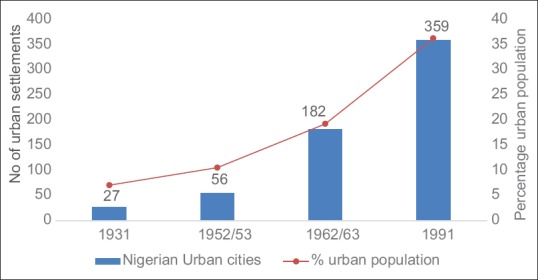

In Nigeria, there is disconnect between natural population growth rate and urban growth rate of over 5%. In addition, the perception that cities offer greater opportunities in terms of education, employments, research, and even search for marriage partners are powerful “pull” factors while population pressure on land resources has been seen as the main “push” factors for rural-urban migration in the southeast of Nigeria.[16] Other important factors that influenced urbanization in Nigeria includes creation of states in 1989 and 1991, creation of new local government areas (LGAs) with consequent establishment of more state capitals and LGA headquarters, as well as new universities and colleges in virtually every state, the building and subsequent relocation of the new federal capital to Abuja. Finally, population dynamics during the periods of enumeration for the two censuses (1991, 2006), thus, there could be the impact of these due to differential seasonal migration and movements of population within and across urban, rural, and across states and even the international borders. The urban population has been growing much more rapidly over the years as shown in Figure 1. Of all the regions in the country, the Southwest is the most urbanized with 40% of 329 urban centers in Nigeria.[16]

Figure 1.

Urbanization in Nigeria, 1931–1991

Between 1952 and 1991, urban population grew at annual average of 4.5%; by 1991, there were 359 towns compared to 56 and 182, respectively, in 1952/53 and 1963. Three cities of more than 1 million inhabitants (Lagos, Ibadan, and Kano) emerged and together accounted for about 10% of national population by 1991. As a result of these developments about one in three Nigerians (36%) lived in cities by 1991 compared to one in five in 1960. Lagos is reported to be the fastest growing city in Nigeria with annual growth rate of about 5.8% and population of 9,113,605.[17]

Finally, it must be recognized that Nigerian cities lack official recognition by the government, and no city in Nigeria is incorporated as such many of them are merged with rural areas in the same undifferentiated system of 774 local governments.[16] There is no or little concept of urban renewal or slum upgrading for the urban poor.[18]

MAIN FEATURES OF THE URBAN HEALTH CRISES IN NIGERIA

The environment

The issues of environment and urban health refer to the continued exposure to the risks of infectious diseases and injuries associated with poor sanitation, unsafe drinking water, heaps of solid waste, dangerous roads, polluted air, and toxic wastes, all of which are environmental health problems of poverty. Urban poverty is the most important predictor of the environmental health risks because in its broadest sense it also includes other forms of deprivation: physical assets, political influence, access to basic services, and access to social capital.[19] Before the turn of 21st century, poverty in Africa and indeed Nigeria was predominantly a rural phenomenon. It has many dimensions, which are part of the social reality of the poor in Nigeria, tends to be virtually re-enforcing, and trapping the poor in a vicious circle. The structural imbalances of the economy, bad governance, and an inappropriate development agenda and debt burden have been attributed to be major causes of poverty prevailing in Nigeria.[20] Nigeria had capital income of US$ 1000 in 1980; this dropped to US$ 310 by 1999 while the incidence of poverty increased from 27.2% of the population in 1980 to 65.6% in 1996, and now, it is estimated to be over 80%. Over the same period (1980 and 1996), the proportion of urban dwellers in poverty doubled, and the population of the urban core poor rose for 3% in 1980 to over 25% in 1996.[21] The country also had the highest income inequalities. Poverty and income inequality have a negative impact on the health seen as higher mortality risks, even after adjusting for individual characteristics such as income.[21,22] Therefore, deprivations must be addressed in all its forms as none of the other dimensions of deprivation can be tackled unless poverty and unemployments are solved.[23] Our cities have become highly vulnerable to environmental disasters. In the last 5–10 years, all the major cities in the country experience annual flooding as a consequence of torrential rainfall due to climate change.[24] The problem is worse, especially along the coastal cities. This has result in property loss and destruction worth billions of dollars.

Water supply

Access to safe water supply is a basic human need which must be satisfied with adequate quantities that comply with minimum health standards. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), almost 137 million people in urban populations across the world have no access to safe drinking water, and more than 600 million urban dwellers do not have adequate sanitation.[25] Despite the fact that Nigeria is blessed with abundant water resources, many urban areas including state capitals continue to face acute shortages of safe drinking water. There is a huge gap between demand and supply of safe, potable water as a result of urbanization because the majority of water agencies/boards cannot cope. Over the years, the argument has been that water supply was a social service, and subsidies were required to ensure access to water by the poor. However, in practice, this has led to a situation where lack of maintenance and underinvestment have deprived many poor households access to water and/or forced the poor to purchase water at exorbitant prices from water vendors. Subsidies have largely benefited those already better-off living in reserved areas of major cities in Nigeria.

In cities, quality of piped water cannot be guaranteed, tend to be highly turbid with sediment and access to piped water whether in the household or public taps is often highly irregular.[16] A report revealed that only 3% of residents of Ibadan have access to piped water, and in Lagos, only 9% of its 10 million residents have access.[26] However, recent NDHS report showed that there was no significant improvement in access among urban households (76%) between 2008 and 2013.[27] The most common source of improved drinking water is tube-well or borehole water used by 44% of urban residents. The situation varies among geopolitical zones and across the states. For instance in Lagos, street vendors are the single most important source of water, 37% of urban residents in Lagos households and another 3% by tankers,[16] respectively. This is against the Federal Government of Nigeria earlier policy that set urban water supply norms for Nigeria to provide 112 L/capita/day for all gazetted urban cities (20,000 persons and above) with pipe borne water supply.[28] All these are compounded by the fact that the main supplies often fail for days or even weeks due to multiple problems of erratic power supply, inadequate revenue generation, and weak sustainability; for many urban areas, the quality of the water is substandard that it presents potential health hazards. In general, owing to lack of foresight, planning without hard data, political and administrative interventions, and financial constraints, most urban water schemes designed for urban areas in Nigeria have become underdesigned as soon as they are commissioned.

Urban settlements

There are strong linkages between housing, water supply, and sanitation and health. Sound housing programs promote the satisfaction of these, other needs including privacy and security. Urban settlements that are inhabited by the urban poor are variously described as periurban, squatter, temporary, (or illegal settlements) and slums. By the year 2000, it was estimated that 60% of the world's population were living in such settlements.[13] Being illegal and unplanned, these settlements are located in parts of the city where health services and other social services such as schools, shopping centers are not accessible. The settlements do not officially exist and so are liable to evictions and demolition. Such demolition exercises have taken place in many cities (Abuja, Lagos, Kano, Zaria, and Port Harcourt) across Nigeria.

The Nigerian cities have huge housing deficits that started since the 1960s. The housing problem became worse because of inherent weaknesses of the past housing policies and programs. For instance, <15% of envisaged 202,000 housing units planned in 1975–80 period were actually completed and allocated. Again, the 200,000 new housing units earmarked to be built between 1980 and 85, only 19% were actually completed.[29] Between 1960 and 1970, total housing requirements in Nigeria were 2,380,000; this rose to 5,591,000 between 1970 and 1980. There is high occupancy ratio in these cities, with some like Lagos, Enugu, Onitsha, and Port Harcourt, having an average of 3 persons per room. By 2011, Nigeria housing deficit was estimated at between 12 and 16 million. According to Vision 2020 report, annual housing needs was put at ½–1 million housing units. The greatest problem facing housing in Nigeria is finance. It is estimated that more than 36 trillion naira will be required to meet the housing deficit (assuming a house will cost an average 3 million naira to build ($ 7500) (N 400 [Nigerian Naira] = $ 1). Despite the fact that Nigerian economy grew over a decade (2000–2011), it had no impact over housing delivery over the same period. Of recent are incessant episodes of collapsed dwelling structures in many urban areas across the country with loss of lives and properties. Consequently, many housing dwellings in our cities are not fit for human habitations. Underpinning all these is the fact that the country had numerous policies vis-à-vis National Housing Policy of 1980, National Urban Development Policy of 1997, and the National Housing and Urban Development Policy of 2002 specifically to meet quantitative demand on housing needs of Nigerians through mortgage finance. During the period, the ongoing housing reforms led to the creation of Federal Ministry of Housing and Urban Development from Works and Housing in 2003.[30] All these policies suffer from planning inconsistency and weak organizational structures due to political instability and implementation.[31] Thus, a recent study by UCLG and Cities Alliance reported on Nigeria that though national reflection on urbanization is underway, there is no defined national urban strategy. It further reported that currently, Nigeria is not among countries in Africa with a clear National Urban Strategy along with financial and technical capacities to implement it.[32]

Sanitation in urban areas

While access to toilet facilities has been constantly higher in urban areas than rural, available data reveal improvement over the years have not been dramatic. According to the NDHS report, the proportion of households using improved, not shared toilet facilities in urban areas is 42.7%.[27] This implies that many urbanites still exhibit their rural habits as large number of people urinate and defecate in open spaces with serious health implications in densely populated urban settlements. There is no single city in Nigeria with a modern central sewerage system.[33] A study in four major cities of Lagos, Ibadan, Kano, and Onitsha reported that the proportion of households connected with sewage systems was very low and varied from none at all in Ibadan and Onitsha to 2%–3% in Lagos and Kano while <1% of waste water is these cities were treated.[16] Hence, as urbanization proceeds and urban population continued to grow rapidly, sanitation worsened. The provision of sanitation in Ibadan, Nigeria's largest city is grossly deficient as in most cities in SSA.[34] There is lack of effective system of refuse collection. Unorganized, haphazard disposal of wastes takes place at the fringes of squatter and slum areas even in metropolitan Lagos. Disposal of refuse is inefficiently organized in virtually all urban areas. Mabogunje reported that uncollected solid wastes also prevent adequate water drainage and contribute to water pollution.[35] Solid waste management has emerged as one of the greatest challenges facing states and local government Environmental Protection or Management Agencies in Nigeria. Thus, the municipal administrations have without exception failed woefully in managing the disposal of solid waste now being generated at ever-increasing rates due to lack of fund.[36]

In Nigeria, over 25 million tonnes of municipal solid waste are generated annually; Table 2 shows the waste generation rates and breakdown density.[37] In the study of nine cities in Nigeria, wastes are commonly dumped in open dumps, uncontrolled landfills, and dumps located along or beside major roads. In many cities, refuse spreads into the roads, blocking traffic, and wastes are often burnt in the open on the side of the road, thereby posing potential hazards of air pollution and fire accidents. The dangers of open dumping and burning, health hazards to scavengers, injuries and cuts, pollution of ground water, spread of infectious diseases, emission of toxic fumes or smoke from smoldering fires, and foul odor from decomposing refuse. Incineration method of waste disposal where practised is of small scale often restricted to health facilities for disposal of medical wastes, and waste-to-energy technology is not practised presently in Nigeria [Table 3].[38]

Table 2.

Urban solid waste generation in Nigeria

| City | Population | Agencies | Ton/month | Density (kg/m2) | Kg/capita/day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagos | 8,029,200 | Lagos Waste Management Agency | 255,556 | 294 | 0.63 |

| Kano | 3,248,700 | Kano Environmental Protection Agency | 156,676 | 290 | 0.56 |

| Ibadan | 307,840 | Oyo State Environmental Protection Comm | 135,391 | 330 | 0.51 |

| Kaduna | 1,458,900 | Kaduna State Environmental Protection Agency | 114,433 | 320 | 0.58 |

| Port Harcourt | 1,053,900 | River State Environmental Protection Agency | 117,825 | 300 | 0.60 |

| Makurdi | 249,000 | Urban Development Board | 24,242 | 240 | 0.48 |

| Onitsha | 509,500 | Anambra State Environmental Protection Agency | 84,137 | 310 | 0.53 |

| Nsukka | 100,700 | Anambra State Environmental Protection Agency | 12,000 | 370 | 0.44 |

| Abuja | 159,900 | Abuja Environmental Protection Agency | 14,785 | 280 | 0.66 |

Table 3.

Nature of solid waste depots or dumps in 15 Nigerian cities

| Type of depots/dumps | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Ground surface | 71.0 |

| Metal/plastic container | 17.8 |

| Walled structure | 4.0 |

| Pit | 6.4 |

| Others | 0.8 |

| Total | 100.0 |

In Nigeria, very few if any urban areas have public conveniences (lavatories) even in public places (markets, mosques and churches) that are well maintained and functional. Nowadays, it is not unusual to find privately operated public conveniences in the parks (charging between 0.05 and 0.25 US$ per use). There is thus urgent need for shared responsibilities among all the tiers of government backed by adequate budgetary allocations to avert impending urban environmental sanitation crises in our cities.

Urban transport system

More than 95% of urban transports in Nigeria is by road, and about 70% of these trips are by public transport.[39] Road traffic injuries are development and social issues with public health consequences. Transport systems in our cities are grossly inadequate, inefficient, risky, and unreliable. One of the major consequences of this is that people have to wait and or walk long distances to work and many often use congested and expensive transports. The problem occurs due to lack of adequate transport that grows in proportion with urbanization. The rate of vehicle growth is much lower than population growth rate. Indeed, it has been reported that Nigeria has the lowest level of motorization in West Africa at four vehicles per 1000 inhabitants.[40] After the structural adjustment program of the 1980s, the economy improved and the consequences of that were increased car ownership to circumvent the chaotic transport system. In many Nigerian cities, car ownership became a “basic” necessity as public transportation is a nuisance, uncomfortable, and unreliable. Even though urban transportation is to facilitate the movement of goods and people comfortably and safely, what exists in Nigerian cities are a litany of inconvenience and frustrations.[41,42] The urban transport system which serves as a sinew, binding together various land uses has not only remained inefficient but has grown over the years to be expensive and dangerous.[4] This is because only about 30% of all categories of roads in Nigeria could be regarded as being in good condition while the remaining 70% are in various stages of disrepair.[40] In addition, in the last two decades, the influx of motorcyclists and motorized two-wheelers has compounded the traffic mix of the cities. The country as a whole has a low helmet usage rate at <5%.[43]

Air pollution

Atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases; carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide are increasing due to human activities such as fossil fuel combustion, land use changes, and agriculture. The atmosphere is a natural laboratory, in which various gases, solid particles, and sunlight are involved in different chemical processes. The natural by-products of these processes are being profoundly altered by anthropogenic activities, especially in the urban areas.

Before 1970s when urbanization and industrialization were at low levels in Nigeria, most cities in the country would have passed any safety standards with respect to air pollution. However, the oil boom of the mid 1970s and rapid industrialization that followed to the present gradually made the problem of air pollution a fact to be reckoned with in the country, particularly in the industrialized cities. For example, the air over Lagos where the 38% of the manufacturing industries in the country are located is credited with characteristic unpleasant odor with its skyline not becoming visible until around midday due to grayish industrial haze.[29] The effects of these chemical by-products can lead to economic effects from damage to materials, vegetations, and livestock. Human beings face the hazards of fumes emitted from vehicles, especially in urban centers with heavy road traffics, when air is stagnant exhaust gases from cars and generators will accumulate, leading to eye irritation, plant damage, and even fatalities. In large cities like Lagos, which suffer perennially from traffic congestion with peak hour operating speeds of <10 km/h, there is high-emission rate of carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide from automobile exhaust. Values far >0.02 part per million limits recommended by the WHO have been reported for many cities in Nigeria. Several studies[44,45] from Nigeria have shown that the air in Nigerian environment is far from clean. Sources of pollution are dust particles and vehicular traffic. Emission rates of dust per vehicle-kilometer for paved and unpaved roads in all parts of Nigeria are higher when compared to 0.1 g per vehicle-kilometer for roads in London. The annual amount of dust kicked up in the air by motor vehicles in Nigeria was more than 612,000 and 187,000 tonnes for unpaved and paved roads, respectively.[29] In addition, more than 584,000 tonnes of smoke particles were estimated to be emitted into atmosphere for burning about 80 million m3 of fuelwood. The economic situation in Nigeria (1986–2008) has led to increased importation of used (Tokunbo) vehicles into the country. These used vehicles with outdated and battered engines emit obnoxious gases at levels higher than permitted.[36] Finally; up till now, Nigeria is among a few if not the only country in world where gas flaring with its disastrous consequences is still taking place. The gaseous emissions from flare mix with humid air to produce weak dilute solution termed acid rain with its effects on vegetations, clothing, and houses.

Indoor air pollution can be traced to prehistoric times when man used fire for cooking and keeping warm. Today, urban residents rely heavily on unprocessed biomass fuels (wood, crop residues, animal dung, and coal) because of unavailability and cost of refined fuels (cooking gas, kerosene, and electricity). These fuels burn (uncleanly) indoors with high levels of air pollution thereby exposing the inhabitants of the dwellings, especially children and women to health hazards. Underpinning all these is poverty which has become a major barrier to use of cleaner fuels in urban areas. Many substances in biomass can damage human health and include particles, carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide, formaldehyde, and polycyclic organic matter.[46] It is reported that particles with diameter <10 μ (PM10) and those <2.5 (PM2.5) can penetrate lung tissues and have the potential to damage human health.[47]

Urban agriculture

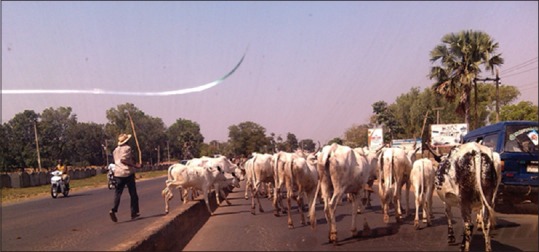

Urban agriculture is not a new adventure in the country and has been associated with history of urbanization in Nigeria. The famous ground nut pyramids in Kano, Cocoa production in Ibadan, Oyo, Ife, and Cassava plantation in Benin all pre-dated British colonialism. The booming petrodollars of the 1970s coupled with the creation of states and resultant demand for civil jobs led to subsequent abandonment of agriculture. Thus, in urban areas, malnutrition, undernutrition, and increases in food prices have placed access to nutritious food high in the list of health concerns for the urban poor dwellers.[48] Despite its potential benefits, urban agriculture has not been part of urban planning in Nigeria. However, in recent times, agriculture and animal husbandry are increasing in cities and approximately up to 50% of families carry out some type of small-scale gardening for food despite both official disapproval and regulatory prohibition. This practice reflects both cultural and economic forces, a form of insurance against monetary poverty, especially for the urban deprived. Urban agriculture has nutritional, economic and social benefits but with increased health hazards. It can potentiate vector-borne infectious diseases (development of mosquito breeding sites in irrigation channels) and use of pesticides. Livestock often is herded through central business districts and is a common sight in residential, commercial, and market areas. They constitute a constant nuisance on major roads (both intra- and inter-city highways) causing traffic congestions and also a source of accidents, Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Livestocks and vehicles competing for the right of way on a major urban road

If planned properly, urban agriculture has cumulative effects; meeting some basic nutrition needs of urban residents, an opportunity to alleviate urban poverty, aid government's initiatives to get people back to work (not necessarily white collar jobs), and put the country back on food sufficiency. On the health side, it has been reported that gardening is a viable form of exercise that can reduce the risk of coronary heart disease in both sexes,[48,49] reduce obesity, and diabetes as well as improve glycemic control in adults and elderly men.[50] The WHO's healthy cities program has recognized the benefits of urban agriculture and appealed to cities and their governments to incorporate food policies into urban planning.[51] This is an opportunity for the Federal Government to incorporate urban agriculture in all its future urban development plans. However, as cities expand the resulting growth forces agricultural activities to previously forested areas leading to erosion and desertification.

Urban health services

Under the Nigerian constitution, health is on the concurrent legislative list of Federal, state, and local government responsibilities, and the health system that is based on the Primary Health Care (PHC). All the three tiers of government are involved in health service delivery. These services are not equitably accessible even within the urban areas. In general, health services in Africa are grossly underfunded, in 2001 African leaders made Abuja declaration with a commitment to allocate at least 15% of public expenditure to health by 2015.[52] However, health spending is still nowhere near where it needs to be as there are still huge funding gaps. Urbanization has contributed to overall improvement of health and to a major shift in patterns toward a rise in chronic diseases. Even with urban “advantage” (health benefits of living in urban as opposed to rural areas), the rich and poor people live in a very different epidemiological environments even within the same city. Consequently, important socioeconomic disparities have emerged in urban areas mirrored by profound health inequalities.[2,53] Furthermore, health is determined by many factors outside the biomedical domain,[48,54] and as urbanization continues in the context of poor economic performance and poor governance, a rapidly increasing population of urban dwellers are living below the poverty line in overcrowded slums and shanty towns. On average, about 78% of Nigerians live within 10 km of some kind of health facility even though there are regional variations, with those in Southwest being 88% compared to 67% in the northwest. In general, health indices in urban areas are much better than in rural areas, but the current trends in urbanization are blurring this urban advantage as a result of health of slum dwellers. Women in urban areas are more likely to receive antenatal care than those in rural areas, and 52% of urban women are likely to make use of health-care facility.[20] In terms of reproductive performance, there are large rural-urban differences in age-specific fertility rates for all age groups [Figure 3][27] and total fertility rate (TFR - average total number of children a woman will have after completing her reproductive cycle) also revealed this differences, 6.2 versus 4.7.

Figure 3.

Trends in age-specific fertility rates by rural-urban residence

The urbanized geo-political zones in Nigeria had a low TFR of 4.3 (South–South), 4.6 (south-west), and 4.7 (south-east) respectively. Even though there are wide zonal differences, the national average TFR is 5.5 children per woman. Against this background, the urban poor dwellers have a higher TFR that is comparable with rural folk. They also lack access to health facilities and thus deliver at home.

Diseases

Urbanism potentiates many changes in human behavior that affects disease risks, and the deterioration in the built environment is sharply in evidence throughout most of the urban areas in Africa. Urbanism increases mobility and relaxation of traditional cultural norms yield new patterns of human behavior including changes in sexual activities and the use of illicit drugs.[55] Psychoactive substances such as alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and heroin have been available for use for many years now. The problems related to psychoactive substance are well known and have devastating effects on the health of the individual and society. Its use in urban areas is diverse: commercial sex workers, unemployed youth, commercial motorcyclists, and drivers. In a study from South-South Nigeria, more than 90% of intracity drivers reported consuming alcohol for pleasure.[56] A similar pattern of use was reported among commercial drivers in Kaduna metropolis.[57] Alti-Muazu and Aliyu reported the use of marijuana (25.8%) and solution (24.5%), respectively, among commercial motorcyclists in Zaria city, North West Nigeria.[58] Drug abuse and illicit substance use are also associated with urban violence and crime that are often related to stresses of poverty in our cities.

In addition, the rise in NCDs is strongly associated with urbanization and is driven by enormous social and economic changes that are compounded by globalization. The heterogeneity in health of urban dwellers increased mobility and rates of contact results in a high risk of disease transmission in large urban populations.[2] Thus, our cities have become incubators where all disease conditions are made favorable for outbreaks to occur. Urban growth might be driven by different forces in different cities and the epidemiology of individual diseases might differ according to specific urban dynamics and contexts.[26] Thus, the extensive transmission of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s is a combination of the new sexual freedom, movement between urban and rural areas, illicit drug use, and long distance travels. Urbanization is expanding the role of cities as gateways for infections. The outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Lagos city, Nigeria on 20th July 2014 is a good example. Lagos, the largest city in Africa, is a regional economic hub, industrial and travel activities with air, land, and sea ports of entry.[59] The index case (an acutely ill traveler) arrived from Liberia at international airport in Lagos; the disease later spread to other cities in Nigeria.

In SSA, hospitals and clinics regularly report >15% of admissions are due to malaria. Even though some cases are referrals from rural areas, malaria transmission in urban (urban malaria) and periurban settings is a significant problem.[60] It is thought that about 10 species of anopheles are responsible for malaria transmission in SSA, but for urban malaria, there are three: Anopheles gambiae, Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles funestus. The urban environments may provide potentials for malaria transmission in a number of ways: for many urban residents, frequent travel to rural areas on a regular basis is a predictable activity that exposes the vulnerable individuals to mosquito bites. Many urban areas have vegetations coupled with urban farming that provides ample aquatic habitats for mosquitoes. Added to this, the physical deteriorating environment (blocked and broken drainages, heaps of refuse, etc.), new constructions (excavations, building constructions, and irrigation schemes) and population dynamics may increase opportunities for mosquitoes through the enhancement of shallow bodies of water and increase in number of artificial water collection reservoir. Studies have reported that anopheles species seems to be adapting to urban ecosystems and Chinery[61] reported that A. gambiae species has adapted to urban aquatic habitats (water-filled domestic containers and polluted water habitats) in Accra, Ghana as a result of urbanization. In another study, it was reported that A. gambiae showed a strong preference for man-made, temporary aquatic sites.[62] Consequently, with all these factors, as more people move into cities and industrialization proceeds, urban malaria is on the increase in Nigeria.[63,64] Thus, the survival of A. gambiae species is widespread in polluted water across Lagos metropolis could be responsible for the rise on the incidence of malaria in urban Lagos and could indicate that the mosquito has adapted to a wide range of water pollution in urban settings that could have serious implications on the epidemiology of urban malaria.

The rapid urban growth and its unsanitary environment could favor the proliferation of disease vectors and transmission of the neglected tropical diseases such as soil-transmitted helminthiasis, schistosomiasis, and lymphatic filariaisis.[65,66] Lymphatic filariasis (LF) is a disabling and disfiguring disease that results from a mosquito-borne parasitic infection. Among 30 suspected cases of clinical LF, 18 had lived in Jos for more than 5 years and among 98 compliment fixation agglutination tested individuals, 6 were positive and lived in Jos.[67] In a study from Ijebu-Ode, Ogun state, the prevalences of Ascaris lumbricoides, hookworms, Taenia spp, Schistosoma mansoni, and Strongyloides stercoralis in urban center were similar to those in the rural communities.[68] Finally, Lassa fever was first described in 1950 in Sierra Leone, but the virus that caused the disease was not identified until 1969 when 2 missionary nurses died in Lassa town (hence the name of the disease) in North East, Nigeria. Since then, a number of outbreaks of Lassa virus infection were reported in various parts of Nigeria including Jos, Onitsha, Zonkwa, Owerri, Ekpoma, and Lafiya.[69]

CONCLUSION

The review has shown that managing urban growth and urbanization in Nigeria have become one of the most important challenges of the 21st century. Urbanization has been seen as potential driver of economic development, industrialization, human welfare, and structural transformation as it makes cities become engine of growth and sustainable development. Hence, if managed carefully, urbanization could help to reduce hardship and human suffering; on the other hand, it could also increase urban poverty and squalor. As the nation grabbles with urbanization and urban health crises, two potential issues need to be addressed urgently. First, the law has to be amended to deillegalize the settlements of urban poor. These settlements have to be recognized as permanent features of urban life. This way, the settlements can have a legal status and be part of all future urban development planning. The urban poor is a problem of the nation and not that of urban authorities. Second, the Federal Government need to source for funds to channel to urban authorities nationwide for proper urban planning and development. Because of the nature of dominant health problems associated with rapid urbanization, these health problems can be addressed through the nine basic components of PHC (i.e. health education, food supply and proper nutrition, safe water supply and basic sanitation, maternal and child health, immunization, prevention of endemic diseases, treatment of common diseases and injuries, and provision of essential drugs). Finally, improved health outcomes will need a concerted effort to create and maintain the so-called urban advantage through reshaping of city environment. There is urgent need for institutional and legal frameworks to reinvigorate urban renewal. This will require intersectoral approach through the building of political alliance for urban health that involves stakeholders, urban planners, health officials, and practitioners.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Washington DC, New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2015. United Nations: World Population Prospects: The 2014 Revision United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alirol E, Getaz L, Stoll B, Chappuis F, Loutan L. Urbanisation and infectious diseases in a globalised world. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:131–41. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70223-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen B. Urbanization in developing countries: Current trends, future projections and key challenges for sustainability. Technol Soc. 2006;28:63–80. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egunjobi L. Our Gasping Cities; an Inaugural Lecture. University of Ibadan; 21st October. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agbola T, Agbola EO. The development of urban and regional planning legislation and their impact on the morphology of Nigerian cities. Niger J Econ Soc Stud 1997. 39(1):123–44. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egunjobi L. Onakomaiya SO, Oyesiko OO, editors. Planning of the Nigerian cities for better quality of life. Environment, Physical Planning and Development in Nigeria. 2002:89–107. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olarenwaju DO. Inaugural Lectures, Akure: Federal University of Technology; 26th October; 2004. Town Playing. A Veritable Means for Poverty Reduction. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Washington DC, USA: 2006. Foundation for Urban Development in Africa. The Legacy of Akin Mabogunje; The Cities Alliance. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onibokun A, Faniran A. Urbanization and Urban Problems in Nigeria. Urban Research in Nigeria. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 10]. Available from: http://www.books.openedition.org/ifra .

- 10.National Population Commission/National Bureau of Statistics 2008. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 26]. Available from: www.nigeriastat.gov.ng/nada/index .

- 11.Brockerhoff BP. An Urbanizing World. Popul Bull. 2000;55:3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The People of Nigeria: Urbanization. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 10]. Available from: http://www.nigeria/htm .

- 13.Fodio SU. Handbook on Islam Ihsan. Great Britain: The Chaucer Press Ltd; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNDP, Oxford University Press; 1993. United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang’ombe JK. Public health crises of cities in developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:857–62. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00155-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNICEF. Children's and Women's Right in Nigeria: A Wake up Call: Situation Assessment and Analysis. 2001:11–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abuja: National Population Commission; 1998. National Population Commission (NPC). 1991. Population Census of the Federal Report of Nigeria: Analytical Report at the National level. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mabogonje AL. Cities for All: The Challenges for Nigeria. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Works and Housing; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. The World Health Report. Bridging the Gaps. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sofo CA, Akpajiak A, Pyke T. Measuring Poverty in Nigeria. Oxfam, UK: Oxfam Working Papers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alma Ata: Primary Health Care in Nigeria; 2008. Health Reform Foundation of Nigeria (HERFON). Nigerian Health Review 2007. 30 Years After. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lochner K, Pamuk E, Makuc D, Kennedy BP, Kawachi I. State-level income inequality and individual mortality risk: A prospective, multilevel study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:385–91. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geneva: United Nations Press Release; 1993. United Nations. SG/SM/1457, ECOSOC/1409. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aliyu A. Management of disasters and complex emergencies in Africa: The challenges and constraints. Ann Afr Med. 2015;14:123–31. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.149894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO, UNICEF. Progressing on Drinking Water and Sanitation: Special Focus on Sanitation. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 15]. Available from: http://wwwwho.int/water/sanitation_health/monitoring/jmp2008.pdf .

- 26.Satterthwaite D. The Transition to a Predominantly Urban World and its Underpinning. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 15]. Available from: http://www.iied.org/publications/pdf/10550IIED .

- 27.Abuja, Nigeria and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICFI; 2014. National Population Commission (NPC) and ICF International. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: United Printers; 1981. First Things First: Meeting the Basic Needs of the People of Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nigeria's Threatened Environment. A National Profile – Nigeria Environmental Study Action Team (NEST). Not dated [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiboye AD. Urbanization challenges and housing delivery in Nigeria: The need for an effective policy framework for sustainable development. Int Rev Soc Sci Humanit. 2011;1:76–185. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiboye A. A critique of official housing policy in Nigeria. In: Amole B, editor. The House in Nigeria, Proceedings of National Symposium. Nigeria: Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife; 1997. pp. 284–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.UCLG. (United Cities and Local Governments of Africa) and Cities Alliance. Assessing the Institutional Environment of Local Governments in Africa, Morocco. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 15]. Available from: http://www.localafrica.org .

- 33.Enweze C. Proceedings of the 20 Governors Seminars and Donors Conference on Strategies of Attracting Investment in Water Supply and Sanitation Sector. Abuja, Nigeria: 2000. African development bank experience and strategy in the water supply and sanitation sector in Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oloruntoba EO, Folarin TB, Ayede AI. Hygiene and sanitation risk factors of diarrhoeal disease among under-five children in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14:1001–11. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v14i4.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mabogunje AL. Poverty and Environmental degradation: Challenges within the global economy. Environment. 2002;44:8–18. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Don-Pedro KN. Man and the Environmental Crisis. Nigeria: University of Lagos Press; 2009. Solid and hazardous wastes Management. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogwueleka T. Municipal solid waste characteristics and management in Nigeria. Iran J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2009;6:173–80. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Federal Ministry of Housing and Environment. The State of the Environment in Nigeria. Monograph Series No. 2. Lagos- Nigeria [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asiyanbola RA. Urbanization, gender and transport research issues and insights in Nigeria; Towards a sustainable gender sensitive transport development. Niger J Soc Anthropol. 2010;8:30–44. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Filani MO. Onakomaiya SO, Oyesiko OO, editors. Mobility crises and the federal government mass transit programme. Environment, Physical Planning and Development in Nigeria. 2002:37–51. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nwagah O, Semeniteri I, Ugoani A, Ubanna S, Oyewale D, Ariole A. Infrastructure: A rotten foundation. Tell Magazine. 2003;23:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ayodeji O. Ibadan: IFRA Occasional Publication; 2003. Infrastructure Development and Urban facilities in Lagos, 1861-2000; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brazzaville: WHO Regional Office for Africa; 2010. World Health Organization (WHO). Status Report on Road Safety in Countries of WHO African Region. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akeredolu F. Atmospheric environment problems in Nigeria: An overview. Atmos Environ. 1989:783–92. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Isichei AD, Akeredolu F. Acidification potential in the Nigerian Environment. In: Rhode H, Herrerd R, editors. Acidification in Tropical Countries. New York: SCOPE/Wiley; 1988. pp. 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bruce N, Perez-Padilla R, Albalak R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: A major environmental and public health challenge. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1078–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.United States Environmental Protection Agency. Revisions to the national ambient air quality for particles matter. 1997;62:38651–701. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rydin Y, Bleahu A, Davies M, Dávila JD, Friel S, De Grandis G, et al. Shaping cities for health: Complexity and the planning of urban environments in the 21st century. Lancet. 2012;379:2079–108. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60435-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reynolds LR, Anderson JW. Practical office strategies for weight management of the obese diabetic individual. Endocr Pract. 2004;10:153–9. doi: 10.4158/EP.10.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wood DM, Brennan AL, Philips BJ, Baker EH. Effect of hyperglycaemia on glucose concentration of human nasal secretions. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;106:527–33. doi: 10.1042/CS20030333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morgan K. Feeding the city: The challenge of Urban food planning. Int Plan Stud. 2010;14:341–8. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abuja declaration, Africa. Africa Health. 2013;35:9. [Google Scholar]

- 53.UN Habitat. State of World Cities. 2006/2007. [Last accessed on 2015 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www/unhabitat.org/ponss/listItem .

- 54.Sclar ED, Garau P, Carolini G. The 21st century health challenge of slums and cities. Lancet. 2005;365:901–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McMichael AJ. The urban environment and health in a world of increasing globalization: Issues for developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1117–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bello S, Fatiregun A, Ndifon WO, Oyo-Ita A, Ikpeme B. Social determinants of alcohol use among drivers in Calabar. Niger Med J. 2011;52:244–9. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.93797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okpataku CI. Pattern and reasons for substance use among long-distance commercial drivers in a Nigerian city. Indian J Public Health. 2015;59:259–63. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.169649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alti-Muazu M, Aliyu AA. Prevalence of psychoactive substance use among commercial motorcyclists and its health and social consequences in Zaria, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2008;7:67–71. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.55678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shuaib F, Gunnala R, Musa EO, Mahoney FJ, Oguntimehin O, Nguku PM, et al. Ebola virus disease outbreak- Nigeria. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:867–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robert V, Macintyre K, Keating J, Trape JF, Duchemin JB, Warren M, et al. Malaria transmission in urban sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:169–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chinery WA. Variation in frequency in breeding of Anopheles gambiae s.l. and its relationship with in-door adult mosquito density in various localities in Accra, Ghana. East Afr Med J. 1990;67:328–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khaemba BM, Mutani A, Bett MK. Studies of anopheline mosquitoes transmitting malaria in a newly developed highland urban area: a case study of Moi University and its environs. East Afr Med J. 1994;71:159–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Awolola TS, Oduola AO, Obansa JB, Chukwurar NJ, Unyimadu JP. Anopheles gambiae s.s. breeding in polluted water bodies in urban Lagos, Southwestern Nigeria. J Vector Borne Dis. 2007;44:241–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brieger WR, Sesay HR, Adesina H, Mosanya ME, Ogunlade PB, Ayodele JO, et al. Urban malaria treatment behaviour in the context of low levels of malaria transmission in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2001;30(Suppl):7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simonsen PE, Mwakitalu ME. Urban lymphatic filariasis. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:35–44. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-3226-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Utzinger J, Keiser J. Urbanization and tropical health – then and now. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100:517–33. doi: 10.1179/136485906X97372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Terranella A, Eigiege A, Gontor I, Dagwa P, Damishi S, Miri E, et al. Urban lymphatic filariasis in central Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100:163–72. doi: 10.1179/136485906X86266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Agbolade OM, Agu NC, Adesanya OO, Odejayi AO, Adigun AA, Adesanlu EB, et al. Intestinal helminthiases and schistosomiasis among school children in an urban center and some rural communities in Southwest Nigeria. Korean J Parasitol. 2007;45:233–8. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2007.45.3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ogbu O, Ajuluchukwu E, Uneke CJ. Lassa fever in West African sub-region: An overview. J Vector Borne Dis. 2007;44:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]